Abstract

Background:

In the US, Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccines were first licensed in 2014. In 2015, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that parents of teens talk to their provider about receiving MenB vaccine, rather than issuing a routine recommendation. We assessed parental awareness of MenB vaccines and willingness to vaccinate their teens with MenB vaccines compared to MenACWY vaccines, which have been routinely recommended for many years.

Methods:

We surveyed parents of teens attending high school in 2017–18 during the Minnesota State Fair. Parents reported via iPad their knowledge of and concern about meningococcal disease and their awareness of and willingness to vaccinate with MenB and MenACWY vaccines. We assessed the relationship between meningococcal disease knowledge and concern, MenB and MenACWY vaccine awareness, and willingness to vaccinate with MenB and MenACWY using adjusted logistic regression.

Results:

Among 445 parents, the majority had not heard of the newly introduced MenB vaccines Bexsero® (80.0%; 95% CI: 76.0–83.6) or Trumenba® (82.0%; 95% CI: 78.1–85.5) or the MenACWY vaccines Menactra® or Menveo® (68.8%; 95% CI: 64.2–73.0). The majority were at least somewhat willing to vaccinate their teen with MenB vaccine (89.6%; 95% CI: 86.5, 92.3) and MenACWY vaccine (91.2%; 95% CI: 88.2, 93.7). Awareness of MenB vaccines (OR: 3.8; 95% CI: 1.2–12.2) and concern about meningococcal disease (OR: 3.1; 95% CI: 1.5–6.3) were significantly associated with willingness to vaccinate with MenB vaccine.

Conclusions:

Awareness of MenB vaccine is lacking among parents of teens but is an important predictor of willingness to vaccinate with the newly licensed MenB vaccines.

Keywords: Meningococcal vaccines, Meningococcal B, Awareness, Parents, Adolescents, Survey

1. Background

Meningococcal disease, a rare but serious acute illness caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis, is a significant public health concern. symptoms appear and progress rapidly and the illness results in high fatality or life-long sequelae even with proper treatment [1,2]. N. meningitidis carriage in the mucosal membranes of the nose and throat is common and the bacteria spread via saliva and respiratory droplets during close contact with an infected individual [3]. In the US, infants, teens and young adults are at highest risk of invasive disease [4,5]. Overall, the estimated incidence of meningococcal disease (all serotypes) in the US in 2017 was 0.11 cases per 100,000 population [6]. Multiple serogroups of N. meningitidis can cause disease. Meningococcal B (MenB) is responsible for an estimated 50% of cases among young adults [7] and numerous MenB outbreaks among college students have occurred over the past several years [8,9].

Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent against meningococcal disease. Vaccines that protect against meningococcal groups A, C, W and Y (MenACWY vaccines) have been available in the US for several decades while vaccines designed to protect against MenB were first licensed in the US in 2014 [10]. Currently, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routine vaccination with MenACWY polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines for all adolescents, with the first dose administered at age 11–12 years, followed by a booster dose at 16 years (Category A; routine recommendation) [1]. The ACIP first recommended MenB vaccines in 2015 [10–12]. Currently, the ACIP recommends routine vaccination with MenB vaccines for those aged 10 years or older who are at increased risk of infection (Category A; routine recommendation) [11,12]. The ACIP notes that “Category A recommendations are made for all persons in an age- or risk-factor-based group” [12]. For all teens and young adults aged 16–23 years not at increased risk, the ACIP has issued a permissive recommendation (Category B; decision based on individual clinical decision-making) indicating that teens may be vaccinated with a preference for vaccination between 16 and 18 years of age. The ACIP notes that “Category B recommendations are made for individual clinical decision making” [12] and actively encourages parents of teens and health care personnel to discuss meningococcal vaccines and to decide how best to protect against meningococcal disease [11,12].

In 2017, an estimated 85.1% of US teens aged 13–17 years had received one or more doses of MenACWY vaccine [13]. Vaccination uptake ranged from state to state with a low of 60.7% coverage in Wyoming to a high of 95.3% in Georgia [13]. A recent 2017 survey estimated that only 14.5% of 17 year olds in the US have received one or more doses of MenB vaccine [14]. The Healthy People 2020 goal is to reduce the number of annual, laboratory confirmed cases of meningococcal disease by 10% among all age groups [15]. Increasing vaccine uptake and ensuring the sustainability of high uptake of both MenAWCY and MenB vaccines is critical to achieving this goal. While studies have been conducted in other countries to address knowledge and attitudes about the recently developed MenB vaccines [16–23], only one study has investigated awareness of MenB vaccine in the US [24]. Breakwell et al. investigated uptake in the context of an ongoing MenB outbreak and found 51% MenB vaccine coverage among a college student population at a time when the vaccine was not yet licensed; vaccinees were motivated by the knowledge that meningitis is a serious disease and that vaccination is the best way to protect oneself [24]. Now that MenB vaccines are licensed in the US, recommended, and more widely available, parents of teenagers have the opportunity to have their children vaccinated with both MenB and MenACWY vaccines to protect against 5 disease-causing serogroups. While parents are actively encouraged to ask their physician about MenB vaccines, little is known about parental awareness of or attitudes towards MenB vaccines.

We conducted a study to determine how knowledgeable parents are about meningococcal vaccines and meningococcal disease, and how willing they are to have their child vaccinated with MenB vaccines compared to MenACWY vaccines. Specifically, we aimed to (1) assess parental knowledge of meningococcal disease, concern about meningococcal disease, and awareness of meningococcal vaccines, (2) assess and compare parental willingness to vaccinate their teens with MenB and MenACWY vaccines, and (3) determine the relationship between parents’ awareness of meningococcal vaccines and knowledge of and concern about meningococcal disease and to their willingness to vaccinate their child with both MenB and MenACWY vaccines.

2. Methods

We conducted an in-person, cross-sectional survey at the University of Minnesota’s (UMN) Driven to Discover (D2D) research facility during the 2017 Minnesota State Fair. In 2017, 1,997,320 people attended the 12-day event, the highest attendance since the fair began in 1859 [25]. Prior to administering the survey, we completed a small pilot study to refine the questions.

2.1. Participant recruitment

Potential participants who approached our study booth were invited to take the survey. Potential participants were eligible if they had a child who would be attending high school during the 2017–18 academic year and if they read and understood English. Potential participants who confirmed their eligibility reviewed a consent information sheet and self-administered the electronic questionnaire anonymously using an iPad. The study was reviewed by the UMN Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Survey design

The survey consisted of 27–31 questions, depending upon the skip pattern (see Supplementary Appendix Table A1 for the full survey), asking participants about their demographic characteristics, knowledge about meningococcal disease, concern about meningococcal disease, awareness of meningococcal vaccines, and their willingness to vaccinate their child with both MenACWY vaccines and MenB vaccines. Throughout the survey, participants were presented with educational information about meningococcal disease, including common symptoms, severity and risk, and about meningococcal vaccines, including the recommended ages and schedule for administering MenACWY and MenB vaccines (included in Supplementary Appendix Table A1). Survey responses were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software, a secure, web-based software designed to support research studies [26].

2.3. Data analysis

We evaluated participants’ knowledge of meningococcal disease by asking them to identify key characteristics among several options: how the disease is transmitted, how common it is relative to other diseases, how severe it is, what the typical symptoms are, and which age group among the options is at highest risk. We created a knowledge scale, assigning participants one point for each correct answer including one point if they selected at least one typical symptom and no incorrect symptom. Participants were categorized as “more knowledgeable” if they answered 3 or more questions correctly and “less knowledgeable” if they answered 2 or fewer questions correctly.

We evaluated participants’ concern about meningococcal disease using a 4-point Likert scale. Participants were categorized as “at least somewhat concerned” if they indicated that they were “somewhat concerned,” “concerned,” or “very concerned” that they or a loved one might get bacterial meningitis and “not concerned” if they selected “not at all concerned.”

We evaluated participants’ awareness of meningococcal vaccines by asking them whether they had heard, prior to the survey, of either of the MenACWY vaccines Menactra® (Sanofi Pasteur) or Menveo® (Novartis) and whether they had heard of either of the MenB vaccines Trumenba® (Pfizer) or Bexsero® (GSK). Participants were categorized as aware of MenACWY vaccines if they had heard of at least one MenACWY vaccine before the survey versus not aware of MenACWY vaccines; participants were categorized as aware of MenB vaccines if they had heard of at least one MenB vaccine before the survey versus not aware of MenB vaccines.

To assess participants’ willingness to vaccinate, we asked how willing they would be to vaccinate their child with either MenACWY vaccine or with either MenB vaccine. Participants were categorized as “at least somewhat willing” if they selected “somewhat willing,” “willing,” or “very willing” and “not willing” if they were “not at all willing” to vaccinate their teen. MenACWY and MenB vaccines were assessed separately.

Because a complete primary series of vaccinations to protect against all 5 serogroups for which vaccines are currently licensed requires at least 3–4 shots (of MenACWY and MenB vaccines), we also asked participants to select the maximum number of shots they would be willing to give their child in order to fully protect them against as many types of meningococcal disease as possible. Participants were categorized as “willing to fully vaccinate against MenABCWY” if they selected “at least 3–4 shots” and “not willing to fully vaccinate” if they selected fewer than 3 shots.

Though parental report of teens’ MenACWY vaccination status has been shown to lead to underreporting [27], we also asked parents to report whether their child had ever received MenACWY vaccine and/or MenB vaccine for completeness and we asked the primary reason their child had or had not received either vaccine.

2.4. Statistical methods

For each question, we report the percent of participants providing each response and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the point estimate based on the exact Clopper-Pearson CI. Spearman’s rho was calculated to quantify the correlation between categorical variables. We used logistic regression to assess the association between several covariates: parental awareness of MenB vaccines, parental awareness of MenACWY vaccines, parental knowledge of meningococcal disease based on the knowledge scale, parental concern about meningococcal disease based on the Likert scale, and three outcomes: (1)parental willingness to vaccinate their child with MenB vaccine, (2) parental willingness to vaccinate their child with MenACWY vaccine, and (3) parental willingness to fully vaccinate their child with enough shots to protect against the 5 serogroups for which vaccines are currently licensed (MenABCWY). For each of the three models, we controlled for potential confounders: parental age (continuous), parental race (white versus non-white), parental ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino(a) versus not Hispanic/Latino(a)), parental education (at least a high school degree versus more than a high school degree), and child age in years (≤14, 15, 16, ≥17). Data management and analysis was undertaken using R Version 3.4.1.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Of the 445 parents who completed the survey, the average age was 47.6 years, the majority were female (71.7%), white (90.1%), not Hispanic or Latino/a (95.3%), had a Bachelor’s degree or higher (64.9%), and lived within the Minneapolis-St Paul metropolitan area (64.7%) (Table 1). The average age of the child to whom the survey questions referred was 16 years. Overall, 89.2% of parents reported that their child had received at least one vaccine in the past (any type at any age).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the 445 Parents of High School-Aged Children Who Completed the Survey.a

| Characteristic | Response | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Years, Mean (SD) | 47.6 | 6.1 |

| Sex | Male | 125 | 28.1 |

| Female | 319 | 71.7 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Race | American Indian or Alaska Native | 5 | 1.1 |

| Asian or Asian American | 10 | 2.3 | |

| Black or African American | 13 | 2.9 | |

| Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.0 | |

| White | 401 | 90.1 | |

| Multiracial | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Other | 13 | 2.9 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino(a) | 7 | 1.6 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino(a) | 424 | 95.3 | |

| Missing | 14 | 3.1 | |

| Highest Education | Elementary school | 0 | 0.0 |

| Some high school | 2 | 0.5 | |

| High school diploma or GED | 30 | 6.7 | |

| Associate’s degree | 65 | 14.6 | |

| Some college, no degree | 59 | 13.3 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 171 | 38.4 | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 118 | 26.5 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Live in the 7-county Minneapolis-St.Paul metropolitan area | Yes | 288 | 64.7 |

| No (including outside MN) | 155 | 34.8 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.4 |

Abbreviations: n = frequency, % = percentage, SD = standard deviation.

Categorical variables presented as n (%); Continuous variables presented as mean (SD).

3.2. Parental knowledge about and concern for meningococcal disease

The complete results of the survey are given in the Supplementary Appendix Table A1. Nearly all participants (91.5%; 95% CI: 88.5, 93.9) were aware of meningococcal disease, and of those 76.9% (95% CI: 72.5, 80.9) reported being at least somewhat knowledgeable about the disease. The mean score on the knowledge scale was 2.8 (out of 5). However, nearly all participants (90.6%; 95% CI: 87.5, 93.1) thought meningococcal disease is more common than it is in the US. Overall, 70.3% (95% CI: 65.9%, 74.5%) of participants reported that they are at least somewhat concerned about the disease.

3.3. Parental awareness of meningococcal vaccines

Overall, 75.5% (95% CI: 71.2, 79.4) of parents reported that they were aware of meningococcal vaccines in general and 71.7% (95% CI: 66.6, 76.5) of those respondents considered themselves at least somewhat knowledgeable about meningococcal vaccines. About two thirds of all respondents (68.8%; 95% CI: 64.2, 73.0) had not heard of the MenACWY vaccines Menactra® or Menveo® and an even higher proportion had not heard of the MenB vaccines Bexsero® (80.0%; 95% CI: 76.0, 83.6) or Trumenba® (82.0%; 95% CI: 78.1, 85.5). Only 7.0% (95% CI: 4.8, 9.7) of participants knew that the most recently licensed vaccines protect against serogroup B disease.

3.4. Parental willingness to vaccinate their teen against MenB

Participants’ reported willingness to vaccinate their teen with MenB and MenACWY vaccine were similar, with 89.6% at least somewhat willing to vaccinate with Bexsero® or Trumenba® (95% CI: 86.5, 92.3) and 91.2% at least somewhat willing to vaccinate with Menactra® or Menveo® (95% CI: 88.2, 93.7). We found a strong correlation (Spearman’s rho: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.89, 0.92) between participants’ willingness to vaccinate with MenB and participants’ willingness to vaccinate with MenACWY. Nearly half (46.3%; 95% CI: 41.6, 51.0) of participants were willing to fully vaccinate their child with at least 3–4 doses of vaccine to protect against the 5 meningococcal serogroups (ABCWY) for which vaccines are currently licensed. At the end of the survey, the majority of participants indicated that they would like more information from their doctor about both MenB and MenACWY vaccines (81.1% [95% CI: 77.2, 84.7] and 79.6% [95% CI: 75.5, 83.2], respectively). Overall, 55.3% (95% CI: 50.5, 60.0) of participants were at least somewhat interested in receiving text or email notifications from their doctor about their child’s eligibility for meningococcal vaccines.

3.5. Parental self-reported history of vaccinating their teen

While 37.9% (95% CI: 33.2, 42.7) of participants reported that their child had received at least one MenACWY vaccination, 34.5% (95% CI: 30.0, 39.3) did not know if their child had been vaccinated. In addition, while 20.4% (95% CI: 16.6, 24.6) of participants reported that their child had received at least one MenB vaccination, 40.8% (95% CI: 36.0, 45.7) did not know if their child had been vaccinated. The top reasons parents indicated that their child had not received MenACWY or MenB vaccine was that they did not know about this vaccine (40.0% [95% CI: 31.0, 49.6] and 31.5% [CI: 24.4, 39.2], respectively) or their health care provider did not recommend the vaccine (33.9% [95% CI: 25.3, 43.3] and 32.7% [95% CI: 25.6, 40.5], respectively).

3.6. Relationship between parental concern for meningococcal disease, knowledge of meningococcal disease, plus awareness of meningococcal vaccines and parental willingness to vaccinate their teen with MenB and MenACWY vaccines

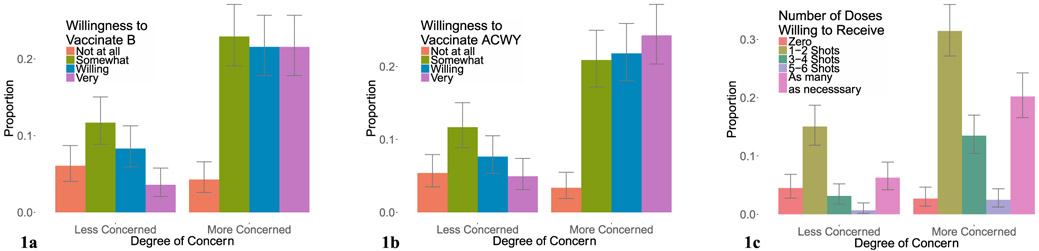

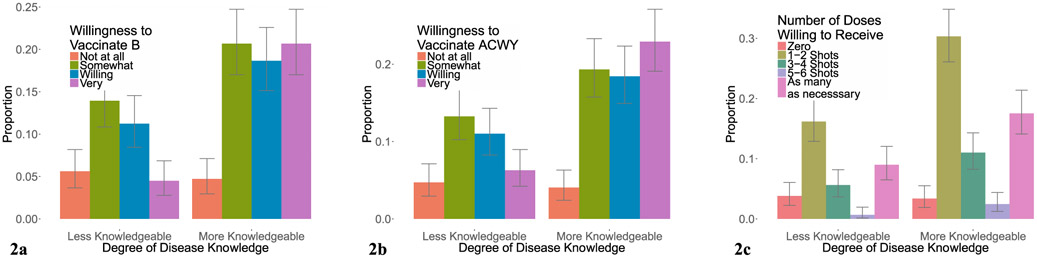

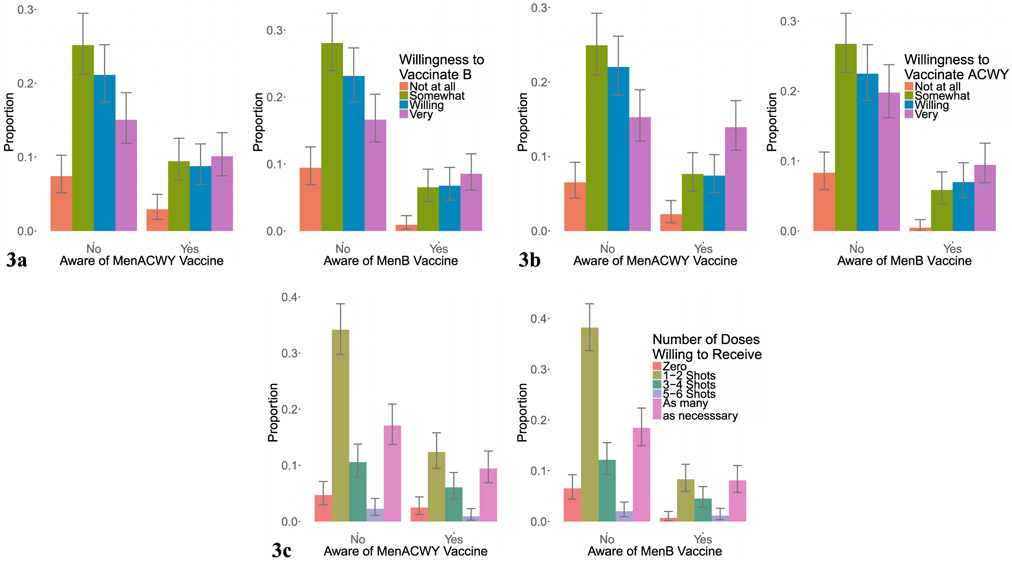

The relationship between parental concern about meningococcal disease and willingness vaccinate their child with MenB, MenACWY, or to fully vaccinate against the 5 groups (MenABCWY) with at least 3–4 shots is shown in Fig. 1a–c. The relationship between knowledge of meningococcal disease and willingness to vaccinate with MenB, MenACWY, and to fully vaccinate to protect against the 5 serogroups for which vaccines are currently licensed is shown in Fig. 2a–c. The relationship between awareness of MenB and awareness of MenACWY vaccines and willingness vaccinate with MenB, MenACWY, and to fully vaccinate is shown in Fig. 3a–c.

Fig. 1.

Concern about Meningococcal Disease and Willingness to Vaccinate. The relationship between parental concern about meningococcal disease and willingness vaccinate their child with MenB vaccine (a), MenACWY vaccine (b), and the total number of vaccine doses willing to receive (c).

Fig. 2.

Knowledge of Meningococcal Disease and Willingness to Vaccinate. The relationship between parental knowledge of meningococcal disease and willingness vaccinate their child with MenB vaccine (a), MenACWY vaccine (b), and the total number of doses of vaccine willing to receive (c).

Fig. 3.

Awareness of MenB and MenACWY Vaccines and Willingness to Vaccinate. The relationship between parental awareness of MenB and MenACWY vaccines and willingness vaccinate their child with MenB vaccine (a), MenACWY vaccine (b), and the total number of doses of vaccine willing to receive (c).

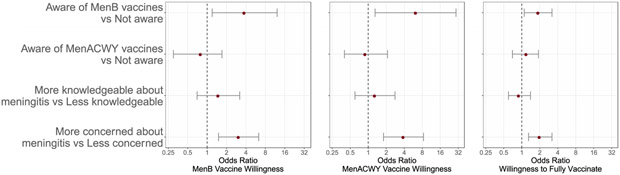

Based on our logistic regression models, parents who were aware of at least one of the MenB vaccines compared with those who were not aware had significantly higher odds of being willing to vaccinate their child with MenB vaccine (OR: 3.8; 95% CI: 1.2, 12.2; p = 0.03), with MenACWY vaccine (OR: 6.3; 95% CI: 1.3, 29.4; p = 0.02), and with enough doses to fully vaccinate their child (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1, 3.2; p = 0.02) (Fig. 4). In addition, participants who were at least somewhat concerned about meningococcal disease compared to those not at all concerned had a higher odds of being willing to vaccinate their child with MenB vaccine (OR: 3.1; 95% CI: 1.5, 6.3; p = 0.002), with MenACWY vaccine (OR: 3.9; 95% CI: 1.8, 8.4; p < 0.001), and with enough doses to fully vaccinate their child to protect against 5 meningococcal groups (OR 2.0; 95%CI: 1.3, 3.2; p = 0.002) (Fig. 4). There was no evidence that the odds of willingness to vaccinate (for any of the three outcomes) differed between parents who had more knowledge about meningococcal disease compared to parents with less knowledge (see complete results in Fig. 4) or between parents who were aware of at least one of the MenACWY vaccines compared to those who had not heard of either before the survey.

Fig. 4.

Assessment of the association between parental awareness of MenB vaccines, awareness of MenACWY vaccines, knowledge of meningococcal disease, and concern about meningococcal disease with (panel 1) willingness to vaccinate one’s child with MenB vaccine, (panel 2) willingness to vaccinate one’s child with MenACWY vaccine, or (panel 3) willingness to fully vaccine against 5 serogroups (receiving at least 3–4 shots). (Logistic regression models for each of the three outcomes were adjusted for parental sex (males vs females), parental age (continuous), parental race (white vs non-white), parental ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino(a) vs non-Hispanic/Latino(a)), parental education (at least a high school degree vs more than a high school degree), and child age in years (<=14, 15, 16, >=17).)

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that the majority of parents of teenagers surveyed lack awareness of the recently licensed MenB vaccines even though the vaccines had been licensed for 2–3 years at the time of our survey. Despite this lack of awareness, a high proportion of parents indicated that they are willing to have their child vaccinated with MenB vaccines to protect them against MenB disease. Since both MenB and MenACWY vaccines are needed in order to protect individuals as completely as possible against the most common causes of bacterial meningitis reported in the US, this degree of parental willingness is encouraging. It suggests that parents are open to receiving additional information and engaging in discussions about meningococcal vaccines. Indeed, 4 out of 5 parents reported that they would like their physician to provide more information about MenB and MenACWY vaccines. A recent study found that physicians themselves lack knowledge about MenB vaccines and often fail to discuss them with their patients [28]. Lack of parental awareness coupled with knowledge gaps among physicians are significant barriers to MenB vaccination. Resources are available to educate and support providers as they discuss the risk of meningococcal disease and the availability of meningococcal vaccines with their patients [29–32]. We found that both awareness of the MenB vaccines and concern about meningococcal disease were associated with a significantly higher willingness of parents to vaccinate their child for each of the three outcomes we investigated: (1) willingness to vaccinate with MenB vaccines, (2) willingness to vaccinate with MenACWY vaccines, and (3) willingness to fully vaccinate to protect against 5 disease-causing groups (at least 3–4 shots).

Taken together, our findings strongly suggest that increasing awareness of MenB vaccines among parents is critical to allow parents to make informed decisions. As noted, current ACIP recommendations encourage parents to discuss MenB vaccination with their child’s health care providers, but our results suggest that since awareness of MenB vaccines among parents of teenagers is so low, parents are unlikely to raise the topic themselves. Health care providers should consider initiating conversations about the risk of meningococcal disease and the availability of MenB vaccines to improve awareness among both parents and teens. Research on other adolescent vaccines, specifically HPV vaccine, has provided robust evidence of the importance of provider recommendations in increasing vaccine uptake [33], and such lessons could improve meningococcal vaccine uptake, as well.

Discussions with health care personnel could also be instrumental in providing education and addressing misconceptions about meningococcal disease since we also found that few parents could correctly identify the most common symptoms of bacterial meningitis and that many parents thought meningococcal disease was more common than it is. Such conversations about the risk of meningococcal disease and opportunities for vaccination would enable parents to work together with their providers to consider how best to protect their children from meningococcal disease. Of note, our results suggest that parents have heard of meningococcal vaccines in general, but that few had specific knowledge about the vaccines currently available. This finding could be used by providers as a starting point to initiate conversations and deliver appropriate messages about risks and benefits to parents, the majority of whom also indicated an interest in receiving additional information. Currently, MenB vaccines are recommended for routine use among high-risk adolescents and permissive use among all adolescents; at least 14 colleges and universities are now requiring MenB vaccine for incoming students while approximately a dozen others are considering such a requirement [34]. Greater awareness is needed among parents of high school students to minimize missed opportunities for meningococcal prevention throughout the teenage years.

Our survey contributes key insight about parental awareness of and willingness to vaccinate their teens with the newly introduced MenB vaccines. However, our study was limited in that we drew a convenience sample of parents which may not be representative of parents in the US broadly or even in Minnesota. Yet, our study contributes novel and timely evidence to understand the need for greater parental awareness MenB vaccines, a topic for which there is very limited data. Previous studies investigating the willingness to receive MenB vaccines have been undertaken only in the context of an outbreak [24] or in countries outside the US where vaccination recommendations differ significantly [16–23]. We have provided evidence that awareness of MenB vaccine is lacking among parents of teens in the US and that awareness of MenB vaccines, along with concern for meningococcal disease, are important predictors of willingness to vaccinate with the newly licensed MenB vaccines. Our results highlight the need for additional education about meningococcal disease prevention so that parents are informed about the opportunity to ensure that their teens are as fully protected as possible against meningococcal disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank our data collection volunteers for their assistance recruiting for the survey: Joanne Dehnbostel, Melanie Firestone, Emily Groene, Audrey Hanson, Howie Hsieh, Julia Lang, Tessa Lasswell, Zach Laughlin, Heather Oas, Kara Ulmen and Rachel Wirthlin.

Funding sources

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01AI132496 (PI: Nicole E. Basta) and the Office of The Director of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DP5OD009162 (PI: Nicole E. Basta). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Funding sources had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to publish.

Abbreviations:

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- MenACWY vaccine

serogroups A, C, W, and Y meningococcal vaccine

- MenABCWY

meningococcal serogroups A, B, C, W and Y

- MenB vaccine

serogroup B meningococcal vaccine

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.11.078.

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- [1].Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Briere EZ, Meissner HC, et al. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2013;62(RR-2):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kaplan SL, Schutze GE, Leake JA, Barson WJ, Halasa NB, Byington CL, et al. Multicenter surveillance of invasive meningococcal infections in children. Pediatrics 2006;118(4):e979–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chang Q, Tzeng YL, Stephens DS. Meningococcal disease: changes in epidemiology and prevention. Clin Epidemiol 2012;4:237–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thigpen MC, Whitney CG, Messonnier NE, Zell ER, Lynfield R, Hadler JL, et al. Bacterial meningitis in the United States, 1998-2007. N Engl J Med 2011;364(21):2016–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, Mayon-White R, Phillips C, Bailey L, et al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet 2006;367(9508):397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). Enhanced meningococcal disease surveillance report, 2017 Available from: <www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/downloads/NCIRD-EMS-Report-2017.pdf>. Accessed November 2018; 2018

- [7].Soeters HM, McNamara LA, Whaley M, Wang X, Alexander-Scott N, Kanadanian KV, et al. Serogroup B Meningococcal Disease Outbreak and Carriage Evaluation at a College - Rhode Island, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(22):606–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].National Meningitis Association. Serogroup B meningococcal disease outbreaks on U.S. college campuses; 2016. Available from: <http://www.nmaus.org/disease-prevention-information/serogroup-b-meningococcal-disease/outbreaks/>. Accessed September 2018.

- [9].Mbaeyi SA, Blain A, Whaley MJ, Wang X, Cohn AC, MacNeil JR. Epidemiology of meningococcal disease outbreaks in the United States, 2009-2013. Clin Infect Dis 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, Patel M, MacNeil JR, Centers for Disease C. Use of Serogroup B Meningococcal Vaccines in Persons Aged >=10 years at increased risk for Serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(22):608–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Patton ME, Stephens D, Moore K, MacNeil JR. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp Serogroup B meningococcal vaccine - advisory committee on immunization practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(19):509–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Patel M, Martin SW. Use of Serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(41):1171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Adolescent Meningococcal Conjugate (MenACWY) Vaccination Coverage Report. August 2018. Available from:<https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/teenvaxview/data-reports/menacwy/reports/2017.html>. Accessed November 2018.

- [14].Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Mbaeyi SA, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13-17 Years - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(33):909–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Healthy People 2020 Goals and Objectives for Immunization and Infectious Disease: United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Available from: <https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives> Accessed: July 2018.

- [16].Jackson C, Yarwood J, Saliba V, Bedford H. UK parents’ attitudes towards meningococcal group B (MenB) vaccination: a qualitative analysis. BMJ open 2017;7(4):e012851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Morrone T, Napolitano F, Albano L, Di Giuseppe G. Meningococcal serogroup B vaccine: Knowledge and acceptability among parents in Italy. Hum Vacc Immunother 2017;13(8):1921–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Le Ngoc Tho S, Ader F, Ferry T, Floret D, Arnal M, Fargeas S, et al. Vaccination against serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis: Perceptions and attitudes of parents. Vaccine 2015;33(30):3463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mameli C, Faccini M, Mazzali C, Picca M, Colella G, Duca PG, et al. Acceptability of meningococcal serogroup B vaccine among parents and health care workers in Italy: a survey. Hum Vacc Immunother 2014;10(10):3004–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Marshall HS, Chen G, Clarke M, Ratcliffe J. Adolescent, parent and societal preferences and willingness to pay for meningococcal B vaccine: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Vaccine 2016;34(5):671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Takla A, Wichmann O, Koch J, Terhardt M, Hellenbrand W. Survey of pediatricians in Germany reveals important challenges for possible implementation of meningococcal B vaccination. Vaccine 2014;32(48):6349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].de Waure C, Quaranta G, Ianuale C, Panatto D, Amicizia D, Apprato L, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of the Italian population towards Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae and HPV diseases and vaccinations: A cross-sectional multicentre study. Public health 2016;141:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].MacDougall DM, Langley JM, Li L, Ye L, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Top KA, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of university students, faculty, and staff during a meningococcal serogroup B outbreak vaccination program. Vaccine 2017;35(18):2520–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Breakwell L, Vogt TM, Fleming D, Ferris M, Briere E, Cohn A, et al. Understanding Factors Affecting University A Students’ Decision to Receive an Unlicensed Serogroup B Meningococcal Vaccine. J Adolesc Health 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Minnesota State Fair Attendance Available online: <https://www.mnstatefair.org/about-the-fair/attendance/>. Accessed 2018.

- [26].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dorell CG, Jain N, Yankey D. Validity of parent-reported vaccination status for adolescents aged 13-17 years: National Immunization Survey-Teen, 2008. Public Health Rep 2011;126 (Suppl. 2):60–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kempe A, Allison MA, MacNeil JR, O’Leary ST, Crane LA, Beaty BL, et al. Adoption of Serogroup B Meningococcal Vaccine Recommendations. Pediatrics 2018;143(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Meningitis B Action Project. Know. Act.Prevent Available at: <https://meningitisbactionproject.org/get-involved/> Accessed November 2018.

- [30].US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal Vaccination for Adolescents: Information for Healthcare Professionals Available at: <https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/hcp/adolescentvaccine.html> Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Committee On Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for Serogroup B Meningococcal Vaccine for Persons 10 Years and Older. Pediatrics 2016;138(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].American Academy of Family Physicians. Meningococcal disease vaccine 2016. Available at: <www.aafp.org/patient-care/public-health/immunizations/disease-population/meningococcal.html> Accessed November 2018.

- [33].Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12(6):1454–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Meningitis B Action Project. The Meningitis B Mandate Tracker <https://meningitisbactionproject.org/menbmandatetracker/> Accessed July 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.