Abstract

Purpose

We determine if monomethyl fumarate (MMF) can protect the retina in mice subjected to light-induced retinopathy (LIR).

Methods

Albino BALB/c mice were intraperitoneally injected with 50 to 100 mg/kg MMF before or after exposure to bright white light (10,000 lux) for 1 hour. Seven days after light exposure, retinal structure and function were evaluated by optical coherence tomography (OCT) and electroretinography (ERG), respectively. Retinal histology also was performed to evaluate photoreceptor loss. Expression levels of Hcar2 and markers of microglia activation were measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the neural retina with and without microglia depletion. At 24 hours after light exposure, retinal sections and whole mount retinas were stained with Iba1 to evaluate microglia status. The effect of MMF on the nuclear factor kB subunit 1 (NF-kB) and Nrf2 pathways was measured by qPCR and Western blot.

Results

MMF administered before light exposure mediated dose-dependent neuroprotection in a mouse model of LIR. A single dose of 100 mg/kg MMF fully protected retinal structure and function without side effects. Expression of the Hcar2 receptor and the microglia marker Cd14 were upregulated by LIR, but suppressed by MMF. Depleting microglia reduced Hcar2 expression and its upregulation by LIR. Microglial activation, upregulation of proinflammatory genes (Nlrp3, Caspase1, Il-1β, Tnf-α), and upregulation of antioxidative stress genes (Hmox1) associated with LIR were mitigated by MMF treatment.

Conclusions

MMF can completely protect the retina from LIR in BALB/c mice. Expression of Hcar2, the receptor of MMF, is microglia-dependent in the neural retina. MMF-mediated neuroprotection was associated with attenuation of microglia activation, inflammation and oxidative stress in the retina.

Keywords: retinal degeneration, neuroprotection, monomethyl fumarate, light-induced retinopathy

Photoreceptor degeneration is a common hallmark in several retinal degenerative diseases causing blindness, such as dry age-related macular degeneration (dry AMD)1 and inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs).2 Currently, no treatment is approved for dry AMD. For IRDs, the recently approved gene therapy voretigene neparvovec targets only one3 of over 250 genes known to cause IRDs (RetNet, available in the public domain at https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/). Developing gene therapies for the remaining IRDs faces several challenges: some genes are too large to fit into current gene therapy vectors, some causative genes are unknown, and each gene therapy must be approved individually by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). To treat the vast array of patients with photoreceptor degeneration, alternative approaches are needed. An attractive mutation-independent approach is the application of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) modulators to protect from photoreceptor degeneration.4–11 These treatments could be used independently, or in conjunction with gene therapies to slow retinal degeneration. Importantly, the use of FDA-approved GPCR modulators will greatly facilitate translation of the therapy for dry AMD and IRDs.

Dimethyl fumarate (DMF), marketed as Tecfidera, is a FDA-approved oral drug for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS).12 After oral administration, DMF is quickly hydrolyzed to its active metabolite monomethyl fumarate (MMF).13 MMF is an agonist of the hydroxyl-carboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCAR2), a Gαi-protein coupled receptor (GαiPCR) that is highly expressed on macrophages and adipocytes, with β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) as the physiological ligand.14 HCAR2 signaling in macrophages and microglia cells reduces inflammation by inhibiting the activation of nuclear factor kB subunit 1 (NF-kB)15,16 and the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome.17,18 DMF confers neuroprotection through HCAR2-dependent anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory mechanisms.19,20 Additionally, DMF/MMF activates nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 2 (NRF2),21,22 a master transcription factor regulating multiple endogenous antioxidants,23 by direct covalent modification at the 151C residue of KEAP1 (the suppressor of NRF2), resulting in NRF2 activation and reduced oxidative stress in vivo and in vitro.24

Previous studies of MMF in the retina have demonstrated promotion of retinal vascular integrity and RPE barrier function in a humanized mouse model of sickle cell disease25 and protection of retinal ganglion cells from retinal ischemia-reperfusion.22 Furthermore, oxidative stress due to impaired NRF2 signaling,26,27 activation of microglia,28,29 and chronic inflammation mediated by NF-kB30,31 and the NLRP3 inflammasome32,33 are reported to be mechanistically linked to dry AMD and IRDs. Given the ability of MMF to target multiple neuroprotective pathways and its efficacy in other models of retinal disease, we hypothesized that MMF would prevent photoreceptor degeneration, a hallmark of IRDs and dry AMD. MMF targets these pathways directly and its pro-drug is FDA-approved, making it an attractive target for therapeutic development. Thus, we investigated the efficacy and molecular mechanisms of MMF in mouse model of light-induced retinopathy (LIR).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Albino BALB/c mice (male, 6 weeks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were housed in a 12-hour alternate light/dark cycling room (15 lux during the light phase) for at least 2 weeks before experiments. All experimental procedures followed the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon Health and Science University and adhered to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Mouse Model of LIR

Our mouse model of LIR was described previously.4,5 BALB/c mice were dark adapted for 2 hours at the end of a 12-hour light cycle before exposure to bright white light (∼10,000 lux of uniform light) for 1 hour to produce LIR. After light exposure, mice were maintained in the alternate light/dark cycling room until data acquisition.

Drug Preparation and Injections

MMF (Product No. 651419; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in PBS at room temperature. For intraperitoneal injections under dim red light, a single dose (50, 65, 75, 100 mg/kg) of MMF or PBS was delivered into mice immediately before bright light exposure, or a single 100 mg/kg of MMF was delivered to mice at 1 hour after light exposure. For intravitreal injections, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Eyes were dilated with 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine. One μL of MMF (1 or 5 μg) or PBS was delivered transscleral with a 33-gauge beveled needle. Naive mice were not injected or exposed to bright light.

Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) and Image Segmentation

Seven days after bright light exposure, mouse retinas were imaged using SD-OCT as described previously.4,5 All four retinal quadrants (temporal, nasal, superior, and inferior) were imaged. Retinal layers were segmented using a custom-designed SD-OCT segmentation program built in IGOR Pro (IGOR Pro 6.37; WaveMetrics, Inc., Lake Oswego, OR, USA). The receptor layer (REC+) was defined as the thickness from Bruch's membrane to the interface of the inner nuclear layer (INL) and outer plexiform layer (OPL).

Electroretinography (ERG)

ERG was performed at 8 to 10 days after light exposure as described previously.4,5 Before ERG, mice were dark-adapted overnight. Under dim red light, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Bilateral platinum electrodes were placed on the corneal surface to record the light-induced retinal potentials, with the reference and ground electrode placed subcutaneously in the forehead and tail, respectively. ERG responses were recorded at increasing light intensities from −4.34 to 3.55 log cd s/m2.

Immunohistochemistry

At specified time points (see Figure legends), mouse eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 2 hours. For whole mount retinas, the neural retina was dissected from posterior eye cups and washed with PBS for 10 minutes before blocking/permeabilizing (0.3% Triton X-100 + 2% BSA + 2.5% donkey serum in PBS) overnight at 4°C. For transverse retinal sections, posterior eyecups were dissected and incubated in 30% sucrose solution for 2 hours at room temperature before embedding in OCT media and sectioning. Retinal cryosections (50 μm) were washed with PBS, and also blocked/permeabilized (0.3% Triton X-100 + 2% BSA + 2.5% donkey serum in PBS) for 2 hours at 4°C. All retinal tissues were incubated with anti-Iba1 antibody (1:500, Cat# 019-19741; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA, USA) overnight at 4°C, washed with PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody (donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 647, 1:800, Cat# A31573; Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA). All stained retinal tissues were imaged with a white light laser confocal microscope (TCS SP8 X; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). For whole mount retina, Z-stacks (spanned 90 um with 3 um interval) were collected using a ×10 objective, and maximum intensity projections were made for further analysis. For retinal cross-sections, Z-stacks (spanned 20 μm with 1 μm interval) were collected using a ×20 objective, and maximum intensity projections were made for further analysis.

Microglia Quantification

With MorphoLibJ integrated library and plugin in ImageJ, a grey scale attribute opening filter (area minimum, 25 pixels; connectivity, 8) was applied to segment the Iba1-labeled microglia.34 Microglia in the retina were manually counted by three independent individuals, and the average values were used for analysis. In whole mount retina (n = 4 in each group), microglia number was counted within an area of 1.35 mm2 around the optic nerve. For microglia quantification in retinal sections, 15 sections in each group (five eyes in each group and three sections in each eye) encompassing an approximately 0.22 mm2 area (superior and inferior quadrant close to the optic nerve head) were analyzed. The area of inner retina was defined as the region between the inner side of ganglion cell layer (GCL) and the boundary of the OPL and outer nuclear layer (ONL). The area of outer retina was defined as the region between the OPL/ONL boundary and the inner aspect of the RPE.

Microglia Depletion

PLX5622 (1200 parts per million [ppm]) was formulated in AIN-76 chow by Research Diets (New Brunswick, NJ, USA). Standard AIN-76 chow was used as control. BALB/c mice were fed with PLX5622 formulated chow or control chow for 2 weeks before experiments.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Temporal expression changes of Hcar2 and microglia markers were assessed in neural retina at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours after LIR. Based on the temporal analysis, these markers also were measured at 12 hours after LIR, in microglia-depleted retinas. Expression of genes in the Nrf2 and NF-kB pathways was evaluated at 24 hours after LIR. Primers for all genes analyzed are listed in Table 1. Total RNA was extracted from the neural retina using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and converted to cDNA with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Quantitech SYBR Green PCR kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were used to perform qPCR on the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All samples were tested in technical triplicates and the average of the triplicates were used for analysis. Housekeeping gene eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 (Eef2) and TATA-box binding protein (Tbp) were used as reference genes35 and the geometric Ct means of these two genes were used as the internal control.36 Ct values >35 were set as 35. Relative gene expression was analyzed using the 2–ΔCt method.37,38 Fold change ≥2 was considered as biologically significant.

Table 1.

qPCR Primer Sequences and Conditions

|

Gene |

Primer (5′ to 3′) |

Annealing Temp (°C) |

Amplicon Size (bp) |

| Hcar2 | |||

| Fwd | AGCATCATCTTCCTCACCGT | 56 | 192 |

| Rev | ACACAGATATGCCTCGCCAT | ||

| Cd14 | |||

| Fwd | GAAGCAGATCTGGGGCAGTT | 58 | 107 |

| Rev | CGCAGGGCTCCGAATAGAAT | ||

| Mrc1 | |||

| Fwd | GCAAACATTGGGCAGAAGGA | 58 | 191 |

| Rev | CGCCAGCTCTCCACCTATAG | ||

| Nfkb1 | |||

| Fwd | GAGTCACGAAATCCAACGCA | 58 | 217 |

| Rev | AATCCCATGTCCTGCTCCTT | ||

| Nlrp3 | |||

| Fwd | ATGCTGCTTCGACATCTCCT | 58 | 196 |

| Rev | AACCAATGCGAGATCCTGAC | ||

| Casp1 | |||

| Fwd | CGTGGAGAGAAACAAGGAGTG | 56 | 192 |

| Rev | AATGAAAAGTGAGCCCCTGAC | ||

| Il-1β | |||

| Fwd | TGCCACCTTTTGACAGTGATG | 54 | 136 |

| Rev | ATGTGCTGCTGCGAGATTTG | ||

| Nrf2 | |||

| Fwd | CTACTCCCAGGTTGCCCAC | 56 | 241 |

| Rev | CTGCCAAACTTGCTCCATGT | ||

| Hmox1 | |||

| Fwd | ACAGAAGAGGCTAAGACCGC | 60 | 238 |

| Rev | ACAGGAAGCTGAGAGTGAGG | ||

| Gclc | |||

| Fwd | AAGCCTCCTCCTCCAAACTC | 60 | 186 |

| Rev | GGGCCACTTTCATGTTCTCG | ||

| Nqo1 | |||

| Fwd | ATGCTGCCATGTACGACAAC | 60 | 168 |

| Rev | AGACCTGGAAGCCACAGAAA | ||

| Eef2 | |||

| Fwd | TGTCAGTCATCGCCCATGTG | 60 | 123 |

| Rev | CATCCTTGCGAGTGTCAGTGA | ||

| Tbp | |||

| Fwd | TGACCCCTATCACTCCTGCC | 60 | 250 |

| Rev | TGTTCTTCACTCTTGGCTCCTG | ||

Western Blot

Western blot was performed as described previously.39 Proteins in the NF-kB and NRF2 pathways were measured in the neural retina, at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours after LIR. Total protein was extracted from neural retina and 200 μg protein was loaded in 12% acrylamide gels (15% gel for Caspase1). After transfer, membranes were blocked for 1 hour, incubated with primary antibodies (listed in Table 2) overnight, followed by wash and incubation with secondary antibody (1:15,000, goat anti-rabbit IRDye 680RD, P/N925-68071; LICOR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Blots were imaged with an infrared imaging system (Odyssey, Odyssey 2.1 software, LI-COR). The optical density of each band was measured with Odyssey software and normalized to the loading control eEF2, and the values were compared among groups (n = 3 in each group).

Table 2.

Antibodies Used for Western Blot

|

Antibody |

Dilution |

Company (Catalog No.) |

| pNF-kB | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology (3033S) |

| NF-kB | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology (8242S) |

| Caspase1 | 1:1000 | MBL (BV3019-3) |

| pNRF2 | 1:1000 | Abcam (ab76026) |

| HMOX1 | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology (70081S) |

| eEF2 | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology (2332S) |

Histology and Cell Counting

Seven days after light exposure, mouse eyes were enucleated and placed immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde for incubation overnight at room temperature. Eyes then were placed in cassettes and stored in 70% ethanol at room temperature. Oriented eyes were processed and embedded in paraffin for sectioning (Tissue-Tek VIP 6, Tissue-Tek TEC 5; Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA, USA). Sections were cut with a microtome to 4 μm thick, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and viewed on a Leica DMI3000 B microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Central retina (located by the optic nerve head) was imaged from three different mice in each group (PBS + No LIR, MMF + LIR, and PBS + LIR). Photoreceptor nuclei in a ×40 frame were counted and reported.

Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA analysis (with Tukey's multiple comparison tests) in Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. For OCT and ERG measurements, right and left eye values from each mouse were averaged and presented as an individual value. For microglia quantification, the measurements from superior and inferior retina were averaged in each sample. For all data, mean ± SE was calculated and compared among groups. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

MMF Protected Retinal Structure and Function From LIR

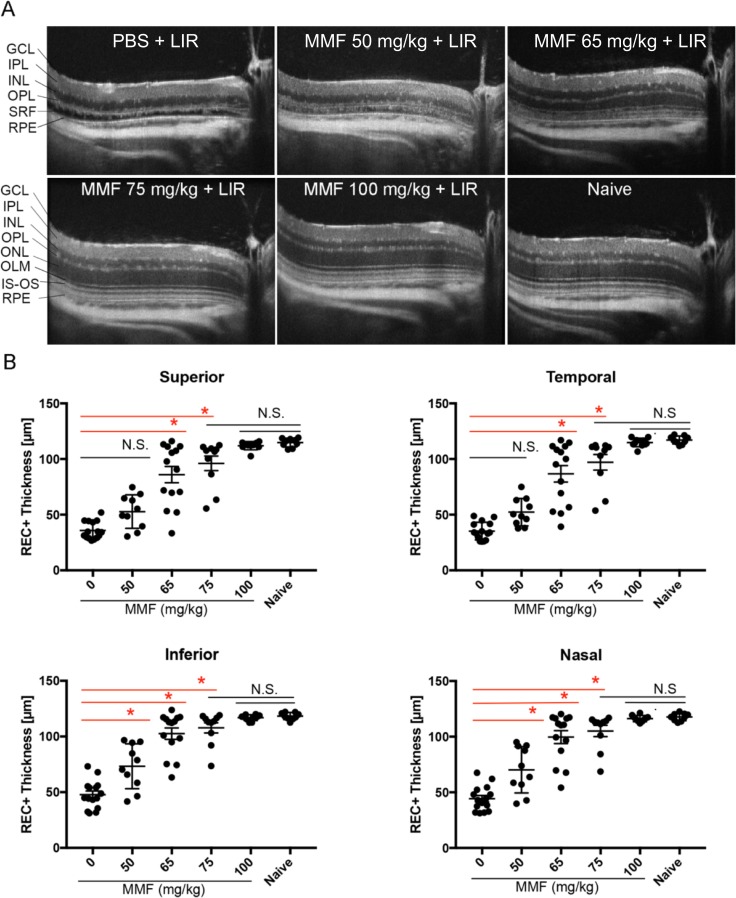

Bright light exposure induced photoreceptor death in PBS-injected mice, as evidenced by the loss of ONL and retinal separation shown in OCT imaging at 7 days after light exposure (Fig. 1A). A single dose of MMF (range, 50–100 mg/kg) before light exposure prevented these morphologic changes in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). MMF treatment 1 hour after light exposure (with either intraperitoneal or intravitreal injection) did not prevent these morphologic changes (Supplementary Figs. S1, S2). Doses between 50 and 100 mg/kg were well-tolerated without apparent side effects. A higher single dose of MMF at 150 or 200 mg/kg (but not 100 mg/kg twice a day) resulted in adverse effects, including decreased grooming, reduced mobility, and decreased body temperature (data not shown).

Figure 1.

MMF protects retinal structure from LIR. (A) Representative SD-OCT scans of the temporal retina. LIR caused ONL depletion and detachment between the RPE and OPL in PBS-treated mice, which was rescued by MMF as the dose increased from 50 to 100 mg/kg. OLM, outer limiting membrane; IS-OS, inner segment and outer segment junction; SRF, subretinal fluid. (B) Quantification of REC+ thickness in all four quadrants of retina showed that 50 and 65 mg/kg MMF were partially protective, whereas 75 and 100 mg/kg MMF provided full protection. Each dot represents the average REC+ thickness from the right and left eye of one mouse (n ≥ 9 in each group). Group average is shown as mean ± SE. N.S., nonsignificant (P > 0.05), *P < 0.05.

After segmentation of SD-OCT images, REC+ thicknesses were quantified in each group (Fig. 1B). Compared to PBS-injected mice, mice treated with 50 mg/kg MMF had a significantly thicker REC+ layer in the inferior and nasal quadrants, but not in the superior and temporal quadrants. MMF at 65 mg/kg significantly preserved REC+ layer thickness in all four retinal quadrants (Fig. 1B, P < 0.05). Mice treated with MMF at 75 and 100 mg/kg exhibited REC+ thicknesses that were not significantly different from naive mice, but greater effects were reached with 100 mg/kg MMF (Fig. 1B, P > 0.05). As the dose of MMF was increased, standard deviations of the groups decreased (Table 3), suggesting a more consistent response. Histology of the retina confirmed OCT results by showing that mice treated with 100 mg/kg MMF have the same average number of photoreceptor nuclei as mice that were not exposed to bright light (Supplementary Fig. S3, P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Retinal Thickness Quantification by OCT Segmentation

|

Group |

n |

REC+ Mean ± SD (μm) |

|||

|

Inferior |

Nasal |

Superior |

Temporal |

||

| 1xPBS + LIR | 15 | 48 ± 13 | 44 ± 11 | 36 ± 8 | 35 ± 8 |

| MMF 50 mg/kg + LIR | 10 | 73 ± 20 | 70 ± 21 | 53 ± 15 | 52 ± 12 |

| MMF 65 mg/kg + LIR | 14 | 103 ± 19 | 100 ± 22 | 86 ± 27 | 87 ± 28 |

| MMF 75 mg/kg + LIR | 10 | 108 ± 15 | 105 ± 16 | 96 ± 21 | 97 ± 22 |

| MMF 100 mg/kg + LIR | 10 | 117 ± 3 | 116 ± 3 | 112 ± 4 | 115 ± 4 |

| Naïve | 9 | 118 ± 3 | 118 ± 3 | 115 ± 4 | 117 ± 4 |

LIR, light-induced retinopathy.

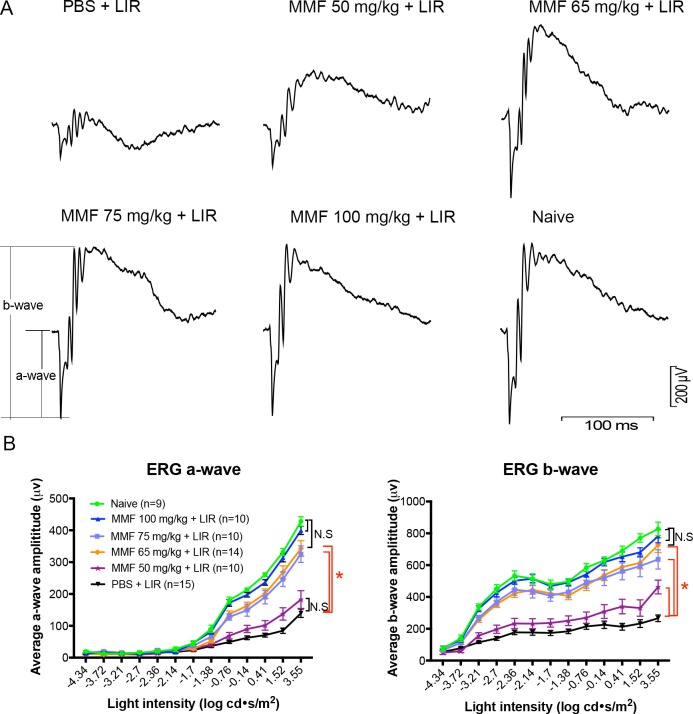

At 8 to 10 days after light exposure, ERGs were recorded. Consistent with OCT measurements, MMF improved ERGs responses in a dose-dependent manner. Light exposure significantly reduced the a- and b-wave amplitudes in PBS-treated mice (Fig. 2A). Mice treated with 50 mg/kg MMF had significantly higher b-wave amplitudes, but nonsignificantly higher a-wave amplitudes than PBS-treated mice (Fig. 2B). MMF at 65 mg/kg and 75 mg/kg improved a- and b-wave amplitudes significantly, but the greatest effect was seen with 100 mg/kg MMF, which exhibited amplitudes indistinguishable from those in naive mice (Fig. 2B, P > 0.05). The average amplitudes of amax and bmax of each group are listed in Table 4. The standard deviations in the groups decreased as the dose of MMF increased.

Figure 2.

MMF preserves retinal function as measured by ERG. (A) ERG traces at the maximum light intensity (3.55 log cd s/m2), recorded 8 to 10 days after light exposure, showed that MMF rescued ERG responses in a dose-dependent manner from 50 to 100 mg/kg. (B) Treatment with 50 mg/kg MMF significantly increased b-wave, but not a-wave amplitudes following LIR. MMF at 65 and 75 mg/kg improved a- and b-wave amplitudes significantly, but the greatest effect was seen with 100 mg/kg MMF. Each dot represents the group average from the right and left eyes of each mouse (n ≥ 9 in each group). Mean ± SE of a- and b-wave amplitudes were plotted at different light intensities in each group. *P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Summary of ERG Amplitudes

|

Group |

n |

amax,rod+cone (μV) | bmax,rod+cone (μV) |

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

||

| 1xPBS + LIR | 15 | 139 ± 50 | 266 ± 80 |

| MMF 50 mg/kg + LIR | 10 | 182 ± 88 | 462 ± 137 |

| MMF 65 mg/kg + LIR | 14 | 343 ± 93 | 727 ± 176 |

| MMF 75 mg/kg + LIR | 10 | 325 ± 82 | 636 ± 192 |

| MMF 100 mg/kg + LIR | 10 | 400 ± 41 | 782 ± 133 |

| Naïve | 9 | 428 ± 44 | 828 ± 128 |

Microglia-Dependent Hcar2 Expression

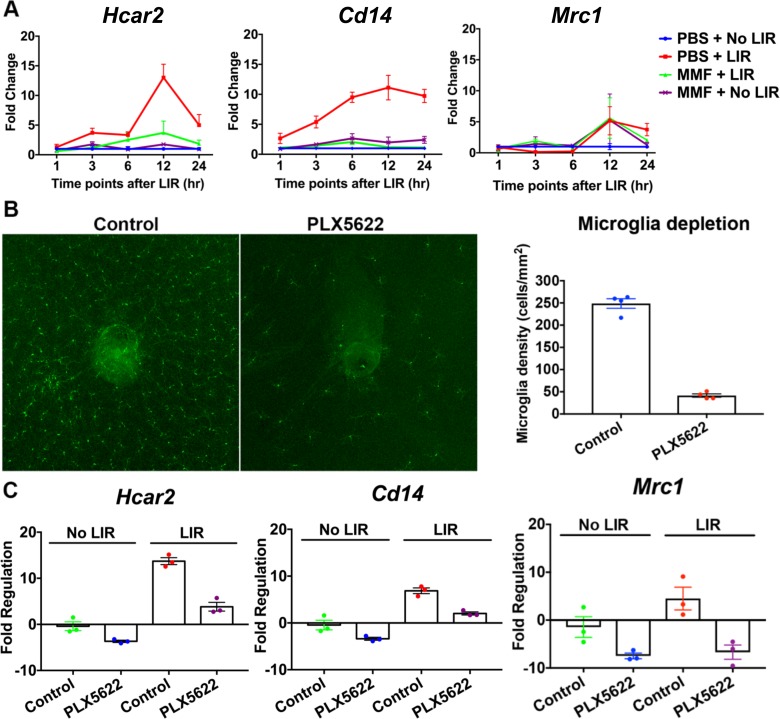

Since MMF is an agonist of the HCAR2 receptor, which is primarily expressed on microglia/macrophages, gene expression levels of Hcar2 and microglia markers were evaluated in the neural retina (n = 3; Fig. 3A). In response to LIR, Hcar2 mRNA level was elevated at 3 to 24 hours after LIR, with the highest level at 12 hours after LIR (13-fold). A similar upregulation was detected for the proinflammatory marker Cd14 from 1 to 24 hours after LIR, with the highest level (11-fold) at 12 hours after LIR. Expression of the anti-inflammatory marker Mrc1 was decreased initially (∼0.2-fold at 3 and 6 hours after LIR), but was increased later at 12 (5.2-fold) and 24 (3.7-fold) hours after LIR. MMF treatment significantly suppressed the upregulation of Hcar2 and Cd14. In the absence of LIR, MMF increased Mrc1 expression at the 12-hour time point (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Microglia-dependent Hcar2 expression. (A) Gene expression changes of Hcar2, Cd14, and Mrc1 from 1 to 24 hours after LIR. LIR upregulated Hcar2 and Cd14 from 1 to 24 hours after LIR. Mrc1 was decreased from 1 to 6 hours after LIR, but was increased from 12 to 24 hours after LIR. MMF treatment significantly suppressed the upregulations of Hcar2 and Cd14. Mean ± SE was reported at each time point, n = 3. (B) Whole mount retina staining with Iba1 showed that with 2 weeks of PLX5622, 77.6% of retinal microglia was depleted. (C) Fold regulation changes of Hcar2, Cd14, and Mrc1 due to microglia depletion. Depletion of microglia with PLX5622 reduced Hcar2 by 3.6-fold in the neural retina without LIR, and attenuated Hcar2 upregulation by LIR from 13.7- to 3.8-fold (12 hours after LIR). PLX5622 also reduced Cd14 (3.3- and 3.4-fold) and Mrc1 (8.1- and 24.3-fold) without LIR and with LIR, respectively. Mean ± SE was reported, n = 3.

To investigate if Hcar2 expression and its upregulation by LIR was dependent on microglia, PLX5622 (an inhibitor of CSF1R) was used to deplete retinal microglia. Following 2 weeks of PLX5622 treatment, 77.6% of retinal microglia were depleted (Fig. 3B). Following microglia depletion, the expression of Cd14 was reduced by 3.3- and 3.4-fold in LIR(-) and LIR(+) mouse retinas, respectively, and Mrc1 expression was reduced by 8.1- and 24.3-fold, respectively (Fig. 3C). Depleting microglia reduced Hcar2 expression by 3.6-fold in the retina without LIR and also attenuated Hcar2 upregulation by LIR, from 13.7-fold in mice with the control diet to 3.8-fold in mice with PLX5622 treatment. These data suggested that HCAR2 expression and its upregulation following LIR occurs primarily in microglia.

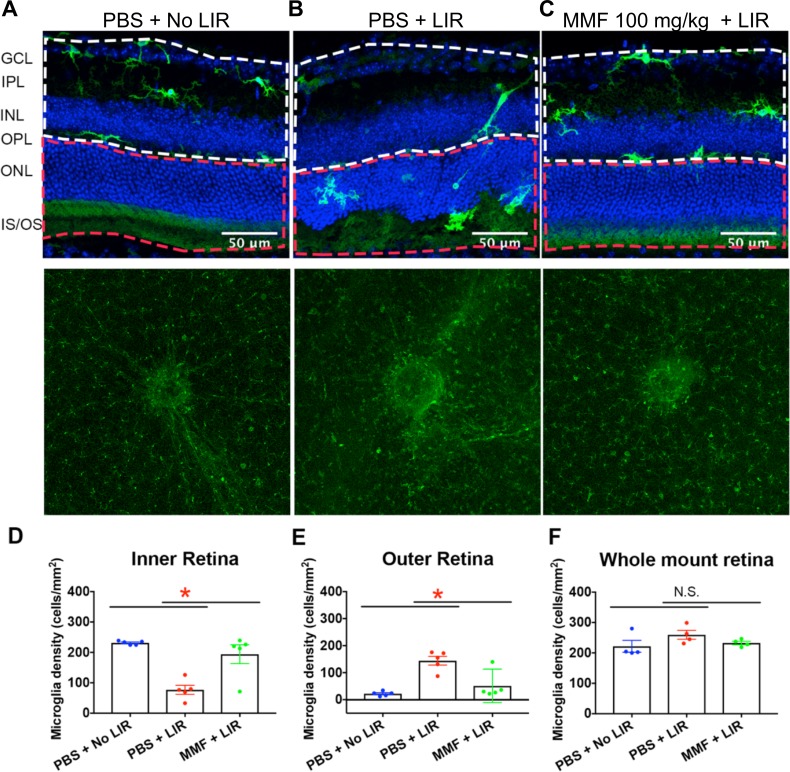

Retinal Microglia Activation was Mitigated in MMF-Treated Animals

At 24 hours after light exposure, microglial morphology and location were assessed in retinal sections and whole mount retina (Figs. 4A–C). Without light exposure, Iba1+ microglia were in a quiescent state, characterized by a dendritic morphology and localization to the IPL, OPL, and GCL of the retina. At 24 hours after light exposure, Iba1+ microglia migrated to the ONL and subretinal space, with amoeboid morphology characterized by larger soma and shortened processes. In the MMF-treated mice, Iba1+ microglia predominantly localized to the IPL and OPL and exhibited ramified morphologies, similar to that seen in mice retina without light exposure.

Figure 4.

Retinal microglia activation was inhibited in MMF-treated animals. (A) At 24 hours after LIR, representative retinal sections and whole mount retinas stained with Iba1 demonstrated microglia translocation and density in the retina, respectively. Without LIR, Iba1-labeled microglia with ramified processes (green) were located in the IPL and OPL. (B) LIR induced microglia translocation to the ONL and microglia contained shortened processes. (C) MMF inhibited microglia migration and morphologic transformation. The white dotted line defines the area of inner retina, and the red dotted line defines the area of outer retina. (D, E) Quantification of microglia changes in retinal sections showed that LIR significantly decreased microglia density in the inner retina, and increased it in the outer retina, which was attenuated by MMF treatment. In each group, 15 sections (three sections in each mouse and five mice in each group) were analyzed. (F) In the whole mount retina, microglia density was not significantly changed by LIR or MMF treatment (n = 4). Each dot represents the microglia density in one mouse. Group average is shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05.

To quantify microglia translocation, microglia were counted in the inner and outer retinas respectively, within an area of 0.22 mm2 close to optic nerve in 15 sections/group (three sections in each mouse and five mice in each group). Light exposure significantly increased microglia density in the outer retina (Fig. 4D), but decreased it in the inner retina (Fig. 4E).

To evaluate if the number of microglia in the whole retina changed in response to LIR or MMF treatment, microglia were counted in whole mount retinas (four mice in each group), within a 1.35 mm2 area around the optic nerve. The results showed that by 24 hours, LIR did not significantly increase microglia density. Furthermore, microglia density was similar between the MMF + LIR and PBS + No LIR groups (Fig. 4F). These results are most consistent with microglial translocation from the inner to the outer retina.

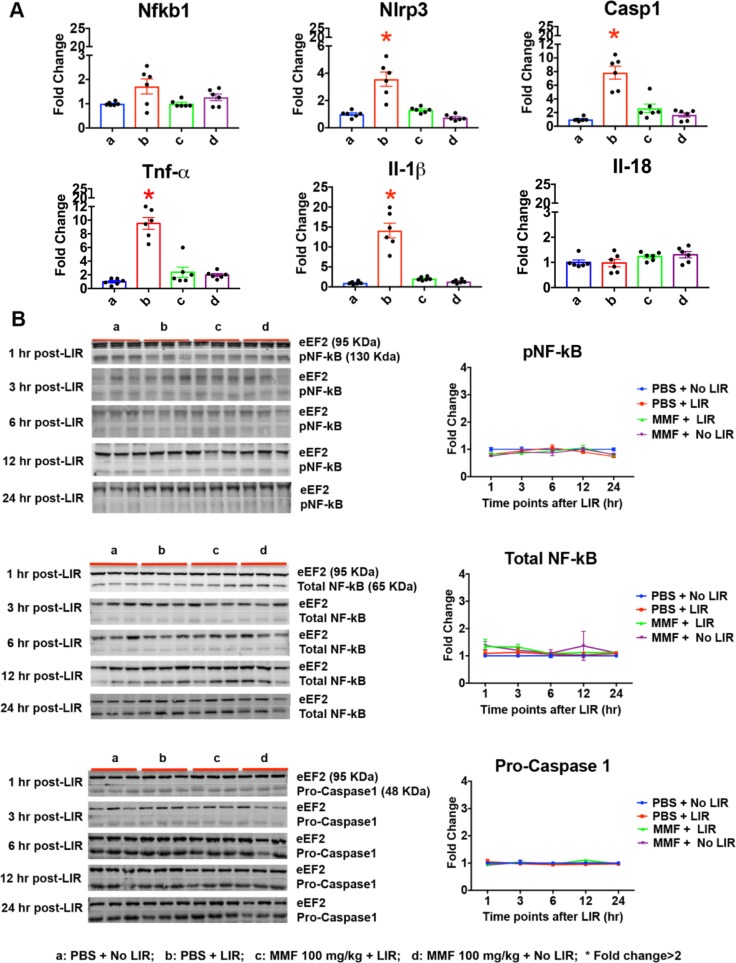

Retinal Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Were Reduced in MMF-Treated Animals

At 24 hours after light exposure, LIR upregulated genes in the NFkB pathway including: Nlrp3 (3.6-fold), Casp1 (7.8-fold), Il-1β (14.1-fold), and Tnf-α (9.5-fold). All increases were significantly suppressed in MMF-treated animals (Fig. 5A). However, protein levels of pNF-kB (ser536), total NF-kB, and Pro-Caspase1 remained unchanged from 1 to 24 hours after light exposure in treated and untreated animals (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Retinal inflammation was reduced in MMF-treated animals. (A) At 24 hours after LIR, qPCR analysis of mRNA in the neural retina showed that the induction of proinflammatory genes Nlrp3 (3.6-fold), Casp1 (7.8-fold), Il-1β (14.1-fold), and TNF-α (9.5-fold) were suppressed in MMF-treated retinas. These experiments were replicated twice with n = 3. (B) Western blot analysis pNF-kB (ser536), total NF-kB, and Pro-Caspase1, from 1 to 24 hours after LIR. There were no significant changes in protein levels. Fold change was shown as mean ± SE, n = 3. *Fold change ≥ 2.

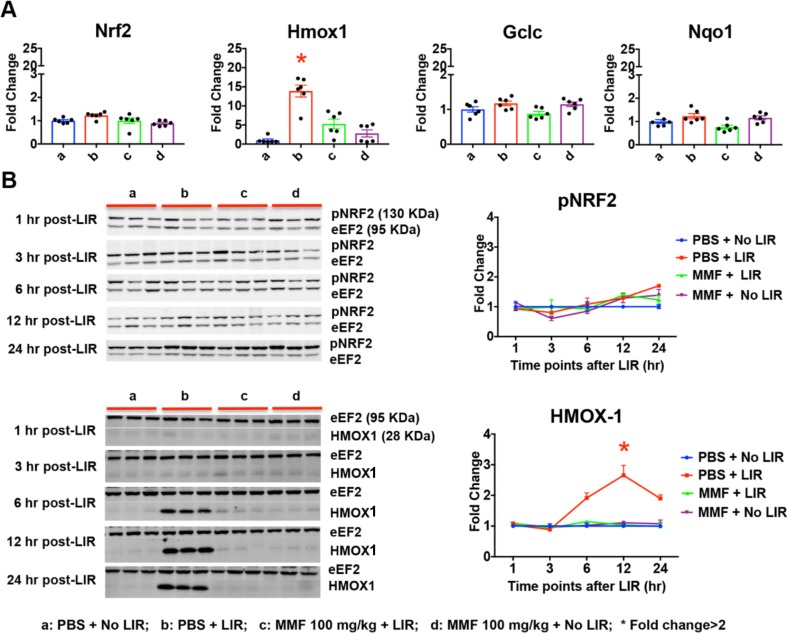

In the Nrf2 pathway, light exposure upregulated Hmox1 mRNA levels (13.9-fold) at 24 hours following light exposure, which was attenuated in MMF-treated animals (Fig. 6A). Levels of Nrf2, Gclc, and Nqo1 were not significantly altered by light exposure or MMF treatment. Western blot analysis confirmed LIR-mediated increases in HMOX1 at the protein level (∼2-, 3-, and 2-fold at 6, 12, and 24 hours after LIR, respectively; Fig. 6B). In MMF-treated animals, retinal HMOX1 protein levels were maintained at baseline from 1 to 24 hours after LIR. LIR slightly, but not significantly increased pNRF2 (ser40) at 24 hours after LIR (1.7-fold), while MMF treatment maintained pNRF2 level at baseline (1.2-fold; Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Retinal oxidative stress was reduced in MMF-treated animals. (A) At 24 hours after LIR, Hmox1 mRNA level was upregulated (13.9-fold) by LIR, which was significantly attenuated in MMF treated retinas. Nrf2, Gclc, and Nqo1 did not show significant changes. All qPCR data was replicated twice with n = 3. (B) Western blot analysis showed that HMOX1 protein level was increased at 6 (1.9-fold), 12 (2.7-fold), and 24 (1.9-fold) hours after LIR, which was attenuated in MMF-treated retinas. Protein level of pNRF2 (ser40) was not significantly changed from 1 to 24 hours after LIR. Fold change was shown as mean ± SE, n = 3. *Fold change ≥ 2.

Discussion

In this study, MMF protected photoreceptors from degeneration induced by LIR structurally and functionally, and in a dose-dependent manner. The receptor of MMF, Hcar2, was upregulated by LIR and this change was dependent on the presence of microglia in the neural retina. MMF-mediated neuroprotection was associated with inhibition of retinal microglia activation and attenuation of markers related to oxidative stress and inflammation.

MMF is an agonist of the HCAR2 receptor, which is expressed in peripheral macrophages and microglia in mouse brain.14 Although expression of Hcar2 has been reported in the RPE of mouse retina, expression in retinal microglia has not been reported previously to our knowledge.40,41 In this study, Hcar2 mRNA was detected in the neural retina and was upregulated by light exposure. However, we were unable to detect HCAR2 by immunohistochemistry in the neural retina or RPE, using multiple antibodies and staining conditions. This led us to investigate if depleting microglia in the retina affects Hcar2 expression. Depletion of microglia in the retina by PLX5622 reduced Hcar2 expression and also attenuated Hcar2 upregulation induced by light exposure. Previous studies have reported that PLX5622 (an antagonist of CSF1R) selectively depletes microglia without affecting peripheral macrophages.42 These data suggested that Hcar2 expression and its upregulation by LIR in the neural retina is microglia-dependent.

Hcar2 upregulation in response to light exposure may be an intrinsic protective mechanism against light damage to the retina. The physiologic ligand for HCAR2 is β-hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body naturally derived from acetoacetate.43 Ketones reduce the production of reactive oxygen species and free radicals in the mitochondria by increasing the NAD/NADH ratio,44 and also promote the production of neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF.45 Given its higher affinity for HCAR2 than β-hydroxybutyrate,46 MMF may be able to exert a greater neuroprotective effect, alleviating the need to upregulate Hcar2 levels.

Previous in vitro studies have reported that MMF modulates microglia activation through Hcar2 signaling.16 However, modulation of microglia by MMF in the retina has not been thoroughly investigated. In this study, MMF treatment inhibited microglia activation (as shown in retinal sections with Iba1 staining) and suppressed a pro-inflammatory marker (Cd14), while increasing the anti-inflammatory marker (Mrc1). This result is consistent with studies showing that MMF can induce cultured microglial cells treated with LPS to switch from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory configurations.16 Microglia activation is a critical component of neuroinflammation, which potentiates the degeneration of photoreceptors and the RPE in dry AMD and IRDs.28,29 These results were consistent with previous studies showing that MMF is a powerful inhibitor of microglia activation,16 and also suggested that MMF is a potential therapeutic agent for retinal degeneration.

Modulation of NF-kB and Nrf2 pathways has been implicated previously in MMF-mediated neuroprotection.16,21 In this study, at the mRNA level, LIR led to an upregulation of genes in the NF-kB and Nrf2 pathways, which was attenuated in MMF-treated retinas. At the protein level, changes in HMOX1 were confirmed. However, protein levels of pNF-kB, total NF-kB, pro-Caspase1, and pNRF2 were not significantly changed. Although we tried to assess NF-kB and NRF2 activation through key phosphorylation sites,47,48 changes of these transcription factors may be too small to be measured. This is different from the changes of the downstream effectors, which were amplified through the cascade reactions. Activity of these transcription factors may need to be measured by their translocation to the nucleus. Activation of Caspase1 usually is demonstrated by increases in Caspase1 gene expression and the cleavage of Caspase1 protein. We showed an upregulation of Caspase1, but we were unable to detect the cleaved-Caspase1. These data were consistent with previous studies that reported increased mRNA level of Caspase1 in the retina with LIR, but were unable to detect the cleaved-Caspase1 protein.49,50 The role of Caspase1 in light-induced photoreceptor cell death remains unclear. Overall, these data suggested a reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress associated with MMF treatment, but does not support a direct modulation on these pathways by MMF. As shown in the naive retinas, MMF itself did not lead to expression changes of genes in these pathways. Since previous studies have shown these mechanisms in microglia cell culture, it is possible that harvesting retinal microglia will be required to investigate downstream HCAR2 signaling.

Neuroprotection was achieved only when MMF was administered systemically before bright light exposure. Systemic and ocular administration of MMF after bright light exposure did not result in any significant protection of the retina. This suggested that MMF can prevent, but not restore photoreceptor cell death induced by light exposure. Our lab and others have reported that combination therapies with Gαi agonists and Gαq antagonists provide additive or synergistic protection due to the activation of multiple protective pathways.5,51 Combination therapies will allow for the use of subtherapeutic doses of each monotherapy to minimize side effects and improve efficacy.5,51 Future studies will investigate lower doses of MMF with Gαq antagonists to further optimize MMF therapy for retinal degeneration.

In summary, this study showed that MMF completely protected the retina in mice with LIR, with inhibition of microglia activation, inflammation, and oxidative stress in the retina. The retinal protection and targeted molecular profile suggested that MMF could be a potential therapy for retinal degenerations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by unrestricted departmental funding from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY, USA); Grant P30 EY010572 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA); K08 Career Development Award (K08 EY021186, MEP); Alcon Young Investigator Award, Foundation Fighting Blindness; Enhanced Research and Clinical Training Award (CD-NMT-0914-0659-OHSU, MEP); Career Development Award from Research to Prevent Blindness (MEP); and Career-Starter Research Grant, Knights Templar Eye Foundation (DJ).

Disclosure: D. Jiang, None; R.C. Ryals, None; S.J. Huang, None; K.K. Weller, None; H.E. Titus, None; B.M. Robb, None; F.W. Saad, None; R.A. Salam, None; H. Hammad, None; P. Yang, None; D.L. Marks, None; M.E. Pennesi, None

References

- 1.Miller JW, Bagheri S, Vavvas DG. Advances in age-related macular degeneration understanding and therapy. US Ophthalmic Rev. 2017;10:119–130. doi: 10.17925/USOR.2017.10.02.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell S, Bennett J, Wellman JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65-mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:849–860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31868-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coyner AS, Ryals RC, Ku CA, et al. Retinal neuroprotective effects of flibanserin, an FDA-approved dual serotonin receptor agonist-antagonist. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tullis BE, Ryals RC, Coyner AS, et al. Sarpogrelate, a 5-HT2A Receptor antagonist, protects the retina from light-induced retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:4560–4569. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thampi P, Rao HV, Mitter SK, et al. The 5HT1a receptor agonist 8-Oh DPAT induces protection from lipofuscin accumulation and oxidative stress in the retinal pigment epithelium. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Palczewska G, Mustafi D, et al. Systems pharmacology identifies drug targets for Stargardt disease-associated retinal degeneration. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5119–5134. doi: 10.1172/JCI69076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Palczewski K. Systems pharmacology links GPCRs with retinal degenerative disorders. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56:273–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collier RJ, Patel Y, Martin EA, et al. Agonists at the serotonin receptor (5-HT(1A)) protect the retina from severe photo-oxidative stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2118–2126. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biswal MR, Ahmed CM, Ildefonso CJ, et al. Systemic treatment with a 5HT1a agonist induces anti-oxidant protection and preserves the retina from mitochondrial oxidative stress. Exp Eye Res. 2015;140:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Okano K, Maeda T, et al. Mechanism of all-trans-retinal toxicity with implications for stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5059–5069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.315432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubey D, Kieseier BC, Hartung HP, et al. Dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: rationale, mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15:339–346. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1025755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cada DJ, Levien TL, Baker DE. Dimethyl fumarate. Hosp Pharm. 2013;48:668–679. doi: 10.1310/hpj4808-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang H, Lu JY, Zheng X, Yang Y, Reagan JD. The psoriasis drug monomethylfumarate is a potent nicotinic acid receptor agonist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:562–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillard GO, Collette B, Anderson J, et al. DMF, but not other fumarates, inhibits NF-kappaB activity in vitro in an Nrf2-independent manner. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;283:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parodi B, Rossi S, Morando S, et al. Fumarates modulate microglia activation through a novel HCAR2 signaling pathway and rescue synaptic dysregulation in inflamed CNS. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:279–295. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1422-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miglio G, Veglia E, Fantozzi R. Fumaric acid esters prevent the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated and ATP-triggered pyroptosis of differentiated THP-1 cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;28:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Zhou W, Zhang X, et al. Dimethyl fumarate ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine experimental colitis by activating Nrf2 and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;112:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Assmann JC, Krenz A, et al. Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 mediates dimethyl fumarate's protective effect in EAE. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2188–2192. doi: 10.1172/JCI72151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng H, Li H, Sheehy A, Cullen P, Allaire N, Scannevin RH. Dimethyl fumarate alters microglia phenotype and protects neurons against proinflammatory toxic microenvironments. J Neuroimmunol. 2016;299:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scannevin RH, Chollate S, Jung MY, et al. Fumarates promote cytoprotection of central nervous system cells against oxidative stress via the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341:274–284. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.190132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho H, Hartsock MJ, Xu Z, He M, Duh EJ. Monomethyl fumarate promotes Nrf2-dependent neuroprotection in retinal ischemia-reperfusion. J Neuroinflamm. 2015;12:239. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0452-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buendia I, Michalska P, Navarro E, Gameiro I, Egea J, Leon R. Nrf2-ARE pathway: an emerging target against oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;157:84–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linker RA, Lee DH, Ryan S, et al. Fumaric acid esters exert neuroprotective effects in neuroinflammation via activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Brain. 2011;134:678–692. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Promsote W, Powell FL, Veean S, et al. Oral monomethyl fumarate therapy ameliorates retinopathy in a humanized mouse model of sickle cell Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;25:921–935. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pennesi ME, Neuringer M, Courtney RJ. Animal models of age related macular degeneration. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:487–509. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coppieters F, Ascari G, Dannhausen K, et al. Isolated and syndromic retinal dystrophy caused by biallelic mutations in RCBTB1, a gene implicated in ubiquitination. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma W, Zhao L, Fontainhas AM, Fariss RN, Wong WT. Microglia in the mouse retina alter the structure and function of retinal pigmented epithelial cells: a potential cellular interaction relevant to AMD. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao L, Zabel MK, Wang X, et al. Microglial phagocytosis of living photoreceptors contributes to inherited retinal degeneration. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1179–1197. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao S, Wang JC, Gao J, et al. CFH Y402H polymorphism and the complement activation product C5a: effects on NF-kappaB activation and inflammasome gene regulation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:713–718. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rana T, Shinde VM, Starr CR, et al. An activated unfolded protein response promotes retinal degeneration and triggers an inflammatory response in the mouse retina. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1578. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viringipurampeer IA, Metcalfe AL, Bashar AE, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation drives bystander cone photoreceptor cell death in a P23H rhodopsin model of retinal degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:1501–1516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerur N, Hirano Y, Tarallo V, et al. TLR-independent and P2X7-dependent signaling mediate Alu RNA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in geographic atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7395–7401. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis BM, Salinas-Navarro M, Cordeiro MF, Moons L, De Groef L. Characterizing microglia activation: a spatial statistics approach to maximize information extraction. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01747-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eissa N, Hussein H, Wang H, Rabbi MF, Bernstein CN, Ghia JE. Stability of reference genes for messenger rna quantification by real-time pcr in mouse dextran sodium sulfate experimental colitis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ku CA, Ryals RC, Jiang D, et al. The role of ERK1/2 activation in sarpogrelate-mediated neuroprotection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:462–471. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin PM, Ananth S, Cresci G, Roon P, Smith S, Ganapathy V. Expression and localization of GPR109A (PUMA-G/HM74A) mRNA and protein in mammalian retinal pigment epithelium. Mol Vis. 2009;15:362–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu AL, Birke K, Lorenz RL, Welge-Lussen U. Constitutive expression of HCA(2) in human retina and primary human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:487–492. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.848900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilla AM, Diekmann H, Fischer D. Microglia are irrelevant for neuronal degeneration and axon regeneration after acute injury. J Neurosci. 2017;37:6113–6124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0584-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laffel L. Ketone bodies: a review of physiology, pathophysiology and application of monitoring to diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:412–426. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199911/12)15:6<412::aid-dmrr72>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maalouf M, Sullivan PG, Davis L, Kim DY, Rho JM. Ketones inhibit mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species production following glutamate excitotoxicity by increasing NADH oxidation. Neuroscience. 2007;145:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sleiman SF, Henry J, Al-Haddad R, et al. Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate. Elife. 2016;5:e15092. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blad CC, Ahmed K, AP IJ, Offermanns S. Biological and pharmacological roles of HCA receptors. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;62:219–250. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385952-5.00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bloom DA, Jaiswal AK. Phosphorylation of Nrf2 at Ser40 by protein kinase C in response to antioxidants leads to the release of Nrf2 from INrf2, but is not required for Nrf2 stabilization/accumulation in the nucleus and transcriptional activation of antioxidant response element-mediated NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44675–44682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christian F, Smith EL, Carmody RJ. The regulation of NF-kappaB subunits by phosphorylation. Cells. 2016;5:E12. doi: 10.3390/cells5010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donovan M, Cotter TG. Caspase-independent photoreceptor apoptosis in vivo and differential expression of apoptotic protease activating factor-1 and caspase-3 during retinal development. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1220–1231. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimm C, Wenzel A, Hafezi F, Reme CE. Gene expression in the mouse retina: the effect of damaging light. Mol Vis. 2000;6:252–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Y, Palczewska G, Masuho I, et al. Synergistically acting agonists and antagonists of G protein-coupled receptors prevent photoreceptor cell degeneration. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra74. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aag0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.