Abstract

Purpose:

PI-RADS v2 dictates that dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) imaging be used to further classify peripheral zone (PZ) cases that receive a diffusion weighted imaging equivocal score of 3 (DWI3), a positive DCE resulting in an increase in overall assessment score to a 4, indicative of clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa). However, the accuracy of DCE in predicting csPCa in DWI3 PZ cases is unknown. This study sought to determine the frequency with which DCE changes the PI-RADS v2 DWI3 assessment category, and to determine the overall accuracy of DCE-MRI in equivocal PZ DWI3 lesions.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective study of patients with pathologically-proven PCa who underwent prostate mpMRI at 3T and subsequent radical prostatectomy. PI-RADS v2 assessment categories were determined by a radiologist, aware of a diagnosis of PCa, but blinded to final pathology. csPCa was defined as a Gleason score ≥7 or extra prostatic extension at pathology review. Performance characteristics and diagnostic accuracy of DCE in assigning a csPCa assessment in PZ lesions were calculated.

Results:

A total of 271 men with mean age of 59 ± 6 years mean PSA 6.7ng/ml were included. csPCa was found in 212/271 (78.2%) cases at pathology, 209 of which were localized in the PZ. DCE was necessary to further classify (45/209) of patients who received a score of DWI3. DCE was positive in 29/45 cases, increasing the final PI-RADS v2 assessment category to a category 4, with 16/45 having a negative DCE. When compared with final pathology, DCE was correct in increasing the assessment category in 68.9 ± 7 % (31/45) of DWI3 cases.

Conclusion:

DCE increases the accuracy of detection of csPCa in the majority of PZ lesions that receive an equivocal PI-RADS v2 assessment category using DWI.

Keywords: DCE-MRI, DWI, PI-RADS v2, prostate

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most frequently diagnosed cancer, and the second most frequent cause of cancer death in men in the United States [1,2]. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) is an important tool in the diagnosis and localization of clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa), and plays an increasingly important role in surveillance, risk stratification, and image guidance for prostate biopsy [3–5].

The European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) established the prostate imaging reporting and data system version 1 (PI-RADS v1), a standardized guideline for interpretation and reporting prostate mpMRI for the purpose of harmonizing mpMRI use [6,7]. Multiple studies evaluated the value and accuracy of PI-RADS v1, but it was determined that the use of MR spectroscopy and DCE sequences may not add significant value to the interpretation of mpMRI and subsequently, PI-RADS version 2 (PI-RADS v2) was introduced [8–11]. PI-RADS v2 is designed to improve detection, localization, characterization, and risk stratification in patients with suspected cancer in treatment naïve prostate glands. The overall objective is to improve outcomes for patients [10]. With PI-RADS v2, lesions receive an assessment category of 1–5, with higher scores (4 and 5) associated with a higher likelihood of csPCa [12].

Specific to the peripheral zone (PZ), where the vast majority of PCa occurs, diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) determines the final assessment category, irrespective the T2-weighted category. However, a DWI score of 3 (DWI3) denotes an overall assessment category of 3, which is equivocal for csPCa [13–15]. In this situation, a positive DCE, defined as enhancement that is “focal, and earlier than or contemporaneously with enhancement of adjacent normal prostatic tissues, and corresponds to suspicious finding on DWI and/or T2-weighted images”, can increase the likelihood that the lesion represents csPCa, and will upgrade the final assessment category to a PI-RADS v2 4 [11]. The importance of this secondary role is underscored by the fact that between 13–23% of PZ lesions have been reported as equivocal on recent studies [16,17].

Although DCE may be helpful in equivocal cases, there are potential drawbacks to performing DCE, namely it requires intravenous administration of gadolinium, with higher financial costs and longer scanning time, and increases the risk of gadolinium accumulation in multiple organs such as renal glomeruli, brain, and bones with possible clinical sequelae [18–21].

Considering the above risks and benefits of DCE, the goal of this study is to determine the frequency with which DCE changes the final PI-RADS v2 assessment category in DWI3 PZ lesions, and to determine the accuracy of DCE-MRI in correctly up-grading PI-RADS v2 assessment category to that of csPCa.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) compliant retrospective study used a Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR) to identify all treatment-naive male patients at our institution who had endorectal coil mpMRI at 3T between January 2011-January 2015, and pathology-proven PCa within 6 months of undergoing mpMRI. Only those who subsequently underwent radical prostatectomy were included in the study. Demographic and clinical information were obtained from the electronic medical record (EMR) system.

Multi parametric MRI Protocol

All the scans were performed with a 3 T magnet (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using an endorectal coil and 8-channel abdominal array. Gadopentetate dimeglumine (Berlex Laboratories, Wayne, NJ) was injected into a peripheral vein (0.15 mmol/kg; rate 3ml/sec) followed by a 20 ml saline flush. Spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) T1-weighted sequences with repetition time (TR) 385 ms, echo time (TE) 6.2 ms and α 65°. T2-weighted (T2W) sequences were acquired using fast spin echo, repetition time (TR) 3500 ms and echo time (TE) 102 ms. The field of view (FOV) was >16 cm2 and the in-phase dimension was < 0.7 × 0.4 mm (phase × frequency). DWI sequences were performed on a free breathing spin echo and spectral fat saturation with TR 2500 ms, TE 65 ms for b value 0,500 and TR 3000 ms, TE 80 ms for b value 0,1400 s/mm2. In addition, 3D SPGR DCE sequences were performed using 3D gradient echo with TR 3.6 ms, TE 1.3 ms, α ° 15 FOV = 26×26 cm2 including the entire prostate gland and seminal vesicles, with temporal resolution of 5 s, and total observation time of 5 minutes, as described previously [22]. Subtracted DCE images were generated. MRI was obtained more than 50 days after biopsy to minimize post-biopsy changes.

MRI Evaluation

De-identified mpMRIs of each patient were analyzed using 3D Slicer, an open source image processing software (www.slicer.org) [23]. The location of suspected lesions on the prostate gland, the PI-RADS v2 assessment category for individual sequence (DWI, T2W, DCE), and the overall PI-RADS v2 assessment category were recorded by a radiologist with 14 years of experience in prostate MRI who was aware of a PCa diagnosis for all cases but blinded to final pathology, including the Gleason score. The maximum length, width, and height of the suspected lesion on ADC sequence were measured and the lesion volume was calculated using the “0.5 × W × L × H” formula. In cases lesion measurement was difficult or compromised on ADC for PZ or T2W for transitional zone (TZ), measurement was made on the sequence that shows the lesion best.

Reference Standard

The radical prostatectomy pathology report was used as the reference standard. csPCa was defined as a Gleason score ≥7 [24]. The index lesion on MRI was correlated with location based on zonal anatomy, as described previously [25].

Statistical Analysis

The rate of false positive, false negative, true positive and true negative PI-RADS v2 assessment categories and DCE MRI results were recorded in to a 2×2 table using radical prostatectomy pathology result as the reference standard. Performance characteristics of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV), and diagnostic accuracy of PI-RADS v2 assessment categories and DCE imaging were calculated. The Chi-Square test was used to measure the effect of lesion size. The statistical tests were performed using the SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) software. For tests of all variables, P <0.05 signified statistical significance.

Results

Clinical findings

A total of 271 men with mean age of 59 ± 6 years, 230/271 (84.9%) of whom were Caucasian were included in the study. 217/271 (80%) had stage 2 PCa. The range of PSA level measured before the MRI scan was 0.01–38.77ng/ml with a mean 6.7 ± 4.7 ng/ml. At radical prostatectomy, csPCa was found in 212/271 (78.2%) patients.

In 247 (91.1%) scans the dominant lesion, based on lesions size and PI-RADS assessment category, was selected for analysis. No suspicious lesion was detected on remaining 24/271 (8.9%) MRI scans. Of these 247 scans, 209 (84.6%) dominant lesions were localized in PZ, 31 (12.6%) in TZ, four (1.6%) in central zone (CZ), three (1.2%) in the anterior segment (AS). Table 1 presents the demographic and PCa features of all patients included in the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all 271 patients included in the study

| Characteristics | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD age | 59±6 y | - |

| Race | White | 230 (84.9) |

| African American |

22 (8.1) | |

| Hispanic | 10 (3.7) | |

| Other | 9 (3.3) | |

| PSA | <4 | 51 (18.8) |

| 4–10 | 173 (63.8) | |

| ≥10 | 39 (14.4) | |

| Unknown | 8 (3) | |

| Location of suspicious lesion | PZ | 209 (77.1) |

| TZ | 31 (11.4) | |

| CZ | 4 (1.5) | |

| AS | 3 (1.1) | |

| No lesion | 24 (8.9) | |

| Pathological AJCC Stage | 1 | 8 (3) |

| 2 | 217 (80) | |

| 3 | 45 (16.6) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.4) | |

| <7 | 60 (22.1) | |

| Gleason score on prostatectomy | ≥7 | 211 (77.9) |

| MRI based Volume (cc) | ≤0.5 | 113 (41.7) |

| >0.5 | 134 (49.4) | |

| N/A | 24 (8.9) | |

| csPCa | Yes | 212(78.2) |

| No | 59 (21.8) | |

PSA: Prostate Specific Antigen, csPCa: Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer, PZ: Peripheral Zone, TZ: Transitional Zone, CZ: Central Zone, AS: Anterior Segment

Overall performance of PI-RADS v2

Multiparametric MRI were read as negative for any suspicious lesion in 8.9% (24/271) scans. Of these, radical prostatectomy pathology reports showed 15/24 (62.5%) true negative (non-csPCa) and nine (37.5%) false negative results for csPCa. In the remaining 247 (91.1%) scans, at least one suspicious lesion was reported. Table 2 presents mpMRI results based on PIRADS v2 assessment category compared to radical prostatectomy pathology findings. When the PI-RADS v2 assessment category results were compared to the radical prostatectomy pathology results, 189/271 (69.7%) cases were true positive and 25/271 (9.2%) cases false positive; 34 (12.6%) cases were true negative and 23 (8.5%) cases false negative for csPCa, yielding a sensitivity of 89.2%, a specificity of 57.6%, a PPV of 88.3%, a NPV of 59.6% and diagnostic accuracy of 82.3% in detecting csPCa.

Table 2.

Performance by assessment category of PI-RADS v2 in detection of csPCa

| PI-RADS v2 results | Number | csPCa + (%) | csPCa – (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No suspicious lesion | 24 | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5%) |

| Assessment category 2 | 9 | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) |

| Assessment category 3 | 24 | 8 (33.3) | 16 (66.7) |

| Assessment category 4 | 131 | 109 (83.2) | 22 (16.8) |

| Assessment category 5 | 83 | 80 (96.4) | 3 (3.6) |

RP: Radical Prostatectomy, csPCa: Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer

Lesion size and MRI detection rate

Of 212 patients with csPCa, 122 (57.5%) had a dominant lesion with an MR-based volume of >0.5 cc. Of these, one (0.8%) mpMRI was read as assessment category 2, one (0.8%) as assessment category 3, 43 (35.3%) as assessment category 4, and 77 (63.1%) as assessment category 5. Among the remaining 90/212 (42.5%) cases with csPCa, no lesion was found in 9 (10%) cases and 81 (90%) cases had a dominant lesion with MR-based volume of ≤0.5 cc; which five (5.6%) mpMRI were read as assessment category 2, seven (7.8%) as assessment category 3, 6 6 (73.3%) as assessment category 4, and three (3.3%) as assessment category 5. Therefore, 120/122 (98.4%) of lesions >0.5 cc and 69/90 (76.7%) of lesions ≤0.5 were categorized correctly for csPCa by PI-RADS v2 (p<0.001).

Performance of DCE in PI-RADS v2

To determine how often DCE changes the PI-RADS v2 assessment category and the accuracy of such changes, all cases with the peripheral lesion and DWI3 were selected. Among 209 scans with a dominant PZ lesion, 45/209 (21.5%) scans had a DWI3; therefore, PI-RADS v2 assessment category in this group was impacted by DCE findings in 21.5% (45/209) of patients with PZ lesion. In those 45 (21.5%) cases, DCE was positive in 29/45 (64.4%) and negative in 16/45 (35.6%) cases (Figs. 1,2). Comparison of DCE findings with the radical prostatectomy pathology demonstrated that 21/45 (46.6%) were a true positive and eight (17.8%) cases were a false positive. Among patients with negative DCE, 10/45 (22.2%) cases were a true negative and six (13.4%) cases were a false negative. The estimated odds ratio for the relationship between DCE and RP was 4.38 (SE ±1.55) (95% confidence interval is 1.85, 10.33). DCE is significantly associated with RP in these equivocal cases (X2=3.9, P=0.03 based on a chi-square test with simulated p-value). Table 3 shows the sensitivity (77.8%), specificity (55.6%), PPV (72.4%), NPV (62.5%) and diagnostic accuracy of DCE (68.9%) in detecting csPCa among equivocal cases.

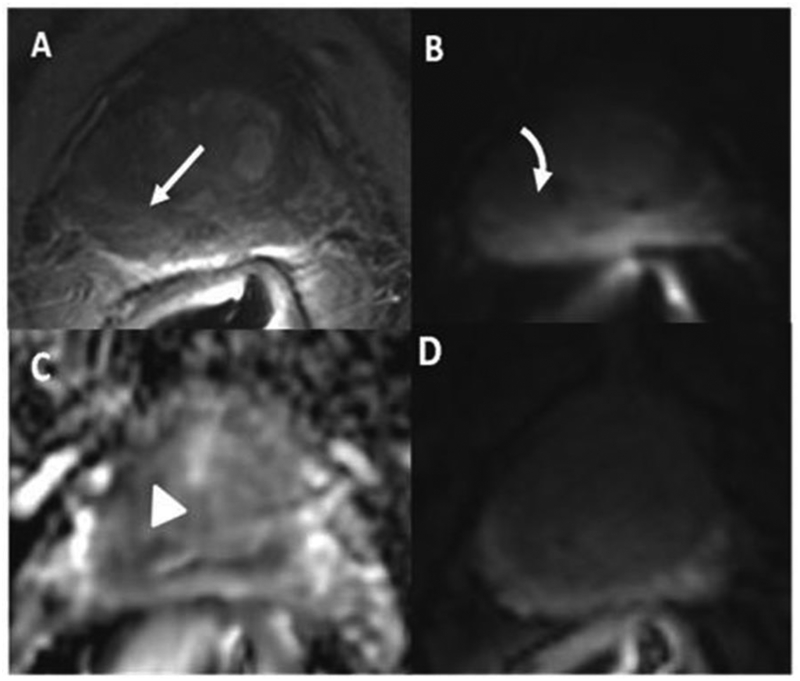

Fig. 1.

A 68-year-old man with PSA of 4 ng/ml. Transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy which showed Gleason Score 3+3 in 6/12 cores. (A) T2 weighted image shows a mildly hypointense lesion in the right peripheral zone (arrow), corresponding to a minimally hyperintense area on diffusion weighted image (DWI) (curved arrow) (B). The lesion is mildly hypointense on ADC (C) map (arrowhead) with diffuse enhancement on DCE (D) (dashed arrow). PI-RADS v2 assessment was category 3 in T2 and DWI and negative DCE indicating overall PI-RADS category 3. Radical prostatectomy showed a Gleason score 3+3 peripheral zone prostate cancer.

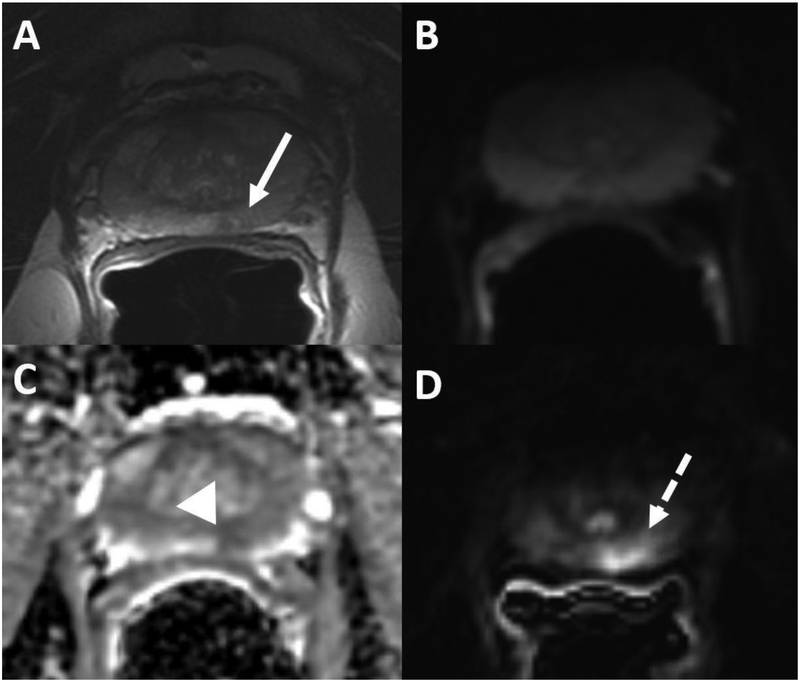

Fig. 2.

54-year-oldman PSA of 2.9 ng/ml. (A) T2 weighted image shows a mildly hypointense lesion in the left peripheral zone (arrow), which is isointense on diffusion weighted image (DWI) (B). The lesion is mildly hypointense on ADC map (arrowhead) (C) with early enhancement on subtracted on DCE (dashed arrow) (D). PI-RADS v2 assessment was category 3 on DWI and T2 weighted image and positive DCE demonstrating overall PI-RADS category 4. Radical prostatectomy was performed and showed a Gleason score 3+4 peripheral zone prostate cancer.

Table 3.

The value of DCE in equivocal PZ lesions

| TP | FP | TN | FN | Total | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCE-MRI in PZ lesions with DWI3 | 21 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 45 | 77.8% | 55.6% | 72.4% | 62.5% | 68.9% |

TP: True Positive, FP: False Positive, TN: True Negative, FN: False Negative, PPV: Positive Predictive Value, NPV: Negative Predictive Value, PZ: Peripheral Zone

Among those 27/45 (60%) cases who had csPCa in RP, 12/27 (44.4%) patients had a dominant lesion with an MR-based volume of >0.5 cc. One scan (8.3%) was read as negative DCE and 11 (91.7%) other scans were read as positive DCE. The remaining 15/27 (55.6%) cases with csPCa, had a dominant lesion with MR- based volume of ≤0.5 cc; DCE was read positive in 10/15 (66.7%) scans and negative in 5 (33.3%) scans. Eleven of twelve (91.7%) > 0.5 cc lesion and 10/15 (66.7%) ≤0.5 lesions were categorized correctly as csPCa by PI-RADS v2 (p>0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the performance of PI-RADS v2 and the role of DCE sequence in detecting csPCa, using pathology from radical prostatectomy as the reference standard. In our study, the diagnostic accuracy of PI-RADS v2 assessment for csPCa detection compared to the radical prostatectomy pathology results, was 83.2%, similar to the results the reported in a recent meta-analysis evaluating accuracy of PI-RADS v2 for PCa detection where reported area under the curve was 0.86 [26].

DCE assessment impacted PI-RADS v2 assessment category in 21.5 % (45/209) of cases with PZ lesion, increasing the assessment category to 4 in 77.8% (21/27) and keeping it unchanged in 55.6% (10/18) of cases. DCE was correct in increasing the assessment category to that of csPCa in 68.9% (31/45) of equivocal PZ lesions.

A recently published study by De Visschere et al. evaluated the role of DCE in a mixed PCa population which included patients who had undergone RP, radiation therapy, and were on active surveillance [27]. Histopathology gold standard was based on RP specimen or transrectal ultrasonography-guided biopsy (TRUSgBX) specimen as the standard of reference. Considering the differences in methodology between this study and ours, overall DCE performances were similar. De Visschere et al. reported that DCE was used in 19.2% of the patients and DCE findings were correct in approximately 70% of the cases [27]. Our population was more homogenous with prostatectomy pathology used as the gold standard. The difference in patient population and difference in reference pathology is an important distinction, especially when we consider that pathology based upon prostate biopsy (trans-rectal or trans-perineal) has been shown to incorrectly report Gleason score 6 in approximately 50% of patients with a Gleason score 7 on subsequent radical prostatectomy [28,29].

For many reasons, there has been a recommendation to use biparametric MRI (biMRI; DWI and T2 sequences) instead of entire mpMRI sequences in assessing PCa. Two separate studies, Thestrup et al. and De Visschere et al. claimed that biMRI was comparable to mpMRI in detecting csPCa [27,30]. mpMRI however, provides more than focal lesion assessment, for staging purposes (seminal vesicle involvement, lymph node involvement and extra prostatic extension), therapy response assessment, and for detection of PCa recurrence (post-surgery and radiation therapy) [31–35]. A possible approach could be reserving DCE for initial lesion assessment and only in those patients who receive a DWI3 of an index PZ lesion. This method could decrease the costs of MRI, scanning time, and contrast related side effects. However, it would require a real-time onsite evaluation of images by an expert radiologist [27,34]. Larger studies are required to assess the cost-benefit of this approach.

Radiologist experience in PI-RADS v2 assessment and the overall size of the suspicious lesion are also important factors to be considered when discussing the accuracy of the assessment category [37]. According to Vargas et al., pathologic PCa volume was reported to have a great impact on detection of csPCa on mpMRI using PI-RADS v2 [36]. In our study, csPCa was detected correctly using PI-RADS v2 in 92.5% of lesions with MR volume>0.5 cc versus 77.8% of lesions with volume ≤0.5 cc. Vargas et al. demonstrated that 95% of large size tumors were detected by PI-RADS v2 with only 20–26% of small size lesions detected on mpMRI using PI-RADS v2 [36]. Although in the present study the lesion size was measured on MRI (not pathology based), the impact of lesion volume is comparable, especially in lesions with a volume >0.5cc [38].

Our findings are also supported by a recent study by Druskin et al. where DCE did identify a higher-risk group of DWI3 PZ lesions. They reported that DWI3 PZ lesions with DCE-positivity on mpMRI had a higher grade on biopsy than those with DCE-negativity, which is similar to our findings [39].

There are some limitations to our study. Our clinical data was collected retrospectively through electronic medical record review, with the possibility of inherent biases associated with retrospective study design. Patients who did not undergo radical prostatectomy were excluded, which could be considered a selection bias. We also did not do whole mount processing of the prostatectomy specimen to allow for more precise anatomical correlation with the MR images, nonetheless we marked the index lesion on MRI and correlated with location of lesion on pathology report. In addition, we did not evaluate inter-reader agreement for DWI and DCE. inter-reader agreement. However, a recent study evaluated inter-reader agreement of PIRADS v2 for detection of GP≥3+4 PCa, showed good agreement for lesions with PI-RADS assessment category ≥3 [40].

In summary, qualitative DCE MRI identifies csPCa in the majority of equivocal PZ lesions. These results should be taken into consideration when a reduced time screening MRI for detection of nascent PCa.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Grant funding provided by U01CA151261 (FMF), P41 EB015898 (CT, FMF) and DPH403516 (FMF, CT) and R25CA89017 (FMF, AZ).

Funding: National Institute of Health - National Cancer Institute: U01 CA151261; R25 CA089017; NIH P41EB 015898; Massachusetts Department of Public Health: DPH 403516.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Mehdi Taghipour declares he has no conflict of interest.

Alireza Ziaei declares he has no conflict of interest.

Elmira Hassanzadeh declares he has no conflict of interest.

Francesco Alessandrino declares he has no conflict of interest.

Mukesh Harisinghani, declares he has no conflict of interest.

Mark Vangel declares he has no conflict of interest.

Clare M Tempany received the grant NIH P41 EB015898 from National Institute of Health - National Cancer Institute, and the grant DPH 403516 from Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Fiona M Fennessy received the grants from Institute of Health - National Cancer Institute: U01 CA151261; R25 CA089017

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent: For this type of study formal consent is not required.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016; Available from: www.cancer.org, accessed September 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassanzadeh E, Glazer DI, Dunne RM, Fennessy FM, Harisinghani MG, Tempany CM (2017) Prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2 (PI-RADS v2): a pictorial review. Abdom Radiol 42(1):278–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turkbey B, Brown AM, Sankineni S, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL (2016) Multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of prostate cancer. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 66(4):326–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penzkofer T, Tuncali K, Fedorov A, et al. (2014) Transperineal in-bore 3-T MR imaging guided prostate biopsy: a prospective clinical observational study. Radiology 274(1):170–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fennessy FM, Tuncali K, Morrison PR, Tempany CM (2010) Mr imaging-guided interventions in the genitourinary tract: An evolving concept. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics 18(1):11–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, et al. (2012) ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. European radiology 22(4):746–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bomers JG, Barentsz JO (2014) Standardization of multiparametric prostate MR imaging using PI-RADS. BioMed research international. DOI: 10.1155/2014/431680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansford BG, Peng Y, Jiang Y, et al. (2015) Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging curve-type analysis: is it helpful in the differentiation of prostate cancer from healthy peripheral zone? Radiology 275(2):448–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Platzek I, Borkowetz A, Toma M, et al. (2015) Multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging at 3 T: failure of magnetic resonance spectroscopy to provide added value. J Comput Assist Tomogr 39(5):674–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan CH, Paul Hobbs B, Wei W, Kundra V (2015) Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for the detection of prostate cancer: meta-analysis. Am J Roentgenol 204(4): W439–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, et al. (2016) PI-RADS prostate imaging-reporting and data system: 2015, version 2. Eur Urol 69(1):16–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Druskin SC, Ward R, Purysko AS, et al. (2017) Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging improves classification of prostate lesions: a study of pathological outcomes on targeted prostate biopsy. J Urol 198(6):1301–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenkrantz AB, Verma S, Turkbey B (2015) Prostate cancer: top places where tumors hide on multiparametric MRI. Am J Roentgenol 204(4):W449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrett T, Turkbey B, Choyke PL (2015) PI-RADS version 2: what you need to know. Clin Radiol 70(11):1165–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tewes S, Mokov N, Hartung D, et al. (2016) Standardized reporting of prostate MRI: comparison of the prostate imaging reporting and data system (PI-RADS) version 1 and version 2. PloS One 11(9): e0162879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenkrantz AB, Babb JS, Taneja SS, Ream JM (2016) Proposed adjustments to PIRADS version 2 decision rules: impact on prostate cancer detection. Radiology 283(1):119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenkrantz AB, Ginocchio LA, Cornfeld D, et al. (2016) Interobserver reproducibility of the PI-RADS version 2 lexicon: a multicenter study of six experienced prostate radiologists. Radiology 280(3):793–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zobel BB, Quattrocchi CC, Errante Y, Grasso RF (2016) Gadolinium-based contrast agents: did we miss something in the last 25 years? Radiol Med 121(6):478–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Idée JM, Fretellier N, Robic C, Corot C (2014) The role of gadolinium chelates in the mechanism of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a critical update. Crit Revs in Toxicol 44(10):895–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darrah TH, Prutsman-Pfeiffer JJ, Poreda RJ, Campbell ME, Hauschka PV, Hannigan RE (2009) Incorporation of excess gadolinium into human bone from medical contrast agents. Metallomics 1(6):479–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. (2015) Intracranial gadolinium deposition after contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 275(3):772–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fennessy FM, Fedorov A, Penzkofer T, et al. (2015) Quantitative pharmacokinetic analysis of prostate cancer DCE-MRI at 3 T: comparison of two arterial input functions on cancer detection with digitized whole mount histopathological validation. Magn Reson Imaging 33(7):886–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. (2012) 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. M Magn Reson Imaging 30(9):1323–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, et al. (2018) MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2018;378(19):1767–1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedorov A, Penzkofer T, Hirsch MS, et al. (2015) The role of pathology correlation approach in prostate cancer index lesion detection and quantitative analysis with multiparametric MRI. Acad Radiol 22(5):548–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Tang M, Chen S, Lei X, Zhang X, Huan Y (2017) A meta-analysis of use of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2 (PI-RADS V2) with multiparametric MR imaging for the detection of prostate cancer. Eur Radiol 27(12):5204–5214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Visschere PI, Lumen N, Ost P, Decaestecker K, Pattyn E, Villeirs G (2017) Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging has limited added value over T2-weighted imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging when using PI-RADSv2 for diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer in patients with elevated PSA. Clin Radiol 72(1):23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein JI, Feng Z, Trock BJ, Pierorazio PM (2012) Upgrading and downgrading of prostate cancer from biopsy to radical prostatectomy: incidence and predictive factors using the modified Gleason grading system and factoring in tertiary grades. Eur Urol 61(5):1019–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Elia C, Cerruto MA, Cioffi A, Novella G, Cavalleri S, Artibani W (2014) Upgrading and upstaging in prostate cancer: From prostate biopsy to radical prostatectomy. Mol Clin Oncol 2(6):1145–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thestrup KC, Logager V, Baslev I, Moller JM, Hansen RH, Thomsen HS (2016) Biparametric versus multiparametric MRI in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Acta Radiol Open 5(8):2058460116663046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fusco R, Sansone M, Petrillo M, et al. (2016) Multiparametric MRI for prostate cancer detection: Preliminary results on quantitative analysis of dynamic contrast enhanced imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging and spectroscopy imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 34(7):839–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dinh CV, Steenbergen P, Ghobadi G, et al. (2016) Magnetic resonance imaging for prostate cancer radiotherapy. Phys Med 32(3):446–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett T, Gill AB, Kataoka MY, et al. (2012) DCE and DW MRI in monitoring response to androgen deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer: a feasibility study. Magn Reson Med 67(3):778–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panebianco V, Barchetti F, Grompone MD, et al. (2016) Magnetic resonance imaging for localization of prostate cancer in the setting of biochemical recurrence. Urol Oncol 34(7):303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lista F, Gimbernat H, Cáceres F, Rodríguez-Barbero JM, Castillo E, Angulo JC (2014) Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of extracapsular invasion and other staging parameters in patients with prostate cancer candidates for radical prostatectomy. Actas Urol Esp 38(5):290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vargas HA, Hötker AM, Goldman DA, et al. (2016) Updated prostate imaging reporting and data system (PIRADS v2) recommendations for the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer using multiparametric MRI: critical evaluation using whole-mount pathology as standard of reference. Eur Radiol 26(6):1606–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasel-Seibert M, Lehmann T, Aschenbach R, et al. (2016) Assessment of PI-RADS v2 for the detection of prostate cancer. Eur J Radiol 85(4):726–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bratan F, Melodelima C, Souchon R, et al. (2014) How accurate is multiparametric MR imaging in evaluation of prostate cancer volume? Radiology 275(1):144–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Druskin SC, Ward R, Purysko AS, Young A, Tosoian JJ, Ghabili K, Andreas D, Klein E, Ross AE, Macura KJ (2017) Dynamic Contrast Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging Improves Classification of Prostate Lesions: A Study of Pathological Outcomes on Targeted Prostate Biopsy. J Urol 198(6):1301–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purysko AS, Bittencourt LK, Bullen JA, et al. (2017) Accuracy and interobserver agreement for prostate imaging reporting and data system, version 2, for the characterization of lesions identified on multiparametric MRI of the prostate. Am J Roentgenol 209(2):339–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]