Key Points

Question

Do infections increase the risk of subsequent mental disorders during childhood and adolescence?

Findings

This nationwide register-based cohort study that included 1 098 930 individuals born in Denmark between 1995 and 2012 found that severe infections requiring hospitalizations increased the risk of hospital contacts due to mental disorders by 84% and the risk of psychotropic medication use by 42%. Less severe infection treated with anti-infective agents increased the risks by 40% and 22%, respectively; the risks differed among specific mental disorders.

Meaning

These findings may be explained by consequences of infections on the developing brain and by other confounding factors, such as genetics or socioeconomic factors.

This nationwide register-based cohort study investigates the association between all treated infections since birth and the subsequent risk of development of any treated mental disorder during childhood and adolescence in Denmark.

Abstract

Importance

Infections have been associated with increased risks for mental disorders, such as schizophrenia and depression. However, the association between all infections requiring treatment and the wide range of mental disorders is unknown to date.

Objective

To investigate the association between all treated infections since birth and the subsequent risk of development of any treated mental disorder during childhood and adolescence.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population-based cohort study using Danish nationwide registers. Participants were all individuals born in Denmark between January 1, 1995, and June 30, 2012 (N = 1 098 930). Dates of analysis were November 2017 to February 2018.

Exposures

All treated infections were identified in a time-varying manner from birth until June 30, 2013, including severe infections requiring hospitalizations and less severe infection treated with anti-infective agents in the primary care sector.

Main Outcomes and Measures

This study identified all mental disorders diagnosed in a hospital setting and any redeemed prescription for psychotropic medication. Cox proportional hazards regression was performed reporting hazard rate ratios (HRRs), including 95% CIs, adjusted for age, sex, somatic comorbidity, parental education, and parental mental disorders.

Results

A total of 1 098 930 individuals (51.3% male) were followed up for 9 620 807.7 person-years until a mean (SD) age of 9.76 (4.91) years. Infections requiring hospitalizations were associated with subsequent increased risk of having a diagnosis of any mental disorder (n = 42 462) by an HRR of 1.84 (95% CI, 1.69-1.99) and with increased risk of redeeming a prescription for psychotropic medication (n = 56 847) by an HRR of 1.42 (95% CI, 1.37-1.46). Infection treated with anti-infective agents was associated with increased risk of having a diagnosis of any mental disorder (HRR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.29-1.51) and with increased risk of redeeming a prescription for psychotropic medication (HRR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.18-1.26). Antibiotic use was associated with particularly increased risk estimates. The risk of mental disorders after infections increased in a dose-response association and with the temporal proximity of the last infection. In particular, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, personality and behavior disorders, mental retardation, autistic spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, and tic disorders were associated with the highest risks after infections.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although the results cannot prove causality, these findings provide evidence for the involvement of infections and the immune system in the etiology of a wide range of mental disorders in children and adolescents.

Introduction

Previous studies1,2,3 of adults have indicated that severe infections are associated with an increased risk of mental disorders. Potential mechanisms include direct influences of infections in the central nervous system, immune activation, and inflammatory mediators,4,5 as well as alterations in the microbiome.6 A possible role for infection and inflammation in the pathogenesis of severe mental disorders is also supported by genetic studies7,8,9 documenting an increased risk associated with immune-regulatory genes.

However, prior longitudinal studies have been based largely on infections requiring hospitalizations and thus reflect risk associated with the most severe infections. Because most childhood infections are treated on an outpatient basis, the possible role of such infections as risk factors for subsequent mental disorders remains an important question. Some studies5,10,11 have indicated that even less severe infections are associated with increased risks for schizophrenia and depression, but these studies had no lifelong information and did not assess all treated infections. Finally, no study to date has investigated the wide range of mental disorders in childhood and adolescence.

The present study aimed to investigate the association between all types of treated infections, defined by hospital contacts for infections and primary and secondary health care prescriptions of all anti-infective agents, and the risk of any treated mental disorder, defined by hospital contacts due to mental disorders and primary and secondary health care prescription for psychotropic drugs. Therefore, we expand previous findings on schizophrenia and affective disorders1,2,12 to explore all types and severities of infections, to include all mental disorders, and to investigate a large study population with information on both exposures and outcome since birth.

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a nationwide register-based cohort study within the entire Danish population (approximately 5.5 million inhabitants) using the Danish Civil Registration System.13 Information on age, sex, and parents is provided for each resident in Denmark, and the personal identification number enables complete linkage between different registers. For the present study, we identified all individuals born in Denmark between January 1, 1995, and June 30, 2012. Dates of analysis were November 2017 to February 2018. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Danish National Board of Health and was performed using anonymized data, necessitating no informed consent.

Assessment of Infections

Since 1977, the Danish National Patient Registry has registered all contacts to somatic hospitals,14 and we identified all hospitalizations for infections since January 1, 1995 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The Danish National Prescription Registry15 contains detailed information from all Danish pharmacies on each redeemed prescription since 1995. We identified all redeemed prescriptions for anti-infective agents since January 1, 1995 (eTable 2 in the Supplement), subdivided according to antibacterial, antiviral, antimycotic, and antiparasitic agents. The most frequently used antibiotic agents within our setting were further subdivided into broad-spectrum, moderate-spectrum, narrow-spectrum, and topical antibiotics (eTable 3 in the Supplement).12 All infections were identified in a time-varying manner for each individual, and individuals could have been exposed to several different anti-infective agents.

We expected the majority to have redeemed anti-infective agent prescriptions.12,16 Therefore, we chose a control group to include individuals who redeemed no prescription for anti-infective agents or who only redeemed prescriptions for penicillin G (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] code J01CE01) and/or antibiotics for topical use (ATC code D06A) because these agents have minimal consequences on the gut microbiome. Individuals were grouped as having redeemed 0 prescriptions until the date of the first prescription for anti-infective agents defined as exposure agents.

Assessment of Mental Disorders

First, we included information from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register17 on all psychiatric inpatient and outpatient contacts since 1995, coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) since 1994. We identified all of the below-mentioned disorders (with ICD-10 codes) diagnosed in an inpatient or outpatient setting before July 1, 2013. (1) The first diagnosis of a mental disorder within F20 to F99. We did not include organic mental disorders (F00-F09) because the present study population was very young. Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance abuse (F10-F19) were not included because an increased rate of infections before an F10 to F19 diagnosis may reflect more infections due to drug abuse. Furthermore, we identified the first diagnosis within the following specific categories: (2) schizophrenia spectrum disorders (F20-F29); (3) affective disorders (F30-F39); (4) neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40-F49); (5) behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F50-F59); (6) adult personality and behavior disorders (F60-F69); (7) mental retardation (F70-F79); (8) disorders of psychological development (F80-F89); and (9) behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (F90-F99). Finally, we identified the following specific diagnoses, representing those mental disorders most often diagnosed during childhood and adolescence18: (10) obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (F42.x), (11) eating disorder (F50.x), (12) autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) (F84.x, excluding F84.2-F84.4), (13) attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (F90.x and F98.8), (14) oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder (ODD/CD) (F90.1 and F91.x), (15) attachment disorders (F94.x, excluding F94.0), and (16) tic disorders (F95.x).

We included the first-time diagnosis when investigating category (1) (any mental disorder). Regarding the specific diagnoses, we were interested in the first diagnosis for each specific diagnosis, irrespective of other previous psychiatric diagnoses or previous psychotropic drug use.

Second, we used the Danish National Prescription Registry15 to identify the first redeemed prescription of the following psychotropic medications redeemed before July 1, 2013 (with ATC codes): antipsychotics (N05A), anxiolytics (N05B), antidepressants (N06A), ADHD medications (N06B), and drugs against dependence (N07B).

Follow-up

We followed up all individuals from their first birthday (the exposure was measured since birth, as done in a previous register-based study18). Follow-up continued until the occurrence of an outcome, death, emigration, or end of the study period on June 30, 2013, whichever occurred first.

Statistical Analysis

We performed Cox proportional hazards regression analyses using age as the underlying timescale (ie, we compared individuals of the same age) and report hazard rate ratios (HRRs), including 95% CIs. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index,19 highest parental educational level,20 and any parental mental disorder since 1969 (ICD-8 codes 290-315 and ICD-10 codes F00-F99).17 The parental covariates were identified in a time-varying manner: a child contributed risk time for the group with no mental disorders until the date when 1 of the parents was diagnosed as having a mental disorder, and from this date the child was categorized as having either a father or mother with a mental disorder. Analyses were mutually adjusted for the other infections (eg, analyses on anti-infective agents were adjusted for hospitalizations).

The primary analyses compared (1) individuals with hospitalization for infection vs individuals without hospitalization for infection and (2) individuals with 1 or more redeemed anti-infective agent prescription vs individuals with 0 redeemed anti-infective agent prescriptions. In both analyses, we investigated (1) the risk of hospitalization for any mental disorder and (2) the risk of redeeming a prescription for any psychotropic medication. In secondary analyses on the consequences of treatment with anti-infective agents, we applied different reference groups to explore whether a potentially higher risk may have been due to the small reference group that included only individuals with 0 prescriptions. For these additional analyses, we performed analyses using individuals with 0 to 1 prescriptions, 0 to 2 prescriptions, and 0 to 3 prescriptions as the reference groups. Finally, we explored the risk of specific mental disorders. Individuals diagnosed as having several mental disorders were counted as cases in each of the specific outcome categories.

To explore whether a potential consequence of anti-infective agents could be due to severe infections resulting in hospitalizations, we calculated the risks for all of the above-mentioned outcomes among individuals exposed to anti-infective agents, applying hospitalization for infection as a time-dependent variable. Furthermore, we explored the risk pattern depending on (1) the number of hospitalizations and anti-infective agents; (2) the presumed infectious agent leading to hospitalization (ie, bacterial, viral, or other), the specific anti-infective agents (ie, antibiotics, antivirals, antimycotics, or antiparasitics), and the number of redeemed prescriptions for different types of anti-infectious agents; and (3) the time to outcome since the last hospitalization or redeemed prescription. Moreover, we investigated the risks associated with infections during specific ages. Due to the number of analyses performed, we reduced the 2-sided significance level by dividing by the number of performed tests to correct for multiple testing. The Cox proportional hazards regression assumptions were tested based on Schoenfeld residuals and were not violated in any analysis. The Wald test was used to assess linear associations.

Because the association between infections and mental disorders may be due to genetic factors, we performed sibling analyses. For this process, we excluded individuals without siblings born during our study period and performed the above-mentioned analyses stratified by siblings. Finally, to use a completely untreated reference group, we performed analyses without those individuals who only redeemed prescriptions for the control antibiotics (ie, ATC codes J01CE01 and D06A).

Results

We identified 1 098 930 individuals (51.3% male; mean [SD] age at the end of follow-up, 9.76 [4.91] years; range, 1-18 years) born in Denmark between January 1, 1995, and June 30, 2012 (eTable 4 in the Supplement) and followed up for 9 620 807.7 person-years (incidence rates are listed in eTable 5 in the Supplement). A total of 42 462 individuals (3.9%) (66.4% male; mean age, 9.5 years at first diagnosis) had a hospitalization for any mental disorder, and 56 847 individuals (5.2%) (60.1% male; mean age, 6.3 years at first prescription) redeemed a prescription for any psychotropic medication.

Infections and the Risk of Any Treated Mental Disorder

Individuals requiring hospitalization for infection had an increased HRR of 1.84 (95% CI, 1.69-1.99) for having a hospitalization for any mental disorder and an HRR of 1.42 (95% CI, 1.37-1.46) for redeeming a prescription for any psychotropic medication (Table 1). Infection treated with anti-infective agents was associated with HRRs of 1.40 (95% CI, 1.29-1.51) and 1.22 (95% CI, 1.18-1.26), respectively. Individuals treated for infections with anti-infective agents who were not hospitalized for infections during follow-up still had an increased risk of being diagnosed as having a mental disorder (HRR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.25-1.44) and for being treated with psychotropic medication (HRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.16-1.24). Antibiotics were the anti-infective agents associated with the largest risk increase in mental disorders (Table 1), whereas antivirals and antimycotics did not increase the risk estimates. The findings regarding anti-infective agents were significant with all reference groups (Table 2). Additional analyses within different age groups (1 to 6 years, >6 to 12 years, and >12 to 18 years) supported the primary findings (eTable 5 and eTable 6 in the Supplement). We found increased risks for mental disorder associated with treated infections within different age groups, but no clear pattern or specifically vulnerable age group emerged (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Risk of Any Treated Mental Disorder Among Persons Born Between 1995 and 2012 in Denmark According to Hospitalization for Infection and Anti-infective Agent Prescription.

| Variable | Hospitalization for Any Mental Disorder | Prescription for Any Psychotropic Medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, No. (%) | HRR (95% CI)a | Cases, No. (%) | HRR (95% CI)a | |

| Total | 42 462 | NA | 56 847 | NA |

| Hospitalization for Infection | ||||

| 0 Hospitalizations for infection [reference] | 29 315 (69.0) | 1 [Reference] | 40 710 (71.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| ≥1 Hospitalization for infection | 13 147 (31.0) | 1.84 (1.69-1.99)b | 16 137 (28.4) | 1.42 (1.37-1.46)b |

| Bacterial | 3434 (8.1) | 1.89 (1.73-2.06)b | 4181 (7.4) | 1.45 (1.40-1.51)b |

| Viral | 4430 (10.4) | 1.82 (1.67-1.98)b | 5870 (10.3) | 1.43 (1.39-1.49)b |

| Other | 5629 (13.3) | 1.82 (1.69-1.97)b | 6344 (11.2) | 1.44 (1.39-1.49)b |

| Infection Treated With Anti-infective Agents | ||||

| 0 Anti-infective agent [reference] | 702 (1.7) | 1 [Reference] | 4701 (8.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| ≥1 Anti-infective agent | 41 760 (98.3) | 1.40 (1.29-1.51)b | 52 146 (91.7) | 1.22 (1.18-1.26)b |

| Type of Anti-infective Agentc | ||||

| Antibiotics | 37 462 (88.2) | 1.41 (1.35-1.46)b | 47 145 (83.2) | 1.22 (1.17-1.27)b |

| Broad spectrum | 5650 (13.3) | 1.35 (1.27-1.44)b | 23 622 (41.7) | 1.24 (1.19-1.29)b |

| Moderate spectrum | 25 150 (59.2) | 1.24 (1.16-1.32)b | 26 150 (46.1) | 1.22 (1.18-1.28)b |

| Narrow spectrum | 31 886 (75.1) | 1.24 (1.16-1.33)b | 29 584 (52.2) | 1.21 (1.17-1.25)b |

| Topical | 29 496 (69.4) | 1.22 (1.14-1.30)b | 26 991 (47.6) | 1.21 (1.16-1.26)b |

| Antivirals | 2113 (5.0) | 1.09 (0.64-1.84) | 2128 (3.8) | 0.95 (0.66-1.35) |

| Antimycotics | 9743 (22.9) | 1.14 (0.91-1.42) | 10 062 (17.8) | 1.14 (1.02-1.28) |

| Antiparasitic | 8587 (20.2) | 0.88 (0.70-1.10) | 7951 (14.0) | 0.88 (0.73-1.06) |

Abbreviations: HRR, hazard rate ratio; NA, not applicable.

The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, highest parental educational level, any parental mental disorder since 1969, calendar period, and hospitalization for infection (in the analyses for anti-infective agents). The significance level was set at .05 divided by 26, which equals .0019.

Statistically significant.

The categorization of different types of anti-infective agents is summarized in eTable 2 in the Supplement. The analyses on the different anti-infective agents are mutually adjusted for the other anti-infective agents.

Table 2. Different Reference Groups for the Association Between Infection Treated With Anti-infective Agents and the Risk of Any Treated Mental Disorder Among Persons Born Between 1995 and 2012 in Denmark.

| Variable | Hospitalization for Any Mental Disorder | Prescription for Any Psychotropic Medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, No. (%) | HRR (95% CI)a | Cases, No. (%) | HRR (95% CI)a | |

| Total | 42 462 | NA | 56 847 | NA |

| Reference Group 1 With 0 Anti-infective Agents | ||||

| No. of anti-infective agents | ||||

| 0 [Reference] | 702 (1.7) | 1 [Reference] | 4701 (8.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 2783 (6.6) | 1.06 (0.97-1.16) | 4063 (7.1) | 1.19 (1.14-1.24)b |

| 2 | 2938 (6.9) | 1.14 (1.05-1.24)b | 6729 (11.8) | 1.13 (1.07-1.17)b |

| 3 | 2777 (6.5) | 1.22 (1.12-1.32)b | 5463 (9.6) | 1.20 (1.16-1.25)b |

| 4 | 2513 (5.9) | 1.30 (1.20-1.41)b | 4518 (7.9) | 1.22 (1.16-1.27)b |

| 5-9 | 12 210 (28.8) | 1.45 (1.35-1.57)b | 14 814 (26.1) | 1.28 (1.24-1.33)b |

| 10-19 | 13 272 (31.3) | 1.71 (1.59-1.84)b | 12 104 (21.3) | 1.49 (1.44-1.55)b |

| ≥20 | 5267 (12.4) | 2.04 (1.88-2.21)b | 4455 (7.8) | 1.73 (1.65-1.81)b |

| Reference Group 2 With 0-1 Anti-infective Agents | ||||

| No. of anti-infective agents | ||||

| 0-1 [Reference] | 3485 (8.2) | 1 [Reference] | 8764 (15.4) | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 | 2938 (6.9) | 1.28 (1.17-1.40)b | 6729 (11.8) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) |

| 3 | 2777 (6.5) | 1.30 (1.18-1.43)b | 5463 (9.6) | 1.11 (1.07-1.15)b |

| 4 | 2513 (5.9) | 1.22 (1.11-1.34)b | 4518 (7.9) | 1.12 (1.08-1.16)b |

| 5-9 | 12 210 (28.8) | 1.36 (1.30-1.43)b | 14 814 (26.1) | 1.18 (1.15-1.21)b |

| 10-19 | 13 272 (31.3) | 1.61 (1.54-1.68)b | 12 104 (21.3) | 1.37 (1.33-1.41)b |

| ≥20 | 5267 (12.4) | 1.97 (1.88-2.08)b | 4455 (7.8) | 1.59 (1.52-1.65)b |

| Reference Group 3 With 0-2 Anti-infective Agents | ||||

| No. of anti-infective agents | ||||

| 0-2 [Reference] | 6423 (15.1) | 1 [Reference] | 15 493 (27.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| 3 | 2777 (6.5) | 1.07 (1.02-1.12)b | 5463 (9.6) | 1.09 (1.05-1.12)b |

| 4 | 2513 (5.9) | 1.00 (0.95-1.04) | 4518 (7.9) | 1.10 (1.06-1.14)b |

| 5-9 | 12 210 (28.8) | 1.12 (1.09-1.16)b | 14 814 (26.1) | 1.16 (1.13-1.18)b |

| 10-19 | 13 272 (31.3) | 1.33 (1.29-1.37)b | 12 104 (21.3) | 1.34 (1.31-1.38)b |

| ≥20 | 5267 (12.4) | 1.53 (1.48-1.59)b | 4455 (7.8) | 1.56 (1.50-1.62)b |

| Reference Group 4 With 0-3 Anti-infective Agents | ||||

| No. of anti-infective agents | ||||

| 0-3 [Reference] | 9200 (21.7) | 1 [Reference] | 20 956 (36.9) | 1 [Reference] |

| 4 | 2513 (5.9) | 0.98 (0.93-1.02) | 4518 (7.9) | 1.07 (1.04-1.11)b |

| 5-9 | 12 210 (28.8) | 1.10 (1.07-1.13)b | 14 814 (26.1) | 1.13 (1.10-1.16)b |

| 10-19 | 13 272 (31.3) | 1.30 (1.26-1.34)b | 12 104 (21.3) | 1.31 (1.28-1.34)b |

| ≥20 | 5267 (12.4) | 1.50 (1.45-1.56)b | 4455 (7.8) | 1.52 (1.46-1.57)b |

Abbreviations: HRR, hazard rate ratio; NA, not applicable.

The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, highest parental educational level, any parental mental disorder since 1969, calendar period, and hospitalization for infection. The significance level was set at .05 divided by 14, which equals .0036, for reference group 1 with 0 anti-infective agents; as .05 divided by 12, which equals .0042, for reference group 2 with 0 to 1 anti-infective agents; as .05 divided by 10, which equals .0050, for reference group 3 with 0 to 2 anti-infective agents; and as .05 divided by 8, which equals .0063, for reference group 3 with 0 to 3 anti-infective agents.

Statistically significant.

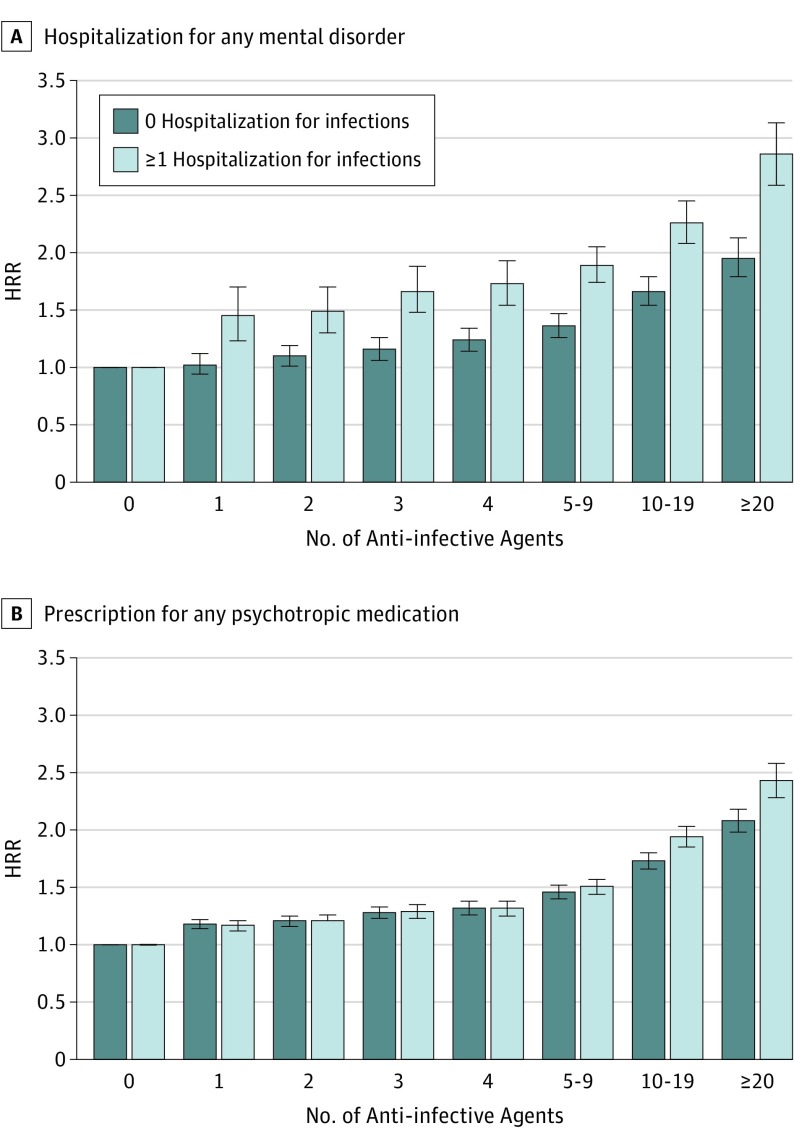

The risk of mental disorders increased in a dose-response association depending on the number of treated infections (Table 2 and the Figure) and the number of different anti-infective agents (eTable 7 in the Supplement), with the risks being most elevated among those with prior hospital contacts due to infections (Figure). Furthermore, the results were associated with time since the last hospitalization for infection, with highest risks immediately after the infection and with risks remaining increased up to 10 years after the last treated infection (Table 3).

Figure. Risk of Hospitalization for Any Mental Disorder and Risk of Prescription for Any Psychotropic Medication.

A and B, Risk is shown for persons born between 1995 and 2012 in Denmark with and without hospitalization for infection who redeemed anti-infective agent prescriptions. HRR indicates hazard rate ratio. The error bars represent 95% CIs. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, parental educational level, and parental mental disorders.

Table 3. Risk of Any Treated Mental Disorder Among Persons Born Between 1995 and 2012 in Denmark According to Time Since the Last Infection.

| Variable | Hospitalization for Any Mental Disorder | Prescription for Any Psychotropic Medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, No. (%) | HRR (95% CI)a | Cases, No. (%) | HRR (95% CI)a | |

| Total | 42 462 | NA | 56 847 | NA |

| Time Since the Last Hospitalization for Infection | ||||

| 0 Hospitalizations for infection | 29 315 (69.0) | 1 [Reference] | 40 710 (71.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| 0 to <3 mo | 202 (0.5) | 5.66 (4.84-6.62)b | 1144 (2.0) | 3.76 (3.50-4.02)b |

| ≥3 to <6 mo | 241 (0.6) | 3.65 (3.15-4.22)b | 1113 (2.0) | 1.95 (1.85-2.03)b |

| ≥6 to <12 mo | 505 (1.2) | 2.00 (1.78-2.23)b | 1459 (2.6) | 1.66 (1.57-1.76)b |

| ≥1 to <2 y | 1217 (2.9) | 1.74 (1.60-1.91)b | 1848 (3.3) | 1.53 (1.47-1.60)b |

| ≥2 to <5 y | 3553 (8.4) | 1.25 (1.17-1.35)b | 3520 (6.2) | 1.36 (1.31-1.41)b |

| ≥5 to <10 y | 4445 (10.5) | 1.07 (1.01-1.16) | 4399 (7.7) | 1.10 (0.99-1.21) |

| ≥10 y | 2138 (5.0) | 0.79 (0.73-0.86)b | 2654 (4.7) | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) |

| Time Since the Last Anti-infective Agentc | ||||

| 0 Anti-infective agents | 702 (1.6) | 1 [Reference] | 4701 (8.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| 0 to <3 mo | 4361 (10.3) | 1.46 (1.38-1.55)b | 11 917 (21.0) | 1.24 (1.21-1.27)b |

| ≥3 to <6 mo | 2413 (5.7) | 1.45 (1.36-1.53)b | 5746 (10.1) | 1.23 (1.19-1.28)b |

| ≥6 to 12 mo | 4508 (10.6) | 1.37 (1.29-1.46)b | 7766 (13.7) | 1.24 (1.20-1.29)b |

| ≥1 to <2 y | 6761 (15.9) | 1.33 (1.25-1.41)b | 8256 (14.5) | 1.21 (1.17-1.26)b |

| ≥2 to <5 y | 12 301 (29.0) | 1.25 (1.18-1.33)b | 10 893 (19.2) | 1.10 (1.05-1.14) |

| ≥5 to <10 y | 6494 (15.3) | 1.17 (1.09-1.26) | 6089 (10.7) | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) |

| ≥10 y | 841 (2.0) | 0.96 (0.79-1.18) | 1479 (2.6) | 1.14 (0.97-1.36) |

Abbreviations: HRR, hazard rate ratio; NA, not applicable.

The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, highest parental educational level, any parental mental disorder since 1969, calendar period, and hospitalization for infection (in the analyses for anti-infective agents). The significance level was set at .05 divided by 28, which equals .0018.

Statistically significant.

The results on time since the last anti-infective agent fitted a dose-response association that was assessed with the Wald test.

Infections and the Risk of Specific Mental Disorders

Table 4 summarizes the associations between treated infections and specific diagnostic categories of mental disorders. A total of 10 537 individuals received more than 1 mental disorder diagnosis. In particular, the risks were increased for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, OCD, personality and behavior disorders, mental retardation, ASD, ADHD, ODD/CD, and tic disorders. The results for anti-infective agents were higher among individuals with prior hospitalizations due to infections and increased in a dose-response association.

Table 4. Risk of Specific Mental Disorders Among Persons Born Between 1995 and 2012 in Denmark Requiring Hospitalization for Infection or Having Infection Treated With Anti-infective Agents.

| Variable | Cases, No. (%) | Hospitalization for Infection, No. (%)a | HRR (95% CI)b | Infection Treated With Anti-infective Agents, No. (%)c | HRR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-10 Diagnosis | |||||

| Any mental disorder (F20-F99) | 42 462 | 13 147 (31.0) | 1.84 (1.69-1.99)d | 41 760 (98.3) | 1.42 (1.37-1.46)d |

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (F20-F29) | 942 | 317 (33.7) | 1.80 (1.29-2.52)d | 876 (93.0) | 1.14 (0.87-1.48) |

| Affective disorders (F30-F39) | 2298 | 763 (33.2) | 1.37 (0.86-2.17) | 2279 (99.2) | 1.18 (0.75-1.87) |

| Anxiety disorders (F40-F49) | 8640 | 2863 (33.1) | 2.06 (1.63-2.60)d | 8558 (99.1) | 1.61 (1.29-2.01)d |

| OCD | 1583 | 500 (31.6) | 2.74 (1.42-5.31)d | 1574 (99.4) | 2.38 (1.23-4.60)d |

| Physiological and physical disturbances (F50-F59) | 1610 | 440 (27.3) | 1.55 (0.88-2.73) | 1596 (99.1) | 1.49 (0.87-2.55) |

| Eating disorder | 1562 | 424 (27.1) | 1.53 (0.83-2.80) | 1550 (99.2) | 1.49 (0.84-2.65) |

| Personality and behavior disorders (F60-F69) | 622 | 243 (39.1) | 2.64 (1.65-4.23)d | 599 (96.3) | 1.87 (1.23-2.84)d |

| Mental retardation (F70-F79) | 2293 | 828 (36.1) | 3.79 (2.55-5.63)d | 2260 (98.6) | 1.90 (1.34-2.69)d |

| Developmental disorders (F80-F89) | 13 791 | 4091 (29.7) | 1.53 (1.36-1.73)d | 13 463 (97.6) | 1.14 (1.02-1.27) |

| ASD | 4078 | 1199 (29.4) | 1.54 (1.27-1.87)d | 3955 (97.0) | 1.11 (0.92-1.33) |

| Behavioral and emotional disorders (F90-F99) | 21 489 | 6758 (31.4) | 2.03 (1.80-2.30)d | 21 174 (98.5) | 1.46 (1.30-1.63)d |

| ADHD | 14 168 | 4527 (32.0) | 2.09 (1.78-2.46)d | 14 000 (98.8) | 1.56 (1.34-1.82)d |

| ODD/CD | 2478 | 863 (34.8) | 3.23 (2.02-5.17)d | 2457 (99.2) | 2.11 (1.37-3.25)d |

| Attachment disorders | 1838 | 582 (31.7) | 1.54 (1.13-2.09) | 1787 (97.2) | 1.11 (0.83-1.49) |

| Tic disorders | 924 | 277 (30.0) | 3.33 (1.37-8.08)d | 919 (99.5) | 3.13 (1.29-7.54)d |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autistic spectrum disorder; HRR, hazard rate ratio; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems, 10th Revision; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ODD/CD, oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder.

The reference group consisted of individuals without hospitalization for infection.

The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, highest parental educational level, any parental mental disorder since 1969, hospitalization for infection (in the analyses for anti-infective agents), and other previous mental disorders. The significance level was set at .05 divided by 30, which equals .0017.

The reference group consisted of individuals with no anti-infective agent.

Statistically significant.

Sensitivity Analysis

A total of 821 346 siblings were included for sibling analyses, of whom 30 785 (3.7%) were hospitalized for any mental disorder and 43 183 (5.3%) were treated with psychotropic medication. Hospitalization for infection was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for any mental disorder (HRR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.16-1.27) and for treatment with psychotropic medication (HRR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.14-1.19) compared with siblings. Anti-infective agents were also associated with increased risks for hospitalization for any mental disorder (HRR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.07-1.26) but not for treatment with psychotropic medication (HRR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.93-1.01). Additional analyses are presented in the eResults in the Supplement.

Discussion

This nationwide register-based cohort study, including all individuals up to age 18 years born in Denmark between 1995 and 2012 (N = 1 098 930), represents the most detailed assessment to date of the association between all treated infections from birth to late adolescence and the subsequent risk of any treated mental disorder during childhood and adolescence. Infections requiring hospitalizations were associated with an approximately 84% increased risk of any mental disorder diagnosed in a hospital setting and an approximately 42% increased risk of use of any psychotropic medication, whereas infection treated with anti-infective agents was associated with increased risks of 40% and 22%, respectively. These risks increased in a dose-response association with the number of infections and the temporal proximity of the last infection and were supported by analyses that included different reference groups and sibling analyses. However, the risk estimates were still significant but attenuated in the sibling analyses, indicating that our findings should be interpreted in light of other important confounding factors, such as genetic, familial, and socioeconomic factors. A detailed assessment showed that the risks differed among specific mental disorders, being most elevated for OCD, mental retardation, and tic disorders.

Infections and Mental Disorders

Prior studies have mostly investigated hospitalization for infection1,2,3,4 (ie, severe infections) and did not have information regarding exposure and outcomes since birth and only included specific severe mental disorders.1,2,3,4,12 Few studies5,12 have suggested that even less severe infections treated in the primary care sector were associated with an increased risk of specific severe mental disorders. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to indicate that any treated infection, including less severe infection, is associated with an increased risk of a wide range of childhood and adolescent mental disorders.

Implications for Pathogenesis

Several pathogenetic mechanisms might explain our findings. First, the infection per se may influence the brain and thus result in an increased risk of mental disorders. Several studies have indicated that infective agents can cross the blood-brain barrier by both active21 and passive22 transport, suggesting that even peripheral infections may alter the central nervous system. This possibility is supported by our findings showing that the risks of mental disorders increased with the amount and severity of the treated infections. Second, it has been suggested that anti-infective agents influence the gut microbiome and result in a disturbed microflora of the gut.6 These disturbances may alter the brain (eg, via the vagus nerve22 or alterations in the blood-brain barrier23) and hence result in an increased risk of mental disorders. Third, genetic studies have indicated associations between mental disorders and genes of the immune system7 and specifically the innate immune system.8,9 Therefore, it is possible that some of our findings are a reflection of an increased genetic susceptibility to infections. However, our results on siblings suggest that infections themselves are contributing to the risk above and beyond genetic susceptibility. Nonetheless, because our study was population based and the sibling analyses attenuated the risk estimates, other confounding factors, such as environmental or familial factors and help-seeking behavior, may at least partly explain our findings.

Strengths and Limitations

The population-based setting and well-validated nationwide registers strengthen our findings.13,14,15,17,19,23,24 The present study is the first to date with the ability to prospectively follow up a nationwide sample with full information since birth regarding exposure (all types of treated infections), outcome (any treated mental disorder), and important covariates (age, sex, somatic comorbidity, and parental education and mental disorders), still representing a relevant study population for the investigated outcomes. Anti-infective agents have been used as a proxy for infections in previous studies investigating the risk of somatic diseases25,26,27 and mental disorders.12 In addition, we performed sibling analyses and applied 4 different reference groups with different exposure degrees to anti-infective agents, all supporting our findings.

Our study had some limitations. First, we only had follow-up to a maximum of age 18 years because the Danish National Prescription Registry has complete coverage since 1995. Hence, we were only able to investigate childhood and adolescent mental disorders with, for example, early onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorders and affective disorders or of adult personality and behavior disorders. This situation may explain why we found no significant associations with affective disorders in contrast to a previous study.2 The long-term risk of mental illness should be interpreted with caution due to the shorter follow-up period herein than in previous studies. Second, antibiotics are often prescribed for nonbacterial infections (eg, viral infections28,29), with overprescription of antibiotics being high but most prominent among adults older than 18 years.29 Nevertheless, anti-infective agents are not prescribed without clinical symptoms of an infection.28,29 Third, a meta-analysis28 indicated that antibiotic compliance is low, with 62.2% completing an antibiotic treatment regimen. Hence, we assumed that all individuals treated with anti-infective agents had an infection, but we could not unequivocally determine what the type of infection was or whether the observed risks were due to the infection or the possible influence of anti-infective agents. Fourth, we were unable to include mental disorders treated nonpharmacologically in the primary care sector and infections not treated pharmacologically or treated with, for example, acetaminophen, which is available over the counter and used for other indications. Fifth, detection bias may have occurred at the time of the infection; however, our findings were still significant several years after the last treated infection, thus minimizing this limitation. Sixth, frequent medication use may be a proxy for factors like social deprivation, parental anxiety, and urbanicity, indicating residual confounding. Nevertheless, we adjusted for important social factors in a time-varying manner, allowing adjustment for changes in these factors during childhood and adolescence. Adjustment for these variables is also a good indicator of the socioeconomic status of a child, and they have been applied in previous studies1,2,12 based on Danish register data. Sixth, sibling analysis can control for shared environmental and genetic confounders; however, estimates might be more severely biased by nonshared confounders and measurement error.30

Conclusions

This study found associations between any treated infection and increased risks of all treated childhood and adolescent mental disorders, with the risks differing among specific mental disorders. These findings might be explained by direct influences of infections, genetics, or disturbances of the microbiome; however, due to the study design, other confounding factors need to be considered when interpreting our results. A better understanding of the role of infections and antimicrobial therapy in the pathogenesis of mental disorders might lead to new methods for the prevention and treatment of these devastating disorders.

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, 8th Edition (ICD-8) and ICD-10 Codes for Site and Type of the Infection Resulting in a Hospitalization

eTable 2. Anti-Infective Agents According to the Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical System (ATC) From the World Health Organization (WHO), Subdivided Into Antibacterial, Antiviral, Antimyotic and Antiparasitic Products

eTable 3. The Most Frequently Used Antibiotics Within the Study Population, According to the Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical System (ATC) From the World Health Organization (WHO), and Subdivided Into Broad-Spectrum, Moderate-Spectrum, Narrow-Spectrum, and Topical Antibiotics

eTable 4. Characteristics of the Study Population (N=1,098,930) at the End of Follow-up

eTable 5. Risk for Any Treated Mental Disorder Among All Individuals Born in Denmark Between 1995 and 2012 According to Hospitalizations With Infections and Prescriptions for Anti-infective Agents

eTable 6. Risk of the Specific Mental Disorders Among Individuals With Infections Treated With Anti-infective Agents or Requiring Hospitalizations

eTable 7. Risk for Any Treated Mental Disorder Among Persons Born Between 1995 and 2012 According to the Amount of Different Groups of Anti-infective Agents

eResults. Supplementary Results

References

- 1.Benros ME, Nielsen PR, Nordentoft M, Eaton WW, Dalton SO, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for schizophrenia: a 30-year population-based register study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1303-1310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, et al. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):812-820. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen PR, Benros ME, Mortensen PB. Hospital contacts with infection and risk of schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study with linkage of Danish national registers. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6):1526-1532. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomström Å, Karlsson H, Svensson A, et al. Hospital admission with infection during childhood and risk for psychotic illness—a population-based cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6):1518-1525. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandaker GM, Pearson RM, Zammit S, Lewis G, Jones PB. Association of serum interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein in childhood with depression and psychosis in young adult life: a population-based longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1121-1128. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Severance EG, Yolken RH, Eaton WW. Autoimmune diseases, gastrointestinal disorders and the microbiome in schizophrenia: more than a gut feeling. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(1):23-35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421-427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foldager L, Köhler O, Steffensen R, et al. Bipolar and panic disorders may be associated with hereditary defects in the innate immune system. J Affect Disord. 2014;164:148-154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, et al. ; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature. 2016;530(7589):177-183. doi: 10.1038/nature16549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betts KS, Salom CL, Williams GM, Najman JM, Alati R. Associations between self-reported symptoms of prenatal maternal infection and post-traumatic stress disorder in offspring: evidence from a prospective birth cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:241-247. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Köhler O, Petersen L, Mors O, et al. Infections and exposure to anti-infective agents and the risk of severe mental disorders: a nationwide study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):97-105. doi: 10.1111/acps.12671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):30-33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):38-41. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pottegård A, Broe A, Aabenhus R, Bjerrum L, Hallas J, Damkier P. Use of antibiotics in children: a Danish nationwide drug utilization study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(2):e16-e22. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573-581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):91-94. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Broadwell RD. Passage of cytokines across the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1995;2(4):241-248. doi: 10.1159/000097202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quan N, Whiteside M, Herkenham M. Time course and localization patterns of interleukin-1β messenger RNA expression in brain and pituitary after peripheral administration of lipopolysaccharide. Neuroscience. 1998;83(1):281-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46-56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, Correll CU, Nielsen J. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Dan Med J. 2013;60(2):A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong MS, Umetsu DT, Mandl KD. Consequences of antibiotics and infections in infancy: bugs, drugs, and wheezing. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(5):441-445.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hviid A, Svanström H, Frisch M. Antibiotic use and inflammatory bowel diseases in childhood. Gut. 2011;60(1):49-54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.219683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikkelsen KH, Knop FK, Frost M, Hallas J, Pottegård A. Use of antibiotics and risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(10):3633-3640. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kardas P, Devine S, Golembesky A, Roberts C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of misuse of antibiotic therapies in the community. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;26(2):106-113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dekker AR, Verheij TJ, van der Velden AW. Inappropriate antibiotic prescription for respiratory tract indications: most prominent in adult patients. Fam Pract. 2015;32(4):401-407. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frisell T, Öberg S, Kuja-Halkola R, Sjölander A. Sibling comparison designs: bias from non-shared confounders and measurement error. Epidemiology. 2012;23(5):713-720. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31825fa230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, 8th Edition (ICD-8) and ICD-10 Codes for Site and Type of the Infection Resulting in a Hospitalization

eTable 2. Anti-Infective Agents According to the Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical System (ATC) From the World Health Organization (WHO), Subdivided Into Antibacterial, Antiviral, Antimyotic and Antiparasitic Products

eTable 3. The Most Frequently Used Antibiotics Within the Study Population, According to the Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical System (ATC) From the World Health Organization (WHO), and Subdivided Into Broad-Spectrum, Moderate-Spectrum, Narrow-Spectrum, and Topical Antibiotics

eTable 4. Characteristics of the Study Population (N=1,098,930) at the End of Follow-up

eTable 5. Risk for Any Treated Mental Disorder Among All Individuals Born in Denmark Between 1995 and 2012 According to Hospitalizations With Infections and Prescriptions for Anti-infective Agents

eTable 6. Risk of the Specific Mental Disorders Among Individuals With Infections Treated With Anti-infective Agents or Requiring Hospitalizations

eTable 7. Risk for Any Treated Mental Disorder Among Persons Born Between 1995 and 2012 According to the Amount of Different Groups of Anti-infective Agents

eResults. Supplementary Results