Abstract

Shigella spp. constitutes some of the key pathogens responsible for the global burden of diarrhoeal disease. With over 164 million reported cases per annum, shigellosis accounts for 1.1 million deaths each year. Majority of these cases occur among the children of the developing nations and the emergence of multi-drug resistance Shigella strains in clinical isolates demands the development of better/new drugs against this pathogen. The genome of Shigella flexneri was extensively analyzed and found 4,362 proteins among which the functions of 674 proteins, termed as hypothetical proteins (HPs) had not been previously elucidated. Amino acid sequences of all these 674 HPs were studied and the functions of a total of 39 HPs have been assigned with high level of confidence. Here we have utilized a combination of the latest versions of databases to assign the precise function of HPs for which no experimental information is available. These HPs were found to belong to various classes of proteins such as enzymes, binding proteins, signal transducers, lipoprotein, transporters, virulence and other proteins. Evaluation of the performance of the various computational tools conducted using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis and a resoundingly high average accuracy of 93.6% were obtained. Our comprehensive analysis will help to gain greater understanding for the development of many novel potential therapeutic interventions to defeat Shigella infection.

Keywords: hypothetical protein, in silico, NCBI, ROC curve, Shigella

Introduction

Shigella, refers to a genus of gram-negative facultative anaerobes that belongs to members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and is the causative agent of shigellosis, a severe enteric infection, one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among children in developing nations. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) classified Shigella as the second leading cause of diarrheal deaths on a global scale in 2015 [1]. Shigellosis leads to the recurrent passing of small, bloody mucoidal stools with synchronous abdominal cramps and tenesmus caused by ulceration of the colonic epithelium [2]. In malnourished children, Shigella infection may lead to a vicious cycle of further impaired nutrition, frequent infection and growth retardation resulting from protein loss enteropathy [3].

The Shigella genus is divided into four species: Shigella flexneri, Shigella boydii, Shigella sonnei, and Shigella dysenteriae. These are further classified into serotypes based on biochemical differences and variations in their O-antigen [4]. A total of 19 different serotypes of S. flexneri have been reported so far by various research groups [5]. Among the four Shigella species, shigellosis is predominantly caused by S. flexneri in the developing world especially in Asia, and is responsible for approximately 10% of all diarrheal episodes among children of <5 years [6]. Recent multicenter study in Asia revealed that the incidence of this disease might even exceed previous estimations, due to Shigella DNA being detectable in up to one third of the total culture negative specimens [7]. Currently, no effective vaccine with the ability to confer adequate protection against the many different serotypes of Shigella has been developed and made available. Existing antimicrobial treatments are becoming compromised in terms of efficacy due to increased antibiotic resistance, soaring cost of treatment, and persistence of poor hygiene and unsanitary conditions in the developing world.

A particular study conducted on numerous isolates of Shigella collected over a time span of 10 years, multi-drug resistance (MDR) were found to be exhibited by 78.5% of the isolates. 2% of the isolates were found to harbor genetic information capable of conferring resistance to azithromycin, a final resort antimicrobial agent for shigellosis [8]. On the other hand, a recent whole genome analysis of a particular strain of S. flexneri revealed 82 distinct chromosomal antibiotic resistance genes while successive re-sequencing platforms elucidated several distinct single nucleotide polymorphisms that contributed to eventual MDR [9]. Therefore, the development of new drugs has risen to become a subject of immense magnitude to not only shorten the medication period but also to treat MDR shigellosis. The genome sequence of S. flexneri serotype 2a strain 2457T, available in the NCBI database consists of 4,599,354 bp in a single circular chromosome containing 4,906 genes encoding 4,362 proteins and has G + C content of 50.9% [10]. Among these, the functions of 674 proteins have not been experimentally determined till date and are termed as hypothetical proteins (HPs). A HP is one that has been predicted to be encoded by an identified open reading frame, but for which there is a lack of experimental evidence [11]. Nearly half of the proteins in most genomes belong to the class of HPs and this class of proteins presumably have their own importance to complete genomic and proteomic platform of an organism [12, 13]. Precise annotation of the HPs of particular genome leads to the discovery of new structures as well as new functions, and elucidating a list of additional protein pathways and cascades, thus completing our incomplete understanding on the mosaic of proteins [13]. HPs may possibly play crucial roles in disease progression and survival of pathogen [11, 14]. Furthermore, novel HPs may also serve as markers and pharmacological targets for development of new drugs and therapies [15]. Functions of HPs from several pathogenic organisms have been already reported using a plethora of sequence and structure based methods [14, 16, 17].

Functional annotation of HPs utilizing advanced bioinformatics tools is a well-established platform in current proteomics [18]. Cost and time efficiency of these methods also favoring their preference over contemporary in vitro techniques [19]. In this study, we have used several well optimized and up to date bioinformatics tools to assign functions of a number of HPs from the genome of S. flexneri with high precision [20]. Functional domains were considered as the basis to infer the biological functions of HPs in this case. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis [21] was used for evaluating the performance of bioinformatics tools executed in our study. We also measured the confidence level of the functional predictions on the basis of bioinformatics tools employed during the course of the investigation [22]. We believe that this analysis will expand our knowledge regarding the functional roles of HPs of Shigella and provide an opportunity to unveil a number of potential novel drug targets [17].

Methods

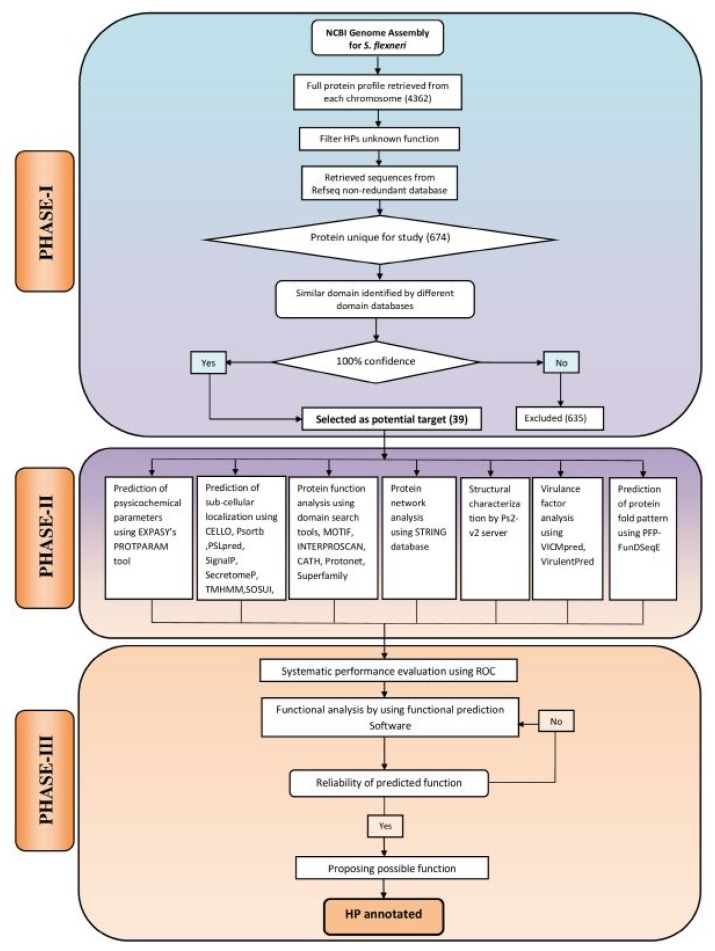

The computational algorithm used for this study has been illustrated in Fig. 1. The entire work scheme has been divided into three phases namely, phase I, II and III. Phase I involves the characterization and sequence retrieval of the HPs, following the analysis of the S. flexneri genome. Phase II comprises of the annotation of various functional parameters using well optimized series of tools. The probable functions of the characterized HPs were predicted by the integration of various functional predictions. In phase III, an approach was made for systematic performance evaluation of various bioinformatics tools used in this study. In this case, S. flexneri protein sequences with known function were used as control. Finally, expert knowledge was applied for annotation of HPs at a considerable degree of confidence.

Fig. 1.

Computational algorithm used for annotating function of 39 hypothetical proteins (HPs) from Shigella flexneri. The framework has been divided into three phases: PHASE I, sequence retrieval from online databases; PHASE II, the extensive analysis of sub-cellular localization, physicochemical parameters, virulence, function and domain present in HPs; PHASE III, assessment of the predicted functions using the protein with known function from S. flexneri and reliable prediction of possible functions of HPs.

Phase I

Accession of genome and sequence retrieval

Complete genome sequence of S. flexneri 2a str. 2457T was retrieved from NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/) and was found to code for a total of 4,362 proteins (accessed July 5, 2017). Fasta sequences of the complete coding sequence of 682 proteins, characterized as HPs were retrieved from UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/). Finally, a total of 674 proteins were retained for downstream analysis following exclusion of duplicates.

Analysis of the conserved domains

Domains are often identified as recurring (sequence or structure) units, and can be thought of as distinct functional and/or structural units of a protein. During molecular evolution, it is assumed that domains may have been utilized as building blocks and have encountered recombination to modulate protein function [23]. A domain or fold might also exhibit a higher degree of conservancy when compared with the entire sequence [24].

In our study, five bioinformatics tools namely: CDD-BLAST (Conserved Domain Database-Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) [25–27], PFAM [28], HmmScan [29], SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) [30], and SCANPROSITE [31] were used. These tools are able to search for the defined conserved domains in the targeted protein sequences and further assist in the classification of putative proteins in a particular protein family. HPs analyzed by five aforementioned function prediction web tools revealed the variable results when searched for the conserved domains in hypothetical sequences. Therefore, different confidence levels were assigned on the basis of collective results of these web-tools. One hundred percentage confidence level was considered upon obtaining the same results from the five distinct tools. Finally, we obtained 39 such proteins from 674 primary collected proteins, which were taken for further analysis (Supplementary Table 1).

Phase II

Physicochemical characterization

Theoretical physiochemical parameters such as molecular weight, isoelectric point, aliphatic index, instability index and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) of these HPs were analyzed using ProtParam server of the Expasy tools (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). Results of this analysis have been listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Determination of sub-cellular localization

For the identification of a protein as a drug or vaccine candidate, determination of the sub-cellular localization of the protein becomes particularly important. Surface membrane protein can be served as a potential vaccine target while cytoplasmic proteins may act as promising drug targets [32]. We used CELLO [33], PSORTb [34], and PSLpred [35] for the denotation of sub-cellular localization of the query proteins. TMHMM, SOSUI, and HMMTOP were applied for the prediction of query proteins for being a membrane protein, based on Hidden Markov Model [36–38]. SingnalP 4.1 [39] was used to predict the signal peptide and SecretomeP 2.0 [40] were utilized for the identification of proteins involved in non-classical secretory pathway. Results of these predictions are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

Functional prediction of the query proteins

Various tools were used for precise functional assignments of all 39 HPs from S. flexneri (described in Table 1) such as CDD-Blast, Pfam, HmmScan, SMART, Scanprosite, MOTIF [41], INTERPROSCAN [42], CATH [43], SUPERFAMILY [44], and Protonet [45]. Results of these analyses have been outlined in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

Table 1.

List of annotated Hconf proteins from Shigella flexneri

| No | Protein name | Protein function |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | WP_005053355.1 | Peptidase, C92 family |

| 2 | WP_000092054.1 | DUF1615/lipoprotein |

| 3 | WP_001382892.1 | DUF3251/lipoprotein YajI/immunoglobulin like domain |

| 4 | WP_005053036.1 | Lipoprotein_16/uncharacterized lipoprotein |

| 5 | WP_000779831.1 | lipoprotein chaperone (YscW) |

| 6 | WP_011110552.1 | YbfN-like lipoprotein |

| 7 | WP_001269672.1 | LPS-assembly lipoprotein RlpB (LptE) |

| 8 | WP_001247854.1 | Topoisomerases, DnaG-type primases, Hedgehog/intein domain |

| 9 | WP_000070107.1 | ATP-binding cassette transporter |

| 10 | WP_000224274.1 | MOSC beta barrel domain/2Fe-2S iron-sulfur cluster binding domain |

| 11 | WP_000749269.1 | YceI-like domain |

| 12 | WP_001125713.1 | YcgL domain |

| 13 | WP_001043881.1 | GAF domain |

| 14 | WP_001295493.1 | Endoribonuclease L-PSP/YjgFfamily |

| 15 | WP_000691930.1 | Domain of unknown function (DUF333) |

| 16 | WP_000597196.1 | Glycine zipper 2TM domain |

| 17 | WP_000248636.1 | AI-2E family transporter/permease |

| 18 | WP_000755956.1 | SPFH domain/Band 7 family |

| 19 | WP_001237866.1 | YecR-like lipoprotein |

| 20 | WP_000454701.1 | TerC family/Transporter associated domain/CBS domain |

| 21 | WP_000003197.1 | von Willebrand factor type A domain |

| 22 | WP_005049020.1 | Uncharacterized lipoprotein YehR |

| 23 | WP_048814497.1 | Leucine rich repeat protein/NEL or novel E3 ligase domain |

| 24 | WP_000301054.1 | Lipopolysaccharide kinase (Kdo/WaaP) |

| 25 | WP_000266171.1 | Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) |

| 26 | WP_000589825.1 | Outer membrane protein (ompA) like domain/membrane lipoprotein |

| 27 | WP_005051685.1 | LysM (lysin-like motif)/peptidase family M23 |

| 28 | WP_001387238.1 | DNA repair protein RadC-like JAB domain |

| 29 | WP_000248097.1 | Carrier protein (CP) domain and phosphopantetheine attachment site |

| 30 | WP_000848528.1 | Lipoprotein leucine-zipper |

| 31 | WP_000189314.1 | GIY-YIG nuclease domain |

| 32 | WP_001297375.1 | DNA repair protein RadC-like JAB domain |

| 33 | WP_000858193.1 | yiaA/B two helix domain |

| 34 | WP_001296791.1 | Autotransporter beta-domain |

| 35 | WP_000778795.1 | Acetyltransferase (GNAT) domain |

| 36 | WP_001205243.1 | Xylose isomerase-like TIM barrel (AP_endonuc_2) |

| 37 | WP_001238362.1 | Lipocalin-like domain |

| 38 | WP_000943980.1 | Glutathionylspermidine synthase |

| 39 | WP_000132640.1 | Toxin SymE/SpoVT-AbrB domain |

The computational prediction of the structure of a protein from its amino acid sequences greatly facilitates the subsequent prediction of its function [46]. An online server PS2-v2 (PS Square version 2) [47], a template based method were used to predict the structure of the HPs. The modeling of proteins using this online server further substantiated the function of HPs. Besides, PFP-FunDSeqE [48] has been used to elucidate the protein fold patterns based on a combination of functional domain information and evolutionary information (Table 2).

Table 2.

Different types of folds identified in Shigella flexneri

| No. | Fold type | Accession number |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Viral coat and capsid proteins | WP_005053355.1, WP_000691930.1 |

| 2 | TIM-barrel | WP_000092054.1, WP_001247854.1, WP_001295493.1, WP_000266171.1, WP_001297375.1, WP_000943980.1, WP_000132640.1 |

| 3 | Ferredoxin-like | WP_001382892.1, WP_000003197.1, WP_000301054.1 |

| 4 | 4-Helical up-and-down bundle | WP_005053036.1, WP_000779831.1, WP_001269672.1 |

| 5 | DNA-binding 3-helical bundle | WP_011110552.1, WP_000589825.1, WP_001387238.1, WP_000848528.1, WP_000189314.1 |

| 6 | Small inhibitors, toxins, lectins | WP_000070107.1, WP_000454701.1, WP_048814497.1, WP_001205243.1 |

| 7 | Belta-grasp | WP_000224274.1 |

| 8 | Cupredoxins | WP_000749269.1, WP_000248636.1, WP_005051685.1 |

| 9 | Thioredoxin-like | WP_001125713.1 |

| 10 | Flavodoxin-like | WP_001043881.1 |

| 11 | Trypsin-like serine proteases | WP_000597196.1 |

| 12 | OB-fold | WP_000755956.1, WP_001237866.1, WP_000858193.1, WP_000778795.1 |

| 13 | Immunoglobulin-like | WP_005049020.1 |

| 14 | EF-hand | WP_000248097.1 |

| 15 | ConA-like lectin/glucanases | WP_001296791.1 |

| 16 | Lipocalins | WP_001238362.1 |

Virulence factors analysis

Virulence factors (VFs) are described as potent targets for developing drugs because it is essential for the severity of infection [49]. VICMpred [50] and Virulentpred [51] tools were employed to predict VFs from protein sequences with an accuracy of 70.75% and 81.8%, respectively.

Functional protein association networks

The function and activity of a protein are often modulated by other proteins with which it interacts. Therefore, understanding of protein-protein interactions serve as valuable leads for predicting the function of a protein. In this investigation, we had employed STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins, https://string-db.org/) [52] to predict protein interactions partners of HPs. To predict functional association, only highest confidence score partner proteins were chosen in this study.

Phase III

Performance assessment

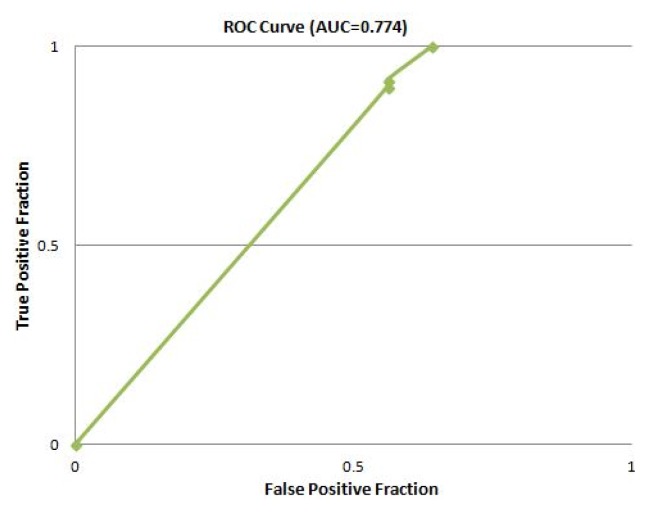

The predicted functions of HPs from S. flexneri and the accuracy of associated tools were validated using the ROC curve analysis. In this analysis, the diagnostics efficacy is evaluated at six levels where 1 and 0 classified as true positive and true negative respectively as binary numerals. In addition, the integers (2, 3, 4, and 5) were used as confidence ratings for each case. The ROC curves were carried out using 25 S. flexneri proteins with known function as control and were compared with the results obtained for the 39 HPs (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). The results were submitted to web-based calculator for the ROC curves [53] in “format 1” form and the program thereby calculated the ROC curves. The results were expressed in terms of accuracy (Ac), sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp) and the area under the curve (AUC) [54]. The average accuracy of the employed pipeline was found 93.6% (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Table 3.

List of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and ROC area of various bioinformatics tools used for predicting function of Hconf proteins from Shigella flexneri obtained after ROC analysis

| No. | Software name | Accuracy of prediction (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | ROC area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BLAST | 100 | 100 | n/a | n/a |

| 2 | Pfam | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| 3 | HmmScan | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| 4 | SMART | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| 5 | Scanprosite | 72 | 100 | 12.50 | 0.662 |

| 6 | MOTIF | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| 7 | Interproscan | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| 8 | CATH | 80 | 100 | 16.70 | 0.539 |

| 9 | SUPERFAMILY | 84 | 100 | 20 | 0.54 |

| 10 | ProtoNet | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| 11 | Average | 93.6 | 100 | 64.35 | 0.774 |

ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.774) for average accuracy of prediction.

Results and Discussion

Sequence analysis

Sequences of all the 674 HPs were analyzed for identification of the functional domains using five bioinformatics tools namely CDD-BLAST, Pfam, HmmScan, SMART, and SCANPROSITE. If the given five tools indicated the same domains for a protein, we considered it as 100% confidence level. In our study, all the five tools mentioned above revealed 39 such proteins and hence were grouped together. Only these HPs having 100% confidence level were considered for further analyses and termed as highly confident (Hconf) proteins. From the rest of the 635 proteins, no specific conserved domains were found for a total of 257 proteins. For other HPs (n = 378), specific domains were identified using several of these tools. To know accurate function of these proteins further studies are required.

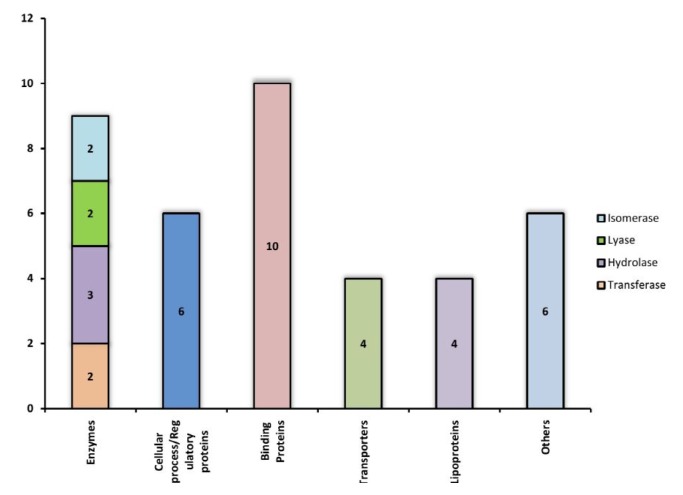

The function of each of these 39 Hconf were successfully assigned by using different online tools, listed in Table 1. All sequence analyses were compiled and categorized into various functional classes constituting 9 enzymes, 10 binding proteins, 4 transporters, 4 lipoproteins, 6 which are involved in various cellular processes, while 6 proteins were predicted to exhibit miscellaneous functions (Fig. 3). Various functional classes of these classified Hconf proteins are described below.

Fig. 3.

Hypothetical proteins classified into different groups based on their functions.

Enzymes

Enzymes are key players in many leading biochemical processes in the living system and may facilitate the survival of pathogens in the host and making it viable for the course of infection. A total of 9 proteins out of 39 (23%) of our annotated Hconfs were characterized as enzymes. Among these, two proteins were characterized as transferases, among which, WP_000301054.1 is a lipopolysaccharide kinase (Kdo/WaaP), involved in the formation of outer membrane (OM) of gram negative bacteria and is encoded by the Waap gene. The OM protects cells from toxic molecules and is important for survival during infection and is required for virulence of the pathogen [55]. According to reports made by Delucia [55], the depletion of WaaP gene was seen to halt the growth of the bacteria suggesting that WaaP is essential to produce the full-length lipopolysaccharide, recognized by the OM [49]. Therefore, WaaP may result in a potent target for the development of novel antimicrobial agents. The other transferase, protein WP_000778795.1 was found to consist of an acetyltransferase (GNAT) domain that uses acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) to transfer an acetyl group to a substrate, a reaction implicated in various functions for the development of antibiotic resistance of bacteria [56].

Three enzymes were predicted to be hydrolases, which plays key role in the invasion of the host tissue and evading the host defense mechanism and are thus associated with various VFs [57]. For instance, WP_005051685.1 marks the lysin-like motif/peptidase family M23, is found in proteins from viruses, bacteria, fungi, plants and mammals. It is present in bacterial extracellular proteins including hydrolases, adhesins and VFs such as protein A from Staphylococcus aureus. We report WP_001295493.1 protein as the endoribonuclease/YjgF family active on single-stranded mRNA that inhibits protein synthesis by cleaving mRNA [58]. YjgF family members are enamine/imine deaminases that hydrolyze reactive intermediates released by pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzymes, including threonine dehydratase [59]. It has also been reported in the inhibition of transaminase B in Salmonella [60].

Among the other enzymes predicted, there has been two isomerase and one lyase enzyme. WP_001247854.1 constitutes the toprim (topoisomerase-primase),a catalytic domain involved in breakage and rejoining of DNA strand [61]. WP_001205243.1 marks the Xylose isomerase-like TIM barrel involved in the myo-inositol catabolism pathway [62]. Lyases also play a key role in bacterial pathogenesis due to their involvements in various biosynthesis processes. WP_000943980.1 was found to demonstrate synthase activity that causes hydrolysis of ATP with the formation of an amide bond between spermidine and the glycine carboxylate of glutathione. In the pathogenic trypanosomatids, this reaction is the penultimate step in the biosynthesis of the antioxidant metabolite, and is a resounding target for target mediated drug design [63]. The WP_000454701.1 protein was found to be a cystathionine b-lyase, an enzyme which forms the cystathionine intermediate in cysteine biosynthesis and may be considered as the target for pyridiamine anti-microbial agents [64].

Binding proteins

Ten proteins annotated as binding proteins among which 1 RNA binding, 3 protein binding, 3 lipid binding, 1 metal binding, 1 peptidoglycan binding, and 1 adhesion protein have been predicted. WP_000132640.1 protein was predicted to be SymE (SOS-induced yjiW gene with similarity to MazE). It has been reported to involve in inhibiting cell growth, decrease protein synthesis and increase RNA degradation and thus exhibit a vital role in the survival and propagation of pathogen in the host [65, 66]. Despite not manifesting any functional homology with other type I toxin proteins, SymE belongs to the type I toxin-antitoxin system. Its function resembles that of type II toxins such as MazF, which is able to perform the cleavage of mRNA in a ribosome independent manner. However, SymE shares homology to the AbrB-fold superfamily proteins such as MazE, which acts as transcriptional factors and antitoxins in various type II TA modules [67]. It seems probable that SymE has evolved into an RNA cleavage protein with toxin-like properties from a transcription factor or antitoxin [66]. In our study, we reported WP_000003197.1 as von Willebrand factor with a type A domain which has been reported responsible for various blood disorders [68–70]. The association of type A domain makes it liable to be involved in various significant activities such as cell adhesion and immune defense [71]. On the other hand, WP_000755956.1 has been predicted to belong to the band-7 protein family that comprises of a diverse set of membrane-bound proteins characterized by the presence of a conserved domain [72]. The exact function of this domain is not known, but concurrent reports from animal and bacterial stomatin-type proteins demonstrate the ability of binding to lipids and in the assembly of membrane-bound oligomers that form putative scaffolds [73]. We have also predicted WP_001269672.1 and WP_000749269.1 as the lipid binding domain called lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-assembly lipoprotein LptE and the YceI-like domain respectively. The LPS transport machinery is composed of LptA, LptB, LptC, LptD, and LptE. LptE forms a complex with LptD, which is involved in the assembly of LPS in the outer leaflet of the OM [74]. This OM is an effective permeability barrier that protects the cells from toxic compounds, such as antibiotics and detergents, thus conferring the bacteria with the capability to adapt and consequently inhabit several different and often hostile environments. Among the binding prtoteins, WP_000266171.1 was found to be a tetratricopeptide repeat containing protein which is involved in protein-protein interactions and thus plays an important role in virulence [75].

Cellular processes/regulatory proteins

A total of 6 HPs have been predicted to be involved in various cellular and regulatory mechanisms, which are vital cognates in the pathogenesis of S. flexneri and thus can be treated as possible drug targets [76]. For example, WP_000189314.1 predicted to be a member of the GIY-YIG family involved in many cellular processes including DNA repair and recombination, transfer of mobile genetic elements, and restriction of incoming foreign DNA [77, 78].

WP_001387238.1 and WP_001297375.1 have been found to be RadC-like domain belonging to the JAB superfamily of metalloproteins [79]. In most instances, this domain shows fusions to an N-terminal Helix-hairpin-Helix (HhH) domain and may also be function as a nuclease [79]. WP_000848528.1 has been predicted to be a leucine-zipper found in the enterobacterial OM lipoprotein LPP [80]. It is likely that this domain is involved in protein-protein interaction via subsequent oligomerization. WP_000597196.1 and WP_048814497.1 have been respectively found to be a Glycine zipper 2TM domain found in the Rickettsia genus and leucine-rich repeat involved in a variety of biological processes, including signal transduction, cell adhesion, DNA repair, recombination, transcription, RNA processing, disease resistance, apoptosis, and the immune response [81].

Lipoprotein

Bacterial lipoproteins are a set of membrane proteins with many different functions. Due to this broad-ranging functionality, these proteins have a considerable significance in many phenomena, from cellular physiology through cell division and virulence [82]. Lipoprotein of gram-negative bacteria is essential for growth and division [83]. In our analysis, we report a total of 4 lipoproteins from the group of HPs predicted in this study. It has been also revealed that lipoproteins may function as vaccines [82]. The knowledge of these facts may be utilized for the generation of novel countermeasures to bacterial diseases [82].

Transport

In our findings, we report the prediction of HP WP_000070107.1 to be a member of the ATP-binding cassette superfamily, largest of all protein families with a diversity of physiological functions [84]. It has recently been identified that these proteins may be involved in virulence and are essential for intracellular survival of pathogens [85]. We have found protein WP_001296791.1 to be an auto-transporter of the YhjY type involved in DNA repair [86]. Protein WP_001238362.1 has been found to exhibit the function of transport of nutrients, control of cell regulation, pheromone transport, cryptic coloration and in the enzymatic synthesis of prostaglandins. An example a protein with such function is the retinol-binding protein 4, which transfers retinol from liver to peripheral tissues [87].

Other proteins

Six HPs have been predicted to exhibit miscellaneous functions where most of them are protein with unknown function. Among them, WP_001382892.1 and WP_000691930.1 have been preicted to be domains of unknown function and are found in a number of bacterial proteins. WP_001125713.1 has been found to be YcgL domain with conserved class of small proteins widespread in gammaproteo bacteria. This group of proteins contain a 85-residue domain of unknown function and two alpha-helices and four beta-strands in the sequential arrangement [88]. We have also predicted WP_001237866.1 and WP_005049020.1 as YecR and YehR like family of lipoproteins found in bacteria and viruses and are functionally uncharacterized.

Virulent proteins

Gram-negative bacteria undergo frequent genomic alterations and consequent evolutions thus increasing their virulence inside the host environment [89]. We have found 2 HPs that showed positive virulence scores servers among the Hconf proteins. These have been listed in Supplementary Table 8. It had already been hypothesized that targeting VF provides a better therapeutic intervention strategy against bacterial pathogenesis [89]. Predicted HPs having virulent characteristics thus provide powerful target-based therapies for the mitigation of an existing infection and are further considered as an adjunct therapy to existing antibiotics, or potentiators of the host immune response [90].

ROC curve

The average accuracy of the employed pipeline was identified 93.6% in our analysis which indicated that outcomes of the functional annotation of HPs were predicted with a high degree of confidence. We have also found sensitivity of 100% and specificity 64.3% for the tools used in this study. Finally, area under the curve was found to be 0.774. AUC is an effective way to summarize the overall diagnostic accuracy of the test. It takes values from 0 to 1, where 0.7 to 0.8 is considered acceptable.

Conclusion

Using an innovative in silico approach, all 674 HPs from S. flexneri were primarily analyzed and then using the ROC analysis and confidence level measurements of the predicted results the functions of the 39 HPs were precisely predicted with a reasonably high degree of confidence and thereby were successfully characterized. Following this, the validation of the functions of these proteins were carried out by using different approaches including structure based PS2-v2 server, sub-cellular localization and physicochemical parameters. These are important for distinguishing the HPs from the rest of the protein. The protein-protein interaction also gave insights in elucidation of the involvement of such proteins in various metabolic pathways. Moreover, some virulence proteins had also been detected which are essential for the survival of this pathogen. This in silico approach for functional annotation of the HPs can be further utilized in drug discovery for characterizing putative drug targets for other clinically important pathogens. The outcomes of ROC analysis indicated high reliability of bioinformatics tools used in this study. Hence, the functional annotation of HPs is reliable and can be further utilized for other experimental research.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to core donors which provide unrestricted support to icddr,b for its operations and research. Current donors providing unrestricted support include: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh; Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), and the Department for International Development, UK (DFID). We gratefully acknowledge these donors for their support and commitment to icddr,b’s research efforts.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions

Conceptualization: MAG

Data curation: MAG, SM, SMF, MGK

Formal analysis: MAG, SM

Funding acquisition: MAG, MRI, HR, SD

Methodology: SM, MGK, PP, MRI, HR, SD

Writing – original draft: MAG, MM, TA

Writing – review & editing: MAG, MM, TA

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Supplementary Information

References

- 1.GBD Diarrhoeal Diseases Collaborators Estimates of global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:909–948. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30276-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathan MM, Mathan VI. Ultrastructural pathology of the rectal mucosa in Shigella dysentery. Am J Pathol. 1986;123:25–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keusch GT. Shigella infections. Clin Gastroenterol. 1979;8:645–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taneja N, Mewara A. Shigellosis: epidemiology in India. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143:565–576. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.187104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parajuli P, Adamski M, Verma NK. Bacteriophages are the major drivers of Shigella flexneri serotype 1c genome plasticity: a complete genome analysis. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:722. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreccio C, Prado V, Ojeda A, Cayyazo M, Abrego P, Guers L, et al. Epidemiologic patterns of acute diarrhea and endemic Shigella infections in children in a poor periurban setting in Santiago, Chile. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:614–627. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Seidlein L, Kim DR, Ali M, Lee H, Wang X, Thiem VD, et al. A multicentre study of Shigella diarrhoea in six Asian countries: disease burden, clinical manifestations, and microbiology. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuesch-Inderbinen M, Heini N, Zurfluh K, Althaus D, Hachler H, Stephan R. Shigella antimicrobial drug resistance mechanisms, 2004–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1083–1085. doi: 10.3201/eid2206.152088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Z, Zhou X, Li B, Wang S, Cheng F, Zhang J. Genomic analysis and resistance mechanisms in Shigella flexneri 2a strain 301. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24:323–336. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei J, Goldberg MB, Burland V, Venkatesan MM, Deng W, Fournier G, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomics of Shigella flexneri serotype 2a strain 2457T. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2775–2786. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2775-2786.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desler C, Suravajhala P, Sanderhoff M, Rasmussen M, Rasmussen LJ. In silico screening for functional candidates amongst hypothetical proteins. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loewenstein Y, Raimondo D, Redfern OC, Watson J, Frishman D, Linial M, et al. Protein function annotation by homology-based inference. Genome Biol. 2009;10:207. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-2-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nimrod G, Schushan M, Steinberg DM, Ben-Tal N. Detection of functionally important regions in “hypothetical proteins” of known structure. Structure. 2008;16:1755–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar K, Prakash A, Tasleem M, Islam A, Ahmad F, Hassan MI. Functional annotation of putative hypothetical proteins from Candida dubliniensis . Gene. 2014;543:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lubec G, Afjehi-Sadat L, Yang JW, John JP. Searching for hypothetical proteins: theory and practice based upon original data and literature. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:90–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahbaaz M, Ahmad F, Imtaiyaz Hassan M. Structure-based functional annotation of putative conserved proteins having lyase activity from Haemophilus influenzae . 3 Biotech. 2015;5:317–336. doi: 10.1007/s13205-014-0231-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha A, Ahmad F, Hassan MI. Structure based functional annotation of putative conserved proteins from Treponema pallidum: search for a potential drug target. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2015;12:46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams MA, Suits MD, Zheng J, Jia Z. Piecing together the structure-function puzzle: experiences in structure-based functional annotation of hypothetical proteins. Proteomics. 2007;7:2920–2932. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doerks T, von Mering C, Bork P. Functional clues for hypothetical proteins based on genomic context analysis in prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6321–6326. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazi MA, Kibria MG, Mahfuz M, Islam MR, Ghosh P, Afsar MN, et al. Functional, structural and epitopic prediction of hypothetical proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: an in silico approach for prioritizing the targets. Gene. 2016;591:442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8:283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anandakumar S, Shanmughavel P. Computational annotation for hypothetical proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Comput Sci Syst Biol. 2008;1:50–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. ‘Conserved hypothetical’ proteins: prioritization of targets for experimental study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5452–5463. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chothia C, Lesk AM. The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J. 1986;5:823–826. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eddy SR. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, et al. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D237–D240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bateman A, Birney E, Cerruti L, Durbin R, Etwiller L, Eddy SR, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:276–280. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finn RD, Clements J, Arndt W, Miller BL, Wheeler TJ, Schreiber F, et al. HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W30–W38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D302–D305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Castro E, Sigrist CJ, Gattiker A, Bulliard V, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Gasteiger E, et al. ScanProsite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W362–W365. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanmugham B, Pan A. Identification and characterization of potential therapeutic candidates in emerging human pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus: a novel hierarchical in silico approach. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu CS, Chen YC, Lu CH, Hwang JK. Prediction of protein sub-cellular localization. Proteins. 2006;64:643–651. doi: 10.1002/prot.21018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu NY, Wagner JR, Laird MR, Melli G, Rey S, Lo R, et al. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1608–1615. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhasin M, Garg A, Raghava GP. PSLpred: prediction of subcellular localization of bacterial proteins. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2522–2524. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirokawa T, Boon-Chieng S, Mitaku S. SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:378–379. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tusnady GE, Simon I. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:849–850. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bendtsen JD, Kiemer L, Fausboll A, Brunak S. Non-classical protein secretion in bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Nakaya A. The KEGG databases at GenomeNet. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:42–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–W120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sillitoe I, Cuff AL, Dessailly BH, Dawson NL, Furnham N, Lee D, et al. New functional families (FunFams) in CATH to improve the mapping of conserved functional sites to 3D structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D490–D498. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gough J, Karplus K, Hughey R, Chothia C. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of hidden Markov models that represent all proteins of known structure. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:903–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rappoport N, Karsenty S, Stern A, Linial N, Linial M. ProtoNet 6.0: organizing 10 million protein sequences in a compact hierarchical family tree. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D313–D320. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu D, Xu Y, Uberbacher EC. Computational tools for protein modeling. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2000;1:1–21. doi: 10.2174/1389203003381469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen CC, Hwang JK, Yang JM. (PS)2-v2: template-based protein structure prediction server. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen HB, Chou KC. Predicting protein fold pattern with functional domain and sequential evolution information. J Theor Biol. 2009;256:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baron C, Coombes B. Targeting bacterial secretion systems: benefits of disarmament in the microcosm. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:19–27. doi: 10.2174/187152607780090685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saha S, Raghava GP. VICMpred: an SVM-based method for the prediction of functional proteins of Gram-negative bacteria using amino acid patterns and composition. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2006;4:42–47. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(06)60015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garg A, Gupta D. VirulentPred: a SVM based prediction method for virulent proteins in bacterial pathogens. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, et al. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eng J. ROC analysis: web-based calculator for ROC curves. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 2006. [Accessed 2018 Sep 1]. Available from: http://www.jrocfit.org. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shahbaaz M, Hassan MI, Ahmad F. Functional annotation of conserved hypothetical proteins from Haemophilus influenzae Rd KW20. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delucia AM, Six DA, Caughlan RE, Gee P, Hunt I, Lam JS, et al. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) inner-core phosphates are required for complete LPS synthesis and transport to the outer membrane in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. MBio. 2011;2:e00142–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00142-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burk DL, Ghuman N, Wybenga-Groot LE, Berghuis AM. X-ray structure of the AAC(6′)-Ii antibiotic resistance enzyme at 1.8 A resolution: examination of oligomeric arrangements in GNAT superfamily members. Protein Sci. 2003;12:426–437. doi: 10.1110/ps.0233503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bjornson HS. Enzymes associated with the survival and virulence of gram-negative anaerobes. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6(Suppl 1):S21–S24. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.supplement_1.s21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morishita R, Kawagoshi A, Sawasaki T, Madin K, Ogasawara T, Oka T, et al. Ribonuclease activity of rat liver perchloric acid-soluble protein, a potent inhibitor of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20688–20692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lambrecht JA, Flynn JM, Downs DM. Conserved YjgF protein family deaminates reactive enamine/imine intermediates of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme reactions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3454–3461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmitz G, Downs DM. Reduced transaminase B (IlvE) activity caused by the lack of yjgF is dependent on the status of threonine deaminase (IlvA) in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:803–810. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.803-810.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aravind L, Leipe DD, Koonin EV. Toprim: a conserved catalytic domain in type IA and II topoisomerases, DnaG-type primases, OLD family nucleases and RecR proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4205–4213. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fry J, Wood M, Poole PS. Investigation of myo-inositol catabolism in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae and its effect on nodulation competitiveness. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14:1016–1025. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.8.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bollinger JM, Jr, Kwon DS, Huisman GW, Kolter R, Walsh CT. Glutathionylspermidine metabolism in Escherichia coli: purification, cloning, overproduction, and characterization of a bi-functional glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14031–14041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.14031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ejim LJ, D’Costa VM, Elowe NH, Loredo-Osti JC, Malo D, Wright GD. Cystathionine beta-lyase is important for virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3310–3314. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3310-3314.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gerdes K, Wagner EG. RNA antitoxins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawano M, Aravind L, Storz G. An antisense RNA controls synthesis of an SOS-induced toxin evolved from an antitoxin. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:738–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawano M. Divergently overlapping cis-encoded antisense RNA regulating toxin-antitoxin systems from E. coli: hok/sok, ldr/rdl, symE/symR. RNA Biol. 2012;9:1520–1527. doi: 10.4161/rna.22757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruggeri ZM, Ware J. von Willebrand factor. FASEB J. 1993;7:308–316. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.2.8440408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ahmad F, Jan R, Kannan M, Obser T, Hassan MI, Oyen F, et al. Characterisation of mutations and molecular studies of type 2 von Willebrand disease. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109:39–46. doi: 10.1160/TH12-07-0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naqvi AA, Shahbaaz M, Ahmad F, Hassan MI. Identification of functional candidates amongst hypothetical proteins of Treponema pallidum ssp. pallidum . PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Colombatti A, Bonaldo P, Doliana R. Type A modules: interacting domains found in several non-fibrillar collagens and in other extracellular matrix proteins. Matrix. 1993;13:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tavernarakis N, Driscoll M, Kyrpides NC. The SPFH domain: implicated in regulating targeted protein turnover in stomatins and other membrane-associated proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:425–427. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01467-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gehl B, Sweetlove LJ. Mitochondrial Band-7 family proteins: scaffolds for respiratory chain assembly? Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:141. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu T, McCandlish AC, Gronenberg LS, Chng SS, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. Identification of a protein complex that assembles lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11754–11759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604744103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cerveny L, Straskova A, Dankova V, Hartlova A, Ceckova M, Staud F, et al. Tetratricopeptide repeat motifs in the world of bacterial pathogens: role in virulence mechanisms. Infect Immun. 2013;81:629–635. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01035-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singer HM, Kuhne C, Deditius JA, Hughes KT, Erhardt M. The Salmonella Spi1 virulence regulatory protein HilD directly activates transcription of the flagellar master operon flhDC. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:1448–1457. doi: 10.1128/JB.01438-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kowalski JC, Belfort M, Stapleton MA, Holpert M, Dansereau JT, Pietrokovski S, et al. Configuration of the catalytic GIY-YIG domain of intron endonuclease I-TevI: coincidence of computational and molecular findings. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2115–2125. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.10.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Roey P, Meehan L, Kowalski JC, Belfort M, Derbyshire V. Catalytic domain structure and hypothesis for function of GIY-YIG intron endonuclease I-TevI. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:806–811. doi: 10.1038/nsb853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iyer LM, Zhang D, Rogozin IB, Aravind L. Evolution of the deaminase fold and multiple origins of eukaryotic editing and mutagenic nucleic acid deaminases from bacterial toxin systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9473–9497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shu W, Liu J, Ji H, Lu M. Core structure of the outer membrane lipoprotein from Escherichia coli at 1.9 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1101–1112. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rothberg JM, Jacobs JR, Goodman CS, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. slit: an extracellular protein necessary for development of midline glia and commissural axon pathways contains both EGF and LRR domains. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2169–2187. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kovacs-Simon A, Titball RW, Michell SL. Lipoproteins of bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun. 2011;79:548–561. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00682-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Torti SV, Park JT. Lipoprotein of gram-negative bacteria is essential for growth and division. Nature. 1976;263:323–326. doi: 10.1038/263323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saurin W, Hofnung M, Dassa E. Getting in or out: early segregation between importers and exporters in the evolution of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:22–41. doi: 10.1007/pl00006442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Freeman ZN, Dorus S, Waterfield NR. The KdpD/KdpE two-component system: integrating K(+) homeostasis and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ibanez-Ruiz M, Robbe-Saule V, Hermant D, Labrude S, Norel F. Identification of RpoS (sigma(S))-regulated genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5749–5756. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.20.5749-5756.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Peterson PA, Rask L, Ostberg L, Andersson L, Kamwendo F, Pertoft H. Studies on the transport and cellular distribution of vitamin A in normal and vitamin A-deficient rats with special reference to the vitamin A-binding plasma protein. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:4009–4022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Minailiuc OM, Vavelyuk O, Gandhi S, Hung MN, Cygler M, Ekiel I. NMR structure of YcgL, a conserved protein from Escherichia coli representing the DUF709 family, with a novel alpha/beta/alpha sandwich fold. Proteins. 2007;66:1004–1007. doi: 10.1002/prot.21198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Livorsi DJ, Stenehjem E, Stephens DS. Virulence factors of gram-negative bacteria in sepsis with a focus on Neisseria meningitidis. In: Herwald H, Egesten A, editors. Sepsis: Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Responses. Basel: Karger Publishers; 2011. pp. 31–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marra A. Targeting virulence for antibacterial chemotherapy: identifying and characterising virulence factors for lead discovery. Drugs R D. 2006;7:1–16. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200607010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.