Abstract

Background:

the current evidences attest UVA1 phototherapy as effective in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis (AD). Furthermore in this indication, “medium dose” is as effective as “high dose” regimen in this indication. To date, a randomized comparison study evaluating the effectiveness as well as safety of different UVA1 protocols in different skin types in the treatment of adult patients with severe AD is still lacking.

Objective:

The aim of the present study was to compare the safety and the efficacy of medium and high dose UVA1 either in fair or in dark skin types. which are more common among Italian population.

Methods:

Twenty-seven adult patients with severe AD were consecutively included in a randomized, controlled, open, two arms trial prospective, open, randomized, 2 arms study. Severity of AD was determined by means of SCORAD index and clinical improvement was also monitored. A total of 13/27 patients were treated with High Dose (130 J/cm2) UVA1 protocol while 14/27 patients received Medium Dose (60 J/cm2) UVA1 protocol. Phototherapy was performed 5 times weekly up to 3 weeks. Before and after UVA1 treatment each patient was evaluated for skin pigmentation through Melanin Index (MI) quantitative evaluation.

Results:

Skin status improved in all patients resulting in a reduction of SCORAD index in all groups. Our results demonstrated that among patients with darker skin types and higher MI, High dose UVA1 was significantly more effective than Medium Dose (p < 0.0001) while within the groups with skin type II, no significant differences between high and medium dose protocols were observed.

Conclusion:

Our study, further confirms previous observations that UVA1 phototherapy should be considered among the first approaches in the treatment of patients with severe generalized atopic dermatitis and also demonstrates that in darker skin types, high dose UVA1 phototherapy is more effective than medium dose in the treatment of adult patients with severe AD.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic Dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin disease characterized by severe pruritus, typical eczematous morphology and a chronic relapsing course that usually first appears in childhood and frequently persists into adult life.1

The prevalence of AD has increased constantly in recent decades and in developed countries, approximately 10-15% of children under 5 years of age are affected at some stage.2-3 To the best of our knowledge heterogenous and controversial data are currently available toward the prevalence of AD among adults suggesting that the variability could be dependent on different geographic areas and methodology.3

Histologically, AD is characterized by an increased number of T lymphocytes, predominantly CD4+ T-helper cells, related to the expression of a specific cytokine pattern.4

The aetiology of the disease is still unknown but there are data supporting the crucial role of the genetic background as well as the influence of environmental triggering factors.4 Although AD has been characterized as a T-cell mediated immune response directed toward several inhalant allergens and it has been suggested that a shift of the T cell balance from Th1 into Th2 cells is an important pathogenetic mechanism, recent studies revealed that patients initially exhibit Th2 like immune responses early in the acute stage and switch to a Th1 like profile as chronic lesions emerge.5-6

Severe AD does not respond well to conventional therapies consisting in most cases of topical or systemic corticosteroids. New Treatment modalities including topical calcineurin inhibitors, interferon gamma or cyclosporine are often accompanied by several side effects, which make them a poor choice for the long term treatment of AD.1, 7-9 Although literature still do not offer enough clinical evidence supporting the effectiveness of the Janus Kinase Inhibitors (Jakinibs) in adult patients affected by recalcitrant acute exacerbations of AD, the success of these molecules in the treatment of several autoinflammatory dermatological diseases suggests the successful possible use of JAK inhibitors in adults patients with severe forms of AD.10

Biologic therapies have shown encouraging results in those patients with severe forms of AD acting through their target effects on altered inflammatory responses responsible for acute severe relapses. Among these drugs category, the fully humanized monocolonal antibody targeting IL-4 and IL-13 Dupilumab, has demonstrated to be effective in treating symptoms of adult patients with severe AD in a dose dependent manner.11-12

Several reports have suggested that Phototherapy is an effective treatment modality in patients with acute, severe exacerbation of AD. Many studies described beneficial effects of either UVB or UVA administration or combined UVA/UVB radiation in AD.13 The use of PUVA is nowadays limited especially in children, because of the frequent side effects and long-term carcinogenetic risk.14

UVA1 (340-400 nm) phototherapy has been introduced in 1992 by Krutmann et al. as an effective novel treatment modality for patients with severe, generalized AD as well as for other inflammatory skin diseases characterized by epithelial and dermal infiltrates rich in T lymphocytes.15 In fact, UVA radiation It acts on cytokine production by suppression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-12) that activates antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). acts as a potent inducer of the immunosuppressive cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10) in human keratinocytes and upregulates Fas-Ligand gene expression in skin infiltrating T cells apoptosis. UVA1 induced apoptosis differs from apoptosis observed in UVB irradiated cells since it is mediated through a pathway not requiring protein synthesis (early apoptosis). The early apoptosis, highly specific for UVA1 radiation and responsible for the therapeutic effectiveness of UVA1, is mediated through generation of singlet oxygen.16-17

The optimal treatment regimen has not yet been determined. Findings of a randomized controlled trial have shown that high dose UVA1 is as effective as moderately potent topical steroids for acute, severe atopic eczema.18

In 1995 Kowalzick et al. stated that medium dose is also effective for severe atopic dermatitis and more effective than low dose treatment.19

A controlled study performed by Tzaneva et al, compared high daily doses (five times weekly for 3 weeks) with medium doses. This study was a involved within–subject comparisons of the two regimens and The results demonstrated that medium dose UVA1 was as effective as high dose UVA1 treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis in 9/10 patients.20

Since the widespread use of the UVA1 phototherapy has been introduced, no serious negative side effect in humans has been published except for a single case report of melanoma in a patient with mastocytosis that received a long course of UVA1 phototherapy21 and a report by Calzavara-Pinton et al. where the Authors demonstrated that, repeated suberythemogenic UVA1 doses, had favoured the development of Merkel Cell Carcinoma in two immunosuppressed patients.22 In vitro cell culture and in vivo animal studies demonstrated had widely shown that UVA irradiation accelerates photoaging and may thus contribute to the risk of skin carcinogenesis and melanoma induction.23-26

Based on these findings, in order to avoid potentially harmful side effects induced by UVA1 therapy, the aim of our study was to determine which UVA1 protocol is safer and more effective in treating severe generalized AD also considering the different therapeutic reaction in a population with darker skin types. Our 2 comparative study groups consisted of patients with darker skin types who had received either medium (60 J/cm2) or high (130 J/cm2) dose UVA1 regimens and of patients with lower skin types who had received either medium or high dose UVA1 treatments.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This was a randomized, controlled, investigator blinded open trial study conducted at the Phototherapy Unit of S. Gallicano Institute from October 2008 to February 2010.

Twenty-seven patients with severe AD involving the scalp, face, neck, trunk and extremities (14 females, 13 males; range 19-47, mean age 34.7 years) were enrolled in this study after informed consent was obtained. AD was defined according to criteria proposed by Hanifin and Rajka and severity of the disease was evaluated clinically using SCORAD index.27 The possible score ranges between 0 (lowest possible score) and 103 (highest possible score) and it is clinically interpreted as follows: < 25: Mild AD; 25-60: moderate AD; > 50: Severe AD.

All patients were white and had Fitzpatrick skin type IV (n = 8), III (n = 6), II (n = 13).

Patients with darker skin type (III-IV) as well as subjects with skin type II were randomly assigned to one of the 2 different treatment regimens (High dose or medium dose UVA1 therapy). Among the group receiving a high dose (130 J/cm2) protocol, 8 patients were skin type III-IV and 5 patients were skin type 2 while in the group receiving medium dose (60 J/cm2) protocol 8 patients were skin type II and 6 patients were skin type III-IV.

The clinical severity of disease was measured by means of the SCORAD index before and after UVA1 therapy.28 Briefly, the SCORAD system developed by the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis, assesses the extent of the disease and it is composed of a maximum score of 20 points for body surface extension of lesions, a maximum score of 62 points for representative presence of erythema, infiltration, exudation, excoriation and lichenification including skin dryness, and a maximum score of 20 points for presence of pruritus and sleep loss judged by the patient.26

Data regarding patients’ characteristics and SCORAD at baseline are listed in Table 1.

Table 1:

patients’ characteristics (mean SCORAD T0: 54.1;); MI: Melanin Index; W0: baseline; W3: end of the study, week 3

| Pt | Sex | Age | Skin type |

UVA1 | SCORAD W0 (relative) |

SCORAD (relative) W3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 19 | IV | High | 47 | 26 |

| 2 | M | 32 | IV | High | 45 | 24 |

| 3 | M | 41 | IV | High | 50 | 31 |

| 4 | F | 36 | III | High | 46 | 25 |

| 5 | F | 38 | IV | High | 56 | 38 |

| 6 | M | 27 | III | High | 48 | 27 |

| 7 | F | 45 | III | High | 60 | 33 |

| 8 | F | 48 | IV | High | 58 | 38 |

| 9 | M | 39 | II | High | 53 | 34 |

| 10 | F | 34 | II | High | 60 | 38 |

| 11 | M | 27 | II | High | 58 | 40 |

| 12 | F | 31 | II | High | 53 | 33 |

| 13 | F | 25 | II | High | 60 | 39 |

| 14 | F | 33 | IV | Medium | 65 | 58 |

| 15 | M | 37 | III | Medium | 60 | 51 |

| 16 | M | 41 | IV | Medium | 65 | 59 |

| 17 | F | 22 | III | Medium | 50 | 42 |

| 18 | F | 47 | III | Medium | 45 | 40 |

| 19 | M | 20 | IV | Medium | 64 | 57 |

| 20 | M | 28 | II | Medium | 49 | 32 |

| 21 | F | 36 | II | Medium | 51 | 33 |

| 22 | M | 43 | II | Medium | 45 | 27 |

| 23 | M | 39 | II | Medium | 48 | 32 |

| 24 | F | 41 | II | Medium | 58 | 38 |

| 25 | F | 28 | II | Medium | 56 | 37 |

| 26 | F | 35 | II | Medium | 51 | 34 |

| 27 | M | 46 | II | Medium | 60 | 39 |

Only patients with severe AD resulting in an initial score of greater than 45 points were included (mean SCORAD of study population: 54.1). The power of the study was evaluated assuming that at least 13 patients for each group (26 in total) would have been needed in order to observe a statistically significant between group difference of at least 20% in the reduction of the SCORAD from baseline (SD in each group = 15%, alpha = 0.05, beta= 0.10, two tailed test). Randomization has been performed using a computer generated sequence.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: age younger than 18 years, bacterial superinfection, pregnancy or lactation, systemic therapy with antibiotics, immunomodulating drugs, antihistamines within the last 6 weeks, topical corticosteroid therapy within the last 2 weeks, phototherapy within the last 12 weeks, autoimmune disease and a positive history for photosensitive disorders and skin tumours.

All patients were assessed by the same observer who was not informed about the treatment protocol of the patient. Photographs of each patient were taken both before and after phototherapy.

Technical equipment

The UVA1 treatment was performed with a Sellamed 24000 lay down unit (Systems Dr Sellmeier, Gevelsberg-Vogelsang, Germany) emitting almost exclusively UVA1 light. Irradiance was determined using a Variocontrol dosimeter (Waldmann, Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany) and the total irradiance at skin level was 78 mW/cm2.

Phototherapeutic protocol

In the groups treated with UVA1 high dose protocol, phototherapy was administered 5 times weekly for 3 weeks resulting in a total of 15 treatment sessions. Each session consisted of an exposure of 130 J/cm2 UVA1, resulting in a mean cumulative dose of 1950 J/cm2. During therapy, patients wore eye goggles as protection against UVA radiation.

In the groups treated with UVA1 medium dose protocol, phototherapy was given 5 times weekly for 3 weeks, resulting in a total of 15 treatments. Each treatment session consisted of an exposure of 60 J/cm2 UVA1 resulting in a mean cumulative dose of 750 J/cm2.

For both regimens, we started treatment with slowly increasing doses until reaching the maximum dosage (high dose progression: 60J-90J-130J; medium dose progression: 30J-60J) and a total of 15 sessions has been administered.

Pigmentation measurements

Before and after UVA1 treatment each patient was evaluated for skin pigmentation with a non-invasive diagnostic technique.

A skin reflectance measuring instrument, Mexameter MX16 (Courage & Khazaka Electronics, Cologne, Germany) was used to measure the Melanin Index under illumination with the combination of 568, 660 and 880 nm wavelengths. The MI is computed from the absorbed and remitted light at 660 and 880 nm, respectively.

Six body sites were assessed on each subject. The reflectance readings were taken on the inner aspect of upper part of the arm, the mid-ventral forearm, the mid-dorsal forearm, the forehead, the anterior and posterior upper parts of the trunk.

Statistical analysis

According to the Kolmogorov Smirnov test, data were not normally distributed and as such are represented as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Differences in the relative reduction of clinical score from baseline between patients performing high dose vs. medium dose treatment were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test.

Pearson’s correlation between the relative reduction of clinical score and mean baseline MI was also investigated by using linear regression analysis. A p value of less than .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Twenty-seven patients fulfilled entry criteria and either those with darker skin type (III-IV) or subjects with light skin type (II) were randomly selected to receive one of the two treatment regimens: high dose or medium dose. All the 27 patients completed the 3 weeks of therapy in a compliant manner and all were included in the statistical analysis for efficacy. Both groups received 15 total treatments. In these 15 treatments are included the lower and the intermediate dosage in the high dose group.

Patients’ relative SCORAD and MI parameters were evaluated at baseline (W0) and after 3 weeks UVA1 treatment (W3)

In darker phototypes, high dose UVA1 resulted in a median relative reduction of the SCORAD index by 44.22% (Figs 1-2) after 3 weeks (W3) of treatment while medium dose determined a median relative reduction of SCORAD index by 11.02% (Figs 3-4), assuming that high dose UVA1 was significantly more effective than medium dose UVA 1 (p =0.002) (Table 2) .

Figure 1:

patient with dark skin type treated with high dose UVA1 at W0

Figure 2:

patient with dark skin type treated with high dose UVA1 at W3

Figure 3:

patient with dark skin type treated with medium dose UVA1 at W0

Figure 4:

patient with dark skin type treated with medium dose UVA1 at W3

Table 2.

Comparison of relative W0 and W3 SCORAD index of AD lesions in patients with dark skin type

| Evaluation | High dose UVA1 (n= 8) | Medium dose UVA 1 (n=6) | Comparison of Treatment Groups by Delta Values |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Delta (%) | Median (IQR) | Delta (%) | ||||

| Baseline | End of Study | Baseline | End of Study | ||||

| SCORAD score | 49.00 (46.75-56.50) | 29.00 (25.75-30.25) | −21 (−44.22%)* | 62.00 (52.50-64.75) | 54 (44.25-57.75) | −7 (−11.02%)* | P=0.002 |

p<0.001

In fair phototypes groups, high dose UVA1 regimen determined a median relative reduction of the SCORAD index by 35.9 % versus 34.59% of the medium dose UVA1 protocol. No difference in therapeutic efficacy was found between the two dosages and statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the two regimens (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of relative W0 and W3 SCORAD index of AD lesions in patients with fair skin type

| Evaluation | High dose UVA1 (n= 5) | Medium dose UVA 1 (n=8) | Comparison of Treatment Groups by Delta Values |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Delta (%) | Median (IQR) | Delta (%) | ||||

| Baseline | End of Study | Baseline | End of Study | ||||

| SCORAD score | 58.0 (53.0-60.0) | 38.0 (34.0-39.0) | −20.00 (−35.9%)* | 51.0 (48.75-56.5) | 33.5 (32-37.25) | −18.00 (−34.59%)* | P=0.10 |

p<0.001

Despite this positive result, no patient experienced complete clearing of symptoms during treatment. The median reduction of the relative SCORAD value was mainly because of the reduction of symptoms such as itching, sleep loss, erythema, infiltration, exudation and excoriation as well as surface extension.

As already reported by other Authors, in patients with dark skin complexion who performed high dose protocol and in patients with skin type II who performed either medium or high dose protocol, we observed a rapid therapeutic response already within the first week of treatment.

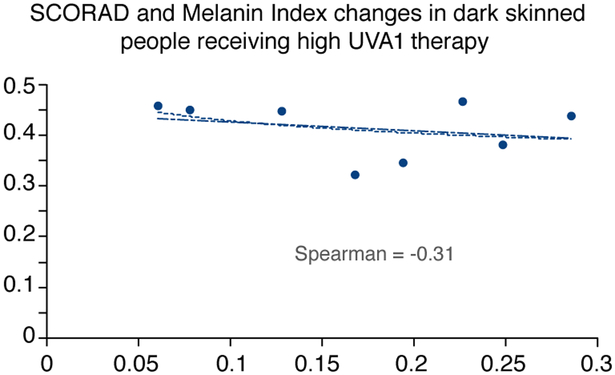

Interestingly, in subjects with skin type III and IV, we observed that patients with a higher MI experienced a better efficacy with the high dose UVA1 protocol (Figs 5-6).

Figure 5:

SCORAD and MI changes in dark skinned people receiving high dose UVA1 phototherapy

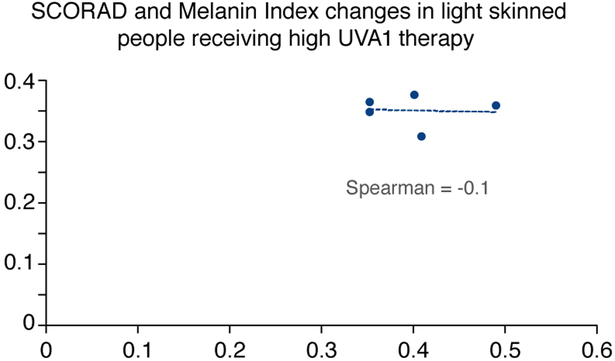

Figure 6:

SCORAD and MI changes in light skinned people receiving high dose UVA1 phototherapy

Treatment was well tolerated and no erythema and other side effects were recorded except for skin dryness associated with mild pruritus immediately after UVA1 therapy, treated only with emollients.

DISCUSSION

UVA1 phototherapy in monotherapy has emerged as a highly effective and well-tolerated treatment in a variety of inflammatory disorders including atopic dermatitis.29-31

UVA1 in monotherapy was initially administered to patients with AD according to a high dose regimen but during the last years, numerous trials confirmed that not only high dose but also medium dose UVA1 induces significant improvement in adult patients with acute exacerbations of AD and that high/medium dosage are both more effective than UVA/UVB or low dose UVA1 treatment.32

Concerns towards long term side effects associated with massive UVA1 dosages, led many photodermatologists to use a medium dose protocol. Although in 2008 Jacobe et al. in a retrospective study conducted on 101 patients stated that even if skin pigmentation does not significantly influence effectiveness of UVA1 and this source could be considered a therapeutic option in patients with darker skin type, controlled trials on dose-response relationship in a population with a predominance of darker skin types have not yet been performed.33

In our study, the effectiveness of UVA1 phototherapy in monotherapy has been investigated and also the efficacy of high and medium dose UVA1 protocols has been compared in a series of adult patients with severe acute AD. Patients included into study groups were similar for demographic characteristics, baseline extent of the disease and severity of subjective symptoms. Unlike the majority of the studies already published on UVA1 where a smaller number of dark phototypes were considered, we enrolled patients either with fair or dark skin types and we also monitored the variation of MI during UVA1 therapy at different dosage and we finally tried to correlate changes in the MI with the SCORAD index.

Exposure of the skin to UV radiation results in an increased melanin production and consequently increased pigmentation (tanning), a process that can be considered as a natural defence mechanism of the organism.34

Melanin is generally considered as the major defence of the skin against the harmful effects of solar light. This photoprotective role of melanin is related to its ability to absorb radiation in the ultraviolet, visible and infrared spectra. The ratio of eumelanin and pheomelanin plays an important role in the degree of the physiological skin protection: the darker the skin type, the more eumelanin action as a free radicals scavenger the skin contains. In lighter skin types the ratio is lower and the role of pheomelanin is more prominent and contributes to skin damage by producing free radicals such as superoxide.35-36

One mechanism that possibly accounts for the skin type related differences is the skin antioxidant status. An increased body of evidences suggest that antioxidants provide photoprotection. To the same regard Picardo et al. showed that there are significant differences in antioxidant status in normal skin between people with high (III-IV) and low (I-II) skin type: the higher the skin type is, the higher the amount of catalase. Possibly, the same differences in antioxidant status between the different skin types exist in AD patients which could account for the differences observed in our study.37

Skin pigmentation is induced both by UVB and UVA rays. UVA induced tanning involves at least three distinct photobiological reactions: the immediate transient darkening (immediate pigment darkening, IPD), the lasting immediate pigmentation (persistent pigment darkening, PPD) and the delayed pigmentation (neo-melanization) which occurs after UVA induced erythema or after repeated exposure to sub-erythemogenic UVA doses. UVB induced tanning is a delayed pigmentation, generally subsequent to sunburn and usually disappears with epidermal turnover within a month.36-38

UVA has been divided into UVA1 (340-400 nm) and UVA2 (320-240 nm) since UVA2 induces similar effects to that of UVB.36 The action spectrum for the immediate pigmentation phenomenon (both IPD and PPD) ranges from UVA2 to the longer wavelengths of UVA1 including the first part of visible wavelengths, with a more pronounced peak in the UVA2 and another peak in longer UVA1. PPD is a stable response linearly dependent on the amount of UVA radiation that penetrates trough the epidermis whereas it is independent of the fluence rate of the UVA source. UVA induced tanning, which results from repeated cumulated exposures, is more prominent and lasting. This difference is probably because of the location of UVA induced pigments at basal level.37 IPD, as compared with delayed pigmentation is not considered to have a relevant photoprotective effect, probably because it represents photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin while delayed pigmentation depends on “de novo” synthesis of melanin with translocation of newly formed melanosomes in the overlying keratinocytes.37-41

In our opinion, this might be correct but it is referred only to the photoprotective effect against UVB that is unable to penetrate deeper through the dermis. The action spectrum for the immediate pigmentation phenomenon (IPD and PPD) ranges from UVA2 to UVA1 wavelengths including the first part of visible light.38 Although IPD is generated from photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin, in the case of longer UVA (340 nm-400 nm) irradiation that penetrate deeper through the skin reaching the dermis, it could represent a manifestation of a photoprotective pathway. Furthermore, considering the long duration of treatment sessions particularly in the case of high dose UVA1 phototherapy, the immediate pigmentation phenomenon can attain the highest intensity and become almost stable.39-43 This might explain the results observed in our study that in patients with darker skin types, in whom the immediate pigmentation is more prominent, only part of the UVA1 radiation may have therapeutic effects thus requiring higher doses than those needed in lower skin types.

In the present study although none of the patients obtained a complete clearing of cutaneous eczematous lesions, a linear relationship between patients’ MI and efficacy of UVA1 phototherapy (Figs 5-6) has been highlighted. In dark skin types a high MI is observed before treatment and both medium and high dose UVA1 induce a relevant increase in MI at the end of treatment, but high dose has major chances to counteract the increase in pigmentation than medium dose, thus penetrating in sufficient amount and leading to satisfying therapeutic results. In subjects with lower skin type instead, both high dose and medium dose UVA1 induce the same scarce increase in MI and in these patients a higher dosage of irradiation does not lead to a better therapeutic response. This may be explained by the different patterns of pigmentation response in different skin types: while in lower skin types the IPD/PPD response is less important, in higher skin types even lower dosages of UVA1 may induce a rapid increase mainly in the IPD/PPD but also in delayed pigmentation.43-44 In darker skin types consequently, it is crucial to consider the possibility that UVA1 radiation presents a decreased ability capacity of penetration through the skin.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that in fair skin types medium dose UVA1 is nearly as effective as high dose treatment in alleviating severe atopic dermatitis while in dark skin types, high dose UVA1 protocol is significantly more effective than medium dose. These preliminary considerations aimed to avoid in patients with darker skin types the use of longer periods of medium dose UVA1 courses with an increased number of treatments and UV cumulative dose

It would be interesting in the next future a study evaluating differences of skin type III vs. type IV patients following UVA1 treatment, in order to clarify whether type III patients really belong to the higher pigmentation group or whether their data were overruled by the greater effect in the type IV patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Funding Sources: RRZC is supported by the 5 T32 AR 7569-22 National Institute of Health T32 grant, RRZC and GD is supported by the P50 AR 070590 01A1 National Institute Of Arthritis And Musculoskeletal And Skin Diseases.

Contributor Information

Alessia Pacifico, Clinical Dermatology Department, S. Gallicano Dermatological Institute, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

Paolo Iacovelli, Clinical Dermatology Department, S. Gallicano Dermatological Institute, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

Carmela Ferraro, Clinical Dermatology Department, S. Gallicano Dermatological Institute, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

Giovanni Leone, Clinical Dermatology Department, S. Gallicano Dermatological Institute, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

Aldo Morrone, Clinical Dermatology Department, S. Gallicano Dermatological Institute, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1).Abramovits W Atopic Dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53: S86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Karsen FS, Hanifin JM. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Clin North Am 2002; 22: 1–24 [Google Scholar]

- 3).Kim JP, Chao LX, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 681–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Larse FS, Holm NV, Henningsen K. Atopic dermatitis. A genetic-epidemiologic study in a population based twin sample. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 15: 487–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Asadullah K, Sterry W, Trefzer U. Cytokines: interleukin and interferon therapy in dermatology. Clin Exp Dermatol 2002; 27: 578–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Leung DYM. Atopic dermatitis: new insights and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 105: 860–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Kooper KD. Atopic dermatitis: recent trends in pathogenesis and therapy. J Invest Dermatol 1994; 102: 128–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Van Joost T, Kozel MM, Tank B, Troost R, Prens EP. Cyclosporine in atopic dermatitis: modulation in the expression of immunologic markers in lesional sdkin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 27: 922–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Megna M, Napolitano M, Patruno C, Villani A, Balato A, Monfrecola G, Ayala F, Balato N. Systematic treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: a review. Dermatol Ther 2017; 7: 1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Cotter DG, Schairer D, Eichenfield L. Emerging therapies for atopic dermatitis: JAK inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; December 14. pii: S0190-9622(17)32820-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.019. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Hajar T, Hanifin JM. New and developing therapies for atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol 2018; 93: 104–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Calzavara Pinton P, Cristaudo A, Foti C, et al. Diagnosis and management of moderate to severe adult atopic dermatitis: a consensus by the Italian Society of Dermatology and Venereology (SIDeMaST), the Italian Association of Hospital Dermatologists (ADOI), the Italian Society of Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology (SIAAIC), and the italian Society of Allergological, Environmental and Occupational Dermatology (SIDAPA). G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2018; 153: 133–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Krutmann J Phototherapy for atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000; 25: 552–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Morrison WL, Parrish JA, Fitzpatrick TB. Oral psoralen photochemotherapy of atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol 1978; 98: 25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Krutmann J, Czech W, Diepgen T, Niedmer R, Kapp A, Schopf E. High dose UVA1 therapy in the treatment of patients with atopic eczema. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26: 225–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).York NR, Jacobe HT. UVA1 phototherapy: a review of mechanism and therapeutic application. Int J Dermatol 2010; 49: 623–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Breuckmann F, von Kobyletzki G, Radenhausen M, et al. Mechanisms of apoptosis: UVA1 induced immediate and UVB induced delayed apoptosis in human T cells in vitro. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003; 17: 418–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Krutmann J, Diepgen TL, Luger TA et al. High dose UVA1 therapy for atopic dermatitis: results of a multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38: 589–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Kowalzick L, Kleinheinz A, Weichenthal M et al. Low dose versus medium dose UVA1 treatment in severe atopic eczema. Acta Derm Venereol 1995; 75: 43–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Tzaneva S, Seeber A, Schwaiger M et al. High dose versus medium dose UVA1 phototherapy for patients with severe generalized atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 45: 503–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Kroft EB, van de Kerkhof PC, Gerritsen MJ, et al. Period of remission after treatment with UVA-1 in sclerodermic skin diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22: 839–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Calzavara-Pinton P, Monari P, Manganoni AM, Ungari M, Rossi MT, Gualdi G, Venturini M, Sala R. Merkel cell carcinoma arising in immunosuppressed patients treated with high-dose ultraviolet A1 (320-400) phototherapy: a report of two cases. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2011; 26: 263–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Van Weelden H, van der Putte SC, Toonstra J, van der Leun JC. UVA induced tumors in pigmented hairless mice and the carcinogenic risks of tanning with UVA. Arch Dermatol Res 1990; 282: 289–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Setlow RB, Grist E, Thompson K, Woodhead AD. Wavelengths effective in induction of malignant melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 6666–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Wang SQ, Setlow R, Berwick M, et al. Ultraviolet A and melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44: 837–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Nathan R, York BS, Jacobe HT. UVA1 phototherapy: a review of mechanism and therapeutic application. Int J Dermatol 2010; 49: 623–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 1980; 92: 44–7 [Google Scholar]

- 28).Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labreze L, Stalder JF, Ring J, Taieb A. Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index: consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 1997; 195: 10–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Krutmann J High dose ultraviolet A1 (UVA1) phototherapy: does it work? Photodermatol Photimmunol Photomed 1997; 13: 78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Prezzano JC, Beck LA. Long term treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin 2017; 35: 335–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Rombold S, Lobisch K, Katzer K, Grazziotin TC, Ring J & Eberlein B. Efficacy of UVA1 phototherapy in 230 patients with various skin diseases. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2008; 24: 19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Abeck D, Schmidt T, Fesq H, et al. Long term efficacy of medium dose UVA1 phototherapy in atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42: 254–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Jacobe HT, Cayce R, Nguyen J. UVA1 phototherapy is effective in darker skin: a review of 101 patients of Fitzpatrick ski type I-V. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 691–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Kollias N, Sayre RM, Zeise L, Chedekel MR. Photoprotection by melanin. J Photochem Photobiol B 1991; 9: 135–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Thody AJ, Higgins EM; Wakamatsu K, Ito S, Burchill SA, Marks JM. Pheomelanin as well as eumelanin is present in human epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 1991; 97: 340–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Chedekel MR, Poh Agin P, Sayre RM. Photochemistry of pheomelanin: action spectrum for superoxide production. Photochem Photobiol 1980; 31: 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Picardo M, Maresca V, Eibenschutz L, Bernardo De C, Rinaldi R, Grammatico P. Correlation between antioxidants and phototypes in melanocytes cultures. A possible link of physiologic and pathologic relevance. J Invest Dermatol 1999; 113: 424–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Fitzpatrick TB. Ultraviolet-induced pigmentary changes: benefits and hazards In: Current problems in Dermatology; vol. 15 Basel: Karger, 1986; 25–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Moyal D Prevention of ultraviolet induced skin pigmentation. Photodermatol Photimmunol Photomd 2004, 20: 243–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Seite S, Moyal D, Richard S, et al. Effects of repeated suberythemal doses of UVA in human skin. Eur J Dermatol 1997; 7: 203–9 [Google Scholar]

- 41).Young AR. The molecular and genetic effects of ultraviolet radiation exposure on skin In: Hawk JLM, ed Photodermatology: London: Aenold, 1999: 25–42 [Google Scholar]

- 42).Gilchrest BA, Park HY, Eller MS, Yaar M. Mechanisms of ultraviolet light induced pigmentation. Photochem Photobiol 1996; 63: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Chardon A, Moyal D, Hourseau C. Persistent pigment darkening response as a method for evaluation of ultraviolet A production assays In: Lowe NJ, Shaath NA, Pathak MA, eds. Sunscreens: development, evaluation and regulatory aspects. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1997: 559–82 [Google Scholar]

- 44).Routaboul C, Denis A, Vinche A. Immediate pigment darkening: description, kinetic and biological function. Eur J Dermatol 1999; 9: 95–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]