Abstract

This study examines recent original research articles in leading oncology journals to evaluate the use of statements about the trend of a P value toward significance to describe statistically nonsignificant results.

The use and interpretation of P values in the biomedical literature is problematic. The importance of a study is often inappropriately defined by the P value. This problem is highlighted by the use of “trend” to refer to statistically nonsignificant results. There is no definition of a trend toward statistical significance and, therefore, describing “almost significant” results as a trend introduces substantial subjectivity and the opportunity for biased reporting language that could mislead a reader (eg, assuming P < .10). To deemphasize P values, some journals prohibit the use of statements about a trend toward significance.1 Instead, presentation and discussion of observed differences and their uncertainty (eg, CIs) are encouraged. The degree of overreliance on P values, and how this overreliance results in unclear reporting practices, is not characterized in the oncology literature, to our knowledge. We examined recent original research articles in oncology journals with high impact factors to evaluate the use of statements about a trend toward significance to describe statistically nonsignificant results.

Methods

Two of us (K.T.N. and M.R.W.) reviewed all original research articles published from November 2016 to October 2017 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI), Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO), JAMA Oncology, and Lancet Oncology to identify instances where describing a trend toward significance was used to describe a statistically nonsignificant result. We focused on this period to describe current practices. We compared the proportion of original research articles with at least 1 statement describing a trend toward significance across journals by comparing percentages and 95% CIs. This project was exempt from approval by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board because it was not human participants research.

Results

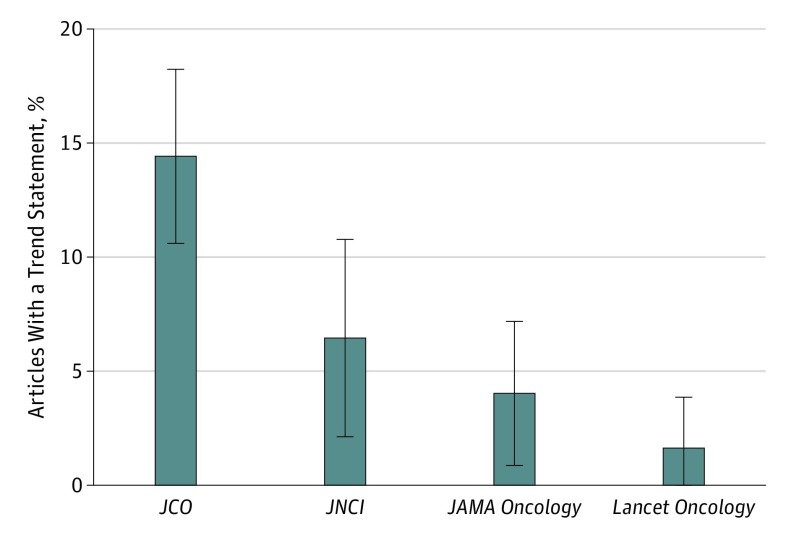

We found that 8.7% (63 of 722) of original research articles in major oncology journals used at least 1 trend statement to describe statistically nonsignificant results. There were notable differences across journals, with 14.4% (47 of 326) of articles in the JCO, 6.5% (8 of 124) of articles in the JNCI, 4.0% (6 of 149) of articles in JAMA Oncology, and 1.6% (2 of 123) of articles in Lancet Oncology using at least 1 statement describing a trend toward significance (Figure). Problematic uses of such statements are described in the Table.2,3,4,5

Figure. Proportion of Original Research Articles Using Trend Statements to Describe 1 or More Statistically Nonsignificant Results From November 2016 Through October 2017.

The error bars indicate 95% CIs. JCO indicates Journal of Clinical Oncology, and JNCI, Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Table. Examples of Problematic Uses of the Word “Trend” to Describe Statistically Nonsignificant Results.

| Text | Trend Statement Location | Comparator Statistics Not Included With Trend Statement (Location in Article) | Point Illustrated |

|---|---|---|---|

| “There was a trend toward long-term survival in favor of GemErlo (estimated survival after 1, 2, and 5 y for GemErlo was 77%, 53%, and 25% vs 79%, 54%, and 20% for Gem, respectively).”2 | Abstract | P = .61 (Figure 2B) | Large P value and trend statement in abstract without supporting comparator statistics |

| “BCL2 expression indicated a trend toward inferior outcome within GCB-like DLBCL, but not within ABC-like DLBCL (Appendix Figure A2, online only).”3 | Results, main text | P = .547 (EFS), P = .351 (PFS), P = .125 (OS) (Appendix) | Large P value and comparator statistics to support trend statement found only in appendix |

| “Women with stage I–II PBL had overall survival superior to women with stage I–II systemic presentations of the same lymphoma subtype (Figure 4), except for ALCL-PBL where the same trend was seen, although not statistically significant at the 5% level.”4 | Results, main text | P = .69 (Figure 4) | Large P value |

| “In unselected patients, a trend for ramucirumab survival benefit was observed in patients with HCC in the Child-Pugh 5 disease subgroup.”5 | Key points section; abstract conclusion | HR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.63-1.02; P = .06 (results text and Figure 1A) | Trend statement highlighted in Key Points section and as primary study conclusion (abstract) without mention of potentially clinically relevant effect size |

Abbreviations: ABC, activated B cell; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; EFS, event-free survival; GCB, germinal center B cell; Gem, gemcitabine; GemErlo, gemcitabine and erlotinib; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; PBL, primary breast lymphoma; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

There were 125 instances where a trend statement was used to describe a statistically nonsignificant result across 63 articles. Eleven statements (8.8%) provided no data by which to evaluate the magnitude of difference between groups (eg, hazard ratio). Of the 86 instances where a P value was presented, 35 (40.7%) were P ≥ .10 (15 [17.4%] were P ≥ .10 to P < .20, 13 [15.1%] were P ≥ .20 to P < .50, and 7 [8.1%] were P ≥ .50).

Discussion

We found that trend statements are frequently used to describe statistically nonsignificant results, commonly with large P values and minimal supporting data. In addition, when P values approached statistical significance, promising clinical significance was often deemphasized to highlight the proximity of the P value to .05. This finding highlights an overemphasis on P values in the reporting of data in the oncology literature.

The biomedical literature currently has a problem with P values. In response to this problem, the American Statistical Association released a statement outlining primary P value principles.6 Among these principles were the following: (1) scientific conclusions should not be based solely on a P value threshold, (2) a P value does not measure the importance of a result, and (3) a P value does not provide a good measure of evidence regarding a hypothesis. Trend statements violate these principles. We must deemphasize P values and shift our focus to the clinical relevance of the finding (eg, the magnitude of the result along with CIs), the power of the study to address a clinically meaningful difference, and the appropriateness of the study design. This shift is additionally important to address the overinterpretation of statistically significant but clinically meaningless findings. As others have proposed, increased methodological and statistical training of scientists and clinicians may enhance the quality of data analysis, reporting, and interpretation. The oncology research community—in particular, leading oncology research journals—should take the lead in implementing the highest standards for reporting of results.

References

- 1.JAMA Oncology, JAMA Network. Instructions for authors. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/pages/instructions-for-authors. Updated August 1, 2018. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- 2.Sinn M, Bahra M, Liersch T, et al. CONKO-005: adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus erlotinib versus gemcitabine alone in patients after r0 resection of pancreatic cancer: a multicenter randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(29):3330-3337. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.6463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staiger AM, Ziepert M, Horn H, et al. ; German High-Grade Lymphoma Study Group . Clinical impact of the cell-of-origin classification and the MYC/ BCL2 dual expresser status in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated within prospective clinical trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2515-2526. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.3660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas A, Link BK, Altekruse S, Romitti PA, Schroeder MC. Primary breast lymphoma in the United States: 1975-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(6). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu AX, Baron AD, Malfertheiner P, et al. Ramucirumab as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of REACH trial results by Child-Pugh Score. JAMA Oncol. 2016;3(2):235-243. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA’s statement on P values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat. 2016;70(2):129-133. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]