Abstract

Background

Dirofilariasis is an endemic disease in tropical and subtropical countries caused by about 40 different species of dirofilari. Dirofilariasis of the oral cavity is extremely rare and is usually seen as mucosal or submucosal nodules. We also present a case of dirofilariasis of the mandibular third molar region submucosally in a 26 year old male patient.

Purpose

To identify, enlist and analyze the cases of dirofilariasis in maxillofacial region reported worldwide so as to understand the clinical presentation and encourage the consideration of helminthic infections as a possible differential diagnosis in maxillofacial swellings.

Methods

Two authors KC and SK independently searched the electronic database of PUBMED, OVID, Google Scholar and manual search from other sources. A general search strategy was planned and anatomic areas of interest identified. The search was made within a bracket of 1 month by the independent authors KC and SK who assessed titles, abstracts and full texts of articles based on the decided keywords. The final selection of articles was screened for the cases that were reported in the maxillofacial region including the age, gender, site of occurrence and region of the world reported in. A geographic distribution of the reported cases was tabulated.

Results

A total number of 265, 97, 1327, 3 articles were identified by PubMed, Ovid, GoogleScholar and manual search respectively. The final articles were manually searched for duplicates and filtered according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria which led to a final list of 58 unique articles that were included in the study. In total 99 cases were identified.

Conclusion

Although intraoral dirofilarial infections are extremely uncommon, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an intraoral or facial swelling that does not completely respond to routine therapy especially in patients from endemic areas.

Keywords: Dirofilariasis, Maxillofacial, Parasitosis, Diro, Filariasis

Introduction

Dirofilariasis is an endemic disease in tropical and subtropical countries caused by about 40 different species of Dirofilaria [1]. Dirofilaria is primarily confined to animals such as dogs, cats, foxes, raccoons and other wild animals which act as their definitive hosts. Humans are accidental or dead-end host and are infected by less than six species of Dirofilaria that too most commonly by Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis [2].

Dirofilaria infection in humans characteristically manifests as a strong inflammatory reaction in the surrounding tissues and may have a varied clinical presentation depending on the site of infestation. Dirofilariasis of the oral cavity is extremely rare and is usually seen as mucosal or submucosal nodules. We present a case of dirofilariasis of the mandibular third molar region submucosally in a 26-year-old male patient.

Case Report

A 26-year-old male patient reported with a complaint of recurrent episodes of pain and swelling over the right side of lower face to the Department of Dentistry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan. Patient had three episodes of pain and swelling over the duration of 6 months. Extra orally, diffuse swelling of the right cheek was noted without any paresthesia. No cervical or generalized lymphadenopathy was present. Intraorally, pericoronitis and pus discharge around impacted right lower third molar were found (Fig. 1). An orthopantomograph revealed a distoangular impacted mandibular third molar with a small cystic radiolucency around the tooth (Fig. 2). Considering pericoronitis, surgical removal of third molar was planned under local anesthesia and antibiotics. During mucoperiosteal flap reflection, complete loss of periosteum with significant induration of the flap and slight erosion of underlying bone was seen. Suspecting some abnormal mass, procedure was deferred, an incisional biopsy was performed and specimen was sent for histopathological examination. Microscopic examination revealed edematous and inflamed granulation tissue with a profile of a single coiled unsheathed nematode within fibrocartilaginous tissue suggestive of Dirofilaria (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Intraoral view

Fig. 2.

OPG view showing bone erosion distal to 48

Fig. 3.

Histopathological report showing profile of a single coiled unsheathed nematode within fibrocartilaginous tissue

Patient’s chest X-ray ruled out any “coin lesions,” which characterize the lymphatic spread to lungs. Blood investigations revealed slightly raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate without any eosinophilia. Under antibiotic coverage, surgical removal of impacted right third molar along with excision of remaining inflamed granulation tissue around third molar was done. Antihelminthic drugs diethylcarbamazine (DEC) 100 mg thrice a day for three weeks, albendazole 400 mg once a day for 1 week and single dose of tablet ivermectin 12.5 mg were prescribed. Patient is on a regular follow-up since 36 months and is completely asymptomatic.

Aim

To identify, enlist and analyze the cases of dirofilariasis in maxillofacial region reported worldwide so as to understand the clinical presentation and encourage the consideration of helminthic infections as a possible differential diagnosis in maxillofacial swellings.

Materials and Methods

Two authors KC and SK independently searched the electronic database of PUBMED, OVID, Google Scholar and manual search from other sources. A general search strategy was planned, and anatomic areas of interest identified. There was no time bracket limitation for the search. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were identified as follows:

Inclusion Criteria

Cases diagnosed histopathologically or serologically as Dirofilaria

Cases in maxillofacial region in human beings only

Details of case available

English language/translated articles only

Exclusion criteria

Nematodes other than Dirofilaria

Non-human cases

Non-English language/translated articles only

Sites other than maxillofacial region or site details not available

The search was made within a bracket of 1 month by the independent authors KC and SK who assessed titles, abstracts and full texts of articles based on the following keywords: maxilla, mandible, jaw, zygomatic, zygoma, zygomaticotemporal, zygomatico-temporal, palate, palatal, subcutaneous, submucosal, dermal, face, facial, maxillofacial, oral cavity, mouth, cheek, buccal mucosa, buccinators, tongue, medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid, pterygoid, masseter, temporalis, gum, gingiva, lip, parotid, submandibular, lingual, sublingual, nasolabial, labial, infraorbital with Dirofilaria, diro, dirofilariasis, helminth, nematode, and humans.

Titles that did not get excluded based on the exclusion criteria were selected for assessment of abstract or full text. Any disagreement was discussed on, and final selection made based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In addition, references of review articles were used as a retrospective database for articles which were manually handsearched.

The final selection of articles was screened for the cases that were reported in the maxillofacial region including the age, gender, site of occurrence and region of the world reported in. A geographic distribution of the reported cases was tabulated (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7).

Fig. 4.

The world distribution of maxillo-mandibular dirofilariasis

Fig. 5.

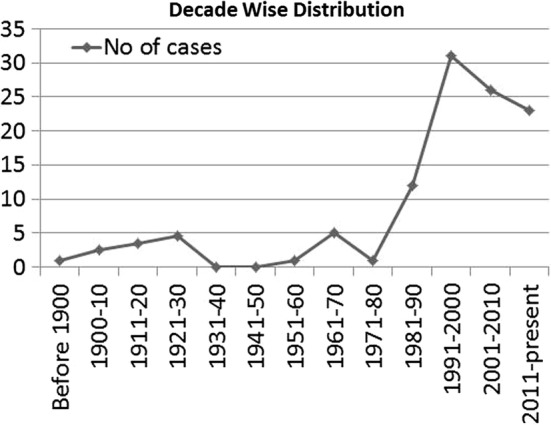

Year wise distribution

Fig. 6.

Age affected

Fig. 7.

Site distribution

Results

Paper Selection

A total number of 265, 97, 1327 and 3 articles were identified by PubMed, Ovid, Google Scholar and manual search, respectively. The final articles were manually searched for duplicates and filtered according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria which led to a final list of 58 unique articles that were included in the study (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Prisma diagram

Details

We checked the references of these articles for other cases and thoroughly studied them. Non-English literature has not been included in our review. Reviews by Avdiukhina et al. [3] and Ilyasov et al. [4] helped us to include cases published in Russian language journals in our review. We could incorporate articles published in French to our review, consulting reviews by Pampiglione [5, 6]. The last search was carried out on January 30, 2018.

In total, we found 99 cases of Dirofilaria affecting the maxillo-mandibular region in literature and the present case is the 100th one.

Results and Discussion

The habitual hosts are infected after a bite by various arthropods which are biological carriers and serve as intermediate hosts and can transmit it to humans during their subsequent meals [7]. In India, dog population is estimated to be around 25 million [8] An Indian study from Southern India reported blood smear from 7.59% of dogs to be positive for Dirofilaria [9]. In another survey, 16.7% of dogs in Mumbai were shown to be infected with Dirofilaria repens and 4.5% of dogs in Delhi were infected with Dirofilaria immitis [10]. This suggests that humans are at a higher risk of acquiring Dirofilaria infection from dogs.

Humans are the dead-end host where Dirofilaria develops into an unmated worm that neither reproduces nor releases microfilariae. Human-to-human and human-to-arthropod transmission, thus does not occur [7]. Dirofilaria reaches human through an insect bite that mostly cannot be recalled by patient and sometimes bite may be recalled as painful followed by slight local acute phlogosis (erythema, swelling and pruritis) lasting for few days. Dirofilaria may even invade the blood stream and may be carried to distant sites like lungs, genitalia, omentum. Finally, Dirofilaria dies and mounts a severe foreign body response and forms nodules which may even suppurate, and the signs and symptoms are in accordance with the site of entrapment.

The first reported case of dirofilariasis was in subconjunctival region in France in a 3-year-old female in 1566. Since then more than 800 cases have been reported, and dirofilariasis is considered as an emerging zoonosis [11, 12]. In this review, we analyzed only the cases of dirofilariasis involving the maxillo-mandibular region and characterized them with regard to geographic, age, gender and affected site distribution. The first reported case of maxillo-mandibular dirofilariasis was in year 1864 in a 20-year-old male patient affecting the lip [13]. There are total 100 reported cases of maxillo-mandibular dirofilariasis till now including the present case. (Table 1). There were barely a few reported cases of maxillo-mandibular dirofilariasis before 1980. After that, there was a sharp increase in the reported cases over the next two decades followed by gradual fall over the next two decades. The maximum number of reported cases was in the time frame of 1991–2000 (31 cases) (Fig. 5). The reason for initial increase in all probability is multifactorial. At least a part of increase in the incidence of the disease may be attributed to the changing climatic conditions (temperature, relative humidity, rainfall and evaporation) that favor the growth of the carrier culicidae and also the development of larval phase of nematode inside the carrier [14, 15]. Further, it has been postulated that greenhouse effect has further increased the vector population globally causing an increase in vector-borne diseases like malaria, dengue, and dirofilariasis [16].

Table 1.

Area wise distribution

| S.NO | Reporting Author/ Ref | Year | Age/Sex | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | ||||

| 1 | Senthilvel [17] | 1999 | 39/F | Lip |

| 2 | Padmaja [18] | 2005 | 35/F | Lip |

| 3 | Khurana [19] | 2010 | 45/M | cheek |

| 4 | Joseph [20] | 2010 | 10/F | Nasolabial |

| 5 | Joseph [20] | 2010 | 39/F | Parotid |

| 6 | Joseph [20] | 2010 | 24/F | Infraorbital |

| 7 | Joseph [20] | 2010 | 45/F | Cheek |

| 8 | Permi [21] | 2011 | 40/M | Cheek |

| 9 | Souza [22] | 2013 | 28/M | Cheek |

| 10 | Nath [23] | 2013 | 30/M | Cheek |

| 11 | Kurup [1] | 2013 | 54/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 12 | Khyriem [24] | 2013 | 27/F | Cheek |

| 13 | Manuel [25] | 2014 | 32/M | Buccal vestibule |

| 14 | Janardhanan [26] | 2014 | 54/F | cheek |

| 15 | Premakumar [27] | 2014 | 32/M | Cheek |

| 16 | Krishna [28] | 2015 | 64/F | Infraorbital |

| 17 | Desai [29] | 2015 | 32/M | Buccal mucosa |

| 18 | Balaji [30] | 2016 | 19/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 19 | Present case | 2017 | 26/M | Retromolar area |

| Sri Lanka | ||||

| 20 | Attygalle [31] | 1966 | 48/M | Parotid region |

| 21 | Dissanaike [32] | 1997 | 3/M | Cheek |

| 22 | Dissanaike [32] | 1997 | 10 m/F | Cheek |

| 23 | Dissanaike [32] | 1997 | 28/M | Cheek |

| 24 | Ratnatunga [33] | 1999 | 65/F | Cheek |

| 25 | Ratnatunga [33] | 1999 | 45/M | Cheek |

| 26 | Pitakotuwage [34] | 1999 | 80/F | Cheek |

| 27 | Tilakaratne [35] | 2003 | 26/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 28 | Tilakaratne [35] | 2003 | 80/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 29 | Tilakaratne [35] | 2003 | 52/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 30 | Tilakaratne [35] | 2003 | 28/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 31 | Tilakaratne [35] | 2003 | 4/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 32 | Tilakaratne [35] | 2003 | 40/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 33 | Tilakaratne [35] | 2003 | 53/M | Lip |

| 34 | Jayasinghe [36] | 2011 | 57/F | Cheek |

| 35 | Jayasinghe [36] | 2011 | 20/M | Cheek |

| 36 | Senanayke [37] | 2013 | 11 M/NS | Cheek |

| Italy | ||||

| 37 | Pane [13] | 1864 | 20/M | Lip |

| 38 | Babudiere [5] | 1937 | 18/M | Cheek |

| 39 | Colla [5] | 1967 | 71/M | Cheek |

| 40 | Colla [5] | 1967 | 54/F | Cheek |

| 41 | Bianchi [5] | 1968 | 20/M | Zygomatic |

| 42 | Fruttaldo [5] | 1985 | 40/M | Zygomatic |

| 43 | Fruttaldo [5] | 1985 | 44/M | Zygomatic |

| 44 | Toniolo [5] | 1987 | 23/M | Jaw |

| 45 | Bertiato [5] | 1987 | 25/M | Mandibular |

| 46 | Pampiglione [5] | 1988 | 37/F | Cheek |

| 47 | Pampiglione [38] | 1993 | 53/M | lip |

| 48 | Maccioni [5] | 1994 | 38/M | Zygomatic |

| 49 | Pampiglione [6] | 1996 | 38/M | Zygomatic |

| 50 | Pampiglione [39] | 1996 | 43/F | Temporalis |

| 51 | Cancirini [40] | 1998 | 59/M | Submandibular lymph node |

| 52 | Pampiglione [6] | 1999 | 39/M | Zygomatic |

| 53 | Pampiglione [6] | 1999 | 27/F | Cheek |

| 54 | Pampiglione [6] | 1999 | 4/M | Cheek |

| Russia | ||||

| 55 | Maximova [41] | 1991 | 41/F | Zygomatic |

| 56 | Avdiukhina [3] | 1993 | 35/M | Submandibular |

| 57 | Postnova [42] | 1997 | 33/F | Cheek |

| 58 | Postnova [42] | 1997 | 31/M | Cheek |

| 59 | Postnova [42] | 1997 | 18/F | Cheek |

| 60 | Postnova [42] | 1997 | 35/F | Soft palate |

| 61 | Avdiukhina [3] | 1997 | 55/F | Lip |

| 62 | Laura [43] | 2007 | 23/F | Oral cavity |

| 63 | Laura [43] | 2007 | 43/F | Cheek |

| 64 | Ilyasov [4] | 2014 | 32/F | Cheek |

| 65 | Ilyasov [4] | 2014 | 38/F | Zygomatic |

| 66 | Ilyasov [4] | 2014 | 30/F | Parotid |

| Greece | ||||

| 67 | Triantafillopoulos [44] | 1952 | 26/F | Cheek |

| 68 | Markopoulos [45] | 1990 | 48/F | Cheek |

| 69 | Auer [46] | 1997 | NS | Parotid |

| 70 | Tzanetou [47] | 2009 | 45/F | Cheek |

| France | ||||

| 71 | Quilici [5] | 1982 | 35/F | Zygomatic |

| 72 | Quicili [5] | 1983 | 19/M | Cheek |

| 73 | Lapierre [48] | 1982 | 42/M | Cheek |

| 74 | Quicili [5] | 1986 | 50/M | Zygomatic |

| 75 | Quicili [5] | 1987 | 47/M | Cheek |

| 76 | Quicili [5] | 1991 | 38/F | Zygomatic |

| 77 | Quicili [5] | 1993 | 29/M | Cheek |

| 78 | Quicili [5] | 1993 | 56/M | Cheek |

| 79 | Weill [6] | 1999 | 66/M | Cheek |

| 80 | AbouBacar [49] | 2007 | 35/M | Cheek |

| 81 | Rivière [50] | 2014 | 52/F | Intramasseteric |

| Turkey | ||||

| 82 | Latifoğlu [2] | 2002 | 62/M | Premasseteric mass |

| China | ||||

| 83 | Tsang [51] | 2003 | 42/F | Buccal mucosa |

| Britain | ||||

| 84 | Seddon [52] | 1992 | 12/M | Parotid |

| 85 | Ahmed [53] | 2010 | 32/M | Parotid |

| Tunisia | ||||

| 86 | Kaouech [54] | 2010 | 40/F | Lip |

| Germany | ||||

| 87 | Friedrich [55] | 2014 | 40/F | Zygomaticotemporal |

| Brazil | ||||

| 88 | Pereira [56] | 2015 | 65/F | Buccal mucosa |

| 89 | Daroit [57] | 2016 | 65/F | Buccal mucosa |

| United States of America | ||||

| 90 | Collins BM [58] | 1992 | 53/M | Cheek |

| 91 | AJ Herzberg [59] | 1995 | 66/M | Cheek |

| 92 | Akst LM [60] | 2004 | 73/F | Cheek |

| 93 | VélezPérez [61] | 2016 | 79/M | Buccal mucosa |

| Iran | ||||

| 94 | Maraghi [62] | 2006 | 34/M | Cheek |

| 95 | Radmanesh [63] | 2006 | 31/M | Nasolabial |

| Austria | ||||

| 96 | Fuehrer [64] | 2000 | 59/M | Cheek |

| 97 | Fuehrer [64] | 2008 | 62/F | Cheek |

| 98 | Barbara Bockie [65] | 2009 | 52/M | Cheek |

| Ukraine | ||||

| 99 | Enghelestein [66] | 1973 | 17/F | Submandibular |

| Georgia | ||||

| 100 | Zenaishvili [5] | 1983 | 28/F | Tongue |

Clinical diagnosis of dirofilariasis is almost wrong and is usually mistaken for malignancy, cyst, adenoma, hematoma, lipoma, abscess and a wide range of differentials except dirofilariasis. Jelink et al. [67] reported two patients feeling “worm under skin” who were wrongly admitted in psychiatry ward and were later on diagnosed with Dirofilaria. Similarly, one patient was diagnosed with trigeminal neuralgia and was completely relieved after nematode was removed from the bulbar conjunctiva, and it was probably due to Dirofilaria migration to the head [3].

Radical surgeries were thus performed and later on histopathologically diagnosed it to be Dirofilaria. This has led to an increased interest among academicians resulting in greater reporting, hence further increasing the total evidence in the form of published data. Thus, the increase may have been an indirect result of increased awareness among medical practitioners about Dirofilaria. Technical advancements and increased availability of refined diagnostic aids like use of PAS and Masson–Goldner’s trichrome stains and use of biomolecular techniques like PCR assay for phylogenetic analysis further increased the case detection [68]. Thereafter, gradual decrease in reported cases over the last two decades (26 cases in 2001–2010 and 23 in the present decade) could have been due to better vector control.

Previous reviews of dirofilariasis of whole body have shown it to be an endemic disease of primarily third world temperate countries like Italy, France, Russia and Sri Lanka. In the present review also, this holds true as we have found 62 cases in temperate region and 38 cases in tropical countries. Interestingly the number of cases in the tropical countries is increasing significantly over the last 40 years. On the other hand, reported number of cases in temperate countries is showing a sharp downward trend for the last 3 decades. This virtual shift could also be related partly to control of canine vector-borne diseases in European countries (temperate climate). WHO in 2015 has declared Europe malaria-free with one of its modalities being mosquito control [69]. This vector control could have resulted in decline in cases in last two decades in European countries where earlier it was quite rampant. However europe being declared as malaria free due to vector control and its exact influence on incidence of dirofilaria in europe, still needs to be studied better. Our study reflects that India (19%) has topped the list followed by Italy (18%) and Sri Lanka (17%) in the reported number of cases which could be credited to wide range of climatic conditions, huge population density, large rural population, lack of personal hygiene, reduced availability of preventive health-care facilities, abundance of stray animals and vectors, reduced education, awareness among masses and reduced veterinary facilities.

Age distribution of dirofilariasis shows that it can affect any age group. In our review of 100 patients with maxillo-mandibular dirofilariasis, mean age of occurrence is found to be 39.22 years, with a range from 10 months to 80 years. Maximum number of cases has been reported in the fourth decade of life followed by the third decade (Fig. 6). Female preponderance (51%) has been observed in the present review.

In the review published by Pampiglione et al. [6], only 3.4% of total body cases were from the maxillo-mandibular region. Involvement of maxillo-mandibular region is less common with involvement of the oral cavity being even rarer. In the present review, maximum number of cases were reported in cheek (45%) followed by buccal mucosa (13%) and then zygomaticotemporal region (12%). It seems that as these are the most prominent areas on the face for mosquito bite, Dirofilaria gets inoculated here, migrates and localizes in deeper tissues.

For the diagnosis of dirofilariasis, a suggestive patient history and clinical examination are important clues. Microscopic examination of the removed parasites or their fragments remains the golden standard to confirm the diagnosis. It becomes increasingly difficult for histopathologists to correctly diagnose the nematode when it is in the advanced stage of decomposition [70].

The definitive treatment of Dirofilaria infection in humans is surgical removal of the adult worm. If difficulty is encountered in surgical removal of the worm because of the excessive movement, a cryoprobe can be used for immobilizing it as described by Geldelman [71]. Medication such as diethylcarbamazine (DEC), ivermectin and albendazole is routinely administered. DEC (2 to 4 mg/kg body weight over a period of 4 weeks) is highly specific for microfilaria as it alters its membrane so that they are easily phagocytized by tissue-fixed monocytes. Albendazole is of adjuvant value in treating filariasis [72]. Ivermectin, a broad spectrum antiparasitic drug, blocks the transmission of microfilariae and can be administered as a single oral dose annually without any side effects [73].

Effective way of control of this parasitosis is basically adoption of proper vector control and increasing patient awareness. However, administrating prophylactic dose of ivermectin (> 6 µg/kg once a month for 7 consecutive months) to the canines in the endemic areas has also been proposed [73].

Conclusion

Although intraoral Dirofilaria infections are extremely uncommon, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an intraoral or facial swelling that does not completely respond to routine therapy especially in patients from endemic areas. This study was aimed toward an extensive data analysis of incidence, age distribution and country distribution of dirofilariasis in the world, so as to allow for a better understanding of pattern of maxillofacial dirofilariasis. In our opinion, there has not been much literature study in regard to maxillofacial dirofilariasis exclusively, making it a less likely candidate in differential diagnosis. The study aims to increase awareness of this amid medical professionals. Medical awareness of the risk of the infection is essential, and very often, a detailed history (including travel) is helpful in diagnosis. Many of them remain undiagnosed or unreported. Hence, it is emphasized that surgeon should have an increased awareness about this infection. This study could also serve to draw attention toward organized programs for elimination of the zoonotic disease from dogs and other reservoir hosts.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Kirti Chaudhry, Email: chaudhry_kirti@yahoo.com.

Shruti Khatana, Phone: +91-7357552232, Phone: +91-7411165801, Email: shru.k85@gmail.com.

Naveen Dutt, Email: kirti_chaudhry@gmail.com.

Yogesh Mittal, Email: dryogesh82@gmail.com.

Shailja Sharma, Email: shailjachambial@yahoo.com.

Poonam Elhence, Email: drpoonamelhence@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kurup S, Veeraraghavan R. Filariasis of the buccal mucosa: a diagnostic dilemma. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:254–256. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.114883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latifoglu O, Zmen S, Sezer C. Dirofilaria repenspresenting as a premasseteric nodule. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:217–220. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.125275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avdiukhina TI, Supriaga VG. Dirofilariasis in the Community of Independent States countries: analysis of cases from 1915 to 1996. MedskParazitol. 1997;4:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ilyasov B, et al. Thirty cases of human subcutaneous dirofilariasis reported in Rostov-onDon (Southwestern Russian Federation) Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2015;33:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pampigilone S, CanestriTrotti G. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens: a review of world literature. Parassitologia. 1995;37:149–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pampiglione S, Rivasi F. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens: an update of world literature from 1995 to 2000. Parassitologia. 2000;42:231–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orihel TC. Dirofilariacorynodes(VonLinstow, 1899): morphology and life history. J Parasitol. 1969;55:94–103. doi: 10.2307/3277355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Megat, et al. Canine vector-borne diseases in India: a review of the literature and identification of existing knowledge gaps. Parasites Vectors. 2010;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabu L, Devada K, Subramanian H. Dirofilariosis in dogs and humans in Kerala. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:691–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Megat Abd Rani PA, Irwin PJ, Gatne M, et al. A survey of canine filarial diseases of veterinary and public health significance in India. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:30. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munro A, et al. Human dirofilariasis in the European Union. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:386–389. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(99)01496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadgir S, et al. Sunconjunctival dirofilariasis in India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:244–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pane C. No ta su un elminto nematoide. Ann Acad Aspiranti. 1864;4:32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin PH, Lefebvre MG. Malaria and climate: sensitivity of malaria potential transmission to climate. Ambio. 1995;24:200–207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genchi C, Rinaldi L, Mortarino M, et al. Climate and Dirofilaria infection in Europe. Vet Parasitol. 2009;163:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvell CD, et al. Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science. 2002;296:2158–2162. doi: 10.1126/science.1063699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senthilvel K, et al. A case of subcutaneous dirofilariasis in a woman in Kerala. Ind Vet J. 1999;76:263–264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padmaja P, et al. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis in Southern India: a case report. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;99:437–440. doi: 10.1179/36485905X36253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khurana S, Singh G. Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis in India: a report of three cases with brief review of literature. Ind J Med Microbiol. 2010;28:394–396. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.71836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph E, Matthai AA, et al. Subcutaneous human dirofilariasis. J Parasit Dis. 2010;35:140–143. doi: 10.1007/s12639-011-0039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Permi HS, Kishan, et al. Subcutaneous human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilariarepens: report of two cases. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3:199–201. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.81702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Souza R, Jakribettu RP, et al. Subcutaneous nodule: a case of Dirofilaria. Int J App Basic Med Res. 2013;3:64–65. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.112243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nath R, Bhuyan S, Dutta H, Saikia L. Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis in Assam. Trop Parasitol. 2013;3:75–78. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.113920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khyriem AB, Lynrah KG, Lyngdoh WV. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:403–405. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.118869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manuel S, Surej LK, Khalam SA. Oral dirofilariasis: report of a case arising in the buccal vestibular region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2015;27:418–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoms.2014.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janardhanan M, Rakesh S, Savithri V. Oral dirofilarasis. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25:236–239. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.135932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Premakumar P, Nair V, Nair B, Thomas S. Discussion of a case of Dirofilariasis presenting as a nodular mass. Int J Medical Health Sci. 2014;3:223–225. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishna AS, Bilahari N, Savithry Subcutaneous infraorbitaldirofilariasis. Indian J Dermato. 2015;60:420. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.160513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desai RS, Pai N, Singh JS. Oral dirofilariasis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:593–594. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.167342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balaji SM. Live dirofilaria in buccal mucosa. Indian Journal of Dental Research. 2014;25:546–547. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.142581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attygalle D, Dissanaike AS (1970) The third case of human infection with dirofilaria sp. from Ceylon. HD Srivastava Commemvolume Izatnagar 453–454

- 32.Dissanaike AS, Abeyewickreme W, Wijesundera MD. Human dirofilariasis caused by dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens in srilanka. Parassitologia. 1997;39:375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratnatunga N, Wijesundera MS. Histopathological diagnosis of subcutaneous Dirofilariarepens infection in humans. Southeast Asian J Troop Med Public Health. 1999;30:370–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitakotuwage TN, Mendis BR, Edirisinghe JS (1999) Dirofilaria repens infection of the oral mucosa and the cheek. A case report. Dental Symposium Sri Lanka. RJ–CA: 125

- 35.Tilakaratne WN, Pitakotuwage TN. Intra-oral Dirofilariarepens infection: report of seven cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:502–505. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jayasinghe RD, Gunawardane SR, Sitheeque MM (2015) A Case Report on Oral Subcutaneous Dirofilariasis. Case Rep Infect Dis. Article Id 648278, 1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Senanayke MP, Infaq ML. Ocular and subcutaneous dirofilariasis in a Sri Lankan infant: an environmental hazard caused by dogs and mosquitoes. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2013;33:111–112. doi: 10.1179/2046905512Y.0000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pampiglione S, Fruttaldo L, Canestri TG. Human dirofilariasis: extraction of the living nematode from the upper lip. Pathologica. 1993;85:515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pampiglione S, Cagno MC, Savalli E, Guidetti F. Human muscle dirofilariasis of difficult diagnosis. Pathologica. 1996;88(2):97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cancrini G, Favia G, Merulla R, et al. Traditional and innovative tools to diagnose 8 new cases of human dirofilariosis occurred in Italy. Parassitologia. 1998;40:24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MaximovaT Bogachkina SI, Oshevskaya EA. Human nematodoses in Tula region. Kollekt Avtorov. 1991;55:56. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Postnova VF, et al. Dirofilariasis in man new cases. Medsk Parazitol. 1997;1:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laura H, et al. Human Subcutaneous Dirofilariasis. Russia Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:150–152. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Triantafillopoulos E. A case of human infection with Nematode in Messinia. Arch iatr Epist. 1952;8:58–59. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markopoulos AK, Trigonidis G, Papanayotou P. Submucous dirofilarriasis involving cheek. Report of a case. Ann Dent. 1990;49:34–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Auer H, et al. Einseltener Falleiner Dirofilariarepens infestation des Nebenhodens. Mitt ÖsterrGesTropenmed Parasitol. 1997;19:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tzanetou K, Gogou C, Giannoulopoulos A, et al. Fibrous subcutaneous nodule caused by Dirofilaria repens. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lapierre J, et al. Dirofilariasis in humans. Report of a case with localization in the cheek. Sem Hop. 1982;24(58):1575–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abou-Bacar A, Diallo M, Waller J, Cribier B, Candolfi E. Human subcutaneous dirofilariosis due to Dirofilariarepens. A case diagnosed in Strasbourg, France. Bull SocPathol Exot. 2007;100:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rivière D, Vatin L, Morvan J-B, Cathelinaud O. Dirofilariose intramassétérine. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2014;131(6):379–380. [Google Scholar]

- 51.EW, Tsang WM, Chan KF. Human dirofilariasis of the buccal mucosa: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32: 104-106 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Seddon SV, Peckitt NS, Davidson RN, Sugar AW. Helminth infection of the parotid gland. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50(2):183–185. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90368-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmed A, Cascarini L, Goodman A, et al. Cutaneous dirofilariasis affecting the parotid duct: a case report. Maxillofacial. 2010;10:107–109. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaouech E, Becheur M, Cheikh M. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis of the upper lip in Tunisia Sante. 2010;20:47–48. doi: 10.1684/san.2009.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reinhard E, Friedricha, Max H. Human Dirofilariarepens infection of the zygomatico-temporal. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2014;42:612–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pereira LL, Monteiro LC. Dirofilariasis involving the oral cavity: report of the first case from South America. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:361–363. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0025-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daroit NB et al. (2016) Submucosal nodule in buccal mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. pii: S2212–4403 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Collins BM, Jones AC, Jimenez F. Dirofilariatenuis infection of the oral mucosa and cheek. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:1037–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herzberg AJ, et al. Subcutaneous Dirofilariasis in Collier County, Florida, USA. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(8):934–939. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akst LM, et al. Dirofilarial infection presenting as a facial mass: case report of an emerging zoonosis. JAm J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vélez-Pérez A et al. (2016) Dirofilariasis Presenting as an Infiltrative Mass in the Right Buccal Space. Int J Surg Pathol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Maraghi S, et al. Human dirofilariasis due to dirofilaria repens in ahvaz—iran: a report of three cases. Pak J Med Sci. 2006;22:211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Radmanesh M, Saberi A, Maraghi S, Emad-Mostowfi N, Radmanesh M. Dirofilaria repens: a dog parasite presenting as a paranasal subcutaneous nodule. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:477–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fuehrer HP et al. Dirofilaria in humans, dogs, and vectors in Austria (1978–2014)—from imported pathogens to the endemicity of dirofilaria repens. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Böckie BC, Auer H, Sepp NT. Danger lurks in the Mediterranean. Lancet. 2010;11(37):2040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Enghelshtein AS, Zaporozhets GI. A case detection of Dirofilaria repens. Medskaya Parazit. 1973;42:358. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jelinek T, Hillen J, Loscher T. Human dirofilariasis. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:872–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb05054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Favia G (2000) Molecular diagnosis of Dirofilaria repens is not a dream. Letter to the editor. Diagn Microbiol Inf Dis. 37: 81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Regional Strategy (2015) From Malaria Control to Elimination in the WHO European Region 2006–2015. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Copenhagen 1–50

- 70.Pampiglione S, Trotti G. Pitfalls and difficulties in histological diagnosis of human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens. Microbiol, Infect Dis. 1999;34(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(98)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Geldelman D, Blumberg R, Sadun A. Ocular Loa Loa with cryoprobe extraction of subconjunctival worm. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:300–303. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(84)34302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van den Ende J, et al. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repensin a Belgian patient. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:274–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marconcini A, Magi M, Contin BH. Efficacy of ivermectin in preventing Dirofilariarepens infestation in dogs naturally exposed to contagion. Parassitologia. 1993;35:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]