Abstract

Background:

Melasma is a chronic hyperpigmentation skin disorder mainly affecting women in the reproductive age. Available treatments for melasma do not lead to long-term satisfactory results.

Aims:

This study aimed to compare the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser in combination with topical therapy to topical therapy alone.

Materials and Methods:

Forty women with bilateral melasma were studied in this randomized single-blinded clinical trial. Each side of the face was randomly allotted to either topical hydroquinone 4% or combination of topical hydroquinone 4% and fractional CO2 laser. Patients received three sessions of laser therapy at 3-week intervals. Hydroquinone 4% application on both sides maintained for 3 months after the last laser session. The clinical improvement (darkness [D] and homogeneity [H] of hyperpigmentation) was measured by a blinded main investigator and an outcome assessor. Furthermore, improvement was assessed by physician's global assessment (PGA) and patient satisfaction (visual analog scale [VAS] score).

Results:

Significant reduction in D observed 3 weeks after combination therapy (P<0.001) and 6 weeks after monotherapy (P<0.001). Reduction in H became significant after 6 weeks in both groups (P<0.001). However, the two methods were not considerably different in any session (P>0.05). Furthermore, control and experiment sides were not significantly different considering VAS score and PGA (P>0.05).

Conclusion:

Considering the short-term outcome of laser and hydroquinone therapy, we can apply it to obtain earlier positive results. However, because of the lack of significant difference between the two methods and also the high cost of laser therapy, it seems better not to recommend fractional CO2 laser to patients as adjunctive therapy for long-term treatment of melasma.

KEY WORDS: Fractional CO2 laser, hydroquinone, melasma

Introduction

Melasma is a chronic benign condition, characterized by skin hypermelanosis, which can develop in all types of skins. This disorder is usually seen in women of reproductive age.[1,2,3] The major clinical patterns of distribution are centrofacial, malar, and mandibular. In addition, melasma can be classified according to the depth of melanin pigment under the Wood's lamp into epidermal, dermal, and mixed.[1,3,4,5] Pathogenesis of melasma is not exactly known. Some of its risk factors include genetic, sunlight exposure, pregnancy, hormone replacement therapy, and photosensitizing drugs.[1,3,6]

The first-line treatment of melasma is topical agents such as hydroquinone, azelaic acid, kojic acid, and retinoic acid. The second-line includes chemical peels, which is mostly used in dark-skinned patients. Laser is the third-line therapy, which is mainly used in refractory or recurrent cases.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13] Hydroquinone 2%–4%, as the preferred treatment, administered in combination with retinoids and steroids is more effective than hydroquinone alone.[10,14,15,16] Triple topical therapy as the gold standard of treatment consists of hydroquinone, tretinoin, and corticosteroids (Kligman–Willis's formula);[17,18] but runs the risk of self-medication and steroid-induced side-effects. Since this formula is usually unsuccessful to produce long-term remission, different types of lasers have been tried.[19] Considering the therapeutic and adverse effects of laser are not completely understood, the use of laser monotherapy for melasma is not recommended.[20,21] Potential adverse effects of laser therapy include erythema, facial edema, burning sensation, and pain.[19,22] Some studies have been performed on the role of various types of lasers in facilitating transcutaneous drug delivery.[22,23,24] Complete ablation of the skin surface using laser would more effectively stub the stratum corneum and facilitates transcutaneous drug transport. Nevertheless, clinical applications of the method have been limited owing to its adverse effects.[19,20,22] Chen et al. showed that a safer ablative fractional laser could effectively facilitate transcutaneous delivery of drugs by generating microchannels in the skin.[24] Furthermore, some limited studies indicated that fractional CO2 laser resurfacing in combination with topical creams could be safe and effective for melasma treatment.[25,26]

With regard to the limitations of the previous studies and insufficient satisfaction of patients with current treatments, we designed this split-face clinical trial with more samples to compare the therapeutic effect of fractional CO2 laser plus topical hydroquinone 4% versus topical hydroquinone 4% monotherapy.

Materials and Methods

This single-blinded, prospective, parallel, randomized clinical trial approved by the institutional ethics committee (trial number: 391095) was performed from February 2015 to March 2016. The trial procedure design corresponded to the ethical basis laid down by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials under trial id number 30125. To detect the expected difference of 67% of standard deviation in darkness and homogeneity scores between the trial and control groups by considering power at 80%, significance level of 5%, it was required to study 35 patients with two-sided problem (70 cheeks). Five patients added to this number to compensate for dropout (14% of estimated sample size). Forty female patients (80 cheeks) attending a dermatology outpatient clinic, from the age range of 20–50 years with Fitzpatrick skin types II–V and with bilateral melasma were assigned in the study by the main investigator. Exclusion criteria included the history of receiving laser therapy and topical therapeutic agents in the previous 3 months, isotretinoin in the past 6 months, oral contraceptives (OCP), other bleaching creams, phenytoin, phototoxic and photoallergic drugs, pregnancy, and lactation. The participants should not have sun exposure a few days after laser therapy. Patients who had no desire to proceed with participation in the study, developing scars, keloid, or sensitivity to hydroquinone were excluded. After signing an informed consent in the first session, the patient's demographic data and medical history were obtained using a questionnaire. The lesion depth (epidermal, dermal, or mixed) was determined under the Wood's lamp examination.

For each patient, one cheek was considered as the control (hydroquinone group) and the other cheek as the experiment (laser and hydroquinone group) according to blocked randomization which was generated by a medical statistician. Participants were divided into Group A (right cheek as the experiment) and Group B (left cheek as the experiment) within the blocks of four each in equal proportions. Six different combinations of A and B could be possible for each block and only one of them allocated to each block using random numbers. Randomly generated treatment allocation sequence was concealed in the forty envelopes which were sequentially numbered and opened by the care provider only after each patient was assigned to the trial. Melasma and its margin on the side allocated to receive combination therapy was treated using fractional CO2 laser (Qray-FRX device, DOSIS M&M Co., Ltd.) by the care provider who was not blind to the type of treatment applied for each patient. Our chosen setting was laser fluence of 5 J/cm2, Dot cycle of 6, and Pixel pitch of 2. Laser therapy was done for three sessions at 3-week intervals. The patients were recommended to dress the laser therapy site by sterile vaseline gauze for 2 days, avoid applying any soap or cosmetic product and prevent direct sunlight exposure. Three days after the laser session, topical hydroquinone 4% was applied twice a day on both sides of the face except for around the eyes. Furthermore, in the morning, broad-spectrum sunscreens (SPF 50) was applied over it. In each session, potential adverse effects of laser and topical therapy were investigated. Each patient was followed up at 3-week intervals and 1 and 3 months after the last laser session.

At the beginning of each session before starting laser therapy, the blinded main investigator and the outcome assessor (consultant dermatologist) to the type of treatments applied in each side, assessed the severity of melasma lesions based on darkness (D) and homogeneity (H) using a 7-point scale (0–6).

We classified darkness and homogeneity as follows: 0 – normal skin or lack of the lesion, 1 – barely visible hyperpigmentation (D) or specks of involvement (H), 2 – mild hyperpigmentation or small patchy areas of involvement <1.5 cm in diameter, 3 – mild-to-moderate hyperpigmentation or patches of involvement 1.5–2 cm, 4 – moderate hyperpigmentation or patches of 2–2.5 cm, 5 – moderately severe hyperpigmentation or skin involvement >2.5 cm, and 6 – severe hyperpigmentation or uniform skin color.

Furthermore, response to treatment was evaluated subjectively by the main investigator and consultant dermatologist who were blinded to the treatment being given on each side. The grading of response was done by the percentage improvement in the lesions through the clinical photographs taken by the care provider in the first and last sessions as follows: No (0%), slight (≤25%), moderate (26%–50%), obvious (51%–75%), and marked (>75%) improvement (physician global assessment).[21,27,28] In addition, at the first and last visits, the patient's satisfaction with the treatment results was evaluated on visual analog scale (VAS) by scoring between 0 and 10.[29]

The outcome variables and parameters were tested for normal distribution using histogram and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The data obtained were analyzed by statistician of the institute using Chi-square test, paired t-test, and one-way ANOVA in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

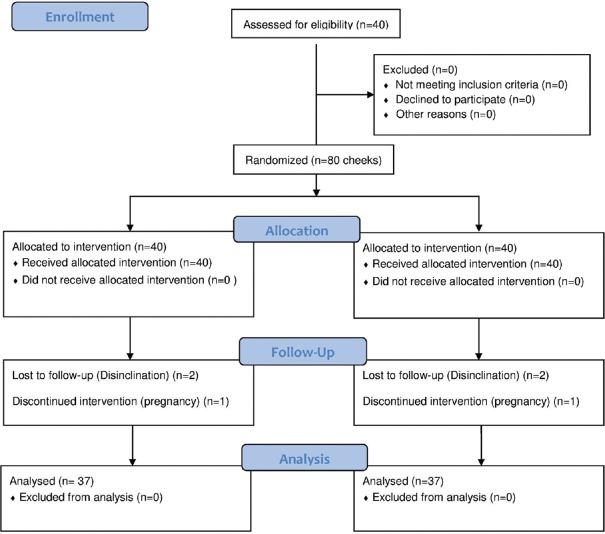

Among 40 patients enrolled, one patient became pregnant during the study and excluded from the study and two did not attend the follow-up visits [Figure 1]. Ultimately, 37 patients were studied (Attrition rate = 7.5%). Demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1. In the combination therapy side, 2 patients experienced erythema, 3 had burning, and in the hydroquinone side, 1 patient experienced burning. However, none of them left the study due to adverse effects.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of studied population

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of patients with melasma (n=37)

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 36.9±5.5 |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 31 (83.8) |

| Single | 6 (16.2) |

| Mean age at onset of melasma (years) | 30.2±5.4 |

| Mean duration of melasma (years) | 6.7±4.2 (1 month-20 years) |

| Positive family history of melasma, n (%) | 22 (59.5) |

| Previous treatments for melasma, n (%) | |

| Laser therapy | 2 (5.4) |

| Hydroquinone | 12 (32.4) |

| Combination of laser and hydroquinone | 4 (10.8) |

| Skin types, n (%) | |

| Type II | 6 (16.2) |

| Type III | 22 (59.5) |

| Type IV | 6 (16.2) |

| Type V | 3 (8.1) |

| Predisposing factors for melasma, n (%) | |

| Oral contraceptives | 6 (16.2) |

| Postpartum | 14 (37.8) |

| Underlying medical conditions (hypothyroidism, ovarian cyst and hepatic disorders) | 9 (24.3) |

The mean darkness scores obtained on the three laser and follow-up sessions are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Change in mean and standard deviation of darkness score on the experiment and control sides

| Group | Darkness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 week | 3 weeks | 6 weeks | 10 weeks (follow-up) | 18 weeks (follow-up) | P | |

| Laser + hydroquinone | 3.8±0.82 95% CI (3.52-4.07) |

2.8±1.00 95% CI (2.46-3.13) |

2.4±0.94 95% CI (2.08-2.71) |

2.1±0.96 95% CI (1.78-2.42) |

2±1.70 95% CI (1.43-2.57) |

<0.001 |

| Hydroquinone | 3.6±0.95 95% CI (3.28-3.91) |

3.2±0.95 95% CI (2.88-3.51) |

2.3±0.99 95% CI (1.97-2.63) |

2.3±0.99 95% CI (1.97-2.63) |

1.98±1.00 95% CI (1.64-2.31) |

<0.001 |

| P | 0.335 | 0.082 | 0.657 | 0.380 | 0.524 | - |

CI: Confidence interval

According to one-way ANOVA model, reduction in darkness score was significant after 3 weeks in the combination therapy group (P<0.001) and after 6 weeks in the monotherapy group (P<0.001). Furthermore, a statistically significant decrease for both groups was observed in the follow-up sessions compared with the scores obtained on the 1st day. However, according to paired t-test, the efficacy of the two treatments was not significantly different.

Table 3 provides the average of homogeneity changes of the skin lesions for the two sides before treatment and in the follow-up sessions.

Table 3.

Change in the mean and standard deviation of homogeneity score on the experiment and control sides

| Group | Homogeneity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 week | 3 weeks | 6 weeks | 10 weeks (follow-up) | 18 weeks (follow-up) | P | |

| Laser + hydroquinone | 3.7±0.79 95% CI (3.43-3.96) |

3.4±0.72 95% CI (3.16-3.64) |

2.7±0.94 95% CI (2.38-3.01) |

2.4±1.10 95% CI (2.03-2.76) |

2.2±0.99 95% CI (1.87-2.53) |

<0.001 |

| Hydroquinone | 3.6±0.87 95% CI (3.31-3.89) |

3.4±0.92 95% CI (3.09-3.70) |

2.9±0.83 95% CI (2.62-3.17) |

2.6±0.97 95% CI (2.27-2.92) |

2±0.99 95% CI (1.67-2.33) |

<0.001 |

| P | 0.606 | 1.000 | 0.335 | 0.409 | 0.387 | - |

CI: Confidence interval

According to the results obtained by one-way ANOVA, a significant reduction in homogeneity score was observed at the end of the 6th week with combination therapy (P<0.001) and monotherapy (P=0.0007). Although a statistically significant decrease for both sides was observed at the end of the study, according to the paired t-test, two methods were not considerably different in any session (P>0.05).

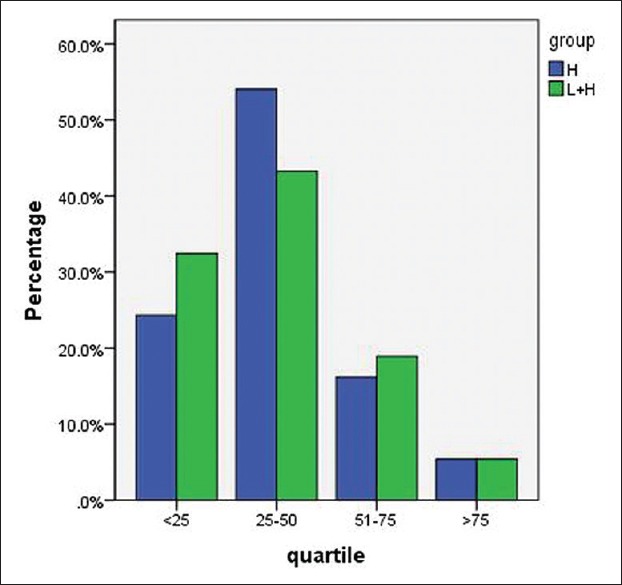

Percentage improvement evaluated by a nontreating physician on the experiment and control sides in the last follow-up session is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Physician visual analog scale on the experiment and control sides. (H: Hydroquinone, H + L: Hydroquinone + Laser)

According to the results obtained by the Chi-square test, the two methods were not significantly different in this respect (P=0.813).

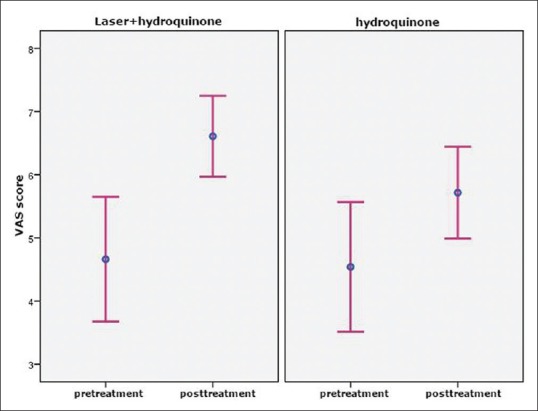

The Spatients’ satisfaction was investigated before the experiment and in the last follow-up session with VAS score. On the side treated by the combination of laser and hydroquinone, satisfaction with the treatment increased from 4.66±3 to 6.6±2, which showed a statistically significant change (P=0.002). On the other hand, on the side treated with hydroquinone, the value increased from 4.44±3 to 5.7±2, which was a statistically significant change (P=0.005). The changes in the patients’ VAS scores for the two treatments are provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Changes in the visual analog scale scores before and after the treatments (95% confidence interval plot)

The mean increase in the patients’ satisfaction score in a 10-point scale was 1.94 and 1.26 in the combination therapy and monotherapy, respectively. The two treatments were not significantly different in this respect (P>0.05).

Discussion and Conclusion

Melasma, a hyperpigmentary condition with idiopathic etiology, is resistant to therapy. We tried to evaluate the effect of fractional CO2 laser over and above the effect of hydroquinone in melasma.

According to the results obtained, the mean age of patients was 36.9±5.5 and 59.5% of patients had positive family history. These results are in accordance with findings from other studies.[1,27,30] Oral contraceptive pill was associted with melasma in 16.2% patients and 37.8% experienced the problem postpartum. These findings are in correlation with other reported studies.[27,29,30] In our study, the significant reduction in darkness score was seen after 3 weeks in the combination therapy group and after 6 weeks in the monotherapy group. Although at the beginning of the study, the mean darkness score in the group receiving combination therapy was slightly higher than the other group, the decrease in the darkness was clinically higher in this group. In other words, combination therapy led to a better response in short term. On the other hand, a statistically significant reduction in homogeneity score was reported after 6 weeks in both the groups. The pattern of homogeneity change was not as obvious as that observed for the skin darkness. However, considering the long-term effect of the treatments, 3 months after the last laser therapy session, despite significant reduction in the lesional darkness and homogeneity in each group, two methods were not significantly different. Regarding PGA and patients’ VAS, although two groups were not significantly different, the patients had overall higher satisfaction with the results of combination therapy. This could be interpreted by the fact that patients were possibly more influenced by placebo effect of the novel treatments and tended to express higher satisfaction proportional to the cost.

Various lasers have shown to make improvement in melasma treatment.[31,32,33] In the studies that compared laser versus topical therapy, laser monotherapy did not show greater benefits.[20,21,22] Application of topical therapy in combination with laser has led to varying results. In one study, yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) laser with or without chemical peeling has shown no significant difference in reduction of MASI score in long-term follow-up which is in accordance with our findings.[28] In the current study, although we observed remarkable improvement in darkness reduction during the first 3 weeks after combination therapy, its long-term improvement was limited. At the end of the treatment, we observed >75% improvement in only 5.4% of the patients and 75.67% of the patients had <50% improvement with combination therapy. This is consistent with the results reported by Tourlaki et al.[34]

Out of reported studies, there are few randomized controlled trials which evaluate topical monotherapy versus combination of laser and topical treatment. Wang et al. assessed the efficacy of intense pulsed light (IPL) and hydroquinone 4% treatment versus hydroquinone alone in patients with refractory melasma. Patients in the IPL group had significantly greater improvement relative to the control group. However, IPL usage is limited due to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and recurrence.[35] In another study, Q-switched-neodymium-doped: YAG in combination with hydroquinone 2% in comparison to hydroquinone alone produced only temporary improvement and the outcome was transient along with complications and high chance of recurrence.[36] These results were not compatible with ours, which could be due to different type of laser, bigger sample size, and split-face randomization in our method. Furthermore, after 3-months follow-up, we did not observe recurrence and PIH. Another study by Trelles et al. showed that a combination of fractional CO2 laser and Kligman's formula produced statistically significant improvement compared to monotherapy group.[26] The difference in results between this study and ours might be due to smaller sample size (10 patients in each group) and different method of randomization in Trelles study. In our survey, 2 groups of 37 cheeks were selected on the basis of split-face randomization to control probable selection bias such as age, genetic characteristics, environmental factors.

It can be concluded that, despite the increase in sample size and split-face randomization, the two methods were not statistically significant in short-term follow-up with regard to clinical response to treatment, patients’ satisfaction, and physician global assessment. Thus, considering the obtained results and the high cost of laser therapy, this approach is not cost-effective. Available topical treatments remain the gold standard for melasma treatment since they are cheap and show similar effectiveness compared to combination therapy.

Limitation of the study

Application of hydroquinone at high doses in summer is difficult and may cause photosensitivity. Since laser therapy sessions were limited, it is suggested to carry out studies with a higher number of sessions and also alteration of the treatment parameters to enhance the penetration depth of the laser. Moreover, to investigate the recurrence of the disorder, it is recommended to carry out long-term follow-ups.

Financial support and sponsorship

The Isfahan University of Medical Sciences financially supported this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Handel AC, Miot LD, Miot HA. Melasma: A clinical and epidemiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:771–82. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheth VM, Pandya AG. Melasma: A comprehensive update: Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:689–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkar R, Arora P, Garg VK, Sonthalia S, Gokhale N. Melasma update. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:426–35. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.142484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandyopadhyay D. Topical treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:303–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.57602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandry Pagán R, Sánchez JL. Mandibular melasma. P R Health Sci J. 2000;19:231–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynde CB, Kraft JN, Lynde CW. Topical treatments for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Skin Therapy Lett. 2006;11:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheth VM, Pandya AG. Melasma: A comprehensive update: Part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:699–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rendon M, Berneburg M, Arellano I, Picardo M. Treatment of melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:S272–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, Prota G. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073:85–90. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90186-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivas S, Pandya AG. Treatment of melasma with topical agents, peels and lasers: An evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:359–76. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar R, Chugh S, Garg VK. Newer and upcoming therapies for melasma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:417–28. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.98071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkar R, Garg V, Bansal S, Sethi S, Gupta C. Comparative evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of glycolic acid, salicylic mandelic acid, and phytic acid combination peels in melasma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:384–91. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibrahim ZA, Gheida SF, El Maghraby GM, Farag ZE. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of combinations of hydroquinone, glycolic acid, and hyaluronic acid in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:113–23. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sehgal VN, Verma P, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, Verma S. Melasma: Treatment strategy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2011;13:265–79. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2011.630088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salem A, Gamil H, Ramadan A, Harras M, Amer A. Melasma: Treatment evaluation. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11:146–50. doi: 10.1080/14764170902842549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar R, Arora P, Garg KV. Cosmeceuticals for hyperpigmentation: What is available? J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:4–11. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.110089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kligman AM, Willis I. A new formula for depigmenting human skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shankar K, Godse K, Aurangabadkar S, Lahiri K, Mysore V, Ganjoo A, et al. Evidence-based treatment for melasma: Expert opinion and a review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2014;4:165–86. doi: 10.1007/s13555-014-0064-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora P, Sarkar R, Garg VK, Arya L. Lasers for treatment of melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5:93–103. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.99436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halachmi S, Haedersdal M, Lapidoth M. Melasma and laser treatment: An evidenced-based analysis. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29:589–98. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wind BS, Kroon MW, Meesters AA, Beek JF, van der Veen JP, Nieuweboer-Krobotová L, et al. Non-ablative 1,550 nm fractional laser therapy versus triple topical therapy for the treatment of melasma: A randomized controlled split-face study. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:607–12. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sofen B, Prado G, Emer J. Melasma and post inflammatory hyperpigmentation: Management update and expert opinion. Skin Therapy Lett. 2016;21:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, McAuliffe DJ, Flotte TJ, Kollias N, Doukas AG. Photomechanical transcutaneous delivery of macromolecules. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:925–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Shah D, Kositratna G, Manstein D, Anderson RR, Wu MX, et al. Facilitation of transcutaneous drug delivery and vaccine immunization by a safe laser technology. J Control Release. 2012;159:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neeley MR, Pearce FB, Collawn SS. Successful treatment of malar dermal melasma with a fractional ablative CO2 laser in a patient with type V skin. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:258–60. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2010.538412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trelles MA, Velez M, Gold MH. The treatment of melasma with topical creams alone, CO2 fractional ablative resurfacing alone, or a combination of the two: A comparative study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:315–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sardesai VR, Kolte JN, Srinivas BN. A clinical study of melasma and a comparison of the therapeutic effect of certain currently available topical modalities for its treatment. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:239. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.110842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DB, Suh HS, Choi YS. A comparative study of low-fluence 1,064 nm Q-Switched Nd:YAG laser with or without chemical peeling using Jessner's solution in melasma patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:523–8. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.848261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh R, Goyal S, Ahmed QR, Gupta N, Singh S. Effect of 82% lactic acid in treatment of melasma. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:407142. doi: 10.1155/2014/407142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: A clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Na SY, Cho S, Lee JH. Intense pulsed light and low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment in melasma patients. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:267–73. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kauvar AN. Successful treatment of melasma using a combination of microdermabrasion and Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:117–24. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz TM, Glaich AS, Goldberg LH, Firoz BF, Dai T, Friedman PM, et al. Treatment of melasma using fractional photothermolysis: A report of eight cases with long-term follow-up. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1273–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tourlaki A, Galimberti MG, Pellacani G, Bencini PL. Combination of fractional erbium-glass laser and topical therapy in melasma resistant to triple-combination cream. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:218–22. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2012.671911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang CC, Hui CY, Sue YM, Wong WR, Hong HS. Intense pulsed light for the treatment of refractory melasma in Asian persons. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1196–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wattanakrai P, Mornchan R, Eimpunth S. Low-fluence Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (1,064 nm) laser for the treatment of facial melasma in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]