Key Points

Question

What is the effect of a culturally tailored patient navigator intervention on advance care planning, pain management, and hospice use?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 223 Latino adults with advanced cancer, the advance directive documentation rate was 73 of 112 with navigator visits and 40 of 111 without navigator visits, a significant difference. There were no differences in pain management and hospice use between groups, with a mean pain rating of 3 of 10 (mild pain) and with hospice use in 98 of 120.

Meaning

Bicultural patient navigators may help Latino patients with cancer complete advance care planning; there was no benefit for pain management or hospice use.

This randomized clinical trial investigates if a culturally tailored patient navigator intervention can improve palliative care outcomes for Latino patients with advanced cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Strategies to increase access to palliative care, particularly for racial/ethnic minorities, must maximize primary palliative care and community-based models to meet the ever-growing need in a culturally sensitive and congruent manner.

Objective

To investigate if a culturally tailored patient navigator intervention can improve palliative care outcomes for Latino adults with advanced cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) randomized clinical trial was conducted from July 2012 to March 2016. The setting was clinics across the state of Colorado, including an academic National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center, community cancer clinics (urban and rural), and a safety-net cancer center. Participants were adults who self-identified as Latino and were being treated for advanced cancer.

Intervention

Culturally tailored patient navigator intervention.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome measures were advance care planning in the medical record, the Brief Pain Inventory, and hospice use. Secondary outcome measures included the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL), hospice length of stay, and aggressiveness of care at the end of life. This study used an intent-to-treat design.

Results

In total, 223 Latino adults enrolled (mean [SD] age, 58.1 [13.6] years; 55.6% female) and were randomized to control (n = 111) or intervention (n = 112) groups. Intervention group patients were more likely to have a documented advance directive compared with control group patients (73 of 112 [65.2%] vs 40 of 111 [36.0%], P < .001). Both groups reported mild pain intensity (mean pain rating of 3 on a scale of 0-10). Intervention group patients had a mean (SD) reported change from baseline in the Brief Pain Inventory pain severity subscale score (range, 0-10) of 0.1 (2.6) vs 0.2 (2.7) in control group patients (P = .88) and a mean (SD) reported change from baseline in the Brief Pain Inventory pain interference subscale score of 0.1 (3.2) vs −0.2 (3.0) in control group patients (P = .66). Hospice use was similar in both groups. Secondary outcomes of overall MQOL score and aggressiveness of care at the end of life showed no significant differences between groups. The MQOL physical subscale showed a mean (SD) significant change from baseline of 1.4 (3.1) in the intervention group vs 0.1 (3.0) in the control group (P = .004).

Conclusions and Relevance

The intervention had mixed results. The intervention increased advance care planning and improved physical symptoms; however, it had no effect on pain management and hospice use or overall quality of life. Further research is needed to determine the role and scope of lay navigators in palliative care.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01695382

Introduction

Latinos are more likely to die in an institution,1 are less likely to receive adequate pain control,2 and less often receive hospice services than nonminorities.3 Early patient-centered, specialty palliative care (PC) improves quality of life (QOL), symptom burden, and advance care planning (ACP) for patients with cancer, ensuring that care is congruent with patient goals, values, and preferences.4,5 Specialty-level PC (tertiary palliative care) cannot grow fast enough to meet demand6; therefore, primary PC models are required, especially in poor urban and rural settings.7 Minority patients are consistently underrepresented in PC trials, increasing the gap in quality PC outcomes.8 Cultural and linguistic barriers also increase PC disparities.

Patient navigators (PNs) have reduced health disparities in underserved, vulnerable populations by improving cancer screening, follow-up on abnormal test results, and treatment adherence.9 Research examining PN interventions to improve PC for patients with advanced cancer is limited.10

The objective of this study was to investigate if a culturally tailored PN intervention can improve PC outcomes (increased ACP, improved pain management, and greater hospice use) for Latino adults with advanced cancer. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01695382), and the trial protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Methods

Sample

The Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) randomized clinical trial was conducted from July 2012 to March 2016. The setting was clinics across the state of Colorado, including an academic National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center, community cancer clinics (urban and rural), and a safety-net cancer center. Patients were recruited from 3 Colorado urban (academic comprehensive cancer center at University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center, Aurora; community cancer center at Cancer Center of Colorado, St Joseph Hospital, Denver; and safety-net cancer center at Denver Health Medical Center, Denver) and 7 Colorado rural (Alamosa, Aspen, Edwards, Glenwood Springs, Grand Junction, Pueblo, and Rifle) community cancer clinics and screened for eligibility (age ≥18 years, self-identified as Latino, spoke either English or Spanish as the primary language at home, and diagnosed as having stage III/IV cancer) by oncology staff (S.O.-S. and other nonauthors). Exclusion criteria included lack of decisional capacity, referred or enrolled in hospice, incarceration, and pregnancy. Recruitment processes have been previously reported.11 The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Group Randomization

Patients were randomized using a 1:1 assignment (control vs intervention) after consent and baseline data collection. Randomization was stratified by site with computer-generated blocks (randomly varying 2-6 per block). Patient navigators were unmasked at group assignment; other team members (S.M.F., D.M.K., S.-J. M., and R.M.F.) remained masked.

All participants (control and intervention) received a culturally tailored packet of written information about ACP, pain management, hospice use, and a study-specific advance directive (AD).12 Materials were at a fifth-grade reading level and available in English and Spanish, per patient preference. An interdisciplinary, bicultural community advisory panel helped select materials.10,13

Intervention

Intervention patients received at least 5 home visits from a PN and the educational packet. Patient navigator training and intervention content details are available in the eAppendix and eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Patient navigators completed detailed field notes, including tracking the number of contacts and visit length and content. The research team reviewed field notes to ensure intervention fidelity.

Primary Outcome Measures

Several primary outcomes were addressed. These included ACP (electronic health record [EHR] documentation of Medical Durable Power of Attorney, study-specific AD, or other type of comprehensive AD), pain management (Brief Pain Inventory [BPI]), and hospice use (measured in all patients who died during the study).

Secondary Outcome Measures

Patients completed a sociodemographic survey, the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL), and the Patient Navigation Process and Outcomes Measure (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Hospice length of stay and a measure of aggressiveness of care at the end of life (chemotherapy within 14 days of death, no hospice use, or ≤3 days of hospice use before death) were also assessed.

Data Collection

Patient navigators collected baseline measures via in-person survey immediately after consent and before randomization. Masked study personnel (D.M.K.) surveyed patients by telephone interview 3 months after enrollment to complete patient-centered measures. On completion of follow-up surveys, patients were asked if they had PN visits; if so, additional questions about satisfaction were completed. At month 46, EHRs were reviewed for ACP documentation, hospice use, and aggressiveness of care at the end of life for patients who died during the course of the study. Study processes and satisfaction with the intervention were measured using the Patient Navigator Process and Outcome Measures Survey. This study used an intent-to-treat design.

Statistical Analysis

To assess randomization effectiveness, both groups were compared on participant-level variables, including age, sex, degree of acculturation (primary language at home), socioeconomic status, and diagnoses. To test the effect of the intervention on process and outcome measures and for baseline comparisons, t tests (or Wilcoxon rank sum tests if the distribution was not normal) were used for continuous measures (age, BPI [pain severity subscale and pain interference subscale], MQOL, hospice use in days for decedents, etc). χ2 Tests (or Fisher exact tests if the cell size was <5) were used for dichotomous outcome measures (sex, AD documented in the EHR, hospice use, aggressiveness of care at the end of life, Patient Navigation Process and Outcomes Measure, etc). Satisfaction with the intervention was described using frequencies and proportions. Power calculations, based on a sample size of 186 patients after death and dropout, provided more than 90% power to detect a medium effect size of 0.25 for a 2-sided test comparing 2 means at a type I error rate of .05.

Results

Baseline Participant Characteristics

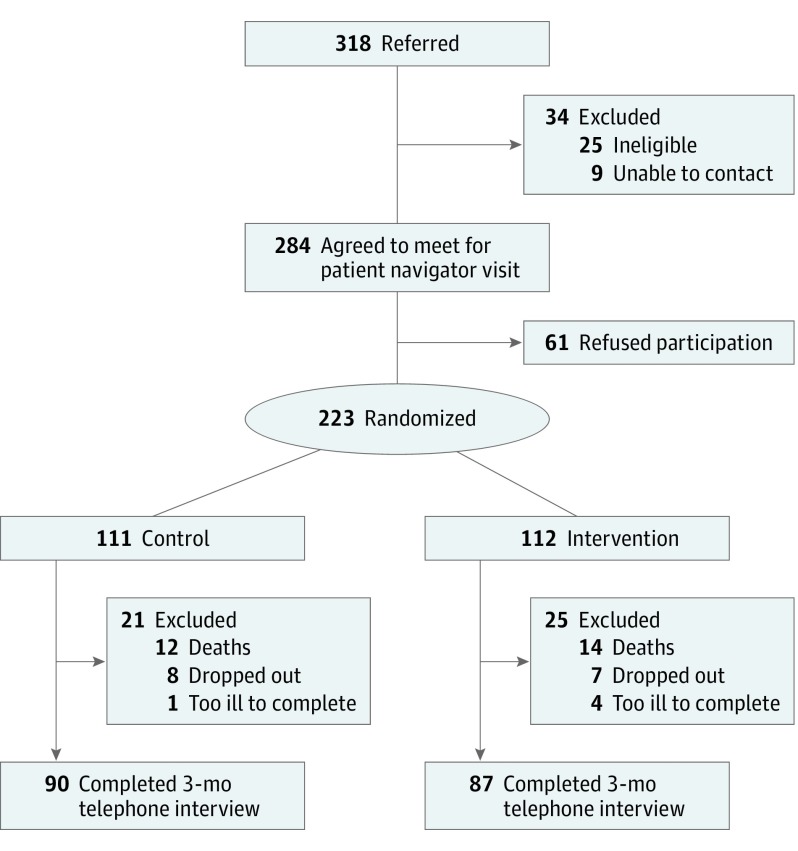

Overall, 318 patients were referred; 25 were ineligible. Patient navigators obtained consent from 223 Latino adults, resulting in a 78.5% (223 of 284) enrollment rate (Figure). Reasons for refusal to participate included not needing additional help, perceived study burden, and aversion to PC. There were no significant differences between groups (Table 1), with no adjustments of baseline covariates. The average patient had a mean (SD) age of 58.1 (13.6) years, was female, had less than a high school education, reported a low socioeconomic status (with an annual income less than $15 000), and had stage IV cancer. Close to 50% (106 of 223) primarily spoke Spanish. Missing data were negligible for primary outcome variables.

Figure. CONSORT Diagram of Patient Accrual for the Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) Trial.

CONSORT indicates Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Table 1. Patient Characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 223) | Control (n = 111) | Intervention (n = 112) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58.1 (13.6) | 58.6 (13.8) | 57.5 (13.3) |

| Female, No. (%) | 124 (55.6) | 65 (58.6) | 59 (52.7) |

| Married or domestic partner, No. (%) | 129 (57.8) | 63 (56.8) | 66 (58.9) |

| Spanish primary language spoken at home, No. (%) | 106 (47.5) | 52 (46.8) | 54 (48.2) |

| Less than high school education, No. (%) | 112 (50.2) | 56 (50.5) | 56 (50.0) |

| Less than $15 000 annual income, No./total No. (%) | 118/220 (53.6) | 54/110 (49.1) | 64/110 (58.2) |

| Not currently working, No./total No. (%) | 195/221 (88.2) | 99/111 (89.2) | 96/110 (87.3) |

| Payment, No./total No. (%) | |||

| Medicaid | 84/221 (38.0) | 36/110 (32.7) | 48/111 (43.2) |

| Medicare (Part A ± Part B) | 56/221 (25.3) | 32/110 (29.1) | 24/111 (21.6) |

| Other | 81/221 (36.7) | 42/110 (38.2) | 39/111 (35.1) |

| Recruitment area, No. (%) | |||

| Large metropolitan city, population >50 000 | 102 (45.7) | 51 (45.9) | 51 (45.5) |

| Smaller metropolitan area, population ≤50 000 | 40 (17.9) | 20 (18.0) | 20 (17.9) |

| Rural/mountain area, population <2500 | 81 (36.3) | 40 (36.0) | 41 (36.6) |

| Stage IV cancer, No./total No. (%) | 150/220 (68.2) | 71/109 (65.1) | 79/111 (71.2) |

| Cancer type, No. (%) | |||

| Breast | 43 (19.3) | 24 (21.6) | 19 (17.0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 75 (33.6) | 37 (33.3) | 38 (33.9) |

| Genitourinary | 26 (11.7) | 13 (11.7) | 13 (11.6) |

| Gynecologic | 23 (10.3) | 12 (10.8) | 11 (9.8) |

| Hematologic | 17 (7.6) | 8 (7.2) | 9 (8.0) |

| Lung | 20 (9.0) | 11 (9.9) | 9 (8.0) |

| Other | 19 (8.5) | 6 (5.4) | 13 (11.6) |

| Brief Pain Inventory (range, 0-10), mean (SD) score | |||

| Pain severity subscale | 3.1 (2.8) | 3.2 (2.9) | 2.9 (2.7) |

| Pain interference subscale | 3.7 (3.5) | 3.8 (3.5) | 3.5 (3.4) |

| McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (range, 1-10), mean (SD) score | |||

| Overall | 7.2 (2.0) | 7.1 (2.0) | 7.2 (2.1) |

| Physical subscale | 5.5 (2.7) | 5.5 (2.9) | 5.6 (2.6) |

| Emotional subscale | 6.6 (3.2) | 6.5 (3.2) | 6.7 (3.1) |

| Existential subscale | 8.0 (2.2) | 8.0 (2.0) | 7.9 (2.4) |

| Support subscale | 8.7 (2.0) | 8.6 (2.0) | 8.8 (2.0) |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. There were less than 3% missing data. Control and intervention groups were compared using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Intervention Delivery

All intervention patients completed at least 1 home visit with the PN; 81.3% (91 of 112) completed all 5 home visits. Intervention patients received a mean (SD) of 5.3 (1.9) home visits, lasting a mean (SD) of 105 (25) minutes per visit; 37 patients requested additional PN visits. Intervention group patients reported high satisfaction with PNs (eFigure in Supplement 2).

Advance Care Planning

Intervention patients were more likely to have any AD type documented in the EHR (73 of 112 [65.2%] vs 40 of 111 [36.0%], P < .001) compared with control patients (Table 2). Only intervention patients had a completed study-specific AD documented in the EHR (51 of 112 [45.5%] vs 0), and they were more likely to report that they had discussed future health care preferences with family members (83.5% [71 of 85] vs 55.2% [48 of 87], P < .001) and health care providers (60.0% [51 of 85] vs 35.2% [31 of 88], P = .001).

Table 2. Outcomes of the Patient Navigator Interventiona.

| Variable | Control (n = 111) | Intervention (n = 112) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advance Care Planning, No. (%) | |||

| Any form of AD documented in the EHR | 40 (36.0) | 73 (65.2) | <.001 |

| Living will documented in the EHR | 14 (12.6) | 44 (39.3) | <.001 |

| MDPOA documented in the EHR | 28 (25.2) | 69 (61.6) | <.001 |

| Study-specific AD documented in the EHR | 0 | 51 (45.5) | NA |

| Pain and Symptom Management | |||

| Brief Pain Inventory (range, 0-10), mean (SD) score | |||

| Pain severity subscale | 3.5 (2.9) | 2.9 (2.5) | .12 |

| Change from baseline | 0.2 (2.7) | 0.1 (2.6) | .88 |

| Pain interference subscale | 3.8 (3.6) | 3.4 (3.3) | .37 |

| Change from baseline | −0.2 (3.0) | 0.1 (3.2) | .66 |

| Need stronger pain medicine, No./total No. (%) | 16/63 (25.4) | 14/55 (25.5) | .99 |

| Need more pain medication than prescribed, No./total No. (%) | 15/64 (23.4) | 6/54 (11.1) | .08 |

| Concerned about using too much pain medication, No./total No. (%) | 20/64 (31.3) | 12/55 (21.8) | .25 |

| Having problems with adverse effects of medications, No./total No. (%) | 17/63 (27.0) | 15/55 (27.3) | .97 |

| McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (range, 1-10), mean (SD) score | |||

| Overall | 7.2 (2.1) | 7.7 (1.9) | .14 |

| Change from baseline | 0.04 (1.7) | 0.5 (2.0) | .08 |

| Physical subscale | 5.8 (2.9) | 6.8 (2.5) | .009 |

| Change from baseline | 0.1 (3.0) | 1.4 (3.1) | .004 |

| Emotional subscale | 6.8 (3.4) | 7.2 (3.0) | .41 |

| Change from baseline | 0.3 (3.2) | 0.5 (3.0) | .55 |

| Existential subscale | 7.9 (2.3) | 8.1 (2.1) | .45 |

| Change from baseline | −0.1 (2.0) | 0.2 (2.4) | .29 |

| Support subscale | 8.6 (2.1) | 8.8 (1.9) | .52 |

| Change from baseline | 0.1 (2.1) | −0.04 (2.1) | .72 |

| Hospice Use | |||

| Received hospice care, No./total No. (%) | 51/61 (83.6) | 47/59 (79.7) | .58 |

| Hospice length of stay, mean (SD), d | 58.5 (78.8)b | 54.7 (103.4)c | .63d |

Abbreviations: AD, advance directive; EHR, electronic health record; MDPOA, Medical Durable Power of Attorney; NA, not applicable.

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. There were 0% missing data for advance care planning, less than 3% missing data for pain and symptom management, and less than 1% missing data for hospice use. Unless otherwise indicated, control and intervention groups were compared using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Among 50 patients.

Among 45 patients.

Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Pain Management and QOL

Both groups reported mild pain intensity (mean pain rating of 3 on a scale of 0-10). Intervention group patients had a mean (SD) reported change from baseline in the BPI pain severity subscale score (range, 0-10) of 0.1 (2.6) vs 0.2 (2.7) in control group patients (P = .88) (Table 2). Scores on the BPI pain interference subscale were also mild (<4 of 10); changes were not significantly different between groups. The secondary outcome of MQOL score was high, and the mean change from baseline did not differ significantly between groups. However, intervention patients had a larger mean (SD) change from baseline on the MQOL physical subscale compared with control patients (1.4 [3.1] vs 0.1 [3.0], P = .004).

Hospice and Health Care Use

Over the study period, 121 patients died. Of these, hospice use was high in both groups: 79.7% (47 of 59) of decedents in the intervention group vs 83.6% (51 of 61) of decedents in the control group enrolled in hospice (P = .58) (Table 2). There were no significant differences between groups in the secondary outcomes of hospice length of stay or aggressiveness of care at the end of life.

Discussion

To our knowledge, Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) is the first randomized clinical trial of a culturally tailored PN intervention addressing PC disparities for Latinos with advanced cancer. This study demonstrated a high enrollment rate using scientifically rigorous methods. While the intervention had a significant effect on increasing ACP documentation, there was no effect on pain management and hospice use. Secondary outcomes demonstrated an improvement in the MQOL physical subscale score but no effect on overall QOL or aggressiveness of care at the end of life.

What distinguishes this culturally tailored PN intervention from other PC interventions is that the PNs are not directly providing care. Instead, they are trained laypersons empowering and activating patients to seek improved primary PC from their oncologists. We designed the Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) intervention to use lay navigators to allow for possible future scalability and to foster trust within an underserved population consistent with the original PN model by Freeman et al.9 This study helps to inform the role of the lay PN in the care of underserved cancer populations and determine which aspects of care may require higher-intensity interventions delivered by nurses or specialty PC providers.

We found low rates of pain in both groups. With mean pain scores in the mild category, it is arguably difficult to further improve mild pain. However, some patients reported more moderate pain levels. The lack of effect of the intervention on pain may be related to the PN skill set; it is possible that an oncology nurse may have substantially influenced pain outcomes. However, a nurse-led intervention with underserved rural patients with cancer did not improve symptom intensity in another study.14 Also, if baseline pain levels had been higher, the intervention may have had a greater effect on clinical improvement in pain scores.15

In our overall sample, 81.7% (98 of 120) of the patients enrolled in hospice, well above previously reported national averages of a 40% Hispanic enrollment.16,17 The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization reports that, over the past decade, 6% to 8% of hospice patients have been Hispanic.3 However, the US Hispanic population is young, and, accounting for crude death rates among Hispanics, the hospice enrollment rate for Hispanic deaths is 38%.3,18 Similar rates of Hispanic hospice enrollment have been found in cancer-specific populations.16 Our study rates of hospice use did not significantly vary across Colorado’s urban and rural sites, suggesting that this high rate of hospice use is a statewide phenomenon. It is unclear how the culturally tailored PN intervention may have affected these rates. One possibility is that we may have had contamination from the intervention because many of the sites had only 1 practicing oncologist.

Intervention group patients had higher ACP rates, both in process measures and in EHR documentation. A recent Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services demonstration project confirmed that community-based layperson PNs can be effective in helping patients complete ADs.19 Furthermore, community grassroots efforts have shown that widespread adoption of ACP is possible and effective.20 Unlike pain management and hospice use, the ACP aspect of this intervention did not require a motivated patient to work with his or her health care provider. The PN directly facilitated a conversation about goals and values and helped the patient complete an AD, which the PN brought to the clinic to ensure that it was properly uploaded into the EHR.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. We used a patient-level randomization stratified by site; therefore, it is possible that our study design allowed more contamination from the intervention than has been shown in other PC trials. Contamination, if it occurred, may have served to improve care for all patients at the clinic. For this stage of the research, a cluster design was beyond the feasible scope and budget. In addition, we achieved 95.2% (177 of 186) of the target 3-month follow-up sample; therefore, it is possible that there may not have been sufficient power to detect some differences (eg, pain severity and overall QOL). We also did not adjust for multiple primary outcomes.

Conclusions

A culturally tailored PN intervention was highly valued by patients and demonstrated improvement in ACP; however, it had no effect on primary outcomes of pain management and hospice use. Further research is needed to understand the effects and appropriate scope of the PN intervention on a national scale in a cluster design.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Patient Navigator Training and Patient Navigator Intervention

eTable 1. Core Elements of the Patient Navigator Intervention

eTable 2. Process Measures of the Patient Navigator Intervention From the PNPOM

eFigure. Patient Reported Satisfaction With Patient Navigator (n = 87)

References

- 1.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4131-4137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiauzzi E, Black RA, Frayjo K, et al. Health care provider perceptions of pain treatment in Hispanic patients. Pain Pract. 2011;11(3):267-277. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO’s Facts & Figures on Hospice. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care: creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173-1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamal AH, LeBlanc TW, Meier DE. Better palliative care for all: improving the lived experience with cancer. JAMA. 2016;316(1):29-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329-1334. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer SM, Cervantes L, Fink RM, Kutner JS. Apoyo con Cariño: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a patient navigator intervention to improve palliative care outcomes for Latinos with serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(4):657-665. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer SM, Kline DM, Min SJ, Okuyama S, Fink RM. Apoyo con Cariño: strategies to promote recruiting, enrolling, and retaining Latinos in a cancer clinical trial. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(11):1392-1399. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.7005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Barnes DE, et al. An advance directive redesigned to meet the literacy level of most adults: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1-3):165-195. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer SM, Sauaia A, Kutner JS. Patient navigation: a culturally competent strategy to address disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(5):1023-1028. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalal S, Hui D, Nguyen L, et al. Achievement of personalized pain goal in cancer patients referred to a supportive care clinic at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2012;118(15):3869-3877. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):153-158. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Crude death rates. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs/technical_notes/stat_methods/rates.htm. Updated June 4, 2018. Accessed August 9, 2018.

- 19.Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, et al. ; Patient Care Connect Group . Resource use and Medicare costs during lay navigation for geriatric patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):817-825. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammes BJ, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD. A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the prevalence, availability, and specificity of advance care plans in a county that implemented an advance care planning microsystem. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1249-1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Patient Navigator Training and Patient Navigator Intervention

eTable 1. Core Elements of the Patient Navigator Intervention

eTable 2. Process Measures of the Patient Navigator Intervention From the PNPOM

eFigure. Patient Reported Satisfaction With Patient Navigator (n = 87)