Abstract

Friendship is a relationship that can endure across the entire lifespan, serving a vital role for sustaining social connectedness in late life when other relationships may become unavailable. This article begins with a description of the importance of studying friendship in late life and the benefits of friendship for older adults, pointing to the value of additional research for enhancing knowledge about this crucial bond. Next is discussion of theoretical approaches for conceptualizing friendship research, followed by identification of emerging areas of late-life friendship research and novel questions that investigators could explore fruitfully. We include a presentation of innovative research methods and existing national and international data sets that can advance late-life friendship research using large samples and cross-national comparisons. The final section advocates for development and assessment of interventions aimed at improving friendship and reducing social isolation among older adults.

Keywords: Friendship data sets, Friendship in old age, Friendship interventions, Friendship processes, Friendship research methods, Friendship structure, Friendship theory

Translational Significance

Social isolation places older adults in jeopardy for both poor health and low psychological well-being. Detailed research findings on crucial elements of friendship in late life can inform the design of social interventions aimed at enhancing personal skills and strategies for making and keeping friends, planning of community programs to foster friend interactions and advocacy for policies that promote rather than interfere with late-life friendship.

Why Is It Important to Study Friendship in Late Life?

What Are the Benefits of Friendship to Old People?

Friendship is a relationship that can endure across the entire life span, serving a vital role for sustaining social connectedness in late life when other relationships, such as with coworkers and organization members, may be relinquished. Although gaining new kin is common at earlier ages, in the later years the possibility of making new friends is greater than the likelihood of enlarging the kin network, at least in one’s own generation.

Friend ties have been revered as vital relationships since ancient times, when Confucius and Aristotle extolled the benefits of associating with those who encourage moral virtue, complement one’s own limitations, and provide cherished companionship. Aristotle, in particular, highlighted emotional and reciprocal aspects of friendship that are deemed important now (Mullis, 2010), as contemporary adults focus on affection, trust, commitment, respect, reciprocity, and the like when defining friendship (Blieszner & Adams, 1992; Dunbar, 2018; Felmlee & Muraco, 2009). At the same time, diversity in perceptions of important elements of friendship occurs across life cycle stage, gender, marital and parental status, geographic location and cultural context, and historical eras (Adams, Blieszner, & de Vries, 2000; Blieszner & Adams, 1992; Gillespie, Lever, Frederick, & Royce, 2015). Early empirical studies of social relationships, including those in late adulthood, generally did not focus on friendship per se, so this nuanced awareness of friendship is a recent phenomenon.

Although it is clear that friendship has long been an important part of social life and important to well-being, this close relationship has not received nearly as much attention historically as family ties. In fact, in 1950s and 1960s when sociologists and family scientists examined close relationships, they tended to investigate marital and kin bonds, but typically did not include friends in their studies. Not until 1970s and 1980s did scholars begin to probe friendship as a social role in its own right, separate from ties with colleagues, neighbors, acquaintances, and other nonkin, and to study friendship as a relationship rather than friendliness as an individual attribute. They uncovered a range of friendship forms and functions and identified both unique aspects of friendship as distinct from other ties as well as similarities between friendship and other informal and close relationships (Blieszner & Adams, 1992).

Studies consistently show that friend relationships are as important as family ties in predicting psychological well-being in adulthood and old age (Chen & Feeley, 2014; Dunbar, 2018; Santini, Koyanagi, Tyrovolas, Mason, & Haro, 2015). Of course, the closeness of both relatives and friends varies, so studies examining specific relationships as opposed to global categories are especially helpful for understanding the relative impact of family members versus friends on well-being in the later years. For example, analyses by Lee and Szinovacz (2016) of 6,418 participants in the 2008 Health and Retirement study showed that although relationships with spouses tended to have the strongest association with mental health, ties with friends showed stronger associations with mental health than those with other relatives. Results such as these suggest the merits of investigations specifically addressing friendship and specifically focusing on old age.

Along with investigation of structural aspects of friendship, such as friend roles and interaction frequency, came awareness of the need to examine friendship in the context of social networks; to view friendship as evolving over the life course and proceeding through phases over time; and to assess cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes as dynamic aspects of friend interactions. This more nuanced approach to friendship research emerged from moving beyond laboratory experiments and broad surveys to using in-depth interviews, which fostered a focus on quality of friend interactions, not just quantity (Adams & Blieszner, 1994; Blieszner & Adams, 1992) and recognition that friends and interactions with friends involve individual characteristics that evoke differential responses according to individual preferences (Adams & Blieszner, 1995). As a result, research on friendship has flourished in recent decades, including studies of friendship in middle-age and beyond, yielding a wide-ranging literature on both traditional (e.g., emerging from face-to-face interactions) and innovative (e.g., formed via social media networking) aspects of friend ties in later life (Blieszner & Ogletree, 2018).

Among the friendship and aging topics investigated, a prominent focus has been on the contributions of friends to psychological well-being (Blieszner, 1995; Blieszner & Ogletree, 2018). Late-life adults report liking and caring about their friends, laughing together and having fun, feeling satisfied with their relationships, being able to confide in each other, and reminding each other to stay healthy (Blieszner & Adams, 1992). Friend ties alleviate loneliness (Chen & Feeley, 2014; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, 2017), offer emotional and instrumental support (Felmlee & Muraco, 2009), and provide companionship through mutual interests and shared activities (Huxhold, Miche, & Schüz, 2014). The feelings of connectedness that these aspects of friendship convey give meaning to older adults’ lives, which is important for well-being (ten Bruggencate, Luijkx, & Sturm, 2018). Indeed, exchanging many forms of social support is one of the most important benefits of friendship in the second half of life.

The advantages of late adulthood friendship reach beyond psychological well-being. Research shows that relational closeness and social support are also important for maintaining cognitive functioning and physical health in old age (Béland, Zunzunegui, Alvarado, Otero, & del Ser, 2005; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). Moreover, old age poses unique challenges, including health changes that might require assistance or caregiving. Thus, it is particularly important to study old age friendships, especially for those without family members, without proximal family members, or without family members willing to care for them. Indeed, some friends do assume direct caregiving responsibilities (de Vries, 2018), particularly among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults who might experience strain in their family relationships (Muraco & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2011).

Although we can point to extensive evidence on the importance and benefits of friendship, unexplored research questions about friendship across the adult years abound. Key purposes of this article are to provide a comprehensive yet flexible conceptual framework to guide research on late-life friendship, synthesize into one framework the multiple aspects of friendship and its predictors suggested by various theoretical approaches, point to unanswered questions and useful research methods, and suggest friendship-related interventions that could successfully enhance experiences of friend partners in their special bonds. Our goal is to encourage scholars to study this rich and fascinating dimension of aging and engage in relevant translational science to sustain and enhance the quality of life for all elders. We begin with an examination of theories for investigating friendship.

What Theories Can Guide Friendship Research Toward Answering Unresolved Questions?

Foundational Theories

Although many theories of interpersonal attraction and relationship development could inform late-life friendship research, relatively few have guided these investigations. Social network theory, which focuses on predictors of the structure of relationships rather than on their dynamics, is relevant to understanding friendship opportunities and constraints at any stage of life. Relatively little is known about structural features of friendship dyads and networks, though, because empirical studies guided by social network theory usually have not distinguished between friends and other close ties. Nevertheless, some research on structural features of late-life friendship exists. For example, Adams (1987) studied changes in the friend networks of old women over 3 years and found interesting patterns of both expansion and contraction (not only contraction) of the network membership and also intensification and weakening (not only weakening) of emotional bonds among friends in the network. These changes in network size and closeness varied by the women’s demographic characteristics, namely social and marital statuses. Looking at additional structural features of late-life close friend networks, such as similarity of gender, race, religion, age, and extent of influence on the friend, Adams and Torr (1998) found variation in friend networks of both older women and men based on characteristics of the social and cultural environments in which the networks were embedded. This finding shows that friend bonds are affected not only by personal choice, but also by external influences. Thus, investigations of structural features of friend networks reveal the range of similarities and differences across groups of older adults based on cultural contexts, personal characteristics, and situational features of interactions with current or potential friends.

Social exchange theory, the convoy model of relationships, and socioemotional selectivity theory have been the most common guides for research on the processes of friendship development and sustainment. Early studies of friendship dynamics in old age were grounded in social exchange theory (e.g., Roberto, 1989; Roberto & Scott, 1986), which posits that social interactions involve costs and benefits that participants assess as they establish and sustain relationships. The types of resources exchanged (Blieszner, 1993; Shea, Thompson, & Blieszner, 1988) and the preferred and actual extent of equity and reciprocity in social exchanges (Dunbar, 2018) are also considered in friendship research conducted from this perspective. Li, Fok, and Fung (2011) examined age group differences in the association between emotional and instrumental support balance in relation to support received from friends versus family, and the implications for life satisfaction. Friendships were evaluated by older and younger adults as more reciprocal than family ties, in keeping with the more voluntary nature of friendship. However, older adults reported higher life satisfaction when they felt emotionally (but not instrumentally) over-benefited in friendships, whereas younger adults’ life satisfaction was associated with reciprocity in emotional support exchanges with friends. The general assumption that equity in exchanges is preferable did not apply to the older adults in this study, reflecting the premises of socioemotional selectivity theory, discussed later.

The convoy model of relationships (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987) provides another approach to analyzing old age friendship and support interactions, connecting both interactive and structural aspects of relationships. It focuses on differences in perceived level of closeness, allowing for comparisons across types and functions of friendships as well as across stages of the life span (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1995). Using the convoy model, Piercy and Cheek (2004) investigated friendships among middle-aged and older women who belonged to quilting bees and guilds. They found evidence of strong and supportive friend convoys with interaction patterns suggesting these friends would have enduring positive effects on the women’s well-being into oldest age. Levitt, Weber, and Guacci (1993) examined social support (e.g., confiding, reassurance and respect, assistance, advice) from friends versus relatives across the social network structures of family triad members from three generations. The mothers and grandmothers tended to report fewer friends than relatives in their networks and to receive less support from friends as compared with the youngest women. This pattern held across cultures, as both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women reported similar network structures and sources of support. A recent meta-analysis by Wrzus, Hänel, Wagner, and Neyer (2013) confirmed these cross-generational differences in network structure (i.e., size) via a meta-analysis of data in 277 studies from 28 countries.

More recently, socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles (1999) has underpinned research on friendship in the later years. This theory proposes changes in social interactions as older adults perceive their remaining lifetime becoming shorter. Specifically, old people adapt to their changing circumstances by reserving their emotional energy for their most important relationships, shedding those with less meaning and value. Sander, Schupp, and Richter (2017) found support for this theory in a study of German adults aged 17–85. Across age groups, the frequency of face-to-face contacts with relatives was similar, but such interactions with friends and others decreased in frequency. The study by Li and colleagues (2011) described previously also confirmed socioemotional selectivity theory, with findings suggesting that older persons in the study had higher life satisfaction in the context of nonreciprocal emotional support, probably because they prioritize emotionally meaningful exchanges over other interactions. These findings imply that very close friends can continue as central figures in older adults’ social networks even if the networks are shrinking, regardless, perhaps, of frequency of face-to-face contact.

An Integrative Conceptual Framework

Social network theory highlights the value of examining structural features of friendship, how they influence formation and retention of friendships, and whether those features change over time. Social exchange, convoy, and socioemotional selectivity theories share similar foci on availability and reciprocity of support in friendship and other close relationships. They point to numerous individual, interpersonal, and interactional characteristics that can have an impact on friend relationships and outcomes. Our conceptual framework for friendship research (Adams & Blieszner, 1994; Adams, Hahmann, & Blieszner, 2017; Ueno & Adams, 2006) integrates the psychological and sociological perspectives highlighted in social exchange, convoy, socioemotional selectivity, social network, and other theories to provide a flexible and comprehensive guide for investigating many intersecting dimensions of friendship in old age. Propositions and hypotheses from the focal theory can be formulated around the concepts and variables identified in the friendship framework.

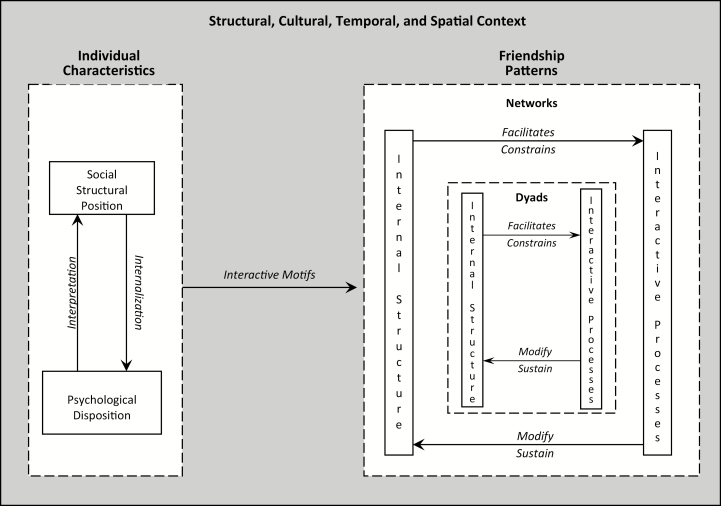

As shown in Figure 1, the integrative friendship framework posits a series of reciprocal influences on friend partners that affect their typical modes of interacting and hence, their emergent and ongoing interaction patterns. The gray box and arrows signify that friendship patterns are dynamic and contextualized in time and space and across cultures; the dashed lines signify that individuals, friend dyads, and friend networks embedded in these contexts affect them and are affected by them. The left panel shows that friends bring their individual characteristics to the relationship, including both social structural positions and psychological dispositions, which are mutually influential through the social psychological interpretation and internalization processes described by Cooley and Mead (Adams & Blieszner, 1994; Cooley, 1964; Mead, 1962). That is, propensities emerging from socialization experiences and personality affect how a person internalizes expectations associated with specific social locations, and social locations affect how a person interprets friendship-related opportunities and constraints. These personal characteristics lead to choices about where to spend time and how and when to interact with friends, as well as ways of thinking and feeling about friends and friendship, signified as interactive motifs and depicted in the middle of the figure. Cognitive, affective, and behavioral interactive motifs thus affect the friendship patterns (right panel) that occur between friend pairs and in larger friend networks in which the pairs are embedded. For either friend dyads or friend networks, internal structural features (homogeneity and hierarchy in dyads; size, density, homogeneity, and hierarchy in networks) facilitate and constrain interactive processes (cognitive, affective, behavioral), which in turn modify or sustain the internal structural features.

Figure 1.

Integrative conceptual framework for friendship research. From Ueno and Adams (2006), reprinted with permission from Routledge Publishing, Inc.

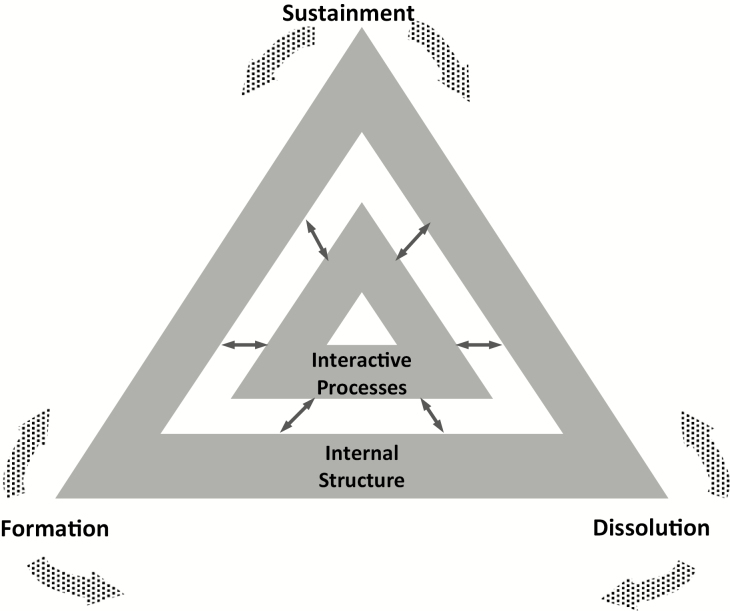

Friendships are not static, so Figure 2 demonstrates that the patterns exhibited in Figure 1 occur across the phases of friendship formation, sustainment, and dissolution. Friendships have a starting point, they can become closer or less close, and sometimes they end (Adams & Blieszner, 1994, 1998; Blieszner & Adams, 1992, 1998). Use of the term phases avoids the notion of unidirectional stages of relationships, which does not apply well to friendship. Rather, movement across phases of friendship is fluid and potentially bidirectional. For example, an incipient friendship might wax and wane in the formation phase before becoming solidified as an ongoing friendship, or a dissolved friendship might be resumed later. Within any of the phases, closeness and other process aspects could increase, decrease, or remain stable. Finally, transitions across phases are influenced by internal structural features and interactive processes.

Figure 2.

Friendship phases: changes over time in internal structure and interactive processes.

Studies Illustrating Elements of the Friendship Framework

The most common structural dimensions examined to date are friendship network size and frequency of contact (which is merely a proxy for interactive processes, revealing existence of connections, but nothing about the type or quality of the interactions). The typical interactive dimensions appearing in late-life friendship research are behavioral processes, such as provision of instrumental, emotional, and social support. Few investigators have examined the phases of friendship in late life intentionally and systematically.

Examples of research investigating structural aspects of friendship appear in the meta-analysis of social network size by Wrzus and colleagues (2013) described previously. They found reliable cross-cultural evidence that friendship networks decrease in size across the years of adulthood. Social structural position includes age group, and Wrzus and colleagues noted that both normative and nonnormative life events occurring at different ages have an impact on the friend network as needs, other relationships, and life circumstances modulate social interactions. Indeed, Litwin and Shiovitz-Ezra (2006) found that being embedded in friend-focused networks was a protective factor against mortality risk for older adults and de Vries, Utz, Caserta, and Lund (2014) found that friends were particularly helpful in providing social support and assistance in early widowhood.

Focusing on psychological disposition, Lecce and colleagues (2017) showed that individual differences in theory of mind skills (extent of awareness that thoughts, beliefs, and emotions affect social interactions) were associated with differences in friend but not family ties among older adults in Italy. Moreover, this theory of mind effect was moderated by social motivation (in this study, the importance of being liked by others), such that it occurred only for those who had a high or medium level of social motivation. Thus, understanding others and being motivated to use social skills to foster positive relationships influence friendship outcomes. Looking instead at the impact of one’s perceptions of aging on friendship outcomes and employing a longitudinal design, Menkin, Robles, Gruenewald, Tanner, and Seeman (2017) found that holding more positive expectations about aging to begin with was associated with greater perceived availability of social support from friends a year later and with having made more new friends, with more of them close, 2 years later. Thus, these findings showed that a personal attribute influenced cognitive, behavioral, and affective friendship processes, respectively over time.

Research on friendship phases as depicted in Figure 2—how older adults form, sustain, and dissolve friendships—is scarce. Piercy and Cheek (2004) noted that quilting provided a context for older women to make new friends and Menkin and colleagues (2017) noted existence of new friends, but these researchers did not delve into aspects of interaction that contributed to older adults moving from being acquaintances to being friends. Insight into this phase transition comes from Blieszner (1989) and Shea and colleagues (1988) who reported on friendship initiation over 5 months among strangers who relocated simultaneously to a newly constructed retirement community. Key contributors to initiation phase transitions involved changes in feelings and activities. Spending time together in mutually appealing activities increased feelings of liking, loving, and commitment to the friendship. These affective processes built trust and promoted ongoing exchanges of social and instrumental support.

Blieszner (1989) and Shea and colleagues (1988) also found examples of older adults’ efforts to sustain both the new and previously existing friendships through expressing affection, disclosing personal information and feelings, helping one another, and engaging in activities together. Another example of activities and feelings that sustain friendship comes from a study of old male veterans by Elder and Clipp (1988). They discovered that the process of veterans sharing memories of their intense combat experiences and losses with veteran friends served to perpetuate these very long-term friendships.

Finally, in a randomly selected sample of adults aged 55 and older (n = 53) and data from face-to-face interviews, Blieszner and Adams (1998) inquired about dissolution-related phases of friendship. Some friendships were fading away (mentioned by 68% of participants), either because of circumstances unrelated to the dyad, such as relocation of one partner, or because one friend was intentionally letting the friendship drift apart due to a problem in the relationship. In addition, a small proportion of participants (25%) had ended a friendship intentionally, usually because of betrayal. As these research examples show, structural, cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects of friendship interactions all came into play in the formation, sustainment, and dissolution phases of friendship.

The literature also contains studies relevant to the integrative friendship framework that address multiple dimensions simultaneously. Although we did not intend the friendship framework to be predictive, an early operationalization of one component shown in Figure 1 was conducted by Dugan and Kivett (1998). Using a sample of 282 rural and urban adults aged 65–97 years, they sought to determine whether personal characteristics and behavioral motifs predicted interactive processes. Results of regression analyses showed that two personal characteristics (gender and education) predicted affective and behavioral processes; behavioral motif as indexed by social involvement in clubs, hobbies, and volunteerism, predicted behavioral processes but not affective or cognitive ones; and proximity predicted all three interactive processes. The effect of cultural context, assessed by rural or urban residence, was not significant in this sample. Although this research employed one part of the framework to predict other parts, the work of other investigators illustrates the application of framework components in studies of a diverse array of outcome variables.

Using data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, Kahn, McGill, and Bianchi (2011) addressed the intersections of individual characteristics (age and gender) with the friend and other nonkin behavioral interactions (providing assistance) over time. Women were more likely to provide emotional support and men were more likely to provide instrumental support. Both women and men with more resources (e.g., more education) were more likely to provide help, and after retirement or widowhood, men increased their help giving.

Dunbar (2018) provided an overview of research illustrating the intersection of friendship structure at the dyadic and network levels with cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes. Emotional closeness affects the likelihood of engaging in companionship and sharing the social and psychological support that typically define friendship. Because developing emotional closeness and trust requires a significant time investment, the number of people in one’s circle of closest friends is limited. Moreover, cognitive processes—assessing implicit social contracts related to assumptions of ongoing support, inhibiting some of one’s own preferences and behaviors to enable friends to satisfy theirs, and the perspective-taking that fosters understanding of friends’ needs and motives – are crucial for establishing and sustaining emotionally close and satisfying friendships.

As these examples of late-life friendship research show, the integrative conceptual framework supports examination of myriad intersecting dimensions of friendship and its outcomes in a systematic way. Combining this framework with relationship theory permits development of hypotheses to evaluate, and also can illuminate the more subtle influences on friendship that warrant investigation.

What Novel Aspects of Friendship Demand Scholarly Exploration?

Despite a breadth of research on social networks across the life course, friendship in the second half of life remains underexplored when compared with information about kin relationships. Moreover, the entrance of new cohorts into old age along with social and cultural change over time suggests the need to examine new dimensions of late-life friendship. This section provides a brief overview of research questions that remain unanswered and are now ripe for further exploration.

Friendship, Health, and Well-Being

Much contemporary research has focused on contributions of friends to health and psychological well-being among older adults. At the structural level of analysis, for example, Sander and colleagues (2017) documented a connection between social contact frequency and health across adulthood. Visits with nonfamily members declined over the study waves relative to family visits, with an indication that poorer health in old age explains the less frequent visiting with friends, neighbors, and acquaintances exhibited at that stage of life.

Provision of social support is the most common behavioral process examined in old age friendship research. A useful resource for data on the connection of social support from friends and others and health with well-being outcomes is the review article by ten Bruggencate and colleagues (2018). These authors analyzed how having social needs satisfied is a protective influence on the health and well-being of old people. Unmet social needs can lead to loneliness and social isolation, which in turn can cause health to decline. In contrast, older adults with strong ties to family and friends are more likely to retain independence, a sense of meaning and purpose in life, and effective physical and psychological functioning longer. Thus, understanding the connection between friend support and psychological problems such as depression is important for promoting health and well-being among older adults.

A review of 51 studies (published between 2004 and 2014) of associations among social support, social networks, and depression from around the world by Santini and colleagues (2015) confirmed that perceived emotional support within large and diverse social networks is protective against depression, as is perceived instrumental support. More research is needed, however, particularly prospective studies, to tease out causality in the associations among social support, social networks, and depression. Are those with fewer depressive symptoms better able to secure large friend networks and receive support than persons exhibiting depression? Is greater availability of social support from a robust social network protective against the development of depressive symptoms?

Being engaged in a friend network can also buffer the effects of life events that may occur in old age. Marital status has traditionally been used as a benchmark for well-being, so comparing the associations of marital status, friendship, and well-being is one approach to understanding the role of friends in buffering the effects of negative life events. Studies in this domain contrast friendship effects among married old people, those who are formerly married, and those who never married, at least in the traditional sense. They also illuminate variation in friendship structure and processes across different subgroups of the older adult population.

Han, Kim, and Burr (2017) used longitudinal data from the Health and Retirement Study to examine the connection between friendship and depression among married couples. Partners who had more frequent social interactions with their friends reported fewer depressive symptoms than those with fewer friend interactions, particularly in the context of poorer marital quality. Moreover, dyadic growth curve models showed that one partner’s responses to friendship had implications for the well-being of the other one, demonstrating that the effects of friendship extend beyond the focal person.

Concerning older adults who are no longer married, both de Vries and colleagues (2014) and Bookwala, Marshall, and Manning (2014) studied friendship in the context of marital loss through widowhood. The findings from de Vries and colleagues showed that higher friendship satisfaction was associated with more positive self-evaluation and more positive affective responses in the first half year of widowhood, whereas Bookwalla and colleagues found that having a friend confidante helped mitigate depressive symptoms and promote better health as reported up to 12 years after spousal loss.

Examination of friendship among committed partners comes from the work of Kim, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Bryan, and Muraco (2017) who demonstrated the importance of large and diverse social networks, including the availability of friends, for mental health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Although these elders may not have as many family ties as others, having supportive social ties within friend networks are as essential for them as for anyone in preventing social isolation and reducing the likelihood of depressive symptoms.

However, marriage is not the only context in which friendship affects psychological well-being. Other structural factors besides marital status, such as cultural background, gender, racial ethnic status, and socioeconomic status, no doubt influence friendship opportunities and constraints that affect social integration or isolation and psychological well-being or depression. Research on the friendship patterns of such subgroups in the older adult population remains to be conducted. The integrative conceptual framework for friendship research offers guidance for investigating the effects of social locations and personality characteristics on friendship patterns.

Another perspective on the connection between friendship and well-being in old age is related to the notion that relational partners are interdependent; the actions of one affect the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of the other (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). Thus, life events can have an impact not only on oneself, but also on one’s friends, leading to research questions such as whether someone’s misfortune rallies friendships or drives friends away. Indeed, Breckman et al. (2018) reported that family and friends who know about an older adult’s mistreatment also suffer distress, illustrating how friendship can have negative as well as positive impacts. However, this cross-sectional study did not follow the abuse victims and their social network members, so how the friends who knew about the abuse fared as time went on could not be assessed. What other personal events and circumstances that have not yet been examined for impact on others might interfere with friendship or be buffered by friendship support?

Friendship and Caregiving

Another crucial focus for contemporary friendship research is the contributions of friends to providing care for older adults. Given that offspring and other relatives may live a great distance away from loved ones who require assistance and caregiving, the potential for local friends to fill in when frailty emerges needs systematic examination. Questions about interest in helping one’s friends in this way and willingness to provide more than casual support, and questions about the efficacy of friend caregiving, remain largely unanswered.

Lilly, Richards, and Buckwalter (2003) found that some caregivers of loved ones with dementia mentioned the value of their friends in providing the caregivers with emotional support and social integration. No doubt, those helpful friends buoyed the family caregivers as they dealt with memory loss. Of course, friends are not always helpful, as Abel (1989) noted. In her interviews with adult daughters caring for frail elderly parents, some of the participants pointed out that friends (and relatives) often exacerbated caregiving stress instead of alleviating it, such as by trivializing the difficulties of caregiving. This type of research, however, does not focus directly on care provision by friends. In fact, most caregiving studies do not differentiate across family and friends when examining helpers for older adults. Our literature search on studies related to “friends and caregiving” uncovered 33 articles published since 2012, but all the analyses combined responses for relatives and friends. Therefore, whether it is practical for health care workers to involve friends in care planning, particularly when relatives do not live nearby, merits additional scholarly attention.

Friendship in the Digital Age

A clear avenue for innovative friend research is the inclusion of communication technology and social media as mechanisms for understanding how older adults establish and sustain friendships throughout adulthood. Current findings on Internet use and social media use through websites such as Facebook indicate that older people are less likely than their younger counterparts to be frequent users (Barbosa Neves, Fonseca, Amaro, & Pasqualotti, 2018; Cotten, McCullouch, & Adams, 2011; Yu, Ellison, & Lampe, 2018). However, older people are adopting technology to sustain social relationships (Tsai, Shilliar, & Cotten, 2017) and keep in contact with friends and relatives who may be geographically distant (Tsai, Shilliar, Cotten, Winstead, & Yost, 2015). Internet use, for example, is associated lower rates of depression and loneliness (Cotten, Ford, Ford, & Hale, 2012) and greater levels of social capital (e.g., quality and quantity of social ties) when compared with adults who did not use the Internet at all or who used it less frequently (Barbosa Neves et al., 2018).

Additional research shows that older Facebook users have smaller numbers of online “friends” but a greater proportion of actual friends than younger Facebook users (Chang, Choi, Bazarova, & Lockenhoff, 2015; Yu et al., 2018), a finding consistent with socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen et al., 1999). Given the prevalence of social media, it is important that future work examines the extent to which virtual social networks complement actual friend networks and the types of support exchanged with both types of friends. Will friend networks become increasingly more diverse, including friends both in-person and online, proximal and distal? Will friendships last longer, reducing relationship dissolution, due to the ease of connection among long-distance older persons? Will social media influence the ways in which old people engage in friendship? Will completely virtual friendships interactions differ from past patterns in which friendships typically began with face-to-face interactions even if they were sustained over long distances via mail and telephone? Research on social media use among older adults is still in its infancy and will be a burgeoning area of research as digital natives age into midlife and beyond.

Friendship in the Age of the Brain

An additional area of innovation for friend research is the association between friendship and cognitive functioning. Our review of the literature yielded few studies that explicitly explored this topic, which contrasts with the preponderance of research on general social resources and cognitive functioning in old age (Kuiper et al., 2016). The longitudinal study by Béland and colleagues (2005) showed that having friends was associated with slower cognitive decline in women but not men over the course of 7 years. Béland and colleagues argued that this finding might be due to women’s gender-based social roles that necessitated greater social integration over the years. A more recent study by La Fleur and Salthouse (2017) found that contact with friends, but not family, was positively associated with general intelligence. However, this finding approached nonsignificance after examining the effects of education, suggesting that individuals who are better educated spend more leisure time with friends.

These studies illuminate a path forward for friend research and lead to the following questions: How might cognition and, specifically, problem-solving skills and inhibitory control relate to the quality of interactions between older adult friends? For example, research demonstrates that inhibitory control is negatively associated with impulsivity (Logan, Schachar, & Tannock, 1997), while additional research documents that impulsivity is related to negative interpersonal encounters in young adults (aan het Rot, Moskowitz, & Young, 2015). Are older adults with poorer inhibitory control more likely to report negative interactions with friends? Conversely, are those with better inhibitory control more likely to report positive interactions with friends? Similarly, problem-solving skills are associated with memory, reasoning, processing, and global mental status; each of these domains is related to everyday functioning among older adults and translates to performance on common instrumental activities of daily living (Gross, Rebok, Unverzagt, Willis, & Brandt, 2011). If a key domain of adult friendship is the exchange of instrumental and emotional support, then more research is needed to document the implications of cognition in late-life behavioral friendship processes.

Friendship as a Unique Relationship

Innovative findings on late-life friendship might also be uncovered through the intentional inclusion of friend-related variables as separate from family and neighbor relationships. For example, research on social relationships among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) older adults has focused on the importance of friendship in aging, commonly using language such as “chosen families” (de Vries & Megathlin, 2009). The same attention to the value of friendship in aging has not been applied in non-LGBT research. This gap in the literature implies that scholars presume the presence and supremacy of biological kin networks in old age, thus ignoring the value of non-biological relationships. Investigators have used the ambiguous grouping of friend relationships into categories, such as “friends/neighbors,” “friends or other relatives,” and “social resources,” with the latter going so far as to subsume all social relationships into one undifferentiated group. Yet research clearly shows that friends, neighbors, and kin relationships provide varying levels and types of support. For example, LaPierre and Keating (2013) found that among 324 nonkin caregivers, friends provided help with personal care, bills, banking, and transportation whereas neighbors were more likely to help with less personal tasks such as home maintenance. Further, friends were more involved in providing care for nonkin than neighbors were and assisted care recipients with a greater number of tasks for more hours per week. Such research indicates that friends are unique voluntary relationships that are more intimate than more emotionally distal ties that might occur with neighbors. Moreover, friends often contribute more positively to psychological well-being than family relationships do (Huxhold et al., 2014). Thus, it is imperative that future research on older persons’ social network members focus specifically on friendship as a unique relationship and distinguish differential structures, functions, processes, and phases across types of relationships in great detail.

What Innovative Designs and Technologies Would Reveal Untapped Elements of Friendship and Its Value?

We identified three main ways in which friendship research might be advanced, thus revealing untapped elements of friend relationships and their value. First, more research is needed that goes beyond the structure of friendship (“How many close friends do you have?”) to explore interactive processes that convey deeper perceptions of, feelings about, and activities within older adult friendships—their cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions. Second, studies of friendship have been conducted in regional and cultural silos that were not being translated across disciplines and cultural boundaries. Third, most studies of friendship have incorporated cross-sectional designs, inhibiting understanding of changes and stability in friendship over the adult lifespan.

These three current limitations point to the value of linking Adams and Blieszner’s (1994) integrative conceptual framework for friendship with data harmonization techniques that permit combining regional, national, and international data sources. For example, Hofer and Piccinin (2010) described the potential for integrating multiple levels of analysis, theories, and designs to enable synthesis of results across multiple data sets, including longitudinal studies of aging, to broaden the scope of research on a given topic; Survey Research Center (2016) provided detailed guidelines for such work. Existing longitudinal data sets could be exploited for secondary analyses using Adams and Blieszner’s framework for guidance on the variable selection, thus enabling scholars to uncover prevailing trends in friendship as well as idiosyncrasies across data sources and across cultures and time.

To prompt this new kind of friendship research, we offer an analysis of the potential for finding structural, cognitive, affective, and behavioral variables as enumerated in the Adams and Blieszner (1994) conceptual framework within regional, national, and international data sets. First, we used the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research to conduct a search of studies that included middle-aged and older adults. We then examined each data source for friendship variables and, for those that included friend variables, reviewed their list of publications for studies with friends as a focal topic. We also searched the major gerontological and relationship journals for articles related to older adult friendship and reviewed their data sources. This process yielded 11 large-scale longitudinal data sets suitable for pursuing cross-national and longitudinal research on adult friendship. The data sets are (1) Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL); (2) The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA); (3) Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA); (4) Longitudinal Study of Generations (LSG); (5) Swedish Adoption/Twin Study on Aging (SATSA); (6) Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS); (7) National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP); (8) Health and Retirement Study (HRS); (9) Midlife in the United States (MIDUS); (10) Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE); and (11) German Ageing Survey (DEAS).

Next, we classified each data source’s friend-related questions and variables according to the Adams and Blieszner (1994) integrative conceptual framework, as shown in Table 1. For reference, we also included the Adams and Blieszner Andrus Study of Older Adult Friendship (Adams & Blieszner, 1993a), which guided the formulation of the integrative conceptual framework for friendship and provides examples of structural, cognitive, affective, behavioral, and phase questions. Note that the information presented in this table is not exhaustive of each data source’s friend-related questions; rather, it highlights questions corresponding to the integrated conceptual framework for friendship. The variables derived from these questions could be addressed by data harmonization processes to enlarge the size of samples and scope of variables available for analysis of cognitive, affective, and behavioral friendship processes and phases over time and across cultures.

Table 1.

Friendship Variables in Regional, National, and International Data Sets

| Ages (N) at Wave 1 | Examples of friendship variables/questions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | Years | Friendship structure | Cognitive processes | Affective processes | Behavioral processes | |

| Andrus Study of Older Adult Friendship (Adams & Blieszner, 1993a) |

1993 | 55–84 (N = 53) | “How many friends do you have?”; “How close are you with [close friend]? [very close, close, or casual]”; “How far do you live from [close friend]?”; “How long have you been friends?”; “How similar are you and [close friend]?” | “How willing would [friend/s] be to provide help if needed?”; “How important are [attitudes, values, and characteristics] of friends?” | “How do you feel about [different types of friends in friend network]?”; “How do you feel when....?”; “What are your feelings regarding relationships that are changing or fading?” | “Has [friend name] done a favor/provided advice or support?”; “What do you think are some barriers to seeing or talking with [friend]?”; “How frequently do you [communicate] with [friend]?”; “How do you resolve conflict and disagreements with [friend]?” |

| Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL)a | 1986, 1989, 1994, 2002 | 25+ (N = 3,617) in 1986 | “About how many friends or other relatives do you have whom you could call on for advice or help if you needed it?” | “In your lifetime, have friends gotten more important, less important, or stayed the same [in importance]?” | — | “How often do you talk with friends, neighbors, and relatives in a week?” |

| The Irish Longitudi- nal Study on Ageing (TILDA)b | 2009–2011 | 50+ (N = 8,504) in 2009 | “In general, how many close friends do you have?”; “Have any of your close friends died in the past five years?” | “How much do they [friends] really understand the way you feel about things?” | “How much do they [friends] get on your nerves?” | “In the last two years, did your neighbors or friends give you any kind of help...” |

| Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA)c | 1992, 2002, 2012, 2015 (on-going) | 55–84 (N = 3,107) in 1992 | “How many years have you known [friend]?”; “How long does it take you to travel to [friend]?”; “How often are you in touch with [friend]?” | — | — | “How often did it occur in the last year that [friend] helped you with daily chores in and around the house...?”; “How often did it occur in the last year that you quarreled with [friend]?” |

| Longitudinal Study of Generations (LSG)d | 1971, 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 2000, 2005 | 60s (Grandparents) 40s (Parents) 15–26 (Grand- children) (N = 300 families) in 1971 | “How many close friends do you see or hear from?” | “Please compare your political views with your close friends’”; “How important is your role as friend?”; “Rank your quality of performance in your role as a friend.” | “How satisfied are you with the amount of contact with your close friends?” | — |

| Swedish Adoption/ Twin Study on Aging (SATSA)e | 1984, 1987, 1990, 1993, 2003, 2007, 2010 | 26–93 (N = 2,018) in 1984 | “How many friends do you have that can visit you, or who you can visit, anytime and feel right at home?”; “How often do friends visit?” | — | “Are you satisfied with support from friends?” | — |

| Wisconsin Longitudi- nal Study (WGS)f | 1957, 1964, 1975, 1992, 2004, 2011 (on-going) | 17+ (N = 10,317) in 1957 | “Could you give me the names of some of the [same-sex friends] who were your best friends in your senior class in high school?”; “Think back to 1957...what was the name of your closest...friend?”; “During the past 12 months, how often did you have contact with [friend]?” | “Overall, how do you think you compare with [friend]?” [In reference to work, education, and finances] | “How much do [friends and relatives] make you feel loved and cared for? | “Is there a friend outside your family with whom you can share very private concerns?”; “How much are they [friends and relatives] critical of what you do?” |

| National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP)g | 2005–2006, 2010–2011, 2015–2016 (on-going) | 57–85 (N = 3,005) in 2005–2006 | [Social network approach] “How frequently do [name from network] and [name from network] talk to each other?”; “About how many friends would you say that you have?”; “How close do you feel is your relationship with [name from network]?” | — | — | “How often do they [friends] make too many demands of you?”; “How often do they [friends] criticize you?” “How often can you rely on them [friends] for help if you have a problem?” |

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS)h | 1992, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 (on-going) | 51–61 (N = 12,652) in 1992–1993 | “How many friends would you say you have a close relationship with?” | “How much do they [friends] really understand the way you feel about things?” | “How much do they [friends] get on your nerves?” | “On average, how often do you do each of the following with any of your friends? (meet up, speak on the phone, write or email) |

| Midlife in the United States (MIDUS)i | 1995, 2004, 2011, 2013 | 25–74 (N = 7,108) in 1995–1996 | “Considering only friends you feel close to, how many friends do you have contact with at least once a month?” (2013 only) | “How much do they [friends] really understand the way you feel about things?”(all waves); “When I compare myself to friends and acquaintances, it makes me feel good about who I am.” (2004 only) | “How much do they [friends] get on your nerves?” (all waves); “I often feel lonely because I have few close friends with whom to share my concerns.” (2004 only) | “On average, about how many hours per month do you spend giving informal emotional support to each of the following people?” [including friends] (2004 only) |

| Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)j | 2004–2006, 2006–2010, 2011–2012, 2013, 2015 (on-going) | 50+ (N = 31,115 from 12 countries) in 2004 | “Who gave you help?” | — | — | “Which types of help has this person provided in the last twelve months?”; “In the last twelve months, how often altogether have you [or your partner] received such help from this person?” |

| German Ageing Survey (DEAS)k | 1996, 2002, 2008, 2011, 2014 (on-going) | 40+ (N = 4,838) in 1996 | “How often do you visit friends or acquaintances or invite them over to your home?”; “How has your relationship with friends or acquaintances changed over the past 6 years?”; “If you think about your friends and acquaintances, your family, and other people that you have everyday dealings with, which of these people do you spend most of your time with?” | “How much currently do you think of or do something about...” [satisfying friendships, social integration] | “Are there people [in your social network] who are causing you worry or concern? If so, who?”; “Are there people who give you great joy or happiness? If so, who?” | “Which person [in your social network] can you turn to when you need comfort or cheering up when you are feeling sad?” |

Note. Dates in italic font indicate verified availability of friend variables at that wave. Dates in roman font indicate either no verified friend variables or the questionnaire was not available in English.

Review of these longitudinal data sources demonstrates that, indeed, there is immense potential for the future of older adult friend research using data harmonization techniques. Almost all the data sources included questions about structural components of friendship, including number of friends or close friends. Descriptive analyses might reveal similarities or differences in the size and composition of friend networks across multiple countries and regions and changes in networks across stages of adulthood. For cognitive processes, most (7 out of 11) data sources included reflective or comparative questions in reference to friends. For example, three studies (TILDA, HRS, MIDUS) asked, “How much do [friends] really understand the way you feel about things?” Affective processes were assessed in 7 of the 11 studies, as well. Four studies (TILDA, HRS, MIDUS, DEAS) tapped negative dimensions of friend relationships, inquiring whether friends “get on [their] nerves” or were “causing worry.” Two studies (LSG, SATSA) evaluated satisfaction with friends, a positive feeling. Finally, most studies (9 out of 11) included questions that assessed behavioral processes, such as support exchanged, frequency of contact, and availability of support from friends. Two studies (WLS, NSHAP) asked the question, “How much/often do [friends] criticize you?” Conversely, four studies (TILDA, LASA, MIDUS, SHARE) evaluated actual support exchanged between friends.

Exploring these structural elements and cognitive, affective, and behavioral friendship processes across large cross-national data sources could reveal novel insights regarding friends and aging. Are there cultural differences in support exchanges or in the size, composition, and closeness of friend networks? What groups of older adults are more likely to experience negative interactions with friends and might these exchanges have implications for health over time by affecting the availability of supportive resources? Further, how do friendship processes change over time and across places? There are many paths forward for the future of friend research, but we believe that more robust use of existing data sources is a feasible next step. Moreover, newly launched studies should incorporate friend variables that assess nuanced dimensions of friendship processes and phases rather than focusing solely on structural components.

What Interventions Can Be Employed to Increase Satisfaction With Friend Relationships and Improve Friend Interactions?

In 1992, Blieszner and Adams described how programs affecting the friendship patterns depicted in Figures 1 and 2, and thus individual outcomes, could be implemented at the individual, dyadic, network, immediate environment, community, or societal levels. Although in a subsequent article Adams and Blieszner (1993b, p. 173) stated clearly that they did not “necessarily intend to advocate friendship intervention,” they conservatively cautioned policymakers, program planners, and human service providers not to design and implement interventions that would inadvertently undermine existing social relationships. The reasons for not fully endorsing friendship interventions at the time were twofold. First, research on friendship was not robust enough to suggest details of what sorts of interventions might be most needed, efficient, and effective. Second was recognition that friendships were culturally defined as voluntary and, though they are much more structurally constrained than many friends realize, some would find such interventions uncomfortable or inappropriate.

Although the friendship research literature is now more robust, the literature assessing the effectiveness of interventions is still scarce. Increased public focus on the consequences of loneliness and isolation is leading to more recognition of the necessity of promoting friendship, but systematic interventions into all aspects of friendship patterns described in the previous sections have not been introduced. That is, just as most research on friendship has focused on behavioral processes such as social support to the relative neglect of examining other behavioral processes as well as cognitive and affective processes, so too friendship intervention programs have emphasized behavioral strategies such as skill enhancement as approaches to developing friendships, with little attention to addressing the impact of thoughts and feelings on friendship interactions. Now that more recent research has demonstrated the importance of friendships to well-being, health, and longevity, it seems prudent to begin designing, intentionally implementing and assessing a broad range of friendship interventions among older adults. First, we present examples of research assessing intervention programs that address various parts of the integrative conceptual framework and levels of intervention, then cite literature pointing to other possibilities for enhancing friendship among older adults. This section ends with suggestions for enacting and assessing such friendship interventions.

Examples of Friendship Intervention Research

Stevens and colleagues in The Netherlands have been investigating intervention strategies for enhancing friendship at the individual level of analysis. For example, Stevens, Martina, & Westerhof (2006) showed that participating in a 12-week program designed to promote self-esteem (individual characteristic) and relational competence, social skills, and friendship formation skills (behavioral processes) enabled older women to establish new friendships and improve existing ones, thus reducing loneliness and improving well-being. These outcomes endured for at least a year. Building on that work, Martina, Stevens, and Westerhof (2012) used self-management of well-being theory to probe mechanisms underlying friendship-related improvements. Interview data from the intervention participants and control group members revealed that compared with control group members, women who completed the friendship enrichment program showed greater increases in behaviors related to taking the initiative and engaging in actions aimed at developing and improving friendships (behavioral processes). Extending the in-person friendship intervention approach to an online one, Bouwman, Aartsen, van Tilburg, and Stevens (2017) demonstrated the effectiveness of focusing on network development (structure), adapting personal standards for friendship, and reducing the salience of the discrepancy between actual and desired relationships (cognitive processes). Both follow-up studies showed continued promise for assisting old persons with honing friendship skills that can improve relationships and boost personal well-being. In related work, research by both Lecce and colleagues (2017) and Vargheese, Sripada, Masthoff, and Oren (2016) suggests interventions related to cognitive processes. The Lecce team focused on the importance of both increasing theory of mind skills, or the understanding of others’ mental states, and increasing social motivation to use those skills in friendship interactions, which could reduce loneliness and social isolation. The Vargheese group demonstrated that professionals can employ theoretically derived persuasive strategies to encourage older adults to participate in social activities.

Development and assessment of additional interventions addressing a broad range of affective, cognitive, and behavioral friendship patterns would offer more options for assisting lonely or isolated old people with improving their friendships. Acknowledging the dynamic nature of friendship, these programs should give attention to skills for initiating versus sustaining friendships, rejuvenation of faded friendships, and repair of problematic and conflictual ones.

Directions for New Friendship Interventions

Research on associations across older adults’ personal preferences for friendships and their social needs, health, and well-being point to many possibilities for friendship interventions related to the elements of the integrative conceptual framework for friendship research described previously. Earlier life experiences and current age-related life events can affect older adults’ social needs, their friend networks, and their friend-related cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes (Blieszner & Ogletree, 2017; Wrzus et al., 2013). Older adults vary with respect to the number and types of friends they prefer to have, whether they desire only close or more peripheral relationships, the importance they place on various friendship interaction processes and forms of social support, and the amount of reciprocity they expect among their friendships—and those preferences can change over time (Blieszner, 1995; ten Bruggencate et al., 2018). The contexts in which older adults are living, including the family versus friend composition of their social network, their residence (community-dwelling, assisted living, nursing home), and the presence or absence of socially isolating chronic health conditions, also affect their needs for friends and options available for interventions (Blieszner & Ogletree, 2017; Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2006; Vargheese et al., 2016).

Taken together, these research findings indicate that different friendship-related intervention strategies are needed for different people and segments of late life. Developing interventions that are flexible and take the diversity of expectations and preferences among older adults into account is more likely to be successful than attending only to the practitioner’s perceptions of friendship or assuming a given intervention will be equally successful across all elders.

Enacting and Assessing Interventions

We suggest that gerontological researchers form partnerships with service providers interested in increasing the social connectedness of older adults to plan interventions and appropriate assessment components. Designing research-informed interventions aimed at addressing identified needs could lead to more nuanced, hence more effective, interventions. As shown by research findings described in this article, different groups of older adults would likely benefit from programs targeting specific aspects of friendship structure versus interactive processes and dyadic versus network outcomes. The results of such collaborations could also inform friendship research by increasing knowledge of the antecedents and consequences of friendship patterns and how these change across the life course.

This suggestion also is consonant with Cornwell, Laumann, and Schumm’s (2008) urging increased dialogue between social gerontological and social network researchers. The former researchers tend to have a more applied orientation and to have ties with those in direct contact with older adults, whereas the latter tend to have more appreciation for the complexity of friendships. Perhaps social gerontological researchers could act as bridges between professionals who work with older adults and social network researchers.

Gerontological practitioners are more likely to be interested in collaboration on friendship intervention design and evaluation now than in the past because today the importance of social connectedness for older adults is more widely recognized and the need for interventions is a subject of public dialogue. For example, in the introduction to an issue of the Public Policy & Aging Report, Hudson (2017, p. 121) discussed isolation, loneliness, and a lack of social connection among older adults, noting that “[p]olicymakers, practitioners, and researchers have come to focus attention on this little-recognized and dangerous condition facing so many older people.” In the same issue, Ryerson (2017) described AARP’s Connect2Affect initiative (https://connect2affect.org/), which is facilitating the type of collaboration between researchers and service providers we recommend. This collaborative effort with the Gerontological Society of America, Give an Hour, the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging, and the UnitedHealth Group provides tools and resources designed to assess risk and help isolated older adults become more involved with their communities. The initiatives Ryerson described use technology to improve connectedness—development of a ride-hailing app to increase the use of public transportation, examination of whether the use of hands-free voice-controlled communication devices decreases isolation, and evaluation of the effectiveness of phone outreach in helping retirees feel more connected to others. Although these interventions were designed to increase connectedness in general rather than in friendships per se, it is promising that AARP is facilitating collaboration among service providers and researchers, evaluating the effectiveness of selected interventions, and producing results that could lead to the systematic implementation of programs at the community, state, or national levels.

The clear benefits of social engagement among old people and concern about lack of social connectedness point to the value of and need for continued collaboration among researchers and service providers. The framework for conceptualizing friendship structure, processes, and phases discussed previously and illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 provides guidelines for identifying needs and designing tailored interventions targeted to addressing them. Accumulating evidence that such programs are effective in increasing connections among friends, improving friendship quality, and benefitting older adults’ health and well-being is essential prior to advocating for policies to support systematic implementation of programs across groups of older adults in need of better social integration.

Conclusion

Friendship is a relationship that can last longer over the life course than any other. The majority of adults participate in friendship, even as the end of life draws near. The likelihood of older adults continuing to enjoy and benefit from interactions with friends combined with the potential for social isolation in old age suggests the importance of investigating friendship in creative new ways to advance understanding of friendship structure, processes, and phases along with their implications for health and well-being. In turn, findings from research on friendship can inform strategies for enhancing friendship opportunities and interactions in order to prevent or alleviate loneliness, social isolation, and depression.

As this review of theories relevant to friendship research in old age and available literature on late-life friendship shows, many unanswered questions about the roles of friends in supporting psychological well-being and health of older adults exist. The integrative conceptual framework combined with theory pertinent to social relationships offers guidance for additional work.

Some structural elements of friendship, such as number of friends and frequency of contact, may not require further investigation—at least, in Western cultures, yet relatively less information is available on the effects of other structural features on friendship, such as gender, racial ethnic status, subcultural group, and the contexts in which older adults enact friendship. Likewise, many studies have explored various forms of social support, but much less is understood about other behavioral processes. Data on cognitive processes in late-life friendship are scarce, including how people think about and analyze their friend relationships or how perceptions of friends and friend interactions influence friendship initiation, stability, or loss. Similarly, few studies have examined the influence of emotions on friendship quality and phases. An implicit assumption seems to be that friend relations are positive and beneficial, which is generally true. After all, being friends with a particular person is optional. Nevertheless, evidence shows that older adults can be quite troubled by problems with friends yet do not necessarily wish to terminate the relationship (Adams & Blieszner, 1998; Blieszner & Adams, 1998). We need to know more about any dark sides of friendship.

As shown in the section on interventions, most programs aimed at improving friendship opportunities and outcomes for older adults address behavioral processes useful in the phases of forming new ties and enhancing those that exist, in service of preventing or mitigating loneliness and social isolation. Certainly more programs like those are needed as the population of elders increases around the globe. Nevertheless, it also important for community practitioners to focus on problem-solving in friendships, not just in family relationships, to help elders sustain rewarding friend ties that may entail minor disagreements and annoyances, as well as to provide strategies for dissolving friendships that are not merely uncomfortable, but actually toxic.

Friendship intervention programs must also be assessed for suitability to friendship styles in late adulthood as well as programs’ effectiveness in achieving desired outcomes. To build on the intervention research described previously, we suggest that expanding research on friendship in old age will yield useful data on potential suitability and effectiveness of existing programs and might suggest different approaches to explore. It is difficult to plan better-targeted interventions without knowing more about friendship structure and processes. We need studies on the social and psychological costs of friendship, not just benefits, and on what interferes with friendship enactment and satisfaction, not just what promotes it. We need investigations of similarities and differences in friendship across cultural subgroups both domestically and internationally so interventions can vary by context as needed.

The deeper understanding of friendship in old age will also result from mining the data sets identified in Table 1 and exploring data harmonization techniques to conduct cross-national comparisons. In addition to the countries represented in Table 1, we cited friendship research from Spanish-speaking individuals, participants from Hong Kong, Israel, Italy, and Norway, and residents of rural versus urban communities. The articles by ten Bruggencate and colleagues (2018) and Wrzus and colleagues (2013) included data from multiple countries. Though we might rightly assume that friendship is a universal role found in every country, the literature on friendship in late life lacks a comprehensive global perspective.

Initiating more longitudinal studies to track friendship transitions across stages of adulthood and changes in health would confirm or expand cross-sectional findings. Employing designs that tap perspectives of friend dyads and friend networks and using statistical procedures such as latent growth curve analysis and hierarchical linear modeling would permit identifying reciprocal effects of friends on one another and the reciprocal impact of friend networks on dyads and individuals. The results of all these recommendations would offer important and useful new insights about this crucial relationship in the advanced years of life.

Funding

None reported.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Acknowledgments

R. Blieszner conceived of the manuscript, drafted sections, and integrated sections written by coauthors. A. M. Ogletree conducted an extensive literature review, drafted sections, developed Table 1, and helped to review the manuscript. R. G. Adams contributed to the literature review, drafted the interventions section, and helped to review the manuscript. R. G. Adams and R. Blieszner developed and revised Figures 1 and 2 over the course of their research collaboration. We appreciate the assistance of Koji Ueno in suggesting the concept of cognitive and affective motifs and drafting Figure 2.

References

- aan het Rot M., Moskowitz D. S., & Young S. N (2015). Impulsive behaviour in interpersonal encounters: Associations with quarrelsomeness and agreeableness. British Journal of Psychology (London, England: 1953), 106, 152–161. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel E. K. (1989). The ambiguities of social support: Adult daughters caring for frail elderly parents. Journal of Aging Studies, 33, 211–230. doi: 10.1016/0890-4065(89)90017-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G. (1987). Patterns of network change: A longitudinal study of friendships of elderly women. The Gerontologist, 27, 222–227. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.2.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., & Blieszner R. (1993a, June). Older adult friendship patterns and mental health. Washington, DC: Final report of a study sponsored by the AARP Andrus Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., & Blieszner R. (1993b). Resources for friendship intervention. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 20, 159–175. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., & Blieszner R (1994). An integrative conceptual framework for friendship research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 163–184. doi: 10.1177/0265407594112001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., & Blieszner R (1995). Aging well with friends and family. American Behavioral Scientist, 39, 209–224. doi: 10.1177/0002764295039002008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., & Blieszner R (1998). Structural predictors of problematic friendships in later life. Personal Relationships, 5, 439–447. doi:10.1111/j.1475–6811.1998.tb00181.x [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., Blieszner R., & de Vries B (2000). Definitions of friendship in the third age: Age, gender, and study location effects. Journal of Aging Studies, 14, 117–133. doi: 10.1016/S0890-4065(00)80019-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., Hahmann J., & Blieszner R (2017). Interactive motifs and processes in old age friendship. In Hojjat M. & Moyer A. (Eds.), The psychology of friendship (pp. 39–55). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. G., & Torr R (1998). Factors underlying the structure of older adult friendship networks. Social Networks, 20, 51–61. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(97)00004-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., & Akiyama H (1987). Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. Journal of Gerontology, 42, 519–527. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.5.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., & Akiyama H., (1995). Convoys of social relations: Family and friendships within a life span context. In Blieszner R. & Bedford V. H. (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the family (pp. 355–371). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa Neves B., Fonseca J. R. S., Amaro F., & Pasqualotti A (2018). Social capital and internet use in an age-comparative perspective with a focus on later life. PLoS One, 13, e0192119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béland F., Zunzunegui M. V., Alvarado B., Otero A., & Del Ser T (2005). Trajectories of cognitive decline and social relations. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, P320–P330. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R. (1989). Developmental processes of friendship. In Adams R. G. & Blieszner R. (Eds.), Older adult friendship: Structure and process (pp. 108–126). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R. (1993). Resource exchange in the social networks of elderly women. In Foa U. G., J. Converse K. Y. Jr. Törnblom, & Foa E. B. (Eds.), Resource theory: Explorations and applications (pp. 67–79). San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R. (1995). Friendship processes and well-being in the later years of life: Implications for interventions. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28, 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R., & Adams R. G (1992). Adult friendship. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R., & Adams R. G (1998). Problems with friends in old age. Journal of Aging Studies, 12, 223–238. doi:10.1016/S0890-4065(98)90001–9 [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R., & Ogletree A. M (2017). We get by with a little help from our friends. Generations, 41(2), 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R., & Ogletree A. M (2018). Relationships in middle and late adulthood. In Vangelisti A. L. & Perlman D. (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (2nd ed., pp. 148–160). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]