Abstract

This cross-sectional study of data from the National Health Interview Survey analyzes the prevalence of e-cigarette use in US patients with cancer.

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have become increasingly popular in the United States1 and are advertised as a potentially safe and useful method of smoking cessation, despite unknown long-term health sequelae.2,3 Individuals with cancer are particularly sensitive to the harms of active smoking, thus smoking cessation is a critical component of cancer survivorship.4 However, the patterns and implications of e-cigarette use in patients with cancer are not well known. Therefore, we examined contemporary trends of conventional smoking and e-cigarette use among patients with cancer.

Methods

The National Health Interview Survey, an annual cross-sectional survey, collects data on a range of health indicators for noninstitutionalized, civilian adults.5 Beginning in 2014, participants were queried about e-cigarette use. Harmonized data of participants reporting a cancer diagnosis were obtained through the Integrated Health Interview Series.6

Data analysis was conducted from 2014 to 2017. Multivariable logistic regression defined the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and associated 95% CIs for the odds of using e-cigarettes, with year of survey response (2014-2015 vs 2016-2017) as the primary independent variable, including an age (<50 vs ≥50 years) × year of survey (2014-2015 vs 2016-2017) interaction term. Predicted margins defined prevalence standardized to the distribution of the covariates. Sample weighting stratified by year defined nationally representative estimates. The institutional review board at the University of Texas Southwestern deemed the study exempt, and patient written consent was waived.

Results

Among 13 274 participants (median [range] age, 68 [18-85] years) reporting a cancer diagnosis, 1259 (9.5%) had used e-cigarettes. Although the rates of conventional smoking remained stable from 2014 to 2017 (50.7% to 51.9%, P = .36), the prevalence of e-cigarette use increased from 8.5% to 10.7% (P = .01) (Figure, A), and later survey year (2016-2017) was associated with increased odds of e-cigarette use (AOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.01-1.57).

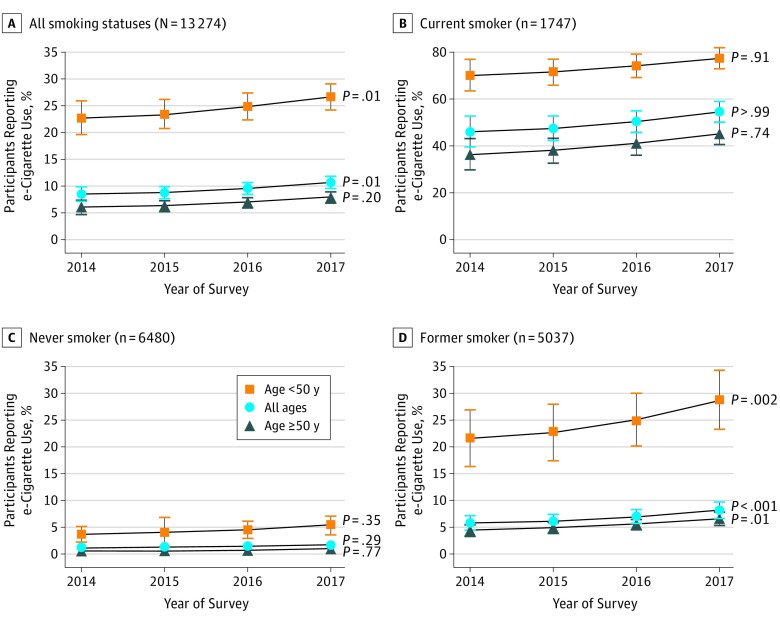

Figure. Prevalence of e-Cigarette Use Stratified by Smoking Status.

e-Cigarette use among all participants (A) reporting a diagnosis of cancer by year of survey, current smokers (B), never smokers (C), and former smokers (D). The error bars indicate 95% CIs. There were 10 patients with unknown smoking status.

Age younger than 50 years was also associated with higher odds of e-cigarette use (AOR, 3.79; 95% CI, 2.86-5.03), and the positive association between later survey year (2016-2017) and e-cigarette use was seen only in participants younger than 50 years (AOR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.17-2.51) and not in those 50 years or older (AOR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.82-1.35) (P = .02 for age × year interaction). From 2014 to 2017, the prevalence of e-cigarette use among participants younger than 50 years increased from 22.8% to 26.8% (P = .01), compared with 6.0% to 8.0% (P = .20) for those 50 years or older (Figure, A).

Although the prevalence of e-cigarette use among current and never smokers remained stable throughout the study period (Figure, B and C), e-cigarette use among former smokers increased from 5.8% to 8.3% between 2014 and 2017 (P < .001) (Figure, D).

Discussion

In this large contemporary national survey, the prevalence of e-cigarette use among participants reporting a cancer diagnosis increased from 2014 to 2017, whereas conventional smoking rates remained stable. The high prevalence of e-cigarette use among current conventional smokers calls into question whether e-cigarettes are a useful method of smoking cessation, although prospective studies are needed to address this concern. Notably, the trend for increasing e-cigarette use in our study appeared to be driven by former smokers and participants younger than 50 years. The health outcomes of former smokers who use e-cigarettes merits further study to elucidate the long-term health effects of switching to e-cigarettes. Among the general population, experts worry that e-cigarettes may be creating addiction to nicotine among younger individuals who are at risk of prolonged exposure.3 Our findings prompt similar concerns regarding potential deleterious long-term consequences on oncologic outcomes and survivorship, including the potential for increased cancer risk, for which further investigation is needed.

There are several important limitations to our work: data were self-reported, most of the participants in our cohort were white, and we cannot comment on whether e-cigarette use affected quantity of conventional smoking. Given the unknown consequences of e-cigarette use in those with cancer, policy and guidelines are needed, including e-cigarette screening and cessation as a part of cancer survivorship counseling.

References

- 1.Bao W, Xu G, Lu J, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB. Changes in electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(19):2039-2041. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.4658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, Stead LF, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD010216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. http://www.nationalacademies.org/eCigHealthEffects. Accessed November 16, 2018.

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Smoking cessation (version 1.2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/smoking.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2018.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National health interview survey: methods. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/methods.htm. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- 6.Blewett LA, Rivera Drew JA, Griffin R, King ML, Williams KCW IPUMS health surveys: national health interview survey, Version 6.3. [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. https://nhis.ipums.org/nhis/. doi: 10.18128/D070.V6.3. [DOI]