Abstract

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MS) in the nonobese population is not low. However, the identification and risk mitigation of MS are not easy in this population. We aimed to develop an MS prediction model using genetic and clinical factors of nonobese Koreans through machine learning methods. A prediction model for MS was designed for a nonobese population using clinical and genetic polymorphism information with five machine learning algorithms, including naïve Bayes classification (NB). The analysis was performed in two stages (training and test sets). Model A was designed with only clinical information (age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and exercise status), and for model B, genetic information (for 10 polymorphisms) was added to model A. Of the 7,502 nonobese participants, 647 (8.6%) had MS. In the test set analysis, for the maximum sensitivity criterion, NB showed the highest sensitivity: 0.38 for model A and 0.42 for model B. The specificity of NB was 0.79 for model A and 0.80 for model B. In a comparison of the performances of models A and B by NB, model B (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC] = 0.69, clinical and genetic information input) showed better performance than model A (AUC = 0.65, clinical information only input). We designed a prediction model for MS in a nonobese population using clinical and genetic information. With this model, we might convince nonobese MS individuals to undergo health checks and adopt behaviors associated with a preventive lifestyle.

Keywords: genetic polymorphism, machine learning, metabolic syndrome

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome refers to a state in which multiple diseases, such as hyperglycemia, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity, occur together in one individual [1]. Complications of metabolic syndrome may increase the incidence of cardiovascular diseases [2], and obstructive sleep apnea [3] or fatty liver disease [4] may also occur. It is known that the occurrence or prognosis of colorectal cancer [5], breast cancer [6], endometrial cancer [7, 8], and prostate cancer [9] is closely related to the constituents of metabolic syndrome [10]. Therefore, predicting the group at high risk for metabolic syndrome and actively preventing metabolic syndrome are essential for health care. The most common cause of metabolic syndrome has been presumed to be abdominal obesity [11]. In recent years, however, the need to consider nonobese metabolic syndrome has received attention [12]. Unlike obese metabolic syndrome, for which body weight reductions can decrease the risk and which has received much attention in health care, nonobese metabolic syndrome has no common cause, such as obesity. Without a special test, it is impossible to detect or suspect metabolic syndrome in nonobese individuals. In the nonobese metabolic syndrome population, the perception of health risks is relatively low and may be a blind spot of health care. Genetic studies of metabolic syndrome have reported a number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [13–20] that are known to be closely related to clinical factors, such as aging [21], sex [22], abdominal obesity [11], physical activity [23], alcohol consumption [24], and smoking [25]. However, no model has been published that combines these clinical and genetic factors in a metabolic syndrome prediction model. In this study, we constructed a model to predict metabolic syndrome in nonobese people using machine learning algorithms with factors such as age, sex, environmental factors, and lifestyle habits as well as genetic predisposition factors, such as SNPs, and evaluated the performance of the model.

Methods

Study population

We retrospectively used the Gene-Environmental Interaction and Phenotype (GENIE) database for Koreans; these data were collected from 10,349 healthy individuals who visited Seoul National University Hospital Gangnam Center for a comprehensive health check-up and consented to have their specimens included in a biospecimen repository. The program for comprehensive health check-ups and the GENIE database is described in another paper [26]. Briefly, blood pressure, waist circumference, height, and weight information were collected through anthropometric measurements during a health screening, and information on age, smoking, alcohol, exercise, and drug use was collected through interviews. After at least 10 hours of fasting, peripheral blood samples were obtained from all patients to determine the levels of fasting glucose, triglycerides, high-density lipopolysaccharide (HDL) cholesterol, and DNA samples were collected from the remaining blood. SNP genotyping was performed by an Affymetrix Axiom KORV1.1-96 Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at DNA Link Inc. (Seoul, Korea).

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital approved this study protocol (IRB number H-1807-030-955), and informed consent was waived by the board. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical assessment and definitions

For this study, metabolic syndrome is defined according to the International Diabetes Federation’s criteria for the South Asian ethnic group [27], that is, the presence of at least 3 of the following metabolic risk factors: increased waist circumference (males ≥ 90 cm; females ≥ 80 cm); elevated blood pressure (≥130/85 mm Hg or the use of medications for hypertension); elevated fasting glucose levels (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or the use of medications for hyperglycemia); elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dL); and reduced HDL cholesterol levels (males < 40 mg/dL, females < 50 mg/dL) or being under treatment for dyslipidemia. The metabolic score is the sum of the number of metabolic risk factors. Alcohol consumption was defined as yes when more than 140 g of alcohol was consumed per week, and smoking status was categorized as no or ex-smokers vs. current smoker. Exercise was grouped as not active vs. physically active. Physically active was defined as performing at least 150 minutes of vigorous or moderate intensity active per week. The study was conducted in nonobese individuals whose body mass index (BMI) was less than 25 kg/m2.

Genotyping and quality control

Genomic DNA was separated from venous blood samples, and 200 ng was genotyped using a Hybridization on Affymetrix Axiom KORV1.0-96 Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The PLINK program version 1.9 (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2) was used for the quality control process for the raw genotype data, resulting in a total of 586,730 SNPs to be used. SNPs with case and control minor allele frequencies less than 1%, case or control call rates less than 95% or a significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the controls (p < 0.0001) were excluded.

SNP selection for analysis

To design a model for predicting metabolic syndrome in the nonobese population, we selected the SNPs in two ways. In the first way, we used the genome-wide association study (GWAS) catalog database. We extracted the SNP list from the GWAS Catalog with keywords such as “metabolic syndrome,” “obesity,” and “adipose tissue.” For the extracted SNPs, we used SNPs that were included among the SNPs of the Affymetrix Axiom KORV1.0-96 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and had a p-value of less than 0.01 in the case control study for metabolic syndrome in our nonobese population. In the second way, we performed a GWAS study for metabolic syndrome in our nonobese population and selected the SNPs with p-values that passed the Bonferroni-corrected threshold (p < 8.52 × 10−8). We included all the SNPs selected using both ways to design the algorithm.

Prediction model design by machine learning tools

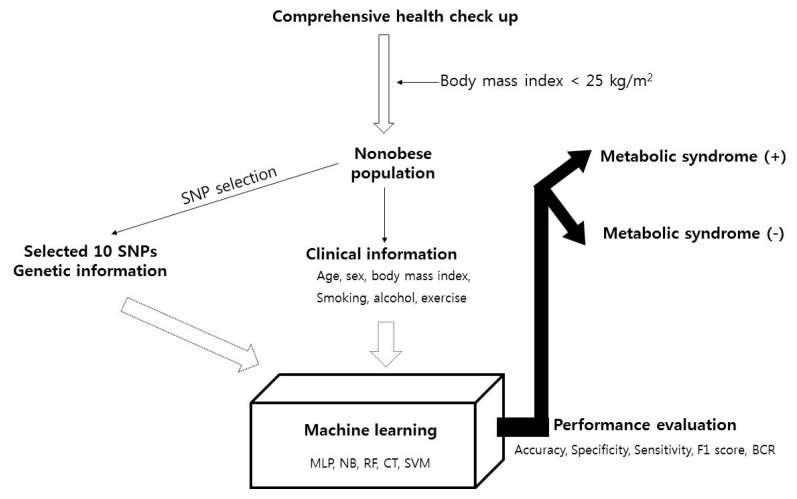

For the nonobese population (BMI < 25 kg/m2) population, the clinical information (age, sex, BMI, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, and exercise) and SNPs selected as described above (finally, 10 SNPs were selected: rs3764261, rs247617, rs2266788, rs964184, rs10830963, rs1260326, rs10830962, rs1883025, rs1919128, and rs11757661) were used to perform five types of machine learning analysis, multilayer perceptron (MLP) [28], naïve Bayes classification (NB) [29], random forest classification (RF) [30], decision trees classification (J48) [31], and support vector machine classification (SVM) [32], to predict metabolic syndrome. The additive model was used for genotype data used. The total population was divided into sets in a 7:3 ratio for the training set, which was used to develop the model, relative to the test set, which was used to validate the resulting model. The performance of the model was evaluated according to accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, F1 score, and the balanced classification rate. Model A was designed with only clinical information, and model B also included genetic information (information about the 10 SNPs). The machine learning analysis was conducted by Weka (Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis; University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand). All analyses were two-tailed, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were performed using PLINK version 1.9 (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2), R statistical software (version 3.4.4) was used for statistical analyses, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The study outline is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flow pipeline. SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; MLP, multilayer perceptron; NB, naïve Bayes classification; RF, random forest classification; CT, decision tree classification; SVM, support vector machine classification; BCR, balanced classification rate.

Statistical analysis

For the GWAS, logistic regression analyses were used, controlling for sex as a covariate in the additive model. The performance was compared between model A (clinical data input only) and model B (clinical data + genetic data input) by drawing the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and comparing the area under the curve confusion matrix. Statistical tests were performed using PLINK version 1.9 (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2), SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study population characteristics

The 10,349 participants included 7,502 nonobese individuals. Metabolic syndrome was observed in 647 (8.6%) persons. The nonobese individuals were grouped into a training set (n = 5,251) and a test set (n = 2,251), and the baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and exercise status information were input into model A, and SNP information was additionally input into model B. The SNP information is described in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic features of the training and test set populations

| Training set (n = 5,251) | Test set (n = 2,251) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 49.3 ± 10.5 | 52.1 ± 9.9 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 2,078 (39.6) | 1,676 (74.5) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | 20.9 ± 1.7 | 24.0 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 76.7 ± 6.1 | 85.6 ± 4.1 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 85.3 ± 49.4 | 118.7 ± 70.8 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 57.5 ± 12.5 | 51.1 ± 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose level (mg/dL) | 94.5 ± 14.3 | 100.4 ± 16.0 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 111.6 ± 12.7 | 117.6 ± 12.5 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 72.8 ± 9.7 | 78.0 ± 9.4 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (current smoker) | 1,581 (30.1) | 1,202 (53.4) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption ≥ 140 g/wk | 708 (13.5) | 613 (27.2) | <0.001 |

| Exercise (physically active) | 263 (5.0) | 144 (6.4) | 0.017 |

| Metabolic syndrome present | 223 (4.2) | 424 (18.8) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

HDL, high-density lipopolysaccharide.

Table 2.

Information on the SNPs used in the algorithm

| Chromosome number | Position | Overlapped gene | Representative trait of association | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3764261 | chr16 | 56959412 | CETP | Metabolic syndrome [13], triglyceride, HDL cholesterol levels [14] |

| rs247617 | chr16 | 56956804 | CETP | Metabolic syndrome [15], HDL [16] |

| rs2266788 | chr11 | 116789970 | APOA5 | Metabolic syndrome [13], triglyceride, HDL cholesterol levels [15] |

| rs964184 | chr11 | 116778201 | ZPR1 | Metabolic syndrome [17], triglyceride, HDL cholesterol levels [18] |

| rs10830963 | chr11 | 92975544 | MTNR1B | Obesity-related traits [19] |

| rs1260326 | chr2 | 27508073 | GCKR | Metabolic traits [15] |

| rs10830962 | chr11 | 92965261 | MTNR1B | Metabolic syndrome [15] |

| rs1883025 | chr9 | 104902020 | ABCA1 | Metabolic syndrome [14], HDL cholesterol levels [24] |

| rs1919128 | chr2 | 27578892 | C2orf16 | Metabolic syndrome [13] |

| rs11757661 | chr6 | 88473861 | RNGTT | Adipose tissue [20] |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; HDL, high-density lipopolysaccharide.

Overall comparison of the various machine learning tools

We used six machine learning methods, namely, MLP, NB, RF, decision tree classification, and SVM. Table 3 summarizes the performance of each model obtained with the various machine learning tools in the training and test sets. The purpose of generating our models is to provide a warning for a nonobese person who has an increased risk for metabolic syndrome. Therefore, we evaluated the sensitivity of the designed model. NB showed the best sensitivity, 0.38 for model A and 0.42 for model B. The specificity of NB was 0.79 for model A and 0.80 for model B.

Table 3.

Performance comparison among respective machine learning algorithms for predicting metabolic syndrome presence

| Training set | Test set | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| AC | SP | SN | F1 | BCR | AC | SP | SN | F1 | BCR | |

| MLP | ||||||||||

| Model A | 95.75 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 81.16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Model B | 97.81 | 0.99 | 0.515 | 0.672 | 0.717 | 78.90 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 0.167 | 0.333 |

|

| ||||||||||

| NB | ||||||||||

| Model A | 94.24 | 0.98 | 0.12 | 0.147 | 0.337 | 71.43 | 0.79 | 0.38 | 0.334 | 0.289 |

| Model B | 94.44 | 0.98 | 0.13 | 0.167 | 0.351 | 73.24 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 0.360 | 0.327 |

|

| ||||||||||

| RF | ||||||||||

| Model A | 98.78 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.832 | 0.844 | 78.80 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.122 | 0.272 |

| Model B | 99.71 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.966 | 0.967 | 82.14 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.014 | 0.083 |

|

| ||||||||||

| CT | ||||||||||

| Model A | 95.75 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 81.16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Model B | 95.66 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 82.20 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||||||

| SVM | ||||||||||

| Model Aa | 95.75 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 81.16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Model Bb | 95.66 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 82.20 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

AC, accuracy; SP, specificity; SN, sensitivity; F1, F1 score; BCR, balanced classification rate; MLP, multilayer perceptron; NB, Naïve Bayes classification; RF, random forest classification; CT, decision tree classification; SVM, support vector machine classification; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Attributes for each model.

Model A: age, sex, body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise

Model B: Model A + rs3764261, rs247617, rs2266788, rs964184, rs10830963, rs1260326, rs10830962, rs1883025, rs1919128, rs11757661 SNPs.

Performance comparison between model A and model B

Via the area under the ROC curve (AUC), we compared the performance of model A and model B obtained with NB. Model B (AUC = 0.69), for which the input factors were the SNP information in addition to the factors used in model A, showed better performance than model A (AUC = 0.65), for which the input factors were age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and exercise status.

Discussion

This study designed a predictive model for metabolic syndrome in nonobese people through machine learning using clinical information and polymorphism information obtained at a health screening. Among the various machine learning methods, NB showed the best performance, and the prediction model that included genetic information showed better performance than the prediction model designed with only clinical data.

It has been reported that people with metabolic syndrome have a 5-fold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, a 3-fold increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease [1], and increased cancer risk and cancer-related mortality [5–9].

Therefore, predicting the population with a high risk for metabolic syndrome and actively intervening with these individuals are very important for promoting health. Obesity is the most common risk factor for metabolic syndrome. Obesity is known to be associated with complications such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease [33, 34]. Obesity is clinically evident, so obese people can recognize the risk and prevent metabolic syndrome from occurring by undergoing aggressive weight loss efforts. However, metabolic disturbance can also occur in nonobese people. One cohort study reported that reduced inflammatory status, which is a metabolic syndrome pathogenesis, is observed in nonobese patients as well as obese patients [35, 36]. The problem for these nonobese patients is that without a specific biochemical test, these individuals do not know if they have developed metabolic syndrome and that they do not know if they are at risk for metabolic syndrome. The prevalence of undiagnosed metabolic syndrome in people with normal BMI is reported to be 5.2%–8.9% [37]. Therefore, predicting these factors plays a very important role in health care. To increase the predictive power in this group, we made a prediction model including genetic factors as well as clinical factors and performed analysis through various kinds of machine learning. Naïve Bayes classification showed the best performance.

The naïve Bayesian classifier (NBC) is a powerful probabilistic model that has been applied in various medical studies [38, 39]. The superiority of the NBC is that it takes all information into account to reach a decision, which is natural way for physicians to make diagnostic and prognostic decisions [40].

This study has the following limitations. First, only Korean individuals were included. Therefore, for generalization to other ethnicities, it is necessary to expand the study to include other ethnicities as well. Second, although the naïve Bayesian algorithm has the best performance, its sensitivity of 0.42 is not sufficient.

In future studies, it is necessary to improve performance by applying a deep learning algorithm.

The superiority of this study is as follows. First, we constructed a prediction model by integrating clinical information, environmental factors, and genetic information. Genetic studies of metabolic syndrome have been reported mostly for SNPs and are clinically known to be caused by several environmental factors. However, no method or algorithms have been published for integrating big data information, which is the result of these individual studies, into a metabolic syndrome prediction model for nonobese populations. In metabolic syndrome, not only the genetic polymorphism of SNPs but also factors such as age, sex, environmental factors, and lifestyle habits are all involved, and the presence of these genetic and clinical factors controls the development of metabolic syndrome. In addition, although the GWASs used in the existing SNP analysis found SNPs that are candidate markers for a number of metabolic disorders, all of the studies considered individual SNPs, and no studies have analyzed SNPs in an integrated manner. Second, machine learning was used to build predictive models. The traditional construction of models by statistical methods is mostly conducted with only clinical information, and factors in the prediction model that have borderline influence are often deleted during the model design process. Additionally, for the traditional models, it is difficult to reflect all the associations between the factors. In the case of machine learning, data and factors of borderline significance can be considered in the analysis without overlooking data that are not well known. Third, model A in our study, which is designed only using clinical information, itself has useful value in the clinical field. Model A used information such as age, sex, body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, and exercise. This information can be obtained easily without any special medical inspection. If a nonobese person inputs their information into the algorithms, they can be alerted to their risk of metabolic syndrome and take active interventions to prevent complications. This application can be performed by the nonobsese person himself or herself without the help of a medical specialist. After conducting a replication study in another population set and improving the performance of this model, we are planning to make it accessible as a website in the future.

In this study, a prediction model was constructed by integrating clinical information, environmental factors, and genetic information. The purpose of this study is to provide a prediction model for metabolic syndrome that is more predictive of metabolic syndrome than previous models, by using clinical and genetic markers related to metabolic syndrome specifically in a nonobese population. Using this prediction model, we could predict the group of nonobese individuals who have a high risk of developing metabolic syndrome. For the individuals in this group who previously did not feel a need to use healthcare services and were not concerned about metabolic syndrome, we could encourage them to receive health checks and modify their lifestyle to include preventive habits. This process would save them from cardiovascular disease and several cancers that are complications of metabolic syndrome. This can be used as part of a more comprehensive health care method.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (10050154, Business Model Development for Personalized Medicine Based on Integrated Genome and Clinical Information) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MI, Korea).

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution:

Conceptualization: SHC, EKC, HR, ES, JEL

Data curation: EKC, SWO

Formal analysis: EKC, ES, SL

Methodology: EKC, ES, SL

Software: ES, SL, JEL

Investigation: SHC, EKC, HR, SWO

Writing – original draft preparation: EKC

Writing – review and editing: SHC, SWO

Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.O’Neill S, O’Driscoll L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev. 2015;16:1–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Metabolic syndrome: from the genetics to the pathophysiology. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:149–157. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drager LF, Togeiro SM, Polotsky VY, Lorenzi-Filho G. Obstructive sleep apnea: a cardiometabolic risk in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yki-Jarvinen H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:901–910. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Capuano A, Bellastella G, Maiorino MI, Rafaniello C, et al. Colorectal cancer association with metabolic syndrome and its components: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2013;44:634–647. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9939-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Argolo DF, Hudis CA, Iyengar NM. The impact of obesity on breast cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018;20:47. doi: 10.1007/s11912-018-0688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni J, Zhu T, Zhao L, Che F, Chen Y, Shou H, et al. Metabolic syndrome is an independent prognostic factor for endometrial adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:835–839. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Capuano A, Bellastella G, Maiorino MI, Giugliano D. Metabolic syndrome and endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2014;45:28–36. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gacci M, Russo GI, De Nunzio C, Sebastianelli A, Salvi M, Vignozzi L, et al. Meta-analysis of metabolic syndrome and prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20:146–155. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2017.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendonca FM, de Sousa FR, Barbosa AL, Martins SC, Araujo RL, Soares R, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer: which link? Metabolism. 2015;64:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eftekharzadeh A, Asghari G, Serahati S, Hosseinpanah F, Azizi A, Barzin M, et al. Predictors of incident obesity phenotype in nonobese healthy adults. Eur J Clin Invest. 2017;47:357–365. doi: 10.1111/eci.12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraja AT, Vaidya D, Pankow JS, Goodarzi MO, Assimes TL, Kullo IJ, et al. A bivariate genome-wide approach to metabolic syndrome: STAMPEED consortium. Diabetes. 2011;60:1329–1339. doi: 10.2337/db10-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spracklen CN, Chen P, Kim YJ, Wang X, Cai H, Li S, et al. Association analyses of East Asian individuals and trans-ancestry analyses with European individuals reveal new loci associated with cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:1770–1784. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristiansson K, Perola M, Tikkanen E, Kettunen J, Surakka I, Havulinna AS, et al. Genome-wide screen for metabolic syndrome susceptibility Loci reveals strong lipid gene contribution but no evidence for common genetic basis for clustering of metabolic syndrome traits. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:242–249. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coram MA, Duan Q, Hoffmann TJ, Thornton T, Knowles JW, Johnson NA, et al. Genome-wide characterization of shared and distinct genetic components that influence blood lipid levels in ethnically diverse human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:904–916. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surakka I, Horikoshi M, Magi R, Sarin AP, Mahajan A, Lagou V, et al. The impact of low-frequency and rare variants on lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2015;47:589–597. doi: 10.1038/ng.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comuzzie AG, Cole SA, Laston SL, Voruganti VS, Haack K, Gibbs RA, et al. Novel genetic loci identified for the patho-physiology of childhood obesity in the Hispanic population. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabatti C, Service SK, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, Ripatti S, Brodsky J, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of metabolic traits in a birth cohort from a founder population. Nat Genet. 2009;41:35–46. doi: 10.1038/ng.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox CS, Liu Y, White CC, Feitosa M, Smith AV, Heard-Costa N, et al. Genome-wide association for abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipose reveals a novel locus for visceral fat in women. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guarner V, Rubio-Ruiz ME. Low-grade systemic inflammation connects aging, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2015;40:99–106. doi: 10.1159/000364934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rochlani Y, Pothineni NV, Mehta JL. Metabolic syndrome: does it differ between women and men? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2015;29:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s10557-015-6593-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos D, Weinem M, Stefanadis C. Diet, exercise and the metabolic syndrome. Rev Diabet Stud. 2006;3:118–126. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2006.3.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun K, Ren M, Liu D, Wang C, Yang C, Yan L. Alcohol consumption and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin HS, Oh JE, Cho YJ. The association between smoking cessation period and metabolic syndrome in Korean men. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2018;30:415–424. doi: 10.1177/1010539518786517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee C, Choe EK, Choi JM, Hwang Y, Lee Y, Park B, et al. Health and Prevention Enhancement (H-PEACE): a retrospective, population-based cohort study conducted at the Seoul National University Hospital Gangnam Center, Korea. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019327. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J, IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group The metabolic syndrome: a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tafeit E, Reibnegger G. Artificial neural networks in laboratory medicine and medical outcome prediction. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:845–853. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdo A, Chen B, Mueller C, Salim N, Willett P. Ligand-based virtual screening using Bayesian networks. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:1012–1020. doi: 10.1021/ci100090p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plewczynski D, von Grotthuss M, Rychlewski L, Ginalski K. Virtual high throughput screening using combined random forest and flexible docking. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2009;12:484–489. doi: 10.2174/138620709788489000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Che D, Hockenbury C, Marmelstein R, Rasheed K. Classification of genomic islands using decision trees and their ensemble algorithms. BMC Genomics. 2010;11( Suppl 2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorissen RN, Gilson MK. Virtual screening of molecular databases using a support vector machine. J Chem Inf Model. 2005;45:549–561. doi: 10.1021/ci049641u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malnick SD, Knobler H. The medical complications of obesity. QJM. 2006;99:565–579. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen DM, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pajunen P, Kotronen A, Korpi-Hyovalti E, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Oksa H, Niskanen L, et al. Metabolically healthy and unhealthy obesity phenotypes in the general population: the FIN-D2D Survey. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:754. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips CM, Perry IJ. Does inflammation determine metabolic health status in obese and nonobese adults? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1610–E1619. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bo S, Ciccone G, Pearce N, Merletti F, Gentile L, Cassader M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed metabolic syndrome in a population of adult asymptomatic subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:362–365. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanco R, Inza I, Merino M, Quiroga J, Larranaga P. Feature selection in Bayesian classifiers for the prognosis of survival of cirrhotic patients treated with TIPS. J Biomed Inform. 2005;38:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandberg R, Winberg G, Branden CI, Kaske A, Ernberg I, Coster J. Capturing whole-genome characteristics in short sequences using a naive Bayesian classifier. Genome Res. 2001;11:1404–1409. doi: 10.1101/gr.186401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zelic I, Kononenko I, Lavrac N, Vuga V. Induction of decision trees and Bayesian classification applied to diagnosis of sport injuries. J Med Syst. 1997;21:429–444. doi: 10.1023/a:1022880431298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]