Key Points

Question

Do current glaucoma staging systems underestimate severity when macular damage is present?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 57 participants, the main glaucoma severity staging systems classified about 70% of eyes with confirmed macular damage as having early glaucoma.

Meaning

These findings suggest current glaucoma staging systems tend to underestimate severity when not including 10-2 visual fields and high-resolution macular imaging in assessments of macular damage; if these results are confirmed and generalizable, new systems using macular measurements (from 10-2 and optical coherence tomography results) might improve glaucoma severity staging.

This cross-sectional study compares multiple methods of assessing the visual field to test the hypothesis that current glaucoma staging systems underestimate glaucoma severity by not detecting macular damage.

Abstract

Importance

Macular function is important for daily activities but is underestimated when tested with 24-2 visual fields, which are often used to classify glaucoma severity.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that current glaucoma staging systems underestimate glaucoma severity by not detecting macular damage.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study was carried out in a glaucoma referral practice. The eyes of participants with manifest glaucoma and 24-2 mean deviation (MD) better than −6 dB were included. All participants were tested with 24-2, 10-2 visual fields, and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the optic disc and macula.

Exposures

Macular damage was based on the topographic agreement between visual field results and retinal ganglion cell plus inner plexiform layer probability plots. Classifications from the Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson (HPA), visual field index (VFI), and Brusini staging systems were examined and compared with visual field and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography results.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The association between the presence of macular damage and glaucoma severity scores.

Results

Fifty-seven eyes of 57 participants were included; 33 participants (57%) were women, and 43 (75%) were white. Their mean (SD) age was 57 (14) years. Forty-eight of the eyes (84% [95% CI, 72%-92%]) had macular damage by the study definition. These had a 24-2 MD mean (SD) of −2.5 (1.8); corresponding results for the 10-2 MD were −3.0 (2.4) dB and for the VFI were 94.2% (4.5%). The HPA system classified 70% (95% CI, 55%-83%) of eyes with macular damage as having early defects; the VFI system classified 81% (95% CI, 67%-91%) of eyes with macular damage as having early defects, and the Brusini system 68% (95% CI, 53%-81%).

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that current glaucoma staging systems based on 24-2 (or 30-2) visual fields underestimate disease severity and the presence of macular damage. If these results are confirmed and generalizable to other participants, new systems using macular measures (from 10-2 and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography results) might improve staging of glaucoma severity.

Introduction

Standard automated perimetry (SAP) with a fixed 6 × 6° grid testing the central 24° of the visual field (eg, 24-2 and 30-2 tests) is the commonly used reference standard to define the presence of glaucomatous functional loss.1 In clinical practice and randomized clinical trials, the results of this modality of testing have been used as main outcome measures to determine glaucoma onset2,3 and progression4,5,6 often aided by optic nerve imaging techniques.

There is growing evidence that 24-2 SAP results can miss damage within the central 10° of the visual field that would otherwise be detected if one used a denser grid (2 × 2°), such as that tested with 10-2 SAP.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 Furthermore, studies using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) have shown that macular damage in early glaucoma is much more common than previously thought and is often present in eyes with 24-2 mean deviation (MD) better (ie, closer to 0) than −6 dB.16,17,18,19,20

Because of their importance in clinical and research settings, and given their substantial association with measures of vision-related quality of life,21,22 24-2 (or 30-2) SAP metrics have traditionally been used to stage glaucoma severity.23 Although some of these staging systems take into account the presence of central field damage as a sign of more severe disease,24,25 an important caveat they all share is the lack of a finer assessment of macular damage, whether by means of incorporating 10-2 fields or SD-OCT macular scans.

Given that 24-2 SAP results underestimate the prevalence and degree of glaucomatous damage of the macula,11,19 we hypothesized that glaucoma staging systems also underestimate glaucoma severity, particularly among eyes often diagnosed as early damage. To test this hypothesis, we define macular damage by a combination of topographically matching SD-OCT results and 10-2 SAP results and examine how 3 commonly used staging systems classify this damage.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was approved by the institutional review boards of Columbia University Medical Center and the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants.

We included 57 eyes of 57 participants with glaucoma (mean age [SD], 57 [14] years) with 24-2 SAP results MDs better than −6 dB and a spherical refractive error less than 6 diopters (D). All eyes were classified as having established glaucoma by 2 glaucoma experts (J.M.L. and D.M.B.) and had signs of glaucomatous optic neuropathy on disc photographs and 24-2 visual fields (Swedish Interactive Testing Algorithm–Standard, Humphrey Field Analyzer; Carl Zeiss Meditec) with abnormalities consistent with glaucoma. Glaucoma experts also had access to participants’ clinical and family histories, intraocular pressure, SD-OCT scan results, and 10-2 visual field results to help in their determination. Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study are described elsewhere.17

Definition of Macular Damage

Macular damage was defined by 10-2 SAP and macular SD-OCT evidence of retinal ganglion cells plus inner plexiform (RGCP) layer probability maps, as previously described.8,16,18,19 In brief, the total deviation and pattern deviation (PD) plots of the 10-2 results were reviewed in combination and clusters of points with probabilities less than 5% were circled by an investigator (D.C.H.) masked to the SD-OCT results. These regions of abnormality were then overlaid on top of the RGCP probability maps after the investigator flipped to field view. Macular damage was deemed present if the region(s) of 10-2 abnormality topographically matched areas of the macular RGCP probability maps with probabilities less than 5%. Figure 1 depicts examples of eyes with macular damage.

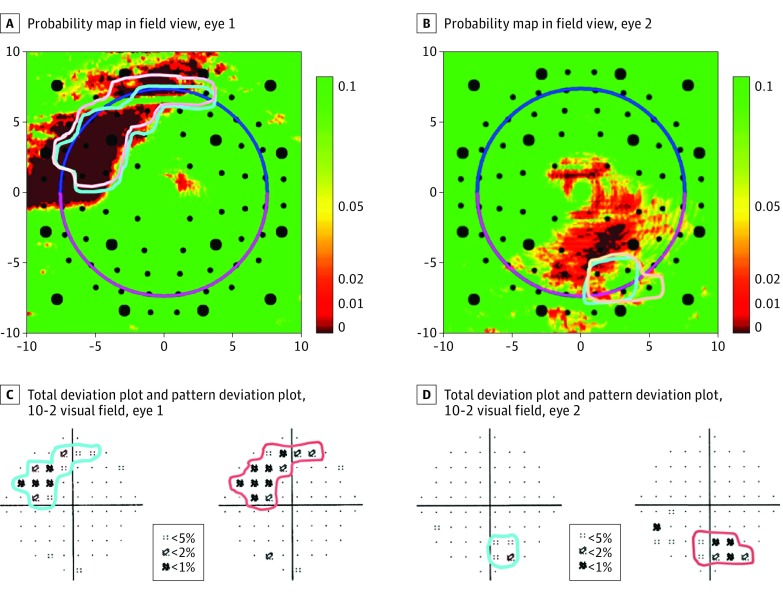

Figure 1. Definition of Macular Damage.

A and B, Field view of the retinal ganglion cells plus inner plexiform layer probability maps derived from spectral-domain optical coherence tomography cube scans of the maculae from 2 different study participants. Per the continuous probability scale, smaller values (red) suggest the greatest likelihood of abnormality, whereas higher values (green) suggest normality. C and D, The 10-2 visual fields with total and pattern deviation plots from the eyes shown in A and B, respectively. In both eyes, the 10-2 and retinal ganglion cells plus inner plexiform abnormalities matched topographically.

We then classified each eye with regard to glaucoma severity in multiple glaucoma staging systems. In the Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson (HPA) criteria (eTable in the Supplement),24 3 main parameters were used for staging: the MD, the number of test points depressed below predefined probabilities on the PD plots, and loss of threshold sensitivity within the central 5° of the visual field.

The Glaucoma Visual Field Staging System (GVFSS)25 consists of 3 parameters reported in the format 1/2/3. Parameter 1 describes the severity as per the visual field index (VFI),26 parameter 2 determines the location of the defect per the eccentricity in degrees, and parameter 3 displays the topographic extent of damage based on the hemifield involved and the connection to the blind spot. A PD plot with 2 or more adjacent points, all of which depressed at P < .05, with at least 1 of those points depressed at P < .01 or 1 nonedge point on the PD plot depressed at P < .005, is used to determine the presence of damage. The VFI system classifies a visual field result as early (designated E) when VFI values are better than 91%; moderate (M) when values are between 78% and 91%; and severe (S) when 78% or worse. eFigure 1 in the Supplement shows 4 examples using this staging system. The present analyses will be focused on the VFI component of this staging system.

Finally, the Brusini Glaucoma Staging System 2 (GSS2)27 is based on a chart that plots global metrics from the Humphrey Field Analyzer or the Octopus perimeter (Haag Streit, GmbH). For the purpose of the present analyses, we only used the metrics from the Humphrey Field Analyzer: MD (plotted on the x-axis) and pattern standard deviation (PSD; on the y-axis). The solid curves are the borders between the stages of the system. The intersection between MD and PSD values defines whether the eye has localized, generalized, or mixed defects, as well as its stage, ranging from 0 (less severe) to 4 (more severe) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Comparison between the presence of macular damage and the staging systems was also completed. Figure 2 shows an example of an eye with macular damage based on study definitions. Because of the 24-2 MD, PD probability plots, and sensitivity of points in the central 5° of the visual field, this eye is staged as an early defect with the HPA system. Because of the VFI of 97%, it is staged as an early defect with the VFI component of the GVFSS. Because of the intersection of 24-2 MD and PSD on the GSS2 chart, the stage of severity is defined as stage 0 with the Brusini system. Figure 2A and B show the 24-2 and 10-2 results, with the respective total deviation and PD plots. Figure 2C shows the RGCP thickness map in retina view and the corresponding probability plot in field view (D) to enable direct comparisons with visual field results. Note that the superior arcuate defect on the 24-2 impinges on the central 10° of the visual field; this is more evident in the 10-2 plots, which show regions with excellent agreement with abnormal areas in the macular probability map.

Figure 2. Topographical Analyses.

Comparisons of retinal ganglion cell plus inner plexiform layer thickness maps of the macula of the same eye per 24-2 SAP results (A), 10-2 results (B), optical coherence tomographic scan thickness (C), and probability mapping (D). In A, test results include a visual field index of 97%, a mean deviation of −0.96 dB, and a pattern standard deviation of 2.14 dB (P < .05). In B, the mean deviation is −0.67 dB, and the pattern standard deviation is 1.72 dB (P < .05).

Results

Of the 57 participants, 33 (57%) were women, and 43 (75%) were white. Their mean (SD) age was 57 (14) years. Of the 57 patients with glaucoma diagnosis whose eyes had an MD better than −6 dB, 48 (84% [95% CI, 72%-92%]) had macular damage. The affected eyes had a mean (SD) of the 24-2 MD of −2.5 (1.8); the mean (SD) of the 10-2 MD was −3.0 (2.4) dB, and the mean (SD) of the VFI was 94.2% (4.5%).

Figure 3A shows the associations between HPA stages and the 24-2 MD values. Seven of the 57 eyes (12% [95% CI, 5.0%-23%]) were staged as having no or minimal defects, 36 (63% [95% CI, 49%-75%]) as having early-stage defects, and 14 (24% [95% CI, 14%-37%]) as having moderate defects. Among eyes with macular damage (n = 48), 10 (20% [95% CI, 10%-35%]) had no or minimal defect, 24 (50% [95% CI, 32%-64%]) had early-stage defects, and 14 (29% [95% CI, 17%-44%]) had moderate defects. All 14 eyes with moderate defects had macular damage.

Figure 3. Association Between Presence of Macular Damage and Staging System Results.

A, Comparison of Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson (HPA) criteria with 24-2 mean deviation (MD) results. B, Comparison of the visual field index (VFI) of the Glaucoma Visual Field Staging System results with 24-2 MD results. C, Comparison of Brusini Glaucoma Staging System 2 (GSS2) results with 24-2 MD results.

eFigure 3 in the Supplement shows an example of an eye classified as having no or minimal defects and an eye with early defects. The 10-2 result and the SD-OCT RGCP probability map showed topographically matching defects. The superior arcuate defect seen on both 24-2 and 10-2 results matched the RGCP loss seen on SD-OCT in both examples.

Figure 3B shows the association between the VFI and the 24-2 MD values for the VFI component of the GVFSS. Forty-eight of 57 eyes (84% [95% CI, 72%-92%]) were classified as having early defects and 9 (15% [95% CI, 7%-27%]) as having moderate defects. Among the 48 patients whose eyes had macular damage, 39 (81% [95% CI, 67%-91%]) had early defects and 9 (18% [95% CI, 8%-32%]) had moderate defects. All 9 patients whose eyes had moderate defects had macular damage. When looking at parameter 2 of this system (ie, the location of the defect based on the eccentricity in degrees), 7 of these 48 eyes (14% [95% CI, 6%-27%]) with macular damage had no abnormality within the central 10° of the 24-2. eFigure 3 in the Supplement shows 2 eyes classified as having early-stage defects based on the VFI (99% and 97%). The defect seen on the 10-2 results was missed in the 24-2 results, but it topographically matched the RGCP abnormality; 1 point at P < .05 fell just outside the central 10° of the 24-2 results of the GVFSS (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). In another image, both the 24-2 and 10-2 matched the RGCP defect.

Figure 3C shows the association between the Brusini GSS2 and 24-2 MD values. Thirty of 57 eyes (52% [95% CI, 39%-66%]) were classified as having stage 0 or borderline results, 11 as stage 1 (19% [95% CI, 10%-31%]), and 16 (28% [95% CI, 17%-41%]) as stage 2. Among the 48 eyes with macular damage, 23 (47% [95% CI, 33%-62%]) were classified as stage 0 or having borderline results, 10 (20% [95% CI, 10%-35%]) were stage 1, and 15 (31% [95% CI, 18%-46%]) were stage 2. Ten of the 11 eyes with stage 1 and 15 of the 16 eyes with stage 2 had macular damage. eFigure 3 in the Supplement shows 1 eye classified as stage 0 (MD, -0.5 dB; PSD, 2.6) and 1 as stage 1 (MD, -3.2 dB; PSD, 3.8). Both cases had abnormalities seen on both the 24-2 and 10-2 tests and confirmed with SD-OCT.

Discussion

We tested the hypothesis that current glaucoma staging systems, which are based on 24-2 or 30-2 SAP results, underestimate glaucoma severity, given that these tests do not adequately assess macular function. We found that in a sample of participants with glaucoma and MD better than −6 dB, nearly all had macular damage despite being classified as having no or early damage. Because of the importance of the macula for daily activities and quality of life,21,22,28 these findings suggest a fundamental flaw inherent to systems that aim to define glaucoma severity based exclusively on 24-2 or 30-2 visual fields. Most eyes commonly classified as having early disease may in fact require reclassification to severe glaucoma if the macula were evaluated with more adequate tools and without overrelying on summary metrics (such as MD, PSD, and VFI).29

Blumberg et al28 investigated the associations between 24-2 and 10-2 visual field results and vision-related quality of life measured with the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI VFQ-25). They found that linear models between the 10-2 and NEI VFQ-25 had a stronger association than that of the 10-2 results with 24-2 results. Furthermore, participants with disproportionately low quality of vision relative to their 24-2 visual field damage were more likely to have damage on the central field missed by the 24-2 grid. In another study investigating the association between the NEI VFQ-25 and macular SD-OCT results, Blumberg et al28 found that the characteristic patterns of glaucoma-associated macular RGCP loss appeared to be more important prognosticators of vision-related quality of life than thickness measures, with diffuse RGCP loss as an indicator for diminished vision-related quality of life.

Two of the evaluated staging systems (HPA24 and GVFSS25) take into account the presence of abnormalities within the central 5° or 10° of the 24-2 grid. Therefore, our suggestion that eyes with macular damage (not seen on 24-2 or 30-2 results) should be classified as having severe damage is not necessarily new. The HPA system, for instance, classifies eyes with MD better than −6 dB as severe, if damage is seen within the central 5° of the 24-2 or 30-2 results. Therefore, the message that eyes with structural and functional abnormalities in the macular region should be seen as having severe functional loss is supported by the underlying premises of existing staging systems. Nonetheless, when those systems were developed, high-resolution OCT imaging of the macula was not available; in addition, 10-2 tests were reserved for eyes with severe visual field loss or damage close to fixation. In both the HPA and GVFSS systems, the presence of such abnormalities changes the classification to a more severe stage, most likely because the authors considered that loss of central function had an important role in vision-related quality of life. (Note that, for simplicity, we focused our analyses on the VFI component of the GVFSS system; when all 3 components were analyzed however, this system missed 14% of all macular damage, a small proportion than the other 2 systems.) Nonetheless, the use of visual field tests with 6 × 6° grids (ie, 30-2 and 24-2) often underestimated the presence and extent of damage in the central 10° of the visual field owing to poor sampling (only 12 of the 76 or 54 points, respectively). If 10-2 visual fields (or grids with finer spacing in the central area) are used to define central loss, these systems would classify more eyes as having severe glaucoma. One of the reasons this may not have been done is that for a long time it has been thought that glaucoma does not affect the central field until the later stages of the disease; thus, 10-2 testing was reserved for advanced cases or those with threat to fixation. In recent years, this misconception has been challenged by investigators who used different methods to reach very similar conclusions.7,9,10,13,14,15,30 Another important reason is the more recent implementation of SD-OCT for glaucoma diagnosis and monitoring. High-resolution imaging of the macula has allowed the visualization of the RGCP layer, where glaucomatous damage occurs. Therefore, the old clinical paradigm for glaucoma care, which was based on disc photography, 30-2 or 24-2 visual fields,29 is inadequate not only to diagnose glaucoma but also to determine its severity and effect on quality of life. Added to that, clinicians still tend to overrely on summary metrics not only derived from visual fields (eg, MD, PSD, and VFI) but also from high-resolution SD-OCT images. Test-retest visual field metrics are more variable than OCT metrics and are more influenced by disease severity.31,32 This suboptimal use of SD-OCT imaging often leads to missed macular damage, which can range from 36% to 77% depending on the metric used (eg, quadrants or clock hours).16

The implications for these findings may extend beyond estimating the level of macular damage in patients with or suspected glaucoma, to the quality of care delivered to these patients. As of today, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes are based on 6 × 6° visual field patterns with little information on how central damage is defined (a vague statement of “presence of damage within the central 5°” is provided). This limited approach may affect not only billing and reimbursement, but most importantly how frequently these patients are seen and tested in clinical practice. The present study aimed to underscore 2 main limitations of existing staging systems for glaucoma. First, by using 24-2 (or 30-2) visual fields alone (without a structural test for corroboration), one may have an inadequate assessment of the presence, location, and extent of glaucomatous damage. With the incorporation of high-resolution OCT imaging of the disc and macula, better estimates can be derived when these 2 techniques show topographic agreement. Second, 24-2 and 30-2 visual fields (which serve as basis for existing staging systems) can miss macular damage. This type of central functional loss has substantial implications on vision-related quality of life33 and, as already proposed in the HPA system,24 is sufficient to move the staging level to severe regardless of their MD value.

Consider a patient with macular damage on 10-2 and OCT macular scans, but staged as without damage or with early damage, as in eFigure 3 in the Supplement. At least 2 scenarios are possible for this patient at present: (1) the patient is deemed as having no visual field defect, not treated, and/or seen once a year (or less frequently) or (2) the patient is deemed to have early damage and seen twice a year and tested with 24-2 and/or SD-OCT of the optic disc only. In both scenarios, suboptimal care is being delivered, and the likelihood of progression to blindness or visual impairment is substantially underestimated.

Limitations

Given the specific characteristics of our study sample, clinicians should be cautious about extrapolating results to a broader sample undergoing a different testing paradigm. In addition, obtaining 10-2 visuals fields in all patients may be challenging in clinical practice.

Conclusions

Given the new tools and knowledge on how to define glaucoma and the presence of macular damage, how would we develop a staging system today? Although a detailed classification system would require more debate, if these results are confirmed and generalizable to other patients, we propose that the results of at least a 10-2 visual field (or an alternative with a finer central grid) and macular SD-OCT scans should be included. The implementation of such new systems should be considered by clinicians, researchers, and public health authorities.

eTable. The Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson criteria.

eFigure 1. Examples of normal, early, moderate, and severe visual field defects based upon the Glaucoma Visual Field Staging System.

eFigure 2. The Brusini Glaucoma Staging System 2 chart.

eFigure 3. Examples of eyes in which macular damage was missed by each of the staging systems.

References

- 1.Weinreb RN, Khaw PT. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet. 2004;363(9422):1711-1720. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16257-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miglior S, Pfeiffer N, Torri V, Zeyen T, Cunha-Vaz J, Adamsons I; European Glaucoma Prevention Study (EGPS) Group . Predictive factors for open-angle glaucoma among patients with ocular hypertension in the European Glaucoma Prevention Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(1):3-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):714-720. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Dong L, Yang Z; EMGT Group . Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(11):1965-1972. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Lichter PR, Niziol LM, Janz NK; CIGTS Study Investigators . Visual field progression in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study the impact of treatment and other baseline factors. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(2):200-207. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The AGIS Investigators The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7, the relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):429-440. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00538-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Moraes CG, Hood DC, Thenappan A, et al. 24-2 visual fields miss central defects shown on 10-2 tests in glaucoma suspects, ocular hypertensives, and early glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(10):1449-1456. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grillo LM, Wang DL, Ramachandran R, et al. The 24-2 visual field test misses central macular damage confirmed by the 10-2 visual field test and optical coherence tomography. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2016;5(2):15. doi: 10.1167/tvst.5.2.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park HY, Hwang BE, Shin HY, Park CK. Clinical clues to predict the presence of parafoveal scotoma on Humphrey 10-2 visual field using a Humphrey 24-2 visual field. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;161:150-159. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan-Mee M, Karin Tran MT, Pensyl D, Tsan G, Katiyar S. Prevalence, features, and severity of glaucomatous visual field loss measured with the 10-2 achromatic threshold visual field test. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;168:40-51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hood DC, Raza AS, de Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Glaucomatous damage of the macula. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013;32:1-21. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood DC, Raza AS, de Moraes CG, et al. Initial arcuate defects within the central 10 degrees in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(2):940-946. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langerhorst CT, Carenini LL, Bakker D, De Bie-Raakman MAC. Measurements for Description of Very Early Glaucomatous Field Defects: Perimetry Update. New York, NY: Kugler Publications; 1997:67-73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiefer U, Papageorgiou E, Sample PA, et al. Spatial pattern of glaucomatous visual field loss obtained with regionally condensed stimulus arrangements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(11):5685-5689. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberti G, Manni G, Riva I, et al. Detection of central visual field defects in early glaucomatous eyes: comparison of Humphrey and Octopus perimetry. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang DL, Raza AS, de Moraes CG, et al. Central glaucomatous damage of the macula can be overlooked by conventional OCT retinal nerve fiber layer thickness analyses. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2015;4(6):4. doi: 10.1167/tvst.4.6.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hood DC, De Cuir N, Blumberg DM, et al. A single wide-field OCT protocol can provide compelling information for the diagnosis of early glaucoma. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2016;5(6):4. doi: 10.1167/tvst.5.6.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hood DC, Raza AS. On improving the use of OCT imaging for detecting glaucomatous damage. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(suppl 2):ii1-ii9. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hood DC. Improving our understanding, and detection, of glaucomatous damage: an approach based upon optical coherence tomography (OCT). Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;57:46-75. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YK, Ha A, Na KI, Kim HJ, Jeoung JW, Park KH. Temporal relation between macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer loss and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer loss in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(7):1056-1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parrish RK II, Gedde SJ, Scott IU, et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(11):1447-1455. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160617016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKean-Cowdin R, Varma R, Wu J, Hays RD, Azen SP; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group . Severity of visual field loss and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(6):1013-1023. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brusini P, Johnson CA. Staging functional damage in glaucoma: review of different classification methods. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(2):156-179. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodapp E, Parrish IIR, Anderson D. Clinical Decisions in Glaucoma. St Louis, MO: Mosby Co; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Susanna R Jr, Vessani RM. Staging glaucoma patient: why and how? Open Ophthalmol J. 2009;3:59-64. doi: 10.2174/1874364100903010059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bengtsson B, Heijl A. A visual field index for calculation of glaucoma rate of progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(2):343-353. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brusini P, Filacorda S. Enhanced glaucoma staging system (GSS 2) for classifying functional damage in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2006;15(1):40-46. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000195932.48288.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blumberg DM, De Moraes CG, Prager AJ, et al. Association between undetected 10-2 visual field damage and vision-related quality of life in patients with glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):742-747. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hood DC, De Moraes CG. Challenges to the common clinical paradigm for diagnosis of glaucomatous damage with oct and visual fields. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(2):788-791. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traynis I, De Moraes CG, Raza AS, Liebmann JM, Ritch R, Hood DC. Prevalence and nature of early glaucomatous defects in the central 10° of the visual field. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):291-297. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.7656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artes PH, Hutchison DM, Nicolela MT, LeBlanc RP, Chauhan BC. Threshold and variability properties of matrix frequency-doubling technology and standard automated perimetry in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(7):2451-2457. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abadia B, Ferreras A, Calvo P, Fogagnolo P, Figus M, Pajarin AB. Effect of the eye tracking system on the reproducibility of measurements obtained with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(7):638-645. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garg A, Hood DC, Pensec N, Liebmann JM, Blumberg DM. Macular damage, as determined by structure-function staging, is associated with worse vision-related quality of life in early glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;S0002-9394(18)30392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. The Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson criteria.

eFigure 1. Examples of normal, early, moderate, and severe visual field defects based upon the Glaucoma Visual Field Staging System.

eFigure 2. The Brusini Glaucoma Staging System 2 chart.

eFigure 3. Examples of eyes in which macular damage was missed by each of the staging systems.