Description

A woman in her 80s with Alzheimer’s disease presented with dyspnoea and chest pain. The patient had a heart rate of 109, respiratory rate of 24 and was hypoxic, needing 4 L of oxygen supplementation. Blood pressure was at 142/78 which was her baseline. Physical examination showed an anxious patient with pallor and bilateral lower extremity oedema. Initial laboratory workup was significant for a troponin 0.23 (0.00–0.03 ng/mL), B-natriuretic peptide 535 (0–100 pg/mL), creatinine 1.81 (0.60–1.40 mg/dL), blood urea nitrogen 28 (6–23 mg/dL) and lactate 2.4 (0.2–1.8 mmol/L). A ventilation-perfusion scan was performed and showed a high probability of pulmonary embolism (PE) with multiple mismatched perfusion/ventilation defects. Ultrasound doppler was positive for a deep venous thrombosis in the left popliteal vein. The patient was subsequently placed on heparin drip. Initial transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a 1×2 cm mobile echodensity in the right ventricle, suggestive of a right ventricular thrombus (RVT) that appeared to be attached to the ventricular wall or chordae and extended into the right ventricular outflow tract (figures 1 and 2, videos 1–3). Ejection fraction was normal and right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) was elevated at 66 mm Hg. Due to concerns about possible embolisation, the patient was referred to cardiovascular surgery for evaluation for AngioVac suction thrombectomy. But given the location of the thrombus and manipulations that would be required to cross the tricuspid valve with the device, there was a high likelihood that the thrombus would be dislodged during the procedure and may not be retrievable. Medical management was continued as patient remained stable with the resolution of tachypnoea and decreasing oxygen requirements. The following day the patient experienced sudden onset vomiting and respiratory distress with worsening hypoxia. Repeat echocardiogram demonstrated disappearance of previously observed RVT (figure 3, videos 4 and 5), suggesting its migration causing massive PE along with right heart strain with severely elevated RVSP (92.8 mm Hg). An emergent CT angiography of the chest was ordered for anatomical evaluation prior to ultrasound-enhanced thrombolytic therapy but the patient deteriorated with pulseless electrical activity. Advanced cardiac life support protocol was initiated but the patient could not be resuscitated.

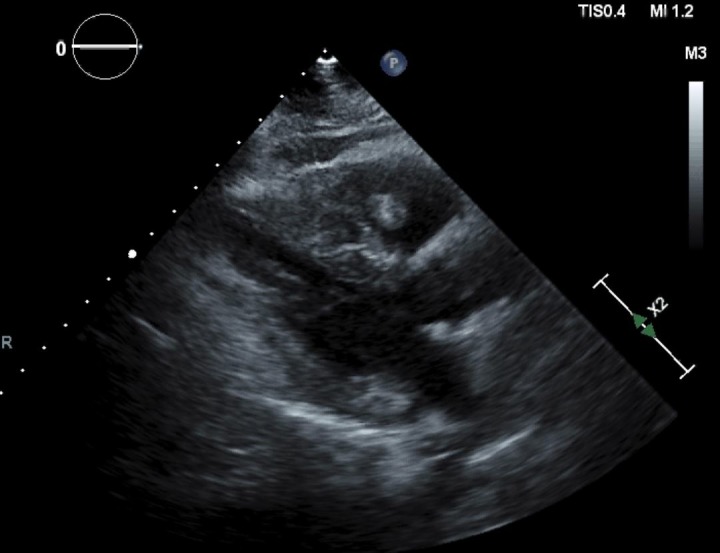

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram parasternal long axis view showing a thrombus in the right ventricular outflow tract.

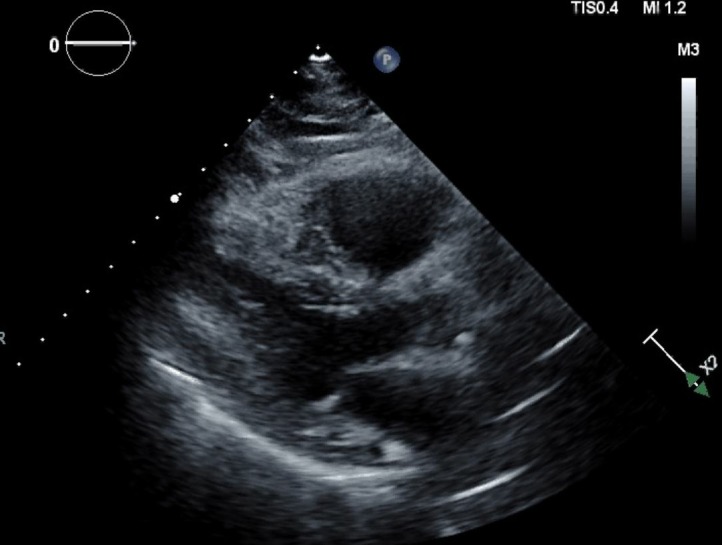

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram right ventricular inflow view showing a thrombus in the right ventricular cavity.

Video 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram parasternal long axis view showing a highly mobile thrombus in the right ventricular outflow tract.

Video 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram right ventricular inflow view showing a highly mobile thrombus in the right ventricular cavity.

Video 3.

Transthoracic echocardiogram parasternal short axis view at the level of the great vessels showing a highly mobile thrombus in the right ventricular cavity.

Figure 3.

Transthoracic echocardiogram parasternal long axis view showing a dilated right ventricle with no visible thrombus.

Video 4.

Transthoracic echocardiogram parasternal long axis view showing a dilated right ventricle with no visible thrombus.

Video 5.

Transthoracic echocardiogram apical four chamber view showing a severely dilated right ventricle with very poor contractility.

RVT has been detected in about 4.5% of patients with PE who underwent echocardiography in a study conducted by Casazza et al 1; the presence of which increases the risk of mortality compared with those with PE alone. Routine use of echocardiogram is not recommended in every patient who presents with PE. In haemodynamically unstable patients with a suspected PE, an echocardiogram can provide an immediate and presumptive diagnosis if a thrombus or an RV strain is visualised. An echocardiogram can also help risk-stratify patients who are at higher risk of mortality. This can guide clinicians in the emergent use of thrombolytic therapy.

Although guidelines exist to stratify and treat PE, the management with co-existence of an RVT is still uncertain. Three types of RVT has been described. Thrombus which are thin, long and extremely mobile and resemble a snake or a worm are type A and is believed to arise from peripheral veins. This type is classified as high-risk and is more associated with severe PE. More immobile thrombi are classified as type B and are thought to originate in situ. PE was noted in about 40% of patients in this subgroup but was never fatal.2 Type C is rare, mobile and has an appearance similar to that of a myxoma.

In patients with an acute PE, haemodynamic instability is the only widely accepted indication for systemic thrombolysis. In patients with contraindication to thrombolysis or with no clinical improvement after its administration, surgical or catheter-directed embolectomy is indicated. Catheter-directed thrombolysis is also an option for patients who fail to improve on systemic thrombolysis. As our patient became haemodynamically stable, systemic thrombolysis was not indicated on presentation. The thrombus detected did not have any of the classic morphology described but the high mobility was more consistent with a type A thrombus. In cases of PE complicated with an RVT, immediate thrombolysis or embolectomy should be considered in the absence of contraindications in patients with a type A thrombus despite haemodynamic stability due to a high likelihood of embolisation and mortality. Large studies are indicated to determine optimal management for these cases. Type B thrombus has a more favourable outcome and thrombolysis is currently not recommended.3

Although our patient clearly demonstrated a visible RVT on TTE, other imaging modalities can also be employed to better characterise the lesion in stable patients. When suboptimal images are reported with TTE, utilisation of contrast is recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography. In addition, the use of contrast-enhanced MRI in some studies suggest that this modality is superior to TTE and transoesophageal echocardiogram for detecting mural thrombi, with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 99%.4 These imaging techniques can provide further information as to whether the intracardiac mass is a thrombus, tumour, or vegetation—all of which may have different therapeutic interventions.

Learning points.

There are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for the treatment of pulmonary embolism (PE) complicated by a right ventricular thrombus.

Type A thrombi are morphologically serpiginous, mobile and are more associated with severe PE. Thrombolysis is indicated in this subgroup in the absence of contraindications.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM and YS created the initial manuscript; CA and SKK revised it.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1.Casazza F, Becattini C, Guglielmelli E, et al. Prognostic significance of free-floating right heart thromboemboli in acute pulmonary embolism: results from the Italian Pulmonary Embolism Registry. Thromb Haemost 2014;111:53–7. 10.1160/TH13-04-0303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronik G. The European Cooperative Study on the clinical significance of right heart thrombi. European Working Group on Echocardiography. Eur Heart J 1989;10:1046–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinesh Kumar US, Nareppa U, Shetty SP, et al. Right ventricular thrombus in case of atrial septal defect with massive pulmonary embolism: a diagnostic dilemma. Ann Card Anaesth 2016;19:173–6. 10.4103/0971-9784.173043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang BK, Platts DG, Javorsky G, et al. Right ventricular thrombus detection and multimodality imaging using contrast echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Heart Lung Circ 2012;21:185–8. 10.1016/j.hlc.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]