Abstract

The award of the 2017 Nobel Prize in chemistry, ‘for developing cryo-electron microscopy for the high-resolution structure determination of biomolecules in solution’, was recognition that this method, and electron microscopy more generally, represent powerful techniques in the scientific armamentarium for atomic level structural assessment. Technical advances in equipment, software, and sample preparation, have allowed for high-resolution structural determination of a range of complex biological machinery such that the position of individual atoms within these mega-structures can be determined. However, not all targets are amenable to attaining such high-resolution structures and some may only be resolved at so-called intermediate resolutions. In these cases, other tools are needed to correctly characterize the domain or subunit orientation and architecture. In this review, we will outline various methods that can provide additional information to help understand the macro-level organization of proteins/biomolecular complexes when high-resolution structural description is not available. In particular, we will discuss the recent development and use of a novel protein purification approach, known as the the PA tag/NZ-1 antibody system, which provides numberous beneficial properties, when used in electron microscopy experimentation.

Keywords: PA tag, NZ-1, Domain mapping, Electron microscopy

Introduction

The 2017 Nobel Prize in chemistry for the development of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) was recognition that electron microscopy (EM) has come of age as a powerful technique for determining the structure of biological macromolecules and protein complexes (Frank 2018). Recent advances in microscope components (McMullan et al. 2016; Danev and Baumeister 2016) have been matched by improvments in analysis software (Zivanov et al. 2018; Grant et al. 2018), and novel sample preparation techniques (Razinkov et al. 2016; Kaledhonkar et al. 2018), which all together have allowed for the high-resolution structural determination of a range of complex biological machinery (Liang et al. 2017; Sugita et al. 2018; Qiu et al. 2018). At high resolutions, the identity of individual residues and atoms can be determined to some degree of certainty and the local and global structure of the target biomolecule can be understood within limits related to responsible interpretation of the experimental data. However, not all targets can be resolved at high-resolution due to various intrinsic or extrinsic properties (that may be intractable for a given experiment), and so in these cases, the identity of side chains, secondary structures, or even whole domains can remain ambiguous, requiring the use of other tools to correctly characterize the domain or subunit orientation and architecture. In this review, we will outline various methods that can provide localization information, sufficient to help understand the macro-level organization of protein and biomolecular complexes, where high-resolution features are not present. In particular, the recent development of a novel protein purification system, the PA tag, has found a number of applications in a range of EM experimental contexts due to the unique structural features it proffers (Fujii et al. 2014, 2016).

Identifying domains at intermediate resolutions

As with any high-resolution structural technique, cryo-EM can facilitate understanding of the relationship between structure and function in the biomolecular complex under investigation (e.g., Fislage et al. 2018). The higher the resolution, the easier it is to determine the correspondence between local and global subunit or domain topology and the function of a target biomolecule. However, if the target can only be determined at an intermediate resolution (considered to be between 10 and 20 Å) due to some combination of extrinsic factors, (technical limitations of the microscope, difficulties with analysis), or intrinsic factors (excessive conformational variation, small size or highly variable complex composition), then other methods will be required to fully determine the target structure. As an example, the order of domains for the small pseudosymmetrical protein LRP6 was not clear from intermediate resolution maps until a comparison was made with two different fragment antibody (Fab) bound structures to the unbound apo form (Matoba et al. 2017). The introduction of ligand (in this case an antibody) provided additional structural features that corresponded to the known binding site, allowing the subunit organization to be understood even at intermediate resolution. Collectively, strategies that leverage some other form of intermediate resolution information (compared with high-resolution features such as the side chains of amino acids) are referred to as EM labeling methods, as often they use an additional label to help identity a domain or subunit by comparing the labeled and unlabeled form and inferring localization information from the additional label density. EM labeling strategies can be classified coarsely as either modification-free methods, that use a non-covalently attached ligand, or alternatively, as modification-based methods, which require the genetic or chemical modification of the target (Table 1). Three important properties of EM labels are their specificity, affinity, and label occupancy. A high specificity ensures that only the target region is labeled, although this can lower the broad applicability of the label system to only targets with a specific epitope. A high affinity allows for extended reactions and preparation of the sample, whereas a low affinity label may dissociate before the sample has been prepared. The occupancy of a label is important as it will mean that lower levels of data are required to capture a particular labeled state. For example, if only 1% of the imaged proteins are labeled then data collection requirements would be 100 times greater than a comparable case were 100% of all particles have a label present. However, in complex systems these requirements are not the sole determinant of success and so any tuning of the specificity, affinity, and occupancy of a label system often needs to be balanced against other experimental requirements.

Table 1.

EM labeling tools showing targetable region, modification size, and type of tag

| Name | Modification | Target site | Modified residues | Tag | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAmSA | No | Transmembrane | 0 | Streptavidin | Perry et al. 2019 |

| Fab | No | Internal | 0 | Various Fab | Wu et al. 2012 |

| Ligands | No | Various | 0 | Various | e.g., Zingsheim et al. 1982 |

| MBP-UAA | Yes | Internal | 1 | MBP | Dambacher and Lander 2015 |

| Deletions | Yes | Internal | Various | – | e.g., Bui et al. 2008 |

| MBP | Yes | Terminal | 396 | MBP | Ciferri et al. 2012 |

| Dynein interaction domain | Yes | Terminal | 84–111 | DID protein | Flemming et al. 2010 |

| Efficient mapping by internal labeling | Yes | Internal | 238 | GFP | Ciferri et al. 2015 |

| eGFP | Yes | Internal | 238 | eGFP | Zang et al. 2016, 2018 |

| Domain Localization by RCT Sampling | Yes | Internal | 15 | Streptavidin | Lau et al. 2012 |

| PA tag | Yes | Internal | 13 | NZ-1 Ab | Brown et al. 2018 |

Modification-free methods

Various ligands can be used as EM labels provided they have a known binding region, sufficient affinity to guarantee their presence in the imaged sample, and importantly, are large enough that they will be visible at the desired resolution of investigation. Compounds ranging from antibodies (Boisset et al. 1993), detergents (Perry et al. 2019), to even venom (Zingsheim et al. 1982) have been used to identify ambiguous domains and subunits. Modification-free EM labeling depends on the availability of an appropriate ligand, but have the advantage that, as there is no genetic modification required, there is a lower risk of destabilizing sensitive complexes that may not handle the introduction of a new domain. A recently developed strategy, known as BAmSA [standing for biotinylated amphipol (BA) and monovalent streptavidin (mSA)], exploits the hydrophobic properties of transmembrane regions to cluster biotinylated amphipol, that subsequently allows for labeling with streptavidin. These regions can then be identified in negative stain images, as well as cryo-EM 2D classes and 3D density maps (Perry et al. 2019). Other useful tools include monoclonal antibodies as they can have a high specificity and affinity (Boisset et al. 1993, 1995; Kelly et al. 2010; Matoba et al. 2017; Cormier et al. 2018). Antibody labeling can be broadly generalized with phage display technologies to develop antibodies for various target regions (Wu et al. 2012); however, there is a potentially higher experimental cost due to the extensive search of epitope-paratope space that is required to identify high-specificity and high-affinity antibodies.

EM labeling through modification of the target complex

If a deletion variant is available which lacks a particular subunit or domain, then this can be used to identify the deletion location by comparison with the wild type complex. This has been used extensively to understand the cross-sectional architecture of the cilia and flagella as there are many variants available that lack single or multiple elements relative to the wild-type (Bui et al. 2008; Heuser et al. 2009, 2012; Pigino et al. 2011). The accuracy of such experiments depends on the structural integrity of the variant being maintained when a subunit or component is missing so that the only difference between the wild-type and the deletion variant is the missing region. In the published cases involving the cilia and flagella, which are large multi-subunit components of the cellular machinery on the order of 1–5 μm, mutations that knock-out a single element are demonstrably stable (e.g., Pigino et al. 2011). However for smaller structures the conformation can be altered by removing a component, meaning that such a strategy may not be effective.

Targeted labeling is also possible by inserting new residues or domains into a complex. Insertions can range in size from single mutations, to small epitopes, up to entire domains. With smaller insertions, additional binding partners are necessary to allow for visualization of the insertion site. Site-directed mutagenesis of a single amino acid to certain specific unnatural amino acids (UAA) can can allow for chemical conjugation to maltose binding protein (MBP), a two domain 40 kDa protein that is visible under EM, providing localization of the targeted mutation (Dambacher and Lander 2015). While this process has the advantage of only requiring a single mutation to introduce an UAA, it does require additional reactions to cause the conjugation of MBP, which could introduce some experimental limitations (e.g., very sensitive complexes that cannot withstand additional reactions). Under these conditions, it may be more advantageous to directly insert a new domain so that it is expressed together with the target, without requiring additional tagging reactions. Again, MBP can be used here by directly inserting the entire protein into the terminal regions of the target complex allowing the localization of this domain (Ciferri et al. 2012; Lander et al. 2012). Provided the insertion site does not interfere with expression of the target molecule, the constitutive expression of a tag such as MBP is useful, as there is essentially 100% effective tagging. One drawback of using MBP is that the insertion site is limited to the terminal regions, and so other tags have been developed that can be targeted to central domains. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) has closely situated terminal regions and so can be inserted directly into surface exposed loops of a target protein, allowing tagging of central domains (Ciferri et al. 2012, 2015; Zang et al. 2016, 2018). While constitutive expression does not require any additional tagging reactions, there is a potential reduction in protein yield as the insertion can interfere with expression or protein folding. This can be compensated for by including additional linker residues between the target and the insertion to allow for flexibility and correct folding; however, this may reduce the resolvability of the inserted tag due to the increased flexibility of the domain (Zang et al. 2018). Insertion of a smaller epitope that can be labeled after expression is a way to overcome this potential limitation. Self-assembling tags that can be built after protein expression could solve this issue, such as the dynein interaction domain (DID), a terminal extension of 84 amino acids which self-assembles after protein expression thereby reducing the potential interference that may come from constitutively expressing a large tag (Flemming et al. 2010). Domain localization by RCT sampling (DOLORS) involves the insertion of the 15 amino acid AviTag, which can be inserted into central loops and then post-translationally biotinylatedand tagged with streptavidin (Lau et al. 2012). For a given experiment, the appropriate label depends on the stability of the target complex, if it is able to accept insertions of whole domains such as GFP, or MBP, or whether smaller insertions are more ideal but with the requirement of additional reactions to effect tagging. As we will discuss in the next section, protein purification systems offer a range of tools potentially suitable for this purpose.

Epitope-based tagging

Epitope-based purification systems and their conjugate antibodies can be used as labels in EM due to their high affinity and specificity. One area that requires some consideration is the placement of the epitope, due to the fact that inserting an epitope directly into a central domain can deform the epitope and render it unrecognizable by its conjugate antibody (Fujii et al. 2016). This limitation has been previously recognized when designing constructs for protein purification, as often only the C-, or N-terminal positions are considered for epitope insertion (Malhotra 2009), or alternatively, the insertion site must be carefully selected inside a long loop region (Dinculescu et al. 2002; Morlacchi et al. 2012) or with additional linker residues (Facey and Kuhn 2003; Kendall and Senogles 2006). In all of these cases, the insertion site is chosen to preserve conformational freedom of the epitope so that it can be recognized by the antibody. While some epitopes which have been used as an EM label (e.g., FLAG tag) have been placed in the terminal region (Kelly et al. 2010), other recently developed systems have a number of properties that allow central insertion. In particular, the PA tag and its conjugate antibody, NZ-1, have a particular degree of freedom for internal insertion (Brown et al. 2018) due to unique structural features of the peptide (Fujii et al. 2016).

PA tag/NZ-1 antibody system

The development and experimental characterization of the PA tag/NZ-1 antibody system is reviewed in detail elsewhere (Brown and Takagi 2018), but in brief, the monoclonal antibody NZ-1 was identified during a search for inhibitors of cancer induced platelet aggregation (Kato et al. 2006), and was shown to block aggregation by binding to a 38–51 amino acid long sequence in the PLAG domain of the type I transmembrane protein podoplanin (Ogasawara et al. 2008). Due to the high affinity of the interaction and the small size of the epitope, it was reasoned that the peptide could make a useful protein purification tool and so the minimum recognition site was identified as the dodecapeptide (GVAMPGAEDDVV), dubbed the PA tag (Fujii et al. 2014). The PA tag and NZ-1 antibody have a number of properties that are attractive as a purification handle, including a very high binding affinity relative to other purification tags (Table 2), mild elution conditions, and a very low dissociation rate that allows for extensive washing for removal of contaminants (Fujii et al. 2014). As a purification tool, the PA tag/NZ-1 system has been used extensively to purify a wide range of proteins (Kitago et al. 2015; Mihara et al. 2016; Suzuki et al. 2016; Umitsu et al. 2016; Meng et al. 2017; Nagae et al. 2018; Tabata et al. 2018).

Table 2.

Size and binding affinities of various purification tools

| Tag name | Residues | KD | kD reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FlAsH | 6 | 1.00E-11 | Wombacher and Cornish 2011 |

| PA tag | 13 | 4.00E-10 | Fujii et al. 2014 |

| G196 | 9 | 1.25E-09 | Tatsumi et al. 2017 |

| HA | 9 | 1.60E-09 | Fujii et al. 2014 |

| MYC | 10 | 2.20E-09 | Fujii et al. 2014 |

| SBP-tag | 38 | 2.50E-09 | Keefe et al. 2001 |

| CBP | 26 | 3.70E-09 | Montigiani et al. 1996 |

| Nanotag15 | 15 | 4.00E-09 | Lamla and Erdmann 2004 |

| AGIA | 9 | 4.90E-09 | Yano et al. 2016 |

| CP5 | 5 | 7.49E-09 | Takeda et al. 2017 |

| TARGET | 21 | 1.00E-08 | Tabata et al. 2010 |

| ABD | 46 | 1.35E-08 | König and Skerra 1998 |

| FLAG | 8 | 2.80E-08 | Fujii et al. 2014 |

| Strep-tag II | 7 | 1.02E-06 | Voss and Skerra 1997 |

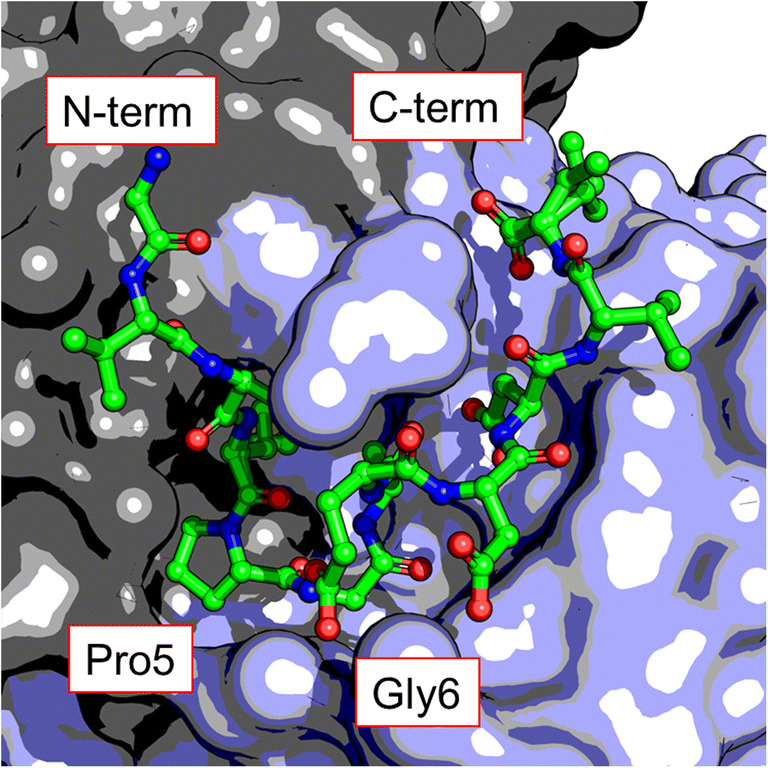

To better understand the structural causes of the high affinity interaction between PA tag and NZ-1 antibody, the crystal structure of the apo and PA peptide-bound NZ-1 Fab (Fig. 1) were collected at 1.65 and 1.70 Å respectively (Fujii et al. 2016). Analysis of these data showed several features that suggest both the antibody and peptide are present in a binding competent conformation prior to interaction that could provide a favorable entropic contribution to binding. First, the structural difference between the apo and peptide-bound NZ-1 was low (~ 0.5 Å RMSD of Cα atoms) indicating that only a minimal conformational change is required upon binding with the PA peptide. Second, several water molecules that form part of the hydrogen bonding network that stabilizes the PA peptide in the binding pocket were also present in the apo structure. Finally, the structure of the PA peptide in the binding pocket of the NZ-1 Fab also offered an explanation for the high affinity interaction and implied some useful applications of the PA tag. The central proline-glycine residues in the peptide cause the formation of a type II β-turn in the NZ-1-binding pocket and the C-, and N-terminals are oriented in the same direction (Fig. 1). The type II β-turn in the PA peptide, its terminal proximity (~ 10 Å) and its orientation, implied that NZ-1 recognizes the PA peptide, not as a linear epitope, but as a compact form that could be inserted into surface exposed loops of central domains without epitope deformation. Such a 'mobile epitope’ would be a useful tool as it has a ready conjugate antibody with high affinity.

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of the PA peptide (GVAMPGAEDDVV) in the binding pocket of NZ-1 Fab (PDB: 4yo0). The proline-glycine positions 5–6 of the peptide cause a type II β-turn that orients the terminal regions in the same direction

To demonstrate the mobile epitope functionality of the PA tag, the cell surface heterodimeric receptor αIIbβ3-integrin was selected as a test case (Fujii et al. 2016) for the reasons that (1) the heterodimer can be easily reconstituted (Takagi et al. 2002), and (2) the αIIb-subunit has an extensive extracellular region with four β-rich domains that contain multiple surface exposed loops where the PA tag could be inserted (Zhu et al. 2008). Ten different constructs were generated by inserting a single PA peptide directly into various surface exposed loops in the αIIb-subunit and 80% of these were successfully expressed. A non-exhaustive search of the literature found that the failure rate for inserting proteins or peptides into internal domains is 40% (Jarvik and Telmer 1998), and so the lower failure rate of the PA peptide was an initial indication that the small peptide generally does not disrupt protein expression and folding. Importantly, all of the PA tag containing constructs that could be expressed maintained reactivity with NZ-1 showing that the direct insertion of the PA peptide did not distort its epitope. In contrast, two common purification tags, FLAG tag (DYKDDDDK) and MYC tag (EQKLISEEDL), that were inserted into the same loop regions lost reactivity with their respective antibodies (M2 and 9E10) providing evidence that internal insertion distorts linear peptides but not the PA peptide. Interestingly, while the crystal structure of the PA peptide and NZ-1 Fab showed a 10.2 Å spacing between the C-, and N-terminals of the peptide some of the chosen insertion sites in the αIIbβ3-integrin had a spacing that was as small as 5.2 Å, suggesting a high degree of flexibility when choosing an insertion site. This interpretation is also supported by the crystal structure, which shows that the terminal regions of the PA peptide are not involved in antibody recognition. Given the mobile nature of the PA peptide and the high affinity of NZ-1, it was reasoned to be suitable for use as a tool for domain labeling in EM experimentation.

Labeling of internal domains using the PA peptide and NZ-1 Fab has been used to identify domains and subunits for a range of proteins (Wang et al. 2018a, b; Brown et al. 2018). The type II β-turn conformation of the peptide allows the insertion of the peptide into central domains to give a mobile EM labeling system. Such a system has other uses, for example if the PA peptide is carefully inserted into a rotary protein such as the V-ATPase, then binding of NZ-1 can be used to lock the complex into a particular conformation (Tsunoda et al. 2018). By locking the conformational state of a protein, previously rare structural states can be increased, allowing their structural determination using cryo-EM. This system has the advantage of (1) being a highly mobile epitope that can be inserted into central domains, (2) having a ready-made high affinity antibody in NZ-1, and (3) requiring a single labeling step that does not need any other reactions.

Conclusion

Despite the technological and analytical advances that have occurred with cryo-EM, there are still many experimental situations in which attainment of atomic resolution is a not realizable proposition. Tools that can be used to identify subunits or domains from intermediate resolution EM structures, or that can alter the conformation of a target in such a way as to reduce conformational variability are still needed. With respect to these situations, a range of methods exists that can be used to provide information about the location and organization of domains and subunits. These include those that can target broad chemical properties of a target system, such as hydrophobic transmembrane regions (Perry et al. 2019), to more specific approaches involving monoclonal antibodies that recognize a single epitope (Wu et al. 2012). Such a range of tools mean that, for a particular experimental situation, the appropriate properties of the labeling approach including, the type of modification, its size, its affinity and the nature of the chemisty used for carrying out the labeling reaction can all be optimized. One such tool, the PA tag/NZ-1 antibody system has been employed for a wide range of uses such as protein purification (Fujii et al. 2014), Western blotting, cell flow cytometry (Fujii et al. 2014), conformational reporting (Fujii et al. 2016), domain level tagging (Wang et al. 2018a, b; Brown et al. 2018), and to influence conformational states of target biomolecules (Tsunoda et al. 2018). We hope that this review has alerted the biophysics community to this toolbox of intermediate resolution level approaches, which can provide extra structural information in EM experimentation when full atomic detail is not attainable for experimental reasons.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Joachim Frank for providing helpful comments on an early draft of this manuscript. This review was funded by National Institute of Health (NIH) R01 GM 29169 (to Joachim Frank) and Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS) funded by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP18am0101075 (to Junichi Takagi).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Zuben P. Brown declares that he has no conflict of interest. Junichi Takagi declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Boisset N, Radermacher M, Grassucci R et al (1993) Three-dimensional immunoelectron microscopy of scorpion hemocyanin labeled with a monoclonal Fab fragment. J Struct Biol 111:234–244. 10.1006/jsbi.1993.1053 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boisset N, Penczek PA, Taveau JC, et al. Three-dimensional reconstruction of Androctonus australis hemocyanin labeled with a monoclonal Fab fragment. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:16–29. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ZP, Takagi J (2018) The PA tag: a versatile peptide tagging system in the era of integrative structural biology. In: Integrative Structural Biology with Hybrid Methods. pp 59–76. 10.1007/978-981-13-2200-6_6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brown ZP, Arimori T, Iwasaki K, Takagi J. Development of a new protein labeling system to map subunits and domains of macromolecular complexes for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2018;201:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui KH, Sakakibara H, Movassagh T, et al. Molecular architecture of inner dynein arms in situ in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii flagella. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:923–932. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciferri C, Lander GC, Maiolica A, et al. Molecular architecture of human polycomb repressive complex 2. Elife. 2012;2012:1–22. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciferri C, Lander GC, Nogales E. Protein domain mapping by internal labeling and single particle electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2015;192:159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier A, Campbell MG, Ito S, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the αvβ8 integrin reveals a mechanism for stabilizing integrin extension. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:698–704. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambacher CM, Lander GC. Site-specific labeling of proteins for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2015;192:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danev R, Baumeister W (2016) Cryo-EM single particle analysis with the Volta phase plate. Elife 5:. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dinculescu A, Hugh McDowell J, Amici SA, et al. Insertional mutagenesis and immunochemical analysis of visual arrestin interaction with rhodopsin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11703–11708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facey SJ, Kuhn A. The sensor protein KdpD inserts into the Escherichia coli membrane independent of the Sec translocase and YidC. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1724–1734. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fislage M, Zhang J, Brown ZP, et al. Cryo-EM shows stages of initial codon selection on the ribosome by aa-tRNA in ternary complex with GTP and the GTPase-deficient EF-TuH84A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:5861–5874. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming D, Thierbach K, Stelter P, et al. Precise mapping of subunits in multiprotein complexes by a versatile electron microscopy label. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:775–778. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J (2018) Single-particle reconstruction of biological molecules-story in a sample (Nobel Lecture). Angew Chem Int Ed 57(34):10826–10841. 10.1002/anie.201802770 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fujii Y, Kaneko M, Neyazaki M, et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif. 2014;95:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Matsunaga Y, Arimori T, et al. Tailored placement of a turn-forming PA tag into the structured domain of a protein to probe its conformational state. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:1512–1522. doi: 10.1242/jcs.176685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant T, Rohou A, Grigorieff N (2018) cisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. Elife 7. 10.7554/eLife.35383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heuser T, Raytchev M, Krell J, et al. The dynein regulatory complex is the nexin link and a major regulatory node in cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:921–933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser T, Barber CF, Lin J, et al. Cryoelectron tomography reveals doublet-specific structures and unique interactions in the I1 dynein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:E2067–E2076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120690109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik JW, Telmer CA. Epitope tagging. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:601–618. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaledhonkar S, Fu Z, White H, Frank J (2018) Time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy using a microfluidic chip. In: Protein Complex Assembly. pp 59–71 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kato Y, Kaneko MK, Kuno A, et al. Inhibition of tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation using a novel anti-podoplanin antibody reacting with its platelet-aggregation-stimulating domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:1301–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe AD, Wilson DS, Seelig B, Szostak JW. One-step purification of recombinant proteins using a nanomolar-affinity streptavidin-binding peptide, the SBP-Tag. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;23:440–446. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DF, Lake RJ, Middelkoop TC, et al. Molecular structure and dimeric organization of the notch extracellular domain as revealed by electron microscopy. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Kendall RT, Senogles SE. Investigation of the alternatively spliced insert region of the D 2L dopamine receptor by epitope substitution. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitago Y, Nagae M, Nakata Z, et al. Structural basis for amyloidogenic peptide recognition by sorLA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:199–206. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König T, Skerra A. Use of an albumin-binding domain for the selective immobilisation of recombinant capture antibody fragments on ELISA plates. J Immunol Methods. 1998;218:73–83. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamla T, Erdmann VA. The Nano-tag, a streptavidin-binding peptide for the purification and detection of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;33:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander GC, Estrin E, Matyskiela ME, et al. Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature. 2012;482:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau PW, Potter CS, Carragher B, MacRae IJ. DOLORS: versatile strategy for internal labeling and domain localization in electron microscopy. Structure. 2012;20:1995–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y-L, Khoshouei M, Radjainia M, et al. Phase-plate cryo-EM structure of a class B GPCR–G-protein complex. Nature. 2017;546:118–123. doi: 10.1038/nature22327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A (2009) Chapter 16 Tagging for protein expression. In: Methods in Enzymology. pp 239–258 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matoba K, Mihara E, Tamura-Kawakami K, et al. Conformational freedom of the LRP6 ectodomain is regulated by N-glycosylation and the binding of the Wnt antagonist Dkk1. Cell Rep. 2017;18:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan G, Faruqi AR, Henderson R (2016) Direct electron detectors. In: Methods in Enzymology. pp 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meng H, Yamashita C, Shiba-Fukushima K, et al. Loss of Parkinson’s disease-associated protein CHCHD2 affects mitochondrial crista structure and destabilizes cytochrome c. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15500. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara E, Hirai H, Yamamoto H, et al (2016) Active and water-soluble form of lipidated Wnt protein is maintained by a serum glycoprotein afamin/α-albumin. Elife 5:. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Montigiani S, Neri G, Neri P, Neri D. Alanine substitutions in calmodulin-binding peptides result in unexpected affinity enhancement. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:6–13. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlacchi S, Sciandra F, Bigotti M, et al. Insertion of a myc-tag within α-dystroglycan domains improves its biochemical and microscopic detection. BMC Biochem. 2012;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagae M, Kizuka Y, Mihara E, et al (2018) Structure and mechanism of cancer-associated N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-V. Nat Commun 9:. doi: 10.1016/j.tcs.2012.03.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara S, Kaneko MK, Price JE, Kato Y. Characterization of anti-podoplanin monoclonal antibodies: critical epitopes for neutralizing the interaction between podoplanin and CLEC-2. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2008;27:259–267. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2008.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry TN, Souabni H, Rapisarda C, et al. BAmSA: visualising transmembrane regions in protein complexes using biotinylated amphipols and electron microscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2019;1861:466–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigino G, Bui KH, Maheshwari A, et al. Cryoelectron tomography of radial spokes in cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:673–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Fu Z, Xu GG, et al. Structure and activity of lipid bilayer within a membrane-protein transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:201812526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812526115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razinkov I, Dandey VP, Wei H, et al. A new method for vitrifying samples for cryoEM. J Struct Biol. 2016;195:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y, Matsunami H, Kawaoka Y, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the Ebola virus nucleoprotein–RNA complex at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature. 2018;563:137–140. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Tsunoda H, Omiya R, et al. Structure of the plexin ectodomain bound by semaphorin-mimicking antibodies. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata S, Nampo M, Mihara E, et al. A rapid screening method for cell lines producing singly-tagged recombinant proteins using the “TARGET tag” system. J Proteome. 2010;73:1777–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata S, Kitago Y, Fujii Y, et al. An anti-peptide monoclonal antibody recognizing the tobacco etch virus protease-cleavage sequence and its application to a tandem tagging system. Protein Expr Purif. 2018;147:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, T a S. Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell. 2002;110:599–511. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda H, Zhou W, Kido K, et al. CP5 system, for simple and highly efficient protein purification with a C-terminal designed mini tag. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K, Sakashita G, Nariai Y, et al. G196 epitope tag system: a novel monoclonal antibody, G196, recognizes the small, soluble peptide DLVPR with high affinity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43480. doi: 10.1038/srep43480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda J, Song C, Imai FL, et al. Off-axis rotor in Enterococcus hirae V-ATPase visualized by Zernike phase plate single-particle cryo-electron microscopy. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15632. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33977-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umitsu M, Sakai K, Ogasawara S, et al. Probing conformational and functional states of human hepatocyte growth factor by a panel of monoclonal antibodies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33149. doi: 10.1038/srep33149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss S, Skerra A. Mutagenesis of a flexible loop in streptavidin leads to higher affinity for the Strep-tag II peptide and improved performance in recombinant protein purification. Protein Eng Des Sel. 1997;10:975–982. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.8.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Han W, Takagi J, Cong Y. Yeast inner-subunit PA–NZ-1 labeling strategy for accurate subunit identification in a macromolecular complex through Cryo-EM analysis. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:1417–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ding Z, Liu X, et al. Architecture and subunit arrangement of the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae COMPASS complex. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17405. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35609-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wombacher R, Cornish VW. Chemical tags: applications in live cell fluorescence imaging. J Biophotonics. 2011;4:391–402. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Avila-Sakar A, Kim J, et al. Fabs enable single particle cryoEM studies of small proteins. Structure. 2012;20:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano T, Takeda H, Uematsu A, et al. AGIA tag system based on a high affinity rabbit monoclonal antibody against human dopamine receptor D1 for protein analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang Y, Jin M, Wang H, et al. Staggered ATP binding mechanism of eukaryotic chaperonin TRiC (CCT) revealed through high-resolution cryo-EM. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang Y, Wang H, Cui Z, et al. Development of a yeast internal-subunit eGFP labeling strategy and its application in subunit identification in eukaryotic group II chaperonin TRiC/CCT. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18962-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Luo BH, Xiao T, et al. Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol Cell. 2008;32:849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingsheim HP, Barrantes FJ, Frank J, et al. Direct structural localization of two toxin-recognition sites on an ACh receptor protein. Nature. 1982;299:81–84. doi: 10.1038/299081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivanov J, Nakane T, Forsberg BO, et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife. 2018;7:1–40. doi: 10.7554/eLife.42166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]