Abstract

We examined the proportion and correlates of loss to follow-up (LTFU) among female entertainment and sex workers (FESWs) in a longitudinal HIV prevention intervention trial in Cambodia. The Cambodia Integrated HIV and Drug Prevention Intervention trial tested a comprehensive package of interventions aimed at reducing amphetamine-type stimulant use and HIV risk among FESWs in ten provinces. The present study estimated the proportion of women LTFU and assessed factors associated with LTFU. Logistic regression analyses were used. Of a total 596 women enrolled, the cumulative proportion of LTFU was 29.5% (n = 176) between zero- and 12-month follow-up. In multivariate analyses, women with no living children (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1, 2.3) and those who experienced recent food insecurity (AOR 1.7; 95%CI: 1.1, 2.7) were more likely to be LTFU. Women who were members of the SMARTgirl HIV prevention programme for > 6 months compared to non-members were less likely to be LTFU (AOR 0.3; 95%CI: 0.2, 0.6). LTFU was moderately high in this study and similar to other studies, indicating a need for strategies to retain this population in HIV prevention programmes and research. Interventions aimed at stabilizing women’s lives, including reducing food insecurity and creating communities of engagement for FESWs, should be considered.

Keywords: Female entertainment worker, sex workers, HIV prevention, loss to follow-up, intervention, Cambodia

Introduction

Women engaged in transactional sex remain one of the most at-risk groups for HIV globally.1 A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies from 50 low- and middle-income countries showed that pooled HIV prevalence in this population was as high as 11.8%, 13.5 times greater than in the general population of women of childbearing age.1 In Cambodia, women engaged in transactional sex are a heterogeneous group who work in a variety of settings, including entertainment establishments (karaoke bars, massage parlours, beer gardens, cafes, and barber shops), guest houses, streets, and parks. We use the term female entertainment and sex workers (FESWs) to describe this group.2 In 2016, national surveillance data estimated an HIV prevalence of 3.2% among Cambodian FESWs,3 five-fold higher than in the general population.4 Research by our group has also shown that FESWs who use amphetamine-type stimulants (ATSs) have more sexual partners, are more likely to engage in condomless sex, are at higher risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs),5,6 and to be less engaged in preventive care.7

Prospective longitudinal studies, including intervention trials, aim to minimize loss to follow-up (LTFU) to reduce bias and maximize study validity.8–10 While LTFU may be defined differently from one study to another, non-random loss occurs when losses are related to the study exposure or outcome and have potential to be damaging to study validity.8–11 Often, LTFU cannot be managed by statistical control.8–11

Assessing factors associated with retention and loss can help to inform study procedures and reduce the potential for compromising study validity. Further, identifying and understanding the predictors of LTFU within longitudinal cohorts can inform programme planning when implementing interventions that are suited to a population of interest. Three prospective studies conducted among Cambodian FESWs reported high rates of LTFU. One study assessing HIV and STI incidence in a prospective cohort closed 12 months after initiation, citing concerns about insufficient sample size resulting from 51% LTFU.12 Two consecutive cohort studies, each conducted for one year, among FESWs in Phnom Penh between 2007 and 2010 by our group reported LTFU of 37 and 23% at 12 months, respectively.2,5,6 To date, studies conducted among Cambodian FESWs have not explored specific factors associated with LTFU in this population.

The Cambodia Integrated HIV and Drug Prevention Intervention (CIPI) trial was designed to assess the impact of a comprehensive package of interventions designed to prevent HIV by reducing sexual risk and ATS use among high-risk FESWs.13,14 Data collected as part of the trial present an opportunity to examine predictors of LTFU among Cambodian FESWs participating in longitudinal research.

Methods

CIPI enrolled and followed women between June 2013 and December 2016. Full descriptions of the protocol and intervention methods have been previously published but are described briefly below.13,14 This study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) (No. 12-08589) on 29 March 2012, the Cambodia’s National Ethics Committee for Human Research (No. 0038 NECHR) on 1 March 2013, and FHI360’s Protection Human Subject Committee (No. 404710) on date 11 March 2013. The University of New Mexico and the University of New South Wales had reliance agreements recognizing the UCSF IRB determination. All women provided oral informed consent (signed consent was waived) prior to participation.

Study setting and intervention

The CIPI study was implemented in ten provinces, which were randomized to receive the study intervention sequentially in a step wedge randomized cluster study design. This study design is often used in implementation science research to study treatments that can be delivered only in a group setting (e.g. education), or to avoid contamination in the delivery of each regimen (e.g. a behavioural intervention that could be delivered individually, but where randomization may not impede close contact between study subjects). Clusters, in this case, provinces are identified and randomized prospectively to receive the experimental condition in a step-wise fashion.15 The CIPI programme had four components: (1) Expanded outreach to engage high-risk FESWs in existing HIV prevention services, the number of outreach workers and activities, including hours and recruitment locations, was expanded; (2) ATSs and alcohol screening using the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST)16,17 as well as urine toxicology screening for recent ATS use, with brief counselling for those who screened positive for problematic ATS and/or alcohol use; (3) FESWs with problematic ATS use at baseline (based on ASSIST results and urine toxicology screening) were offered a 12-week conditional cash transfer (CCT) intervention targeting ATS use followed by four-week, cognitive- behavioural aftercare (AC) group; (4) a microenterprise (ME) opportunity for women who tested ATS toxicology negative at six months or who had completed the CCT and AC groups, and which included a three-day financial literacy training with the option to apply for a microloan. CIPI leveraged SMARTgirl, an established and widely disseminated HIV prevention platform targeting FESWs in Cambodia initiated in 2008.18,19 SMARTgirl provides peer education; social support; and referrals to HIV, STIs, and reproductive health services.18,19 Participants were aged 18 years or older, who understood spoken Khmer, were biologically female, reported two or more transactional sexual partners in the past month, and could provide voluntary informed consent. In each province, targeted participant recruitment and follow-up outreach for CIPI study participants was conducted by trained outreach workers who were part of ongoing community programmes locally. All women who were not already members were invited to join the SMARTgirl programme.18,19

At enrolment (baseline) women were surveyed regarding socio-demographic factors (e.g. age, marital status, number of children, and time living in the specific province). That visit and all subsequent study visits included further assessments for occupational factors (e.g. the type of venue they worked at, whether they had a boss or manager), assessments for ATSs and alcohol disorder using the ASSIST20; urine toxicology testing for recent ATS use; assessment of sexual risk by self-report and prostate-specific antigen testing (a biomarker of unprotected sex).21 Measures of wellbeing included income, food insecurity, and housing instability. Food insecurity was defined as reporting ‘sometimes’, ‘always’, or ‘usually’ ‘having no food to eat of any kind in the household because of lack of money or resources to get food in the last three months’.22 Housing instability was measured by asking ‘In the past three months, how often did you worry about having a place to stay for you or your family because of lack of resources or money for housing?’.23

Follow-up procedures

The CIPI study design included a target of enrolling and assessing 1200 women for an initial visit. Three subsequent six-month follow-up visits then followed. A total of 600 enrolled FESWs were purposively targeted for follow-up assessments at each of the three six-monthly follow-up assessments to measure the effectiveness of the CIPI multi-level intervention. For the 12-month follow-up, we primarily targeted women who participated in the six-month visit for follow-up and similarly, women in the 18-month follow-visits were, to the extent possible, targeted from those who participated in the 12-month visit. To assess LTFU in this study, we anchored data at the six-month outcome evaluation visit and assessed losses at the subsequent 12- and 18-month outcome evaluation visits relative to the six-month visit. The baseline preintervention sample of women (N = 1198) could not be used to evaluate LTFU since the design was purposefully targeting outcome evaluation follow-up visits to half the number of women (N = 600). Thus, losses between baseline and six-month were not ‘natural’ losses.

At each visit, participants were given appointment cards and asked to return to the CIPI study site for follow-up in six months. Contact information was elicited including a phone number, home address, and workplace address to facilitate follow-up reminders and tracking. Approximately two weeks prior to scheduled appointments, outreach workers attempted to locate participants to remind them about upcoming visits in person and, or by telephone if available. Women received a remuneration of US$4 for completing the six- and 12-month follow-up visits and US$8 for completing the 18-month visit. All participants were also offered US$2 for transportation or free transportation, as well as refreshments and condoms at all visits.

Analyses

The primary outcome of interest was the proportion of LTFU measured at the 12- and 18-month follow-up visits relative to the women who participated in the six-month visit. Participants were coded as LTFU if (1) they missed the 18-month visit, or (2) missed both 12- and 18-month visits. We assessed the association between LTFU and the following variables collected at baseline: socio-demographic characteristics; sexual and drug use exposures (by self-report and biomarker); measures of income, housing instability, and food insecurity; and participation in SMARTgirl. The proportion of LTFU was calculated by dividing total LTFU individuals by total participants enrolled at six-month follow-up visit. To identify factors associated with LTFU, we first conducted unadjusted logistic regression analysis. We included variables with p <0.25 in the multivariate regression model. In addition to p-values, variables perceived a priori (e.g. SMARTgirl membership) and known potential confounders (like age) were included. We then eliminated variables with the highest p-value from the model. To ensure we did not eliminate potential interacting variables, we tested for interaction prior to finalizing the model. We repeated this until we had all variables with p <0.05 in the final model. Analyses were conducted using STATA (Version 14.1 for Windows, Stata Corp, TX, US).

Results

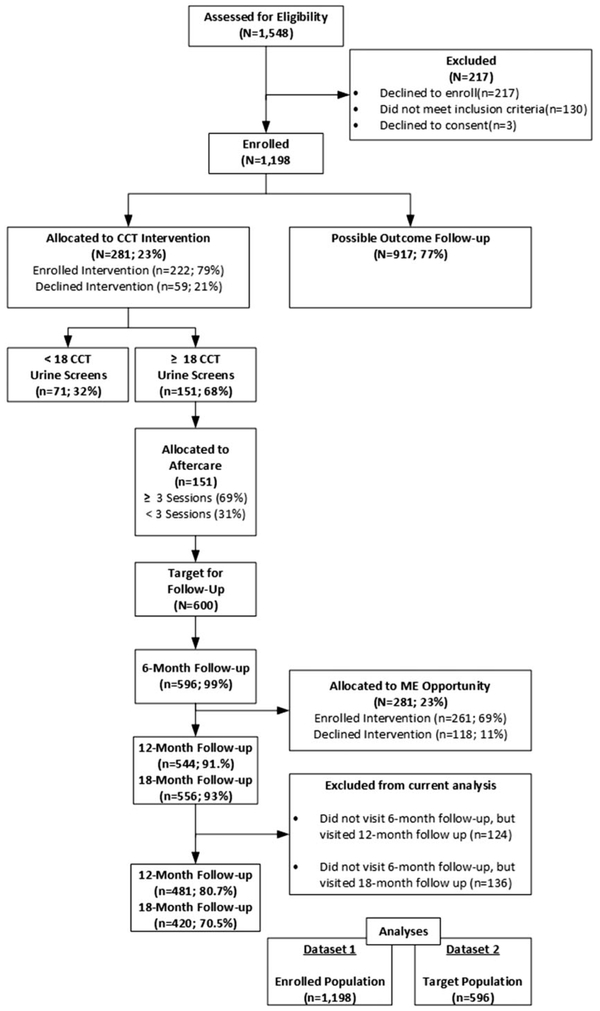

Of the 596 FESWs who were seen at the anchor outcome evaluation (at six-month) visit (t0), 80.7% (n = 481) returned six months later at the 12-month visit (t1) and 70.5% (n = 420) were seen at the 18-month follow-up visit (t2) in the present study (Figure 1). A total of 115 women (19.3%) missed between (t0) and t(1), and a total of 61 (12.6%) missed the t(1) and t(2). The cumulative proportion of women who lost to follow-up between the (t0) and (t2) was 29.5%.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. CCT: conditional cash transfer; ME: micro-enterprise.

Table 1 summarizes socio-demographic, behavioural, and other characteristics of participants, LTFU proportion, and factors associated with attrition in bivariate analyses. The median age of women was 27 years (interquartile range 23, 31), two-thirds (68.1%) had six or fewer years of education, over half the women (58.7%) had one or more living children, and 37.4% reported cohabiting with a partner(s). The majority (80.0%) of women worked in entertainment venues such as karaoke bars, massage parlours, beer gardens, or nightclubs. One-fifth of participants (20.6%) reported food insecurity and almost half (44.4%) reported housing instability in the previous three months. Most women (84.1%) had been registered with the SMARTgirl programme for more than six months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and unadjusted factors associated with loss to follow-up in bivariate logistic regression model (N = 596).

| Total (N=596) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at baseline | n (column %) |

LTFU proportion (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) |

p-value |

| Age (years, median [IQR]) | 27 (23–31) | |||

| 18–24 | 217 (36.4) | 30.4 (24.6, 36.9) | Ref. | 0.546 |

| 25–29 | 184 (30.9) | 31.5 (25.2, 38.6) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) | |

| ≥30 | 195 (32.7) | 26.7 (20.9, 33.3) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) | |

| Schooling (in years, median [IQR]) | 5 (2–7) | |||

| 0–6 years | 406 (68.1) | 30.9 (25.7, 37.1) | Ref. | 0.271 |

| 7–12 years | 190 (31.9) | 36.7 (28.6, 47.1) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| No cohabiting partner | 373 (62.6) | 26.8 (22.5, 31.6) | Ref. | 0.061 |

| Having cohabiting partner | 223 (37.4) | 34.1 (28.1, 40.6) | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0) | |

| Has living children | ||||

| Yes | 350 (58.7) | 26.6 (22.2, 31.5) | Ref. | 0.060 |

| No | 246 (41.3) | 33.7 (28.1, 39.9) | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0) | |

| Period of living in current city/province (in years, median [IQR]) | 7 (2–15) | |||

| <2 years | 170 (28.5) | 27.6 (21.4, 34.9) | Ref. | 0.523 |

| ≥2 years | 426 (71.5) | 30.3 (26.1, 34.8) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.7) | |

| Provided telephone number at baseline for follow-up contact | ||||

| No | 191 (32.1) | 30.9 (24.7, 37.8) | Ref. | 0.178 |

| Yes | 321 (53.9) | 26.8 (22.2, 31.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | |

| Missing | 84 (14.1) | 36.9 (27.2, 47.8) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.2) | |

| Current job | ||||

| Working in entertainment venues (i.e. karaoke, restaurant) | 477 (80.0) | 27.3 (23.4, 31.4) | Ref. | 0.017 |

| Working in sex work venues | 119 (20.0) | 38.7 (30.3, 47.7) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | |

| Income (USD$, median [IQR]) | 225 (l25–375) | |||

| <100 | 67 (11.2) | 31.3 (21.3, 43.5) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8) | 0.507 |

| 100–200 | 214 (35.9) | 26.6 (21.1, 33.0) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | |

| >200 | 315 (52.9) | 31.1 (26.2, 36.5) | Ref. | |

| Type of household | ||||

| Own house | 54 (9.1) | 33.3 (22.0, 47.0) | Ref. | 0.618 |

| Rental house/room | 362 (60.7) | 29.6 (25.1, 34.5) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.5) | |

| Living at workplace | 174 (29.2) | 27.6 (21.4, 34.7) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | |

| Homeless | 6 (1.0) | 50.0 (14.7, 85.3) | 2.0 (0.4, 10.9) | |

| Food insecurity in the past three months | ||||

| No | 471 (79.4) | 26.1 (22.3, 30.3) | Ref. | <0.001 |

| Yes | 122 (20.6) | 41.8 (33.3, 50.8) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.1) | |

| Housing instability in the past three months | ||||

| No | 330 (55.7) | 27.6 (23.0, 32.7) | Ref. | 0.291 |

| Yes | 263 (44.4) | 31.6 (26.2, 37.4) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | |

| Alcohol disorder (ASSIST score) | ||||

| Minimal risk | 221 (37.1) | 29.0 (23.3, 35.3) | Ref. | 0.466 |

| Medium risk | 265 (44.5) | 31.7 (26.4, 37.6) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.7) | |

| High risk | 110 (18.5) | 25.5 (18.1, 34.5) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.4) | |

| Binge drinking (more than five drinks on one day or night in the past three months) | ||||

| Never | 165 (27.7) | 32.7 (26.0, 40.3) | Ref. | 0.446 |

| Monthly or less | 76 (12.8) | 25.0 (16.5, 36.0) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.3) | |

| Weekly/daily | 355 (59.6) | 29.0 (24.5, 34.0) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.3) | |

| Positive ATS urine screen (indicating recent use, last 48 hours) | ||||

| Negative | 485 (81.4) | 29.7 (25.8, 33.9) | Ref. | 0.692 |

| Positive | 111 (18.6) | 28.8 (21.1, 38.0) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.5) | |

| ATS disorder (ASSIST score) | ||||

| Minimal risk | 423 (71.0) | 29.6 (25.4, 34.1) | Ref. | 0.804 |

| Medium risk | 138 (23.2) | 30.4 (23.3, 38.7) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.6) | |

| High risk | 35 (5.9) | 25.7 (13.8, 42.8) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | |

| SMARTgirl membership | ||||

| No, I am not a member | 59 (9.9) | 54.2 (41.4, 66.5) | Ref. | <0.001 |

| Yes, during past six months | 36 (6.0) | 47.2 (31.5, 63.5) | 0.8 (0.3, 1.7) | |

| Yes, more than six months | 501 (84.1) | 25.3 (21.7, 29.4) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.5) | |

| Sexual risk No. of sexual partners past three months | ||||

| 2–4 | 308 (51.9) | 26.6 (22.0, 31.9) | Ref. | 0.122 |

| ≥5 | 286 (48.2) | 32.4 (27.2, 38.1) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) | |

| Condomless sex in the past 72 hours (prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test) | ||||

| Positive | 153 (25.8) | 33.3 (26.3, 41.2) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) | 0.232 |

| Negative | 440 (74.2) | 28.2 (24.2, 32.6) | Ref. | |

| Self-reported condomless sex with any of last three partners in the past three months | ||||

| Always use | 328 (55.0) | 31.4 (26.6, 36.6) | Ref. | 0.699 |

| Not always | 268 (45.0) | 27.2 (22.2, 32.9) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | |

| Mental health (measuring by Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [K10]) | ||||

| Well | 430 (72.3) | 30.0 (25.8, 34.5) | Ref. | 0.567 |

| Mild mental disorder | 89 (15.0) | 23.6 (l5.9, 33.6) | 0.7 (0.4 1.2) | |

| Moderate mental disorder | 43 (7.2) | 32.6 (20.2, 48.0) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.2) | |

| Severe mental disorder | 33 (5.6) | 33.3 (19.3, 51.1) | 1.2 (0.5, 2.5) | |

ATS: amphetamine-type stimulant; CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range; LTFU: loss to follow-up; n: number of sub-total; N: number of the total; OR: odds ratio; ref: reference group; USD: US Dollars.

Based on unadjusted logistic regression analyses, the following variables were included in the multivariable model: marital status, parity, not providing a phone number, work venue, food insecurity, housing insecurity, SMARTgirl programme registration, having more than five sexual, and having a condomless sex (Table 1). Factors found to be independently associated with LTFU included parity, food insecurity, and SMARTgirl membership (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted factors associated with loss to follow-up in multivariate logistic regression model

| Characteristics at baseline | Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) |

95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Having living children | |||

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| No | 1.6 | 1.1, 2.3 | 0.020 |

| Food insecurity in the past three months | |||

| No | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 1.7 | 1.1, 2.7 | 0.013 |

| SMARTgirl membership | |||

| Never | Ref. | ||

| Six or less months | 0.8 | 0.4, 2.0 | 0.685 |

| More than six months | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.6 | <0.001 |

AOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; Ref: reference group.

Discussion

Our results provide important insights into the factors associated with LTFU among Cambodian FESWs participating in a longitudinal study. The proportion of women LTFU in this study, 29.5%, is comparable to that reported by other studies in similar populations which have reported 23–27% of women lost.2,5,6

However, it was substantially lower than the 51% found in cohort of FESWs in Phnom Penh that was initiated in the early 2000s but subsequently stopped as a result.12 Since our design had only two time points at which to assess follow-up over a 12-month period we were unable to calculate an estimated rate of LTFU per person-years of observation (PYO), limiting comparability to other studies which report rates in PYO. Nevertheless, the observed proportion of LTFU in our study was comparable to results of a study of female sex workers in Kenya ([23/100 PYO; 95%CI: 21.9, 24.9] and a study in China [29.7/100 PYO; 95% CI: 27.9, 31.6]).24,25

Variables independently associated with LTFU in this study provide important insights into factors impacting retention in this population. FESWs who reported food insecurity were more likely to be LTFU compared to those who did not. Food insecurity has also been found to be associated with poor adherence to HIV treatment in studies in sub-Saharan Africa,26–35 the US,36–39 Canada,40 and Honduras.41 FESWs who face food insecurity may have more instability in their daily lives and have significant competing priorities that impact participation in research. Our findings are in line with these studies and suggest that additional research is needed on how to minimize food insecurity to help overcome the destabilizing effects of this hardship on engagement and retention. A systematic review by Tirivayi and Groot42 suggested that providing food assistance could improve the adherence to HIV treatment. This kind of intervention in a research setting might only be a short-term approach, implemented in a small scale, given resource limitations. For a bigger scale or longer term structural solution, addressing food insecurity must involve all level policymakers to increase the job opportunities, decrease the food prices, increase farming, or promote small-scale enterprises, etc. going beyond what public health research can do.

Membership in the SMARTgirl programme emerged as significant and independent positive predictor of retention in our study. This finding is important because SMARTgirl has high programme coverage and high ‘brand-name’ recognition among FESWs in Cambodia. We are unable to measure how and by what mechanism SMARTgirl optimized retention. However, we hypothesize that group engagement, and factors like the safe space that SMARTgirl offers may contribute positively to retention and reduce the desire or need to relocate. Women may have also developed relationships with SMARTgirl programme’s outreach workers or staff that support positive engagement and retention. We have previously shown that SMARTgirl membership was a significant predictor of retention in HIV treatment among HIV-positive FESWs.43

Women without living children compared to those with living children were also more likely to be LTFU in this study. Additional sub-analysis (data not shown) revealed that these women were significantly younger than those with children, less likely to cohabit with a partner, and had a shorter period of residence in the city in which they were enrolled, suggesting that they were more mobile. A similar finding was found in a study of LTFU among female sex workers in China.25 There is a need for studies of the natural history of sex work in different settings which explore the relationships between age, childlessness, and mobility in this population. For women who are young and more mobile, informing women in advance that they can ‘transfer’ their programme membership to other locations could help to minimize attrition.

We noted that LTFU was not different between those who provided the research team with a contact phone number at baseline and those who did not. It is common for FESWs in Cambodia to change their phone numbers, especially when they relocate, and outreach workers used various methods to locate women including by direct contact at their living place or workplace. No associations were found between LTFU and risk behaviours, including between ATS use and sexual risk behaviour, the principal exposures, and outcomes in the CIPI trial.

Our study has several limitations. First, we only calculated the proportion of LTFU among women already enrolled in the study – using the six-month visit as the anchor point. These women may have been relatively stable compared to baseline, and it is possible that women who were more likely to be LTFU may have already lost prior to our six-month entry point, underestimating the proportion of LTFU rate in our study. In addition, women who did not complete the six-month visit could participate in the 12- and 18-month visits. If outreach workers met the target number, they might not have been diligent in trying to get the same women back, which would have the effect of inflating our estimate of LFTU. The CIPI study targeted high-risk FESWs, and as such, our sample may not represent the population of FESWs in Cambodia who are a highly heterogeneous group. For example, this study focused on women who were venue based (both entertainment and freelance), and it is unknown if women recruit male partners from the internet or other sources. Nevertheless, the large sample size and the wide geographic area from where participants were recruited means that our findings are highly relevant to FESWs at risk of HIV.

Conclusion

LTFU among FESWs in this study was moderately high but similar to that observed in other studies of female sex workers. There is a need for strategies designed to increase engagement in order to retain this population in HIV prevention programmes and related research. Results suggest that interventions aimed at stabilizing women’s lives, including reducing food insecurity and creating communities of engagement for FESWs as using technologies, such as mobile phone apps that might increase geographic access for mobile FESWs should be considered.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the women who participated in the study. We also wish to acknowledge the important role the FHI360 field team had in data collection, including: Len Aynar for later stage oversight of data collection and management; Ean Nil for working closely with our team to develop and implement the CCT + AC intervention; Hong Naysim for her invaluable work in the field as a supervisor and facilitator for the AC groups; Nith Sopha and Mech Sotheary for their efforts in development of the ME financial literacy training curriculum; and Amy Weissman for supporting the implementation of this project in its early phases. We acknowledge the substantive contributions by Dr Marie-Claude Couture to development of various study instruments and materials in the study planning phase. The authors would like to acknowledge the gracious and considerate involvement of the following organizations which supported the study and the participants: Provincial Health Departments (PHD), Provincial AIDS and STI program (PASP), Chouk Sar Association and AID Health Foundation (AHF). The authors are indebted and grateful for the ongoing support of numerous non-governmental organizations which made the implementation of this project possible: Cambodian Women for Peace and Development (CWPD), Poor Family Development (PFD), KHEMERA, Phnom Srey Organization for Development (PSOD), Chamroen Microfinance Limited, and Vision Fund Cambodia. Finally, this research would not be possible without the support from the Cambodia National Ministry of Health Department Mental Health and Substance Abuse, the National Authority for Combating Drugs, and the National Center for HIV, AIDS, Dermatology and STDs.

We also thank Field Research Training Program team, especially Liza Doyle, Cui Haixia, and Kathy Petoumenos who coordinated and provided us scientific writing training.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA033672). Lisa Maher is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

Data used for analysis cannot be made available in the manuscript, the supplemental files, or a public repository. However, data can be accessed upon request from the Principal Investigator Kimberly Page at pagek@salud.unm.edu.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12: 538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page K, Stein E, Sansothy N, et al. Sex work and HIV in Cambodia: trajectories of risk and disease in two cohorts of high-risk young women in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e003095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phalkun M Integrated HIV Bio-Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS 2016) among female entertainment workers. Phnom Penh: National Center for HIV/AIDS Dermatology and STD (NCHADS), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chhorvann C and Vonthanak S. Estimations and projections of HIV/AIDS in Cambodia 2010–2015. Phnom Penh: National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology and STDs (NCHADS), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couture MC, Sansothy N, Sapphon V, et al. Young women engaged in sex work in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, have high incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections, and amphetamine-type stimulant use: new challenges to HIV prevention and risk. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38: 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couture MC, Evans JL, Sothy NS, et al. Correlates of amphetamine-type stimulant use and associations with HIV-related risks among young women engaged in sex work in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012; 120: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadhera P, Evans JL, Stein E, et al. HPV knowledge, vaccine acceptance, and vaccine series completion among female entertainment and sex workers in Phnom Penh, Cambodia: the Young Women’s Health Study. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26: 893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristman V, Manno M and Cote P. Loss to follow-up in cohort studies: how much is too much? Eur J Epidemiol 2004; 19: 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dettori JR. Loss to follow-up Evid Based Spine Care J 2011; 2: 7–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maher L, Page K, Commentary On S, et al. Reducing bias in prospective observational studies of drug users: the need for upstream and downstream approaches. Addiction 2015; 110: 1259–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sopheab H, Gorbach P, Detels R, et al. The Cambodian young women’s cohort Phnom Penh National Center of HIV/AIDS Dermatology and STDs. Los Angeles: University of California, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrico AW, Nil E, Sophal C, et al. Behavioral interventions for Cambodian female entertainment and sex workers who use amphetamine-type stimulants. J Behav Med 2016; 39: 502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page K, Stein ES, Carrico AW, et al. Protocol of a cluster randomised stepped-wedge trial of behavioural interventions targeting amphetamine-type stimulant use and sexual risk among female entertainment and sex workers in Cambodia. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e010854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellenberg SS. The stepped-wedge clinical trial: evaluation by rolling deployment. JAMA 2018; 319: 607–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO. Management of substance abuse: The ASSIST project – alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Group WHOAW. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction 2002; 97: 1183–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FHI360. SMARTgirl: Empowering women in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: FHI360, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.FHI360. Mid-term review for SMARTgirl Program: Providing HIV/AIDS prevention care and support to men who having sex with men (MSM). Phnom Penh; FHI 360, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction 2012; 107: 957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans JL, Couture M-C, Stein ES, et al. Biomarker validation of recent unprotected sexual intercourse in a prospective study of young women engaged in sex work in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40: 462–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennifer C, Anne S and Paula B. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access. Washington, D.C: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prevention; CfDCa. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham SM, Raboud J, McClelland RS, et al. Loss to follow-up as a competing risk in an observational study of HIV-1 incidence. PLoS One 2013; 8: e59480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su Y, Ding G, Reilly KH, et al. Loss to follow-up and HIV incidence in female sex workers in Kaiyuan, Yunnan province China: a nine year longitudinal study. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagata JM, Magerenge RO, Young SL, et al. Social determinants, lived experiences, and consequences of household food insecurity among persons living with HIV/AIDS on the shore of Lake Victoria, Kenya. AIDS Care 2012; 24: 728–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iroezi ND, Mindry D, Kawale P, et al. A qualitative analysis of the barriers and facilitators to receiving care in a prevention of mother-to-child program in Nkhoma, Malawi. Afr J Reprod Health 2013; 17: 118–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musumari PM, Feldman MD, Techasrivichien T, et al. “If I have nothing to eat, I get angry and push the pills bottle away from me”: a qualitative study of patient determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Care 2013; 25: 1271–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fielding-Miller R, Mnisi Z, Adams D, et al. “There is hunger in my community”: a qualitative study of food security as a cyclical force in sex work in Swaziland. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musumari PM, Wouters E, Kayembe PK, et al. Food insecurity is associated with increased risk of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a crosssectional study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e85327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiser SD, Palar K, Frongillo EA, et al. Longitudinal assessment of associations between food insecurity, antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes in rural Uganda. AIDS 2014; 28: 115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coetzee B, Kagee A and Bland R. Barriers and facilitators to paediatric adherence to antiretroviral therapy in rural South Africa: a multi-stakeholder perspective. AIDS Care 2015; 27: 315–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sellers CJ, Lee H, Chasela C, et al. Reducing lost to follow-up in a large clinical trial of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: the Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals and Nutrition study experience. Clin Trials 2015; 12: 156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koole O, Denison JA, Menten J, et al. Reasons for missing antiretroviral therapy: results from a multi-country study in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0147309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS, et al. Food insufficiency, depression, and the modifying role of social support: evidence from a population-based, prospective cohort of pregnant women in peri-urban South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2016; 151: 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiser SD, Yuan C, Guzman D, et al. Food insecurity and HIV clinical outcomes in a longitudinal study of urban homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 2013; 27: 2953–2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalichman SC, Hernandez D, Cherry C, et al. Food insecurity and other poverty indicators among people living with HIV/AIDS: effects on treatment and health outcomes. J Community Health 2014; 39: 1133–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y and Kalichman SC. Synergistic effects of food insecurity and drug use on medication adherence among people living with HIV infection. J Behav Med 2015; 38: 397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colasanti J, Stahl N, Farber EW, et al. An exploratory study to assess individual and structural level barriers associated with poor retention and re-engagement in care among persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74: S113–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anema A, Kerr T, Milloy MJ, et al. Relationship between hunger, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and plasma HIV RNA suppression among HIV-positive illicit drug users in a Canadian setting. AIDS Care 2014; 26: 459–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez H, Palar K, Linnemayr S, et al. Tailored nutrition education and food assistance improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: evidence from Honduras. AIDS Behav 2014; 18: S566–S577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tirivayi N and Groot W. Health and welfare effects of integrating AIDS treatment with food assistance in resource constrained settings: a systematic review of theory and evidence. Soc Sci Med 2011; 73: 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muth S, Len A, Evans JL, et al. HIV treatment cascade among female entertainment and sex workers in Cambodia: impact of amphetamine use and an HIV prevention program. Addiction science & clinical practice 2017; 12: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]