Abstract

Importance

The association of nasal airway obstruction with health is significant, and the health care resources utilized in open septorhinoplasty need to be included in health economic analyses.

Objectives

To describe the association of nasal airway obstruction and subsequent open septorhinoplasty with patient health.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A prospective case series study was conducted from September 30, 2009, to October 29, 2015, at 2 tertiary rhinologic centers in Sydney, Australia, among 144 consecutive adult patients (age, ≥18 years) with nasal airway obstruction from septal and nasal valve disorders.

Interventions

Open septorhinoplasty.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patients were assessed before undergoing open septorhinoplasty and then 6 months after the procedure. Health utility values (HUVs) were derived from the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey. Nasal obstruction severity was also measured using the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) questionnaire and the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 questionnaires.

Results

A total of 144 patients (85 women and 59 men; mean [SD] age, 38 [13] years) were assessed. The baseline mean (SD) HUV for patients in this study was 0.72 (0.09), which was below the weighted mean (SD) Australian norm of 0.81 (0.22). After open septorhinoplasty, the mean (SD) HUV improved to 0.78 (0.12) (P < .001). Improvements in HUV were associated with changes in disease-specific patient-reported outcome measures, including Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation scores (r = –0.48; P = .01) and Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 scores (r = −0.68; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients with nasal airway obstruction reported baseline HUVs that were lower than the Australian norm and similar to those in individuals with chronic diseases with significant health expenditure. There was a clinically and statistically significant improvement in HUVs after open septorhinoplasty that was associated with a reduction in Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation and Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 scores. Outcomes from this study may be used for health economic analyses of the benefit associated with open septorhinoplasty.

Level of Evidence

4.

This case series study examines the association of nasal airway obstruction and subsequent open septorhinoplasty with health outcomes in Australia.

Key Points

Question

What is the association of nasal airway obstruction and subsequent open septorhinoplasty with health utility values?

Findings

In this case series study, health utility values of 144 patients with nasal airway obstruction who underwent open septorhinoplasty were assessed before and 6 months after the procedure; baseline health utility values were lower than the Australian norm and similar to those in individuals with chronic diseases with significant health expenditure. There was a clinically and statistically significant improvement in health utility values after open septorhinoplasty.

Meaning

The findings suggest that nasal airway obstruction is associated with health outcomes and that open septorhinoplasty may be clinically beneficial for improving health outcomes.

Introduction

Nasal airway obstruction encompasses several conditions that hinder airflow of the nose, with causes such as septal deviation, nasal valve collapse, turbinate hypertrophy, and rhinitis. It is a common condition in otolaryngology practice and can have significant effects on sinonasal function and overall health.1 Despite its prevalence and high costs to the health care system, nasal airway obstruction and its treatment remain difficult to assess because objective measures do not necessarily correlate with patients’ perception of nasal function.2,3,4,5 Thus, disease-specific patient-reported outcome measures, such as the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE), have become the primary metric by which the burden of nasal airway obstruction is measured and outcomes after treatment are assessed.6

Owing to increasing pressure for health care systems to allocate their limited resources, decision makers are required to critically evaluate the benefits and cost-effectiveness of medical and surgical interventions. The value of the additional time and resources that are required in open septorhinoplasty is often questioned. However, the value of an intervention can be assessed through health utility values (HUVs), a measure of preference-based health-related quality of life (QOL) that is often used by health economists in cost-utility analyses.7 Furthermore, HUVs measure patient-reported outcomes in a common metric, allowing comparison between different chronic disease states.8,9 At present, evidence is limited on the effect of nasal airway obstruction, its effect as measured by HUVs, and the effect of open septorhinoplasty on HUVs in patients with nasal airway obstruction.

The aim of this study was to assess the association of nasal airway obstruction from septal and nasal valve disorders with health outcomes as measured by HUVs and the subsequent association of open septorhinoplasty with patient health.

Methods

Study Design

In this case series study, consecutive adult patients (age, ≥18 years) with nasal airway obstruction from septal and nasal valve disorders who elected for open septorhinoplasty from September 30, 2009, to October 29, 2015, were assessed at 2 tertiary rhinologic centers in Sydney, Australia. Patients younger than 18 years at the time of diagnosis were excluded. Patient data were deidentified. Ethics approval was granted by St. Vincent’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, Sydney, Australia (SVH 09/083). Patients provided informed consent.

Patients underwent open septorhinoplasty with or without turbinate reduction for nasal airway obstruction. All patients were determined by the treating surgeon to have a significant septal and/or nasal valve deformity through clinical examination, medical imaging, or a combination of both. Patients completed standardized patient-reported outcome measures, including the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey v2 Australia (SF-36), the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 (SNOT-22), and the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) questionnaire, before and 6 months after the procedure.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Nasal airway obstruction was assessed using a visual analog scale from 0 to 100 mm and the NOSE questionnaire.10 The NOSE questionnaire is a 5-item survey developed to assess the subjective consequences of nasal airway obstruction in general, with each question scaled from 0 to 100, with higher numbers representing poorer health. The SNOT-22 was recorded as a disease-specific, patient-reported outcome measure of the prior 2 weeks of symptoms and has been described in the context of nasal airway obstruction.11,12 Scores on the SNOT-22 are scaled from 0 to 120, with higher numbers representing a significant problem to a patient’s life. All patients completed an SF-36 QOL questionnaire.13 The SF-36 is a generic patient-reported outcome measure, whereas the SNOT-22 and the NOSE questionnaire evaluate disease-specific QOL for nasal airway obstruction. The SF-36 questionnaire provides a physical component score and mental component score for each patient. After patients were given a decongestant, they completed the questionnaires in a quiet and comfortable environment while waiting for the decongestant to take effect before their consultation. Assistance was provided if clarifications were required, and more time was given as necessary to ensure full completion of the questionnaires.

HUV Assessment

Data from the SF-36, which was completed by patients before and after open septorhinoplasty, were converted into a Short Form 6D (SF-6D) utility score and HUVs using a weighted algorithm that was used with permission from the Department of Health Economics and Decision Science, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom. The algorithm generates the SF-6D utility score using a set of preference weights obtained from a sample of the Australian general population through the standard gamble technique.14,15,16 The SF-6D is a validated classification system to describe health states derived from the SF-36, comprising 6 multilevel dimensions. Patients are classified into 1 of 18 000 health states depending on their individual response. Each health state can then be translated into HUVs. This process allows the SF-6D to provide the means to obtain quality-adjusted life years from the SF-36, which can be used in cost-utility analyses to determine where health care resources should be most efficiently directed.17 Health utility values are measured from a scale of 0 to 1, where 0 represents death and 1 represents perfect health. Measurements are placed on an interval scale, which means that changes are the same irrespective of where the HUVs are placed (for example, a change in HUV from 0.3 to 0.4 is equivalent to a change from 0.7 to 0.8). A change of 0.03 or more in HUV is regarded as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for a particular health state.18

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS statistics software, version 24.0 (SPSS Inc). Results are presented as mean (SD). Correlation between HUVs and baseline variables was performed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The correlation coefficient (r score) obtained from the Pearson correlation test is stratified into weak (<0.3), moderate (0.3-0.5), and strong (>0.5). Differences in baseline variables and HUVs after surgery were analyzed using a paired t test. P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant, with 95% CIs.

Results

A total of 144 patients (85 women and 59 men; mean [SD] age, 38 [13] years) were assessed. Baseline demographic data, patient-reported outcome measure results, and HUVs are presented in Table 1. The mean (SD) HUV for this patient population before nasal surgery was 0.72 (0.09), which was lower than the weighted mean (SD) norm of the Australian population of 0.81 (0.22).19

Table 1. Baseline Patient Demographics and Patient-Reported Outcomesa.

| Variable | Value (N = 144)b |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 38 (13) |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 85 (59.0) |

| VAS, obstructed side | 61.91 (22.46) |

| NOSE | 48.12 (17.40) |

| SNOT-22 | 37.84 (20.46) |

| SF-36 PCS | 51.32 (8.87) |

| SF-36 MCS | 44.79 (11.43) |

| HUV before procedure | 0.72 (0.09) |

Abbreviations: HUV, health utility value; NOSE, Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation; SF-36 MCS, Short Form-36 mental component score; SF-36 PCS, Short Form-36 physical component score; SNOT-22, Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22; VAS, visual analog scale.

Details on scores are given in the Methods section.

Data are mean (SD) value unless otherwise indicated.

Association of HUVs With Other Measures of Disease Severity

Correlation between HUVs and other patient-reported outcome measures was assessed (Table 2). Moderate to strong correlations were seen between HUVs and patients’ perception of nasal patency derived from patient-reported outcome measures. Higher visual analog scale scores on the obstructed side (r = –0.38; P = .01) and higher NOSE scores (r = –0.48; P = .01) and SNOT-22 scores (r = –0.68; P = .01) (indicative of a subjectively higher degree of nasal obstruction) were correlated with lower HUVs, thus reflecting poorer QOL.

Table 2. Correlation of Baseline HUVs With Age and Other Patient-Reported Outcomesa.

| Correlation With HUV | r Score | Strength | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.48 | NA | .57 |

| VAS, obstructed side | −0.38 | Moderate | .01 |

| NOSE | −0.48 | Moderate | .01 |

| SNOT-22 | −0.68 | Strong | .01 |

| SF-36 PCS | 0.48 | Moderate | .01 |

| SF-36 MCS | 0.77 | Strong | .01 |

Abbreviations: HUV, health utility value; NA, not applicable; NOSE, Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation; SF-36 MCS, Short Form-36 mental component score; SF-36 PCS, Short Form-36 physical component score; SNOT-22, Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22; VAS, visual analog scale.

Details on scores are given in the Methods section.

Pearson correlation test was used for statistical analysis.

Association of Open Septorhinoplasty With HUVs

A significant improvement in mean (SD) HUVs was seen 6 months after open septorhinoplasty (from 0.72 [0.12] to 0.78 [0.12]; P < .001). There was an appreciable change in HUVs after open septorhinoplasty, given that the MCID of an intervention for a particular health state was defined as 0.03 or more. Follow-up data also showed significant improvements in patient-reported QOL measures after open septorhinoplasty, particularly in mean (SD) visual analog scale scores on the obstructed side (from 62.89 [21.90] to 31.92 [26.28]; P < .001), NOSE scores (from 48.22 [19.23] to 24.44 [22.63]; P < .001), and SNOT-22 scores (from 37.17 [19.14] to 20.68 [17.38]; P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Association of Open Septorhinoplasty With Symptoms and Healtha.

| Characteristic | Score, Mean (SD) | Change in Score, Mean (SD) [95% CI] | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperative | |||

| VAS, obstructed side | 62.89 (21.90) | 31.92 (26.28) | −30.91 (23.31) [−25.52 to −36.39] | <.001 |

| NOSE | 48.22 (19.23) | 24.44 (22.63) | −23.78 (15.92) [−14.91 to −31.24] | <.001 |

| SNOT-22 | 37.17 (19.14) | 20.68 (17.38) | −16.49 (10.37) [−10.96 to −20.32] | <.001 |

| SF-36 PCS | 50.57 (9.23) | 53.59 (7.47) | 3.02 (0.72) [2.67 to 3.29] | <.001 |

| SF36 MCS | 45.05 (11.31) | 48.39 (10.79) | 3.34 (1.65) [1.61 to 5.07] | <.001 |

| HUV | 0.72 (0.12) | 0.78 (0.12) | 0.06 (0.02) [0.05 to 0.07] | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HUV, health utility value; NOSE, Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation; SF-36 MCS, Short Form-36 physical component score; SF-36 PCS, Short Form-36 physical component score; SNOT-22, Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22; VAS, visual analog scale.

Details on scores are given in the Methods section.

Paired t test was used for statistical analysis.

Discussion

Many disease-specific, patient-reported outcome measures, including the SNOT-22 and NOSE questionnaires, have been validated and used in rhinologic studies to evaluate the effectiveness of medical and surgical interventions for nasal airway obstruction.6,20,21 However, only a few studies have used generic patient-reported outcome measures, such as the SF-6D, to generate HUVs and evaluate the disease burden of nasal airway obstruction. Potentially, the change in health status of patients with nasal airway obstruction might be too subtle or disease specific to be assessed using the contents of a generic patient-reported outcome measure.10

Health utility values are unique because they quantify an individual’s preference for their state of health. Unlike disease-specific outcome measures, such as the SNOT-22 and NOSE questionnaires, HUVs provide a general QOL metric that allow comparison between various chronic disease states and interventions. Health utility values form the basis by which quality-adjusted life years are derived, and calculation of cost per quality-adjusted life year is then used to assess the cost-effectiveness of treatments. A change of 0.03 in HUVs has been validated among many chronic disease states to indicate MCID that changes a patient’s subjective well-being by at least 1 point on a 5-point global health rating of change (where 5 is much better health; 4, somewhat better health; 3, no change in health; 2, somewhat poorer health; and 1, much poorer health).22

This patient population with nasal airway obstruction from septal and nasal valve disorders demonstrated a significant improvement in SF-6D–derived HUVs after open septorhinoplasty that was in excess of the MCID. This finding suggests that open septorhinoplasty is associated with improvement in the subjective overall health state experienced by patients with nasal airway obstruction. Studies on patients with chronic rhinosinusitis have also shown improvement in HUVs after endoscopic sinus surgery.23,24,25 Mean (SD) preoperative HUVs of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis from 2 studies were 0.67 (0.11)24 and 0.70 (0.15),25 which was slightly poorer than that in our study, at 0.72 (0.09).

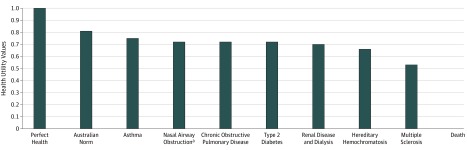

Before open septorhinoplasty, baseline mean (SD) HUVs of patients with nasal airway obstruction were significantly lower than the Australian norm (0.72 [0.09] vs 0.81 [0.22]).19 The HUV impairment is similar to that seen with other chronic diseases in the Australian population (Figure), which include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (0.72), diabetes mellitus (0.72), and renal disease requiring dialysis (0.70).19,26,27,28,29,30 Furthermore, the degree of improvement after open septorhinoplasty (mean [SD], 0.06 [0.02]) has been found to be more clinically significant than the use of continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea (0.04) and comparable to total ankle arthroplasty (0.06) and joint replacement surgery (0.06).31,32,33 This finding further reveals the extent of disease burden that patients with nasal airway obstruction can experience.

Figure. Comparison of Short Form-6D–Derived Health Utility Values Between Different Chronic Disease States in Australia.

aThe disease burden of nasal airway obstruction was significant.

Health utility values in this study were not directly obtained through SF-6D questionnaires but rather through the conversion of SF-36 data to SF-6D scores using a program from the University of Sheffield. The conversion was necessary to obtain HUVs; the SF-36 is not suitable for cost-utility analysis because it assumes that each item is of equal importance and does not enable tradeoffs between different dimensions of health (for instance, between quality and length of life or pain and physical functioning). The SF-6D, an abbreviated version of the SF-36, was designed to incorporate preference weights to each individual health state for use in cost-utility analysis. Preference weights were obtained from standard gamble health state valuation tasks completed by a large sample of the Australian population.34 These valuations were fit in an ordinary least-squares regression to create an equation that can be used to convert any combination of the 6 domain levels to generate an SF-6D–derived HUV.14 The conversion algorithm has been validated to reduce the mean absolute error of sample predictions and overcome bias of regression models in underpredicting poorer health states, therefore mitigating the inherent weakness of mapping the results from the SF-36.15,16 Moreover, this conversion algorithm has been used in other areas of health, including peripheral vascular and rheumatologic diseases.35,36

Strengths and Limitations

The SF-36 was selected as the generic patient-reported outcome measure for this study because its psychometric properties are well established and it is widely used throughout the world.37 In addition, the SF-36 has a large descriptive system and is thus believed to have a greater degree of sensitivity.15,38 Several organizations, including the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Bureau of Statistics, have adopted the use of the SF-36 to gather health data on a nationally representative population sample.39 Application of the SF-36 in this study provided quantitative data that showed a benefit of open septorhinoplasty for generic patient-reported outcome measures and is a step toward future studies in cost-utility analysis.

With the results of this study, it must be taken into account that patient comorbidities were excluded in data collection; therefore, it is difficult to determine the contribution of other medical conditions and to isolate the effect of nasal airway obstruction to each individual patient. However, this study demonstrated an improvement in health (as defined by HUVs) and QOL regardless of comorbidities in a young patient population. The change in NOSE score after surgical intervention in this study did not reach the MCID of 30 or more. Regardless, the mean postoperative NOSE score was similar to the reported mean postoperative NOSE score of patients with nasal airway obstruction.6

In addition, there is a lack of generalizability in this patient population because patients who underwent nasal surgery were recruited from specialized tertiary rhinologic centers. These patients may represent a specific group of patients with potentially more severe manifestations of nasal airway obstruction and may not be an accurate reflection of disease severity for an average patient with nasal airway obstruction.

A significant challenge in the interpretation of published utility values is the presence of other QOL instruments from which HUVs can be derived, such as the EuroQOL 5-Dimension, Health Utilities Index Mark 3, and Quality of Well-Being Index. Health utility values derived from different QOL instruments are not interchangeable owing to differing conceptualization, content, and methods.40,41 For instance, the mean (SD) HUV of the Australian population resulting from the SF-6D was in contrast with values resulting from the EuroQOL 5-Dimension.42 Direct comparisons between HUVs derived from the SF-36 and EuroQOL 5-Dimension in nasal airway obstruction have yet to be described in the literature, to our knowledge. However, one study using the EuroQOL 5-Dimension visual analog scale score was able to detect a clinically significant improvement after functional septorhinoplasty for nasal airway obstruction.43 Furthermore, both instruments show comparable gains in utility after endoscopic sinus surgery in the context of chronic rhinosinusitis, supporting the use of each instrument in cost-utility analysis.25,44

Conclusions

Patients with nasal airway obstruction in this study reported baseline HUVs that were lower than the Australian norm and comparable with those for individuals with chronic diseases with significant health expenditure. There was a clinically and statistically significant improvement in HUVs after surgical intervention that correlated with a reduction in NOSE and SNOT-22 scores. Outcomes from this study may be used for health economic analyses of the benefit associated with open septorhinoplasty.

References

- 1.Jessen M, Malm L. Definition, prevalence and development of nasal obstruction. Allergy. 1997;52(40)(suppl):3-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb04876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yaniv E, Hadar T, Shvero J, Raveh E. Objective and subjective nasal airflow. Am J Otolaryngol. 1997;18(1):29-32. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(97)90045-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhee JS, Book DT, Burzynski M, Smith TL. Quality of life assessment in nasal airway obstruction. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(7):1118-1122. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200307000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawar SS, Garcia GJ, Kimbell JS, Rhee JS. Objective measures in aesthetic and functional nasal surgery: perspectives on nasal form and function. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26(4):320-327. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohan S, Fuller JC, Ford SF, Lindsay RW. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of nasal airway obstruction: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(5):409-418. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee JS, Sullivan CD, Frank DO, Kimbell JS, Garcia GJ. A systematic review of patient-reported nasal obstruction scores: defining normative and symptomatic ranges in surgical patients. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16(3):219-225. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2013.2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal. J Health Econ. 1986;5(1):1-30. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90020-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudmik L, Drummond M. Health economic evaluation: important principles and methodology. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(6):1341-1347. doi: 10.1002/lary.23943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Gandek B, et al. The factor structure of the SF-36 Health Survey in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project: international quality of life assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1159-1165. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00107-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart MG, Witsell DL, Smith TL, Weaver EM, Yueh B, Hannley MT. Development and validation of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(2):157-163. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, Lund VJ, Browne JP. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34(5):447-454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browne JP, Hopkins C, Slack R, Cano SJ. The Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT): can we make it more clinically meaningful? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(5):736-741. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawthorne G, Osborne RH, Taylor A, Sansoni J. The SF36 Version 2: critical analyses of population weights, scoring algorithms and population norms. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(4):661-673. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9154-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21(2):271-292. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kharroubi SA, Brazier JE, Roberts J, O’Hagan A. Modelling SF-6D health state preference data using a nonparametric Bayesian method. J Health Econ. 2007;26(3):597-612. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kharroubi SA, O’Hagan A, Brazier JE. Estimating utilities from individual health preference data: a nonparametric Bayesian method. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 2005;54(5):879-895. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2005.00511.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brazier J, Roberts J, Tsuchiya A, Busschbach J. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Econ. 2004;13(9):873-884. doi: 10.1002/hec.866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters SJ, Brazier JE. What is the relationship between the minimally important difference and health state utility values? the case of the SF-6D. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawthorne G, Korn S, Richardson J. Population norms for the AQoL derived from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(1):7-16. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan RW. Minimally invasive nasal valve repair: an evaluation using the NOSE scale. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(3):292-295. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindemann J, Tsakiropoulou E, Konstantinidis I, Lindemann K. Normal aging does not deteriorate nose-related quality of life: assessment with “NOSE” and “SNOT-20” questionnaires. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37(3):303-307. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2009.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.André RF, Vuyk HD, Ahmed A, Graamans K, Nolst Trenité GJ. Correlation between subjective and objective evaluation of the nasal airway: a systematic review of the highest level of evidence. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34(6):518-525. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.02042.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soler ZM, Wittenberg E, Schlosser RJ, Mace JC, Smith TL. Health state utility values in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(12):2672-2678. doi: 10.1002/lary.21847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudmik L, Mace J, Soler ZM, Smith TL. Long-term utility outcomes in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):19-23. doi: 10.1002/lary.24135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luk LJ, Steele TO, Mace JC, Soler ZM, Rudmik L, Smith TL. Health utility outcomes in patients undergoing medical management for chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective multiinstitutional study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(11):1018-1027. doi: 10.1002/alr.21588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moayeri F, Hsueh Y-S, Clarke P, Hua X, Dunt D. Health state utility value in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); the challenge of heterogeneity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. COPD. 2016;13(3):380-398. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1092953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasziou P, Alexander J, Beller E, Clarke P; ADVANCE Collaborative Group . Which health-related quality of life score? a comparison of alternative utility measures in patients with type 2 diabetes in the ADVANCE trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyld M, Morton RL, Hayen A, Howard K, Webster AC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. 2012;9(9):e1001307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Graaff B, Neil A, Sanderson K, Yee KC, Palmer AJ. Quality of life utility values for hereditary haemochromatosis in Australia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0431-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad H, Taylor BV, van der Mei I, et al. The impact of multiple sclerosis severity on health state utility values: evidence from Australia. Mult Scler. 2017;23(8):1157-1166. doi: 10.1177/1352458516672014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidlin M, Fritsch K, Matthews F, Thurnheer R, Senn O, Bloch KE. Utility indices in patients with the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2010;79(3):200-208. doi: 10.1159/000222094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slobogean GP, Younger A, Apostle KL, et al. Preference-based quality of life of end-stage ankle arthritis treated with arthroplasty or arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31(7):563-566. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osnes-Ringen H, Kvamme MK, Kristiansen IS, et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses of elective orthopaedic surgical procedures in patients with inflammatory arthropathies. Scand J Rheumatol. 2011;40(2):108-115. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2010.503661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norman R, Church J, van den Berg B, Goodall S. Australian health-related quality of life population norms derived from the SF-6D. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(1):17-23. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazari FAK, Shahin Y, Khan JA, et al. Comparison of use of Short Form-36 domain scores and patient responses for derivation of preference-based SF6D index to calculate quality-adjusted life years in patients with intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;34:164-170. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strand V, Crawford B, Singh J, Choy E, Smolen JS, Khanna D. Use of “spydergrams” to present and interpret SF-36 health-related quality of life data across rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(12):1800-1804. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.115550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II, psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247-263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bharmal M, Thomas J III. Comparing the EQ-5D and the SF-6D descriptive systems to assess their ceiling effects in the US general population. Value Health. 2006;9(4):262-271. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butterworth P, Crosier T. The validity of the SF-36 in an Australian national household survey: demonstrating the applicability of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey to examination of health inequalities. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rowen D, Brazier J, Roberts J. Mapping SF-36 onto the EQ-5D Index: how reliable is the relationship? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonough CM, Grove MR, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Hilibrand AS, Tosteson AN. Comparison of EQ-5D, HUI, and SF-36–derived societal health state values among Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) participants. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(5):1321-1332. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-5743-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCaffrey N, Kaambwa B, Currow DC, Ratcliffe J. Health-related quality of life measured using the EQ-5D-5L: South Australian population norms. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0537-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuller JC, Levesque PA, Lindsay RW. Assessment of the EuroQol 5-dimension questionnaire for detection of clinically significant global health-related quality-of-life improvement following functional septorhinoplasty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(2):95-100. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Remenschneider AK, Scangas G, Meier JC, et al. EQ-5D–derived health utility values in patients undergoing surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(5):1056-1061. doi: 10.1002/lary.25054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]