Key Points

Question

Is neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by local excision a feasible alternative to conventional total mesorectal excision?

Finding

In this phase II feasibility study of 55 patients, organ preservation was achieved in 35 patients (64%) with acceptable long-term oncological outcomes and health-related quality of life. However, most patients experienced a certain degree of functional impairment.

Meaning

Organ preservation may be a feasible alternative to total mesorectal excision for patients with a desire for organ preservation.

This phase II feasibility study explores the long-term oncological outcomes and health-related quality of life of patients with cT1-3N0M0 rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by transanal endoscopic microsurgery.

Abstract

Importance

Treatment of rectal cancer is shifting toward organ preservation aiming to reduce surgery-related morbidity. Short-term outcomes of organ-preserving strategies are promising, but long-term outcomes are scarce in the literature.

Objective

To explore long-term oncological outcomes and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with cT1-3N0M0 rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) followed by transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM).

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this multicenter phase II feasibility study, patients with cT1-3N0M0 rectal cancer admitted to referral centers for rectal cancer throughout the Netherlands between February 2011 and September 2012 were prospectively included. These patients were to be treated with neoadjuvant CRT followed by TEM in case of good response. An intensive follow-up scheme was used to detect local recurrences and/or distant metastases. Data from validated HRQL questionnaires and low anterior resection syndrome questionnaires were collected. Data were analyzed from February 2011 to April 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary study outcome of the study was the number of ypT0-1 specimens by performing TEM. Secondary outcome parameters were locoregional recurrences and HRQL.

Results

Of the 55 included patients, 30 (55%) were male, and the mean (SD) age was 64 (39-82) years. Patients were followed up for a median (interquartile range) period of 53 (39-57) months. Two patients (4%) died during CRT, 1 (2%) stopped CRT, and 1 (2%) was lost to follow-up. Following CRT, 47 patients (85%) underwent TEM, of whom 35 (74%) were successfully treated with local excision alone. Total mesorectal excision was performed in 16 patients (4 with inadequate responses, 8 with completion after TEM, and 4 with salvage for local recurrence). The actuarial 5-year local recurrence rate was 7.7%, with 5-year disease-free and overall survival rates of 81.6% and 82.8%, respectively. Health-related quality of life during follow-up was equal to baseline, with improved emotional well-being in patients treated with local excision (mean score at baseline, 72.0; 95% CI, 67.1-80.1; mean score at follow-up, 86.9; 95% CI, 79.2-94.7; P = .001). Major, minor, and no low anterior resection syndrome was experienced in 50%, 28%, and 22%, respectively, of patients with successful organ preservation.

Conclusions and Relevance

In early-stage rectal cancer (cT1-3N0M0), CRT enables organ preservation with additional TEM surgery in approximately two-thirds of patients with good long-term oncological outcome and HRQL. This multimodality treatment triggers a certain degree of bowel dysfunction, and one-third of patients still undergo radical surgery and are overtreated by CRT.

Introduction

Curative local treatment of rectal cancer consists of surgery following the principle of total mesorectal excision (TME).1 However, TME is associated with high morbidity rates and impaired functional outcomes. After a sphincter-preserving low anterior resection, approximately 60% of patients suffer from specific bowel disorders, known as low anterior resection syndrome (LARS).2,3 Complaints of LARS consist of clustering stools, soiling, and fecal incontinence. Patients who cannot undergo sphincter-preserving surgery require a definite colostomy, which might affect body image and health-related quality of life (HRQL).4,5,6

Local excision is considered a valid treatment option for very early tumors (pT1) without lymphatic spread.7 More advanced tumors have a higher risk of recurrence after a local excision compared with TME because of occult lymph node metastasis and intraluminal recurrences.8,9 This implies that most intermediate-risk rectal cancers need some form of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment if local excision is preferred.10 Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) has shown to reduce the risk of local recurrences by increasing the chance of a radical resection in locally advanced rectal cancers.11 This treatment can achieve a partial response in approximately 54% to 75% of patients and a pathological complete response in 8% to 27% of patients.12,13,14

The absence of viable tumor after neoadjuvant CRT led to a growing interest in alternative strategies for treating rectal cancer. Organ-preserving treatment options aim for improving HRQL with similar oncological outcome. Several retrospective studies describe the effect of transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) in patients who respond well to neoadjuvant treatment for clinical T1-3N0 rectal cancer.15,16,17,18,19 Preservation of the rectum could be achieved in 73% to 95% of patients with acceptable local control. Unfortunately, these studies were limited from rather short follow-up periods. Long-term oncological outcome data as well as HRQL data are scarce, with only 3 other series, to our knowledge, presenting long-term outcome data.20,21,22

The Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group conducted a prospective, multicenter study (Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery After Radiochemotherapy for Rectal Cancer [CARTS] study) exploring the feasibility of local excision after neoadjuvant CRT in patients with distal cT1-3N0 rectal cancer. The feasibility and short-term oncological outcomes have already been reported.23 The study was also designed to analyze long-term HRQL together with functional outcomes of these patients. In this report, long-term oncological outcomes together with HRQL are described.

Methods

Study Design

The study design of the CARTS study has previously been published,24 and the trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1. It was a phase II feasibility study in which patients with cT1-3N0M0 rectal cancer were enrolled. The tumor had to be located within 10 cm of the anal verge and require treatment with abdominoperineal resection or low anterior resection with coloanal anastomosis. The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Radboud University Medical Centre and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov in 2011 (NCT01273051). All patients provided written informed consent. All patients underwent digital rectal examination, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT), chest radiography or CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis. The fifth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria was used for tumor staging.

Procedures

Neoadjuvant treatment consisted of a total dose of 50 Gy or 50.4 Gy, given in 25 fractions of 2 Gy or in 28 fractions of 1.8 Gy, respectively, combined with capecitabine, 825 mg/m2, twice daily on all days. The clinical target volume of the radiotherapy consisted of the tumor with mesorectal fat, internal iliac, obturator, and presacral nodes. The upper field border was at the level of the promontory.25 Patients with significant downsizing of the tumor (ycT0-2) 8 to 10 weeks after the last CRT treatment were eligible for local excision. Local excision was performed using TEM surgery, which consisted of full-thickness excision of the tumor with a margin of 2 mm or more. When histological examination revealed insufficient pathological downstaging (ypT2-3), patients were advised to undergo completion TME within 4 to 6 weeks after TEM. Patients who showed a poor response on clinical evaluation (ycT3-4) were scheduled to undergo TME 8 to 10 weeks after CRT.

Follow-up

An intensive follow-up schedule over 36 months was designed for patients who underwent TEM, which was intended for early detection of possible local recurrence and/or distant metastases. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels were measured every 3 months together with rectal examination, which included digital rectal examination, rectoscopy, and endorectal ultrasonography. Every 6 months, an MRI of the pelvis and a CT scan of the thorax and abdomen were required. After 2 years, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, digital rectal examination, rectoscopy, and endorectal ultrasonography were performed every 6 months and the pelvis MRI and CT scan of thorax and abdomen every 12 months.

Outcomes

The primary end point of the study was the number of patients with minimal residual (ypT0-1) disease, which has been published previously.23 Secondary end points of the study were the number of local recurrences of patients treated with TEM or TME surgery as events in the time-to-event Kaplan-Meier analysis as well as fecal continence and HRQL in all patients.26 Health-related quality of life was assessed according to European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life (EORTC QLQ) core 30 (C30) and colorectal 38 (CR38) questionnaires.27 Prior to the start of treatment, HRQL questionnaires were filled in by patients and collected at rectal cancer referral centers throughout the Netherlands. Subsequently, EORTC QLQ C30 and CR38 questionnaires were sent to patients 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after surgical treatment. Additionally, LARS questionnaires were sent to patients treated with successful organ preservation after a minimum follow-up period of 48 months to objectify bowel function.3 The LARS questionnaire is a validated scoring system to evaluate bowel function after a low anterior resection. Five questions regarding incontinence for flatus and liquid stools as well as frequency, clustering, and urgency for defecation are taken into account. The score ranges from 0 to 42 and is divided into no LARS (0 to 20 points), minor LARS (21 to 29 points), and major LARS (30 to 42 points).

Data management was done by registered clerks of the Netherlands Cancer Registry. Information from participating hospitals was collected on case report forms that were sent to the central office.

Statistical Analysis

Five-year local recurrence, distant metastasis, disease-free survival, and overall survival rates from the start of CRT were calculated with Kaplan-Meier curves. Outcomes of the HRQL questionnaires were described using means and standard deviations. Nominal and ordinal values are presented in 2-way contingency tables. Differences in the outcomes of the EORTC QLQ C30 and CR38 questionnaires within patients were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The level of statistical significance was set at a P value less than .01 to correct for multiple testing, and all P values were 2-tailed. Outcomes of the LARS questionnaires were displayed in a histogram. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM).

Results

A total of 55 patients were included in this study from 9 Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group centers, of whom 30 (55%) were male and 25 (45%) were female. After MRI revision, 50 patients (91%) were diagnosed as having a clinically resectable cT1-3N0 adenocarcinoma of the rectum and 5 (9%) as having cT1-3N1. All tumors were located in the distal part of the rectum (Table 1), and no patients had extramural venous invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or poor differentiation. During neoadjuvant CRT, 2 patients died of sepsis and possible arrhythmia. Two other patients were unable to continue CRT because of a toxic reaction, of whom 1 was lost to follow-up. A total of 47 patients (85%) subsequently underwent TEM surgery, and 4 patients (7%) underwent primary TME as a result of insufficient response to CRT. All but 1 of the resection margins of the TEM specimens were tumor free. The patient with an incomplete margin as well as 7 other patients with ypT2-3N0-1 tumors after local excision underwent completion TME surgery (eFigure in Supplement 2).23 The circumferential resection margins of all TME specimens were tumor free.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Included Patients.

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 55) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (interquartile range), y | 64 (39-82) |

| Male, No. (%) | 30 (55) |

| Tumor size, median (interquartile range), cm | 3.4 (3.0-5.0) |

| Clinical tumor category, No. (%) | |

| cT1 | 10 (18) |

| cT2 | 29 (53) |

| cT3 | 16 (29) |

| Clinical node category, No. (%) | |

| cN0 | 50 (91) |

| cN1 | 5 (9) |

| Distance to anal verge, median (interquartile range), cm | 3.5 (2.0-6.0) |

Long-term Outcome

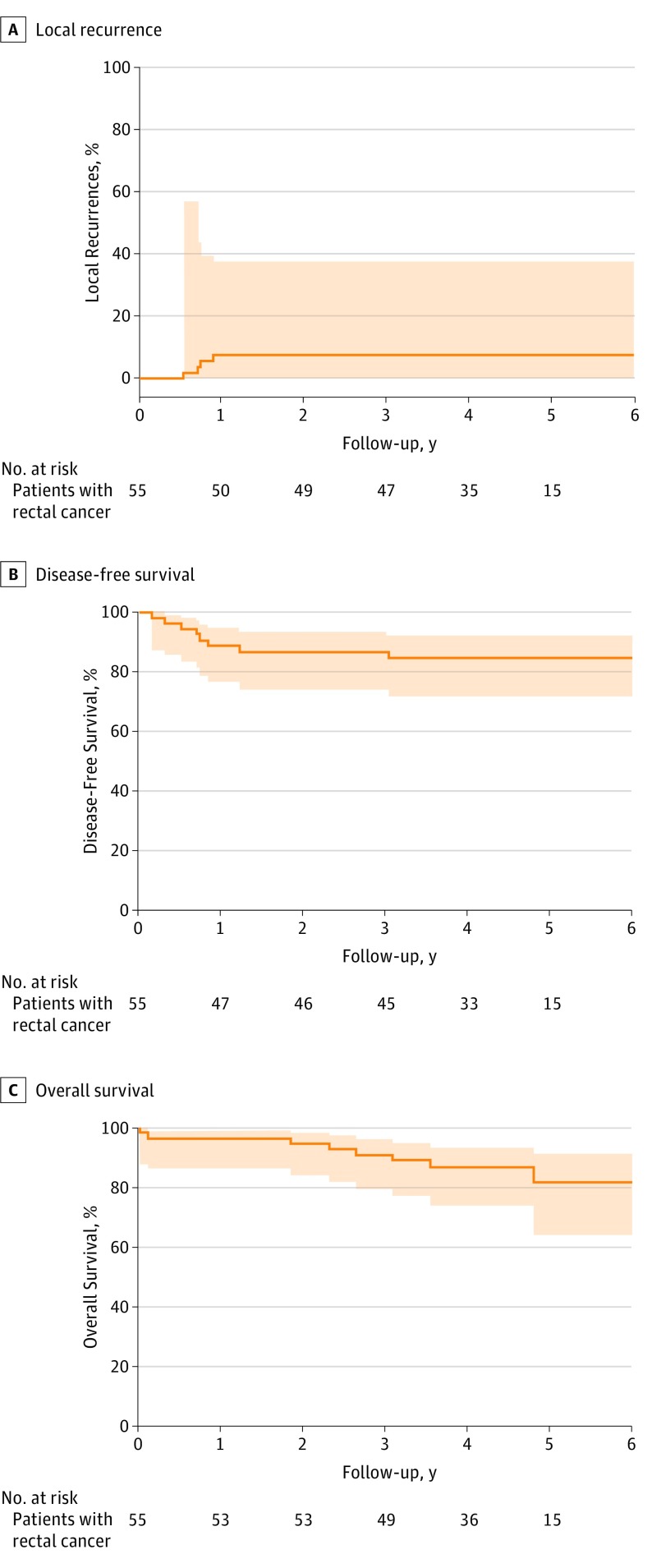

After a median (interquartile range) follow-up of 53 (39-57) months, 4 of 47 patients (9%) in the organ preservation group developed an intraluminal local recurrence. All occurred within 12 months after local excision and were treated with salvage TME. Local recurrences occurred in 1 patient with a ypT1 tumor and in another 3 patients with a ypT2 tumor who initially refused completion TME. None of the patients undergoing primary TME developed a locoregional recurrence. This resulted in an actuarial 5-year local recurrence rate of 7.7% (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Analyses of Local Recurrence and Disease-Free and Overall Survival for All Patients With Rectal Cancer From the Start of Chemoradiotherapy After a Median Follow-up of 53 Months.

The area above and below the curve indicates the 95% CI.

The actuarial 5-year disease-free survival was 81.6% (Figure 1B). Three of 4 patients who were diagnosed as having a local recurrence also developed distant metastases. Despite treatment of both the recurrence and the metastases, all 3 eventually died. Metachronous distant metastases occurred in 4 other patients, of whom 3 patients developed lung metastases and 1 patient developed liver metastases. These patients underwent local and/or systemic therapy; of these patients, 1 is alive without disease. The actuarial 5-year overall survival rate of all included patients was 82.8% (Figure 1C).

Quality of Life

The EORTC QLQ C30 and CR38 questionnaires were completed by 22, 32, 19, and 24 patients after follow-up periods of 6, 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively. It was assumed that symptoms and bowel function generally would stabilize 12 months after surgical intervention28; therefore, the outcomes with the largest interval from baseline with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months were selected for evaluation. Forty-three patients, of whom 33 (77%) underwent TEM and 10 (23%) underwent TME, completed the questionnaires. Of the 10 patients who underwent TME, 6 were treated with TME after TEM surgery.

Outcomes of the EORTC QLQ C30 revealed an improved emotional functioning score for patients undergoing TEM (Table 2). For patients undergoing TME, no significant differences were revealed (Table 2). The outcomes of the EORTC QLQ CR38 questionnaires for the patients undergoing TEM showed a significant reduction of blood and mucus in stools but also revealed increased anxiety. Subanalyses comparing the anxiety scores during follow-up after TEM between pathological complete and incomplete responders showed a significant difference (58.9 vs 79.5, respectively; P = .04). No significant differences were discovered between baseline and follow-up within the group of patients treated with TME after CRT (Table 3).

Table 2. Outcome of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life (EORTC QLQ) Core 30 Questionnaire at Baseline Compared After a Minimum Follow-up of 1 Year for 33 Patients Treated With Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) and 10 Patients Treated With Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) After Chemoradiotherapy.

| EORTC QLQ Category | EORTC QLQ Score, Mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEM | P Valuea | TME | P Valuea | |||

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |||

| Global Health score | 75.5 | 74.4 | .73 | 81.7 | 73.1 | .17 |

| Physical Functioning score | 89.7 | 83.3 | .06 | 92.0 | 83.0 | .03 |

| Role Functioning score | 86.7 | 84.4 | .59 | 91.7 | 85.2 | .18 |

| Emotional Functioning score | 72.0 | 86.9 | .001 | 76.7 | 80.6 | >.99 |

| Cognitive Functioning score | 88.4 | 88.9 | .72 | 93.3 | 90.7 | .71 |

| Social Functioning score | 88.4 | 89.4 | .60 | 98.3 | 88.9 | .10 |

| Fatigue score | 20.2 | 21.9 | .60 | 12.2 | 18.7 | .03 |

| Nausea and Vomiting score | 4.0 | 2.5 | .67 | 5.0 | 24.7 | .03 |

| Pain score | 8.1 | 12.7 | .06 | 6.7 | 3.7 | .16 |

| Dyspnoe score | 15.2 | 12.8 | .48 | 10.0 | 18.5 | .29 |

| Insomnia score | 22.2 | 14.4 | .16 | 16.7 | 11.1 | >.99 |

| Appetite Loss score | 5.1 | 17.8 | .02 | 3.3 | 25.9 | .04 |

| Constipation score | 8.1 | 5.6 | .56 | 6.7 | 7.4 | .66 |

| Diarrhea score | 13.1 | 7.8 | .36 | 10.0 | 14.8 | .66 |

| Financial Difficulties score | 7.1 | 13.3 | .17 | 10.0 | 7.4 | .79 |

Calculated using Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Table 3. Outcome of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life (EORTC QLQ) Colorectal 38 Questionnaire at Baseline Compared After a Minimum Follow-up of 1 Year for 33 Patients Treated With Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) and 10 Patients Treated With Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) After Chemoradiotherapy.

| EORTC QLQ Category | EORTC QLQ Score, Mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEM | P Valuea | TME | P Valuea | |||

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |||

| Body Image score | 95.5 | 88.1 | .08 | 97.2 | 79.0 | .11 |

| Anxiety score | 49.4 | 69.0 | .005 | 58.3 | 74.1 | .32 |

| Weight Loss score | 97.5 | 98.8 | .32 | 91.7 | 96.3 | .56 |

| Sexual Interest score | 56.9 | 59.0 | .44 | 48.9 | 66.7 | .16 |

| Urinary Frequency score | 24.1 | 29.2 | .26 | 35.4 | 33.3 | .50 |

| Blood and Mucus in Stool score | 29.5 | 2.7 | .001 | 41.7 | 0 | .32 |

| Stool Frequency score | 20.0 | 21.3 | .72 | 22.2 | 27.8 | .32 |

| Dysuria score | 1.3 | 8.3 | .13 | 8.3 | 11.1 | .56 |

| Abdominal Pain score | 11.1 | 13.1 | .45 | 16.7 | 14.8 | >.99 |

| Buttock Pain score | 13.6 | 22.6 | .12 | 8.3 | 25.9 | .20 |

| Bloating score | 11.1 | 15.5 | .19 | 20.8 | 11.1 | .08 |

| Dry Mouth score | 8.6 | 8.3 | .32 | 16.7 | 11.1 | .41 |

| Hair Loss score | 4.9 | 9.5 | .41 | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Taste score | 1.2 | 2.4 | .32 | 0 | 3.7 | .32 |

| Flatulence score | 34.6 | 38.3 | .33 | 37.5 | 11.1 | .23 |

| Fecal Incontinence score | 10.3 | 18.7 | .25 | 16.7 | 33.3 | .32 |

| Painful Stools score | 8.3 | 4.7 | .16 | 20.8 | 50.0 | .32 |

| Sore Skin score | NA | 16.7 | NA | NA | 16.7 | NA |

| Embarrassment score | NA | 16.7 | NA | NA | 35.2 | NA |

| Stoma Care Problems score | NA | NA | NA | NA | 66.7 | NA |

| Impotence score | 18.2 | 37.9 | .78 | 20.8 | 63.3 | .18 |

| Dyspareunia score | 4.2b | 21.4c | .18 | 0 | NA | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Calculated using Wilcoxon signed rank test.

n = 4.

n = 7.

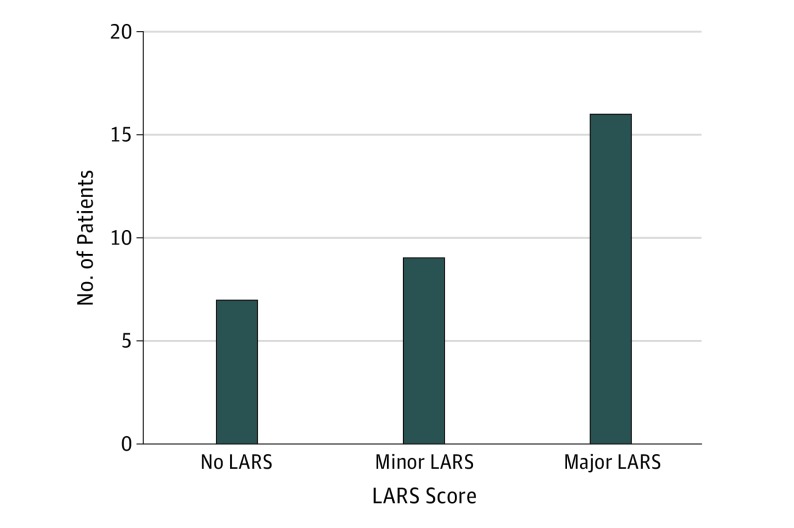

Low anterior resection syndrome scores were retrieved from 32 of 35 patients (91%) who underwent successful organ-preserving treatment. These scores were retrieved 48 to 68 months after surgical treatment. Of these 32 patients, 7 (22%) did not have LARS, 9 (28%) had minor LARS, and 16 (50%) had major LARS (Figure 2). Six patients who underwent subsequent TME surgery had bowel continuity. Low anterior resection syndrome scores were only available in 1 patient and therefore could not be analyzed as a subgroup.

Figure 2. Histogram of Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS) Scores Categorized for Patients Undergoing Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery.

Discussion

Neoadjuvant CRT followed by TEM for resectable early rectal cancer seems to be a feasible approach for patients who desire organ preservation. In this prospective multicenter study, the rectum could be preserved in 64% of patients with cT1-3N0 rectal cancer. Local recurrences were observed in 1 patient with stage ypT1 cancer after TEM and in 3 patients who initially refused completion TME for ypT2 stage cancer over a median follow-up period of 53 months. The actuarial 5-year disease-free and overall survival rates were 81.6% and 82.8%, respectively. Despite these favorable oncological outcomes, functional results revealed that 50% of patients in whom the rectum was preserved experienced major symptoms similar to LARS. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that 2 patients died due to CRT-related complications and that one-third of the initially included patients with low-risk rectal cancer required TME surgery and underwent radiotherapy that would not have been given outside a trial setting.

Despite the optimization of rectal cancer treatment, the demand for less extensive surgery renewed the discussion on how to treat patients with early rectal tumors.29 Studies investigating organ preservation after neoadjuvant treatment for cT1-3 rectal cancer showed pathological complete response rates varying from 4% to 49% depending on various factors, such as size and location of the tumor.15,17,20 Complete response rates from these studies were based on local excision specimens, which can only be conclusive on T stage. Lymphovascular invasion, lymphatic spread, and tumor budding are strongly associated with malignant nodal involvement and local recurrences after neoadjuvant treatment for early rectal cancer and still can be demonstrated in up to 20% of patients.30,31,32

Nevertheless, promising local control and long-term survival rates have been described for this relatively new treatment regimen.15,16,17,20,32,33 Martens et al34 described a series of patients who were offered organ preservation after neoadjuvant CRT by a watch-and-wait procedure (24 patients) or TEM in case of residual tumor (15 patients). They reported a local recurrence-free and disease-free survival of 84.6% and 80.6%, respectively, after a median follow-up period of 41 months. Creavin et al35 published prospective results of 60 of 362 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who were treated with an organ-preserving intention after CRT. Fifty patients underwent local excision, of whom 15 patients (30%) had to undergo salvage TME and 10 patients (20%) underwent a watch-and-wait procedure. There were no significant differences in disease-free and overall survival for the organ-preservation groups compared with the 302 patients treated with TME surgery after CRT. Pucciarelli et al17 showed that successful organ preservation by TEM surgery after CRT could be achieved in 43 of 63 well-responding patients with cT2-3 rectal cancer. Local recurrence–free survival and disease-free survival in all patients was 96.9% and 91.0%, respectively. The feasibility of TEM after CRT was also supported by the ACOSOG Z6041 trial,20 which showed successful organ preservation in cT2N0 tumors with a disease-free survival of 88.2% and proposed this regime as an alternative for well-responding patients.

Until now, to our knowledge, the only published randomized clinical trial comparing conventional TME with local excision after CRT is the GRECCAR 2 trial.22 In this trial, well-responding patients with cT2-3 distal rectal cancer were randomly assigned to one of the surgical interventions, but it did not demonstrate superiority of local excision over TME regarding morbidity, long-term effects, and oncological outcomes. This may be explained because a substantial proportion of patients analyzed in the local excision group eventually underwent a completion TME. Major morbidity or adverse effects were experienced in 78% of these patients compared with 29% of patients who underwent local excision alone and 38% of patients who underwent only TME surgery after CRT.

In the current study, the EORTC QLQ C30 and EORTC QLQ CR38 questionnaires were used to evaluate HRQL, treatment-specific symptoms, and adverse effects.27,36 These questionnaires revealed an improved emotional functioning but a worsened anxiety score after organ preservation. Increased anxiety was more prominent in patients with an incomplete pathological response after TEM surgery. Bowel dysfunction was common, with 50% of patients experiencing major LARS after CRT followed by TEM. On the other hand, outcomes of the EORTC QLQ C30 questionnaire could not demonstrate a difference in constipation scores and even demonstrated a reduction in diarrhea scores for patients with successful organ preservation. Therefore, LARS outcomes might have to be interpreted with caution, since LARS questionnaires are not validated for the treatment regimen of the current study.

Equivalent LARS scores are reported in the literature for upper or middle rectal tumors after a curative anterior resection.28,37,38,39 Only few studies report on HRQL and bowel function after organ preservation. Pucciarelli et al21 described better overall HRQL, constipation scores, and bowel function after local excision vs TME following CRT using similar questionnaires. Martens et al34 used the Vaizey incontinence and demonstrated that patients undergoing watch-and-wait procedures generally had good functional outcomes compared with 7 patients undergoing TEM with moderate outcomes. Major incontinence was seen in 42.8% of patients undergoing TEM, which seems in concordance with the results of the present study.

Defecation problems may be less prominent if local excision can be omitted after neoadjuvant CRT, since radiotherapy as well as local excision itself are risk factors for bowel dysfunction.38,40 In a matched-control study by Hupkens et al,41 bowel function and HRQL of 41 patients undergoing watch-and-wait procedures were compared with 41 patients undergoing TME after CRT. Although defecation problems and an impaired HRQL were present in both study cohorts, the watch-and-wait group reported substantially better functional outcomes and HRQL in several domains.

This prospective trial clearly confirms that neoadjuvant CRT followed by TEM is feasible for primarily resectable cancer. It should be further unraveled whether organ preservation is an acceptable alternative to standard surgery without neoadjuvant CRT, which is still standard treatment. Since 40% of patients were diagnosed with a complete pathological response and local recurrence rate was low, local excision was not necessary in a substantial number of patients. New organ-preserving studies should therefore include a watch-and-wait strategy in patients with a clinical complete response, potentially resulting in a further improved HRQL and bowel function. Several randomized trials are now ongoing exploring different neoadjuvant treatment regimens (NCT02945566; NCT02514278; NCT02505750; NCT01060007; and NCT02860234).

Limitations

This study had limitations. One limitation of the present study is the fact that the HRQL questionnaires were not consistently filled in by patients after the baseline assessment. As a consequence, baseline HRQL had to be compared with only a single moment during follow-up more than 1 year after treatment. Moreover, patients did not receive the LARS form at baseline.

Conclusion

In conclusion, neoadjuvant CRT followed by a full-thickness local excision can lead to preservation of the rectum in two-thirds of patients with low-risk distal rectal cancer. Long-term oncological outcome is good and HRQL does not seem to be impaired, but incontinence and defecation problems are not unambiguous. Randomized trials comparing organ-preserving strategies with standard TME surgery should give further answers in how to treat patients with resectable rectal cancer to optimize long-term results and HRQL.

Trial protocol.

eFigure. CONSORT diagram.

References

- 1.Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery—the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg. 1982;69(10):613-616. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800691019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, et al. . Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life: an international multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(5):585-591. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255(5):922-928. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824f1c21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thaysen HV, Jess P, Laurberg S. Health-related quality of life after surgery for primary advanced rectal cancer and recurrent rectal cancer: a review. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):797-803. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02668.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thaysen HV, Jess P, Rasmussen PC, Nielsen MB, Laurberg S. Health-related quality of life after surgery for advanced and recurrent rectal cancer: a nationwide prospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(7):O223-O233. doi: 10.1111/codi.12551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feddern ML, Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Life with a stoma after curative resection for rectal cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(11):1011-1017. doi: 10.1111/codi.13041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu JY, Lin GL, Qiu HZ, Xiao Y, Wu B, Zhou JL. Comparison of transanal endoscopic microsurgery and total mesorectal excision in the treatment of T1 rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.You YN, Baxter NN, Stewart A, Nelson H. Is the increasing rate of local excision for stage I rectal cancer in the United States justified? a nationwide cohort study from the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg. 2007;245(5):726-733. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252590.95116.4f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landmann RG, Wong WD, Hoepfl J, et al. . Limitations of early rectal cancer nodal staging may explain failure after local excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(10):1520-1525. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9019-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peeters KC, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group . The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246(5):693-701. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000257358.56863.ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. ; German Rectal Cancer Study Group . Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(17):1731-1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, et al. . Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(16):1926-1933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CAM, Nagtegaal ID, et al. ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group . Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):638-646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. . Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(9):835-844. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70172-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lezoche G, Baldarelli M, Guerrieri M, et al. . A prospective randomized study with a 5-year minimum follow-up evaluation of transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision after neoadjuvant therapy [published correction appears in Surg Endosc. 2008;22(1):278]. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(2):352-358. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9596-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smart CJ, Korsgen S, Hill J, et al. . Multicentre study of short-course radiotherapy and transanal endoscopic microsurgery for early rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103(8):1069-1075. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pucciarelli S, De Paoli A, Guerrieri M, et al. . Local excision after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: results of a multicenter phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(12):1349-1356. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a2303e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JJ, Chow OS, Gollub MJ, et al. ; Rectal Cancer Consortium . Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma: a phase II randomized controlled trial evaluating 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with chemoradiation plus induction or consolidation chemotherapy, and total mesorectal excision or nonoperative management. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:767. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1632-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, São Julião GP, et al. . Transanal local excision for distal rectal cancer and incomplete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation—does baseline staging matter? Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(11):1253-1259. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Aguilar J, Renfro LA, Chow OS, et al. . Organ preservation for clinical T2N0 distal rectal cancer using neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and local excision (ACOSOG Z6041): results of an open-label, single-arm, multi-institutional, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(15):1537-1546. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00215-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pucciarelli S, Giandomenico F, De Paoli A, et al. . Bowel function and quality of life after local excision or total mesorectal excision following chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2017;104(1):138-147. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rullier E, Rouanet P, Tuech JJ, et al. . Organ preservation for rectal cancer (GRECCAR 2): a prospective, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):469-479. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verseveld M, de Graaf EJ, Verhoef C, et al. ; CARTS Study Group . Chemoradiation therapy for rectal cancer in the distal rectum followed by organ-sparing transanal endoscopic microsurgery (CARTS study). Br J Surg. 2015;102(7):853-860. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bökkerink GM, de Graaf EJ, Punt CJ, et al. . The CARTS study: chemoradiation therapy for rectal cancer in the distal rectum followed by organ-sparing transanal endoscopic microsurgery. BMC Surg. 2011;11:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-11-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nuyttens JJ, Robertson JM, Yan D, Martinez A. The influence of small bowel motion on both a conventional three-field and intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for rectal cancer. Cancer Radiother. 2004;8(5):297-304. doi: 10.1016/S1278-3218(04)00086-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleming TR, Lin DY. Survival analysis in clinical trials: past developments and future directions. Biometrics. 2000;56(4):971-983. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.0971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. . The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S; Rectal Cancer Function Study Group . Impact of bowel dysfunction on quality of life after sphincter-preserving resection for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(10):1377-1387. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stijns RCH, Tromp MR, Hugen N, de Wilt JHW. Advances in organ preserving strategies in rectal cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(2):209-219. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosch SL, Teerenstra S, de Wilt JH, Cunningham C, Nagtegaal ID. Predicting lymph node metastasis in pT1 colorectal cancer: a systematic review of risk factors providing rationale for therapy decisions. Endoscopy. 2013;45(10):827-834. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, et al. ; Polish Colorectal Study Group . Prediction of mesorectal nodal metastases after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: results of a randomised trial: implication for subsequent local excision. Radiother Oncol. 2005;76(3):234-240. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, Lynn PB, et al. . Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for residual rectal cancer (ypT0-2) following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy: another word of caution. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(1):6-13. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318273f56f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Appelt AL, Pløen J, Harling H, et al. . High-dose chemoradiotherapy and watchful waiting for distal rectal cancer: a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):919-927. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00120-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martens MH, Maas M, Heijnen LA, et al. . Long-term outcome of an organ preservation program after neo-adjuvant treatment for rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(12). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Creavin B, Ryan E, Martin ST, et al. . Organ preservation with local excision or active surveillance following chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(2):169-174. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Aaronson NK; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study Group on Quality of Life . The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(2):238-247. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheer AS, Boushey RP, Liang S, Doucette S, O’Connor AM, Moher D. The long-term gastrointestinal functional outcomes following curative anterior resection in adults with rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(12):1589-1597. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182214f11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Battersby NJ, Juul T, Christensen P, et al. ; United Kingdom Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Study Group . Predicting the risk of bowel-related quality-of-life impairment after restorative resection for rectal cancer: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(4):270-280. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pucciarelli S, Del Bianco P, Efficace F, et al. . Patient-reported outcomes after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: a multicenter prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2011;253(1):71-77. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fcb856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doornebosch PG, Tollenaar RA, Gosselink MP, et al. . Quality of life after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and total mesorectal excision in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(6):553-558. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. . Quality of life in rectal cancer patients after chemoradiation: watch-and-wait policy versus standard resection—a matched-controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(10):1032-1040. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol.

eFigure. CONSORT diagram.