Abstract

This study compares scores on 5 validated symptom questionnaires with results of clinical testing to assess the diagnostic accuracy of each questionnaire in identifying patients with dry eye disease.

Dry eye disease is a complex heterogeneous and multifactorial condition.1 Validated questionnaires are frequently used to screen for dry eye symptoms before assessing tear film homeostasis markers.1 Recently, the international Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop II (TFOS DEWS II) recommended the use of the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) and 5-item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5) as part of the dry eye diagnostic criteria.1 This prospective, investigator-masked, diagnostic accuracy study sought to compare the discriminative ability of the OSDI, DEQ-5, McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire, Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye (SANDE), and Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) questionnaires in detecting objective signs of dry eye disease.

Methods

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki2 and was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee, and participants provided written informed consent. Participants were required to be 18 years or older and to have undergone no surgical procedures within 3 months of study participation. In all, 211 participants were recruited through a population-based open recruitment strategy, satisfying diagnostic accuracy power calculations (sample size ≥153; estimated prevalence, 50%; anticipated sensitivity, 70%; 2-sided significance, α = .05; and power, 80%).

Brief standardized instructions were provided before administering the OSDI, DEQ-5, McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire, SANDE, and SPEED questionnaires in a randomized order. An independent observer then evaluated right-eye ocular surface parameters using a keratograph (OCULUS Keratograph 5M; OCULUS Inc) and measured the tear film osmolarity of both eyes (TearLab Osmometer; TearLab Corporation).3 The presence of clinical signs of dry eye disease was assessed according to the homeostasis markers arm of the TFOS DEWS II dry eye diagnostic criteria: noninvasive tear film breakup time less than 10 seconds; tear film osmolarity 308 mOsm/L or greater; interocular difference in osmolarity greater than 8 mOsm/L; more than 5 corneal staining spots; more than 9 conjunctival staining spots; or eyelid margin staining 2 mm or greater in length and 25% or greater in width.1

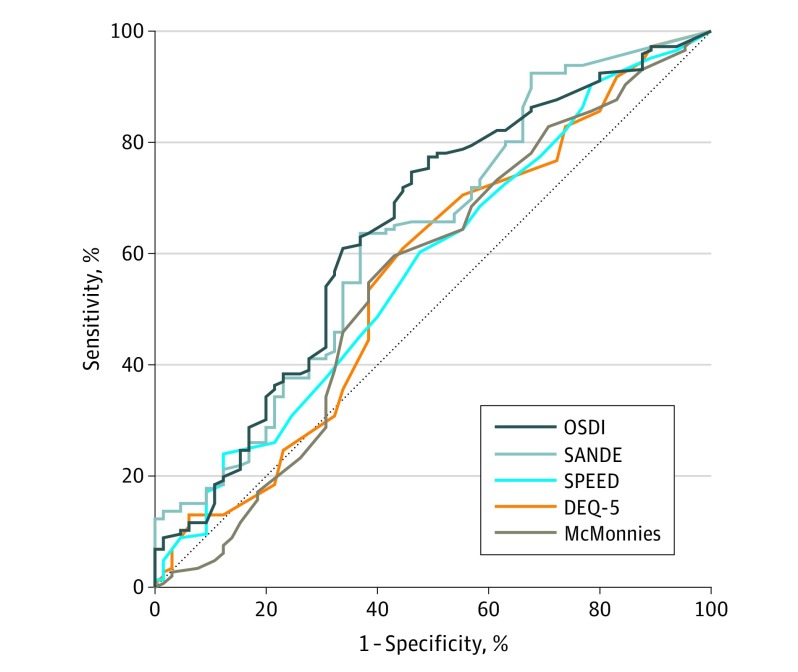

Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed to compare the discriminative ability of the questionnaires in detecting objective signs of dry eye disease. The area under the curve (C statistic) and Youden optimal diagnostic cutoff sensitivity and specificity were calculated. A Bonferroni-corrected, 2-sided significance threshold of P < .01 was used.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the 211 participants was 41 (18) years. One hundred twenty-four (58.8%) were female; 128 (60.7%) were of European, 54 (25.6%) of East Asian, 24 (11.4%) of South Asian, and 5 (2.4%) of other race/ethnicity. Overall, 146 (69.2%) participants fulfilled the TFOS DEWS II criteria for dry eye signs. The median (IQR) noninvasive tear film breakup time was 8.6 (5.2-12.4) seconds, the mean (SD) tear osmolarity was 310 (12) mOsm/L, and the mean (SD) interocular difference in osmolarity was 8 (6) mOsm/L. Seventy-one (33.6%) participants exhibited more than 5 corneal spots, 107 (50.7%) participants exhibited more than 9 conjunctival spots, and 97 (46.0%) participants exhibited eyelid margin staining 2 mm or greater in length and 25% or greater in width.

The diagnostic accuracy values of the 5 questionnaires are presented in the Table, and receiver operating characteristic curves are illustrated in the Figure. The discriminative abilities of the OSDI (C statistic, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.56-0.73; P < .001) and SANDE (C statistic, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.55-0.72; P = .002) scores were significantly greater than chance, but discriminative abilities of the SPEED (C statistic, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.49-0.66; P = .09), DEQ-5 (C statistic, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.47-0.65; P = .14), and McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire (C statistic, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.46-0.64; P = .20) scores were not.

Table. Diagnostic Accuracy Values of 5 Dry Eye Questionnaires Among 211 Participants .

| Questionnaire | Median (IQR) Score | C Statistic (95% CI) | P Value | Youden Optimal Diagnostic Cutoff | % (95% CI) | Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive | Negative | |||||

| OSDI score | 25 (12-40) | 0.65 (0.56-0.73) | <.001 | >14 | 78 (67-88) | 50 (42-58) | 1.57 (1.28-1.93) | 0.43 (0.26-0.70) |

| DEQ-5 score | 8 (6-12) | 0.56 (0.47-0.65) | .14 | >7 | 60 (47-72) | 55 (46-63) | 1.33 (1.02-1.73) | 0.73 (0.52-1.02) |

| McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire score | 16 (9-21) | 0.55 (0.46-0.64) | .20 | >14 | 57 (44-69) | 60 (52-68) | 1.43 (1.07-1.92) | 0.71 (0.52-0.97) |

| SANDE score | 4.2 (1.8-6.6) | 0.63 (0.55-0.72) | .002 | >4 | 65 (52-76) | 63 (55-71) | 1.75 (1.32-2.31) | 0.56 (0.40-0.80) |

| SPEED score | 12 (6-17) | 0.58 (0.49-0.66) | .09 | >10 | 60 (47-72) | 52 (44-60) | 1.25 (0.96-1.62) | 0.77 (0.55-1.08) |

Abbreviations: DEQ-5, 5-item Dry Eye Questionnaire; IQR, interquartile range; OSDI, Ocular Surface Disease Index; SANDE, Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye; SPEED, Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness.

Figure. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves of the 5 Validated Dry Eye Symptom Questionnaires.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of the discriminative ability of the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5), McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire (McMonnies), Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye (SANDE), and Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) questionnaires in detecting objective signs of dry eye disease. The dotted line represents the diagonal line of no discrimination or random chance. The magnitude of the area under the curve indicates the discriminative ability of each individual symptom questionnaire in detecting clinical signs of dry eye disease.

Discussion

The TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology Report highlighted the considerable heterogeneity in the study populations, methodologies, and reference standards used in previous diagnostic accuracy studies of validated dry eye symptom questionnaires.1 This heterogeneity can introduce significant challenges when interpreting the relative performance of these screening instruments. To our knowledge, this is the first study that offers a direct comparison of the 5 questionnaires within the same study population by using the TFOS DEWS II diagnostic criteria for clinical signs of dry eye disease as the reference standard.

This study is not without limitations. The recruited participants were predominantly of European, East Asian, and South Asian ethnicity, and eligibility required participants to have had no surgical procedures 3 months before study participation. These limitations may potentially affect the applicability of study findings to other ethnic groups and to persons with the iatrogenic postoperative dry eye conditions excluded from the study.

The results showed that the OSDI and SANDE scores had superior discriminative ability in detecting dry eye signs compared with the SPEED, DEQ-5, and McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire scores. The optimal diagnostic cutoff values of the symptom scores were similar to those reported previously.1,4,5 However, the C statistic, sensitivity, and specificity values of the 5 questionnaires were all relatively modest and potentially reflect the heterogeneous nature and complex interrelationships between ocular surface homeostatic disturbances, somatosensory pathways, and symptomatic experiences of dry eye disease.6,7

References

- 1.Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):539-574. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung J, Wang MTM, Lee SH, et al. Randomized double-masked trial of eyelid cleansing treatments for blepharitis. Ocul Surf. 2018;16(1):77-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DR, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):94-101. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Caffery B. Validation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5). Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33(2):55-60. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galor A, Levitt RC, McManus KT, et al. Assessment of somatosensory function in patients with idiopathic dry eye symptoms. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(11):1290-1298. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.3642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang MTM, Craig JP. Comparative evaluation of clinical methods of tear film stability assessment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(3):291-294. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.6489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]