Key Points

Question

What are the clinical differences observed in cases of posterior uveal melanoma in patients younger than 21 years compared with older patients?

Findings

This case series showed that the clinical features of the intraocular tumors are not considerably different than those of other age groups, and it confirmed the rarity of uveal melanoma among patients younger than 21 years. However, these findings indicate that patients younger than 21 years have a relatively high frequency of metastasis and melanoma-associated death.

Meaning

Posterior uveal melanoma in patients younger than 21 years appears to have similar if not worse prognosis than the same disease in the patient population overall.

This cohort study analyzes clinical records from 1980 to 2013 to identify rates of metastasis and survival in patients younger than 21 years with posterior uveal melanoma.

Abstract

Importance

Given the rarity of posterior uveal melanoma in patients younger than 21 years, reporting clinical experience in this area has relevance.

Objective

To describe the baseline clinical features, treatment, and clinical course of a group of patients younger than 21 years who have primary posterior uveal melanoma.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective descriptive case series of patients younger than 21 years who have a primary choroidal or ciliochoroidal melanoma was conducted at a single-center subspecialty referral practice. Patients in the relevant age group who were treated in a single practice between July 1980 and December 2013 were included; clinical data collected through December 2017 were captured to permit adequate follow-up time in all cases.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Conventional descriptive statistics of relevant clinical variables (eg, demographic, tumor, treatment, and outcome variables) of each patient were recorded. Actuarial metastasis-free and overall survival curves were computed and plotted, as was a postdetection survival curve of patients who developed metastasis during available follow-up.

Results

Of 2265 patients with posterior uveal melanoma encountered by the authors during the study interval, 18 (0.8%) were younger than 21 years when diagnosed and treated. Ten were female and 8 male, and the mean (SD) age was 16.6 (4.2) years. Through available follow-up, 8 of these patients had developed metastatic uveal melanoma (44%). All 8 died of metastasis. Actuarial survival analysis showed that the cumulative probability of metastatic death in this group exceeded 50%. The median overall survival time after treatment of the primary intraocular tumor was 11.9 (95% CI, 7.3-16.5) years. The median survival time after detection of metastasis in the 8 patients who developed metastasis was 2.3 months (95% CI, 0.0-5.2) months.

Conclusions and Relevance

Posterior uveal melanoma in patients younger than 21 years appears to have a similar if not worse prognosis than patients with PUM in the population overall. Owing to the later onset of metastasis observed, patients younger than 21 years should continue to have surveillance tests for more than 10 years after treatment.

Introduction

Primary posterior uveal melanoma (PUM) is a malignant intraocular neoplasm that affects mostly older adults. The mean age at detection of the intraocular tumor in most large series is between 60 and 62 years.1 The mean annual incidence of this malignant intraocular neoplasm among people of white ancestry (the group most likely to develop the disease) across all age groups has been estimated to be between 5 and 8 new cases per million persons per year,2,3 but fewer than 1 new case per million persons per year is generally encountered in individuals younger than 30 years.4,5 The percentage of primary PUM cases diagnosed in persons younger than 21 years has been estimated to be approximately 1%.5,6,7,8 Because of the rarity of such tumors in young persons, few clinicians encounter more than a few such cases over an extended career. Recognizing this infrequency, a retrospective analysis of our clinical experience would be appropriate to provide information about this subgroup of patients with PUM and features associated with this early presentation.

The purpose of this study is to describe a cohort of patients younger than 21 years who had a PUM and were evaluated and managed in a single practice over a 33.5-year interval. Tumor clinical features, treatments, and metastatic and survival outcomes are included.

Methods

This is a retrospective descriptive analysis of a defined cohort of patients with primary posterior uveal melanoma. This study received an institutional review board waiver because it uses retrospective deidentified data collected in the University of Cincinnati Ocular Tumors Database. All patient information was kept confidential and used in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. This research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The starting patient group for this study consisted of all patients diagnosed with PUM encountered by 2 of the authors (J.J.A. and Z.M.C.) in their clinical practice between July 1, 1980, and December 31, 2013. The records of all patients in this group who were younger than 21 years at the time of diagnosis and initial treatment were selected for further analysis, including all data from the start of treatment through December 2017 (to permit adequate follow-up time for the most recent patients). The age cutoff for this report was set at 21 years, given that similar studies examining PUM in pediatric patients have historically defined this patient population as younger than 21 years.4,5,6 All of the patients underwent a comprehensive diagnostic ophthalmic physical examination with fundus mapping, photographic documentation of fundus features, and ocular B-scan ultrasonography. Patients and/or their parents or guardians were informed in detail about the clinical diagnosis, expectations for the ophthalmic and systemic prognoses of the patients if untreated, and the recognized potential benefits vs potential risks and limitations of clinical management options (including no treatment) for the diagnosed tumor that were available at that time.9 Patients who underwent enucleation or transscleral en bloc resection of the intraocular tumor had their tumor tissue submitted to pathology for histopathological analysis and melanoma cell-type classification.

Relevant baseline clinical variables (demographic variables, general ocular status variables, and intraocular tumor variables)10,11,12; predisposing factors, such as oculodermal melanocytosis and family history of uveal melanoma or other cancers suggestive of BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome; initial treatment and when it occurred; histopathological cell type of the tumor, if available; information on whether and when metastasis was detected during available follow-up; and information on whether, when, and why the patient died during available follow-up were abstracted from the patients’ ophthalmologic medical records and from external records provided by the patients’ oncologists. All metastases were confirmed either by biopsy or appropriate imaging of the affected organ or organs.

Statistical analysis consisted of conventional descriptive statistics computed for the patients in the group, and actuarial (Kaplan-Meier) curves of metastasis, metastatic death, and death from any cause after initial treatment were created. In addition, an actuarial curve for survival after detection of metastatic uveal melanoma was computed for the patients in the series who developed metastasis. Data analysis was completed with SPSS version 7.0 (IBM). Statistical significance was defined as P < .05 (2-sided).

Results

Of 2265 patients with PUM who were encountered during the study interval, 18 patients (0.8%) were younger than 21 years when diagnosed and treated. The baseline clinical features of the patients and tumors in these 18 patients are presented in raw form in Table 1 and in summary form in Table 2.

Table 1. Raw Data on 18 Patients With Posterior Uveal Melanoma Who Were Younger Than 21 Years of Age at Treatment.

| Patient No./Sex/Age, ya | Eyes | Best-Corrected Visual Acuity | Tumor Site | Largest Basal Diameter, mm | Thickness, mmb | TNM Tumor Size | Extrascleral Extension of Tumor | TNM Stage | Treatmentc | Melanoma Cell Type | Uveal Melanoma Metastasis | Interval to Metastasis, y | Death | Total Follow-up, y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/F/4 | OS | No light perception | Ciliochoroidal | 24.0 | 16.0 | T4 | Yes | 3C | Enucleation | Epithelioid | Yes | 0.15 | Yes | 0.2 |

| 2/F/8 | OS | Counting fingers | Ciliochoroidal | 15.0 | 11.1 | T3 | No | 3A | Enucleation | Mixed | No | 16.1 | No | 16.1 |

| 3/M/14 | OD | Hand motion | Choroidal | 14.0 | 12.1 | T3 | No | 2B | Enucleation | Mixed | Yes | 3.7 | Yes | 3.9 |

| 4/F/14 | OD | 20/30 | Ciliochoroidal | 11.0 | 11.6 | T3 | No | 3A | Resection | Spindle | No | 11.3 | No | 11.3 |

| 5/F/16 | OS | 20/25 | Ciliochoroidal | 8.0 | 7.0 | T2 | No | 2B | Resection | Mixed | No | 16.8 | No | 16.8 |

| 6/M/16 | OS | 20/20 | Choroidal | 15.0 | 4.5 | T2 | No | 2A | Plaque | Not applicable | Yes | 1.3 | Yes | 2 |

| 7/F/16 | OD | 20/25 | Ciliochoroidal | 12.0 | 8.2 | T2 | No | 2B | Enucleation | Mixed | No | 3.8 | No | 3.8 |

| 8/M/16 | OD | 20/60 | Choroidal | 12.5 | 3.7 | T2 | No | 2A | Plaque | Not applicable | No | 3.0 | No | 3.0 |

| 9/M/17 | OS | 20/100 | Choroidal | 8.5 | 3.0 | T1 | No | 1 | Plaque | Not applicable | Yes | 4.7 | Yes | 5 |

| 10/M/17 | OS | 20/100 | Choroidal | 10.0 | 3.1 | T2 | No | 2A | Enucleation | Spindle | Yes | 4.5 | Yes | 4.7 |

| 11/F/18 | OD | 20/70 | Choroidal | 15.5 | 10.1 | T4 | No | 3A | Enucleation | Spindle | Yes | 8.4 | Yes | 11.9 |

| 12/M/18 | OD | 20/70 | Choroidal | 8.5 | 5.2 | T1 | No | 1 | Proton beam irradiation | Not applicable | No | 7.1 | No | 7.1 |

| 13/F/18 | OS | 20/100 | Choroidal | 6.5 | 3.6 | T2 | No | 1 | Plaque | Not applicable | Yes | 8.1 | Yes | 8.8 |

| 14/F/19 | OS | 20/200 | Choroidal | 6.5 | 3.6 | T1 | No | 1 | Enucleation | Spindle | No | 6.0 | No | 6.0 |

| 15/F/19 | OS | Light perception | Choroidal | 16.0 | 6.0 | T3 | No | 2B | Enucleation | Mixed | Yes | 9 | Yes | 9 |

| 16/F/20 | OD | 20/50 | Choroidal | 9.5 | 7.0 | T2 | No | 2A | Plaque | Not applicable | No | 4.9 | No | 4.9 |

| 17/M/20 | OD | 20/400 | Ciliochoroidal | 15.0 | 10.1 | T3 | No | 3A | Resection | Mixed | No | 21.5 | No | 21.5 |

| 18/M/20 | OD | 20/100 | Choroidal | 13.0 | 8.5 | T3 | No | 2B | Enucleation | Spindle | No | 17.5 | No | 17.5 |

Patients are listed in order from youngest to oldest.

Indicates maximal thickness of primary intraocular tumor.

Plaque indicates eye plaque radiotherapy; resection, transcleral en bloc resection of tumor.

Table 2. Summary Data on Baseline Ocular and Tumor Variables in 18 Patients With Primary PUM Who Were Younger Than 21 Years When Treated.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 8 (44) |

| Female | 10 (56) |

| Age of patients, mean (SD) [range], y | 16.6 (4.2) [4.4-20.8] |

| Eye | |

| Right | 9 (50) |

| Left | 9 (50) |

| Best corrected visual acuity in affected eyea | |

| 20/40 or Better | 4 (22) |

| 20/50 to 20/100 | 8 (44) |

| 20/200 or Worse | 6 (33) |

| Tumor site | |

| Exclusively choroidal | 12 (67) |

| Ciliochoroidal | 6 (33) |

| TNM tumor size | |

| T1 | 3 (17) |

| T2 | 7 (39) |

| T3 | 6 (33) |

| T4 | 2 (11) |

| Categorical distance between tumor and foveola | |

| Subfoveal | 3 (17) |

| Not subfoveal but ≤3 mm from foveola | 3 (17) |

| >3 mm From foveola | 12 (67) |

| Categorical distance between tumor and optic disc | |

| Extends to optic disc margin | 3 (17) |

| Not extending to optic disc margin but ≤3 mm from optic disc | 6 (33) |

| >3 mm From optic disc margin | 9 (50) |

| Extrascleral extension of tumor | |

| Absent | 17 (94) |

| Presentb | 1 (6) |

| TNM stage of posterior uveal melanoma | |

| I | 4 (22) |

| II | 9 (50) |

| III | 5 (28) |

| IV | 0 |

| Largest basal diameter of tumor, mean (SD) [range], mm | 12.8 (4.6) [6.5-24] |

| Thickness of tumor, mean (SD) [range], mm | 7.2 (3.6) [3-16] |

Snellen equivalent.

In the 1 case that exhibited extrascleral extension of tumor at diagnosis, that extension was more than 10 mm in both diameter and thickness.

The mean (SD) age of the 18 patients with PUM at time of treatment was 16.6 (4.2) years, with a minimum age of 4.4 years and a maximum age of 20.8 years. Just 1 patient in this group was younger than 5 years of age (6%), and 1 other patient was younger than 10 years of age (6%). Two patients in the group were between 10 and 15 years of age (11%), and the remaining 14 patients (78%) were all older than 15 years. Ten of the 18 patients (56%) were female.

The right eye was affected in 9 patients (50%). The best-corrected distance visual acuity of affected eyes at the pretreatment examination was better than 20/50 in 4 patients (22%), between 20/50 and 20/200 in 8 patients (44%), and 20/200 or worse in 6 patients (33%).

The mean (SD) largest basal diameter of the tumor was 12.8 (4.6) mm, and the mean maximal tumor thickness was 7.2 (3.6) mm. The tumor size category according to the TNM classification system, seventh edition,13 was T1 in 3 cases (17%), T2 in 7 cases (39%), T3 in 6 cases (33%), and T4 in 2 cases (11%). None of the patients in this group had detectable metastasis on their baseline systemic evaluation prior to treatment. The stage of the PUM at baseline according to the TNM classification system, seventh edition,13 was stage 1 in 4 cases (22%), stage 2 in 9 cases (50%), and stage 3 in 5 cases (28%).

The intraocular tumor was exclusively choroidal in 12 eyes (67%) and involved the ciliary body in 6 eyes (33%). Three of the tumors (17%) extended posteriorly to the optic disc, 6 (33%) had a posterior margin not extending to the optic disc but within 3 mm of the disc, and 9 tumors (50%) were more than 3 mm away from the optic disc. Three of the tumors (17%) were subfoveal, 3 (17%) were extrafoveal but extended to within 3 mm of the foveola, and 12 (67%) were more than 3 mm away from the foveola.

None of these patients had a family history of uveal melanoma or BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome. Only 1 of the 18 tumors exhibited oculodermal melanocytosis; coincidentally, this was the most advanced tumor in this series, presenting with extrascleral extension (case 1 in Table 1). This unusual case has been reported separately.14

Patients were treated with enucleation of the affected eye in 9 cases (50%), plaque radiotherapy in 5 cases (28%), transscleral en bloc resection in 3 cases (17%), and proton beam irradiation in 1 case (6%). The tumor was evaluated histopathologically in the 12 cases that were managed by enucleation or transscleral tumor extension. This evaluation confirmed the diagnosis of uveal melanoma in each of these cases and identified the tumor cell type as spindle in 5 cases (42%), mixed in 6 cases (50%), and epithelioid in 1 case (8%).

The mean (SD) posttreatment follow-up time among the 18 patients with PUM was 8.5 (6.1) years, with a minimum follow-up of 0.2 years and a maximum follow-up of 21.5 years. The median posttreatment follow-up time of patients who were still living at the time of data analysis was 9.2 years.

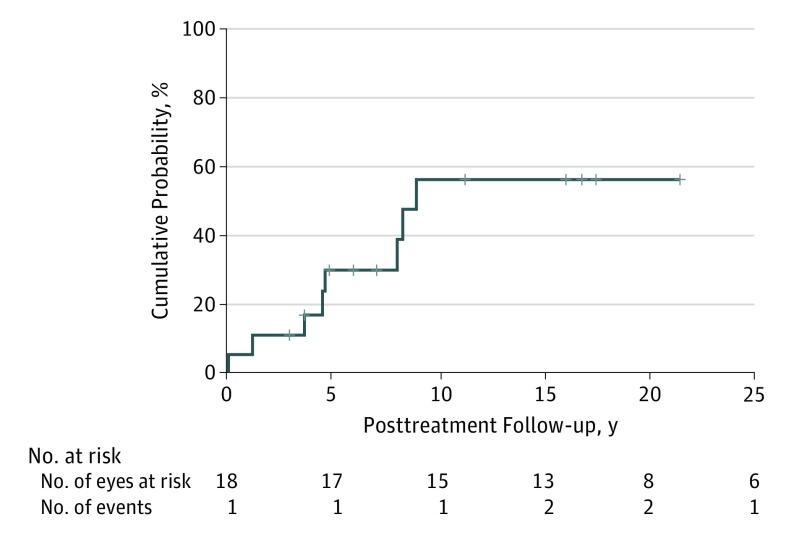

Figure 1 shows the actuarial (Kaplan-Meier) event rate curve for metastasis in the full group of patients. The cumulative percentage of patients who had developed metastasis was 11% at 3 years (n = 2), 30% at 5 years (n = 5), and 56% at 10 years (n = 8). The median metastasis-free survival time in the group was 9.0 years (95% CI, 7.6-10.4 years).

Figure 1. Actuarial Event Rate Curve for Metastasis in 18 Patients After Posterior Uveal Melanoma Treatment.

Median survival, 9.0 years (95% CI, 7.6-10.4 years; 95% CI around the cumulative probability of 50%: z score, 0.23-0.77).

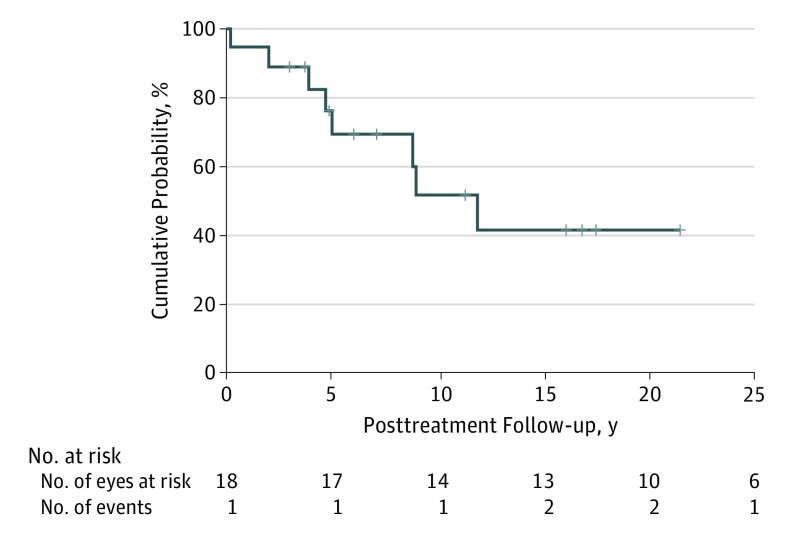

Figure 2 shows the actuarial (Kaplan-Meier) survival curve based on deaths from metastasis in the full group. The cumulative percentage of patients dying of metastasis was 11% at 3 years (n = 2), 31% at 5 years (n = 5), 48% at 10 years (n = 7), and 58% at 15 years (n = 8). The median survival time of these patients was 11.9 (95% CI, 7.3-16.5) years. Because all of the patients who developed metastasis died of their metastasis and no patient who did not develop metastasis died of any other cause during available follow-up, this curve is identical to the overall survival curve for this group.

Figure 2. Actuarial (Kaplan-Meier) Survival of 18 Patients After Posterior Uveal Melanoma Treatment.

Median survival, 11.9 years (95% CI, 7.3-16.5 years; 95% CI around the cumulative probability of 50%: z score, 0.23-0.78).

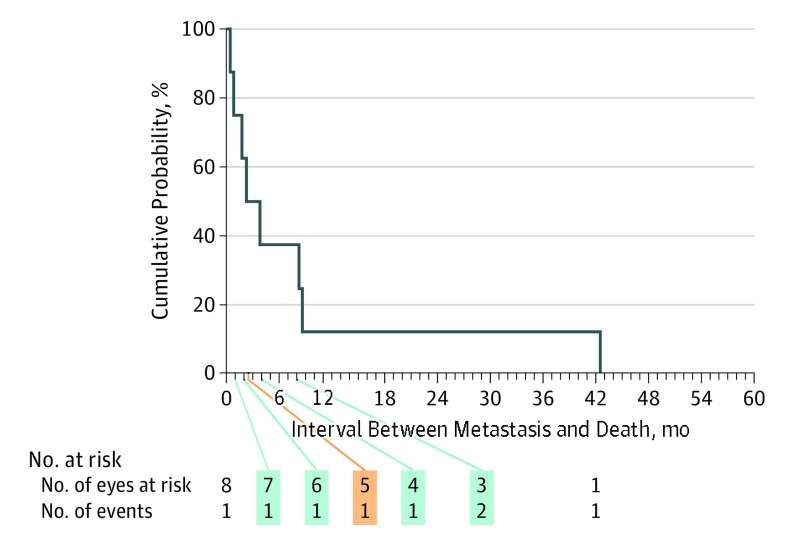

Figure 3 shows the actuarial (Kaplan-Meier) survival curve of the 8 patients who developed metastatic uveal melanoma after detection of that metastasis. The curve documents a median survival time after detection of metastasis in this group of only 2.3 months (95% CI, 0.0-5.2 months). Only 1 of the patients survived for more than 1 year after detection of metastatic uveal melanoma.

Figure 3. Actuarial (Kaplan-Meier) Survival of 8 Patients Who Died After Metastatic Uveal Melanoma Detection.

Median, 2.3 months (95% CI, 0.0-5.2 months; 95% CI around the cumulative probability of 50%: z score, 0.15-0.85).

Discussion

Uveal melanoma is an uncommon malignant intraocular neoplasm, affecting only about 1 in 2000 to 2500 persons during their lifetimes.8,9 Although the average annual incidence of this malignant neoplasm across all age groups has been estimated to be about 5 to 8 new cases per million persons per year,2,3 the curve of annual incidence by decade of life is extraordinarily low prior to the fourth decade, and then it rises abruptly to approximately 50 new cases per million persons per year by the eighth decade of life.1,2 Patients younger than 21 years can develop primary uveal melanoma, but they do so much less frequently than adults.4,5 Compared with middle-aged and older adults with uveal melanoma, young patients also have historically presented with a greater proportion of iris melanoma rather than PUM.5,8 In our single-practice experience, only 18 of 2265 patients (0.8%) with PUM were younger than 21 years. Given the rarity of this presentation, our group decided to review this clinical experience and present clinical features of PUM among young patients, defined as individuals diagnosed with PUM before the age of 21 years.

Before discussing survival prognosis, it is interesting to highlight that in this series of young patients with PUM, enucleation was performed as initial treatment in 50% of the cases and transscleral en bloc tumor resection was performed in 17% of cases. Both of these frequencies are substantially higher than those in the older patient subgroups in our practice. We acknowledge the meaningful concerns most parents and guardians have about long-term effects of radiation therapy to the eye in young patients, and we suspect that this concern explains some of the shift toward excisional primary therapies and away from focal radiation therapy methods in this subgroup.

The observed actuarial probabilities of metastasis and metastatic death in any given population of patients with PUM depend on a number of clinical and pathologic determinable factors.10,11,12,13,14,15 The number of patients and deaths in this small series of cases was insufficient for multivariate analysis and identification of any prognostic factors in this subgroup. Interestingly, 1 child in this group (case 1 in Table 1) had very advanced disease with extraocular extension and oculodermal melanosis.14 Despite the aggressive presentation and the acute development of metastatic disease, the gene expression profile in this patient was class 1B.15,16

Most patients in this study (n = 16 of 18 [89%]) were in their teenage years (13.1 to ≤20 years) when diagnosed with PUM. This finding is consistent with the observation that most patients with uveal melanoma who are young have experienced or are experiencing puberty at the time of diagnosis.8

In other reported studies of age-unselected cases of posterior uveal melanoma, younger patient age at the time of diagnosis and treatment has frequently been identified as a favorable prognostic factor for 5-year metastasis-free survival in multivariate analysis.5,8,17,18 Because this was shown by other researchers, the expectation in this analysis was to find a substantially better metastasis and survival outcome in this subgroup compared with older patients, despite the management method used for their PUM.5,8,17,18 Because we did not find evidence of BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome and only 1 patient that had oculodermal melanosis, there are only few explanations as to the findings of this analysis compared with other reports. First, because young people who develop a PUM have fewer competing risks for death than elderly persons with the same type of tumor, young people appear to have a higher long-term cumulative probability of death from metastasis than older persons do. Second, unlike other series that included patients with iris tumors, who have an overall better prognosis, all of our patients had PUM.5,8,17 Those may be the reasons why this group of patients had a higher number of events compared with other studies’ reports of lower rates of metastasis.8,17,18 However, 1 study that found a lower frequency of young patients with posterior uveal melanoma (only 17 of 3207 patients ≤20 years of age [0.5%]) treated with proton beam irradiation showed no deaths or development of metastasis during a long follow-up period (median, 16 [range, 4.7-25.2] years) that was comparable with ours.18

In our group of patients younger than 21 years, a substantial proportion developed metastasis (Figure 1) and died of that metastasis (Figure 2) during available follow-up. Notably, 3 of the 8 patients who developed metastasis in this group did not show evidence of that metastasis until after the fifth posttreatment year. Recognizing that PUM metastasis has been documented to emerge in some patients more than 10 years and occasionally even more than 20 years after enucleation,19 we suspect that some of the surviving patients in this group may ultimately develop clinically detectable metastasis during longer-term follow-up. What this tells us is that young persons who appear to be survivors of PUM for 5 years or longer posttreatment should not be assured of an ultimate cure. Clinicians should advise such patients and their families about the potential for late emergence of uveal melanoma metastasis after an extended latent interval posttreatment.

Limitations

This study, similar to others looking at this particular age group of patients with PUM, has the limitation of being retrospective and lack of genomic information of these tumors that could potentially give insights to prognosis and survival, thus limiting our ability to fully understand why this patient group had a rate of survival comparable with that of adult patients. To better determine metastatic risk and patient survival probabilities, future studies should include gene expression profile testing and next-generation sequencing for mutation analysis of these tumors.11,15,16 Another important limitation is the small sample size, which is associated the rarity of this occurrence; this does not allow multivariate analysis to provide more insight into this group.

Conclusions

In summary, this study suggests that PUM in patients younger than 21 years has equally bad if not worse prognosis compared with that of patients with PUM in the population overall, and the onset of metastasis seems to occur later than in older patients. Such finding suggests that, unlike the care usually recommended for older patients with PUM, young patients should continue to be monitored by routine surveillance tests for more than 10 years.

References

- 1.Andreoli MT, Mieler WF, Leiderman YI. Epidemiological trends in uveal melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(11):1550-1553. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh AD, Turell ME, Topham AK. Uveal melanoma: trends in incidence, treatment, and survival. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(9):1881-1885. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, Martin HJ, Roche LM, Chen VW. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer. 2005;103(5):1000-1007. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr CC, McLean IW, Zimmerman LE. Uveal melanoma in children and adolescents. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(12):2133-2136. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930021009003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Furuta M, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Clinical spectrum and prognosis of uveal melanoma based on age at presentation in 8,033 cases. Retina. 2012;32(7):1363-1372. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31824d09a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan KM, Seddon JM, Glynn RJ, Gragoudas ES, Albert DM. Epidemiologic aspects of uveal melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32(4):239-251. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90173-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iscovich J, Ackerman C, Andreev H, Pe’er J, Steinitz R. An epidemiological study of posterior uveal melanoma in Israel, 1961-1989. Int J Cancer. 1995;61(3):291-295. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaliki S, Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Ganesh A, Furuta M, Shields JA. Influence of age on prognosis of young patients with uveal melanoma: a matched retrospective cohort study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23(2):208-216. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krantz BA, Dave N, Komatsubara KM, Marr BP, Carvajal RD. Uveal melanoma: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of primary disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:279-289. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S89591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augsburger JJ, Gamel JW. Clinical prognostic factors in patients with posterior uveal malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1990;66(7):1596-1600. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrêa ZM, Augsburger JJ. Independent prognostic significance of gene expression profile class and largest basal diameter of posterior uveal melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;162:20-27.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Affeldt JC, Minckler DS, Azen SP, Yeh L. Prognosis in uveal melanoma with extrascleral extension. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98(11):1975-1979. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020040827006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AJCC Ophthalmic Oncology Task Force International validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s 7th edition classification of uveal melanoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(4):376-383. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray ME, Shaikh AH, Corrêa ZM, Augsburger JJ. Primary uveal melanoma in a 4-year-old black child. J AAPOS. 2013;17(5):551-553. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onken MD, Worley LA, Char DH, et al. Collaborative Ocular Oncology Group report number 1: prospective validation of a multi-gene prognostic assay in uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(8):1596-1603. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decatur CL, Ong E, Garg N, et al. Driver mutations in uveal melanoma: associations with gene expression profile and patient outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(7):728-733. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrovic A, Bergin C, Schalenbourg A, Goitein G, Zografos L. Proton therapy for uveal melanoma in 43 juvenile patients: long-term results. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):898-904. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vavvas D, Kim I, Lane AM, Chaglassian A, Mukai S, Gragoudas E. Posterior uveal melanoma in young patients treated with proton beam therapy. Retina. 2010;30(8):1267-1271. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cfdfad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolandjian NA, Wei C, Patel SP, et al. Delayed systemic recurrence of uveal melanoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(5):443-449. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182546a6b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]