Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate trends and factors associated with mode of delivery in the rural Southwest Trifinio region of Guatemala.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective analysis of self-reported antepartum factors and postpartum outcomes recorded in a quality improvement database among 430 women enrolled in a home-based maternal healthcare program between June 1, 2015 and August 1, 2017.

Results:

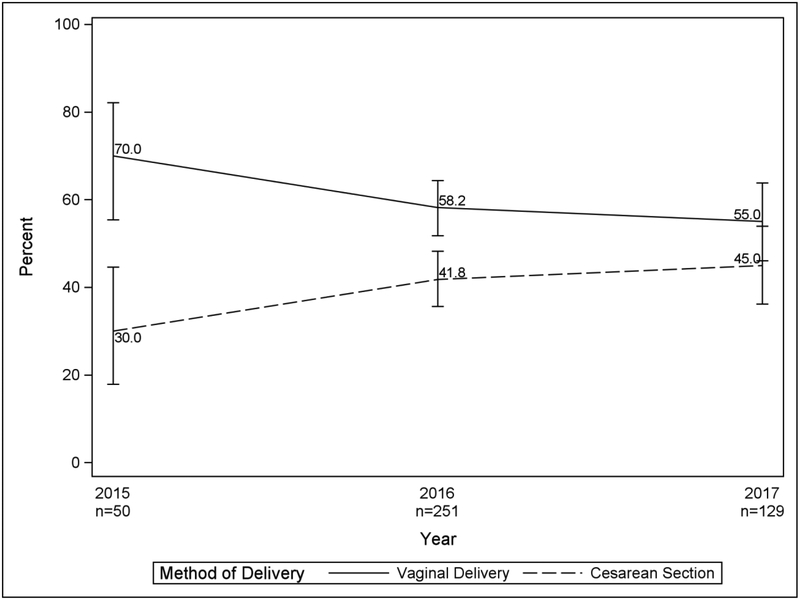

Over the study period, the rates of cesarean delivery (CD) increased (from 30% to 45%) and rates of vaginal delivery (VD) decreased (70% to 55%) while facility-based delivery attendance remained stable around 70%. Younger age (23.5 years for VD versus 21.6 years for CD, p < 0.001), nulliparity (25.1% for VD versus 45.0% for CD, p < 0.001), prolonged/obstructed labor (2.4% for VD versus 55.6% for CD, p < 0.001), and fetal malpresentation (0% for VD versus 16.3% CD, p < 0.001) significantly influenced mode of delivery in univariate analysis. The leading indications for CD were labor dysfunction (47.5%), malpresentation (14.5%), and prior cesarean delivery (19.8%). The CD rate among the subpopulation of term, nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies in vertex presentation also increased from 20% of all CD in 2015, to 38% in 2017.

Conclusions:

Among low-income women from rural Guatemala, the CD rate has increased above the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations in a period of 3 years. Additional research on the factors affecting this trend are essential to guide interventions that might improve the appropriateness of CD, and to determine if reducing or stabilizing rates is necessary.

Keywords: vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, nulliparous term singleton vertex, Guatemala, pregnancy

Introduction

Cesarean Delivery (CD) rates have risen significantly in Latin America and globally (Villar 2006, Betran 2016). The impact of increasing rates on maternal and perinatal outcomes is unclear. An analysis of the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in eight Latin American countries showed that increasing CD rate was significantly associated with severe maternal morbidity and mortality, increases in fetal mortality and admission to the intensive care unit.1 In Peru, a study of over 500,000 deliveries found that with an increasing CD rate, stillbirths were reduced, but the rates of preterm birth, delivery of multiples, and delivery for pre-eclampsia were higher in the CD group (Gonzales 2013). Maternal mortality in the CD group was 5.5 times higher than for women undergoing vaginal delivery (Gonzales 2013). Similarly, a more recent study from six low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), that included Guatemala, found that in the non-African sites, maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage and obstetric interventions and treatments, were more common in women who underwent CD despite positive reductions in postpartum hemorrhage and stillbirth (Harrison 2017).

For women cared for in the public sector in Brazil, age (> 20 years), primiparity, multiple gestation, private prenatal care, attendance at greater than six visits, and delivery at a high-risk hospital setting were associated with CD (at a rate of 29.9%) (Vieira 2015). For the women cared for in the private sector, the CD rate was 86.2% and no specific associations were found to determine this substantially higher rate (Vieira 2015). This analysis did not comment on the relationship of CD to pregnancy outcomes, but this drastic difference in rates between the public and private sector suggests adverse payment incentives (Hopkins 2014). The World Health Organization (WHO) has implied that because of the cost associated with surgical delivery, CD may be an impediment to universal coverage of maternal health services globally, due to the unnecessary CD, that account for a disproportionate share of resources (Gibbons 2010).

With respect to Guatemala, the overall cesarean section rate is increasing similar to global trends (Betran 2016). The UNICEF State of the World’s Children report from 2009–2013 reports an overall country-wide cesarean section rate of 16.3% (SOWC 2013). The rate increased to 26.3% as published in the Guatemalan Demographic and Health Survey from 2014–2015, which is the most recent data available (DHS 2014 – 2015). These rising rates of CD occurring globally and regionally can have dramatic implications for the health of women, their fetuses and infants, and adversely impact the health systems of low and middle-income countries (LMIC). A meta-analysis evaluating the outcomes of CD in LMIC is underway to try and provide insight into some of these issues (Beogo 2017). Similarly, we sought to investigate the trends and impact of CD in remote rural communities like the Southwest Trifinio region of Guatemala as a first step in assessing the needs and strategies to improve maternal-neonatal outcomes in non-urban communities.

Methods:

Background:

In 2011, the Center for Global Health (CGH) from the University of Colorado, in partnership with the local agribusiness corporation Agroamerica, created the Center for Human Development to improve the livelihoods and health of the population from the southwest Trifinio area in the lowlands of Guatemala. These 22 communities have high rates of poverty, food insecurity, poor access to health care and safe water, and as a consequence have high rates of maternal complications and neonatal mortality (Asturias 2016). In 2012, a community-based pregnancy and neonatal clinical and administrative quality-improvement database was established with the aims of providing improved home-based prenatal and postpartum care to women and ensure early detection of women and neonates at risk with the ultimate goal of decreasing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality (Asturias 2016).

Design and population:

This study is a restrospective analysis of prospectively collected clinical and administrative quality improvement data from the Madres Sanas (MS) program. The database belongs to the Center for Human Development of the Fundacion para la Salud Integral de los Guatemaltecos (FUNSALUD) and it utilizes RedCAP at a secure e-health platform of the CGH. 9,10 The primary purpose of the data collection in the MS program is to assess program efficacy in improving pregnancy outcomes (Asturias 2016). Women are recruited into MS from 12 of the 22 communities by other community members, local leaders, community outreach nurses, and the local health clinic (Asturias 2016). We estimate about 30% of women from the nearby 12 communities were enrolled in the program.

Data Collection:

Trained MS nurses collected the demographic and health information from pregnant women and their neonates (details on antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care, neonatal and maternal outcomes, breastfeeding, and family planning) via mobile phone app-based questionnaires (Asturias 2016). Of note, gestational age was determined by patient-reported estimated due date at the earliest time point in pregnancy.

Data Analysis:

We compared method of delivery with the Pearson’s chi-squared test for nominal categorical variables unless there was low cell size, in which case the Fisher’s exact test was used. We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare ordinal variables and the t-test for continuous variables. Because the proportion of c-sections was common (41.%) we used Poisson regression with a robust error variance to test differences in method of delivery between year of delivery (categorical) for unadjusted and adjusted results. To observe whether there was a trend over time in the change of cesarean rates we tested the data three ways: 1) we observed year (by months) as a linear variable, 2) we observed year (by months) before June, 2016 versus after as suggested by LOESS modeling, and 3) as a categorial variable by year. Year as a categorical variable was the best model fit as measured by the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The model was adjusted for age (continuous), parity (categorical 0, 1, 2, 3+) and any antepartum condition. None of the interactions of year by the adjusting variable were statistically significant at the 0.2 level and were dropped from the model. Poisson regression was also used to model the association of method of delivery and antepartum risk factors with method of delivery adjusted for age, parity and year of delivery. We considered a p-value of < 0.05 statistically significant. All analyses were performed on SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA).

Results:

The Figure 1 CONSORT diagram illustrates the women selected for the analysis. Of the 663 women enrolled in the program after June 1, 2015, we included 430 (74%), and 233 were excluded for reasons of not having a follow up postpartum visit (where pregnancy outcomes data is obtained) because they had not yet reached their estimated due date, or the data was not recorded. A comparison of the 233 women with missing data to the 430 women included in the analysis showed the two groups did not differ significantly on any demographic characteristics including: age, marital status, education level, parity, and history of a prior cesarean section (data not shown).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of Women from the SW Trifinio Included and Excluded from the Analysis

Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of women undergoing VD compared to CD in the SW Trifinio region of Guatemala over the 3-years of observation. When compared on basic demographic characteristics, the groups were significantly different in terms of average age and parity; women undergoing CD were younger and more likely to be nulliparous. The two groups also differed by site of birth and birth attendant. Women undergoing CD were more likely to deliver in a large public hospital (79%) or small private hospital (21%) whereas women who experienced vaginal delivery more commonly delivered at the home of the patients’ mother (45.6%) or a large public hospital (42.4%, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women Undergoing Vaginal Compared to Cesarean Delivery in the SW Trifinio Region of Guatemala, 2015 – 2017.

| Total n = 430 | Vaginal Delivery (n=252, 58.6%) | Cesarean Delivery (n=178, 41.4%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD)) | 23.5 (6.3) | 21.6 (5.1) | <0.001a |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Married/Living with a Partner | 232 (92.0%)? | 162 (91.0%) | 0.70b |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Education | |||

| No formal education | 91 (36.1%) | 57 (32.2%) | 0.31b |

| Elementary School | 116 (46.0%) | 78 (44.1%) | |

| High School | 45 (17.9%) | 42 (23.7%) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | |

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 61 (25.1%) | 76 (45.0%) | <0.001c |

| 1 | 60 (24.7%) | 53 (31.4%) | |

| 2 | 59 (24.3%) | 23 (13.6%) | |

| 3+ | 63 (25.9%) | 17 (10.1%) | |

| Missing | 9 | 9 | |

| Gestational Age at Birth | |||

| < 34 | 8 (3.5%) | 3 (1.7%) | 0.50c |

| 34 – 36+6 | 22 (9.7%) | 15 (8,6%) | |

| 37 – 38+6 | 63 (27.8%) | 54 (30.9%) | |

| ≥39 | 134 (59.0%) | 103 (58.9%) | |

| Missing | 25 | 2 | |

| Location of Birth | |||

| Large Public Hospital | 107 (42.4%) | 140 (79%) | <0.001d |

| Small private hospital | 17 (6.7%) | 38 (21%) | |

| Home of a Nurse Midwife | 5 (2.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Home of the Patient’s Mother | 115 (45.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Center for Human | 8 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Development | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing | |||

| Birth Attendant | |||

| Doctor | 122 (48.4%) | 178 (100%) | <0.001d |

| Nurse | 7 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Traditional Birth Attendant | 117 (46.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Family | 6 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

Number (percent) unless otherwise specified.

T-test

Chi-square test

Wilcoxon rank sum test

Fisher’s exact test

Births by CD were all delivered by a doctor while VD were attended both by physicians and traditional birth attendants. Figure 2 displays how the rate of CD changed in the community over time. This difference was statistically significant after adjusting for age, parity, and any antepartum condition between 2015 and 2016 (p = 0.006), and 2015 and 2017 (p = 0.043), but not between 2016 and 2017 (p = 0.0.071).

Figure 2.

Trends in Method of Delivery in the SW Trifinio Region of Guatemala, 2015 – 2017. Unadjusted percents and 95% confidence intervals.

The proportion of CD performed for various indications (prolonged/obstructed labor or failure to progress, breech or transverse presentation, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, non-reassuring fetal status/cord prolapse/meconium, previous CD, elective CD, and no clear indication or other) were relatively stable over time, as shown in Table 2. No CD were reportedly performed for severe antenatal hemorrhage or ruptured uterus. The most common indications for CD overall were prolonged/obstructed labor and failure to progress (47.5%), baby in transverse or breech presentation (14.5%), and history of a prior CD (19.8%).

Table 2.

Reported Reasons for Indication for Cesarean Delivery in the SW Trifinio Population, 2015 – 2017.

| Reported Indication for Cesarean Delivery | 2015 (n = 15)a |

2016 (n = 105) |

2017 (n = 58) |

All (n = 178) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prolonged/Obstructed Labor or Failure to Progress | 6 (40.0%) | 50 (48.1%) | 28 (48.3%) | 84 (47.5%) |

| Baby in breech or transverse position | 6 (40.0%) | 10 (9.6%) | 10 (17.2%) | 26 (14.7%) |

| Pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (3.4%) | 4 (2.3%) |

| Non-reassuring fetal status/cord prolapse/meconium | 2 (13.3%) | 13 (12.5%) | 1 (1.7%) | 16 (9.0%) |

| Previous CD | 0 (0%) | 21 (20.2%) | 14 (24.1%) | 35 (19.8%) |

| Elective CD | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.1%) |

| No clear indication/Other | 0 (0%) | 12 (11.5%) | 3 (5.2%) | 15 (8.5%) |

Number (percent)

n = number of women. A woman may have had multiple indications.

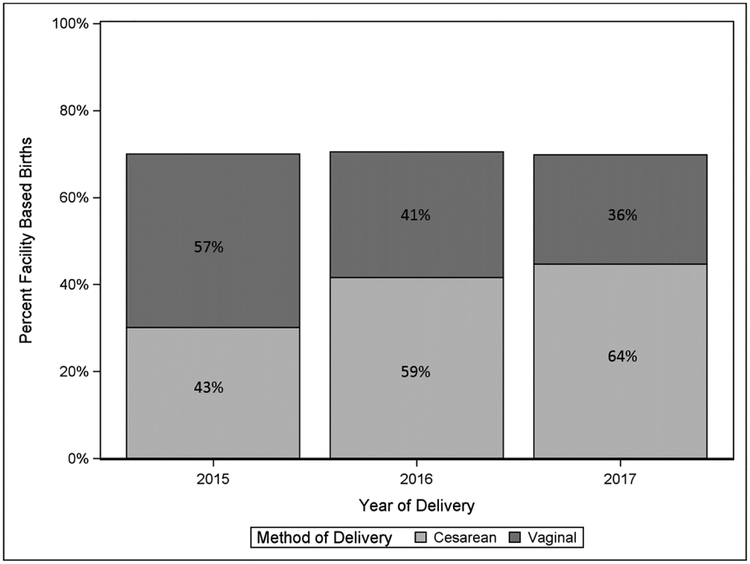

To evaluate if the increasing rate of CD was being driven by an increase in institutional deliveries we compared the trend in location of delivery over the same period. Trends in facility births (Figure 3) of women from the community did not increase over time, while the rates of CD did rise. We then observed rates of CD in the previously described NTSV population to test the hypothesis that this group could account for the increasing rate of CD in the SW Trifinio communities. We found that women who fulfilled the NTSV definition accounted for 20% of all CD in the study population in 2015 (able to categorize 15 of 15 women undergoing CD), 38% of all CD in 2016 (104 of 105 women undergoing CD were able to be categorized), and 38% of all CD in 2017 (able to categorize 55 of 58 women who underwent CD).

Figure 3.

Facility-Based Deliveries and the Proportion of all Deliveries that were Delivered by Cesarean Section, 2015 – 2017.

We also compared NTSV women who delivered vaginally to women who underwent CD to determine between group differences. We found the patients differed significantly only by gestational age at delivery, but not by maternal age, marital status, or educational level. We were not powered to test associations between method of delivery and postpartum mortality, including stillbirth, neonatal death, or maternal death. NTSV women who underwent VD delivered on average at 39 weeks and 5 days, while NTSV women who underwent CD delivered on average at 40 weeks and 3 days (39.7 ±1.4 days versus 40.4 ± 1.7 days, P = 0.02). Of note, the indications for NTSV CD did not differ from the entire cohort (data not shown).

We also explored antepartum potential factors associated with method of delivery to determine if we could predict or explain the indications for CD due to comorbid maternal or fetal conditions. These outcomes are displayed in Table 3, which demonstrate that only prolonged/obstructed labor and transverse/breech presentation were associated with method of delivery. We then explored if any antepartum condition was associated with CD when controlling for age, parity, and year of delivery (Table 4). We found that women with a labor complicated by prolonged/obstructed labor had a 3.6 times higher risk of CD (CI 2.9 – 4.5, p < 0.001), and women with a baby in transverse or breech presentation had a 2.6 times higher risk of CD (CI 2.2 – 3.2, p < 0.001). If a woman experiences any one of the antepartum conditions listed in Table 3, her risk of CD is 5.6 times higher (CI 4.3 – 7.4, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Antepartum Risk Factors and Their Association with Method of Delivery in the SW Trifnio Population, 2015 – 2017.

| Antepartum Risk Factors | Vaginal Delivery (n = 252)a |

Cesarean Delivery (n=178) |

P-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prolonged/Obstructed Labor | 6 (2.4%) | 99 (55.6%) | <0.001 |

| Severe antenatal hemorrhage | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.4 |

| Hypertension in Pregnancy | 1 (0.4%) | 4 (2.2%) | 0.17 |

| Baby in transverse/breech presentation | 0 (0%) | 29 (16.3%) | <0.001 |

| Premature Labor | 3 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.2 |

| Infection | 1 (0%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.6 |

| Prior Cesarean Section | 20 (7.9%) | 66 (37.1%) | <0.001 |

Number (percent)

n= number of women. A woman may have had multiple factors.

Fisher’s Exact test.

Table 4.

Antepartum Risk Factors Associated with Cesarean Section (Controlled for Age, Parity, and Year of Delivery) in the SW Trifinio Population, 2015 – 2017

| Condition | RRa | Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prolonged/Obstructed Labor | 3.6 | 2.9 – 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Transverse/Breech Presentation | 2.6 | 2.2 – 3.2 | <0.001 |

| Any Antepartum Condition | 5.6 | 4.3 – 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Prior Cesarean Section | 4.8 | 3.4 – 6.9 | <0.001 |

Bivariate poisson regression model with a robust error variance adjusting for age, parity and year of delivery was used to estimate the relative risks (RR), confidence intervals and p-values

Discussion:

The CD rate is increasing for women in rural southwest Guatemala and does not seem to be related to the proportion of facility-based obstetrical care. Younger, nulliparous women who experience prolonged or obstructed labor and have fetal malpresentation are most likely to experience CD. The leading indications for CD are labor dysfunction, malpresentation, and prior CD. While the NTSV CD rate also appears to be increasing, the data was not complete enough to classify all women in the cohort and thus we did not test the increasing trend for significance.

Our finding that younger, nulliparous women in our population are more likely to undergo CD is similar to the results of other studies previously reported in the global literature (Belizan 1999, Ronsmans 2006) Our retrospective analysis was not able to capture possible explanations for observed changes in mode of delivery, but one hypothesis is that the time period for allowing a woman to enter active labor is foreshortened, in contrast to current evidence-based management (Zhang 2002). Current recommendations for labor management and the definition of labor dysfunction suggest that labor becomes active at 6cm (as opposed to the traditional 4cm) (Zhang 2002, Friedman 1955). For providers using the partograph, women may be advised to undergo CD or called failure to progress before they have had adequate time to enter the active phase. Additionally, supportive measures that increase VD such as effective pain control, labor support, and regional anesthesia, interventions that have been shown to decrease the CD rate are not routinely or consistently available (WHO 2018).

WHO has published a brief specifically addressing the rising rate of CD in Latin America based on the results of a maternal and perinatal health survey (WHO 2009). Some key findings were that the overall CD rate in the survey was 35.4%, CD rates were higher in private hospitals (which the authors attributed to elective cesarean delivery), and the highest proportion of CD were performed for women with a history of CD with a singleton fetus in cephalic position at term, and women without a history of CD who had labor induced or had a pre-labor (elective) CD.17 Understanding how some of these factors influence mode of delivery in this population would be a good area for future research. Some women who are experiencing a rising CD rate might be targeted for specific interventions. For example, WHO is currently working on guidelines to prevent primary cesarean sections in LMIC. Similar guidelines have previously been published by other organizations such as the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG 2016). These guidelines include measures such as offering external cephalic version to women with a breech fetus and adhering to a definition of arrest of labor that gives women more time in the first and second stages of labor. All women who undergo CD can be separated into ten mutually exclusive subgroups using the Robson Criteria (WHO 2017). The WHO recommends tracking these specific subgroups as a method to understand why the CD rate is increasing in any given population (Vogel 2015). The NTSV population is one of these subgroups.

In exploring the NTSV population, we did find a significant difference in gestational age at delivery between the women whose labor ended in vaginal delivery compared to women who experienced CD, with a difference of almost one week. In a large clinical trial performed in the United States to evaluate the effect of induction of labor at 39 weeks on clinical outcomes, the preliminary data concluded that 39-week induction statistically significantly reduces CD without increasing the frequency of a composite of adverse perinatal outcomes (Grobman 2018). Similarly, our cohort was also less likely to be delivered by CD if they were less than 40 weeks gestational age.

Another area of interest to explore in future research is the delivery of care in the hospital most proximate to the Madres Sanas site. This regional hospital, located in Coatepeque, has an obstetrics and gynecology residency training program. The fact that trainees are involved in patient care, and that currently there are no regional, national, or international guidelines on preventing primary CD, their need for improving their CD operative skills may be a contributing factor to the rising CD rate and warrants further study. Exploring whether or not current management practices include external cephalic version, offering vaginal breech delivery, and how delivery related to pre-eclampsia is managed would be of interest. For example, if all women with pre-eclampsia are moved to CD without consideration of induction of labor, this could be a target area for reduction in CD rates.

Additionally, it would be remiss not to discuss the impact of increased CD rates on future pregnancies and fertility, globally. The primary risk of trial of labor after a history of CD is uterine rupture (ACOG 2017). Taking into consideration a woman’s various individual risk factors for adverse outcomes following a vaginal birth after cesarean section, such as the indication for the prior delivery or medical complications of pregnancy, a trial of labor is generally considered a safe alternative to repeat cesarean delivery.22 Repeat cesarean delivery is associated with higher rates of abnormal placentation, resulting in placenta increta, percreta, and accreta, which are in turn associated with cesarean hysterectomy and maternal death.22 The impact of CD on maternal health should be considered not only in the context of the index labor and delivery, but also in terms of the impact it could have on maternal morbidity and mortality in subsequent pregnancies.

Strengths of our analysis include consistent methods of data collection, that the program is well-received by the community members, and that there is a good retention rate (over 90% of women are seen for their postpartum visit). Our analysis is limited by the fact that it is a secondary analysis of a cohort of women enrolled and followed in a registry designed to monitor and improve quality. Thus, its retrospective nature makes it difficult to elucidate risk factors. Additionally, the data is collected by patient self-report, and women may not have enough health literacy to understand and report certain morbidities and medical conditions.

Despite good maternal and neonatal survival, the Southwest Trifinio region of Guatemala has a high rate of CD, and CD among nulliparous, term women with singleton fetuses in vertex presentation. Additionally, CD rates appear to be increasing. Risk factors for CD include malpresentation, prolonged/obstructed labor, and prior CD. These results suggest that more research into understanding the increasing CD rate, programmatic interventions to improve labor management in hospitals, and a focus on non-hospital delivery locations for low-risk populations (such as birth centers) may be warranted.

Significance: CD rates are increasing globally and in Latin America. Our study adds to the evidence showing that method of delivery is rapidly changing even in the most impoverished and geographically isolated locations. Evaluating the determinants of this transformation are important for health care systems.

Acknowledgements:

We wish to sincerely thank each nurse working in the Madres Sanas program who collected the data and provided such high quality maternal healthcare to the community (Claudia Rivera, Yoselin Velasquez, Karen Altun, Silivia Aragon, Alisse Hernandez, Cristal Gonzalez, Alba Gabriel, Dulce Gramajo), and the community leaders and women who participated in the program.

Funding Source: funding for the Madres Sanas Program was provided by a donation from Agroamerica and the Jose Fernando Bolanos Foundation and by the NICHD WRHR K12 Program (5K12HD001271–18)

Footnotes

Ethical Statement: This study was deemed non-human subjects’ quality improvement by Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB). This secondary analysis of a de-identified subset of the database was approved by COMIRB, #17–1941.

References:

- Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A et al. Cesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet 2006; 367: 1819–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gulmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in cesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990 – 2014. Plos One 2016, 2: e0148343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales GF, Tapia VL, Fort AL, Betran AP. Pregnancy outcomes associated with cesarean deliveries in Peruvian public health facilities. International Journal of Women’s Health 2013, 5: 637–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MS, Pasha O, Saleem S, Ali S, Chomba E, Carlo WA. A prospective study of maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes in the setting of cesarean section in low- and middle-income countries. Acta Obst et Gynec Scand 96 (2017) 410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira GO, Fernandes LG, de Oliveira NF, Silva LR, de Oliveira Vieira T. Factors associated with cesarean deliveryin public and private hospitals in a city of northeastern Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2015, 15: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K, de Lima Amaral EF, Mourao ANM. The impact of payment source and hospital type on rising cesarean section rates in Brazil, 1998 to 2008. Birth 2014, 41(2): 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons L, Belizan JM, Lauer JA, Betran AP, Merialdo M, Althabe F. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary cesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- State of the World’s Children. Accessed 9.13.18 (https://www.unicef.org/sowc2013/files/SWCR2013_ENG_Lo_res_24_Apr_2013.pdf)

- Encuesta Nactional de Salud Materno Infantil 2014 – 2015. Accessed 9.13.18 (https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR318/FR318.pdf)

- Beogo I, Rojas BM, Gagnon MP. Determinants and materno-fetal outcomes related to cesarean section delivery in public and private hospitals in low- and middle-income countries: as systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Systematic Review 2017, 6: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asturias EJ, Heinrichs G, Domek G, Brett J, Shick E, Cunningham M et al. The Center for Human Development in Guatemala: an innovative model for global health population. Advances in Pediatrics 2016, 63: 357–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belizan JM, Althabe F, Barros FC, Alexander S. Rates and implications of cesarean sections in Latin America: ecological study, 1999. BMJ 319: 1397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronsmans Carine, Holtz Sara, Stanton Cynthia. Socioeconomic differentials in caesarean rates in developing countries: a retrospective analysis, 2006. The Lancet 368 (9546): 1516–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Troendle JF, Yancey MK. Reassessing the labor curve in nulliparous women. AJOG 2002, 187 (4): 824–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol 1955, 6 (6): 567–589.13272981 [Google Scholar]

- WHO Recommendations: Intrpartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Accessed 6.26.18 (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260178/9789241550215-eng.pdf?sequence=1) [PubMed]

- Rising Cesarean Deliveries in Latin America: how best to monitor rates and risks. World Health Organization, 2009. Accessed 5.2.18 (http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/rhr_09_05/en/) [Google Scholar]

- Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery. Accessed 12.15.17 https://www.acog.org/-/media/Obstetric-Care-Consensus-Series/oc001.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20171215T2011579906

- Robson Classification: Implementation Manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Joshua P et al. Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys.The Lancet Global Health, Volume 3, Issue 5, e260–e270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobman W, NICHD MFMU. A randomized trial of elective induction of labor at 39 weeks compared with expectant management of low-risk nulliparous women. AJOG 2018, S601. [Google Scholar]

- Vaginal Birth After Cesarean. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017. Accessed 9.13.18 (https://www.acog.org/-/media/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-Practice-Bulletins----Obstetrics/pb184.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20180913T1935497773)