Abstract

This study examines the association between rotavirus vaccination and declining rates of type 1 diabetes in children.

Introduction

Rotavirus (RV) infection has been associated with the development of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in children.1 Rotavirus infection triggers pancreatic apoptosis in mice, and RV peptides display molecular mimicry with T-cell epitopes in pancreatic β-cell autoantigens.2 We hypothesized that if natural infection with RV was a causative factor in T1D, then RV vaccination would decrease the incidence of disease over time. Therefore, using publicly available data, we examined the incidence of T1D in Australian children before and after the oral RV vaccine was introduced to the Australian National Immunisation Program in 2007.

Methods

An interrupted time-series analysis was performed on the incidence of newly diagnosed T1D in Australian children in the 8 years before compared with the 8 years after the May 2007 introduction of routine oral RV vaccination for all infants aged 6 weeks and older. National coverage for RV vaccine at this time was estimated to be 84%. Nearly all Australian children newly diagnosed with T1D are registered with the National Diabetes Services Scheme for subsidized provision of glucose testing and insulin delivery consumables (https://www.ndss.com.au/). National Diabetes Services Scheme data are provided to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (https://www.aihw.gov.au/). Using the publicly available data from this source, we determined the observed and modeled rates of new-onset T1D between 2000 and 2015. Population numbers for children aged 0 to 4 years, 5 to 9 years, and 10 to 14 years in Australia over this period were sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics website (http://www.abs.gov.au/). Interrupted time-series modeling of preintervention and postintervention patterns and changes in the numbers of newly incident cases using the published numbers of cases in children aged 0 to 14 years were performed.

This study was approved by the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. Publicly available deidentified data were used, and therefore informed consent was not required.

Analysis was performed using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp). Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered significant. Data analysis occurred from August 2017 to September 2018.

Results

Between 2000 and 2015, 16 159 cases of newly diagnosed T1D in in 66 055 000 person-years among children aged 0 to 14 years were recorded by the National Diabetes Services Scheme. This equates to a mean rate of 12.7 (95% CI, 11.0-14.8) cases per 100 000 children.

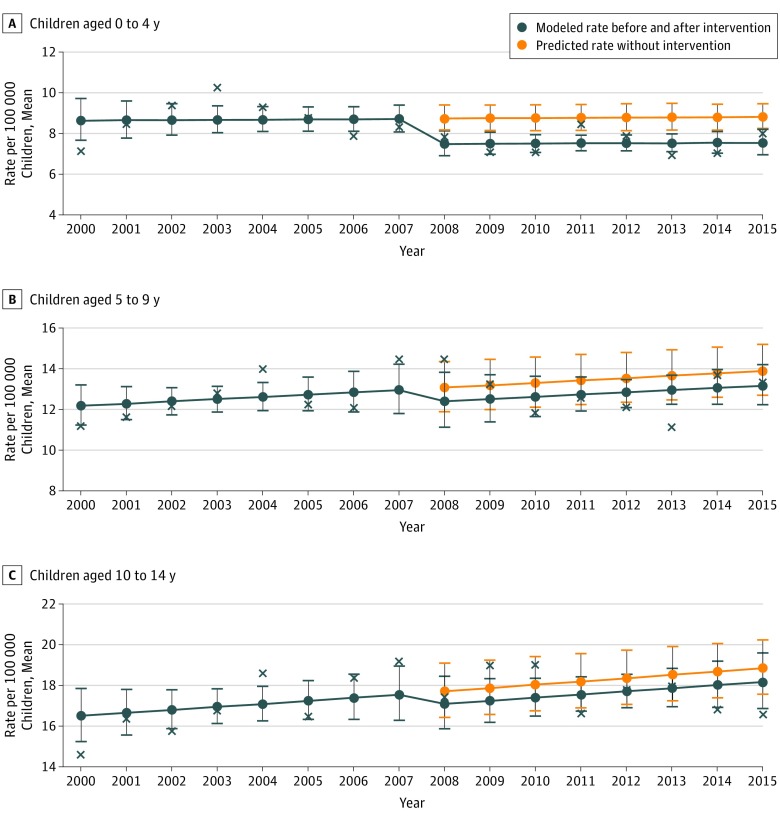

In children aged 0 to 4 years, the number of incident cases of T1D decreased by 14% (rate ratio, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.74-0.99]; P = .04) after the introduction of oral RV vaccine in 2007 (Table). However, there was no evidence of a change over time in the preintervention and postintervention patterns (Figure). In children aged 5 to 9 years and 10 to 14 years, there was no change in the number of incident cases or temporal differences during the entire 16-year period.

Table. Age Group–Based Modeling of Type 1 Diabetes Incidence Rate Ratios Before and After Introduction of Oral Rotavirus Vaccine.

| Age Group, y | Average Rate per 100 000 Children (95% CI) | Modeled Incident Rate Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Modeled | |||

| 0-4 | ||||

| Pre-2008 | 8.7 (7.1-10.2) | 8.6 (7.7-9.7) | 0.85 (0.74-0.99) | .04 |

| Post-2008 | 7.5 (6.9-8.4) | 7.4 (5.9-9.2) | ||

| 5-9 | ||||

| Pre-2008 | 12.6 (11.2-14.5) | 12.2 (11.3-13.2) | 0.95 (0.77-1.17) | .61 |

| Post-2008 | 12.8 (11.1-14.5) | 11.6 (8.9-15.0) | ||

| 10-14 | ||||

| Pre-2008 | 17.0 (14.6-19.2) | 16.5 (15.2-17.9) | 0.97 (0.83-1.12) | .64 |

| Post-2008 | 17.6 (16.6-19.0) | 15.9 (13.0-19.5) | ||

| 0-14 | ||||

| Pre-2008 | 12.8 (7.1-19.2) | 12.6 (10.6-14.8) | 0.93 (0.63-1.37) | .71 |

| Post-2008 | 12.7 (6.9-19.0) | 11.6 (7.1-19.0) | ||

Figure. Age Group–Based Modeling of Type 1 Diabetes Incidence Rate Ratios Before and After Introduction of Oral Rotavirus Vaccine.

Crosses are the observed yearly rates used to fit the modeled rates.

Discussion

Over past decades, the incidence of T1D has consistently increased in Australia3 and worldwide,4 but recent reports, including ones from Australia,5 indicate that the rise may be slowing or even plateauing. We report what is to our knowledge the first evidence of a decline in the incidence of T1D after the introduction of oral RV vaccine into a routine immunization schedule. This occurred in the age cohort of children born after the introduction of RV vaccine and is consistent with the hypothesis that oral RV vaccine may be protective against the development of T1D in early childhood. Ongoing surveillance will determine if the decline in incidence persists as the children advance in age.

In contrast, a Finnish population-based cohort study6 with a relatively small number of cases and a shorter timeframe was inconclusive regarding an association between oral RV vaccination and type 1 diabetes or celiac disease risk. It is possible that response to RV vaccination could vary by geographical location owing to genetic and environmental differences at the population level.

Conclusions

We report what is to our knowledge the first evidence of a decline in the incidence TID after the introduction of oral RV vaccine into a routine immunization schedule. These findings have prompted our team to do a case-control linkage study to further explore the association between RV vaccination and T1D incidence in Australian children.

References

- 1.Honeyman MC, Coulson BS, Stone NL, et al. Association between rotavirus infection and pancreatic islet autoimmunity in children at risk of developing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49(8):1319-1324. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.8.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honeyman MC, Laine D, Zhan Y, Londrigan S, Kirkwood C, Harrison LC. Rotavirus infection induces transient pancreatic involution and hyperglycemia in weanling mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catanzariti L, Faulks K, Moon L, Waters AM, Flack J, Craig ME. Australia’s national trends in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in 0-14-year-olds, 2000-2006. Diabet Med. 2009;26(6):596-601. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EURODIAB ACE Study Group Variation and trends in incidence of childhood diabetes in Europe. Lancet. 2000;355(9207):873-876. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07125-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes A, Bulsara MK, Jones TW, Davis EA. Incidence of childhood onset type 1 diabetes in Western Australia from 1985 to 2016: evidence for a plateau. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(4):690-692. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaarala O, Jokinen J, Lahdenkari M, Leino T. Rotavirus vaccination and the risk of celiac disease or type 1 diabetes in Finnish children at early life. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(7):674-675. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]