Abstract

Objectives:

Pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) is a rare condition that has been linked to prematurity and congenital heart disease (CHD). Despite these associations, treatment options are limited and outcomes are guarded. We investigated differences in PVS outcomes based on the presence of CHD and prematurity, and risk factors for mortality or lung transplantation in PVS.

Methods:

Single center retrospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with PVS between January 2005 and May 2016, identified by ICD codes with chart validation. Cox proportional hazard models assessed risk factors for the composite outcome of mortality or lung transplantation.

Results:

Ninety-three patients with PVS were identified: 65 (70%) had significant CHD, 32 (34%) were premature, and 14 (15%) were premature with CHD. Sixty-five (70%) underwent a PVS intervention and 42 (46%) underwent ≥2 interventions. Twenty-five (27%) subjects died or underwent lung transplant 5.8 months (Interquartile range (IQR) 1.1, 15.3) after diagnosis. There was no difference in age at diagnosis or mortality based on presence of CHD or prematurity. PVS diagnosis before age 6 months and greater than one pulmonary vein affected at diagnosis were associated with higher mortality (HR 3.4 (95% CI 1.5, 7.5), p=0.003, and HR 2.1 per additional vein affected (95% CI 1.3, 3.4), p=0.004, respectively).

Conclusions:

Survival in children with PVS is poor, independent of underlying CHD or prematurity. Younger age and greater number of veins affected at diagnosis are risk factors for worse outcome. Understanding causal mechanisms and development of treatment strategies are necessary to improve outcomes.

Background

Pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) is a rare entity, with a previously estimated prevalence of 0.03% in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD).1,2 While PVS can be present after intervention for primary pulmonary vein anomalies,3 such as total and partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, in recent years there have been numerous reports of isolated PVS in patients with structurally normal hearts.4–8 In addition, PVS has been described in association with prematurity, particularly in patients with severe chronic lung disease.4,8,11 In this population, PVS is usually detected later in infancy, suggesting a component of postnatal factors to disease development or progression.6,8,11 Outcomes in PVS are poor due to development of pulmonary hypertension, and surgical or catheter based interventions have demonstrated limited success due to restenosis, progression of disease, and ultimately death.2,6,8,10–21 We sought to investigate 1) the association of CHD and prematurity with mortality or lung transplantation in subjects with PVS, and 2) additional risk factors for mortality or lung transplantation in subjects with PVS. We hypothesized that CHD and prematurity would confer increased risk for mortality in this disease, and that a higher number of veins affected would result in worse outcomes.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with confirmed diagnosis of PVS followed at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia between January 2005 and May 2016. Subjects were first identified by database inquiry for ICD-9 codes 747.4 (anomalies of pulmonary veins) or 747.49 (stenosis of pulmonary veins). Diagnosis of PVS was confirmed by manual review of charts, including echocardiographic, catheterization, and MRI/CT reports, as available. Subjects met inclusion criteria if they were under 18 years of age and there was at least one vein with either: 1) a gradient of 5mmHg or more by cardiac catheterization or echocardiography; 2) presence of pulmonary vein atresia on angiography, or 3) appearance of discrete stenosis on angiography not due to external compression.

The primary exposures of interest were the presence of CHD and the presence of prematurity. CHD was defined as complex lesions or lesions requiring surgical intervention or palliation. Patent ductus arteriosus, or atrial or small ventricular septal defects that did not require surgical or catheter-based intervention to correct were excluded from this group. Prematurity was defined as gestational age <37 weeks. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Data collection

Covariates of interest included demographics, gestational age, birth weight, birth length, presence of genetic disorders, age at PVS diagnosis, presence of pulmonary hypertension (defined as mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥25mmHg by cardiac catheterization, or presence of echocardiographic markers of elevated right ventricular pressure, including septal flattening/bowing or greater than half-systemic right ventricular pressure estimate by tricuspid regurgitant jet), number of pulmonary veins affected at diagnosis and at last follow-up, type and number of interventions, and time between diagnosis and intervention. The primary outcome was the composite outcome of death or lung transplantation. CHD-specific data included type of CHD, type of surgical repair, age at CHD surgical repair, and the presence of a primary pulmonary vein anomaly, defined as total or partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, including Scimitar syndrome. CHD was further divided into non-complex (isolated ASD or VSD) and complex CHD. Premature-specific data included degree of prematurity (defined as premature (32 to <37 weeks gestational age), very premature (28–31 weeks gestational age), and extremely premature (<28 weeks gestational age)), diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia/chronic lung disease, need for intubation during neonatal admission, presence of necrotizing enterocolitis or sepsis prior to PVS diagnosis, tracheostomy, use of systemic steroids during neonatal hospitalization, and use of oxygen on hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards models were run to determine risk factors for the composite outcome of mortality or lung transplantation in subjects with PVS. Time to event was defined as time from date of PVS diagnosis until death or lung transplant, with censoring at date of last follow-up for survivors or five years following diagnosis, whichever was earlier. Five years was chosen due to the rarity of events beyond this period. The survival probabilities were plotted against discrete covariates using Kaplan-Meier curves. For the primary analysis of risk factors for our combined mortality/transplant outcome, we used univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. Risk factors of interest include the presence of CHD or prematurity, age <6 months at diagnosis, number of pulmonary veins involved and presence of bilateral disease, need for intervention, and presence of pulmonary hypertension. Risk factors considered for inclusion in the multivariable model were found to be associated with outcome in separate univariable models (p<0.2), were not collinear with other covariates in the model, and were limited to 1–2 variables due to the small sample size. Interactions between the presence of CHD and prematurity were assessed and included in the model, if significant. Verification of the proportional hazards assumption was performed for each risk factor by plotting the Schoenfeld residuals against time. Kaplan-Meier log-rank test was used to test the effect of intervention on mortality among subjects undergoing an intervention for PVS. Risk factors analyzed included type of primary intervention and number of procedures performed.

Descriptive statistics are presented as frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation or median (Interquartile range (IQR)) for continuous variables. Categorical variables are compared using Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or KruskalWallis test by ranks according to distribution. The two-sided statistical significance level was set at 0.05. All data analysis was performed using STATA 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study cohort

Ninety-three subjects were included in this study. Sixty-five subjects (70%) had significant CHD and 32 (34%) were premature. Fourteen (15%) had CHD and were premature. There were no significant differences in gender, race, ethnicity, age of diagnosis, or presence of genetic syndromes based on the presence of CHD or prematurity (Table 1). Pulmonary hypertension was more common among subjects without CHD (p=0.04) and among premature subjects (p=0.003).

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics

| Over all(n=93) | CHD(n=65) | No CHD(n=28) | p-value | Prematurity(n=32) | No prematurity(n=61) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 56 (60%) | 53 (66%) | 13 (46%) | 0.1 | 15 (47%) | 41 (67%) | 0.08 |

| Ethnicity Non-Hispanic | 71 (76%) | 51 (78%) | 20 (71%) | 0.1 | 28 (88%) | 43 (70%) | 0.3 |

| Hispanic | 11 (12%) | 9 (14%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (6%) | 9 (15%) | ||

| Not answered | 11 (12%) | 5 (8%) | 6 (22%) | 2 (6%) | 9 (15%) | ||

| Race African American | 2 (23%) | 13 (20%) | 8 (29%) | 0.4 | 12 (37%) | 9 (15%) | 0.1 |

| Caucasian | 48 (52%) | 37 (57%) | 11 (39%) | 15 (47%) | 33 (54%) | ||

| Asian | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | ||

| Other | 22 (24%) | 14 (21%) | 9 (32%) | 5 (16%) | 18 (29%) | ||

| Genetic syndrome | 18 (20%) | 14 (23%) | 4 (15%) | 0.5 | 7 (23%) | 11 (19%) | 0.9 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 51 (57%) | 30 (49%) | 21 (75%) | 0.04 | 24 (80%) | 27 (46%) | 0.003 |

| Age at diagnosis, months | 7.2 (3.7, 26.4) | 6.9 (5.3, 11.0) | 8.0 (3.3, 31.7) | 0.6 | 7.7 (5.2, 14.0) | 7.1 (3.3, 45.1) | 1 |

CHD characteristics are listed in Table 2. Sixty (92%) subjects underwent surgical repair. Thirty-one (36%) subjects had a congenital pulmonary vein anomaly, and 18 (19%) had both a primary pulmonary vein anomaly and another form of CHD (Table 2).

Table 2:

CHD and Premature patient characteristics

| CHD CHARACTERISTICS (N=65) | |

|---|---|

| Type of CHD | |

| Ventricular septal defect | 10 (15%) |

| Atrioventricular Canal | 6 (9%) |

| Hypoplastic Center Heart Syndrome | 10 (15%) |

| Heterotaxy | 12 (18%) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot/Double outlet right ventricle | 5 (8%) |

| Other single ventricle | 8 (12%) |

| Other two ventricle | 1 (2%) |

| Complex CHD | 60 (92%) |

| Congenital pulmonary vein anomaly | |

| None | 34 (52%) |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous return | 21 (32%) |

| Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return | 9 (14%) |

| Scimitar syndrome | 1 (2%) |

| Age at CHD repair (months) | 2.2 (0.1, 7.2) |

| PREMATURE CHARACTERISTICS (N=32) | |

| Premature gestational age (weeks) | 30.6 ± 5.1 |

| Degree of prematurity | |

| 32–37 weeks | 16 (50%) |

| 28–31 weeks | 4 (13%) |

| <28 weeks | 12 (37%) |

| Premature birth weight (kg) | 1.5 ± 0.9 |

| Chronic lung disease | 19 (60%) |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis or sepsis | 20 (63%) |

| Large PDA prior to diagnosis | 19 (59%) |

| Use of systemic steroids | 8 (25%) |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 9 (28%) |

| Intubation | 22 (69%) |

| Discharged on oxygen | 18 (56%) |

| Tracheostomy | 13 (41%) |

Premature subjects were born at a gestational age of 30.6 ± 5.1 weeks and weight of 1.5 ± 0.9 kg. Inflammatory conditions, such as necrotizing enterocolitis or sepsis, and intubation during initial hospitalization were prevalent within the premature population (Table 2).

Baseline characteristics

The number of pulmonary veins affected at diagnosis and presence of bilateral disease were similar between groups (Table 3). Interventions were performed in the majority of subjects (70%), with comparable prevalence of intervention between groups. Non-CHD subjects were more likely to undergo balloon angioplasty as the primary intervention for PVS, whereas CHD subjects were more likely to undergo surgical intervention. Premature subjects were more likely to undergo balloon angioplasty, whereas non-premature subjects were more likely to undergo surgical intervention. The re-intervention rate was high but there was no difference based on the presence of CHD or prematurity.

Table 3:

Pulmonary vein characteristics and outcome

| Over all (n=93) | CHD (n=65) | No CHD (n=28) | p-value | Premat urity (n=32) | No premat urity (n=61) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of pulmonary veins affected | 2 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.8 | 2 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 2) | 0.7 |

| Bilateral disease | 27 (29%) | 17 (26%) | 10 (35%) | 0.5 | 11 (34%) | 16 (26%) | 0.5 |

| Type of primary intervention None Surgery Balloon angioplasty Stent | 28 (30%) 28 (30%) 32 (34%) 5 (6%) | 19 (29%) 25 (38%) 18 (28%) 3 (5%) | 9 (32%) 3 (11%) 14 (50%) 2 (7%) | 0.03 | 9 (28%) 4 (13%) 17 (53%) 2 (6%) | 19 (31%) 2 (39%) 3 (25%) 3 (5%) | 0.01 |

| Number of interventions None 1 2 or more | 28 (30%) 23 (25%) 42 (45%) | 19 (29%) 17 (26%) 29 (45%) | 9 (32%) 6 (21%) 13 (47%) | 0.9 | 9 (28%) 7 (22%) 16 (50%) | 19 (31%) 16 (26%) 26 (43%) | 0.9 |

| Lung transplant | 4 (4%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (4%) | 1 | 2 (6%) | 2 (3%) | 0.6 |

| Death | 23 (25%) | 18 (28%) | 8 (29%) | 1 | 8 (25%) | 18 (30%) | 0.8 |

| Median time to transplant/death (months) | 5.8 (1.1, 15.3) | 15.3 (3.8, 54.7) | 3.8 (0.8, 9.3) | 0.053 | 10.1 (5.8, 18.8) | 4.7 (1.6, 17.3) | 0.6 |

There were a total of 23 deaths (25%) and four lung transplants (4%) in the study population, at a median interval of 5.8 months (IQR 1.1, 15.3) from PVS diagnosis, with overall transplant-free survival of 73%. Two deaths occurred in subjects who had previously received a lung transplant. One, three, and five-year transplant-free survival was 81%, 71%, and 67%, respectively. There was a trend towards longer median time to death or transplant among those with CHD as compared to those without CHD (15.3 months (IQR 3.8, 54.7) vs 3.8 months (IQR 0.8, 9.3), respectively, p=0.053). There was no difference in time to death or transplant based on the presence of prematurity (p=0.6).

Risk factors for mortality

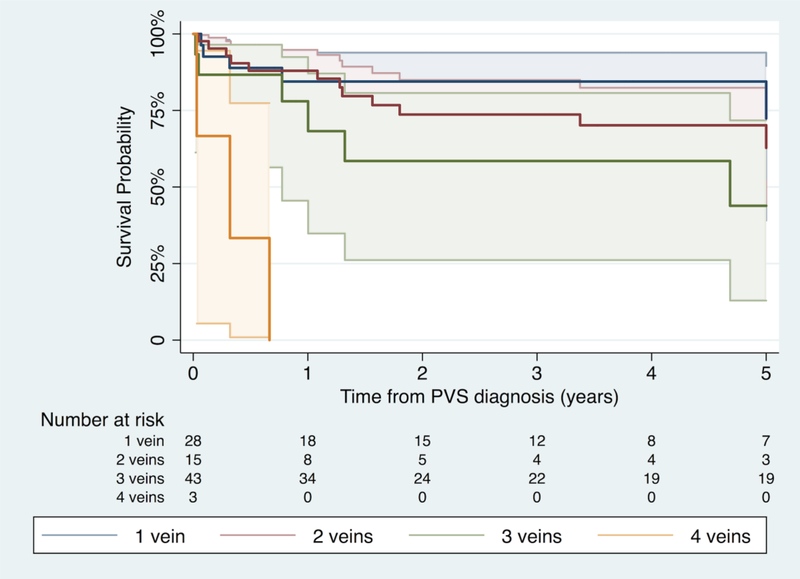

The univariable Cox proportional hazards model identified the following variables that were significantly associated with mortality: greater number of pulmonary veins affected at diagnosis, presence of bilateral disease, pulmonary hypertension, presence of a genetic syndrome, and age <6 months at diagnosis. Presence of CHD or prematurity was not significant. Due to collinearity between number of pulmonary veins affected and presence of bilateral disease, only number of pulmonary veins affected was included in the multivariable analysis. The multivariable Cox proportional hazards model retained two of these predictors and provided adjusted hazard ratios for these risk factors. Age <6 months and number of veins were each associated with a more than 2-fold greater hazard of mortality after adjusting for the effect of the other variable (Table 4, Figures 1, 2).

Table 4:

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of transplant-free survival.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Age at diagnosis <6 months | 3.1 | 1.4, 7.9 | 0.005 | 3.4 | 1.5, 7.5 | 0.003 |

| CHD | 0.6 | 0.3, 1.4 | 0.2 | |||

| Bilateral disease | 2.5 | 1.2, 5.4 | 0.016 | |||

| Number of pulmonary veins at diagnosis | 2.4 | 1.4, 4.1 | 0.001 | 2.1 | 1.3,3.4 | 0.004 |

| Need for Intervention | 0.7 | 0.3, 1.7 | 0.45 | |||

| Genetic syndrome | 2.4 | 1.03, 5.7 | 0.04 | |||

| Presence of pulmonary hypertension | 2.5 | 1.0, 6.3 | 0.05 | |||

| Presence of prematurity | 1.1 | 0.5, 2.5 | 0.7 | |||

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier survival curve stratified by number of pulmonary veins involved at diagnosis.

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier survival curve stratified by age at diagnosis.

For patients who underwent pulmonary vein interventions, there was no difference in overall survival based on type of intervention (catheterization vs. surgery) (p=0.28). However, subjects who underwent two or more procedures had higher mortality than those who only underwent one procedure (Figure 3, p=0.004).

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier survival curve stratified by number of PVS interventions among subjects requiring intervention.

We did not identify significant risk factors for mortality that were specific to subjects with CHD, including type of congenital heart disease, single vs. two-ventricle physiology, presence of complex CHD, or presence/type of congenital pulmonary vein anomaly. Likewise, we did not identify premature-group specific factors associated with mortality, such as gestational age, birth weight, chronic lung disease, necrotizing enterocolitis or sepsis, tracheostomy, and presence of a large patent ductus arteriosus. There was no difference in survival (p=0.6) or age of diagnosis (p=0.2) based on the degree of prematurity.

Discussion

Outcomes for patients with PVS are generally poor. In this study, we report risk factors for mortality in a large group of patients with PVS. We found significant mortality within one year of diagnosis, independent of underlying diagnosis of CHD and/or prematurity. History of prematurity or CHD is not independently associated with poor survival. Younger age at PVS diagnosis and greater number of pulmonary veins involved were identified as independent risk factors for death or lung transplantation. We report an overall transplant-free survival of 73%, which is similar to recent studies of PVS among premature infants and patients with congenital PVS.22–24 While this survival rate is low for a pediatric population, it appears better than prior PVS reports documenting survival rates in the range of 40–50%.2,8,9,21 These differences in survival could be ascribed to differences in populations being studied. While prior reports focused on subjects with prematurity or children undergoing intervention for PVS, therefore likely representing a sicker cohort, we included subjects in whom only one vessel was involved, which in isolation, had been demonstrated to be less likely to progress, or to be associated with death.2,13 We therefore possibly report on a cohort with less severe disease, and thus lower mortality as compared to other studies.

Interestingly, neither CHD nor prematurity were risk factors for mortality, and there was no significant difference in time from diagnosis to mortality between groups. As our study is observational, we cannot ascribe the degree to which PVS contributed directly to mortality; however, considering a much higher mortality than the CHD or premature population at large, and the lack of difference in mortality based on the presence of CHD or prematurity, we can infer that PVS likely contributes to mortality, especially among subjects with more significant pulmonary venous disease.25–27 The short time between diagnosis and death in our study underscores the unremitting nature of this disease, similarly to other reports.8,21

Furthermore, there was no significant differences in most baseline characteristics between subjects with or without prematurity or CHD. Premature subjects had a higher incidence of pulmonary hypertension; however, considering the known association between chronic lung disease and pulmonary hypertension in this population, this finding is not surprising.28 The lack of differences in most baseline characteristics would suggest that the development of PVS is a process independent of underlying prematurity or CHD. Additional studies are necessary to elucidate potential underlying developmental or genetic factors that may result in increased risk for PVS.

One of the goals of this study was to identify risk factors for PVS in patients with prematurity, given the clinical observation of increased prevalence of PVS in this population in recent years. We report on a population that is seemingly comparable to other studies in terms of baseline characteristics, degree of prematurity, birth weight, chronic lung disease and inflammatory conditions, such as necrotizing enterocolitis and sepsis.6,8,9,13,29 However, despite the prevalence of very and extreme prematurity, chronic lung disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, or sepsis in our population, these factors were not associated with mortality.

Patients with PVS diagnosed before 6 months of age had nearly a three-fold increase in mortality. This is similar to recent reports which demonstrated a significant survival benefit with older age at diagnosis.12,22 Considering that this association was independent of number of veins affected at diagnosis, our findings would support the conclusion that PVS at a young age carries an especially poor prognosis. These findings would suggest that screening for PVS may be beneficial during routine follow-up for infants with CHD and in the premature population under six months of age, as earlier detection would allow earlier and more aggressive intervention and closer follow-up, which could potentially modify outcomes. Pathologic mechanisms underlying this phenomenon were beyond the scope of this study, and therefore further research into this area is needed.

We found that type of initial intervention was not associated with outcome in our population. However, subjects requiring two or more interventions had higher mortality, suggesting that those requiring more procedures likely represent a sicker subset with persistent or recurrent PVS. In contrast to our result, a recent study reported improved survival was identified among subjects undergoing reintervention.30 These discrepant results may be a function of the cohort examined. The subjects in their study were younger, more likely to receive drug-eluting stents, and tended to die earlier, potentially resulting in a cohort of survivors that underwent numerous interventions and perhaps had less severe disease.

Limitations

There were limitations to this study. This was a single center retrospective analysis, and therefore there was potential for incomplete ascertainment, either due to improper coding or incomplete evaluation on echocardiograms, resulting in potential selection bias of a sicker population. Management strategies at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia are not protocolized; therefore, decision to intervene, and type of intervention, were individualized based on the patient and care team. The retrospective nature of this study could lead to missing data, especially if diagnosis was significantly delayed. While we presume PVS contributed to mortality, we report associations, and therefore, it is plausible that death was due to other causes rather than PVS itself. Due to the rarity of this disease, our sample size was limited and included a heterogeneous population, thus limiting our ability to completely ascertain risk factors for mortality and to adjust for additional potential confounders. Finally, this was a single center study, and therefore the results may not be generalizable to all centers due to variability in management strategy and outcomes.

Conclusions

PVS is associated with poor outcomes independently of CHD, prematurity, or treatment strategy. Early age and greater than one pulmonary vein affected at diagnosis stratify patients towards a greater risk and should be considered in patient counseling and follow up. Further study is needed to evaluate causal mechanisms of PVS in CHD and premature infants, with the long-term goal of developing treatment strategies that could lead to improved survival.

CENTRAL FIGURE LEGEND

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for subjects with PVS stratified by age at diagnosis.

VIDEO LEGEND

An AP projection of a right pulmonary artery angiogram in a 5 month old ex-32 week infant with history of chronic lung disease and severe right sided pulmonary vein stenosis with prior history of right lower pulmonary vein stenting. Angiogram demonstrates significant in-stent re-stenosis and delayed venous return into the left atrium.

Supplementary Material

Central Message

PVS outcomes are poor, especially among young children, regardless of underlying disease or intervention. Younger diagnosis age and greater number of veins affected are risk factors for mortality.

Perspective Statement

PVS is associated with significant mortality, regardless of the presence of prematurity or CHD, and despite various potential treatment strategies. Routine surveillance and evaluation for PVS should be considered, especially among premature population with chronic lung disease. Understanding causal mechanisms and development of effective treatment strategies are necessary to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [NIH grants T32 HL007915 (MPD), K01HL125521 (LMR)], and Pulmonary Hypertension Association supplement to K01HL125521 (LMR).

Abbreviations

- PVS

(Pulmonary Vein Stenosis)

- CHD

(Congenital Heart Disease)

- IQR

(Interquartile Range)

- CT

(Computed tomography)

- MRI

(Magnetic resonance imaging)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia IRB: #16–013070, Approved 9/8/16

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Breinholt JP, Hawkins JA, Minich L, Tani LY, Orsmond GS, Ritter S, et al. Pulmonary vein stenosis with normal connection: associated cardiac abnormalities and variable outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt DB, Moller JH, Larson S, Johnson MC. Primary Pulmonary Vein Stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:568–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalfa D, Belli E, Bacha E, Lambert V, di Carlo D, Kostolny M, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors for postsurgical pulmonary vein stenosis in the current era. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin JT, Hamm CR, Zayek M, Eyal FG, Carlson S, Manci E. Acquired LeftSided Pulmonary Vein Stenosis in an Extremely Premature Infant: A New Entity? J Pediatr. 2009;154:459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakrabarti S, Mittal R, Gnanapragasam JP, Martin RP. Acquired stenosis of normally connected pulmonary veins. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaillard SM, Godart FR, Rakza T, Chanez A, Lequien P, Wurtz AJ, et al. Acquired pulmonary vein stenosis as a cause of life-threatening pulmonary hypertension. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:275–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SC, Rabah R. Pulmonary Venous Stenosis in a Premature Infant with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Clinical and Autopsy Findings of these Newly Associated Entities. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012;15:160–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossner DM, Kim DW, Maher KO, Mahle WT. Pulmonary Vein Stenosis: Prematurity and Associated Conditions. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e656–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seale AN, Webber SA, Uemura H, Partridge J, Roughton M, Ho SY, et al. Pulmonary vein stenosis: the UK, Ireland and Sweden collaborative study. Heart. 2009;95:1944–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holcomb RG, Tyson RW, Ivy DD, Abman SH, Kinsella JP. Congenital pulmonary venous stenosis presenting as persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;28:301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balasubramanian S, Marshall AC, Gauvreau K, Peng LF, Nugent AW, Lock JE, et al. Outcomes After Stent Implantation for the Treatment of Congenital and Postoperative Pulmonary Vein Stenosis in Children. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinonez LG, Gauvreau K, Borisuk M, Ireland C, Marshall AM, Mayer JE, et al. Outcomes of surgery for young children with multivessel pulmonary vein stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:911–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swier N, Richards B, Cua C, Lynch S, Yin H, Nelin L, et al. Pulmonary Vein Stenosis in Neonates with Severe Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanagawa B, Alghamdi AA, Dragulescu A, Viola N, Al-Radi OO, Mertens LL, et al. Primary sutureless repair for ―simple‖ total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: Midterm results in a single institution. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1346–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Driscoll DJ, Hesslein PS, Mullins CE. Congenital stenosis of individual pulmonary veins: clinical spectrum and unsuccessful treatment by transvenous balloon dilation. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:1767–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devaney EJ, Ohye RG, Bove EL. Pulmonary Vein Stenosis Following Repair of Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2006;9(1):51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Najm HK, Caldarone CA, Smallhorn J, Coles JG. A sutureless technique for the relief of pulmonary vein stenosis with the use of in situ pericardium. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:468–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanter KR, Kirshbom PM, Kogon BE. Surgical Repair of Pulmonary Venous Stenosis: A Word of Caution. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:1687–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo Rito M, Gazzaz T, Wilder T, Saedi A, Chetan D, Van Arsdell GS, et al. Repair Type Influences Mode of Pulmonary Vein Stenosis in Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Drainage. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:654–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi G, Zhu Z, Chen H, Zhang H, Zheng J, Liu J. Surgical repair for primary pulmonary vein stenosis: Single-institution, midterm follow-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015; 150: 181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song MK, Bae EJ, Jeong SI, Kang IS, Kim NK, Choi JY, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Prognostic Factors of Primary Pulmonary Vein Stenosis or Atresia in Children. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahgoub L, Kaddoura T, Kameny AR, Lopez Ortego P, Vanderlaan RD, Kakadekar A, et al. Pulmonary vein stenosis of ex-premature infants with pulmonary hypertension and bronchopulmonary dysplasia, epidemiology, and survival from a multicenter cohort. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalfa D, Belli E, Bacha E, Lambert V, di Carlo D, Kostolny M, et al. Primary Pulmonary Vein Stenosis: Outcomes, Risk Factors, and Severity Score in a Multicentric Study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo Rito M, Gazzaz T, Wilder TJ, Vanderlaan RD, Van Arsdell GS, Honjo S, et al. Pulmonary vein stenosis: Severity and location predict survival after surgical repair. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:657–666.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger JT, Holubkov R, Reeder R, Wessel DL, Meert K, Berg RA, et al. Morbidity and mortality prediction in pediatric heart surgery: Physiological profiles and surgical complexity. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:620–8.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Brien SM, Jacobs JP, Pasquali SK, Gaynor JW, Karamlou T, Welke KF, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database Mortality Risk Model: Part 1—Statistical Methodology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manuck TA, Rice MM, Bailit JL, Grobman WA, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, et al. Preterm Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality by Gestational Age: A Contemporary Cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:103.e1–103.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagiub M, Kanaan U, Simon D, Guglani L. Risk Factors for Development of Pulmonary Hypertension in Infants with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Paediatr Respir Rev 2017;23:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heching HJ, Turner M, Farkouh-Karoleski C, Krishnan U. Pulmonary vein stenosis and necrotising enterocolitis: Is there a possible link with necrotising enterocolitis? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F282–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cory MJ, Ooi YK, Kelleman MS, Vincent RN, Kim DW, Petit CJ. Reintervention Is Associated With Improved Survival in Pediatric Patients With Pulmonary Vein Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1788–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.