Abstract

Background:

Research on women with substance use disorders has expanded, yet knowledge and implementation gaps remain.

Methods:

Drawing from topics discussed at the 2017 meeting of InWomen’s in Montreal, Canada, this article reviews key progress in research on substance use among women, adolescents, and families to delineate priorities for the next generation of research.

Results:

The field has seen significant accomplishments in multiple domains, including the management of pregnant women with substance use and comorbid psychiatric disorders, caring for neonates in opioid withdrawal, greater inclusion of and treatment options for LGBTQ+ communities, gendered instrumentation, and gender-focused HIV interventions for adolescent girls and women. Women who use alcohol and other drugs often experience other comorbid medical conditions (hepatitis C virus and HIV), contextual confounders (intimate partner violence exposure, homelessness, trauma), and social expectations (e.g., as caretakers) that must be addressed as part of integrated care to effectively treat women’s substance use issues. Although significant advances have been made in the field to date, gender-based issues for women remain a neglected area in much of substance abuse research. Few dedicated and gender-focused funding opportunities exist and research has been siloed, limiting the potential for collaborations or interdisciplinary cross-talk.

Conclusion:

Given renewed attention to substance use in the context of the burgeoning opioid epidemic and shifts in global politics that affect women’s substance use, the field requires a strategic rethink to invigorate a pipeline of future research and researchers.

Keywords: Substance use research, Gender, Women, Substance use disorders

1. Introduction

Globally, substance use is gendered. Twice as many men as women, for example, have substance use disorders (SUDs) involving licit and illicit substances in a way that is clinically and functionally impairing (SAMHSA;, 2018). However, women increase their rate of drug consumption more rapidly than men once they initiate drug use, and they experience more negative health and social consequences (Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators, 2016; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2017). In the United States, the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed that 45% of people aged 12 or older who use illicit drugs are women (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017). Although one in three people with SUDs is a woman, only one of five people in substance abuse treatment is a woman, which implies gender-specific barriers to treatment access and engagement (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2015).

Early addiction research demonstrated treatment disparity, where women were virtually excluded (Blume, 1986; Weisner and Schmidt, 1992); consequently, the effectiveness of treatment in women was unknown. Research has since emerged highlighting the impact of gender on substance use in terms of health and social effects, and treatment (Greenfield et al., 2007). While some issues crosscut gender, existing data support gender-informed SUD prevention and treatment strategies to increase cultural relevance, efficacy, and effectiveness (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015).

Most existing addiction research is male oriented. For example, across 24 studies in the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network, less than half of participants were women (Korte et al., 2011) and just three interventions were women-specific (Greenfield et al., 2011). Subsequently, in 2015, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) began requiring all funded research to account for sex as a biological variable through study design, analysis, data interpretation, and reporting of results (National Institutes of Health, 2015). These advances in NIH policy coincided with sweeping health policy reforms, including the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act signed by President Obama in July 2016 that expanded access to critical SUD treatment programs and overdose prevention services. Within these progressive policies, however, women-specific services were limited to expanding treatment programs for pregnant and postpartum women (United States Congress, 2016). Although much has been achieved in understanding the perinatal and postnatal effects of SUD through focused research, overall these topics do not treat women as persons who need treatment.

Despite many significant achievements in research and policy, work remains to be done in the field of women who use alcohol or other drugs (WWUD). For example, although the increasing mortality caused by opioid overdose, including among women, has led to official acknowledgement that opioid abuse represents a public health emergency and was accompanied by dedicated funding to address the epidemic, resources have been channeled mostly toward law enforcement to reduce drug supply and toward the development of non-opioid treatments for pain (The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, 2017). Missing from this agenda is expansion of harm-reduction services or treatment for women’s comorbid medical, psychiatric, and social conditions—including HIV, hepatitis C, depression, trauma, and homelessness—or acknowledgement of the importance of gender in the context of substance use. For instance, women often benefit from collaborative case management, but these services are rarely available in SUD treatment centers (SAMHSA, 2017). Evidence-based strategies for WWUD are urgently needed (International Narcotics Control Board, 2017; Office on Women’s Health, 2017).

In this article, we present key research and implementation gaps related to substance use in women, adolescents and families to help guide priorities for the next generation of research. In doing so, this paper highlights specific areas that require dedicated and adequately supported research. This is not intended to be an exhaustive systematic or scoping review, but rather to broadly address critical issues, with exemplary references, raised in an expert discussion at the 2017 InWomen’s Conference in Montreal, Canada.

2. The InWomen’s Network

More than 10 years ago, a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) official approached Dr. Wendee Wechsberg about forming a group of researchers, students, and interested government officials to focus on women’s issues in substance use. The resulting International Women’s and Children’s Health and Gender Group (InWomen’s) is dedicated to promoting evidence-based research in the field of substance use as it relates to gender, women and children (Wechsberg, 2012). The mission of the InWomen’s network is to share new and significant findings about the consequences of substance use and risk behaviors; identify and promote innovative research that helps to empower women across the lifespan; foster gender-based analyses in research; raise awareness about the need for sensitivity in research to family, culture, sexual orientation, and equity within an international context; promote the benefits of prevention, intervention, and treatment; forge new collaborations and develop research agendas. Consistent with NIDA’s research agenda, InWomen’s focus encompasses all types of substance use (both licit and illicit) that affect women and families.

The InWomen’s multidisciplinary network began meeting virtually and then in-person in the first annual meeting in 2007. It now comprises more than 200 members from over 40 countries worldwide. Members of the InWomen’s network have compiled a list of bibliographic references with accompanying short summaries of seminal articles in the field of substance use related to women, children, youth, LGBTQ+, and gender differences around the world. In the first year of the project, established researchers in the network were asked to recommend key papers, and the file has been updated by all network members annually ever since. This annotated bibliography consists of over 1,000 references, with approximately 120 new articles added in 2017. The bibliography is sorted into 11 topic headings: Adolescent Drug Abuse; Drug and Alcohol Abuse; Family Issues; Gender Differences; HIV and Women; Interpersonal Violence and Trauma; Justice-Involved Women; LGBTQ Issues; Pregnancy and Postpartum; Trafficking and Sex Workers; and Women-Focused Treatments and Interventions. The full bibliography is publicly available at the InWomen’s wiki site: www.tinyurl.com/InWomen-Annotated-Bib. Over time, there has been increasing attention to management of pregnant women with substance use and comorbid psychiatric disorders, caring for neonates in opioid withdrawal, greater inclusion of and treatment options for LGBTQ+ communities, gendered instrumentation, and gender-focused HIV interventions for adolescent girls and women. Accordingly, the bibliography is sorted by year of contribution.

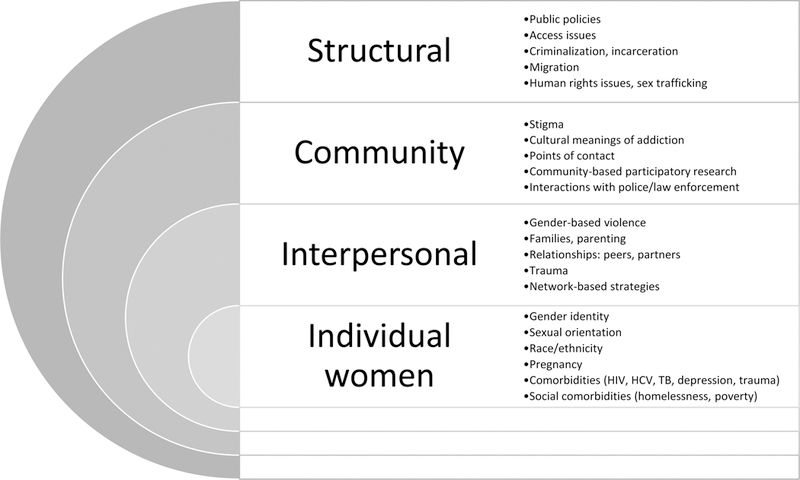

At the 10th annual meeting of the InWomen’s group in Montréal in June 2017, discussions were organized around some of the major topics in the annotated bibliography. In one discussion, a multidisciplinary, multi-institutional, multicultural team of global experts on women and addiction addressed future directions for research. This article summarizes the principal findings from that discussion. Key concepts are organized along a socioecological framework, which proposes that health is impacted by individual-level, interpersonal, community-level, systems-level and structural factors (Figure 1) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Consistent with a patient-centered approach, individual women remain at the core, but a broader focus acknowledges that women do not experience substance use in isolation, requiring multilevel strategies to improve health. A socioecological framework was selected because it encompassed multiple perspectives on any topic, for example, “Trafficking and sex workers” includes: 1) approaches to individual women as sex workers, 2) network-based interpersonal strategies, 3) stigmatization by communities, and 4) structural human rights issues. Accordingly, information about each of the 11 topics in the InWomen’s annotated bibliography was integrated into the socioecological framework for discussion. A systematic review was beyond the scope of this paper; example references are included below but more extensive literature can be found in the annotated bibliography or through database searches (e.g. PubMed, Medline).

Figure 1.

Priority focus areas for research on women with substance use disorders, by socioecological factors

3. Knowledge Gaps to Be Addressed by Future Research

3.1. Individual-level factors

As shown in Figure 1, individual-level factors affecting women’s substance use outcomes include women’s identities related to gender and race/ethnicity, pregnancy, and medical, psychiatric, and social comorbidities. Women’s substance use and their treatment needs are heterogeneous, and research is needed on important subpopulations to inform meaningful interventions. Historically, research on women has focused on alcohol and prescription opioids as primary substances of use among women and of major interest in terms of impact on the fetus in pregnancy (SAMHSA;, 2014). Yet, a more granular approach is needed to understand the specific impact of various forms of substance use—including opioids, methamphetamines, alcohol, marijuana, e-cigarettes, and polysubstance use—on diverse groups of WWUD, including women who experience intersectional stigma by engaging in sex work or identifying as cultural or class minorities. As substance use trends and drug policy change over time, opioid injection, e-cigarettes, and marijuana use are emerging as major issues affecting women’s lives, requiring dedicated research and prevention and treatment approaches (Health;, 2016).

At the individual level, it will be necessary to broaden concepts of gender identity and sexual orientation, describing major barriers to treatment engagement among WWUD who identify as LGBTQ+ (Powell et al., 2018). Appropriate terminology is essential to conscientious research, and although sex is a biological characteristic, gender is an identity. This distinction needs to be clarified in future research because it relates to women’s access and response to treatment.

Additionally, it will be necessary to address stigmatization, awareness, and treatment of substance use in pregnancy (Hammond et al., 2018). A recently proposed policy in the state of Montana to “crack down” on and incarcerate pregnant women who use drugs exemplifies this problem and was met with strong opposition by numerous professional organizations (Associated Press, 2018). Altogether, 24 states and the District of Columbia consider substance use during pregnancy a reportable child abuse offense (Guttmacher Institute, 2018). Rather than criminalizing substance use behavior, women who are pregnant need priority access to treatment for SUDs, as has been implemented in some US states. Or at a minimum, they need protection from discrimination in SUD treatment programs (Guttmacher Institute, 2018).

In addressing substance use in pregnancy, both biological factors (such as pharmacodynamics of opioid agonist therapies, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and distribution of substances in placenta and breast milk) and sociocultural factors (such as stigmatization of substance use in pregnancy, meanings of motherhood, and access to prenatal, family planning and reproductive health services) need to be considered. There is also a need to better understand the dynamic patterns of women’s substance use across the lifespan, beginning with adolescence.

Individual WWUD often experience co-occurring medical (HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis), psychiatric (depression, trauma), and social (homelessness, poverty) conditions that impact their substance use trajectories and engagement in care (Iversen et al., 2015; SAMHSA;, 2014; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Future research will need to incorporate both behavioral and biomedical strategies to address these comorbidities, such as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for prevention, hepatitis C treatment with newer direct acting antivirals, “housing first” models of interventions for women who experience homelessness, and microfinance strategies to address empowerment and poverty. SUD treatment is a particularly powerful HIV prevention tool for WWUD (Springer et al., 2015). Integrated models of care that incorporate these tools have been shown to be effective (Sabri and Gielen, 2017), but they have often paid minimal attention to gender-specific areas that should be addressed by future research (Wechsberg et al., 2015).

3.2. Interpersonal factors

Women’s substance use is often embedded within personal relationships and many WWUD have overlapping sex and drug use networks that increase their potential exposure to HIV and hepatitis C (El-Bassel, 2012). As compared with men, women more often initiate substance use with a partner and are subsequently more likely to share injecting equipment (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2015). In this relational context of substance use, women are often exposed to intimate partner violence and experience trauma (Devries et al., 2014; Sullivan and Holt, 2008). Consequently, gender-based violence should be a priority focus for research on WWUD. Additionally, trauma-informed treatment approaches are urgently needed, but currently underutilized. On another interpersonal level, in recognizing that WWUD are often mothers, work is needed to assess the impact of substance use on parenting and to develop treatment strategies that acknowledge women as mothers, such as incorporating parenting classes and onsite childcare.

3.3. Community-level factors

Community-level factors also need to be addressed by future research on WWUD. In many areas globally, women’s drug use is highly stigmatized, and women are publicly shamed, deterring them from seeking out or engaging in treatment. The field demands the development of gender specific and culturally sensitive approaches that can identify women who need treatment and engage them in care, while delivering broader public health messages to reduce stigma. This area of work needs to move beyond laboratory and clinical settings and to access women and deliver interventions in places they already interface, such as hair salons, churches, and criminal justice settings. Some productive work in community settings has begun. For example, a scoping review (Meyer et al., 2017) identified 42 separate interventions aimed at reducing HIV risk among women and girls in criminal justice settings, many of whom are WWUD. Similarly, a faith-based HIV intervention for African American women has been successfully implemented in a church (Wingood et al., 2011).

3.4. Systems-level and structural factors

Figure 1 delineates major systems-level barriers to women’s substance use outcomes and treatment engagement, including public policies, access issues, criminalization/incarceration, migration, and human rights issues, including sex trafficking. On a structural level, for example, one must consider the impact of sex trafficking on women’s experiences of substance use. Others have argued that drug policy has a disproportionately negative impact on women and leads to their incarceration (Malinowska-Sempruch and Rychkova, 2015). There are major systems barriers to treatment engagement so policy evaluations are needed to ensure systems are designed to effectively meet women’s treatment needs. A thorough discussion of the development of gender-responsive structural HIV prevention interventions for WWUD has been published elsewhere (Blankenship et al., 2015).

4. Methodological issues

The NIH Policy and Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities mandates the inclusion of women and racial/ethnic minorities in clinical research. Although most researchers are aware of the associated recruitment requirements, the policy was amended in 2017 to clarify the requirement that clinical trials must include “the results of valid analyses by sex/gender and race/ethnicity” (National Institutes of Health, 2017). Although confined to clinical research, the policy is consistent with an impressive body of research demonstrating gender differences in factors, including the process of drug addiction (Elton and Kilts, 2009; Lynch et al., 2009), the pathway to treatment (Grella, 2009), and the probability of acquiring hepatitis C among people who inject drugs (Roman-Crossland et al., 2004). The policy also speaks to issues unique to women, such as substance use during pregnancy, that necessitate a better understanding of women and substance use.

Future research aimed at understanding WWUD will require techniques beyond simply conducting separate analyses for each gender. Few resources are available to guide researchers on conducting valid analyses. Even the standards for qualitative (Levitt et al., 2018) and quantitative (Appelbaum et al., 2018) research methods updated recently in the American Psychologist provide only limited attention to gender. Some researchers argue that valid analyses require attention to both measurement and design/data issues (Burlew et al., 2009).

Further, the American Psychological Association warns against measurement nonequivalence, especially when comparing two groups (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014). Differences in the lived experiences of men and women increase the possibility of measurement nonequivalence. For example, one study demonstrated gender nonequivalence on a subscale of the Internal Barriers to Substance Abuse Treatment that assesses the extent to which stigma is a barrier to treatment (Xu et al., 2007). It would be difficult to determine whether gender differences on that scale are actual or attributable to measurement nonequivalence. However, several strategies—including confirmatory factor analysis, item response theory, and multiple regression—are available to assess and address measurement nonequivalence (Burlew et al., 2009).

In addition to measurement, attention to design and data analysis is important for conducting gender-sensitive research. Steps for adequately addressing gender in research include (1) conducting a preliminary literature review to identify any existing information on the role of gender, (2) including research questions that address the relationship of gender to the study variables, (3) validating measures to ensure measurement invariance, (4) performing a sex disaggregated analysis, (5) clarifying the results for each gender even if preliminary results suggest gender does not directly impact the findings, and (6) discussing any important future research questions on the role of gender (Nieuwenhoven and Klinge, 2010).

Along with these recommendations, other strategies support gender-sensitive research. First, early in the planning stage, researchers should ensure that the research plan matches the intent of the study. Gender comparison designs are appropriate for discerning unique characteristics of women who use drugs, such as time between first use and SUD and treatment-seeking patterns. However, gender-specific (women-only) designs are typically more suitable for addressing questions primarily relevant to women, such as substance use in pregnancy. Within-group designs also may help avoid the trap of treating women as a homogeneous group. A within-group intersectionality approach attends to the multiple identities that women experience, such as race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and immigration status, whereas ignoring these intersecting identities may lead to incorrect conclusions about specific subgroups of women. For example, in a trauma-informed treatment study for women who use substances, women receiving the intervention had better outcomes than women in treatment-as-usual (Amaro et al., 2007). Once race/ethnicity was evaluated as a moderator, however, the results revealed that the treatment was more effective in reducing drug use severity for non-Hispanic Whites than the other racial/ethnic groups, and a subgroup of Hispanic women had better trauma outcomes than any other group. The moderator variable findings identified important subgroup differences that otherwise might have been overlooked in evaluating treatment efficacy.

5. Rethinking Implementation Science and Innovations in Addiction Research for Women

By filling these knowledge gaps and deploying appropriate methodologic strategies, researchers can continue to generate evidence-based interventions that will positively impact the lives of WWUD. From the perspectives of public health and implementation science, women-focused interventions then need to be translated from more controlled field settings that assess efficacy to real-world practice to assess effectiveness. In so doing, packaged interventions need to be adapted to other the cultural milieus.

Additionally, programs need to be developed in a way that is sustainable, despite potential disruptions by changing political climates and local laws. One way to improve both cultural relevance and sustainability of SUD treatment programs is to involve stakeholders and engage in community-based participatory research, following the dictum “Nothing about us without us” (Bell and Salmon, 2011).

Another critical strategy to expanding the impact of interventions, while retaining cultural relevance and improving efficiency, is innovation. For example, harnessing mobile health (mHealth) technology, referring to the use of a mobile phone or tablet to access personal medical data or information tied to an individual’s health condition. mHealth broadly encompasses applications (apps) that can use mobile phones to record vital signs (e.g., heart rate), activity, or body weight through Bluetooth-connected sensors. mHealth apps are also ideal for delivering health information in a micro-learning format, where videos or educational material are designed to be consumed in 3 to 5 minutes at the learner’s own pace (Mayo Clinic Medical Laboratories, 2018). Given that 95% of US adults own a cell phone, 77% of which are smartphones (Pew Research Center Internet and Technology, 2018), a key benefit to micro-learning is that it can be made available at any time or in any location, making it highly suitable for on-the-go or remote learning. Both private employers and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) report significant increases in the funding for telehealth services (Castellucci, 2017). The 21st Century Cures Act also mandated the use of technology in healthcare services and called for more research on connecting rural patients with healthcare providers (Petro, 2017).

To date, there are only two Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved mHealth apps for the treatment of SUDs, called reSET (Campbell et al., 2014) and reSET-O (Christensen et al., 2014). reSET requires a prescription code to be downloaded to a phone and works in tandem with face-to-face healthcare provider visits and contingency management. The reSET app effectively increased rates of abstinence and retention in treatment in clinical trials of individuals with alcohol, marijuana and stimulant SUDs (Campbell et al., 2014; United States Food & Drug Administration, 2018a). In December 2018, the FDA approved reSET-O to increase retention in medication assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorders (Christensen et al., 2014; United States Food & Drug Administration, 2018b). Presently, reSET and reSET-O are the only prescription mobile medical apps for SUD treatment available with a prescription from a medical doctor in the USA. A thorough description and efficacy evaluation of all mobile applications on the market for substance use treatment is beyond the scope of this review article. However, a recent search of Google Play and Apple Stores revealed over 100 mobile applications for specific SUD treatments and educational materials.

In 2017, NIH funded 56 mHealth research studies, several of which included behavioral health services. Some are in trial, with one specifically for young African American women at risk for HIV. To our knowledge, there are no published apps specific to WWUD, but mHealth interventions are potentially powerful tools to reach the 70% of women seeking treatment for SUDs who have children (Brady and Olivia, 2005), women who may not be ready for treatment, or women for whom treatment may not be accessible. In addition to time constraints, these women frequently face stigma, financial, childcare, and transportation issues that prevent them from seeking behavioral health services. Researchers are exploring the use of internet-based psychosocial interventions to reduce substance use, but women-specific programs are still in the validation stages, and uptake has been slow (Marsch and Dallery, 2012). A recent review (Byambasuren et al., 2018) found 22 mobile prescription apps that had been examined for efficacy in 23 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for diabetes, mental health and obesity (illicit substance use was excluded). The majority of these RCTs were under-powered and few completed any long-term follow up. Only three of the 23 RCTs dealt with licit substance use with mixed results and none were women-specific. In the future, apps will need to be developed to help women initiate or link to treatment.

6. Building Capacity for Future Research

For research on WWUD to advance, a pipeline of future experts needs to be adequately trained and supported. For instance, emerging and mid-career investigators will not only need to have opportunities for training, mentorship, and funding to develop careers in the area of women and addiction, they will need active and ongoing support. Ideally, training will need to be multidisciplinary, drawing from the fields of addiction medicine and psychiatry, epidemiology and public health, women’s health, infectious diseases, psychiatry, and trauma. Similarly, a future generation of clinicians will require training in gender-responsive addiction medicine, psychiatry, psychology, and social work to build capacity for treatment and other service provision. All providers, not just addiction specialists, are on the frontline of the burgeoning opioid epidemic and will require adequate training and support to meet treatment demands (Rapoport and Rowley, 2017). For ongoing dedicated researchers in the field, focused and targeted funding opportunities will need to be available to support the development of gender-responsive interventions for WWUD (El-Bassel and Strathdee, 2015).

7. A Proposed Research Agenda

Multiple barriers exist to expanding research in the field of WWUD that will need to be addressed by a comprehensive research agenda. First, limited training opportunities exist for the next generation of researchers to develop niches in the area of women and addiction. Rapid expansion in the number of accredited fellowships in addiction medicine and psychiatry will help support the next generation of trained clinicians, although none of the existing training programs specifically addresses women’s health. Second, the fact that there are few dedicated funding opportunities deters new and mid-level investigators from entering the field, which further restricts the pool of qualified grant reviewers with necessary expertise. Third, few global conference opportunities exist dedicated to WWUD in which scientists can feature their work and develop collaborations to move the field forward.

These issues compound a challenging political climate that prioritizes criminalizing substance use, rather than preventing, identifying, and treating it. Women’s issues relating to substance use are complex and heterogeneous, requiring multidisciplinary approaches to develop effective, integrated systems and interventions tailored to women’s specific needs.

To guide the development of funding opportunities and help drive the field forward we propose a realignment of research priorities such as the following:

Address the impact of substance use on key subpopulations of women, including women who identify as LGBTQ+ or gender-nonconforming and cultural minorities.

Focus on the specific needs of women of childbearing age, including treatment of SUDs during and following pregnancy, and access to reproductive health and family planning services.

Address the heterogeneity of substance use among women in both treatment and research, incorporating differences by substances used, race/ethnicity, or gender identity.

Develop SUD treatment strategies that are trauma-informed and/or address the impact of gender-based violence on substance use.

Develop SUD treatment strategies that recognize the role of women as caregivers or parents.

Develop substance use prevention and treatment strategies that are relational or network-based and evaluate the impact of women’s substance use on peers, partners, parenting, or communities.

Use community-based participatory research methods to design substance use prevention and treatment strategies for women that are culturally meaningful and sustainable.

Address structural influences on women’s engagement in services for SUDs, including (but not limited to) sex trafficking, migration, and involvement in the criminal justice system.

Use mHealth technologies to develop flexible outreach, screening and treatment services for women with SUDs.

Evaluate the impact of public policy and law on women’s access to treatment services for SUDs.

Acknowledgements

This article originated from a discussion of attendees at the 10th Annual International Women’s and Children’s Health and Gender Group held June 16, 2017, in Montréal, Canada. We would like to acknowledge the contributions from the following InWomen’s members in conceptualizing the issues: Pavla Dolezalova, Gary Zarkin, Sam Freedman, Lorraine Milio, and Tatiana Keiazova. We also acknowledge the support from the RTI Global Gender Center and its support of the conference and this article, and we thank Jeffrey Novey for editorial support.

Role of funding source

The funding source played no role in the design, analysis, interpretation of data, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of RTI International, Inc.

Funding: The work was supported by the RTI Global Gender Center, RTI International. Research Triangle Park, NC.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Amaro H, Dai J, Arévalo S, Acevedo A, Matsumoto A, Nieves R, Prado G, 2007. Effects of Integrated Trauma Treatment on Outcomes in a Racially/Ethnically Diverse Sample of Women in Urban Community-based Substance Abuse Treatment. J Urban Health 84, 508–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, 2014. Standards for educational and psychological testing In: AERA; (Ed.), Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum M, Cooper H, Kline RB, Mayo-Wilson E, Nezu AM, Rao SM, 2018. Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am Psychol 73, 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Associated Press, 2018. Groups Condemn Attorney’s Crack Down on Pregnant Drug Use https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/montana/articles/2018-01-18/groups-condemn-attorneys-crack-down-on-pregnant-drug-use. accessed on March 3 2018>.

- Bell K, Salmon A, 2011. What Women Who Use Drugs Have to Say about Ethical Research: Findings of an Exploratory Qualitative Study. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 6, 84–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KM, Reinhard E, Sherman SG, El-Bassel N, 2015. Structural Interventions for HIV Prevention Among Women Who Use Drugs: A Global Perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69 Suppl 2, S140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume SB, 1986. Women and alcohol. A review. Jama 256, 1467–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady T, Olivia A, 2005. Women in Substance Abuse Treatment: Results from the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS). In: Substance Abuse and Mental health Services Administration, O.o.A.S; (Ed.), Rockville. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, 1979. The ecology of human development. American Psychology 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar]

- Burlew AK, Feaster D, Brecht ML, Hubbard R, 2009. Measurement and Data Analysis in Research Addressing Health Disparities in Substance Abuse. J Subst Abuse Treat 36, 25–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byambasuren O, Sanders S, Beller E, Glasziou P, 2018. Prescribable mHealth apps identified from an overview of systematic reviews. npj Digital Medicine 1, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AN, Nunes EV, Matthews AG, Stitzer M, Miele GM, Polsky D, Turrigiano E, Walters S, McClure EA, Kyle TL, Wahle A, Van Veldhuisen P, Goldman B, Babcock D, Stabile PQ, Winhusen T, Ghitza UE, 2014. Internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 171, 683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci M, 2017. Telehealth drives up healthcare utilization and spending http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20170307/NEWS/170309914. accessed on March 11 2018>.

- Christensen DR, Landes RD, Jackson L, Marsch LA, Mancino MJ, Chopra MP, Bickel WK, 2014. Adding an Internet-delivered treatment to an efficacious treatment package for opioid dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol 82, 964–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Child JC, Bacchus LJ, Mak J, Falder G, Graham K, Watts C, Heise L, 2014. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 109, 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA, 2015. Women Who Use or Inject Drugs: An Action Agenda for Women-Specific, Multilevel, and Combination HIV Prevention and Research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69 Suppl 2, S182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Wechsberg WM, Shaw SA, 2012. Dual HIV risk and vulnerabilities among women who use or inject drugs: no single prevention strategy is the answer. Current Opinioin in HIV & AIDS 7, 326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elton E, Kilts C, 2009. The Roles of Sex Differences in the Drug Addiction Process In: Brady K, B. S, and Greenfield S (Ed.), Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators, 2016. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388, 1603–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Hien D, Miele GM, 2007. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend 86, 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Rosa C, Putnins SI, Green CA, Brooks AJ, Calsyn DA, Cohen LR, Erickson S, Gordon SM, Haynes L, Killeen T, Miele G, Tross S, Winhusen T, 2011. Gender research in the National Institute on Drug Abuse National Treatment Clinical Trials Network: a summary of findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 37, 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella C, 2009. Treatment Seeking and Utilization among women with substance use disorders. In: Brady K, B. S, and Greenfield S (Ed.), Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute, 2018. Substance Use During Pregnancy https://www.guttmacher.org/print/state-policy/explore/substance-use-during-pregnancy. accessed on May 21 2018>.

- Hammond A, Collier K, Terplan M, Chisolm M, 2018. Management of pregnant women with comorbid substance use disorders and other psychiatric illness. College of Problems on Drug Dependence, InWomen’s Symposium, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Health;, O.o.W.s., 2016. White Paper: Opioid Use, Misuse, and Overdose in Women https://www.womenshealth.gov/files/documents/white-paper-opioid-508.pdf. accessed on January 8 2019>.

- International Narcotics Control Board, 2017. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2016 In: Nations, U; (Ed.), New York. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen J, Page K, Madden A, Maher L, 2015. HIV, HCV, and Health-Related Harms Among Women Who Inject Drugs: Implications for Prevention and Treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69 Suppl 2, S176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte JE, Rosa CL, Wakim PG, Perl HI, 2011. Addiction treatment trials: how gender, race/ethnicity, and age relate to ongoing participation and retention in clinical trials. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2, 205–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, Frost DM, Josselson R, Suárez-Orozco C, 2018. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist 73, 26–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch W, Potenza M, Cosgrove K, Mazure C, 2009. Sex Differences in vulnerability to Stimulant Use. In: Brady K, S.B., and Greenfield S (Ed.), Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska-Sempruch K, Rychkova O, 2015. The Impact of Drug Policy on Women In: Foundations, O.S. (Ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Dallery J, 2012. Advances in the psychosocial treatment of addiction: the role of technology in the delivery of evidence-based psychosocial treatment. The Psychiatric clinics of North America 35, 481–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic Medical Laboratories, 2018. Microlearning: All the Small Things https://www.medpagetoday.com/mayo/article/500499. accessed on May 21 2018>.

- Meyer JP, Muthulingam D, El-Bassel N, Altice FL, 2017. Leveraging the U.S. Criminal Justice System to Access Women for HIV Interventions. AIDS Behav 21, 3527–3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health, 2015. NOT-OD-15–102: Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in NIH-funded Research https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-102.html. accessed on May 30 2018>.

- National Institutes of Health, 2017. NOT-OD-18–014: Amendment: NIH Policy and Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-18-014.html. accessed on May 30 2018>.

- Nieuwenhoven L, Klinge I, 2010. Scientific excellence in applying sex- and gender-sensitive methods in biomedical and health research. Journal of women’s health (2002) 19, 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office on Women’s Health, 2017. Final Report: Opioid Use, Misuse, and Overdose in Women In: Services, U.S.D.o.H.a.H (Ed.), Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Petro L, 2017. Telehealth to the Forefront in 2017: 21st Century Cures Act https://www.natlawreview.com/article/telehealth-to-forefront-2017-21st-century-cures-act. accessed on March 11 2018>.

- Pew Research Center Internet and Technology, 2018. Mobile Fact Sheet http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/. accessed on March 3 2018>.

- Powell C, Stevens S, Korchmaros J, Ellasante I, 2018. A Global Perspective on LGBTQ+ Substance Use, Treatment, and Gaps in Research College of Problems on Drug Dependence, InWomen’s Symposium, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport AB, Rowley CF, 2017. Stretching the Scope — Becoming Frontline Addiction-Medicine Providers. New England Journal of Medicine 377, 705–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Crossland R, Forrester L, Zaniewski G, 2004. Sex differences in injecting practices and hepatitis C: A systematic review of the literature In: Report, C.C.D (Ed.). pp. 125–132. [PubMed]

- Sabri B, Gielen A, 2017. Integrated Multicomponent Interventions for Safety and Health Risks Among Black Female Survivors of Violence: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse, 1524838017730647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- SAMHSA, 2017. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2016 Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. BHSIS Series S-93, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA;, 2014. Gender Differences in Primary Substance of Abuse Across Age Groups. Treatment Episode Data Set: The TEDS Report [PubMed]

- SAMHSA;, 2018. Age- and Gender-Based Populations https://www.samhsa.gov/specific-populations/age-gender-based. accessed on January 8 2019>.

- Springer SA, Larney S, Alam-Mehrjerdi Z, Altice FL, Metzger D, Shoptaw S, 2015. Drug Treatment as HIV Prevention Among Women and Girls Who Inject Drugs From a Global Perspective: Progress, Gaps, and Future Directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69 Suppl 2, S155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015. TIP 51: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women. In: Services, U.S.D.o.H.a.H. (Ed.), Treatment Improvement Protocol, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017. 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health In: Quality, C.f.B.H.S.a. (Ed.), Rockville, Maryland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Holt LJ, 2008. PTSD symptom clusters are differentially related to substance use among community women exposed to intimate partner violence. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21, 173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, 2017. Final Report.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2015. World Drug Report 2015 In: Nations, U; (Ed.), New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2017. World Drug Report 2017: Global overview of drug demand and supply In: publication, U.N. (Ed.). [Google Scholar]

- United States Congress, 2016. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act In: States, U; (Ed.), PL 114–198. [Google Scholar]

- United States Food & Drug Administration, 2018a. Mobile Medical Applications https://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm. accessed on January 8 2019>.

- United States Food & Drug Administration, 2018b. Press Announcements - FDA clears mobile medical app to help those with opioid use disorder stay in recovery programs News & Events; https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm628091.htm. accessed on January 8 2019>. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, 2012. Promising international interventions and treatment for women who use and abuse drugs: focusing on the issues through the InWomen’s Group. Subst Abuse Rehabil 3, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Deren S, Myers B, Kirtadze I, Zule WA, Howard B, El-Bassel N, 2015. Gender-Specific HIV Prevention Interventions for Women Who Use Alcohol and Other Drugs: The Evolution of the Science and Future Directions. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 69, S128–S139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Schmidt L, 1992. Gender disparities in treatment for alcohol problems. Jama 268, 1872–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, Simpson-Robinson L, Braxton ND, Raiford JL, 2011. Design of a faith-based HIV intervention: successful collaboration between a university and a church. Health promotion practice 12, 823–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wang J, Rapp RC, Carlson RG, 2007. The Multidimensional Structure of Internal Barriers to Substance Abuse Treatment and Its Invariance Across Gender, Ethnicity, and Age. J Drug Issues 37, 321–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]