Key Points

Question

Is topical tazarotene gel, 0.1%, efficacious in the treatment of atrophic postacne scarring?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial using a split-face study design that included 34 matched treatment areas, significant and comparable clinically relevant improvement from baseline in facial atrophic acne scarring was observed at the 6-month follow-up visit for tazarotene and microneedle therapy, the active control.

Meaning

Tazarotene gel, 0.1%, is a novel treatment approach for atrophic postacne scarring, with an efficacy and tolerability comparable to microneedle therapy.

Abstract

Importance

Evidence is robust for the effectiveness of microneedle therapy in the management of postacne atrophic scarring. A home-based topical treatment with an efficacy comparable to microneedling would be a useful addition in the armamentarium of acne scar management.

Objective

To compare the efficacy of topical tazarotene gel, 0.1%, with microneedling therapy in the management of moderate to severe atrophic acne scars.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective, observer-blinded, active-controlled, randomized clinical trial with 6 months of follow-up conducted between June 2, 2017, and February 28, 2018, at a tertiary care hospital in India. Thirty-six patients with grade 2 to 4 facial atrophic postacne scars and without a history of procedural treatment of acne scars within the previous year were recruited. Analyses were conducted using data from the evaluable population.

Interventions

Both halves of each participant’s face were randomized to receive either microneedling or topical tazarotene therapy. Microneedling was conducted on 1 side of the face with a dermaroller having a needle length of 1.5 mm for a total of 4 sessions during the course of 3 months. Participants were instructed to apply topical tazarotene gel, 0.1%, to the other side of the face once every night during this same period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patients were followed up at 3 and 6 months by a blinded observer, and improvements in acne scar severity based on Goodman and Baron quantitative and qualitative scores and a subjective independent dermatologist score (range, 0-10, with higher scores indicating better improvement) were assessed. Patient satisfaction was assessed using a patient global assessment score (ranging from 0 for no response to 10 for maximum improvement) at these follow-up visits.

Results

There were 36 participants (13 men and 23 women; mean [range] age, 23.4 [18-30] years), and the median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of acne was 6 (4-8) years. For the 34 participants included in the complete data analyses, the median (IQR) quantitative score for acne scar severity at the 6-month follow-up visit following treatment with either tazarotene (from a baseline of 8.0 [6.0-9.8] to 5.0 [3.0-6.0]) or microneedling (from a baseline of 7.0 [6.0-10.8] to 4.5 [3.0-6.0]) indicated significant improvement (P < .001) that was comparable for both treatments (median [IQR] change in severity score from baseline, 2.5 [2.0-4.0] vs 3.0 [2.0-4.0]; P = .42). By contrast, median qualitative acne scar scores were the same for both treatment groups at baseline and did not significantly change following either treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

The present clinical trial showed comparable outcomes of both treatments for the overall improvement of quantitative facial acne scar severity.

Level of Evidence

1.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03170596

This randomized active-controlled clinical trial using a split-face design compares the efficacy and tolerability of the at-home application of topical tazarotene gel, 0.1%, and physician-administered microneedle therapy for the treatment of facial atrophic postacne scarring.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a common dermatologic problem encountered by physicians in clinical practice. It is generally seen in adolescents, and in most of these individuals, there is an improvement in acne with age. However, permanent complications of acne, such as scarring and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, cause psychological distress in some patients. Scarring as a sequela of acne occurs in most patients, with approximately 40% of patients with acne developing clinically relevant scarring.1,2 A higher Dermatology Life Quality Index score, hence a lower quality of life, has been observed in patients with postacne scarring compared with a control population.3 Therefore, in addition to controlling active acne, health care professionals should also address postacne scarring.

Microneedling is a common office-based procedure used to manage postacne atrophic scarring. Its clinical usefulness is well established.4,5,6 A series of 3 to 5 treatment sessions at 2- to 4-week intervals typically results in improvement ranging from 50% to 70%.7 The efficacy of microneedling has been compared with other dermatological procedures for postacne scars, such as chemical peeling,8 cryorolling,9 or carbon dioxide laser treatment,10 usually as combination therapies. However, head to head comparative studies with home-based medical management for acne scars are lacking.

Topical retinoids, such as adapalene and tazarotene, increase dermal collagen through their action on fibroblasts.11 The beneficial effects of adapalene in preventing atrophic acne scarring have been established.12 Topical retinoids have also been used successfully for acne scarring.13 A home-based topical treatment with a comparable efficacy to microneedling and that is well tolerated would be a useful addition in the armamentarium of acne scar management. Hence, in the present study, we evaluated the potential usefulness of topical tazarotene in the management of atrophic postacne scarring. Microneedling was selected as the active control because of its proven efficacy for the treatment of atrophic acne scarring.

Methods

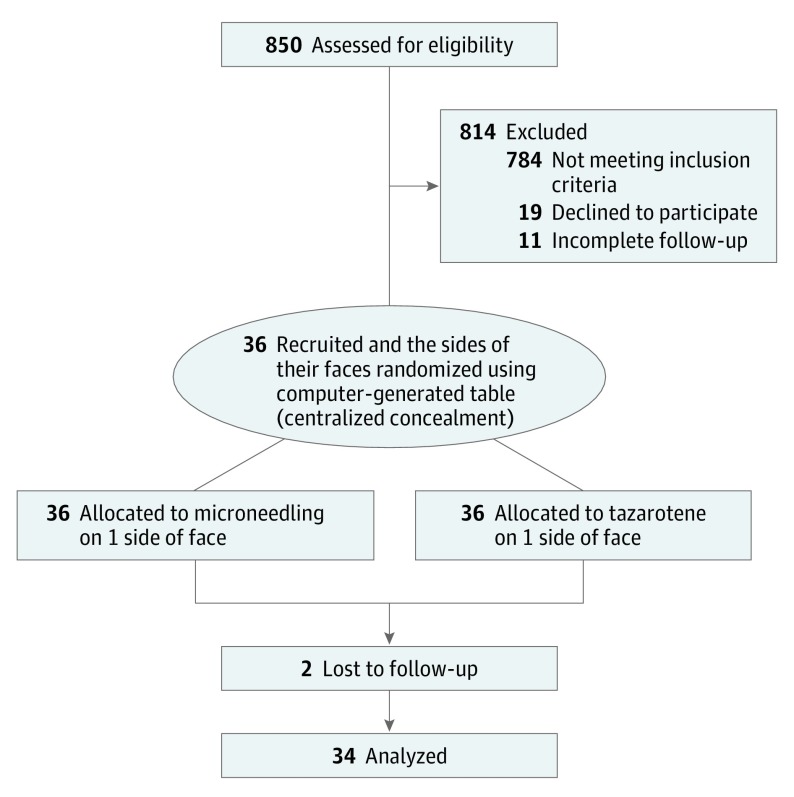

This was a prospective, randomized, active-controlled, observer-blinded pilot study conducted in the dermatology outpatient department clinic of a tertiary care institute in India from June 2, 2017, to February 28, 2018 (trial protocol in Supplement 1). In total, 850 patients with acne attending the general outpatient department of our dermatology department were screened for study inclusion. Of these, 66 patients satisfying inclusion and exclusion criteria were referred to the dermatosurgery clinic. After excluding patients whose ability to participate in the final follow-up owing to geographic or logistic issues was in question and those who were unwilling to participate, 36 patients were included in the study (Figure 1). In the split-face study design used in the present study, 1 side of the face was randomized to receive treatment with either microneedling or topical tazarotene gel, 0.1%. Centralized allocation concealment was conducted. The random number table was generated by one of us (M.R.), and T.N. and S.D. enrolled the participants. Laboratory staff with little knowledge about the study assigned the participants to the interventions based on the randomly generated numbers. The microneedling procedure was performed by T.P.A. and the outcome assessments were conducted by T.N., who was blinded to the intervention. This study was approved by the ethics committee at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India, and follows the Declaration of Helsinki.14 All participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients with grade 2 to grade 4 facial atrophic acne scars as assessed using the Goodman and Baron15 qualitative global scarring grading system and without any surgical or laser treatment of acne scars in the previous 1 year were included. The exclusion criteria included the following: active acne; history of keloidal tendency or hypertrophic scarring; facial scar due to reasons other than acne; collagen vascular disease or bleeding disorder; any active facial infection; pregnant or lactating women; known hypersensitivity to tazarotene; younger than 18 years old; receipt of anticoagulant therapy or aspirin.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change from baseline in acne scar severity grade at the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits. The secondary outcomes were patient satisfaction as assessed using a patient global assessment (PGA) score and adverse events.

Patient Assessment

During the participant’s first visit, baseline demographic characteristics, medical history, and examination findings were recorded, and baseline photographs were captured. Dermatologic examinations to assess skin type, predominant scar type (ice pick, boxcar, or rolling), and the scar severity assessed according to the Goodman and Baron15,16 qualitative and quantitative acne scarring grading systems were performed (by T.N.) for every patient.

Qualitative and Quantitative Acne Scarring Grading Systems

For qualitative grading, macular pigmented scars were given a grade of 1, and mild atrophic scars not visible at social distances of 50 cm or more were given a grade of 2.15 Moderate scars visible at social distances were graded 3, and scars that could not be flattened by manually stretching the skin were attributed a grade of 4.

The quantitative grading system considers both type and number of the scars.16 According to this system, lower numbers were assigned to macular and mild atrophic scars (1) than to moderate (2) or severe (3) atrophic scars or to hyperplastic (4) scars. The numerical value thus obtained was then multiplied by a factor based on the number of each type of lesion, where the multiplier for 1 to 10 scars was 1, for 11 to 20 scars it was 2, and for more than 20 scars it was 3.

Treatment Protocols

The treatment for protocol A consisted of 4 sessions of microneedling at monthly intervals (0, 1, 2, and 3 months). The treatment for protocol B consisted of the application of tazarotene gel, 0.1%, once nightly throughout the entire study period of 3 months.

Microneedling

Microneedling treatment was performed with a standard dermaroller (192 needles with a length of 1.5 mm) by the same investigator (T.P.A.) once per month for 4 months. A topical anesthetic mixture of lignocaine and prilocaine was applied over the face in a thick layer under occlusion 1 hour before the procedure. Microneedling was performed by rolling the dermaroller with uniform and firm pressure in 4 different directions (ie, perpendicular and diagonal to each other) with a to-and-fro motion up to 8 times (a total of 32 passes) or until the end point of uniform pinpoint bleeding was achieved. After treatment, the area was wetted with saline pads. The participants were instructed to follow strict photoprotective measures, including the application of a broad-spectrum sunscreen with sun protection factor 30 over the entire face.

Topical Tazarotene Gel, 0.1%

Patients were instructed to apply a thin film of tazarotene gel, 0.1%, over the affected area once daily in the evening by placing a pea-sized amount of gel in the palm of the hand and using the tip of a finger to cover the entire half of the face. Patients who experienced facial dryness were allowed to use a moisturizing cream during the day (entire face), but the use of any other medication on the face was prohibited.

Follow-up

All patients were followed up at monthly intervals for 3 months and then on the sixth month from the baseline visit. Digital photographs were captured during the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits. Any adverse event experienced by a patient was noted separately for each side of the face at each follow-up visit. In addition, the tolerability of the medication was evaluated by assessing erythema, burning, peeling, and dryness.

Severity scoring with the Goodman and Baron qualitative and quantitative acne scarring grading systems was performed at the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits (by T.N.). An improvement by 2 qualitative grades was considered excellent, by 1 grade was rated good, and by 0 grade was labeled a poor response. Clinical photographs of the patients captured during the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits were reviewed at the end of the study and compared with the baseline images by a blinded, independent dermatologist (T.N.) for clinical improvement and scored on a scale of 0 (no improvement) to 10 (maximum improvement). Response scores were designated poor (0-3), good (4-7), and excellent (8-10).17 Self-assessment was performed by the patients using PGA scores ranging from 0 (no response) to 10 (maximum improvement) during the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits. Scores of 0 to 3 were considered unsatisfactory, 4 to 7 satisfactory, and 8 to 10 highly satisfactory. Hence, both objective and subjective evaluation of the results were conducted.

Photographic Evaluation

Both sides of the face were photographed using a 16.1 megapixels digital camera at the baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-up visits. Digital photographs were taken under consistent background, position, and lighting conditions. The images were captured at distances of 50 and 10 cm from the face.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was estimated based on previous studies on microneedling. The sample size for the present study was 32 patients at 80% power and 95% CI. To take into account possible dropouts, we included 36 patients. Data analysis was conducted on the evaluable population. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc). Discrete categorical data are presented as the number and percentage; continuous data are presented either as the mean and SD or the median and interquartile range, as required. The normality of the quantitative data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For time-related variables of scores or for comparison of the scores from the 2 face sides, Wilcoxon signed rank tests or McNemar tests were applied. Categorical data comparisons were evaluated using Pearson χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and α = .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 36 patients recruited for the present study, 34 patients completed the final follow-up and were included in the final data analysis. Study participants’ clinicodemographic information is given in Table 1. All patients had qualitative grade 3 or 4 acne scars at the initial baseline visit. Neither the quantitative nor the qualitative scar assessment showed significant differences in the baseline acne scar severity between treatment groups.

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Features of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 23.4 (2.9) |

| Age (range), y | 18-30 |

| Male to female ratio, No. | 13:23 |

| Duration of acne, median (IQR), y | 6 (4-8) |

| Race/ethnicity | South Asian/Indo-European linguistic group |

| Skin phototype, No. (%) | |

| III | 4 (11.1) |

| IV | 29 (80.6) |

| V | 3 (8.3) |

| Previous exposure to oral isotretinoin, No. (%) | 12 (33.3) |

| Predominant scar type, No. (%) | |

| Rolling | 20 (55.6) |

| Boxcar | 6 (16.7) |

| Icepick | 5 (13.9) |

| Mixed | 5 (13.9) |

| Quantitative scar severity, median (IQR) | |

| Microneedle group | 7.0 (6.0-10.8) |

| Tazarotene group | 8.0 (6.0-9.8) |

| P value | .47a |

| Qualitative scar severity, median (IQR) | |

| Microneedle group | 4.0 (4.0-4.0) |

| Tazarotene group | 4.0 (4.0-4.0) |

| P value | .99a |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Estimated median difference of 0.0 (95% CI, 0.0-0.0).

Acne Scar Severity Changes Within and Between Treatment Groups

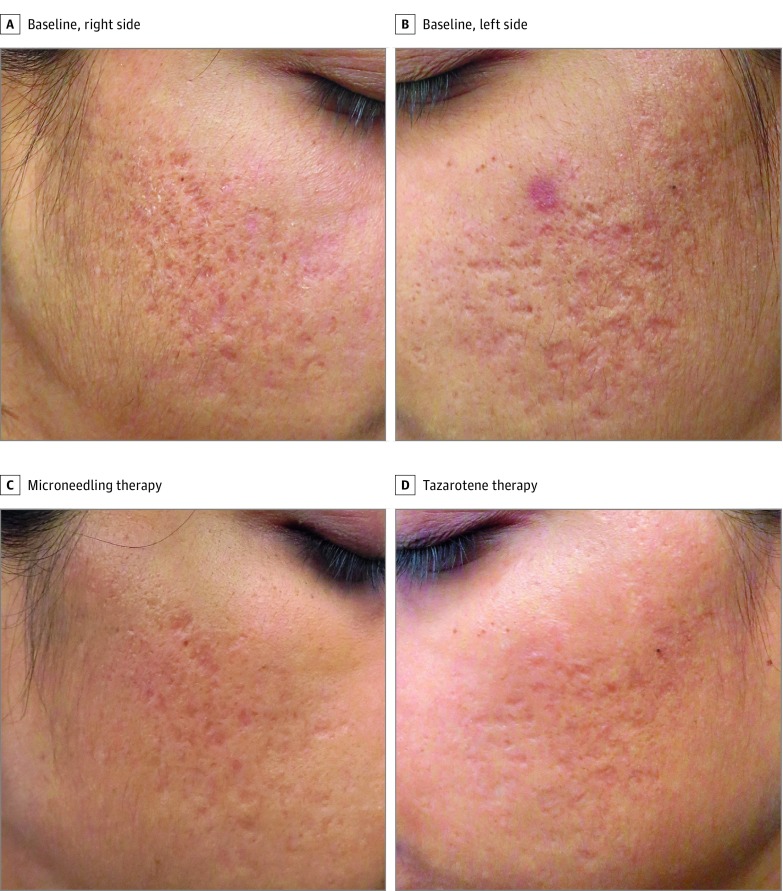

Both treatment protocols significantly improved the quantitative acne scar severity score from baseline (Table 2). An overall improvement in the score from the baseline visit to the final visit (sixth month) was observed for 31 participants (91.2%) in both treatment groups, whereas 3 participants (8.8%) had no improvement from their baseline score (P < .001). When the overall difference in the improvement from the baseline visit to the final visit between the 2 treatment groups was analyzed, 10 participants (29.4%) had better improvement on the microneedling side, 6 participants (17.6%) had better improvement on the tazarotene side (P = .40), and 18 participants (52.9%) had similar improvement on both sides of the face (eg, see the patient shown in Figure 2).

Table 2. Quantitative Acne Scar Severity Scores at Baseline and Follow-up.

| Parameter Assessed | Treatment Group, Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Microneedle | Tazarotene | |

| Quantitative severity score | ||

| Baseline | 7.0 (6.0-10.8) | 8.0 (6.0-9.8) |

| At 3 mo | 5.0 (3.0-9.8) | 5.0 (4.0-8.8) |

| At 6 moa | 4.5 (3.0-6.0) | 5.0 (3.0-6.0) |

| Change in severity score | ||

| From baseline to 3 mob | 2.0 (0.8-3.0) | 1.8 (2.0-3.0) |

| P value | <.001c | <.001d |

| From baseline to 6 moe | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | 2.5 (2.0-4.0) |

| P value | .001f | .001g |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Data analyzed for 34 patients because 2 patients were lost to follow-up at the final visit.

Estimated median difference of 0.0 (95% CI, 0.0-0.5) (P = .38).

Estimated median difference of −2.0 (95% CI, −2.5 to −1.5).

Estimated median difference of −2.0 (95% CI, −2.5 to −1.5).

Estimated median difference of 0.0 (95% CI, −1.0 to 0.0) (P = .42).

Estimated median difference of −3.0 (95% CI, −4.0 to −2.5).

Estimated median difference of −3.0 (95% CI, −3.5 to −2.0).

Figure 2. Quantitative and Qualitative Acne Scar Severity Scores With Microneedling or Tazarotene Therapy.

Both the right (A) and left (B) sides of this patient’s face at baseline have a quantitative score of 4 and qualitative score of 3. At the 6-month follow-up, the quantitative scores for both the microneedle-treated (C) and the tazarotene-treated (D) sides improve by 2, and both the qualitative scores improve by 1, indicating good improvement.

Improvement in the qualitative acne scar severity is given in Table 3. The changes in the qualitative acne scores from the baseline visit were not significant within nor between the treatment groups for the entire study period.

Table 3. Qualitative Acne Scar Severity Scores at Baseline and Follow-up.

| Measure Assessed | No. of Patients in Treatment Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microneedle (n = 36) | Tazarotene (n = 36) | ||

| Qualitative Scar Grade, No. | |||

| Baseline | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 7 | 7 | |

| 4 | 29 | 29 | |

| At 3 mo | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | .91 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | |

| 3 | 9 | 8 | |

| 4 | 22 | 24 | |

| At 6 moa | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | .69 |

| 2 | 8 | 5 | |

| 3 | 10 | 8 | |

| 4 | 15 | 20 | |

| Improvement from baseline, No. (%)b | .41c | ||

| Excellent | 5 (14.7) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Good | 12 (35.3) | 8 (23.5) | |

| Poor | 17 (50.0) | 23 (67.6) | |

| Change in score | |||

| From baseline to 3 mo, P value | .29 | .60 | |

| From baseline to 6 mo, P value | .10 | .54 | |

Data analyzed with 34 because 2 patients were lost to follow-up at the final visit.

Excellent, indicates a change in score of 2; good, a change in score of 1; and poor, no change in score.

Poor improvement vs good to excellent improvement P = .14.

A significant difference was observed in the comparison of the PGA scores (maximum of 10) of both treatment groups at the 3-month follow-up (mean [SD] microneedling, 5.96 [1.96] vs tazarotene, 2.14 [0.59]; mean difference, −3.82; 95% CI, −4.32 to −3.32; P < .001) and 6-month follow-up (mean [SD] microneedling, 5.86 [2.77] vs tazarotene, 5.76 [2.23]; mean difference, −0.97; 95% CI, −1.67 to −0.27; P < .001). The independent dermatologist scores did not show a significant difference between the treatment groups at the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits (median [interquartile range], 5.5 [2.0-7.0] vs 4.5 [2.2-7.0]; estimated median difference assessed with the Hodges-Lehmann-Sen statistic, 0.0; 95% CI, −1.0 to 0.5; P = .67).

Factors Associated With Improvement in the Severity of Acne Scar

We assessed the results with respect to patient characteristics (age, sex, and skin phototype), acne scar characteristics (predominant scar type and duration of disease), and previous treatments obtained (oral isotretinoin for acne or topical retinoids for acne scars). Only previous isotretinoin exposure was correlated with the outcome measure of improvement in acne scarring scores. Those participants previously exposed to isotretinoin were more satisfied with the individual treatment modality even though no difference was observed for the quantitative or qualitative score (eTable in Supplement 2).

Complications

There were no serious complications reported for either treatment method throughout the study period. All patients had procedural pain and erythema following microneedling. Erythema lasting for more than 24 hours was observed in 7 participants (19.4%) after microneedling, and 2 patients had postinflammatory hyperpigmentation on the microneedling side. Tazarotene caused dryness in 13 patients (36.1%) and scaling in 8 patients (22.2%). None of these adverse effects were substantial enough to discontinue the medication. These adverse effects were observed during the initiation of tazarotene therapy and were successfully managed with topical emollients. Breakthrough acne was observed in 3 patients (8.3%) and was managed with combined benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin topical cream.

Discussion

The present clinical trial found a significant amelioration of acne scarring severity with both microneedle and tazarotene gel, 0.1%, therapy. Similar percentages of patients (91.2%) in both groups had an overall improvement from baseline to final visit of their quantitative acne scar severity scores (P < .001); hence, both microneedling and application of tazarotene were found to be effective therapeutic options. The quantitative acne scar severity score on the microneedling side of the face improved by 3.0 (2.0-4.0), and the improvement of this score on the side of the face receiving tazarotene was 2.5 (2.0-4.0), indicating that both methods resulted in a comparable improvement in the quantitative acne severity (between group comparison, P = .42). The mean (SD) PGA score was slightly but significantly superior for the microneedling treatment compared with that for tazarotene application (5.86 [2.77] vs 5.76 [2.23], P < .001). The median (interquartile range) independent dermatologist score was also comparable for both methods (microneedling, 5.5 [2.0-7.0] vs tazarotene 4.5 [2.2-7.0], P = .67). However, the qualitative acne scar severity score did not significantly improve with either treatment.

The US Food and Drug Administration approved tazarotene, a third-generation topical acetylenic retinoid, for acne vulgaris in June 1997.18 Topical tazarotene as a 0.1% gel, 0.1% cream, or 0.1% foam is therapeutically effective.19,20,21 A previous study has established the superior efficacy of tazarotene gel, 0.1%, over adapalene, 0.1%, in the management of acne.22 Tazarotene cream, 0.1%, has been found to significantly improve macular acne scars compared with adapalene gel, 0.3%.23 The present study showed that tazarotene gel, 0.1%, was also effective for the treatment of atrophic acne scarring, with an efficacy comparable to that of microneedling.

We found a significant correlation between previous exposure to oral isotretinoin and patient satisfaction. Retinoids decrease collagenase, which can lead to an accumulation of collagen in scar tissue.24 A recent systematic review documenting the safety of minor dermatologic surgical procedures following recent use of isotretinoin advocates for early intervention of acne scars.25 Patients in the present study with a history of isotretinoin treatment had better PGA scores at 3 months of microneedling or tazarotene therapy than those who had no previous exposure to isotretinoin; but at 6 months, only patients in the tazarotene group had superior PGA scores. Although collagen accumulation has been considered a drawback of isotretinoin therapy owing to the development of hypertrophic scars, the better atrophic acne scar outcomes observed for both the present treatment groups in patients with a history of isotretinoin treatment indicates that the collagen accumulation in this case may actually be beneficial. Collagen induction starts some weeks after microneedling therapy.7,26 Therefore, better collagen induction after 3 months of microneedling therapy, even in participants not exposed to isotretinoin, might have masked the beneficial effects of isotretinoin at 6 months.

Tazarotene was well tolerated by the patients throughout the study. Dryness and scaling were reported in less than one-third of the participants. Similar to a previous study that had reported severe cutaneous adverse effects in only approximately 3% of the participants,27 none of the patients in the present study showed severe adverse effects with tazarotene therapy. Adverse effects of microneedling were also minimal and did not warrant treatment discontinuation.

Outcomes of various interventions for atrophic acne scars vary widely between studies. This variability may be attributable to the many different conditions that exist among these studies, including the initial scar severity, protocol and device used for microneedling, use of an adjuvant, number of patients, tools used for scoring, statistical analysis conducted, and duration of follow-up. Thus, a direct comparison of previous studies is not straightforward. However, unlike previous studies, the present study used validated acne scar severity scoring tools (both quantitative and qualitative) as well as patient and physician assessments of scar improvement in the outcome assessments. Previous studies on microneedling therapy have reported improvement in quartile scores, with most of the studies showing an improvement of 50% to 75%.4,6 In our study, subjective scoring by the independent dermatologist showed an improvement of 55% with microneedling therapy and 45% with tazarotene treatment, which was not a clinically relevant or statistically significant difference between the treatment groups. In a study by Fabbrocini et al,28 an improvement from a baseline subjective score of 7.5 to 4.9 (change of score, 2.6) was noted at 10 months of follow-up. Recently, Alam et al29 showed an improvement in the Goodman and Baron quantitative score of 3.4 by 6 months with microneedling therapy; by contrast, the passive control arm showed an improvement in the score of 0.4. Hence, the observed outcome of the microneedling therapy protocol used in our study, which was associated with a change in the score of 3.0, is consistent with the published literature. Moreover, the outcome observed with tazarotene treatment, a change in the Goodman and Baron quantitative score of 2.5, is comparable not only to the outcome in the active arm but also to the microneedling outcomes reported in the literature. Because few studies have investigated the use of topical retinoids for acne scar management, a comparison evaluating the efficacy of tazarotene and other topical retinoids is not feasible.

Moreover, although the evidence for the efficacy of tazarotene application in active acne is robust,21,23,27,30 the evidence for the efficacy of microneedling therapy is based on studies using fractional radiofrequency microneedling devices.31,32 Even though study participants show improvement in acne using these devices, it appears that this type of therapy must be continued to maintain the attained outcome.32 Thus, the use of a modality such as tazarotene that prevents acne flares while addressing acne scarring is a practical addition to clinical practice.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include a short follow-up of 6 months. Because collagen remodeling is a continuous process lasting more than 1 year,26,33 the observed results may be different with longer follow-up. Hence, further studies with longer follow-up are needed to validate the findings of the present study. In addition, the observed results were not substantiated by a histopathologic assessment of the collagen profile.34

Conclusions

We found significant improvement in baseline acne scar severity following treatment with tazarotene that was comparable to the improvement following microneedling therapy, the active control. Adverse effects were minimal with both treatment options. Hence, tazarotene gel, 0.1%, would be a useful alternative to microneedling in the management of atrophic acne scars. Such a home-based medical management option for acne scarring may decrease physician dependence and health care expenditures for patients with postacne scarring.

Trial protocol

eTable. Correlation Between Previous Exposure to Isotretinoin and Patient Satisfaction

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Fife D. Practical evaluation and management of atrophic acne scars: tips for the general dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(8):50-57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan J, Kang S, Leyden J. Prevalence and risk factors of acne scarring among patients consulting dermatologists in the USA. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(2):97-102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi N, Miyachi Y, Kawashima M. Prevalence of scars and “mini-scars”, and their impact on quality of life in Japanese patients with acne. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):690-696. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou A, Cohen B, Haimovic A, Elbuluk N. Microneedling: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(3):321-339. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alster TS, Graham PM. Microneedling: a review and practical guide. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(3):397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen BE, Elbuluk N. Microneedling in skin of color: a review of uses and efficacy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(2):348-355. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dogra S, Yadav S, Sarangal R. Microneedling for acne scars in Asian skin type: an effective low cost treatment modality. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13(3):180-187. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leheta T, El Tawdy A, Abdel Hay R, Farid S. Percutaneous collagen induction versus full-concentration trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(2):207-216. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01854.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gadkari R, Nayak C. A split-face comparative study to evaluate efficacy of combined subcision and dermaroller against combined subcision and cryoroller in treatment of acne scars. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13(1):38-43. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammed G. Randomized clinical trial of CO2 laser pinpoint irradiation technique with/without needling for ice pick acne scars. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15(3):177-182. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2013.793584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher GJ, Datta S, Wang Z, et al. c-Jun–dependent inhibition of cutaneous procollagen transcription following ultraviolet irradiation is reversed by all-trans retinoic acid. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(5):663-670. doi: 10.1172/JCI9362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreno B, Tan J, Rivier M, Martel P, Bissonnette R. Adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel reduces the risk of atrophic scar formation in moderate inflammatory acne: a split-face randomized controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(4):737-742. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loss MJ, Leung S, Chien A, Kerrouche N, Fischer AH, Kang S. Adapalene 0.3% gel shows efficacy for the treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2018;8(2):245-257. doi: 10.1007/s13555-018-0231-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(12):1458-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring—a quantitative global scarring grading system. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5(1):48-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2006.00222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asif M, Kanodia S, Singh K. Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling verses microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a concurrent split-face study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15(4):434-443. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster RH, Brogden RN, Benfield P. Tazarotene. Drugs. 1998;55(5):705-711. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855050-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shalita AR, Chalker DK, Griffith RF, et al. Tazarotene gel is safe and effective in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 1999;63(6):349-354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shalita AR, Berson DS, Thiboutot DM, et al. ; Tazarotene Cream in Acne Clinical Study Investigator Group . Effects of tazarotene 0.1 % cream in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: pooled results from two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group trials. Clin Ther. 2004;26(11):1865-1873. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JA, Narahari S, Hill D, Feldman SR. Tazarotene foam, 0.1%, for the treatment of acne. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(1):99-103. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2016.1117605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webster GF, Guenther L, Poulin YP, Solomon BA, Loven K, Lee J. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized comparison study of the efficacy and tolerability of once-daily tazarotene 0.1% gel and adapalene 0.1% gel for the treatment of facial acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2002;69(2)(suppl):4-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanghetti E, Dhawan S, Green L, et al. Randomized comparison of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.3% gel in the treatment of patients with at least moderate facial acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(5):549-558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hein R, Mensing H, Müller PK, Braun-Falco O, Krieg T. Effect of vitamin A and its derivatives on collagen production and chemotactic response of fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111(1):37-44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spring LK, Krakowski AC, Alam M, et al. Isotretinoin and timing of procedural interventions: a systematic review with consensus recommendations. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):802-809. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabbrocini G, Fardella N, Monfrecola A. Needling In: Tosti A, De Padova MP, Beer K, eds. Acne Scars: Classification and Treatment. CRC Press; 2009:57-66. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman SR, Werner CP, Alió Saenz AB. The efficacy and tolerability of tazarotene foam, 0.1%, in the treatment of acne vulgaris in 2 multicenter, randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(4):438-446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Combined use of skin needling and platelet-rich plasma in acne scarring treatment. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24(4):177-183. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alam M, Han S, Pongprutthipan M, et al. Efficacy of a needling device for the treatment of acne scars: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(8):844-849. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bershad S, Kranjac Singer G, Parente JE, et al. Successful treatment of acne vulgaris using a new method: results of a randomized vehicle-controlled trial of short-contact therapy with 0.1% tazarotene gel. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):481-489. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.4.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim ST, Lee KH, Sim HJ, Suh KS, Jang MS. Treatment of acne vulgaris with fractional radiofrequency microneedling. J Dermatol. 2014;41(7):586-591. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee KR, Lee EG, Lee HJ, Yoon MS. Assessment of treatment efficacy and sebosuppressive effect of fractional radiofrequency microneedle on acne vulgaris. Lasers Surg Med. 2013;45(10):639-647. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liebl H, Kloth LC. Skin cell proliferation stimulated by microneedles. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2012;4(1):2-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jccw.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Min S, Park SY, Moon J, Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Suh DH. Comparison between Er:YAG laser and bipolar radiofrequency combined with infrared diode laser for the treatment of acne scars: differential expression of fibrogenetic biomolecules may be associated with differences in efficacy between ablative and non-ablative laser treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(4):341-347. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable. Correlation Between Previous Exposure to Isotretinoin and Patient Satisfaction

Data Sharing Statement