Abstract

Background:

The number of older people living and dying with frailty is rising, but our understanding of their end-of-life care needs is limited.

Aim:

To synthesise evidence on the end-of-life care needs of people with frailty.

Design:

Systematic review of literature and narrative synthesis. Protocol registered prospectively with PROSPERO (CRD42016049506).

Data sources:

Fourteen electronic databases (CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, EThOS, Google, Medline, NDLTD, NHS Evidence, NICE, Open grey, Psychinfo, SCIE, SCOPUS and Web of Science) searched from inception to October 2017 and supplemented with bibliographic screening and reference chaining. Studies were included if they used an explicit definition or measure of frailty. Quality was assessed using the National Institute for Health tool for observational studies.

Results:

A total of 4,998 articles were retrieved. Twenty met the inclusion criteria, providing evidence from 92,448 individuals (18,698 with frailty) across seven countries. Thirteen different measures or definitions of frailty were used. People with frailty experience pain and emotional distress at levels similar to people with cancer and also report a range of physical and psychosocial needs, including weakness and anxiety. Functional support needs were high and were highest where people with frailty were cognitively impaired. Individuals with frailty often expressed a preference for reduced intervention, but these preferences were not always observed at critical phases of care.

Conclusion:

People with frailty have varied physical and psychosocial needs at the end of life that may benefit from palliative care. Frailty services should be tailored to patient and family needs and preferences at the end of life.

Keywords: Frailty, palliative care, terminal care, needs assessment

What is already known about the topic?

Frailty is common among older adults and is associated with an increased risk of dying.

Frailty has been proposed as an indicator of need for palliative care.

There is a need to review and collate information on the end-of-life care needs of people with frailty.

What this paper adds?

This study reports that people with frailty have a range of specific physical and psychosocial care needs at the end of life.

A high proportion of people with frailty near the end of life may have significant functional and cognitive impairment, but this hinges on how frailty is defined and measured.

People with frailty are more likely to express a preference for reduced treatment or interventions at the end of life, but these preferences are not always observed at critical phases of care.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

It is important to assess the care needs of older people with frailty who are nearing end of life, with particular attention to pain and emotional distress.

Services for people with frailty nearing end of life should be configured to support needs relating to functional dependence and cognitive impairment and address preferences for care.

Further primary research is needed in community settings and to determine needs earlier in the end-of-life trajectory: measurement of frailty in palliative and end-of-life care research will help to improve our understanding of the care needs of a growing population of older people with frailty.

Introduction

In high-income countries, approximately 11% of people over 65 years, and 25%–50% of those over 85 years, are estimated to be frail.1,2 The number of people living and dying with frailty will rise as the world’s populations age.3 Often defined as a state of increased vulnerability to stressors, frailty is characterised by an accumulation of deficits, diminished strength and endurance, and reduced physiological function.4,5 Frailty increases the risk of adverse outcomes, including falls, delirium, and disability and mortality.6–10

There are few specialist end-of-life services for frailty, despite its high prevalence in older people, and suggestions that frailty should signal a need to adopt a palliative care approach.11,12 Many established palliative care pathways were designed to meet the needs of people with cancer, and it is unclear how appropriate these are for people with frailty.13,14 Recent work in England found that older people, carers and other key stakeholders agree that work is needed to develop a model of supportive and palliative care for people with frailty.15 Symptom management (encompassing physical and psychosocial distress) was identified as a vital component of such services. However, people with frailty are a heterogeneous group. Some live with functional or sensory impairments and experience a slow downwards health trajectory without major life-limiting diagnoses. Others have multiple medical conditions that trigger access to specialist care. Understanding the needs of people with frailty who are nearing end of life is fundamental to providing appropriate care and support,1 and is also a step on the path to addressing the question of which core palliative care services should be provided for all, irrespective of diagnosis.16 Population-based needs assessments for palliative care in other disease groups have been carried out using population level mortality records combed with data on symptom prevalence, disease prevalence or service utilisation.17 However, to date, evidence of specific needs for either general or specialist palliative care among people with frailty is limited. This review aims to contribute to identifying and defining this evidence gap, by synthesising evidence on palliative care needs of people dying with frailty.

Methods

We sought to systematically identify literature on people with frailty nearing end of life and synthesise evidence on their needs for care. A study protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (2016 – CRD42016049506). To identify academic publications and grey literature, 14 electronic databases were searched (CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, EThOS, Google, Medline, NDLTD, NHS Evidence, NICE, Open grey, Psychinfo, SCIE, SCOPUS and Web of Science) from the earliest index date to October 2017, using tailored strategies developed by an information scientist (Supplemental information A). We searched for literature on older adults with frailty who were nearing end of life or were receiving palliative treatment. These searches were supplemented with hand screening of bibliographies and reference lists, citation searches and targeted searches of key authors’ work. Title and abstract screening were completed independently by two authors to identify studies for inclusion in the review. The full texts of these studies were retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility by the lead author in discussion with another co-author (G.S.).

Study inclusion criteria

Studies were included where they reported quantitative data from individuals nearing the end of life (study author defined), or where study authors stated people with frailty were receiving care in a palliative care setting, or with stated advanced, or terminal illness or decline.18 We adopted the UK General Medical Council’s definition of end of life19 and the World Health Organisation’s definition of palliative care (Supplemental information B).20 Qualitative research studies were not included, but no other restrictions were placed on the study designs eligible for inclusion, and studies were not excluded on the basis of publication language, type or status. We did not exclude studies based on the date of data collection or publication. Editorials and opinion pieces were excluded. To produce evidence relevant for healthcare systems in the United Kingdom and those similar to those of the United Kingdom, studies where data were not collected in high-income counties (defined by the World Bank) were excluded.21

Participant inclusion criteria

Frailty is associated with increasing age, but no upper or lower limits were set on the age of participants eligible for inclusion in the study. Studies were excluded where ‘frail’ was used as a synonym for old without justification, or where the term frailty was used without the authors defining frailty or their frail participants. Frailty could be defined using phenotypic, cumulative deficit or other operational definitions of frailty (that may integrate demographic, clinical, psychological and functional information). The definition or measure of frailty was accounted for in the narrative synthesis. Studies were included where participants were identified as nearing end of life or where palliative care needs were discussed directly. Studies were not excluded on the basis of the presence of co-morbidities.

Outcome measures

The aim of the review was to synthesise the evidence on end-of-life care needs in people with frailty. Health need has been broadly defined as the capacity to benefit from healthcare.22 We adopted a broad approach to identifying and classifying end-of-life care needs, based on this definition of need. We included work that discussed various domains including physical symptoms, psychological, emotional, functional (and social) needs for support, in common with previous work on palliative care needs.17 Data were extracted by the lead author using a data extraction form.

Evidence synthesis

Due to heterogeneity in the study designs, settings and measurements, there were no data suitable for pooling and a narrative synthesis was conducted according to guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.23 A narrative structure was developed to best fit the data, using categories established in previous work on palliative care needs,17 and cross checked using Bradshaw’s taxonomy of need.24 We considered care needs in terms of normative needs (where a health professional stated a need was present), felt needs (where people with frailty or their relatives perceived or reported a need, for example, feeling pain), expressed need (where individuals have made a demand, for example, accessing care as a result of a felt need) and comparative need (where the needs of people with frailty were compared to groups of people near end of life with other diagnoses).

Quality assessment and risk of bias

Risk of bias and quality of included studies were assessed by the lead author using the National Institute for Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.25 Low-quality studies were excluded from the summary of evidence table, but were discussed in the narrative synthesis.

Results

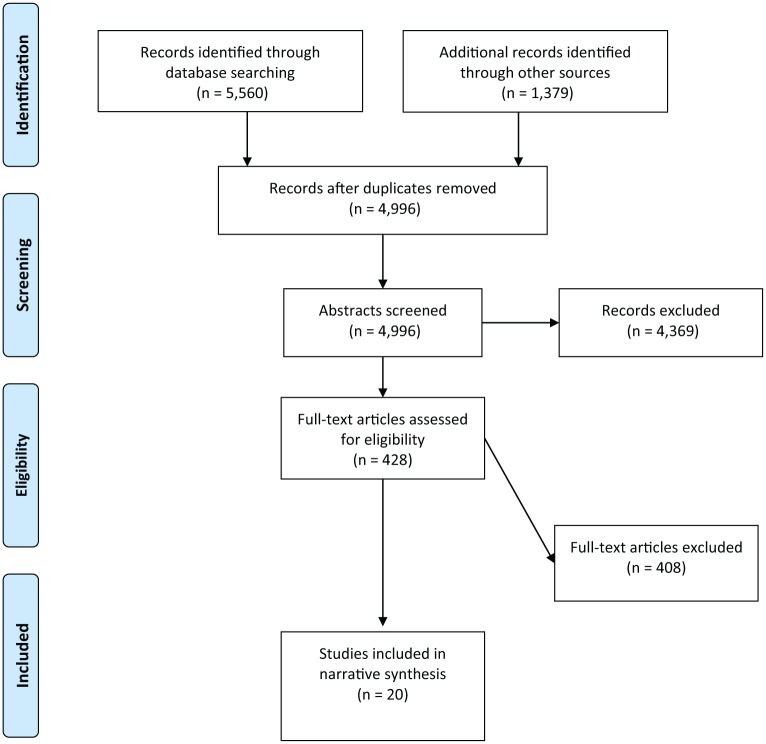

The searches identified 4,997 non-duplicate studies, of which 4,799 were excluded at the title and abstract screening phase. After reviewing the titles and abstracts of the remaining 198 studies, 20 articles met the criteria for inclusion in this review.26–44 Figure 1 shows the paper inclusion process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing study screening and selection process.

Study characteristics

The 20 included studies reported evidence from 92,448 individuals (18,698 with frailty) across seven high-income countries (Canada = 6, United States = 6, Spain = 3, Netherlands = 2, Japan = 1, Singapore = 1, United Kingdom = 1). Sample sizes ranged from 40 to 57,753 participants (23–9935 with frailty). Fourteen studies used a cross-sectional design,26–31,34,36–38,40–42,44,45 five were prospective cohort studies,31,33,35,39,43 and one was a case–control study.45 A majority of studies (13 out of 20) reported data from hospital settings only, four from multiple settings including hospitals, hospice facilities and long-term care,27,28,30,32 and three across multiple settings, including the community.34,39,43 Using the National Institute for Health quality assessment tool, nine studies were classified as good, six as fair and five as poor quality. Characteristics of included studies are summarised in Table 1 and a detailed quality assessment table may be found in Supplemental information C.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the review.

| Citation | Country | Setting | Population | End-of-life definition | Design | Frailty definition classification | Total sample | Number of frail participants | Summary of findings | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amblas-Novellas et al.27 | Spain | Three selected primary care services, an acute care hospital, an intermediate care centre and four nursing homes in a mixed urban–rural district in Barcelona | People identified as requiring palliative care using a palliative care screening tool | Study defined: people with a positive NECPAL result indicating they might benefit from a palliative approach (includes ‘no’ to the ‘surprise question’) | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 782 | 377 | Compared to people with cancer, healthcare professionals were less likely to think people with frailty had palliative care needs. People with frailty had greater levels of functional impairment, and a similar proportion experienced emotional distress, pressure ulcers, falls and delirium | Fair |

| Bagshaw et al.35 | Canada | Intensive care units at two tertiary care hospitals and four community hospitals in Alberta | People admitted to an ICU who were expected to survive and stay for longer than 24 hours | 43% of frail group died within 6 months following study start | Prospective cohort study | Cumulative deficit | 421 | 138 | Compared to people who did not have frailty, those with frailty had greater functional dependence and had less social support at admission to ICU. People with frailty were more likely to have a limitation of medical therapy order in place on admission, but were no less likely to receive intensive treatment | Good |

| Chibnall et al.41 | United States | Internal medicine department, Saint Louis University Health Sciences Centre, or, oncology outpatient service at Forrest Park Hospital, Missouri | People from oncology, pulmonary cardiac, infectious diseases, general internal medicine, geriatric medicine and outpatient services | Study defined: people who were expected to live at least 6 months but whose prognosis supported a consideration of life/death issues | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 67 | 23 | The study sample size was too small for predictive modelling, but there was no evidence of a strong correlation between geriatric frailty and death distress | Poor |

| Chochinov et al.28 | Canada | Hospitals, outpatient clinics inpatient facilities or personal care homes in Winnipeg, Manitoba and Edmonton, Alberta | People with Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), end-stage renal disease (ESRD) recruited from outpatient clinics and inpatient facilities. Frail participants classed as residents of personal care homes, aged 80+ years | Study defined: people whose current clinical status suggested imminently life-limiting circumstances, hence most likely to benefit from a palliative care approach | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 404 | 102 | People with frailty had a higher number of ADL dependencies, the lowest levels of hope and the highest desire for death compared to people with ALS, COPD and ESRD. All diagnostic groups experienced similar levels of pain, nausea, drowsiness, constipation, difficulty thinking, will to live and wellbeing | Good |

| Covinsky et al.43 | United States | Community settings across 12 demonstration sites (across 8 US states) for a Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) | People age over 55 who would be eligible for nursing home placement according to their home state’s criteria | Data collected during the last 2 years of life for all participants | Prospective cohort | Other operational definitions of frailty | 917 | Cognitively impaired: 583 Non-cognitively impaired: 334 |

People with frailty become gradually more functionally impaired over the last 2 years of life. People with frailty (and with cognitive impairment) are more functionally impaired than people with frailty (without cognitive impairment) | Good |

| Ernst et al.45 | United States | Surgical units at Nebraska Western Iowa Veterans Affairs Medical Center | People who received a palliative care consultation and did not undergo the associated surgical procedure | People receiving palliative consultations: 66%–79% died within 1 year of consultation | Case control | Other operational definitions of frailty | 310 | 310 | After implementing a frailty screening programme, more people received a palliative care consultation and were less likely to undergo surgical procedures. This lead to a decrease in mortality whether the patient had surgery or not | Good |

| Heyland et al.33 | Canada | Intensive care units in 24 hospitals in Quebec, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Ontario, British Columbia and Manitoba | People age 80 or older admitted to ICU | Sample at high risk of death (over 80 in ICU) – 20% of sample died within 7 days of admission, 13% died after 7 days | Prospective cohort study | Cumulative deficit | 610 | 193 | People with frailty were more likely to have a limitation of treatment order at admission to ICU and were less likely to undergo mechanical ventilation. But people with frailty were as likely as people who were not frail to receive other life-sustaining treatments | Fair |

| Heyland et al.29 | Canada | 16 acute care hospitals in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec | Hospitalised people (a) age 55–79 years with advanced pulmonary, cardiac or liver disease, metastatic cancer, or (b) age 80+ years admitted for an acute medical or surgical condition or (c) any patient whose death within the next 6 months would not surprise any member of the care team | Inclusion criteria for study are people with advanced terminal illness, people at high risk of dying or people whose death within 6 months would not surprise a member of their care team | Cross-sectional | Cumulative deficit | 808 | 280 | People with frailty were more likely to have their documented preferences for resuscitation reflected in documented goals for care | Good |

| Hofstede et al.30 | Netherlands | Hospitals, hospices, residential elderly care and homecare settings enrolled in the Dutch National Quality Improvement Programme for Palliative Care | Bereaved relatives of individuals who died March 2013–June 2014 | Study asking relatives about quality of end-of-life care for people who had died, including care provided in the last week of life | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 456 | 180 | Compared to people with cancer, family rated quality of end-of-life care in the last week of life was lower for individuals with frailty. People with frailty were less likely to have access to a spiritual counsellor | Good |

| Huijberts et al.31 | Netherlands | 5 Wards in The Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam (a university teaching hospital) | People (acutely) admitted to hospital for over 48 hours | All study participants died within 1 year of study index admission | Prospective cohort study | Other operational definitions of frailty | 306 | 57 | Compared to people with cancer and end-stage organ failure, people with frailty had more limitations to ADL and were more likely to be cognitively impaired. People with frailty were less likely to have advance care-planning information in their records, but where present, the recorded goals of care were similar to those of people with cancer and end-stage organ failure | Fair |

| Ikegami and Ikezaki38 | Japan | Six non-psychiatric hospitals in Kamogawa city | Family members of adult people who died in hospital during the first half of 2008 | Study asking family members about care provided on the day their relative died | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 205 | 40 | People with frailty were as likely as people with cancer to have their preferences for end-of-life care followed by a physician and were no more likely than individuals with cancer to receive any form of life-sustaining treatment contrary to preferences | Fair |

| Lavergne et al.34 | Canada | Three (of nine) health districts in Nova Scotia (two urban and one rural) | Adult residents in three district health authorities who died between 2003 and 2009, not in a nursing home | Outcome measure is place of death and palliative care programme enrolment | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 23860 | 5117 | People with frailty were less likely to be enrolled in a palliative care programme, and had a lower risk of dying in a hospital | Good |

| Moorhouse and Mallery37 | Canada | A tertiary care centre associated with the Division of Geriatric Medicine at Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia | Adults age 65 and over with: advanced or progressive illness; progressive decline in physical or cognitive function; or multiple hospital admissions, referred to the PATH program (a trial of a decision-making and care-planning pathway) | Study defined – the PATH programme is for people considered to be at end of life | Cross-sectional | Cumulative deficit | 150 | 150 | Higher levels of frailty were associated with an increased likelihood of not accepting a scheduled intervention or treatment | Fair |

| Munoz and Martin40 | Spain | One long stay hospital in Castellon | People in a hospital palliative unit aged 75–93 years | Participants are in a palliative unit and considered to be end of life (study defined) | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 40 | 40 | People with frailty reported a range of symptoms. The most common symptoms were difficulty breathing (45%), loss of appetite (37.5%), weakness (30%), insomnia (27.5%), hearing problems (25%), pain (22.5%), weight loss (20%) and sadness (20%) | Poor |

| Pollack et al.42 | United States | One urban tertiary care hospital and one community hospital in New York | Individuals age 65+ admitted to ICU for acute respiratory failure requiring more than 24 hours of mechanical ventilation | Study discusses end-of-life care preferences of people at high risk of death – 21% of people with frailty died within 3 months following index admission | Cross-sectional | Phenotypic | 125 | 107 | Frail survivors of mechanical ventilation had higher physical and emotional symptom distress scores compared to non-frail survivors | Fair |

| Ryan et al.36 | United Kingdom | All inpatient wards (except maternity units) of two English hospitals (one rural, one urban) | People in any ward (except children’s wards and mother and baby units) age over 18 fulfilling one of 11 Gold Standards Framework (GSF) prognostic criteria that indicate where a patient might benefit from palliative care | Study defined end of life based on GSF prognostic criteria | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 249 | 49 | Frailty status did not predict global physical symptom burden but there was limited evidence of an association between frailty and global psychological burden | Poor |

| Smith et al.39 | United States | Data taken from the Health and Retirement study (HRS): a national area population level study | People who died while enrolled in the HRS study and who provided information about the presence of pain in an interview within 2 years of death | Pain measured 2 years, 1 year, 4 months prior to death and in the last month of life | Prospective cohort study | Other operational definitions of frailty | 4703 | 555 | For people with a terminal diagnosis, the prevalence of pain among people with frailty is similar to those with cancer 2 years, 1 year, 4 months and 1 month prior to death | Good |

| Soto-Rubio et al.26 | Spain | Two hospital palliative care units | People in hospital palliative care units | Study defined end of life – all participants were in a palliative care unit | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 85 | Cognitively impaired: 45 Non-cognitively impaired: 40 |

Many people with frailty have cognitive impairment and functional dependence. Regardless of cognitive status, people with frailty have high levels of emotional distress | Poor |

| Wachterman et al.32 | United States | 146 Veterans Affairs facilities across the United States | People (and family members of people) and who died in 1 of 146 veteran affairs facilities across the Unites States between October 2009 and October 2012 | All study participants had died – family members were asked about quality of care in the last 90 days of life | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 57,753 (34,005) |

9,935 (8,538) |

Compared to people with cancer, people with frailty were less likely to have received a palliative care consultation in the last 90 days of life, have a do not resuscitate (DNR) order in place at time of death, or die in an inpatient hospice. Family reported quality of end-of-life care was significantly worse for people with frailty, but this quality advantage was mediated by palliative care consultation, DNR order, and place of death | Good |

| YashPal et al.44 | Singapore | The emergency department of the National University Hospital, Singapore | People age 65 and over who died in the emergency department over 1 year | All participants died during admission to an emergency department | Cross-sectional | Other operational definitions of frailty | 197 | 43 | Compared to people with cancer, a lower number of people with frailty had recorded preferences for resuscitation, and a higher number received aggressive resuscitation | Poor |

ADL: activities of daily living.

Thirteen different definitions or measures of frailty were used in the 20 articles (Table 2). One study each used: modified Fried criteria,6 a study-specific risk analysis index (RAI),45 the Gold Standards Framework criteria for frailty46 and NECPAL (Necesidades Paliativas) criteria (requiring palliative care with no major diagnosis).47 One study cited frailty trajectories from Lynn and Adamson,48 a definition that requires functional impairment due to dementia or other causes. Another study used specific symptoms or diagnoses to identify frailty, including Parkinson’s disease, hip fracture and incontinence.32 Four studies used the Clinical Frailty Scale49; two studies used a definition from Botella and colleagues.50 Four studies cited the trajectories of functional decline described by Lunney and colleagues51 and went on to specify additional criteria for inclusion in their studies. All four of these studies included a diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment in their frailty criteria, and two also included being resident31 or dying39 in a nursing home. Four additional studies employed their own specific definitions of frailty: limited life expectancy due to advanced age and comorbidities41; age, care home residence, needing support with activities of daily living (ADLs) and cognitive impairment28; age⩾55 and eligible for nursing homecare according to their state’s guidelines43; people who were bed bound and had cognitive impairment.44

Table 2.

Definitions and measures of frailty used by studies in the review.

| Frailty definition or measurement source | Studies using measure or definition | Study country | Study-specific frailty definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botella et al definition50 | Munoz and Martin40

Soto-Rubio et al.26 |

Spain | Being an elderly person (over 75 years of age), with the presence of numerous chronic diseases (multiple pathology) or geriatric syndrome (incontinence, falls, cognitive impairment, immobility, etc.) |

| Clinical Frailty Scale49 | Bagshaw et al.35

Heyland et al.29 Heyland et al.33 Moorhouse and Mallery37 |

Canada | Measured using the Clinical Frailty Scale – 9° of frailty from very fit to terminally ill. Scale degrees categorised by extent of functional impairment |

| Fried criteria6 | Pollack et al.42 | United States | Modified fried frailty assessment (for older adults in ICU): frailty defined by the presence of three or more of the following: shrinking, weakness, slowness, low physical activity, exhaustion |

| Gold Standards Framework (GSF) frailty criteria46 | Ryan et al.36 | United Kingdom | GSF criteria for frailty: individuals who present with multiple comorbidities, with significant impairment in day-to-day living and: deteriorating functional score (e.g. performance status – Barthel/ECOG/Karnofksy) and a combination of at least three of the following symptoms, weakness, slow walking speed significant weight loss, exhaustion, low physical activity |

| Lunney Trajectories51 | Hofstede et al.30 | Netherlands | Individuals with dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease or hip fracture and with age ⩾ 65 years |

| Huijberts et al.31 | Netherlands | Frail patients are those without cancer or end-stage organ failure and either resident in nursing home or sheltered accommodation, or patients with MMSE < 25 and Katz ADL (activities of daily living) index > 7 | |

| Lavergne et al.34 | Canada | Dementia, Parkinson’s disease, infections, weight loss, osteoporosis | |

| Smith et al.39 | United States | When death occurred in nursing home, after hip fracture in last year of life, or with physician diagnosed memory impairment | |

| Lynn and Adamson Trajectories48 | Ikegami and Ikezaki38 | Japan | Frailty trajectory from Lynn and Adamson ‘individuals who are old and where daily life has become difficult due to cerebro-vascular disability, dementia or other causes, and, moreover, the general condition has greatly deteriorated’ |

| Necesidades Paliativas (NECPAL) screening tool47 | Amblas-Novellas et al.27 | Spain | No advanced disease criteria (cancer, organ failure) and at least two of the following: pressure ulcers, infections, dysphagia, delirium, falls |

| Risk analysis index (RAI) – study-specific screening tool45 | Ernst et al.45 | United States | The RAI was developed for use with surgical patients to identify frail individuals. It includes comorbidities, functional impairment and cognitive decline. Scores range from 0 to 75, ⩾ 21 is frail |

| Study-specific diagnoses | Wachterman et al.32 | United States | Parkinson’s disease, stroke, hip fracture, delirium, pneumonia, incontinence, dehydration, leg cellulitis or syncope |

| Study-specific definition | Chibnall et al.41 | United States | Limited life expectancy due to advanced age plus a heavy burden of co-morbid conditions, no one of which was directly life threatening on its own |

| Study-specific definition | Chochinov et al.28 | Canada | 1. Over 80 years of age 2. In a personal care home 3. Requiring assistance with two or more basic ADL 4. Cognitive Performance Scale of 0–3 |

| Study-specific definition | Covinsky et al.43 | United States | 1. Over 55 2. Eligible for nursing home placement according to their state’s criteria |

| Study-specific definition | YashPal et al.44 | Singapore | Patients who were bed-bound or had cognitive impairment |

MMSE: mini-mental state examination; ECOG: eastern cooperative oncology group scale of performance status.

Palliative care needs

A wide range of potential palliative care needs and outcomes were reported across all 20 studies, encompassing the following domains: physical health (symptom burden and specific mental symptoms), psychosocial needs, functional status, care-related outcomes (including place of death and satisfaction with care) and preferences for care. Table 3 contains a summary of findings from good and fair quality studies only. Prevalence ranges are presented where available and the table summarises the number of studies where people with frailty had a greater (+), similar (=) or reduced (–) need compared to groups of people with other diagnoses. This comparative need was defined using the author’s judgement according to symptom prevalence or mean/median scores on measurement instruments. Some studies compared multiple diagnostic groups. For a detailed account of the data summarised, please see Supplemental information D.

Table 3.

Summary of evidence of needs in people with frailty and comparison to other diagnostic groups.

| Needs domain | Total number of studies for each need | Summary of prevalence estimates for people with frailty (range) | Summary of the number of studies showing that people with frailty had a greater (+), similar (=) or lower (–) need compared to other diagnostic categoriesa |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Non frail | ALS | COPD | ESRD | Organ failure | Dementia | |||

| Physical symptoms | |||||||||

| Pain | 4 | 30.0%–52.3% | =– | = | = | = | = | ||

| Nausea | 2 | - | = | = | = | = | |||

| Drowsiness | 2 | - | = | = | = | = | |||

| Shortness of breath | 2 | - | = | – | – | – | |||

| Fatigue/weakness | 2 | - | + | – | – | – | |||

| Constipation | 1 | - | = | = | = | ||||

| Difficulty thinking | 1 | - | = | = | = | ||||

| Loss of appetite | 1 | - | = | ||||||

| Pressure ulcers | 1 | - | – | + | = | ||||

| Psychosocial needs | |||||||||

| Composite emotional distress | 2 | 23.8% | = | + | = | = | |||

| Anxiety | 2 | - | + | – | – | – | |||

| Poor wellbeing | 2 | - | + | = | = | = | |||

| Depression | 1 | - | + | ||||||

| Low social support | 1 | - | + | + | + | ||||

| Hopelessnessb | 1 | - | + | + | + | ||||

| Hopelessnessb | 1 | - | = | = | = | ||||

| Desire for death | 1 | - | + | + | + | ||||

| No will to live | 1 | - | = | = | = | ||||

| Loss of dignity | 1 | - | = | = | = | ||||

| Suffering | 1 | - | = | = | = | ||||

| Suicidal | 1 | - | =– | = | – | ||||

| General dissatisfaction | 1 | - | = | = | = | ||||

| Functional status | |||||||||

| Functional dependence | 9 | 10.6%–73.9% | ++ | += | + | + | + | ++ | – |

| Place of death | |||||||||

| ICU | 2 | 11.6%–33.2% | + | + | |||||

| Hospital (non ICU) | 4 | 10.0%–31.9% | +– | +– | |||||

| Nursing home | 2 | 14.7%–79.0% | +– | + | |||||

| Hospice | 2 | 0.0%–20.8% | – | ||||||

| Home | 1 | 8.0% | – | ||||||

| Satisfaction/access | |||||||||

| Family-rated relative’s care as good | 2 | 54.8% | – – | ||||||

| Received care in line with preferences | 4 | 75.0% | + | +– – | |||||

| Preferences for care | |||||||||

| Comfort-oriented care | 1 | 81.0% | = | ||||||

| No CPR | 1 | 61.0% | = | ||||||

| Restricted treatment | 1 | 48.4%–72.9% | = | = | |||||

| Palliative approach (patient-expressed choice) | 1 | 5.6% | – | = | + | ||||

| Palliative approach (family-expressed choice) | 1 | 21.5% | – | – | |||||

| No treatment (including scheduled surgical procedures) | 3 | 38.5% | + | ||||||

ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD: end-stage renal disease.

Each symbol reflects a single study result and refers to prevalence of need or mean/median scores on measurement instruments relative to the diagnostic comparator group. Some studies compared multiple diagnostic groups.

Hopelessness was measured in two ways by one study that compared people with frailty to people with ALS, COPD and ESRD. Using the Herth Hope Index, people with frailty had the least hope. Using the hopelessness item from the Structured Interview of Symptoms and Concerns, similar numbers of people scored 3 or more for hopelessness (range 0–6) in each group.

Physical health

Seven studies detailed 32 physical symptoms in people with frailty nearing end of life: three good quality,28,32,39 two fair quality27,42 and two poor quality.36,40 One study, of poor quality, examined a composite measure of burden of physical symptoms in people with frailty and reported it to be higher than in those with cancer.36 Evidence from two good quality studies suggested that pain in people with frailty is similar in prevalence to pain in people with cancer: increasing from 30% 2 years prior to death to 50% during month of death in a longitudinal study39 and 53% experienced (via family reports) uncontrolled pain in another large cross-sectional study examining the final phase of life.32 Pain also caused distress in people with frailty to a similar degree as people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD).28 There was weak evidence that people with frailty experience similar levels of pain to non-frail individuals in critical care42 and one poor quality, non-comparative study reported that 23% of frail individuals in a palliative unit reported a lot of problems with pain.40

Evidence was mixed for the occurrence of other physical symptoms including shortness of breath (less problematic than for COPD or ALS,28 but more problematic than non-frail,42 poor quality evidence estimating 45% prevalence40); drowsiness (higher than in non-frail,42 but less so than ALS, COPD and ESRD28); fatigue/weakness (less problematic than for COPD or ALS,28 but more problematic than non-frail,42 with poor quality evidence of 30% prevalence40); loss of appetite (similarly problematic to non-frail,42 with poor quality evidence of 38% prevalence40) and pressure ulcers (similarly problematic to dementia, but lower than for cancer27). There was poor quality evidence from a non-comparative study that two-fifths or more people with frailty have problems with weakness, sleeplessness, insomnia and loss of weight.40 Compared to people who were not frail and people with ALS, COPD and ESRD, people with frailty experience similar, low levels of nausea, constipation and problems thinking.27,41 There was poor quality, non-comparative evidence that people with frailty do not have problems with nausea, sight or speech problems, cough, oral discomfort/pain when swallowing, rectal/urinary incontinence, poor concentration, itchiness, paralysis, diarrhoea, haemorrhage or irritability.40

Psychosocial needs

Seven studies examined the psychosocial needs of people with frailty nearing the end of life, one of good quality,28 two fair27,42 and four poor quality.26,36,40,41 There was evidence that people with frailty experience similar study defined ‘emotional distress’ (emotional distress with psychological symptoms that are sustained, intense, progressive and not related to acute concurrent conditions) to people with cancer from one fair quality study.27 Another, poor quality study found people with frailty experience similar study defined ‘psychological burden’ (a composite of responses to a range of questions including items about anxiety, low mood confusion and loneliness) compared to people with cancer.36 Compared to people with ALS, COPD and ESRD, people with frailty had the lowest perceived social support, the lowest levels of hope and the highest desire for death, similar wellbeing, will to live, losses of dignity, suffering, hopelessness and dissatisfaction, but did not feel suicidal and were less anxious.28 Compared to non-frail individuals, one fair quality study found that people with frailty experience greater anxiety, depression and loss of wellbeing towards the end of life.42

One poor quality study found no significant correlation between frailty and ‘death distress’ (a construct that incorporates death anxiety: death-related fear, obsessiveness, nervousness, arousal; and death depression: death-related feelings of sadness, dread, meaninglessness and lethargy)41 compared to mixed disease and HIV/AIDS groups, but noted that death distress was correlated with depression within the frail group. The authors suggested that for people with frailty, death distress might reflect a general psychological burden (including depression and anxiety) at recognising they are nearing the end of life, but without a specific life-threatening diagnosis.41

Two studies described psychosocial needs of people in palliative care units in Spain without any comparison. One26,52 reported that 42% of people with frailty (with cognitive impairment) experienced high levels of emotional discomfort (where five or more of nine behavioural indicators from the authors’ Discomfort Observation Scale were observed)26 and 25% of people with frailty (without cognitive impairment) experienced ‘emotional distress’ (scoring higher than 20 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale50). The other40 reported sadness, loneliness and nervousness in over 10% of the people with frailty and evidence that people with frailty do not have any concerns about odour, appearance or spiritual matters.

Functional status

Seven studies discussed the functional status of frail individuals nearing end of life: two good quality,28,35 four fair27,31,42,43 and one poor quality.26 Comparisons of functional status between people with frailty and those living with other diagnoses were complicated by the varied approaches to the definition of frailty. Levels of functional impairment among people with frailty were reported to be higher than cancer patients in two studies.27,31 One of these studies excluded dementia patients from the frail group,27 and the other defined people with frailty as individuals living in a nursing home or with a mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score < 24.31 Compared to the non-frail, frail individuals were found to be significantly more functionally impaired in a good quality study that did not report any measure of cognitive function (or explicitly exclude people with dementia).35 Another fair quality study excluded people with dementia, and people with frailty were more likely to be cognitively impaired, and had more impaired ADL than the non-frail.42 In a fair quality US study examining longitudinal trajectories of frailty, people with frailty (with cognitive impairment) were three times more likely to become fully dependent on assistance with bathing, eating and mobility and continence than non-cognitively impaired people with frailty. Over the course of the last 2 years of life, both groups exhibited a decline in functional independence and 9–12 months prior to death 84%, 20%, 46% and 31% of people with frailty (without cognitive impairment) were fully dependent on assistance with bathing, eating, mobility and continence, respectively.43

People with frailty were more functionally impaired than individuals with ALS, COPD and ESRD, although in this study, the frail group was defined by more than two ADL dependencies.28 One poor quality non-comparative study reported that almost two-thirds (62.5%) of people were functionally dependent. Here, half of the frail group had cognitive impairment.26

Place of death

Four good quality studies recorded place of death.30,32,34,35 The discussion of place of death is complicated by two factors: (1) place of death as a quality outcome is related to patient preference, but none of these studies compare preference with outcome; (2) variation in place of death may be attributable to the national differences in healthcare systems. In Canada, people with frailty were more likely than non-frail individuals to die in hospital following an intensive care unit (ICU) admission,35 but in a population level study were less likely to die in hospital than individuals with a terminal diagnosis.34 In the United States (considering Veterans’ Affairs facilities only), people with frailty were more likely than cancer patients to die in a hospital or ICU than in a nursing home or hospice.32 In the Netherlands,30 the majority (79%) of people with frailty died in a nursing home, whereas the majority of cancer patients died in individual homes (53%).

Satisfaction and access to care

Seven studies reported data on satisfaction with, or access to care (five good29,30,32–35,38 and two of fair29,38 quality). Studies from the Veterans Affairs facilities in the United States32 and from mixed settings including care homes and hospitals in the Netherlands30 found that families’ general satisfaction with end-of-life care provided to people with frailty was significantly lower than for those with cancer. The US study32 and another Canadian population level study34 found that people with frailty were less likely to access palliative care than people with cancer. The US study also reported that palliative care consultation status and place of death mediated families’ reported satisfaction with the end-of-life care for people with frailty. This was not reported for families of cancer patients.

Evidence from Canada on whether care provided for frailty was in line with peoples’ preferences is mixed. One cross-sectional study with hospital patients found that those with frailty were more likely than non-frail patients to have recorded goals for care in line with their stated preference.29 Two further Canadian studies (one from the same author) ascertained actual treatment outcomes.33,35 They found that people with frailty were more likely than people who were not frail to have a limitation of treatment order in place at admission to ICU, but there was no differences in the proportions who received intensive or life-sustaining treatment, with the exception of mechanical ventilation in one of the two.33 One fair quality study, based in hospitals in Japan, found limited evidence that more people with frailty than with cancer (75.0% vs 52.7%) had their preferences for life-sustaining treatment followed by physicians. These differences may be due to the differences in methods of communicating preferences in different health systems and environments.

Preferences for care

Six studies (one good45 and five fair27,31,37,38,42 quality) contained information on preferences for care. All of the studies were based on critically ill people in hospitals and concerned patient or family reported preferences for treatment or treatment intensity. Compared to people with cancer, the evidence was mixed. In the Netherlands, people with frailty were as likely as people with cancer to have treatment restrictions in place following advance care planning during hospitalisation.31 In a Spanish study, of people identified as requiring palliative approach with the NECPAL screening tool, people with frailty (5.6%) and their family members (21.5%) were less likely than people with cancer (17.1%, 39.5%, respectively) to have also requested a palliative approach (although they were as likely to request a palliative approach as people with organ failure).27 In Japan, 38.5% of family members of people who died with frailty reported that their family member did not want life-sustaining treatment in any form versus 23.2% (p = 0.092) for cancer.38

Compared to people of a similar age but who were not frail, individuals with frailty were often reported to prefer less invasive or intense treatment: One Canadian study found that during a trial of a palliative care pathway, people with frailty were more than three times more likely than people without frailty to decline a scheduled treatment or procedure (odds ratio (OR) 3.41; 9% confidence interval (CI) 1.39–8.38).37 In a study from the United States, following the introduction of a frailty screening programme, palliative consultations were more likely to occur prior to surgical intervention. This led to an increase in the number of patients declining surgery (5.6% declined pre-implementation vs 19.3% post).45 In another study from the United States,42 people with frailty were not significantly more likely than those who were not frail to request comfort-oriented care (81% vs 71%, p = 0.31) or no resuscitation (11% vs 21%, p = 0.35) after ICU admission. One poor quality study from an emergency department at a hospital in Singapore reported limited evidence that fewer people with frailty than with cancer (20.9% vs 30.8%) had a pre-existing resuscitation status but more people with frailty than with cancer (60.5% vs 46.2%) received aggressive resuscitation in the emergency department before dying.44 This observation was reversed in a comparison with people with organ failure (20.9 vs 2.2% and 60.5% vs 95.6%, respectively).

Discussion

Main findings

To our knowledge, this is the first review to synthesise the available evidence on the specific palliative care needs of people with frailty at the end of life. We found that people with frailty nearing end of life experience a range of normative, felt and expressed needs across both physical and psychosocial domains. We have also demonstrated a comparative need for end-of-life care, as many of these needs are similar in frequency and nature to those experienced by people with other recognised terminal diagnoses. Notably, pain and some forms of emotional distress were present to a similar extent as people with terminal cancer.

Comparison with other work

This study adds to growing reports of an association between frailty and pain.53,54 The mechanisms underlying pain at the end of life are multi-dimensional and pain is known to be common in many advanced and/or progressive diseases. Management of pain is a key feature of many palliative services18; however, it is often poorly assessed and managed at the end of life.55 Recent work has projected future palliative care needs based on a review of pain prevalence in people with cancer (84%), organ failure (67%) and dementia (60%) during the last year of life.56 These prevalence estimates are higher than the range of estimates (10%–52%) reported in the present review for people with frailty.

For many older adults, physical and cognitive frailty coexists,57 and our findings suggest that towards the end of life, a high proportion of people with frailty are cognitively impaired and have needs for functional support. However, it is difficult to draw any inferences on the level of support needs, as a number of studies included functional impairment or dementia as part of the criteria for identifying frailty.

Community-based services provide the majority of care for people living with frailty and two recent reviews have affirmed the role that primary care plays in providing end-of-life care.58,59 The first, reporting patient and carer perceptions, suggests that general practitioners (GPs) are well placed to understand the end-of-life needs for people with frailty and should be a focus for communication between specialist services.58 The second review identified barriers to providing emotional support, deficiencies in pain management and limited evidence that GPs are comfortable managing depression in palliative care patients.59

Our review highlights potential inequities in access to specialist palliative care, as people with frailty were reported to be less likely to access specialist services or to die in a hospice. Whether this is appropriate, or reflects limited service provision for people with frailty, or lack of professional awareness of their needs, is unclear. One study included in our review controlled for age in their analysis, suggesting that frailty was associated with reduced access to care independent of age.32 However, previous research has also shown that increasing age on its own is associated with reduced access to specialist palliative care and lower likelihood of death in a hospice.60

The primary focus of the present review was the person with frailty, but previous research has highlighted the needs of carers of people with frailty.15 Compared to relatives of people dying with cancer, the families of people with frailty are less satisfied with the professional support provided before death.30 This may point to deficiencies in the way that current services support relatives, as well as people with frailty.

Strengths and limitations

We undertook detailed searches across a broad range of research databases and grey literature sources, to produce a comprehensive review. A high proportion of the studies in the review are from North America, reflecting the origins and contemporary discussion in frailty care. However, our review also encompasses six European studies, which increases the international relevance of our findings. We chose to include only studies that explicitly defined frailty, so we can be sure that the needs identified are those of individuals who are frail, and not simply an ageing population. A wide range of definitions were employed, and Parkinson’s, dementia and multi-morbidity were commonly included (or not excluded) in the criteria used to define frailty. Thus, it is possible that some of the potential needs for palliative care identified in this review were associated specific diagnosed (or undiagnosed) medical conditions, other than frailty. We excluded qualitative literature during screening, some of which may have discussed evidence on care needs that have not been considered in our narrative synthesis. Frailty research has developed rapidly in recent years, so our focus on studies with a clear definition of frailty may also have excluded relevant work from earlier years. Most of the studies in this review were concerned with selected populations, recruited from general hospitals or intensive healthcare settings. This means that many of the people with frailty were at a critical phase in their care, and our findings may be less applicable to people earlier in the disease course, and those looked after by less specialised services.

What this study adds

Our findings have important implications for policy, practice and research. Our review suggests that people with frailty do have physical, psychosocial and support needs that are amenable to palliative intervention, but they are less likely to have these needs assessed. Primary care services are well positioned to assess and meet many of these physical needs directly and coordinate any specialist input. However, it seems that greater awareness of the end-of-life care needs of older adults with frailty may be required by health professionals, along with consideration of the role of specialist services. When people with frailty had been involved in discussions about future care, their recorded preferences for treatment were not always followed at the most critical phases of care. As palliative care pathways are developed for people with frailty, continuity and understanding of peoples’ preferences at all points during the final phases of life should be prioritised.

Many ways of measuring frailty or identifying people living with frailty are available to researchers, but to date, few have been consistently employed in palliative or end-of-life care studies (as demonstrated by the relatively small number of high-quality studies included in the present review). The majority of evidence is drawn from hospital settings where frailty is more likely to be assessed, but where people are at a critical phase in their care. Further primary research is needed to assess the needs of people with frailty earlier in the end-of-life trajectory. Increasing measurement of frailty in palliative and end-of-life care research will help to improve our understanding of the care needs of a growing population of people with frailty as they near end of life.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_A for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_B for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_C for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_D for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

DS undertook the searches, main analysis and interpretation and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. GS carried out the duplicate screening of records and contributed to the revision of the manuscript. FEM was involved in study design, contributed to the data interpretation and drafting the manuscript. BH conceived the study, oversaw the analysis and strategic direction, contributed to the data interpretation, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved it before submission.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the Medical Research Council (MC_U105292687 to F.E.M.). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

ORCID iD: Daniel Stow  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9534-4521

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9534-4521

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, et al. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(8): 1487–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population ageing. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013; 381(9868): 752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013; 14(6): 392–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56(3): M146–M156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007; 62(7): 722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, et al. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61(9): 1537–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drubbel I, De Wit NJ, Bleijenberg N, et al. Prediction of adverse health outcomes in older people using a frailty index based on routine primary care data. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013; 68(3): 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hope AA, Gong MN, Guerra C, et al. Frailty before critical illness and mortality for elderly medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(6): 1121–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pialoux T, Goyard J, Hermet R. When frailty should mean palliative care. J Nurs Educ Pract 2013; 3(7): 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maida V, Devlin M. Frailty, thy name is Palliative! Canadian Med Assoc J 2015; 187(17): 1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dixon J, King D, Matosevic T, et al. Equity in the provision of palliative care in the UK: review of evidence. London: Personal Social Services Research Unit, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2015, http://www.pssru.ac.uk/archive/pdf/4962.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14. Care quality Commission. A different ending: addressing inequalities in end of life care (People with conditions other than cancer). Newcastle upon Tyne: CQC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bone AE, Morgan M, Maddocks M, et al. Developing a model of short-term integrated palliative and supportive care for frail older people in community settings: perspectives of older people, carers and other key stakeholders. Age Ageing 2016; 45(6): 863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palliative end of life Priority Setting Partnership. Putting patients, carers and clinicians at the heart of palliative and end of life care research. London: Palliative and End of Life Care Priority Setting Partnership, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murtagh FE, Bausewein C, Verne J, et al. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliat Med 2014; 28(1): 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bennett MI, Davies EA, Higginson IJ. Delivering research in end-of-life care: problems, pitfalls and future priorities. Palliat Med 2010; 24(5): 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Treatment care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making. London: General Medical Council, 2010, p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Connor SR, Sepulveda Bermedo M. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. London: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups [Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed 1 October 2017).

- 22. Culyer AJ. Need: the idea won’t do – but we still need it. Soc Sci Med 1995; 40(6): 727–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centre for Reviews Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care (3rd edition). York: CRD, University of York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bradshaw JR. A taxonomy of social need. In: Cookson R, Sainsbury R, Glendinning C. (eds) Jonathan Bradshaw on Social Policy (Selected Writings 1972-2011). York: York Publishing Services Limited, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Institute for Health. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, 2014, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (accessed 1 October 2017).

- 26. Soto-Rubio A, Perez-Marin M, Barreto P. Frail elderly with and without cognitive impairment at the end of life: their emotional state and the wellbeing of their family caregivers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2017; 73: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amblas-Novellas J, Murray SA, Espaulella J, et al. Identifying patients with advanced chronic conditions for a progressive palliative care approach: a cross-sectional study of prognostic indicators related to end-of-life trajectories. BMJ Open 2016; 6(9): 12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chochinov HM, Johnston W, McClement SE, et al. Dignity and distress towards the end of life across four non-cancer populations. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(1): e0147607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heyland DK, Ilan R, Jiang XR, et al. The prevalence of medical error related to end-of-life communication in Canadian hospitals: results of a multicentre observational study. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25(9): 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hofstede JM, Raijmakers NJH, Van Der Hoek LS, et al. Differences in palliative care quality between patients with cancer, patients with organ failure and frail patients: a study based on measurements with the Consumer Quality Index Palliative Care for bereaved relatives. Palliat Med 2016; 30(8): 780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huijberts S, Buurman BM, De Rooij SE. End-of-life care during and after an acute hospitalization in older patients with cancer, end-stage organ failure, or frailty: a sub-analysis of a prospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2016; 30(1): 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, et al. Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(8): 1095–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heyland D, Cook D, Bagshaw SM, et al. The very elderly admitted to ICU: a quality finish. Crit Care Med 2015; 43(7): 1352–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lavergne M, Lethbridge L, Johnston G, et al. Examining palliative care program use and place of death in rural and urban contexts: a Canadian population-based study using linked data. Rural Remote Health 2015; 15(2): 3134–3146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT, McDermid RC, et al. Association between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among critically ill patients: a multicentre prospective cohort study. CMAJ 2014; 186(2): E95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ryan T, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, et al. Symptom burden, palliative care need and predictors of physical and psychological discomfort in two UK hospitals. BMC Palliat Care 2013; 12: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moorhouse P, Mallery LH. Palliative and therapeutic harmonization: a model for appropriate decision-making in frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(12): 2326–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ikegami N, Ikezaki S. Life sustaining treatment at end-of-life in Japan: Do the perspectives of the general public reflect those of the bereaved of patients who had died in hospitals. Health Policy 2010; 98(2–3): 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith AK, Cenzer IS, Knight SJ, et al. The epidemiology of pain during the last 2 years of life. Ann Intern Med 2010; 153(9): 563–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Munoz GS, Martin MBP. Frail elderly and palliative care. Psicothema 2008; 20(4): 571–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chibnall JT, Videen SD, Duckro PN, et al. Psychosocial–spiritual correlates of death distress in patients with life-threatening medical conditions. Palliat Med 2002; 16(4): 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pollack LR, Goldstein NE, Gonzalez WC, et al. The frailty phenotype and palliative care needs of older survivors of critical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(6): 1168–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, et al. The last 2 years of life: functional trajectories of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51(4): 492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. YashPal R, Kuan WS, Koh Y, et al. Death among elderly patients in the emergency department: A needs assessment for end-of-life care. Singapore Med J 2017; 58(3): 129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ernst KF, Hall DE, Schmid KK, et al. Surgical palliative care consultations over time in relationship to systemwide frailty screening. JAMA Surg 2014; 149(11): 1121–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thomas K. Prognostic Indicator Guidance (PIG) 4th Edition. The Gold Standards Framework Centre In End of Life Care CIC 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gómez-Batiste X, Martínez-Muñoz M, Blay C, et al. Recommendations for the comprehensive and integrated care of persons with Advanced chronic conditions and life-limited prognosis in Health and social services: NECPAL-CCOMS-ICO© 3.0 2016, http://ico.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/ico/professionals/documents/qualy/arxius/NECPAL-3.0-ENGLISH_full-version.pdf (accessed 1 October 2017)

- 48. Lynn J, Adamson D. Living well at the end of life: adapting health care to serious chronic illness in old age. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005; 173(5): 489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Botella J, Errando E, Martinez V. Los ancianos con enfer- medades en fase terminal. In: Imedio EL. (ed.) Enfermería En Cuidados Paliativos. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana S.A, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 2003; 289(18): 2387–2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983; 67(6): 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shega JW, Dale W, Andrew M, et al. Persistent pain and frailty: a case for homeostenosis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(1): 113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wade KF, Marshall A, Vanhoutte B, et al. Does pain predict frailty in older men and women? Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017; 72(3): 403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wilkie DJ, Ezenwa MO. Pain and symptom management in palliative care and at end of life. Nurs Outlook 2012; 60(6): 357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017; 15(1): 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Searle SD, Rockwood K. Frailty and the risk of cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther 2015; 7(1): 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Green E, Knight S, Gott M, et al. Patients’ and carers’ perspectives of palliative care in general practice: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2018; 32(4): 838–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mitchell GK, Senior HE, Johnson CL, et al. Systematic review of general practice end-of-life symptom control. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018; 8: 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Davidson S, Gentry T. End of life evidence review. London: SAGE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_A for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_B for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_C for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, 2018-05-14_-_Supplemental_D for What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Daniel Stow, Gemma Spiers, Fiona E Matthews and Barbara Hanratty in Palliative Medicine