Key Points

Questions

What is the rate of research biopsy reporting for clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, and what clinical trial factors correlate with research biopsy reporting?

Findings

In this study, only 50.8% of trials that included a research biopsy–related end point reported on these biopsies. The percentage of conducted mandatory biopsies increased significantly over time, and these biopsies were also more likely to be reported in ClinicalTrials.gov and publications.

Meaning

Improved efforts are needed by sponsors and investigators to report results obtained from research biopsies.

Abstract

Importance

Research biopsies are frequently incorporated within clinical trials in oncology and are often a mandatory requirement for trial enrollment. However, limited information is available regarding the extent and completeness of research biopsy reporting.

Objectives

To determine the rate of research biopsy reporting for clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov and determine the clinical trial factors that correlated with research biopsy reporting.

Design, Setting, and Participants

ClinicalTrials.gov (CTG) was searched for all oncologic therapeutic clinical trials with completion dates between January 1, 2000, and January 1, 2015, with end point category terms including biopsy, biopsies, or tissue. The date of the final publication search was March 12, 2018. Trials conducting only diagnostic biopsies or trials using bone marrow biopsies or liquid biopsies were excluded. Credit for biopsy reporting was given for any mention of performing or results from tissue biopsies in publications. Clinical trials were compared with the highest level of corresponding publication or registry report. Fisher exact test was used for analysis.

Results

A total of 301 clinical trials were identified, with a median of 37 patients (range, 1-1310 patients) enrolled per trial. After a median follow-up time of 5.8 years from trial completion, 244 of 301 trials (81.1%) reported results: publications in 195 (64.8%) and CTG registry in 49 (16.3%). Reporting of trial results was associated with later-stage trials (phase 2/3) (137 of 153 [89.5%] for phase 2/3 vs 107 of 148 [72.3%] for phase 1 or 1/2 trials; P < .001). Results from research biopsies were reported in 153 of 301 (50.8%) trials or in 153 of 244 (62.7%) trials with published results. Rates varied by type of presentation: 142 of 195 publications (72.8%) vs 11 of 49 CTG reports (22.4%) (P < .001). Conducting mandatory biopsies (82.1% [101 of 123] vs 43.0% [52 of 121]; P < .001), early-phase clinical trials (70.1% [75 of 107] vs 56.9% [78 of 137]; P = .03), and listing the biopsy as a primary objective in CTG (76.3% [45 of 59] vs 58.4% [108 of 185]; P = .01) was associated with improved biopsy reporting. Trials that met their primary end point (71.9% [115 of 160] vs 45.2% [38 of 84]; P < .001) and those published in higher-impact journals (81.1% [77 of 95] vs 65.0% [65 of 100]; P = .01) had improved biopsy reporting. Mandatory biopsies and biopsy reporting increased over time with similar slopes (P = .58).

Conclusions and Relevance

Despite ethical obligations to report research biopsies, only 50.8% of all trials that included a research biopsy–related end point in CTG reported on these biopsy-related results. Improved efforts are needed to report results obtained from research biopsies.

This study searched ClinicalTrials.gov to examine the reporting rates of research biopsies conducted in oncology clinical trials amd investigates what factors correlate with research biopsy reporting.

Introduction

The need to characterize the tumor and its microenvironment has led to the increased use of research biopsies to obtain tumor tissue for correlative science.1,2 As the use of research biopsies becomes more entrenched, there is a critical need to ensure transparent reporting of results obtained from such biopsies. In clinical trial research, a procedure with individual patient risk is justifiable based on the expectation that generalizable knowledge will be gained. In a recent study by Parseghian et al,3 a single-institution cohort demonstrated that 39% of clinical trials that included research biopsies reported results from such biopsies. To determine the generalizability of these findings, this study evaluates research biopsy reporting in a large clinical trial database.

Methods

Identification of Trials

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov (CTG) for all oncologic investigational studies with completion dates from January 1, 2000, to January 1, 2015. Search terms included biopsy, biopsies, tumor tissue, tissue, and cancer. Only trials conducting solid organ or lymph node research biopsies were included. Trials conducting only diagnostic biopsies, bone-marrow biopsies, or liquid biopsies were excluded. A total of 301 therapeutic clinical trials were ultimately analyzed. Trial and research biopsy characteristics were categorized according to documentation in CTG. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval by the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center because only publicly available data were used.

Evaluation of Biopsy Reporting

Biopsy reporting was defined as either the mentioning of biopsies having been performed or the analysis of biopsy-collected tumor tissue in any part of a published report or registry. The publication status for each trial in CTG was assessed by PubMed and Google Scholar searches using the investigators’ names, part or all of the trial title, and various key words. If a publication was not identified, an evaluation for online reporting in CTG and pharmaceutical company registries was conducted. The date of the final publication search was March 12, 2018. Final reporting was defined by either a publication or CTG listing.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used to investigate factors associated with biopsy reporting. Linear regression was used to assess the association between year of trial completion and the rate of mandatory biopsy and biopsy reporting. The Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify the trend of mandatory biopsy inclusion over time. A 2-sided t test was used to assess for a difference between the slopes of inclusion of mandatory biopsies and biopsy reporting. A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered significant. The primary end point of this study was rate of clinical trial research biopsy reporting in a publication or registry. Secondary end points included the identification of factors associated with research biopsy reporting. Statistical analysis was conducted with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute).

Results

Clinical Trial Characteristics

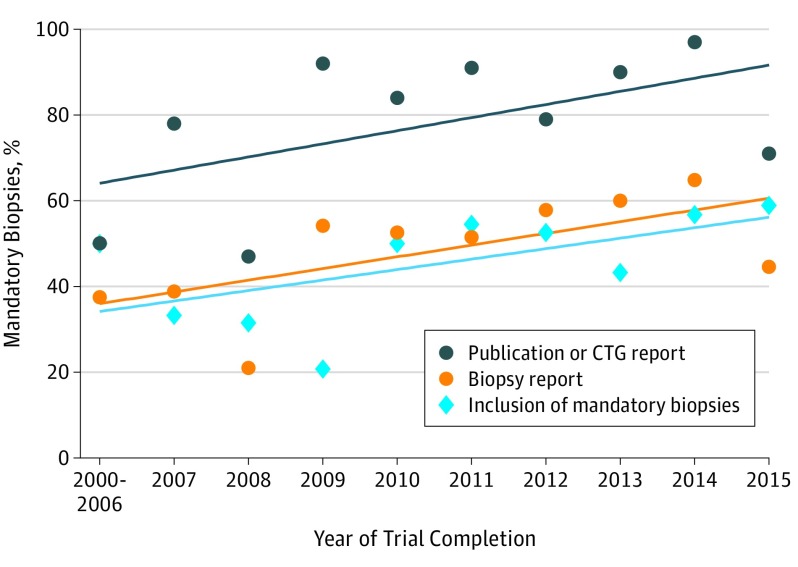

Characteristics of the 301 clinical trials are listed in the Table. A median of 37 partients (range, 1-1310 patients) were enrolled per trial. Nearly half of all trials performed mandatory biopsies, 145 of 301 (48.2%), and the rate of inclusion of mandatory biopsies increased steadily over the years included in this analysis (P = .001) (Figure). Only 86 of 301 trials (28.6%) conducted serial biopsies, and a research biopsy was listed as a primary objective in CTG in 72 of 301 trials (23.9%).

Table. Clinical Trial Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Final Reports | Biopsy Reporting in Final Reports | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Published Results, No. (%) | P Value | No. | Biopsy Results, No. (%) | P Value | |

| Clinical trial | 301 | 244 (81.1) | 244 | 153 (62.7) | ||

| Type of biopsy | ||||||

| Mandatory | 145 | 123 (84.8) | .14 | 123 | 101 (82.1) | <.001 |

| Optional | 156 | 121 (77.6) | 121 | 52 (43.0) | ||

| Serial biopsies | ||||||

| Yes | 86 | 72 (83.7) | .51 | 72 | 51 (70.8) | .11 |

| No | 215 | 172 (80.0) | 172 | 102 (59.3) | ||

| Study sponsorship | ||||||

| Academic | 191 | 160 (83.8) | .12 | 160 | 103 (64.4) | .48 |

| Industry | 110 | 84 (76.4) | 84 | 50 (59.5) | ||

| Participants enrolled, No. | ||||||

| ≤35 | 147 | 117 (79.6) | .56 | 117 | 70 (59.8) | .42 |

| >35 | 154 | 127 (82.5) | 127 | 83 (65.4) | ||

| Phase of clinical trial | ||||||

| 1 or 1/2 | 148 | 107 (72.3) | <.001 | 107 | 75 (70.1) | .03 |

| 2 or 3 | 153 | 137 (89.5) | 137 | 78 (56.9) | ||

| Biopsy listed as primary objective in ClinicalTrials.gov | ||||||

| Yes | 72 | 59 (81.9) | .49 | 59 | 45 (76.3) | .01 |

| No | 229 | 185 (80.8) | 185 | 108 (58.4) | ||

| Primary objective of clinical trial meta | ||||||

| Yes | NA | NA | NA | 160 | 115 (71.9) | <.001 |

| No | NA | NA | NA | 84 | 38 (45.2) | |

| Journal impact factorb | ||||||

| <7 | NA | NA | NA | 100 | 65 (65.0) | .01 |

| ≥7 | NA | NA | NA | 95 | 77 (81.1) | |

| Tumor type | ||||||

| Various solid tumors | 63 | 53 (84.1) | 53 | 32 (60.4) | ||

| Thoracic | 47 | 34 (72.3) | 34 | 24 (70.6) | ||

| Colorectal | 32 | 25 (78.1) | 25 | 15 (60.0) | ||

| Melanoma | 25 | 25 (100) | 25 | 11 (44.0) | ||

| Other | 134 | 107 (80.0) | 107 | 71 (66.4) | ||

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

For trials that were published in either manuscript or registry (n = 244).

For trials that were published in manuscript (n = 195).

Figure. Rate of Publication, ClinicalTrials.gov Reporting, and Inclusion of Mandatory Biopsies Over Time.

The rate of publication or ClinicalTrials.gov (CTG) presentation and biopsy reporting both increased significantly over time. The rate of inclusion of mandatory biopsies increased steadily over the years included in this analysis (P = .001). The slope of the increase in biopsy reporting was no different than the slope of the increase in mandatory biopsies over time (2.44 vs 3.41; P = .58).

Factors Correlating With Research Biopsy Reporting and Publication

After a median follow-up of 5.8 years (range, 3.17-15.5 years) from trial completion (≥4 years in 218 of 301 trials [72.4%]), 195 of 301 trials (64.8%) had published the findings, 49 (16.3%) had reported results in CTG, and 57 (18.9%) were not reported in either of these, nor did they appear in pharmaceutical or international registries.

Research biopsies were reported in 153 of all 301 trials (50.8%) and 153 of 244 reported trials (62.7%). Research biopsy reporting differed by location, with 142 of 195 publications (72.8%) reporting biopsies, while 11 of 49 trials listed in CTG (22.4%) reported biopsies (P < .001) (Table).

The conduct of mandatory biopsies correlated with biopsy reporting in both publications (82.1% [101 of 123] vs 43.0% [52 of 121]; P < .001), and CTG (45.0% vs 6.9%; P = .004). Phase 1 or 1/2 clinical trials (70.1% [75 of 107] vs 56.9% [78 of 137]; P = .004), and listing a biopsy as a primary objective in CTG also correlated with biopsy reporting (76.3% [45 of 59] vs 58.4% [108 of 185]; P = .01). Biopsy reporting also correlated with trials that met their primary end point (71.9% [115 of 160] vs 45.2% [38 of 84]; P < .001) and trials published in journals with higher impact factor (65.0% [65 of 100] vs 81.1% [77 of 95]; P = .01). Although publication did not correlate with trial sponsorship, academic sponsorship correlated with biopsy reporting in manuscripts (78.0% vs 63.2%; P = .04).

The rate of publication or CTG listing and of biopsy reporting both increased over time. Mandatory biopsies and biopsy reporting increased over time with similar slopes (P = .58) (Figure). The only factor that correlated with clinical trial reporting was phase 2 or 3 studies in comparison with phase 1 or 1/2 studies (72.3% [107 of 148] vs 89.5% [137 of 153]; P < .001) (Table).

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of a large clinical trial registry suggests that only 153 of 301 (50.8%) of clinical trials report research biopsies. In addition, reporting was significantly less for clinical trials in which results were reported only in a registry (11 of 49 [22.4%]) vs manuscript publications (142 of 195 [72.8%]). The factors that correlated with clinical trial reporting differed from those that correlated with research biopsy reporting, suggesting the need for varied approaches to improve both clinical trial and research biopsy reporting.

Prior investigations have found that a high rate of clinical trials in oncology remain unpublished.3,4,5,6,7,8 Due to these findings, recent regulations have been enacted to require clinical trial result reporting.9 However, these efforts are limited to outcome measures that are part of a clinical trial’s statistical analysis plan, and thus are unlikely to include most research biopsies.10 Our finding that only 11 of 49 (22.4%) of trials that conducted research biopsies reported on the conduct of these biopsies when listed in CTG supports this concern.

One of the major findings of this study was the identification of factors that correlate with improved reporting of research biopsies. In particular, we found that the percentage of conducted mandatory biopsies increased significantly over time, and that these biopsies were also more likely to be reported in CTG and publications. Although all research biopsies should be reported for transparency, these data suggest that optional biopsies may be leading to insufficient evidence to answer a scientific question, and hence, are not being reported. Alternatively, researchers may feel more ethically inclined to report mandatory biopsies. In addition, the listing of a biopsy as a primary objective in CTG correlated with improved research biopsy reporting. Both of these findings reflect the integral incorporation of research biopsies into a clinical trial and provide guidance to investigators that scientifically rigorous integration of research biopsies into clinical trials may lead to improved final reporting.

Limitations

There are limitations to the study. Despite the large number of clinical trials evaluated, this work represents the findings from a single registry regarding the planned conduct of research biopsies. There is likely selection bias regarding the trials that reported results. We relied on trials that were indicated in CTG as being completed to ensure adequate time to publication (median, 5.8 years from trial completion to this analysis and ≥3 years in 100% of trials). Prior studies evaluating time from clinical trial completion until publication have reported a median time of 21 to 25 months (interquartile range, 13-37 months).11,12 The number of biopsies ultimately performed within each trial could not be determined.

Conclusions

In this era of molecular medicine, there has been an increased demand for fresh tumor tissue in clinical trials for purposes of proof-of-concept biomarker development, understanding of resistance mechanisms, and evaluating response.2 Using CTG—a large, public clinical trial database—our results suggest that many research biopsies are unreported. Increased efforts are needed to improve the reporting of research biopsies, not only as an ethical duty to patients, but also for the benefit of the scientific community.

References

- 1.Banerji U, de Bono J, Judson I, Kaye S, Workman P. Biomarkers in early clinical trials: the committed and the skeptics. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(8):2512. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goulart BH, Clark JW, Pien HH, Roberts TG, Finkelstein SN, Chabner BA. Trends in the use and role of biomarkers in phase I oncology trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(22 Pt 1):6719-6726. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parseghian CM, Raghav K, Wolff RA, et al. Underreporting of research biopsies from clinical trials in oncology. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(21):6450-6457. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krzyzanowska MK, Pintilie M, Tannock IF. Factors associated with failure to publish large randomized trials presented at an oncology meeting. JAMA. 2003;290(4):495-501. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.4.495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bellefeuille C, Morrison CA, Tannock IF. The fate of abstracts submitted to a cancer meeting: factors which influence presentation and subsequent publication. Ann Oncol. 1992;3(3):187-191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeg RT, Lee JA, Mathiason MA, et al. Publication outcomes of phase II oncology clinical trials. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(3):253-257. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181845544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camacho LH, Bacik J, Cheung A, Spriggs DR. Presentation and subsequent publication rates of phase I oncology clinical trials. Cancer. 2005;104(7):1497-1504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massey PR, Wang R, Prasad V, Bates SE, Fojo T. Assessing the eventual publication of clinical trial abstracts submitted to a large annual oncology meeting. Oncologist. 2016;21(3):261-268. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Carr S. Trial reporting in ClinicalTrials.gov—the final rule. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(20):1998-2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1611785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overman MJ, Modak J, Kopetz S, et al. Use of research biopsies in clinical trials: are risks and benefits adequately discussed? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):17-22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YP, Liu X, Lv JW, et al. Publication status of contemporary oncology randomised controlled trials worldwide. Eur J Cancer. 2016;66:17-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross JS, Mocanu M, Lampropulos JF, Tse T, Krumholz HM. Time to publication among completed clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):825-828. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]