Key Points

Question

How does amblyopia influence self-perception in children ages 8 to 13 years?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study, children with amblyopia had lower scholastic, social, and athletic competence scores as derived from the Self-perception Profile for Children than control children. Among children with amblyopia, the self-perception of scholastic competence was associated with reading speed, and the self-perception of scholastic, social, and athletic competence was associated with aiming and catching skills.

Meaning

These results suggest lower self-perception and its association with reading speed and motor skills highlight the potentially wide-ranging influence of altered visual development in children in their everyday lives.

Abstract

Importance

Reading and eye-hand coordination deficits in children with amblyopia may impede their ability to demonstrate their knowledge and skills, compete in sports and physical activities, and interact with peers. Because perceived scholastic, social, and athletic competence are key determinants of self-esteem in school-aged children, these deficits may influence a child’s self-perception.

Objective

To determine whether amblyopia is associated with lowered self-perception of competence, appearance, conduct, and global self-worth and whether the self-perception of children with amblyopia is associated with their performance of reading and eye-hand tasks.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2016 to June 2017 at the Pediatric Vision Laboratory of the Retina Foundation of the Southwest and included healthy children in grades 3 to 8, including 50 children with amblyopia; 13 children without amblyopia with strabismus, anisometropia, or both; and 18 control children.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Self-perception was assessed using the Self-perception Profile for Children, which includes 5 domains: scholastic, social, and athletic competence; physical appearance; behavioral conduct; and a separate scale for global self-worth. Reading speed and eye-hand task performance were evaluated with the Readalyzer (Bernell) and Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd Edition. Visual acuity and stereoacuity also were assessed.

Results

Of 50 participants, 31 (62%) were girls, 31 (62%) were non-Hispanic white, 6 (12%) were Hispanic white, 3 (6%) were African American, 4 (8%) were Asian/Pacific Islander, and 3 (6%) were more than 1 race/ethnicity, and the mean [SD] age was 10.6 [1.3] years. Children with amblyopia had significantly lower scores than control children for scholastic (mean [SD], 2.93 [0.74] vs 3.58 [0.24]; mean [SD] difference, 0.65 [0.36]; 95% CI, 0.29-1.01; P = .004), social (mean [SD], 2.95 [0.64] vs 3.62 [0.35]; mean [SD] difference, 0.67 [0.32]; 95% CI, 0.35-0.99] P < .001), and athletic (mean [SD], 2.61 [0.65] vs 3.43 [0.52]; mean [SD] difference, 0.82 [0.34]; 95% CI, 0.48-1.16; P = .001) competence domains. Among children with amblyopia, a lower self-perception of scholastic competence was associated with a slower reading speed (r = 0.49, 95% CI, 0.17-0.72; P = .002) and a lower self-perception of scholastic, social, and athletic competence was associated with worse performance of aiming and catching (scholastic r = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.16-0.71; P = .007; social r = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.35-0.81; P < .001; athletic r = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.21-0.75; P = .003). No differences in the self-perception of physical appearance (mean [SD], 3.32 [0.63] vs 3.64 [0.40]), conduct (mean [SD], 3.09 [0.56] vs 3.34 [0.66]), or global self-worth (mean [SD], 3.42 [0.42] vs 3.69 [0.36]) were found between the amblyopic and control groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that lower self-perception is associated with slower reading speed and worse motor skills and may highlight the wide-ranging effects of altered visual development for children with amblyopia in their everyday lives.

This cross-sectional study examines the association of amlyopia with self-perception of scholastic, social, and athletic competence in school-aged US children.

Introduction

Reading and eye-hand coordination deficits have been reported in children with amblyopia.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 These limitations may impede the ability of students with amblyopia to demonstrate their knowledge and skills, compete in sports and physical activities, and interact with their peers. Perceived scholastic, social, and athletic competence, along with physical appearance, are key determinants of self-esteem in school-age children.14,15,16 Thus, the limitations that are associated with amblyopia may influence a child’s self-perception.

Numerous amblyopia studies have focused on the association of patching treatments with self-esteem, stigma, bullying, and family stress.17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 On the other hand, to our knowledge, few studies have assessed how amblyopia itself affects self-perception. In a study of adults who were asked to recall how anisometropic amblyopia affected them during their school years, 76% reported that amblyopia affected their self-image, 52% reported that amblyopia interfered with school, and 40% reported that amblyopia interfered with sports.22 Using the Rosenberg Self-esteem questionnaire, a diverse group of students age 11 to 13 years with strabismic, anisometropic, combined mechanism, or deprivation amblyopia had no problems with self-esteem, but the 10-item scale was deemed by the authors to be insensitive because of ceiling effects.26 Low social acceptance scores were found in a group of 9-year-old children that included some with amblyopia and others who had recovered but had a history of amblyopia.27 However, this latter study was conducted more than a decade ago, an era during which amblyopic children were patching much more than the current recommendation of 2 hours per day (https://www.aao.org/ preferred-practice-pattern/amblyopia-ppp-2017) and were wearing their patches to school. It is not surprising that the lower social acceptance scores were associated with a history of patching.27 The goals of this study were to determine whether children’s self-perception is influenced by amblyopia in grades 3 to 8, examine whether self-perception scores are associated with deficits in performance in reading and motor skills tasks, and evaluate whether there are specific clinical factors that are associated with self-perception in children with amblyopia.

Methods

Participants

Fifty children with amblyopia in grades 3 to 8 (age 8 to 13 years) were enrolled. The eligibility criteria were a current diagnosis of strabismic, anisometropic, or combined-mechanism amblyopia (diagnostic criteria were developed by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group for the Amblyopia Treatment Studies28); an amblyopic eye best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 0.2 logMAR or worse; a fellow eye BCVA of 0.1 logMAR or better; or an interocular difference in BCVA of 0.2 logMAR or greater. To evaluate the effect of amblyogenic factors in the absence of amblyopia, 13 age-similar children without amblyopia with anisometropia, strabismus, or both who had no history of amblyopia diagnosis or patching treatment were enrolled. All children with strabismus had achieved good alignment (<5 prism diopters) with spectacles and/or surgery at the time they participated in this study. As a comparison group, 18 age-similar controls were also enrolled. None of the children were born prematurely (>32 weeks’ postmenstrual age), had coexisting ocular or systemic disease, or had a history of congenital malformation or infection. Because the study included printed questionnaires, a reading test, and motor skills testing, additional exclusion criteria were dyslexia, enrollment in a reading intervention program, and a primary language other than English. The characteristics of each group are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristic | With Amblyopia | Without Amblyopiaa | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children, No. | 50 | 13 | 18 |

| Self-perception | 50 | 13 | 18 |

| Vision | 50 | 13 | 18 |

| Reading speed | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Motor skills | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| Female, No. (%) | 31 (62) | 7 (54) | 10 (56) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 10.6 (1.3) | 10.7 (1.2) | 10.6 (1.4) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 31 (62) | 7 (54) | 12 (67) |

| Hispanic white | 6 (12) | 1 (8) | 2 (11) |

| African American | 3 (6) | 2 (15) | 1 (6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (8) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) |

| More than 1 race/ethnicity | 3 (6) | 1 (8) | 2 (11) |

| Declined to provide information | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Etiology, No. (%) | |||

| Strabismus | 21 (42) | 4 (31) | NA |

| Anisometropia | 19 (38) | 5 (38) | NA |

| Combined | 10 (20) | 4 (31) | NA |

| Amblyopic eye visual acuity (logMAR), No. (%)b | |||

| ≤0.1 | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 18 (100) |

| 0.2-0.3 | 30 (60) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 0.4-0.5 | 12 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 0.6-0.7 | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| >0.7 | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.41 (0.33) | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.07(0.05) |

| (Range) | (0.2 to 1.9) | (−0.1 to 0.1) | (−0.1 to 0.1) |

| Fellow eye visual acuity (logMAR), No. (%)c | |||

| −0.1 | 34 (68) | 7 (50) | 13 (72) |

| 0.0 | 13 (26) | 5 (43) | 4 (22) |

| 0.1 | 3 (6) | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| Mean (SD) | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.00 (0.02) | −0.07 (0.05) |

| (Range) | (−0.1 to 0.1) | (−0.1 to 0.1) | (−0.1 to 0.1) |

| Stereoacuity (log arcsec), mediand (range) | 4.00 (1.6-nil) | 2.30 (1.6-nil) | 1.50 (1.3-1.8) |

| Amblyopia treatment, No. (%) | |||

| Current eyeglass wear | 42 (84) | 11 (85) | 0 (0) |

| History of eyeglass wear | 48 (96) | 12 (92) | 0 (0) |

| Current patching | 9 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| History of patching | 45 (90) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Children without amblyopia had no history of amblyopia and had no prior amblyopia treatment.

Amblyopic eye best-corrected visual acuity or, for children without amblyopia and control participants, worse eye best-corrected visual acuity.

Fellow eye best-corrected visual acuity or, for children without amblyopia and control participants, better eye.

Nil stereoacuity was assigned a value of 4.0 log arc per second.

Written informed consent was obtained from a parent after an explanation of the nature and possible consequences of the study. In addition, written informed assent was obtained from children age 10 to 12 years. All procedures and the protocol were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and complied with the requirements of the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Vision

Every participant with or without amblyopia had a comprehensive eye examination that was performed by a fellowship-trained pediatric ophthalmologist who diagnosed whether amblyopia was present and identified the etiologic factors. Children wore optical correction, if needed, in accordance with American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus guidelines (https://aapos.org//client_data/files/2017/506_aaposmedicalneedforglasses.pdf). The best-corrected visual acuity was obtained for each eye with an opaque occluder patch and the electronic Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study method.29,30 Random-dot stereoacuity was evaluated using the Randot Preschool Stereoacuity Test (Stereo Optical Co, Inc) and the Stereo Butterfly Test (Stereo Optical Co, Inc), which were administered and scored according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Self-perception

Self-perception was assessed with the Self-perception Profile for Children.31 This instrument uses a multidimensional approach to the measurement of self-perception. Beginning in middle childhood, children are able to make domain-specific evaluations of their competence or adequacy in different arenas.32 The Self-perception Profile for Children includes 5 specific domains: scholastic competence (perceived cognitive competence, as applied to schoolwork), social competence (perceived competence in skills that are needed to make friends, be popular, and have others like you), athletic competence (perceived competence in sports and outdoor games), physical appearance (feeling happy about looks), and behavioral conduct (the degree to which people do the right thing and avoid trouble). A sixth domain (not a composite score) evaluates the child’s overall sense of their worth as a person (ie, global self-worth; how happy with the way they are leading their lives and the way they are as human beings).

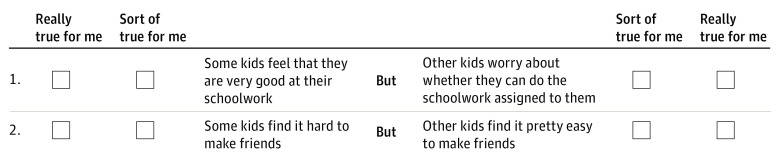

For each domain, there are 6 items in a structured 2-alternative format that is designed to offset the tendency to give socially desirable responses. Specifically, the items are formulated to imply that half of the children in the world view themselves one way and half the other way, which legitimizes either choice. Two sample questions from the scholastic scale are provided in Figure 1. The child was first asked to decide which kids he or she was most like for each statement. Once the child made this choice, he or she was asked to choose whether this is “really true for me” of “sort of true for me.” Harter,31 the developer of the Self-perception Profile for Children, argues that the effectiveness of this approach lies in the implication that half of the children in the world view themselves one way and half the other way, legitimizing either choice. Refining their answer into the “really true for me” or “sort of true for me” category broadens the range of choices into a 4-point scale (1 = lowest perceived competence or adequacy; 4 = highest perceived competence or adequacy). Within each domain, the first alternative is phrased in a positive manner for 3 of the 6 items and in a negative manner for the remaining 3 questions (Figure 1). A mean score was calculated for each subscale.

Figure 1. Sample Questions from the Self-perception Profile for Children.

The Self-perception Profile for Children was administered according to the published instructions.33 All children had practice with a sample question to ensure that they understood the 2-alternative format and the subsequent choice of “really true for me” of “sort or true for me.” For children in grades 3 and 4, the entire questionnaire was read to them by a research staff member. Older children sat with the research staff member but could read the questionnaire on their own, using the staff member as a resource if they had any questions or difficulty understanding any words. The child’s parent was ideally seated in the next room, but if that was not possible, they sat behind the child and were instructed not to assist or coach the child in any way. Self-perception scale scores were not available to the examiner who was responsible for testing reading and motor skills.

Reading

Reading skill was assessed in children with amblyopia during the binocular viewing with the Readalyzer (Compevo AB), an infrared eye movement recording system that was mounted in goggles that were worn over the child’s habitual optical correction.4,5 The child sat at eye level at a comfortable, habitual reading distance (35-40 cm) and was required to silently read printed paragraphs of text (12 lines; 100 words) from a booklet. The child first read a grade level–1 paragraph that served as a practice run, then a paragraph at the last grade level completed. Ten yes/no comprehension questions followed each silent reading. Recordings were considered acceptable for analysis if the comprehension was 80% or greater and the tracking reliability was 70% or greater. Reading speed (words per minute) was used as the outcome measure.

Motor Skills

Children with amblyopia were tested with the Movement Assessment Battery for Children 2 (MABC-2), a standardized test of motor skills and coordination that is administered in age bands (age 8–10 years; age 11-13 years for this study). The Movement Assessment Battery for Children 2 consists of 8 tasks that compose 3 subscales: manual dexterity (unimanual, bimanual, and drawing trail), aiming and catching, and balance (static and dynamic). Raw scores per task are converted into standardized scores, with higher scores indicating a better performance.

Analysis

A 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate group differences (amblyopic, nonamblyopic, and normal control) for each self-perception domain (scholastic competence, social competence, athletic competence, physical appearance, behavioral conduct, and global self-worth). Significant ANOVAs were followed with post hoc pairwise comparisons of the amblyopic and nonamblyopic groups with the controls (Bonferroni-adjusted α = .025). Pearson r correlations were conducted for children with amblyopia only to examine the associations between task performance (reading speed and motor skills) and self-perception domain scores. Pearson r correlations also were conducted to determine whether clinical factors (amblyopic eye best-corrected visual acuity, stereoacuity) were associated with self-perception domain scores. Lastly, independent t tests were conducted to determine whether children with amblyopia with strabismus and children with amblyopia without strabismus differed on any self-perception domain.

Results

Self-perception and Global Self-worth

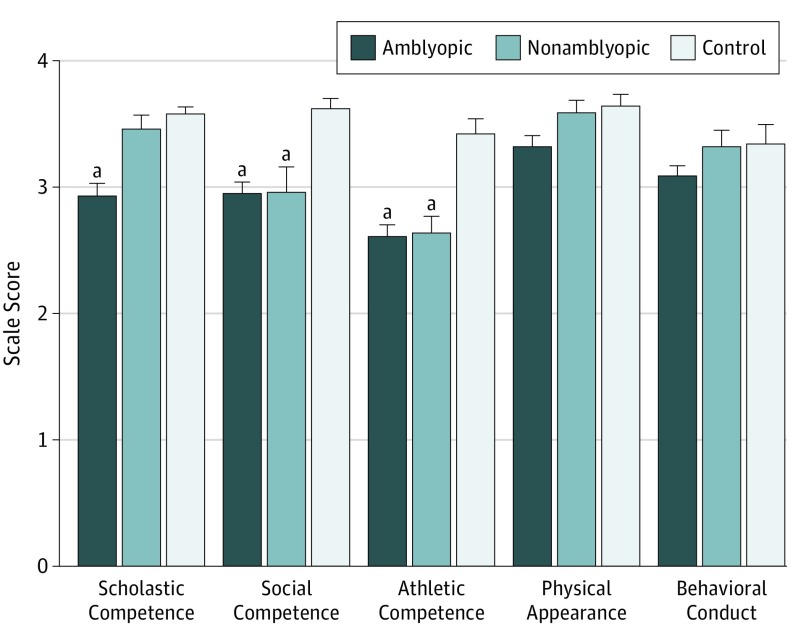

The mean self-perception scale scores for children with and without amblyopia and controls are summarized in Figure 2 and Table 2. Scholastic, social, and athletic competence scores were significantly different among groups (F2,78, 9.04, 8.42, and 12.54, respectively; P < .004 for all 3 ANOVAs). Children with amblyopia had lower scores than control children for scholastic (t66 = 3.80; P <.001), social (t66 = 4.24; P < .001), and athletic competence (t66 = 4.50; P < .001), but did not significantly differ from controls for the self-perception of physical appearance (t66 = 2.00; P = .05) or behavioral conduct (t66 = 1.52; P = .13). Children without amblyopia had significantly lower scores than control children for social (t29 = 3.41; P = .02) and athletic competence (t29 = 4.40; P < .001) but did not significantly differ from controls for the self-perception of scholastic competence (t29 = 1.31; P = .20), physical appearance (t29 = 0.37; P = .72), or behavioral conduct (t29 = 0.09; P = .93). Neither children with or without amblyopia differed significantly from controls for global self-worth (t66 = 1.53; P = .13 and t29 = 1.84; P = .08, respectively).

Figure 2. Self-perception Scale for Children Domain Scores for Amblyopic, Nonamblyopic, and Control Groups.

The vertical bars show standard errors of the mean.

aThe group’s mean score was significantly lower than the control group’s mean score.

Table 2. Domain Scale Scores.

| Category | Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Amblyopic | Nonamblyopic | Control | |

| Scholastic | 2.93 (0.74)a | 3.46 (0.41) | 3.58 (0.24) |

| Social | 2.95 (0.64)a | 2.96 (0.73)b | 3.62 (0.35) |

| Athletic | 2.61 (0.65)a | 2.64 (0.49)a | 3.43 (0.52) |

| Physical appearance | 3.32 (0.63) | 3.59 (0.35) | 3.64 (0.40) |

| Behavioral conduct | 3.09 (0.56) | 3.32 (0.47) | 3.34 (0.66) |

| Global self-worth | 3.42 (0.42) | 3.54 (0.44) | 3.69 (0.36) |

P < .001 compared with controls.

P < .005 compared with controls.

Self-perception and Task Performance in Amblyopia

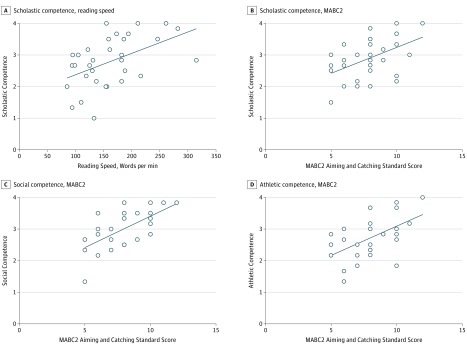

The associations between competence scores and task performance were examined for children with amblyopia (Figure 3). Scholastic competence scores were positively associated with reading speed (r = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.17-0.72; P = .002). Scholastic, social, and athletic competence scores were positively associated with aiming and catching (scholastic competence, r = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.16-0.71; P = .007; social competence, r = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.35-0.81; P < .001; athletic competence, r = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.21-0.75; P = .003). No significant correlations between self-perception domain scores and manual dexterity or balance scores were observed.

Figure 3. Associations Between Task Performance Measures and Self-perception Domain Scores.

The solid lines represent best-fit linear regressions. MABC2 indicates Movement Assessment Battery for Children 2.

Self-perception and Clinical Factors in Amblyopia

No significant correlations were found for amblyopic eye visual acuity or stereoacuity and domain scores. The scores of subgroups of children with amblyopia with or without strabismus did not differ significantly in any domain. Because nearly every child with amblyopia had a history of treatment with eyeglasses and patching, we were not able to compare the domain scores of the subgroups with and without these treatments.

Discussion

Amblyopia influences self-perception in children enrolled in third through eighth grade, especially the self-perception of scholastic, social, and athletic competence. Children with amblyopia had significantly lower scholastic, social, and athletic competence scores than control children. The self-perception of scholastic competence was associated with reading speed and the self-perception of scholastic, social, and athletic competence was associated with the performance of aiming and catching skills. No differences in the self-perception of physical appearance or behavioral conduct and no differences in global self-worth were found among amblyopic, nonamblyopic, and control groups.

Children without amblyopia with strabismus, anisometropia, or both did not differ from controls in their self-perception of scholastic competence. However, the sample size was small (n = 13), limiting our power to determine whether subtle differences were present. The finding of no significant difference between children without amblyopia and controls is consistent with our previous report that amblyopia, not the associated etiologic factors of strabismus or anisometropia, is the key factor in slow reading in school-age children with amblyopia.4,5 Slow binocular silent reading in children with amblyopia is associated with ocular motor dysfunction. Children with amblyopia make more forward saccades than controls when reading, most likely because fixation instability results in saccades that miss the preferred landing position near the center of a word, thus requiring secondary corrective saccades to acquire the optimal position for decoding.34,35,36

Our finding that children with amblyopia and children without amblyopia with strabismus, anisometropia, or both have comparably lower social and athletic competence scores than controls suggests that discordant binocular visual experience, and not amblyopia, is influencing self-perception in these domains. Because self-perception is already developing before age 5 years, largely based on perceived competence and perceived social acceptance we, unlike others,9,10,27 included only children with no history of amblyopia diagnosis or patching treatment in our nonamblyopic group. Because the focus of this study was the influence of amblyopia on self-perception, we did not enroll children with strabismus of more than 4 prism diopters.

The self-perception of both social and athletic competence were associated with performance on aiming and catching tasks. A moderate association between social competence and athletic competence has been reported previously.33 While it is difficult to infer causality, it has been suggested that athletic prowess may lead to greater social acceptance or popularity during grades 3 to 8.33

Nearly all of the children with amblyopia and children without amblyopia had spectacle correction while none of the healthy controls wore eyeglasses. Because the children with and without amblyopia differed from controls in their self-perception of social and athletic domains, it is possible that wearing eyeglasses contributed to their altered self-perception of social and athletic competence. However, for the scholastic domain, only the children with amblyopia had lower scores, which was consistent with an effect solely due to amblyopia. This hypothesis is supported by the association between reading speed and the self-perception of scholastic competence.

Limitations

It remains unknown whether improvements in sensory function as a result of amblyopia treatment will result in improved self-perception of scholastic, social, and athletic competence. The lack of an association between visual acuity and stereoacuity and competence domain scores suggests that amblyopia treatment may not improve self-perception. On the other hand, the association between self-perception of scholastic competence and reading speed, along with our prior finding that decreased reading speed in amblyopia results primarily from an abnormally large number of forward saccades,4,5 suggests that amblyopia treatment may improve the self-perception of scholastic competence. Along the same line, data showing that motor skills improve following amblyopia treatment11 suggest that treatment may improve the self-perception of athletic and possibly social competence.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that lower self-perception is associated with slower reading speed and worse motor skills and may highlight the wide-ranging effects of altered visual development on children with amblyopia in their everyday lives.

References

- 1.Grant S, Conway ML. Reach-to-precision grasp deficits in amblyopia: effects of object contrast and low visibility. Vision Res. 2015;114:100-110. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant S, Melmoth DR, Morgan MJ, Finlay AL. Prehension deficits in amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1139-1148. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanonidou E, Proudlock FA, Gottlob I. Reading strategies in mild to moderate strabismic amblyopia: an eye movement investigation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(7):3502-3508. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly KR, Jost RM, De La Cruz A, Birch EE. Amblyopic children read more slowly than controls under natural, binocular reading conditions. J AAPOS. 2015;19(6):515-520. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly KR, Jost RM, De La Cruz A, et al. Slow reading in children with anisometropic amblyopia is associated with fixation instability and increased saccades. J AAPOS. 2017;21(6):447-451.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor AR, Birch EE, Anderson S, Draper H. Relationship between binocular vision, visual acuity, and fine motor skills. Optom Vis Sci. 2010;87(12):942-947. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181fd132e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor AR, Birch EE, Anderson S, Draper H; FSOS Research Group . The functional significance of stereopsis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(4):2019-2023. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stifter E, Burggasser G, Hirmann E, Thaler A, Radner W. Monocular and binocular reading performance in children with microstrabismic amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(10):1324-1329. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.066688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suttle CM, Melmoth DR, Finlay AL, Sloper JJ, Grant S. Eye-hand coordination skills in children with and without amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(3):1851-1864. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webber AL, Wood JM, Gole GA, Brown B. The effect of amblyopia on fine motor skills in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(2):594-603. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webber AL, Wood JM, Thompson B. Fine motor skills of children with amblyopia improve following binocular treatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(11):4713-4720. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant S, Suttle C, Melmoth DR, Conway ML, Sloper JJ. Age- and stereovision-dependent eye-hand coordination deficits in children with amblyopia and abnormal binocularity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(9):5687-57015. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanonidou E, Gottlob I, Proudlock FA. The effect of font size on reading performance in strabismic amblyopia: an eye movement investigation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(1):451-459. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips DA. Socialization of perceived academic competence among highly competent children. Child Dev. 1987;58(5):1308-1320. doi: 10.2307/1130623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pomerantz EM, Ruble DN, Frey KS, Greulich F. Meeting goals and confronting conflict: children’s changing perceptions of social comparison. Child Dev. 1995;66(3):723-738. doi: 10.2307/1131946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piek JP, Baynam GB, Barrett NC. The relationship between fine and gross motor ability, self-perceptions and self-worth in children and adolescents. Hum Mov Sci. 2006;25(1):65-75. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2005.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felius J, Chandler DL, Holmes JM, et al. ; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group . Evaluating the burden of amblyopia treatment from the parent and child’s perspective. J AAPOS. 2010;14(5):389-395. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes JM, Beck RW, Kraker RT, et al. ; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group . Impact of patching and atropine treatment on the child and family in the amblyopia treatment study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(11):1625-1632. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.11.1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koklanis K, Abel LA, Aroni R. Psychosocial impact of amblyopia and its treatment: a multidisciplinary study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34(8):743-750. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loudon SE, Passchier J, Chaker L, et al. Psychological causes of non-compliance with electronically monitored occlusion therapy for amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(11):1499-1503. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.149815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams C, Horwood J, Northstone K, Herrick D, Waylen A, Wolke D; ALSPAC Study Group . The timing of patching treatment and a child’s wellbeing. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(6):670-671. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.091082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packwood EA, Cruz OA, Rychwalski PJ, Keech RV. The psychosocial effects of amblyopia study. J AAPOS. 1999;3(1):15-17. doi: 10.1016/S1091-8531(99)70089-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horwood J, Waylen A, Herrick D, Williams C, Wolke D. Common visual defects and peer victimization in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(4):1177-1181. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hrisos S, Clarke MP, Wright CM. The emotional impact of amblyopia treatment in preschool children: randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1550-1556. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drews-Botsch CD, Hartmann EE, Celano M; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group . Predictors of adherence to occlusion therapy 3 months after cataract extraction in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. J AAPOS. 2012;16(2):150-155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.12.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson GA, Welch D. Does amblyopia have a functional impact? findings from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(2):127-134. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02842.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webber AL, Wood JM, Gole GA, Brown B. Effect of amblyopia on self-esteem in children. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85(11):1074-1081. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31818b9911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of atropine vs. patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(3):268-278. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.3.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moke PS, Turpin AH, Beck RW, et al. Computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the amblyopia treatment study visual acuity testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(6):903-909. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(01)01256-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck RW, Moke PS, Turpin AH, et al. A computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the early treatment of diabetic retinopathy study testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(2):194-205. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01825-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harter S. The Construction of the Self: Developmental and Socio-Cultural Foundations. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harter S. The Construction of the Self. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harter S. Self-Perception Profile for Children: Manual and Questionnaires. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niechwiej-Szwedo E, Chandrakumar M, Goltz HC, Wong AM. Effects of strabismic amblyopia and strabismus without amblyopia on visuomotor behavior, I: saccadic eye movements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(12):7458-7468. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niechwiej-Szwedo E, Goltz HC, Chandrakumar M, Hirji ZA, Wong AM. Effects of anisometropic amblyopia on visuomotor behavior, I: saccadic eye movements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(12):6348-6354. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McConkie GW, Kerr PW, Reddix MD, Zola D. Eye movement control during reading, I: the location of initial eye fixations on words. Vision Res. 1988;28(10):1107-1118. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(88)90137-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]