This national survey study of patients with cancer evaluates the association between patient comorbid conditions and cancer clinical trial participation.

Key Points

Question

Is the presence of comorbidities in patients with cancer associated with the decision-making process for participation in cancer clinical trials?

Findings

This study uses data from a national survey of 5499 patients with cancer and finds that an increase in comorbidities was associated with significantly reduced trial discussions, trial offers, and trial participation itself. Simulation analyses suggest that modernizing eligibility criteria could generate many additional patient trial registrations annually.

Meaning

Independent of sociodemographic variables, the presence of comorbidities adversely influences clinical trial decision-making; modernizing comorbidity-related eligibility criteria could provide an opportunity for several thousand more patients with well-managed comorbidities to participate in trials each year.

Abstract

Importance

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Friends of Cancer Research, and the US Food and Drug Administration recently recommended modernizing criteria related to comorbidities routinely used to exclude patients from cancer clinical trials. The goal was to design clinical trial eligibility such that trial results better reflect real-world cancer patient populations, to improve clinical trial participation, and to increase patient access to new treatments in trials. Yet despite the assumed influence of comorbidities on trial participation, the relationship between patients’ comorbidity profile at diagnosis and trial participation has not been explicitly examined using patient-level data.

Objectives

To investigate the association between comorbidities, clinical trial decision-making, and clinical trial participation; and to estimate the potential impact of reducing comorbidity exclusion criteria on trial participation, to provide a benchmark for changing criteria.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A national survey was embedded within a web-based cancer treatment-decision tool accessible on multiple cancer-oriented websites. Participants must have received a diagnosis of breast, lung, colorectal, or prostate cancer. In total, 5499 surveyed patients who made a treatment decision within the past 3 months were analyzed using logistic regression analysis and simulations.

Exposures

Cancer diagnosis and 1 or more of 18 comorbidities.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patient discussion of a clinical trial with their physician (yes vs no); if a trial was discussed, the offer of trial participation (yes vs no); and, if trial participation was offered, trial participation (yes vs no).

Results

Of the 5499 patients who participated in the survey, 3420 (62.6%) were women and 2079 (37.8%) were men (mean [SD] age, 56.63 [10.05] years). Most patients (65.6%; n = 3610) had 1 or more comorbidities. The most common comorbid condition was hypertension (35.0%; n = 1924). Compared with the absence of comorbidities, the presence of 1 or more comorbidities was associated with a decreased risk of trial discussions (44.1% vs 37.2%; OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.97; P = .02), trial offers (21.7% vs 15.7%; OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.96; P = .02), and trial participation (11.3% vs 7.8%; OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.94; P = .01). The removal of the ASCO-recommended comorbidity restrictions could generate up to 6317 additional patient trial registrations every year.

Conclusions and Relevance

Independent of sociodemographic variables, the presence of comorbidities is adversely associated with trial discussions, trial offers, and trial participation itself. Updating trial eligibility criteria could provide an opportunity for several thousand more patients with well-managed comorbidities to participate in clinical trials each year.

Introduction

The successful conduct of cancer clinical trials is made possible by the willing participation of patients with cancer. However, it is estimated that 5% or fewer patients with cancer participate in trials.1,2,3 Institutional factors play the largest role, with lack of a locally available trial excluding half of all patients from trial participation. Not surprisingly, large academic centers with broad trial offerings enroll patients at nearly twice the rate of community-based centers.4 Patient barriers include fear of randomization, the desire to determine their own treatment, and cost concerns. Barriers may also differ by demographic variables; the especially low rate of older patients in trials is typically ascribed to their poorer clinical status.4,5,6,7,8,9 While structural barriers are greater, clinical trial eligibility barriers are potentially more mutable and could result in increased trial participation even if other barriers remain unchanged. At least 60% of trial eligibility exclusions pertain to patient comorbidities or performance status.10 Some amount of selection bias in trials related to comorbidities is inevitable to maintain patient safety,11,12 but modernizing trial eligibility criteria could expand access to trials and speed their conduct.

Recently, stakeholders from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Friends of Cancer Research, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established working groups to examine whether common eligibility criteria for trials could safely be modified.13 The goal was to design cancer clinical trial eligibility such that trial results better reflect real-world patient populations, to improve clinical trial participation, and to increase patient access to new treatments in trials.14 They recommended the modernization of certain criteria routinely used to exclude patients from trials, including the presence of brain metastases, age limits, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, organ dysfunction, and prior cancer.15 Despite the assumed influence of comorbidities on trial participation, the relationship between patient health status and trial decision-making outcomes (including trial discussions, trial offers, and trial participation) has not been explicitly examined using patient-level data. This is likely because comorbidity data have rarely been collected in the context of studies of trial participation.

In this study, we use data from a large, national, web-based survey of cancer patients to examine the relationship between comorbidities, clinical trial decision-making and trial participation. We also modeled the potential impact of reducing major comorbidity exclusion criteria in trials, to provide a benchmark for evaluation of the impact of the ASCO recommendations.

Methods

We used data from a large, national survey to examine the patient decision-making process about participation in a clinical treatment trial among patients with a first diagnosis of breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer.16 As previously described, the survey was embedded online within a web-based cancer treatment decision tool that was accessible on multiple cancer-oriented websites (eg, American Cancer Society); 77 752 surveys were auto-generated for new registrants, and 6259 respondents agreed to participate. Three months after registration to the treatment decision tool, patients who agreed to participate were surveyed about their demographics, staging, and comorbidities, as well as their treatment decision-making process with respect to clinical trial participation. The study was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval and written informed consent because we collected no individual patient identifiers.

Comorbidities

The survey collected comorbidity data on 18 separate conditions based on the Charlson comorbidity index (eTable 1 in the Supplement).17 Survey respondents were asked whether they currently have or previously had 1 or more of the comorbidities. Allowed responses were “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know.” For each condition, fewer than 0.5% of responses were “don’t know” with the exception of degenerative joint disease (1.25%). For the analysis, the “don’t know” responses were coded as “no.”

End Points

Patients were also surveyed about their treatment decision-making process. Patients were presented with a definition of a clinical trial (eQuestions in the Supplement). Patients were then asked whether they had discussed trial participation with their physician; options for response included “no,” “yes, but not offered participation in a clinical trial,” and “yes, and was offered participation in a clinical trial.” If a trial was offered, patients were asked whether they had accepted or declined participation. For this analysis, the end points were defined as whether a trial was discussed with a patient (yes vs no), whether a trial was offered to a patient (yes vs no), and whether the patient participated in a trial (yes vs no).

Covariates

The association between comorbidities and outcomes was also considered in the context of age (<65 vs ≥65 years), sex, college education, race (African American vs white/other), patient-reported yearly household income (<$50 000 vs ≥$50 000) and cancer type.

Statistical Methods

Our goal was to examine the association between the 18 comorbidities, alone or in combination, and treatment decision-making outcomes—trial discussion, trial offer, and trial participation. Univariate associations of each condition and the 3 outcomes were examined. We then examined the association between 0 vs 1 or more comorbidities and each outcome, in both the univariate and multivariable settings. Analyses were conducted using logistic regression.

In a more refined analysis, we identified a subset of comorbidities that best predicted outcomes. To limit the number of covariates for multivariable modeling, we included only those conditions with a statistically significant (P < .05) univariate association with each outcome. We used the method of best subsets—a regression technique—to identify those comorbidities that collectively best predicted outcomes.18 The best subset method tests all possible combinations of the candidate covariates and identifies the combination of k covariates that achieves the best fit based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). From the k variables, we calculated a comorbidity risk score by summing the number of adverse comorbidity factors for each patient. The adverse risk scores for trial discussion, trial offer, and trial participation were then evaluated for their capability to predict outcomes in both the univariate setting (adverse risk score only) and multivariable setting (adjusting for demographic factors, income, and cancer type).

These analyses were conducted to establish whether risk models in which comorbidities could independently predict trial treatment decision-making outcomes could feasibly be built. To that end, 2-sided tests with alpha = 0.05 were used without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

We then examined how the overall trial participation rate would change if patients with major comorbidities participated in trials at the same rate as patients without major comorbidities. This analysis was intended to simulate how removing ASCO-recommended comorbidity exclusion criteria—that is, conditions identified and prioritized by ASCO, Friends of Cancer Research, and the FDA for development of recommendations for broadening trial eligibility criteria—would affect trial eligibility rates. These comorbidity categories included, individually, (1) hepatic dysfunction (cirrhosis), (2) renal dysfunction, (3) cardiovascular disease (eg, heart attack, heart failure, bypass surgery, stroke or transient ischemic attack, blood clots), and (4) prior cancer as well as 1 or more of these 4 categories.19 For each category, we calculated the overall trial participation rate, assuming that patients with a given condition participated in trials at the same rate as patients with no comorbidities. We then added the additional trial participants assumed to participate under the counterfactual scenario to the original number of participants to derive a simulated participation rate across all respondents. Lung dysfunction, based on the presence of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (including also emphysema and chronic bronchitis), was not a separate category in ASCO’s framework but was examined separately.

Finally, we estimated the overall trial participation rate assuming that trials had no eligibility exclusions for any of the major comorbidities at all. In this last analysis, we did not account for exclusions due to hearing or vision loss, which are not typically considered exclusion criteria for cancer trials. Rates were adjusted for age and race to account for potential differences in the distribution of these patients in this cohort.

Results

In total, 5499 participants (87.9% of the 6259 who agreed to participate) had made a treatment decision within the past 3 months and were surveyed about their decision-making process about trial participation. Participants were primarily younger than 65 years (78.2%; n = 4300), female (62.2%; n = 3420), and white (94.4%; n = 5192; eTable 2 in the Supplement). The most common cancer types were breast (52.6%; n = 2894) and prostate (28.1%; n = 1546).

Comorbid Disease Conditions

As detailed in Table 1, the most prevalent disease condition was hypertension (35.0%; n = 1924). Other common disease conditions (ie, ≥10% incidence in the cohort) were vision loss (16.6%; n = 912), arthritis (15.3%; n = 841), asthma (11.5%; n = 630), hearing loss (11.2%; n = 613), and previous cancer (10.2%; n = 559). Cardiac conditions were more rare, including bypass surgery (1.8%; n = 100), heart attack (3.4%; n = 189), and heart failure (1.2%; n = 63). Sixty-six percent of patients (n = 3610) had 1 or more comorbidities. The prevalence of common disease conditions in the study cohort was generally representative of the US population with a similar age distribution (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Patient Comorbidities.

| Comorbid Conditiona | Category | No. (%; 95%

CI) (n = 5499)b |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular (any) | Blood clots | 275 (5.0; 4.4-5.6) |

| Bypass surgery | 100 (1.8; 1.5-2.2) | |

| Heart attack | 189 (3.4; 3.0-4.0) | |

| Heart failure | 63 (1.2; 0.9-1.5) | |

| Hypertension | 1924 (35.0; 33.7-36.3) | |

| Stroke/TIA | 124 (2.3; 1.9-2.7) | |

| Kidney disease | … | 94 (1.7; 1.4-2.1) |

| Liver (cirrhosis) | … | 29 (0.5; 0.4-0.8) |

| Lung (any) | Asthma | 630 (11.5; 10.6-12.3) |

| COPD | 364 (6.6; 6.0-7.3) | |

| Previous cancer | … | 559 (10.2; 9.4-11.0) |

| Other (any) | Alzheimer | 19 (0.4; 0.2-0.5) |

| Arthritis | 841 (15.3; 14.4-16.3) | |

| Diabetes | 436 (7.9; 7.2-8.7) | |

| Hearing loss | 613 (11.2; 10.3-12.0) | |

| Joint disease | 447 (8.1; 7.4-8.9) | |

| Ulcers | 317 (5.8; 5.2-6.4) | |

| Vision loss | 912 (16.6; 15.6-17.6) | |

| Any comorbidity | … | 3610 (65.6; 64.4-66.9) |

| No. of comorbidities | 0 | 1889 (34.4; 33.1-35.6) |

| 1 | 1530 (27.8; 26.6-29.0) | |

| 2 | 983 (17.9; 16.9-18.9) | |

| 3 | 531 (9.7; 8.9-10.5) | |

| 4 | 268 (4.9; 4.3-5.5) | |

| ≥5 | 298 (5.4; 4.8-6.1) |

Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Categories created to align as closely as possible with the ASCO framework.

Based on one sample exact binomial confidence interval.

Association of Individual Disease Conditions and Outcomes

In total, 2174 patients (39.5%) reported discussing a trial with their physician, 978 (17.8%) reported being offered trial participation, and 496 (9.0%) reported participating in a trial. In almost all cases, the presence of a comorbid condition was associated with lower observed rates of trial discussion (16 of 18 instances), trial offer (17 of 18), and trial participation (16 of 18). As supported by data reported in Table 2, the common comorbidities most strongly associated with each of the 3 outcomes included hypertension, prior cancer, and hearing loss. Other factors associated with trial participation were cardiovascular conditions and arthritis. The results of multivariable analyses of these individual disease conditions are detailed in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Univariate Associations of Comorbid Conditions and Trial Discussion, Offer, and Participation.

| Comorbidity | Trial Discussion | Trial Offer | Trial Participation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition? (Yes vs No), %a | OR (95% CI) | P Value | Condition? (Yes vs No), %a | OR (95% CI) | P Value | Condition? (Yes vs No), %a | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Any comorbidity | 37.2 vs 44.1 | 0.75 (0.67-0.84) | <.001 | 15.7 vs 21.7 | 0.67 (0.58-0.78) | <.001 | 7.8 vs 11.3 | 0.66 (0.55-0.80) | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular (any) | |||||||||

| Blood clots | 37.1 vs 39.7 | 0.90 (0.69-1.16) | .41 | 13.1 vs 18.0 | 0.68 (0.46-0.98) | .04 | 8.0 vs 9.1 | 0.87 (0.53-1.37) | .67 |

| Bypass surgery | 28.0 vs 39.7 | 0.59 (0.37-0.93) | .02 | 4.0 vs 18.0 | 0.19 (0.05-0.50) | <.001 | 2.0 vs 9.1 | 0.20 (0.02-0.76) | .008 |

| Heart attack | 36.0 vs 39.7 | 0.86 (0.62-1.17) | .33 | 9.0 vs 18.1 | 0.45 (0.25-0.74) | <.001 | 5.3 vs 9.2 | 0.55 (0.26-1.05) | .07 |

| Heart failure | 28.6 vs 39.7 | 0.61 (0.33-1.08) | .09 | 7.9 vs 17.9 | 0.40 (0.12-0.98) | .05 | 0.0 vs 9.1 | 0.00 (0.00-0.60) | .006 |

| Hypertension | 34.5 vs 42.2 | 0.72 (0.64-0.81) | <.001 | 14.0 vs 19.8 | 0.66 (0.56-0.77) | <.001 | 7.6 vs 9.8 | 0.76 (0.61-0.93) | .007 |

| Stroke/TIA | 32.3 vs 39.7 | 0.72 (0.48-1.07) | .10 | 8.1 vs 18.0 | 0.40 (0.19-0.77) | .003 | 4.0 vs 9.1 | 0.42 (0.13-1.01) | .06 |

| Kidney disease | 29.8 vs 39.7 | 0.64 (0.40-1.02) | .06 | 6.4 vs 18.0 | 0.31 (0.11-0.71) | .002 | 4.3 vs 9.1 | 0.44 (0.12-1.18) | .14 |

| Liver (cirrhosis) | 31.0 vs 39.6 | 0.69 (0.27-1.58) | .45 | 13.8 vs 17.8 | 0.74 (0.19-2.15) | .81 | 10.3 vs 9.0 | 1.16 (0.22-3.82) | .74 |

| Prior cancer | 34.5 vs 40.1 | 0.79 (0.65-0.95) | .01 | 13.4 vs 18.3 | 0.69 (0.53-0.90) | .004 | 5.9 vs 9.4 | 0.61 (0.41-0.88) | .006 |

| Lung (any) | |||||||||

| Asthma | 42.5 vs 39.1 | 1.15 (0.97-1.37) | .11 | 19.0 vs 17.6 | 1.10 (0.88-1.36) | .38 | 9.2 vs 9.0 | 1.03 (0.76-1.37) | .88 |

| COPD | 36.0 vs 39.8 | 0.85 (0.68-1.07) | .17 | 10.4 vs 18.3 | 0.52 (0.36-0.74) | <.001 | 7.7 vs 9.1 | 0.83 (0.54-1.24) | .40 |

| Other (any) | |||||||||

| Alzheimer | 52.6 vs 39.5 | 1.70 (0.62-4.74) | .25 | 5.3 vs 17.8 | 0.26 (0.01-1.63) | .23 | 5.3 vs 9.0 | 0.56 (0.01-3.56) | >.99 |

| Arthritis | 35.2 vs 40.3 | 0.80 (0.69-0.94) | .005 | 13.8 vs 18.5 | 0.70 (0.57-0.87) | <.001 | 6.2 vs 9.5 | 0.63 (0.46-0.84) | .001 |

| Diabetes | 36.0 vs 39.8 | 0.85 (0.69-1.05) | .13 | 12.6 vs 18.2 | 0.65 (0.47-0.87) | .003 | 6.9 vs 9.2 | 0.73 (0.48-1.07) | .12 |

| Hearing loss | 32.6 vs 40.4 | 0.71 (0.59-0.86) | <.001 | 12.2 vs 18.5 | 0.61 (0.47-0.79) | <.001 | 5.4 vs 9.5 | 0.54 (0.37-0.78) | <.001 |

| Joint disease | 38.9 vs 39.6 | 0.97 (0.79-1.19) | .80 | 15.0 vs 18.0 | 0.80 (0.60-1.05) | .12 | 6.0 vs 9.3 | 0.63 (0.40-0.94) | .02 |

| Ulcers | 33.4 vs 39.9 | 0.76 (0.59-0.97) | .02 | 14.5 vs 18.0 | 0.77 (0.55-1.07) | .13 | 6.9 vs 9.1 | 0.74 (0.45-1.16) | .22 |

| Vision loss | 35.3 vs 40.4 | 0.81 (0.69-0.94) | .004 | 14.6 vs 18.4 | 0.76 (0.62-0.92) | .005 | 7.5 vs 9.3 | 0.78 (0.59-1.03) | .08 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Observed rates for presence (yes) vs absence (no) of the given condition.

Association of Comorbidity Summary Measures and Outcomes

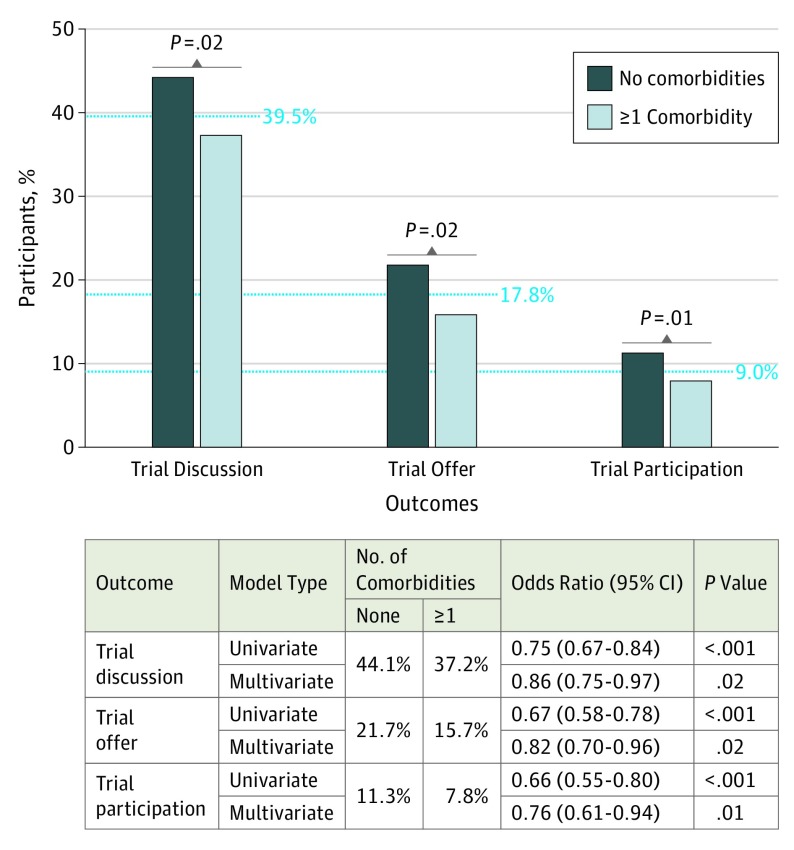

In multivariable logistic regression, the presence of 1 or more comorbidities was associated with a decreased risk of trial discussions (44.1% vs 37.2%; OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.97; P = .02), trial offers (21.7% vs 15.7%; OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.96; P = .02), and trial participation (11.3% vs 7.8%; OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.94; P = .01) and results in the univariate setting were more extreme (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rates of Trial Discussions, Offers, and Participation by Presence of Comorbid Conditions.

P values are derived from univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses adjusted for demographic factors, income, and cancer type.

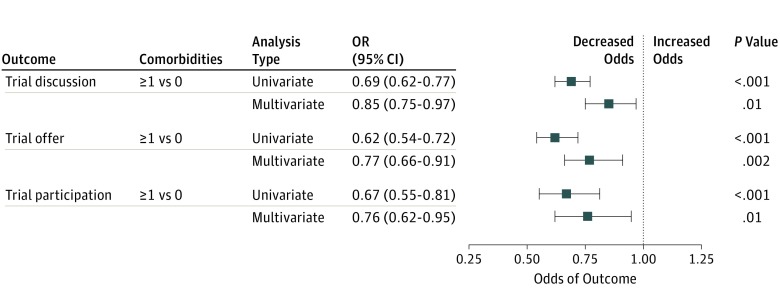

Using the best subsets method, we identified best models that included the following independently predictive variables; hearing loss, prior cancer, hypertension, and bypass surgery (for all 3 outcomes); ulcers (for trial discussions); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney disease, stroke, and arthritis (for trial offers); and arthritis (for trial participation). As supported by the data reported in the eFigure in the Supplement, under almost any categorization of the number of risk factors, an increasing number of comorbidities was associated with poor trial participation outcomes. For consistency across outcomes, we further derived a comorbidity risk score based only on those common comorbidities (hearing loss, prior cancer, and hypertension) that were identified as independently predictive factors in the best model for each individual outcome. In multivariable regression, an increase from 0 to 1 or more comorbidities was associated with a decreased risk of trial discussions (15% lower, P = .01), trial offers (23% lower, P = .002), and trial participation (24% lower, P = .01) (Figure 2). Results were similar if bypass surgery was also included in the risk score.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Association Between Comorbidity Risk Score and Outcomes Using Common Comorbidity Variables.

Hypertension, prior cancer, and hearing loss occurred in at least 10% of patients and were independent predictors of each study outcome. In total, 2948 participants (53.6%) had 0 comorbidities, and 2551 (46.4%) had 1 or more comorbidities. For each analysis, the blue box represents the odds ratio and the horizontal line represents the 95% confidence interval (CI). Multivariate logistic regression analyses included covariate adjustment for demographic factors and income, and were stratified by cancer type. Results were similar if bypass surgery (frequency, 1.8%) was included (data not shown). OR indicates odds ratio.

Simulated Trial Participation Rates

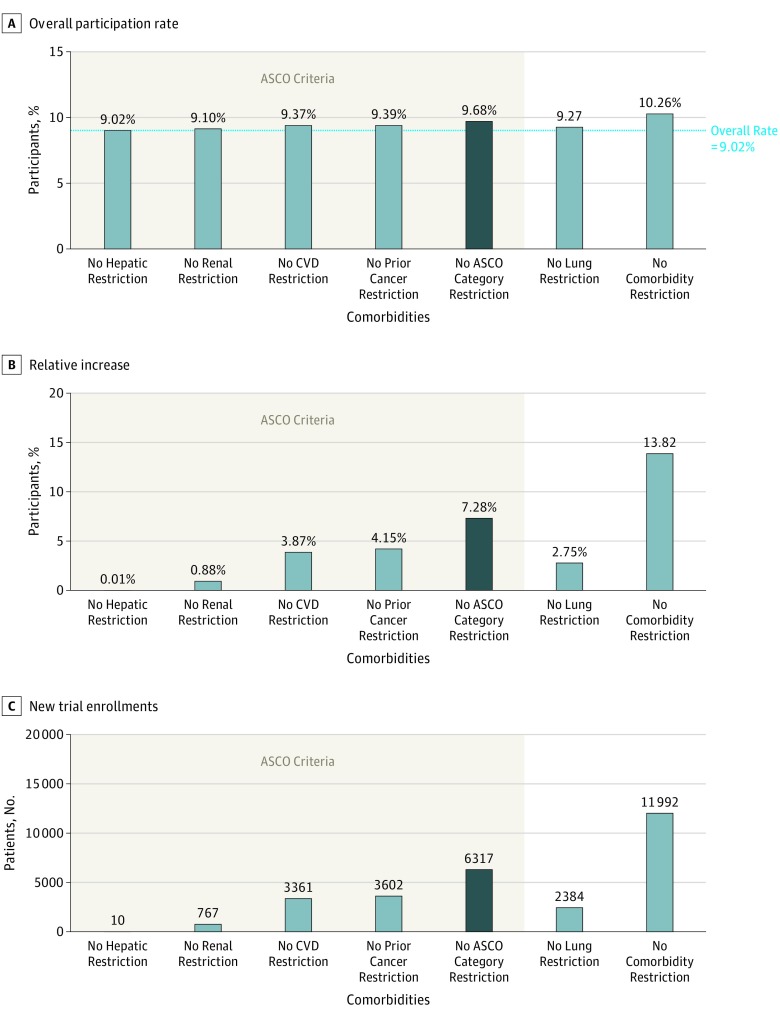

Figure 3 shows how the overall trial participation rate would change if the existence of major comorbidities did not exclude patients from participating in clinical trials. The individual comorbidity categories with the largest impact were prior cancer and cardiovascular disease. If patients with any of the comorbidities addressed in the ASCO recommendations enrolled at the same rate as those with no major comorbidities, the trial enrollment rate would increase from 9.02% to 9.68% (Figure 3A), a relative increase of 7.28% (Figure 3B). Assuming cancer incidence of 1 735 350 new cases in the United States in 2018 and a trial participation rate of 5.0% on average, the removal of all restrictions on the ASCO-recommended categories would allow up to 6317 additional patients (Figure 3C) to participate in cancer trials in 2018.20 If the underlying trial participation rate were 3%, 4%, 6%, 7%, or 8%, the removal of all restrictions on the ASCO-recommended categories would allow up to 3790, 5053, 7580, 8843, or 10 107, additional patients, respectively, to participate in cancer clinical trials in 2018. If patients with any of the major comorbidities participated in trials at the same rate as those with no conditions, up to 11 992 additional patients would participate; thus, targeting the ASCO criteria alone would account for more than half (6317 of 11 992; 52.7%) of the potential benefits of removing all the major comorbidity-related eligibility criteria.

Figure 3. Estimated Trial Participation Rates Based on Removing Restrictions to Comorbidity Eligibility Criteria.

A, Simulated rates of trial participation when selected comorbid conditions or categories of conditions were removed from protocol eligibility. B, The corresponding increases in trial participation rates relative to the overall trial participation rate of 9.02%. C, The resulting estimated number of new trial enrollments for US patients with cancer in 2018. Estimates based on comorbidity types aligned with the ASCO-recommended criteria are indicated by the bottom bracket. ASCO indicates American Society of Clinical Oncology; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Sensitivity Analyses

The inclusion of age as a 3-level covariate (18-39 vs 40-64 vs ≥65 years) in multivariable regressions did not substantively change the association of either 0 vs 1 or more comorbidities (from Figure 1) or 0 vs 1 vs 2 or more of the common predictors (hypertension, prior cancer, and hearing loss from Figure 2) with trial decision-making outcomes (eTable 5 in the Supplement). We examined whether the inclusion of patients with prior cancers may have influenced the results for other comorbidities. With the 10.2% of patients with prior cancer excluded, the association of 0 vs 1 or more comorbidities and trial decision-making outcomes was similar (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

We found that individual and combinations of comorbidities adversely affected discussions about trial participation, offers of trial participation, and trial participation itself, even after adjusting for important demographic and socioeconomic factors. Moreover, our simulation analyses suggested that the modernization of trial eligibility criteria could provide an opportunity for several thousand more patients with well-managed comorbidities to participate in cancer clinical trials each year.

Physicians consistently identify comorbidities as one of the reasons for excluding patients from clinical trials.21 The literature shows that the majority of trial exclusion criteria pertain to health status as reflected by vital organ function, prior cancer, HIV or other serious medical conditions, performance status, or receipt of prior cancer treatments.10 However, limited evidence exists about the relationship between comorbidity and trial participation rates. In an analysis of 495 NCI-sponsored trials from 1997 to 2000, Lewis et al22 found that organ-system abnormalities and functional status limitations were associated with low rates of trial participation among older adults in particular. A review of screening log data from 2009 to 2012 identified comorbidities and prior treatment as prominent reasons for trial ineligibility.23 In contrast to these prior examinations, the present study was able to characterize comorbidity status and its relationship to multiple trial participation outcomes (including trial discussions, trial offers, and trial participation) using patient-level data.

One rationale for the exclusion of prior cancers is that their presence may complicate the interpretation of outcomes for the current disease.21 However, recent evidence suggests that the existence of prior cancers has limited or no impact on outcomes for new diagnoses.24,25,26,27,28 For this reason, in part, the ASCO working group concluded that patients with prior cancers should be included, particularly when the impact on safety or efficacy is low.15 This should improve potential access to trials for millions of cancer survivors, for whom cancer is increasingly viewed as a chronic disease.29,30 Hearing loss was also a major determinant of trial decision making and participation. Hearing loss is common, and both hearing loss and cancer rates increase with age.5,31 Although hearing loss is rarely specified as an exclusion criteria, the presence of hearing loss is likely a critical hurdle to communication, implicitly hindering discussions about trials.32,33 Simple provisions such as easy-to-understand brochures, amplification with headsets, or other approaches to improve communication may help limit this barrier.34 About 70% of US individuals 65 years or older have hypertension, and in about half these cases, the hypertension is controlled, representing a large pool of potential candidates for trials.35 However, evidence as to whether hypertension adversely affects outcomes is mixed, although its effect on cardiac toxic effects is clear.36,37

Estimates of trial participation for adults with cancer in the United States are typically 5% or lower.1,2,3 A 7.3% relative increase in overall accrual—estimated to occur if none of the ASCO categories of major comorbidity exclusion criteria were included in trials—would generate up to 6317 additional cancer clinical trial registrations in 2018.20 This estimate represents an upper bound that is unlikely to fully materialize in practice, since most trial eligibility changes regarding comorbidities will likely modify selected ASCO criteria, rather than remove criteria altogether. Indeed, the goal is always to manage patient comorbidities safely and appropriately, which may only be consistent with modifying some criteria rather than removing them. Nonetheless it is likely that comorbidity eligibility changes will ultimately represent opportunities for trial participation for several thousand patients with cancer each year. Moreover, the fact that modifications to the ASCO-recommended comorbidity categories alone would represent more than half (52.7%) of the potential improvements in trial participation rates compared with removing all major comorbidity-related eligibility criteria suggests that the new ASCO guideline criteria are both targeted and clinically meaningful for patients with cancer.

Limitations

As previously shown,16 survey participants were representative with respect to geographic distribution, sex, and socioeconomic status, but were less likely to be older—perhaps reflecting the web-based nature of the survey—or African American, limiting the potential generalizability of the study results. Our approach required self-reported data, which may be a limitation with respect to the reporting of disease conditions. However, common disease conditions were represented in the study cohort at approximately expected rates. Although this could still mask misclassification, multiple studies have shown the self-reports of many common disease conditions have strong sensitivity and specificity.38,39,40,41 These results suggest that study participants provided reasonably reliable profiles of their health status on average, improving confidence in the results of our analysis about comorbidity predictors of trial participation, despite the limitations of self-report. Moreover, we had limited power to examine outcome differences for comorbidities that were rarely reported (eg, Alzheimer disease). Furthermore, the data could not be cross-validated with clinical records, and lacked information on severity of comorbidities.

Conclusions

Independent of important demographic and socioeconomic factors, the presence of comorbidities adversely affects trial discussions, trial offers, and trial participation itself. Additional research is required to further establish which comorbidities most strongly and negatively affect trial participation. This is particularly important in the era of biomarker-driven trials, which threaten to shrink eligible patient pools still further based on biomarker status. The modernization of trial eligibility criteria will benefit patients interested in participating by expanding their opportunities to receive care in trials. The participation of more patients will speed the rate at which trials can be conducted, and thus the rate at which new treatments and regimens are identified, benefiting all patients. But for most patients, simply accessing an available trial is a major hurdle, further complicated by issues of eligibility restrictions and physician and patient barriers. Thus, in addition to the important efforts made to address clinical and attitudinal barriers to trial participation, larger structural changes will also be required to substantially increase treatment trial participation for adults with cancer.

eTable 1. List of comorbid conditions

eQuestions. Clinical trial treatment decision-making questions

eTable 2. Sociodemographic and cancer characteristics of the cohort

eTable 3. Prevalence of common disease conditions in study cohort versus U.S. population of similar age distribution

eTable 4. Multivariable associations of individual comorbid conditions and trial discussion, offer, and participation

eFigure: Forest plot of the association between comorbidity risk scores and outcomes

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720-2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tejeda HA, Green SB, Trimble EL, et al. Representation of African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites in National Cancer Institute cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(12):812-816. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.12.812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger JM, Cook E, Tai E, Bleyer A. The role of clinical trial participation in cancer research: barriers, evidence, and strategies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:185-198. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_156686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA Jr, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2061-2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unger JM, Coltman CA Jr, Crowley JJ, et al. Impact of the year 2000 Medicare policy change on older patient enrollment to cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(1):141-144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C, et al. FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 10-year experience by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15):10009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.10009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javid SH, Unger JM, Gralow JR, et al. A prospective analysis of the influence of older age on physician and patient decision-making when considering enrollment in breast cancer clinical trials (SWOG S0316). Oncologist. 2012;17(9):1180-1190. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemeny MM, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, et al. Barriers to clinical trial participation by older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2268-2275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unger JM, Barlow WE, Martin DP, et al. Comparison of survival outcomes among cancer patients treated in and out of clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(3):dju002. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green S, Benedetti J, Smith A, Crowley J. Clinical Trials in Oncology. 3rd ed Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spitznagel EL Jr. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2441-2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Society of Clinical Oncology ASCO in Action: Initiative to modernize eligibility criteria for clinical trials launched. May 17, 2016. https://www.asco.org/advocacy-policy/asco-in-action/initiative-modernize-eligibility-criteria-clinical-trials-launched. Accessed March 11, 2018.

- 14.Jin S, Pazdur R, Sridhara R. Re-evaluating eligibility criteria for oncology clinical trials: analysis of investigational new drug applications in 2015. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3745-3752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, et al. Broadening eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research joint research statement. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3737-3744. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unger JM, Hershman DL, Albain KS, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):536-542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.4553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furnival GM, Wilson RW. Regressions by leaps and bounds. Technometrics. 1974;16(4):499-511. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1974.10489231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtman SM, Harvey RD, Damiette Smit MA, et al. Modernizing clinical trial eligibility criteria: recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology–Friends of Cancer Research Organ Dysfunction, Prior or Concurrent Malignancy, and Comorbidities Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3753-3759. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute Cancer Statistics. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics. Accessed May 23, 2018.

- 21.Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):3112-3124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1383-1389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.St Germain D, Denicoff AM, Dimond EP, et al. Use of the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program screening and accrual log to address cancer clinical trial accrual. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(2):e73-e80. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsdottir G, Lund SH, Björkholm M, et al. The impact of prior malignancies on second malignancies and survival in MM patients: a population-based study. Blood Adv. 2017;1(25):2392-2398. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017007930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laccetti AL, Pruitt SL, Xuan L, Halm EA, Gerber DE. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(4):djv002. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Møller P, Seppälä T, Bernstein I, et al. ; Mallorca Group (http://mallorca-group.org) . Incidence of and survival after subsequent cancers in carriers of pathogenic MMR variants with previous cancer: a report from the prospective Lynch syndrome database. Gut. 2017;66(9):1657-1664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pruitt SL, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, Halm EA, Gerber DE. Revisiting a longstanding clinical trial exclusion criterion: impact of prior cancer in early-stage lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(6):717-725. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smyth EC, Tarazona N, Peckitt C, et al. Exclusion of gastrointestinal cancer patients with prior cancer from clinical trials: is this justified? Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15(2):e53-e59. Published online November 27, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “silver tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(7):1029-1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips JL, Currow DC. Cancer as a chronic disease. Collegian. 2010;17(2):47-50. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin FR, Niparko JK, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1851-1852. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iezzoni LI, O’Day BL, Killeen M, Harker H. Communicating about health care: observations from persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):356-362. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meador HE, Zazove P. Health care interactions with deaf culture. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(3):218-222. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.3.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adelman RD, Greene MG, Ory MG. Communication between older patients and their physicians. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16(1):1-24, vii. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0690(05)70004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension—United States, 1999-2002 and 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):103-108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braithwaite D, Tammemagi CM, Moore DH, et al. Hypertension is an independent predictor of survival disparity between African-American and white breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(5):1213-1219. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hershman DL, Till C, Shen S, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with cardiac events and survival outcomes among patients with breast cancer enrolled in SWOG clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(26):2710-2717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.4414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bush TL, Miller SR, Golden AL, Hale WE. Self-report and medical record report agreement of selected medical conditions in the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(11):1554-1556. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.79.11.1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1096-1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vigen C, Kwan ML, John EM, et al. Validation of self-reported comorbidity status of breast cancer patients with medical records: the California Breast Cancer Survivorship Consortium (CBCSC). Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(3):391-401. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0715-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merkin SS, Cavanaugh K, Longenecker JC, Fink NE, Levey AS, Powe NR. Agreement of self-reported comorbid conditions with medical and physician reports varied by disease among end-stage renal disease patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(6):634-642. Published online December 11, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. List of comorbid conditions

eQuestions. Clinical trial treatment decision-making questions

eTable 2. Sociodemographic and cancer characteristics of the cohort

eTable 3. Prevalence of common disease conditions in study cohort versus U.S. population of similar age distribution

eTable 4. Multivariable associations of individual comorbid conditions and trial discussion, offer, and participation

eFigure: Forest plot of the association between comorbidity risk scores and outcomes

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses