To the Editor:

Despite evidence that hydroxyurea is effective for sickle cell anemia (SCA), implementation of the “maximum tolerated dose” regimen in adults is poor.1 We recently reported a study of “fixed low-dose” hydroxyurea (500 mg/day) for adults with SCA in Ibadan, Nigeria.2 Here we compare the outcomes of “fixed low-dose” hydroxyurea in Nigeria with “maximum tolerated dose” hydroxyurea in the United States and Canada as reported in the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea (MSH).3,4 The MSH was the seminal trial conducted in the 1990’s that led to FDA approval of hydroxyurea for SCA. Responses to “fixed low-dose” and “maximum tolerated dose” hydroxyurea appear to be similar. We propose that these two regimens be compared in a prospective trial in adults with SCA.

Hydroxyurea for SCA increases hemoglobin F and reduces pain crises, acute chest syndrome and blood transfusions.5 The agent is initiated at 15 mg/kg/day in adults followed by dose escalations up to 35 mg/kg/day if tolerated – the “maximum tolerated dose” approach of the MSH.3,4 Doses in this range may enhance survival,6 however neutropenia and thrombocytopenia are limitations to achieving maximal dose, frequent blood count monitoring is required, and treatment interruption is usually necessary.4,5 This limits the use of hydroxyurea in parts of Africa where frequent blood monitoring is not feasible.7 In the United States and United Kingdom, the complexity and need for frequent monitoring of the recommended “maximum tolerated dose” regimen cause primary care providers to hesitate to prescribe hydroxyurea8 and create barriers to compliance.9

In the original MSH study, pain crises in SCA adults decreased during the first 12 weeks of hydroxyurea 15 mg/kg/day before dose escalation and before maximal increase in F-cells.4 ENREF 21 The MSH investigators stated in 1996 that “Lower doses may produce the same beneficial effect as the potentially hazardous doses we used here, and it is important that both doses and dose schedules be studied further.”3 These considerations led us to conduct a trial of hydroxyurea 500 mg/day in 48 SCA adults in Ibadan, Nigeria – a “fixed low-dose” approach- the results of which we have published.2 The design of the Ibadan study was in keeping with the recent statement of Ware and colleagues that an important question for hydroxyurea use in Africa “is whether fixed low-dose therapy (10–20 mg/kg/day) is more practical than escalation to maximum tolerated dose (20–30 mg/kg/day) because medication optimization requires frequent monitoring, dose adjustments, and clinical expertise”.7 While analyzing the results, we noticed that outcomes in the Ibadan study were similar to those reported in the MSH study.3

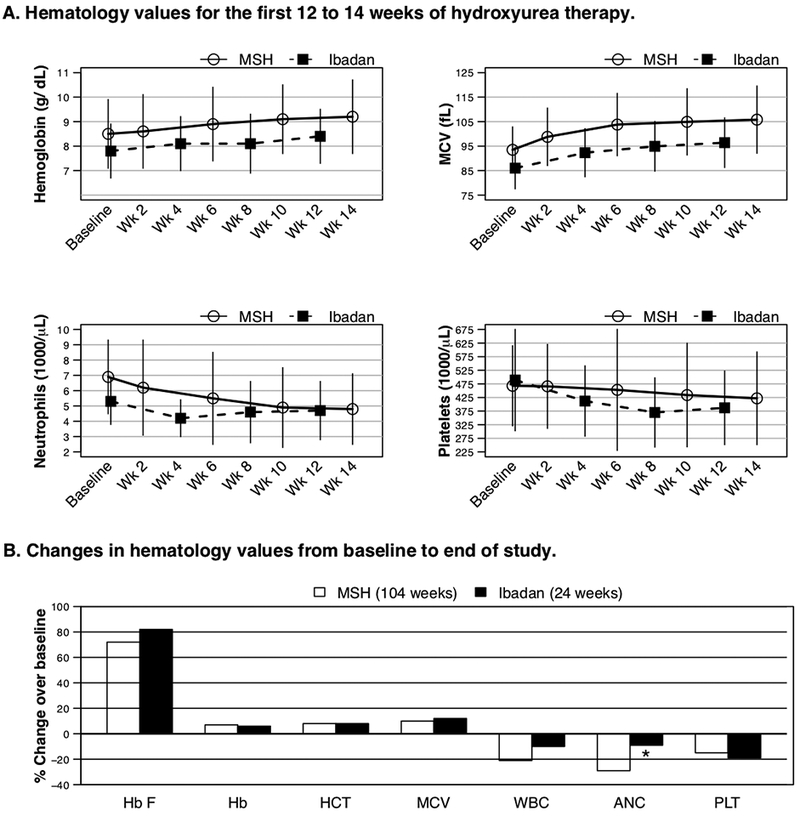

In the present report, we compare responses in 48 patients from the Ibadan study who were assigned to receive hydroxyurea for 24 weeks2 to responses in 152 MSH patients randomized to hydroxyurea for 104 weeks.3 Sixty percent of the Ibadan patients and 48% of the MSH patients were males. Seventy-nine percent of the Ibadan patients and 51% of the MSH patients were 18–29 years of age. Moderate to severe disease based on ≥3 crises/year was an entrance criterion for the MSH but not the Ibadan study. Baseline hematologic values for participants from the MSH study and the Ibadan study are shown in Table 1. Over the first 12–14 weeks of hydroxyurea therapy, responses in hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and platelets were similar in the two studies. The initial decline in neutrophils was less marked in the Ibadan cohort, but the MSH patients started with a higher neutrophil count, and at 12–14 weeks the mean neutrophil counts were similar- in the 4700–4800 range (Figure 1A). Twenty-nine (60%) of the Ibadan patients had an increase in the MCV of ≥10 fL.

Table 1.

Baseline and end of study values (mean ± SD) for the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea (MSH), which gave maximum tolerated dose, and the Ibadan study, which gave a fixed low-dose of 500 mg/day.

| MSH (N = 152) |

Ibadan (N = 48) |

P (com-parison of change between cohorts) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Study (104 weeks) | Change in mean value | Baseline | End of Study (24 weeks) | Change in mean value | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 8.5 ± 1.4 | 9.1 ± 1.5 | 0.6 | 7.8 ± 1.1 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 24.9 ± 4.4 | 27.0 ± 5.0 | 2.1 | 24.9 ± 3.3 | 26.8 ± 3.5 | 1.9 | 0.8 |

| MCV (fL) | 94 ± 9 | 103 ± 14 | 9 | 86 ± 8 | 96 ± 10 | 10 | 0.7 |

| White blood cells (1000/μL) | 12.6 ± 3.4 | 9.9 ± 3.1 | -2.7 | 10.2 ± 2.4 | 9.2 ± 2.6 | -1.0 | 0.002 |

| Neutrophils (1000/μL) | 6.9 ± 2.4 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | -2.0 | 5.3 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | -0.5 | <0.001 |

| Platelets (1000/μL) | 468 ± 147 | 399 ± 124 | -69 | 489 ± 186 | 397± 143 | -92 | 0.4 |

| Hemoglobin F (%) | 5.0 ± 3.5 | 8.6 ± 6.8 | 3.6 | 4.9 ± 3.0 | 8.9 ± 5.3 | 4.0* | 0.8 |

n=20

Figure 1. A. Effect of two starting doses of hydroxyurea on hematology measures.

Shown are mean and SD values for hemoglobin, MCV, neutrophils and platelets over the first 12 to 14 weeks of hydroxyurea treatment in the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea (MSH) cohort (14 weeks of treatment, 15 mg/kg/day, n=152)_ENREF 213 and the Ibadan cohort (12 weeks of treatment, 10 mg/kg/day, n=38). Changes from baseline were comparable between the two approaches in hemoglobin, MCV and platelets but the neutrophils had less of a decline in the Ibadan cohort. B. Effect of two approaches to hydroxyurea dosing on end of study values for hemoglobin F and hematology measures.At end of study, changes in hemoglobin F and other hematology measures were comparable between the MSH study, which targeted “maximum tolerated dose” hydroxyurea, and the Ibadan study, which administered 500 mg/day (10 mg/kg/day) as a “fixed low-dose” regimen. Hb F (hemoglobin F), HB (hemoglobin), HCT (hematocrit), MCV (mean corpuscular volume), WBC (white blood cells), ANC (neutrophils), PLT (platelets).

In the MSH study, hydroxyurea was interrupted because of neutrophil count <2000/mm3 in 79 patients (54%),3,4 while in the Ibadan study one patient (2%) developed a neutrophil count <2000/mm3 (P<0.0001).2 Neutrophils in the Ibadan cohort were above the stopping criteria for that study and increased to >2000/mm3 with continued hydroxyurea therapy. Platelets <80,000/mm3 developed in three patients (2%) in the MSH study3,4 and two patients (4%) in the Ibadan study (P=0.6).2 The low platelet counts in the Ibadan study were attributed to acute malaria and responded to antimalarial treatment while hydroxyurea was continued.2 At the end of the studies (24 weeks Ibadan study and 104 weeks MSH study), responses in hemoglobin F, hemoglobin, MCV and platelets were similar. The declines in white blood cell and neutrophil counts in the Ibadan cohort were significantly less, but the mean ending values were similar in the two cohorts (Table 1 and Figure 1BThe median (range) dose of hydroxyurea per body weight in the Ibadan patients was 10 (7–14) mg/k g/day. The final dose of hydroxyurea in the MSH patients was 20 (2.5–35) mg/kg/day.3

In the MSH study, the mean ± SD rate of crisis (acute pain treated in emergency department or hospital, acute chest syndrome, priapism, hepatic sequestration) throughout the study was 1.2±2 per three months in the “maximum tolerated dose” hydroxyurea arm compared to 1.8±2.6 per three months in the placebo arm (P=0.006), a 33% reduction.3 In the Ibadan patients, the rate of prospectively recorded non-infectious complications (pain crisis, priapism, severe anemia, headache, neurologic abnormality or death) was 2.81 episodes per 24 patient-months during “fixed low-dose” hydroxyurea versus 4.78 episodes per 24 patient-months during observation without hydroxyurea (P=0.065). This corresponds to a 41% lower acute complication rate in the “fixed low-dose” hydroxyurea period. The single death occurred during observation. The rate of infections (mostly fever or malaria) was 1.29 episodes per 24 patient- months during hydroxyurea versus 1.33 episodes per 24 patient-months during observation (P=0.8).

Increase in hemoglobin F during hydroxyurea therapy is related to the plasma hydroxyurea level, which is dose-dependent.10 The MSH analyzed patients receiving hydroxyurea according to quartiles of hemoglobin F response after two years of treatment.11 Half of the patients had little or no increase in hemoglobin F and their crisis rates did not decrease compared to placebo.3,11 The other half had mean hemoglobin F increases of 1.7 to 2.8-fold above baseline and their mean crisis rates were 0.3 to 0.4-fold lower than the placebo group.3,11 Forty-nine percent of the patients in the quartiles without increase in hemoglobin F were receiving hydroxyurea 25–35 mg/kg/day and 42% were receiving <15 mg/kg/day. By comparison, 25% in the quartiles with increases in hemoglobin F were receiving 25–35 mg/kg/day while 31% were receiving <15 mg/kg/day.11 Therefore, the response in hemoglobin F to hydroxyurea appears to depend not only on dose, but also on a complex interplay of absorption, compliance and baseline physiologic variables.11

There are limitations to the comparison of the Ibadan study and the MSH. The MSH cohort was more female, older, and from a different historical era and continent. It was a multicenter randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled study of patients with moderate-severe disease that lasted 104 weeks. The Ibadan study is a single center, open-label study with the enrolled patients as their own controls that lasted 28 weeks; a specific threshold of number of vaso-occlusive crises per year was not required. Nevertheless, a comparison of the two cohorts raises the possibility that a “fixed low-dose” hydroxyurea regimen in adults, one 500 mg capsule per day, may allow for similar clinical benefits as the “maximum tolerated dose” regimen. The simpler regimen would help increase compliance, decrease health care costs and expand the number of health care providers delivering safe and effective SCA care in both low and high resource environments. A “fixed low-dose” hydroxyurea regimen would have low risk to induce cytopenias2 and be ideal to test in combination therapy trials because of the constant dose and safety. Other reports are supportive of this approach. Investigators in India reported that hydroxyurea 10 mg/kg/day decreased pain episodes and transfusions in SCA children and adults.12–14 In Oman, SCA children treated with hydroxyurea 10–15.9 mg/kg/day had similar decreases in pain episodes and improvement in hematologic measures as patients treated with 16–26 mg/kg/day.15

A range of doses of hydroxyurea are under investigation for SCA children in sub-Saharan Africa at the present time. The placebo-controlled NOHARM trial (NCT01976416) and the open label REACH trial (NCT01966731) trial recently reported that mean doses of 19–25 mg/kg per day were well-tolerated and led to reductions in vaso-occlusive events. The SPRING (NCT02560935) and SPRINT (NCT02675790) trials are comparing “fixed low-dose” (10 mg/kg/day) to moderate-dose (20 mg/kg/day) hydroxyurea for stroke prevention in Nigeria. The NOHARM-MTD study in Uganda (NCT03128515) features blinded randomization between moderate-dose (20 mg/kg/day) and “maximum tolerated dose” (25–30 mg/kg/day) hydroxyurea. Comparable investigations of hydroxyurea for SCA adults in Africa are not in progress. We do not recommend fixed low-dose hydroxyurea as routine therapy for SCA adults in Africa at the present time, but we do believe that it is time to extend studies of hydroxyurea dosage to adults with SCA. We propose that a randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety of the “fixed low-dose” and “maximum tolerated dose” regimens be conducted in SCA adults in both Africa and Western countries. Such a trial should be a high priority; it conceivably could lead to “fixed low-dose” hydroxyurea as the standard approach for SCA adults worldwide.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by Grant 2013140 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (B.O.T. and V.R.G.). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views or polices of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Stettler N, McKiernan CM, Melin CQ, Adejoro OO, Walczak NB. Proportion of adults with sickle cell anemia and pain crises receiving hydroxyurea. JAMA 2015;313:1671–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tayo BO, Akingbola TS, Saraf SL, Shah BN, Ezekekwu CA, Sonubi O, Hsu LL, Cooper RS, Gordeuk VR. Fixed Low-Dose Hydroxyurea for the Treatment of Adults with Sickle Cell Anemia in Nigeria. Am J Hematol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charache S, Barton FB, Moore RD, Terrin ML, Steinberg MH, Dover GJ, Ballas SK, McMahon RP, Castro O, Orringer EP. Hydroxyurea and sickle cell anemia. Clinical utility of a myelosuppressive “switching” agent. The Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:300–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, McMahon RP, Bonds DR. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platt OS. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1362–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzhugh CD, Hsieh MM, Allen D, Coles WA, Seamon C, Ring M, Zhao X, Minniti CP, Rodgers GP, Schechter AN, Tisdale JF, Taylor JGt. Hydroxyurea-Increased Fetal Hemoglobin Is Associated with Less Organ Damage and Longer Survival in Adults with Sickle Cell Anemia . PLoS One 2015;10:e0141706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGann PT, Hernandez AG, Ware RE. Sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa: advancing the clinical paradigm through partnerships and research. Blood 2017;129:155–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandow AM, Panepinto JA. Hydroxyurea use in sickle cell disease: the battle with low prescription rates, poor patient compliance and fears of toxicities. Expert review of hematology 2010;3:255–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward J, Lewis N, Tsitsikas DA. Improving routine outpatient monitoring for patients with sickle-cell disease on hydroxyurea. BMJ Open Qual 2018;7:e000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charache S, Dover GJ, Moore RD, Eckert S, Ballas SK, Koshy M, Milner PF, Orringer EP, Phillips G, Jr., Platt OS, et al. Hydroxyurea: effects on hemoglobin F production in patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood 1992;79:2555–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg MH, Lu ZH, Barton FB, Terrin ML, Charache S, Dover GJ. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia: determinants of response to hydroxyurea. Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea. Blood 1997;89:1078–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel DK, Mashon RS, Patel S, Das BS, Purohit P, Bishwal SC. Low dose hydroxyurea is effective in reducing the incidence of painful crisis and frequency of blood transfusion in sickle cell anemia patients from eastern India. Hemoglobin 2012;36:409–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sethy S, Panda T, Jena RK. Beneficial Effect of Low Fixed Dose of Hydroxyurea in Vaso-occlusive Crisis and Transfusion Requirements in Adult HbSS Patients: A Prospective Study in a Tertiary Care Center . Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2018;34:294–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain DL, Apte M, Colah R, Sarathi V, Desai S, Gokhale A, Bhandarwar A, Jain HL, Ghosh K. Efficacy of fixed low dose hydroxyurea in Indian children with sickle cell anemia: a single centre experience . Indian pediatrics 2013;50:929–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharef SW, Al-Hajri M, Beshlawi I, Al-Shahrabally A, Elshinawy M, Zachariah M, Mevada ST, Bashir W, Rawas A, Taqi A, Al-Lamki Z, Wali Y. Optimizing Hydroxyurea use in children with sickle cell disease: low dose regimen is effective. Eur J Haematol 2013;90:519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]