Abstract

Background:

This study examined the impact of a tobacco-free grounds (TFG) policy and the California $2.00/pack tobacco tax increase on tobacco use among individuals in residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment.

Methods:

We conducted three cross-sectional surveys of clients enrolled in three residential SUD treatment programs. Wave 1 (Pre-TFG) included 190 clients, wave 2 (post-TFG and pre-tax increase) included 200 clients, and wave 3 (post-tax increase) included 201 clients. Demographic and tobacco-use characteristics were first compared between waves using bivariate comparisons. Regression models were used to compare each outcome with survey wave as the predictor, while adjusting for demographic characteristics and nesting of participants within programs.

Results:

Odds of clients being current smokers was lower (AOR=0.43, 95%CI = 0.30,0.60) after implementation of TFG compared to baseline. Adjusted mean ratio (AMR) for cigarettes per day was lower post-TFG compared to baseline (AMR=0.70, CI=0.59, 0.83). There were no differences, across waves, in tobacco-related knowledge, attitudes, or services received by program clients, or use of nicotine replacement therapy. Increased cigarette taxation was not associated with reductions in client smoking.

Conclusion:

Implementation of a TFG policy was associated with a lower prevalence of client smoking among individuals in residential SUD treatment. Increased state cigarette excise taxes were not associated with a further reduction in client smoking in the presence of TFG policies, though this may have been confounded by relaxing of the TFG policy. SUD treatment programs should promote TFG policies and increase tobacco cessation services for clients.

Keywords: Tobacco, Drug Treatment, Tobacco-Free Policy, Taxation, Tax, California

1. Introduction

The prevalence of cigarette smoking among adults in the United States (U.S.) has decreased from 40% in 1964 to 15.5% in 2016 (Jamal et al., 2018; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2014). However, smoking prevalence remains high among certain subgroups, including those with serious psychological distress (Jamal et al., 2018). In the U.S., approximately 40% of all cigarettes are smoked by individuals with mental health, alcohol, or drug use diagnoses (Lasser et al., 2000; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2013). Tobacco companies have specifically targeted these populations (Apollonio and Malone, 2005), and tobacco control efforts are needed to counteract these influences (Brown-Johnson et al., 2014). To address these disparities in smoking prevalence, policies and services are needed in behavioral health and drug abuse treatment programs (Compton, 2018).

Individuals in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment are particularly vulnerable to tobacco use. Among clients surveyed in a U.S. national sample of 24 SUD treatment programs, smoking prevalence was 77.9% (Guydish et al., 2016b). In addition to having higher smoking rates compared to the general population, individuals with SUDs are also heavier smokers (Richter et al., 2002) and less successful in quitting smoking than general population smokers (Ferron et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2013). Individuals in SUD treatment are more likely to die from tobacco-related diseases compared to the general population (Bandiera et al., 2015; Hurt et al., 1996). For example, (Callaghan et al., 2018) extracted discharge records for all patients hospitalized in California (1990-2005) and matched them to death records. They found that among hospital discharges reporting drug or alcohol use disorders, 36-49% of all deaths were attributable to smoking-related diseases. In comparison, 17-21% of all deaths in the U.S. in 2004 were attributable to smoking (Fenelon and Preston, 2012).

Many clients in SUD treatment are interested in quitting smoking. About 10% of clients quit smoking while in SUD treatment even in the absence of specific tobacco cessation interventions (Chun et al., 2009; Kohn et al., 2003). McClure et al. (2014) reported that 29% of SUD treatment clients were thinking of quitting smoking within the next 30 days. Quitting smoking, or participating in smoking cessation programs while in SUD treatment, have been found to either have a positive impact or no impact on SUD treatment outcomes (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2014; McKelvey et al., 2017; Thurgood et al., 2016). Quitting smoking may have some benefits to recovery. For example, Weinberger et al., (2017) reported greater odds of substance use relapse among smokers with SUDs who continue to smoke.

Tobacco-free grounds (TFG) policies, which restrict the use of any tobacco products on program property (indoor or outdoor), may help reduce smoking in SUD programs. Currently, one-third of SUD treatment programs in the U.S. have restricted smoking policies on program grounds and there has been an increase in the prevalence of SUD treatment programs that offer smoking cessation services (Cohn et al., 2017; Marynak et al., 2018; Muilenburg et al., 2016; Shi and Cummins, 2015; SAMHSA, 2017). Tobacco-free grounds in the workplace, behavioral health care setting and college campus are often accompanied by an increase in tobacco cessation services offered to clients and staff (Correa-Fernandez et al., 2017; Hahn et al., 2012; Seidel et al., 2017) with the goal of increasing the use of these services to promote tobacco cessation. Providing tobacco-cessation services to clients and staff is an important component when implementing a TFG policy. Making smoking cessation care part of usual treatment has been identified as an important strategy to increase utilization of smoking cessation services and to reduce client and staff smoking in substance use disorder treatment settings (Skelton et al., 2018).

In addition to TFG policies, taxation may also promote tobacco cessation among individuals in SUD treatment. Among the general population, taxation is considered an effective intervention to reduce use of tobacco products (Lynch and Bonnie, 1994; Lewit, 1982; Warner, 1984). However, little is known about the impact tobacco of tax increases on subpopulations of established smokers, such as individuals with SUDs. In 2016, California voters passed Proposition 56, mandating a $2.00 per pack tax increase on cigarettes with equivalent increases on other tobacco products. Effective on April 1, 2017, this tax increased the average price of a pack of cigarettes in California from $5.47 to $7.47 (Henriksen et al., 2017). An increase in the average price of cigarettes may help to promote smoking cessation among economically disadvantaged communities that have the highest rates of smoking (Chaloupka et al., 2012). It has been argued that tobacco price increases are a regressive tax, which results in a greater burden on lower-income individuals (Bader et al., 2011). However, low-income smokers appear to respond to tobacco price increases similarly to the general population, by decreasing smoking prevalence and decreasing cigarette consumption (Bader et al., 2011).

Both TFG policies and cigarette tax increases may reduce smoking in high-risk populations, including individuals receiving SUD treatment. Cross-sectional surveys were done pre and post implementation of a TFG policy in three residential SUD treatment programs. Associations of the TFG policy with client smoking prevalence, tobacco-related attitudes and services were examined. The California tobacco tax increase occurred 4 months after implementation of the TFG policy and we conducted a third cross-sectional survey to explore whether additional changes in smoking behavior were associated with the tobacco-tax increase.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

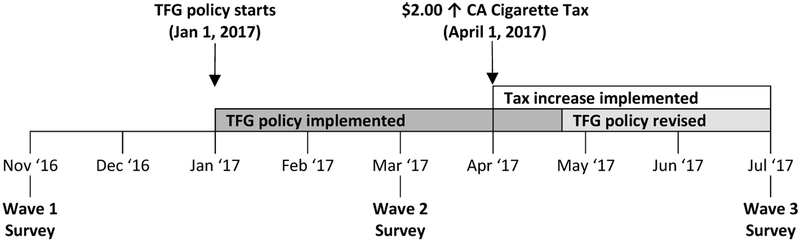

This study surveyed clients from three residential SUD treatment programs located in San Francisco, CA. These included a men’s only program (115 beds), a women-focused program (64 beds), and a mixed gender dual diagnosis program (73 beds). The dual diagnosis program, although mixed gender, primarily consisted of men (78%), and as of June 2017 became a men’s only program. Clients in these programs were surveyed in November 2016 (wave 1, pre-TFG), which was 2 months before TFG implementation. Prior to implementation of the TFG policy, clients were able to smoke outdoors on program property. This meant that clients usually smoked in program entry and exit areas (external porches and stairways), and in program parking lots. One program had an internal open-air courtyard that was used for smoking. After TFG was implemented, on January 1, 2017, clients were prohibited from using all tobacco products (including e-cigarettes) on program property (see Figure 1). This meant that clients had to go farther from the program in order to smoke, for example, onto public sidewalks around the program, or into public parks near the program. The policy did not require clients to quit smoking; however, it made smoking more difficult because “smoke-breaks” from program grounds required more time and effort. Clients were surveyed a second time in March 2017 (wave 2, post-TFG and pre-tax increase), approximately 3 months after implementation of the TFG policy. Clients were surveyed a third time in July 2017 (wave 3, post-tax increase), which was 3 months after California increased the cigarette excise tax from 0.87 to $2.87/pack. Between waves 2 and 3, programs revised the TFG policy to allow clients to take supervised walks three times a day where clients could leave program grounds to smoke. In discussion with directors, we learned that between waves 2 and 3 (pre vs. post tobacco tax increase) staff began incorporating three smoke breaks both on and off program grounds (one after every meal) throughout the day.

Figure 1.

Wave 1 = baseline assessment, prior to implementation of the TFG policy or increase in the CA tobacco tax. Wave 2 = post implementation of the TFG policy, prior to the increase in the CA tobacco tax. Wave 3 = post implementation of the TFG policy and post increase in the CA tobacco tax. * Between waves 2 and 3, programs revised the TFG policy to allow clients to take supervised walks three times a day where clients could leave program grounds to smoke.

2.2. Participants

Survey data collection occurred during site visits to each program at each wave. Site visits took 1 – 2 days and all clients present in the program on these days were eligible to complete the survey. Across all data collection waves, a total of 8 clients declined to participate in the survey during the consent procedures (n wave 1 = 4, n wave 2 = 0, n wave 3 = 4). Clients from the three residential SUD programs were surveyed on three separate occasions. The program director reported the total client census for each program at each site visit.

2.3. Measures

Survey items included demographic information (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, length of time in their current program (weeks in current program), and primary drug for which the client sought treatment (coded as alcohol, stimulants, opiates, or other drug). Race/ ethnicity categories were coded as non-Hispanic White, African American, Hispanic/ Latino, or multiracial/ other). Education was coded as less than a high school education, high school or GED equivalent, or greater than a high school education.

Participants were asked “do you currently smoke cigarettes?” with the response options “Yes, I currently smoke”, “No, I quit smoking”, and “No, I have never smoked”. Responses were used to characterize participants as current, former, or never smokers, respectively. Expired breath carbon monoxide (CO), measured using the handheld piCO+ Smokerlyzer® (Bedfont Scientific, England, UK), was used to verify non-smoking status (i.e., former or never cigarette smokers). Across all survey waves, most self-reported non-smokers (92.9%) had an expired breath CO level less than 6 ppm. Non-smokers with an expired breath CO level greater than 6 ppm (n wave 1 = 0, n wave 2 = 6, n wave 3 = 7) were reclassified as current smokers for the analyses (Middleton and Morice, 2000).

Current smokers reported the number of cigarettes smoked per day and time to first cigarette after waking. Time to first cigarette was used as a measure of nicotine dependence (Baker et al., 2007). Smokers were also asked whether they made a quit attempt in the past year lasting at least 24 hours (yes/no), whether they ever used nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or non-NRT tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy in their lifetime (yes/no), if they were thinking of quitting smoking in the next 30 days (yes/ no), and if they had reduced their smoking due to program requirements, with responses “not at all” and “a little” coded as no, and “somewhat” and “a lot” coded as yes.

Respondents also completed the Smoking Knowledge Attitudes and Services (S-KAS) survey (Guydish et al., 2011) that includes three subscales reflecting: (1) attitudes towards quitting smoking, (2) tobacco-related services received as part of the treatment program (Program Services), and (3) tobacco-related services received from an individual counselor (Clinician services). The Attitude subscale (8 items) includes questions regarding whether clients in the program want to quit smoking, whether the program prioritizes counseling for smoking cessation, and whether the client is aware of community smoking cessation resources. The Program Service scale (8 items) asks whether the current program had provided the client with educational material about quitting smoking, whether quitting smoking is a requirement of the program, and whether the risks of smoking were discussed with the client. Last, the Clinician Service scale (4 items) asks how often, in the past month, the client’s own counselor had encouraged them to quit smoking, to reduce smoking, to use any smoking cessation medications, or arranged a follow up to discuss smoking. All items are scored on a scale from 1-5, and the scale score is the mean of the constituent items. A higher scale score reflects more positive attitudes toward smoking cessation or receipt of more tobacco cessation services from the program or from the counselor. All clients were also asked if “staff and clients ever smoke together” with the response options yes or no (Guydish et al., 2017). As a measure of how well the tobacco policy was communicated to clients, all clients were also asked about the current smoking policy in their program with the response options: “Clients are allowed to smoke in designated smoking area on program property”, “Clients have to leave the program property (across the street or when away to smoke)”, “Clients are not allowed to smoke on or off property” or “I don’t know”.

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

Program directors selected site visit dates, assigned a staff liaison to assemble clients on the site visit day, and provided program census data used to determine client participation rates. Clients could sign up for the study in advance of the site visit, using 30-minute blocks with up to 7 clients per block (limited by the number of iPads available for data collection). Clients who did not sign up in advance could also “walk-in” to any survey period when space was available. Client names on sign-up sheets were used to track which clients had completed the survey, to prevent the same client from taking the survey twice, and as a record of receipt for the post-survey gift cards.

Two research staff were present during each visit. Research staff reviewed information sheets verbally with clients in each group. After reviewing the information sheet, research staff input a unique client ID into each iPad and distributed iPads to participants. Using the iPad, clients again reviewed the study information page, agreed to participate online, and then began the survey. Self-administered surveys were created using Qualtrics™ (Provo, Utah) software. The survey took about 30 minutes to complete. Clients received a $20 gift card for participating in the study. Client surveys were anonymous, and individual clients were not tracked across data collection waves. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco.

2.5. Data Analysis

Cross-sectional and anonymous surveys are expected to represent independent samples. Participants were asked in wave 2 and 3 whether they had taken the survey previously. Individuals indicating that they had previously taken the survey were excluded from the analyses to support independence of the samples.

We first compared demographic variables between the samples at each data collection wave, using Chi-square for categorical variables and the ANOVA for continuous variables. This was to assess any differences in demographic characteristics by survey wave, which may affect differences observed in smoking behavior.

Next, we compared each outcome variable (smoking behaviors and tobacco-related knowledge, attitude and service subscales) between the samples at each data collection wave using omnibus tests (Chi-square and ANOVA procedures) to assess the presence of differences across three waves. This analysis provides an unadjusted assessment of changes in outcome measures between time points and identifies a smaller set of outcome variables for further testing using multivariate models.

Last, for those outcomes where unadjusted comparisons showed significant differences between waves at p < 0.10, we performed regression analyses adjusting for other variables. As recommended by Hosmer and Lemeshow (2000), variables meeting the 0.10 significance level in unadjusted analyses were selected for further evaluation using multivariate models. This approach avoids excluding outcome variables that might be associated with the predictor by being too strict. Regression models were used to compare each outcome (current smoking, cigarettes per day, first cigarette ≤ 30 min after waking, reduced smoking due to program requirements, thinking of quitting in the next 30 days, and staff and clients smoke together) with survey wave as the predictor. One model was run for each outcome variable. To conduct comparisons between waves the model was run twice, first with wave 1 as a reference category and then with wave 2 as a reference category. Regression models adjusted for demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, primary drug for which individuals were in treatment, and length of time in current treatment program) and nesting of clients within program via generalized estimating equation (GEE) models for correlated data. For these regression models, client smoking was analyzed as a dichotomous variable current smoking (yes/no), with never-smokers and former smokers collapsed into one category due to the low prevalence of never smokers in our sample. Logistic regression models were used for dichotomous outcomes (e.g., current smoking) and a Poisson regression model was used for count data (cigarettes per day). Outcome for the Poisson regression was reported using mean ratios, the ratio of the expected outcome between waves. All statistical analyses were done using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Demographic Characteristics Across Waves

As a proportion of all clients living in the treatment programs at the time of data collection, survey participation rates were 95% at wave 1, 91% at wave 2, and 91% at wave 3. A total of 31 clients (18 in wave 2, and 13 in wave 3) indicated they had previously taken the survey and were excluded from the analyses to support independence of the samples. This final sample size used for data waves 1, 2, and 3 were 190, 200, and 201, respectively.

For demographic characteristics reported in Table 1, only length of time in treatment differed significantly across waves (Table 1). Collapsed across waves, the mean age of clients was 41.9 (SD = 11.9), a majority were male (74.8%), and 41.8% had some education beyond high school. One-third (33.2%) were non-Hispanic White, 28.6% were African American, 23.9% were Hispanic/ Latino, and 14.4% were from other racial backgrounds.

Table 1.

Demographics and sample characteristics of SUD treatment clients in across survey waves.

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Pre-TFGa (N=190) |

Wave 2 Post-TFG/ Pre- tax b (N=200) |

Wave 3 Post-Tax c (N=201) |

χ2/F(df) | p-value | |

| Age | 42.5 (12.5) | 41.3 (11.3) | 41.8 (11.9) | 0.5 (2, 588) | 0.617 |

| Sex | 2.2 (4) | 0.705 | |||

| Male | 138 (73.0%) | 156 (78.8%) | 148 (73.6%) | ||

| Female | 48 (25.4%) | 40 (20.2%) | 50 (24.9%) | ||

| Something else | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (1.0%) | 3 (1.5%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 4.3 (6) | 0.630 | |||

| Hispanic/ Latino | 38 (20.0%) | 53 (26.5%) | 50 (24.9%) | ||

| African American | 59 (31.1%) | 49 (24.5%) | 61 (30.3%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 64 (33.7%) | 70 (35.0%) | 62 (30.8%) | ||

| Multiracial/ Other | 29 (15.3%) | 28 (14.0%) | 28 (13.9%) | ||

| Education | 7.5 (4) | 0.113 | |||

| <HS | 47 (24.7%) | 47 (23.5%) | 50 (25.0%) | ||

| HS/GED | 77 (40.5%) | 63 (31.5%) | 59 (29.5%) | ||

| >HS | 66 (34.7%) | 90 (45.0%) | 91 (45.5%) | ||

| Primary drug | 9.4 (6) | 0.151 | |||

| Alcohol | 48 (25.3%) | 50 (25.0%) | 37 (18.5%) | ||

| Stimulants | 85 (44.7%) | 87 (43.5%) | 90 (45.0%) | ||

| Opiates | 45 (23.7%) | 37 (18.5%) | 51 (25.5%) | ||

| Other drug | 12 (6.3%) | 26 (13.0%) | 22 (11.0%) | ||

| Programs | 6.0 (4) | 0.198 | |||

| Site 1 | 39 (20.5%) | 44 (22.0%) | 55 (27.4%) | ||

| Site 2 | 56 (29.5%) | 60 (30.0%) | 68 (33.8%) | ||

| Site 3 | 95 (50.0%) | 96 (48.0%) | 78 (38.8%) | ||

| Length in program (weeks) | 10.1 (9.87) | 8.0 (7.91) | 7.1 (7.12) | 6.6 (2, 586) | 0.001 |

Data collected from three residential drug abuse treatment programs in San Francisco, before and two time after implementation of a tobacco-free grounds (TFG) policy Jan 1st, 2017. Statistical comparisons for each demographic variable between the samples at each data collection wave using Chi-square and ANOVA procedures. Mean (SD) is reported for continuous variables, n (%) is reported for categorical variables. HS = high school; GED = General Education Diploma.

Wave 1 = baseline assessment, prior to implementation of the TFG policy or increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Wave 2 = post implementation of the TFG policy, prior to the increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Wave 3 = post implementation of the TFG policy and post increase in the CA tobacco tax.

3.2. Smoking Behavior Among Clients Pre vs. Post Implementation of A TFG Policy and CA Tobacco Tax Increase

To assess how well the smoking policy was communicated, we asked clients at all three survey waves about their program’s current policy on smoking. A majority of the clients in waves 2 and 3 reported being aware of the TFG policy with 88.8% of clients in wave 1 (pre TFG policy) reporting that “clients were allowed to smoke on program property”, which dropped to 10.5% in wave 2, and 13.1% in wave 3, after the TFG policy was put in place.

Univariate comparisons for tobacco use and program services outcomes, by data collection wave, are shown in Table 2. There were significant differences between waves for prevalence of current smoking status (p =0.008), mean cigarettes smoked per day (p <0.0001), the proportion of people who smoked a cigarette within 30 minutes after waking (p <0.001), and the proportion who reduced smoking due to program requirements (p <0.001).

Table 2.

Tobacco use and program services received across survey waves.

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Pre-TFGa (N=190) |

Wave 2 Post-TFG/ Pre- tax b (N=200) |

Wave 3 Post-Tax c (N=201) |

χ2/F, df | p- value |

|

| Cigarette smoking status | 13.8 (4) | 0.008 | |||

| Current smoker | 155 (81.6%) | 131 (65.5%) | 145 (72.1%) | ||

| Former smoker | 31 (16.3%) | 56 (28.0%) | 45 (22.4%) | ||

| Never smoker | 4 (2.1%) | 13 (6.5%) | 11 (5.5%) | ||

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 11.1 (8.1) | 7.8 (6.3) | 7.3 (5.7) | 13.6 (2,417) | <.0001 |

| First cigarette 30 min after waking | 107 (69.5%) | 58 (45.7%) | 78 (56.5%) | 16.4 (2) | <.001 |

| Past year quit attempt | 99 (57.6%) | 89 (59.3%) | 93 (60.0%) | 0.2 (2) | 0.897 |

| Reduce smoking due to program requirements (% somewhat/ a lot) | 62 (33.5%) | 100 (54.6%) | 90 (48.4%) | 17.5 (2) | <.001 |

| Thinking of quitting in the next 30 days | 63 (40.6%) | 58 (45.7%) | 44 (32.1%) | 5.2 (2) | 0.073 |

| Any lifetime NRT use | 91 (50.0%) | 96 (52.7%) | 82 (44.8%) | 2.4 (2) | 0.305 |

| Any lifetime use of non-NRT tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy | 15 (8.4%) | 18 10.2%) | 13 (7.5%) | 0.8 (2) | 0.658 |

| Tobacco cessation services (S-KAS scale) | |||||

| Attitudes | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.7) | 1.5 (2, 583) | 0.218 |

| Clinician services | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.1) | 0.5 (2, 414) | 0.628 |

| Program services | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.2 (2, 468) | 0.114 |

| Staff and client smoke together | 67 (35.3%) | 48 (24.0%) | 59 (29.8%) | 5.9 (2) | 0.051 |

Data collected from three residential drug abuse treatment programs in San Francisco, before and two times after implementation of a tobacco-free grounds (TFG) policy Jan 1st, 2017. Statistical comparisons for each outcome variable between the samples at each data collection wave using Chi-square and ANOVA procedures. Bold indicates a significant difference, p<0.05 between waves. Mean (SD) is reported for continuous variables, n (%) is reported for categorical variables. NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; S-KAS = smoking knowledge, attitudes and services scale.

Wave 1 = baseline assessment, prior to implementation of the TFG policy or increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Wave 2 = post implementation of the TFG policy, prior to the increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Wave 3 = post implementation of the TFG policy and post increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Regression models were used to examine each outcome variable between waves, adjusting for demographics and controlling for nesting of clients within program (Table 3). Odds of clients being current smokers was lower (AOR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.30, 0.60) in wave 2 (after implementation of TFG) compared to wave 1 (baseline). Adjusted mean ratio (AMR) for cigarettes per day was lower in wave 2 compared to wave 1(AMR = 0.70, CI = 0.59, 0.83). Odds of clients smoking their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking was lower in wave 2 compared to wave 1 (AOR = 0.36, CI = 0.27, 0.47). Odds of clients reporting reducing smoking due to program requirements were higher in wave 2 compared to wave 1 (AOR = 2.54, CI = 1.88, 3.43).

Table 3.

Multivariate regression models of change in tobacco use characteristics across survey waves.

| (Wave 2b vs. Wave 1a (ref))*,† | (Wave 3C vs. Wave 1a (ref))*,† | (Wave 3C vs. Wave 2b (ref))*,† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds/Mean Ratios (95% CI) |

p value1 | Odds/Mean Ratios (95% CI) |

p value1 | Odds/Mean Ratios (95% CI) |

p value1 | |||

| Current smoking | 0.43 (0.30, 0.60) | <0.0001 | 0.51 (0.33, 0.78) | 0.002 | 1.20 (1.11, 1.30) | <0.0001 | ||

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 0.70 (0.59, 0.83) | <0.0001 | 0.67 (0.54, 0.83) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.70, 1.32) | 0.804 | ||

| First cigarette ≤30 min after waking | 0.36 (0.27, 0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.54 (0.25, 1.18) | 0.122 | 1.50 (0.84, 2.69) | 0.173 | ||

| Reduced smoking due to program requirements | 2.54 (1.88, 3.43) | <0.0001 | 1.88 (1.79, 1.99) | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.55 1.00) | 0.048 | ||

| Thinking of quitting in the next 30 days | 1.23 (0.82, 1.85) | 0.319 | 0.65 (0.53, 0.82) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.31, 0.92) | 0.023 | ||

| Staff and client smoke together | 0.56 (0.26, 1.20) | 0.138 | 0.72 (0.32, 1.66) | 0.443 | 1.28 (0.47, 3.47) | 0.624 | ||

Wave 1 = baseline assessment, prior to implementation of the TFG policy or increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Wave 2 = post implementation of the TFG policy, prior to the increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Wave 3 = post implementation of the TFG policy and post increase in the CA tobacco tax.

Adjusted for demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity and education), primary drug, and length of time in treatment; and also controlled for nesting of participants within programs.

Presented are odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes and mean ratios for count outcome. Ref = reference category

Similar results were found when comparing outcome variables between the pre-TFG policy sample (wave 1) and wave 3 (post TFG and post CA tobacco tax increase) with two exceptions. First, odds of clients smoking their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking was no longer significant. Second, odds of participants thinking of quitting in the next 30 days was higher at wave 3 compared to wave 1 (see Table 3).

Odds of clients being current smokers was higher in the post-tax sample (wave 3) compared to the pre-tax sample (wave 2), while odds of reducing smoking due to program requirements were lower. Last, the odds of clients thinking of quitting in the next 30 days were lower in wave 3 compared to wave 2 (see Table 3).

4. Discussion

Implementation of a TFG policy in three residential SUD treatment programs was associated with lower smoking prevalence among clients and, among those who continued to smoke, smoking fewer cigarettes per day and a longer delay between waking and smoking their first cigarette. There was also an increase in the proportion of clients who reported reducing smoking due to program requirements. Prior studies have reported a decrease in client smoking prevalence after the implementation of a TFG policy at residential SUD treatment programs (Guydish et al., 2012; Richey et al., 2017). Taken together, these results suggest that TFG policies may reduce the high prevalence of smoking among individuals in residential SUD treatment.

While all of these studies reported a decrease in client smoking after implementation of the TFG policy, there were differences in the magnitude reported. This is likely due to the specific policy in place at different programs. For example, in the current study, clients were allowed to smoke when off grounds for appointments or other reasons. In discussion with directors, we learned that between waves 2 and 3 (pre vs. post tobacco tax increase) staff began incorporating three smoke breaks both on and off program grounds (one after every meal) throughout the day. This policy change may account for the rebound in smoking prevalence observed between waves 2 and 3. A similar rebound was observed after implementation of TFG policies in residential SUD treatment programs in New York, with client smoking prevalence decreasing from pre- to post-policy (60.7% vs. 52.5%) and then rebounding back to 60.3% (Pagano et al., 2016). The impact of TFG policies between different programs is likely due to how the policy is enacted, enforced, and the availability of tobacco cessation services.

As measured by the Program Service and Clinician Service scales, there was no change in tobacco cessation services, including receipt of NRT or non-NRT smoking cessation pharmacotherapies after implementation of the TFG policy. This differs from prior work that found an increase in tobacco services received by clients after the implementation of a TFG policy (Guydish et al., 2017). However, only 26.2% of SUD treatment programs in the U.S. offered NRT to clients in 2016 (Marynak et al., 2018). Increasing access to tobacco cessation services and access to smoking cessation pharmacotherapies may further promote smoking cessation at these programs as the efficacy of pharmaceutical support for smoking cessation has been found to be higher when combined with a smoke-free policy (Gilpin et al., 2006). However, even without an increase in tobacco cessation services, and as compared to baseline, there was a lower prevalence of current smokers and fewer cigarettes smoked per day by clients at both time points after the implementation of the TFG policy.

The 3rd data collection wave was added to evaluate whether the California state tobacco tax was associated with a further decrease of smoking among clients in SUD treatment. We did not find a decrease in smoking associated with the cigarette tax increase and, instead, found an increase in proportion of clients who smoked cigarettes. This increase may have been due to changes in program policy allowing for greater access for smoking, as described earlier, limiting our ability to observe any impact of the increased tax on smoking behavior. However, as smoking prevalence increased from pre- to post-tax increase, it is reasonable to conclude that the tax increase, combined with the relaxed tobacco use policy, had limited impact on client smoking behavior in this sample. Remler (2004) reports that cigarettes taxes are regressive because low-income smokers end up spending a larger share of their income on cigarettes. However, low income smokers living in states with higher taxes were found to smoke less than low-income smokers living in states with lower taxes (Vijayaraghavan et al., 2013), suggesting that tobacco tax increases can impact smoking behavior among low-income smokers. Our finding regarding the impact of the tobacco-tax increase on client smoking is complicated by staff incorporating three smoke breaks both on and off program grounds between waves 2 and 3 (pre vs. post tobacco tax increase). This policy change may have lessened the impact that the tobacco-tax had on client smoking behavior. Evaluating the impact of tobacco-tax increases among individuals in SUD treatment without changes in program level smoking policies are needed to better understand the impact of these tobacco control policies.

Study limitations include cross-sectional and anonymous survey data collection in each program. While sufficient to measure change in smoking prevalence across data waves, this approach does not permit observation of change in smoking behavior for individual clients. The pre- post study design also lacks a non-TFG comparison condition, which would strengthen attribution of study findings to the TFG policy rather than to other unmeasured factors. One concern raised about TFG policies at SUD treatment programs is that they may result in a decrease in client census. Among the programs examined, there was an increase in the client census at both time periods after implementation compared to the pre-policy survey. This result is similar to what has been reported in one other program after adoption of a TFG policy (Richey et al., 2017). Program directors stated that all three programs were compliant with the TFG policy and a majority of clients in waves 2 and 3 (post TFG policy) reported smoking was not allowed on program property; however, compliance was not directly assessed at the client level. Greater compliance with TFG policy adoption is another factor that may contribute to effectiveness of TFG policy adoption and should be monitored in future studies. Research is needed to determine the impact of TFG and tobacco tax increase on clients smoking after leaving residential SUD treatment to determine if these policies result lasting impacts on smoking behaviors among a population with a high rate of tobacco use.

4.1. Conclusion

Smoking prevalence and cigarettes smoked per day were lower among residential clients in SUD treatment after implementation of a TFG policy, as compared to clients surveyed before the policy implementation. This suggests that TFG policies may be effective in promoting smoking cessation among clients in SUD treatment settings. Federal and state agencies that fund drug abuse treatment, and state authorities that license and regulate treatment programs, should promote tobacco free policies. Programs implementing TFG policies should increase tobacco cessation services, including providing NRT to clients.

Highlights.

Tobacco use disproportionately affects individuals in addiction treatment.

Examined impact of a tobacco-free grounds (TFG) policy on client smoking.

Implementation of a TFG policy was associated with reductions in client smoking.

Increased cigarette tax was not associated with further reductions in client smoking.

TFG policies should be promoted in addiction treatment programs.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the California Tobacco Related-Disease Research Program (TRDRP 25CP-0002) and the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA082103. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the NIH fellowship grant F32 DA 042554. These funding sources had no role in the analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Apollonio DE, Malone RE, 2005. Marketing to the marginalised: tobacco industry targeting of the homeless and mentally ill. Tob. Control 14, 409–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader P, Boisclair D, Ferrence R, 2011. Effects of tobacco taxation and pricing on smoking behavior in high risk populations: a knowledge synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 4118–4139. 10.3390/ijerph8114118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim S-Y, Colby S, Conti D, Giovino GA, Hatsukami D, Hyland A, Krishnan-Sarin S, Niaura R, Perkins KA, Toll BA, 2007. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res 9, S555–S570. 10.1080/14622200701673480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera FC, Anteneh B, Le T, Delucchi K, Guydish J, 2015. Tobacco-related mortality among persons with mental health and substance abuse problems. Plos One 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Johnson CG, England LJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM, 2014. Tobacco industry marketing to low socioeconomic status women in the U.S.A. Tob. Control 23, e139–146. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Gatley JM, Sykes J, Taylor L, 2018. The prominence of smoking-related mortality among individuals with alcohol- or drug-use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 37, 97–105. 10.1111/dar.12475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Breslau N, Hatsukami D, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Grucza RA, Salyer P, Hartz SM, Bierut LJ, 2014. Smoking cessation is associated with lower rates of mood/anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Psychol. Med 44,2523–2535. 10.1017/S0033291713003206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT, 2012. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob. Control 21, 172–180. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Haug NA, Guydish JR, Sorensen JL, Delucchi K, 2009. Cigarette smoking among opioid-dependent clients in a therapeutic community. Am. J. Addict 18, 316–320. http://dx.doi.org/911211794[pii]10.1080/10550490902925490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn A, Elmasry H, Niaura R, 2017. Facility-level, state, and financial factors associated with changes in the provision of smoking cessation services in US substance abuse treatment facilities: Results from the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services 2006 to 2012. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 77, 107–114. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton W, 2018. The need to incorporate smoking cessation into behavioral health treatment. Am. J. Addict 27, 42–43. 10.1111/ajad.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Fernández V, Wilson WT, Shedrick DA, Kyburz B, Samaha HL, Stacey T, Williams T, Lam CY, Reitzel LR, 2017. Implementation of a tobacco-free workplace program at a local mental health authority. Transl. Behav. Med 7 10.1007/s13142-017-0476-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon A, Preston SH, 2012. Estimating smoking-attributable mortality in the United States. Demography 49, 797–818. 10.1007/s13524-012-0108-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron JC, Brunette MF, He X, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Drake RE, 2011. Course of smoking and quit attempts among clients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Psychiatr. Serv 62, 353–359. 10.1176/ps.62.4.pss6204_0353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Chan M, Delucchi KL, Ziedonis D, 2011. Measuring smoking knowledge, attitudes and services (S-KAS) among clients in addiction treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 114, 237–241. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Kulaga A, Zavala R, Brown LS, Bostrom A, Ziedonis D, Chan M, 2012. The New York policy on smoking in addiction treatment: findings after 1 year. Am. J. Public Health 102, e17–25. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Pramod S, Le T, Gubner NR, Campbell B, Roman P, 2016b. Use of multiple tobacco products in a national sample of persons enrolled in addiction treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 166, 93–99. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EJ, Fallin A, Darville A, Kercsmar SE, McCann M, Record RA, 2012. The three Ts of adopting tobacco-free policies on college campuses. Nurs. Clin. North Am 47, 109–117. 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Andersen-Rodgers E, Zhang X, Roeseler A, Sun DL, Johnson TO, Schleicher NC, 2017. Neighborhood variation in the price of cheap tobacco products in California: results from healthy stores for a healthy community. Nicotine Tob. Res 19, 1330–1337. 10.1093/ntr/ntx089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM, Melton LJ 3rd, 1996. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA 275, 1097–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Preventing Nicotine Addiction in Children and Youths, 1994. Lynch BS, Bonnie RJ, (Eds.), Growing up tobacco free: Preventing Nicotine Addiction in Children and Youths. National Academies Press (US), Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, Homa DM, Babb SD, King BA, Neff LJ, 2018. Current cigarette smoking among adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 67, 53–59. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn CS, Tsoh JY, Weisner CM, 2003. Changes in smoking status among substance abusers: baseline characteristics and abstinence from alcohol and drugs at 12-month follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend. 69, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH, 2000. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA 284, 2606–2610. 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewit EM, Coate D, 1982. The potential for using excise taxes to reduce smoking. J. Health Econ 1, 121–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marynak K, VanFrank B, Tetlow S, Mahoney M, Phillips E, Jamal Mbbs A, Schecter A, Tipperman D, Babb S, 2018. Tobacco cessation interventions and smoke-free policies in mental health and substance abuse treatment facilities - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 67, 519–523. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6718a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, Acquavita SP, Dunn KE, Stoller KB, Stitzer ML, 2014. Characterizing smoking, cessation services, and quit interest across outpatient substance abuse treatment modalities. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 46, 194–201. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey K, Thrul J, Ramo D, 2017. Impact of quitting smoking and smoking cessation treatment on substance use outcomes: An updated and narrative review. Addict. Behav 65, 161–170. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton ET, Morice AH, 2000. Breath carbon monoxide as an indication of smoking habit. CHEST 117, 758–763. https://doi.Org/10.1378/chest.117.3.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muilenburg JL, Laschober TC, Eby LT, Moore ND, 2016. Prevalence of and factors related to tobacco ban implementation in substance use disorder treatment programs. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 43, 241–249. 10.1007/s10488-015-0636-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. The health consequences of smoking-50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Atlanta, GA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano A, Guydish J, Le T, Tajima B, Passalacqua E, Soto-Nevarez A, Brown LS, Delucchi KL, 2016. Smoking behaviors and attitudes among clients and staff at New York addiction treatment programs following a smoking ban: findings after 5 years. Nicotine Tob. Res 18, 1274–1281. 10.1093/ntr/ntv116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remler DK, 2004. Poor smokers, poor quitters, and cigarette tax regressivity. Am. J. Public Health 94, 225–229. Doi 10.2105/Ajph.94.2.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richey R, Garver-Apgar C, Martin L, Morris C, Morris C, 2017. Tobacco-free policy outcomes for an inpatient substance abuse treatment center. Health Promot. Pract 18, 554–560. 10.1177/1524839916687542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Ahluwalia HK, Mosier MC, Nazir N, Ahluwalia JS, 2002. A population-based study of cigarette smoking among illicit drug users in the United States. Addiction 97, 861–869. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel SE, Metzger K, Guerra A, Patton-Levine J, Singh S, Wilson WT, Huang P, 2017. Effects of a Tobacco-Free Work Site Policy on Employee Tobacco Attitudes and Behaviors, Travis County, Texas, 2010-2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 14, E133 10.5888/pcd14.170059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Cummins SEC, 2015. Smoking cessation services and smoke-free policies at substance abuse treatment facilities: national survey results. Psychiatr. Serv 66, 610–616. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton E, Tzelepis F, Shakeshaft A, Guillaumier A, McCrabb S, Bonevski B, 2018. Integrating smoking cessation care in alcohol and other drug treatment settings using an organizational change intervention: a systematic review. Addiction 113, 2158–2172. 10.1111/add.14369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Caviness CM, Kurth ME, Audet D, Olson J, Anderson BJ, 2013. Varenicline for smoking cessation among methadone-maintained smokers: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 133, 486–493. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2017. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2015. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. BHSIS Series Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. BHSIS Series S-88, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 17-5031, Rockville, MD: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2015_National_Survey_of_Substance_Abuse_Treatment_Services.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration., 2013. The NSDUH Report, Data Spotlight: Adults with mental illness or substance use disorder account for 40 Percent of all cigarettes smoked. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/spot104-cigarettes-mental-illness-substance-use-disorder/spot104-cigarettes-mental-illness-substance-use-disorder.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Thurgood SL, McNeill A, Clark-Carter D, Brose LS, 2016. A systematic review of smoking cessation interventions for adults in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Nicotine Tob. Res 18, 993–1001. 10.1093/ntr/ntv127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE, 1984. Cigarette taxation: doing good by doing well. J. Public Health Policy 5, 312–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Platt J, Esan H, Galea S, Erlich D, Goodwin RD, 2017. Cigarette smoking is associated with increased risk of substance use disorder relapse: a nationally representative, prospective longitudinal investigation. J. Clin. Psychiatry 78, e152–e160. 10.4088/JCP.15m10062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW and Lemeshow S, Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin EA, Messer K and Pierce JP, Population effectiveness of pharmaceutical aids for smoking cessation: what is associated with increased success?, Nicotine Tob. Res 8, 2006, 661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Le T, Campbell B, Yip D, Ji S and Delucchi K, Drug abuse staff and clients smoking together: A shared addiction, J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 76, 2017, 64–68, 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan M, Messer K, White MM and Pierce JP, The effectiveness of cigarette price and smoke-free homes on low-income smokers in the United States, Am. J. Public Health 103, 2013, 2276–2283, 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]