Abstract

Background:

Persons living with HIV (PLHIV) have an increased risk of heart failure (HF). However, little is known about outcomes among PLHIV with HF. The study aim was to compare HF outcomes among PLHIV with HF vs. individuals without HIV with HF.

Methods:

Our cohort included 2,308 individuals admitted with decompensated HF. We compared baseline characteristics, 30-day HF readmission, cardiovascular (CV), and all-cause mortality. Within PLHIV, we assessed outcomes stratified between CD4 count, viral load (VL), and tested the association between traditional and HIV-specific parameters with 30-day HF readmission.

Results:

There were 374 (16%) PLHIV with HF. Among PLHIV, 92% were on ART and 63% had a VL <200 copies/ml. Groups were similar with respect to age, sex, race/ethnicity, and CV risk factors. In follow-up, PLHIV had increased 30-day HF readmission (49 vs. 32%), CV (26 vs. 13.5%), and all-cause mortality rates (38 vs. 22%). Among PLHIV, cocaine use. HIV-specific parameters (CD4, VL), and CAD were predictors of 30-day HF readmission. Specifically, among PLHIV, those with detectable VL had higher 30-day HF readmission and CV mortality, while PLHIV with undetectable VL had a similar 30-day HF readmission rate and CV mortality to uninfected controls with HF. Similar outcomes were observed across strata of LVEF and by CD4.

Conclusion:

PLHIV with a low CD4 count or detectable VL have an increased 30-day HF readmission rate as well as increased CV and all-cause mortality. In contrast, PLHIV with a higher CD4 count and undetectable VL have similar HF outcomes to uninfected controls.

Keywords: Heart failure, Human immunodeficiency virus, Heart failure re-admission, Cardiovascular

Introduction

Access to combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically increased survival among people living with HIV (PLHIV), transforming HIV into a chronic illness 1, 2. Moreover, the proportion of PLHIV >50 years old is rising across all regions – particularly in high resource regions 3. Individuals aging with HIV, however, face a heightened risk of cardiovascular comorbidities, including heart failure with both a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) 4, 5. Few studies have examined ways in which HIV status influences HF outcomes. We previously reported in a small study that women with HIV and HF have increased HF hospitalization rates, longer HF hospitalizations, and increased cardiovascular (CV) and all-cause mortality as compared with non-HIV-infected women with HF 6. In this prior study, the predominant type of HF was HFpEF, and men were not represented. The present investigation is the first to examine in a large, mixed-sex, contemporary US-based cohort whether outcomes differ among individuals with and without HIV hospitalized with HFrEF as well as HFpEF.

Methods

Study design and patient population

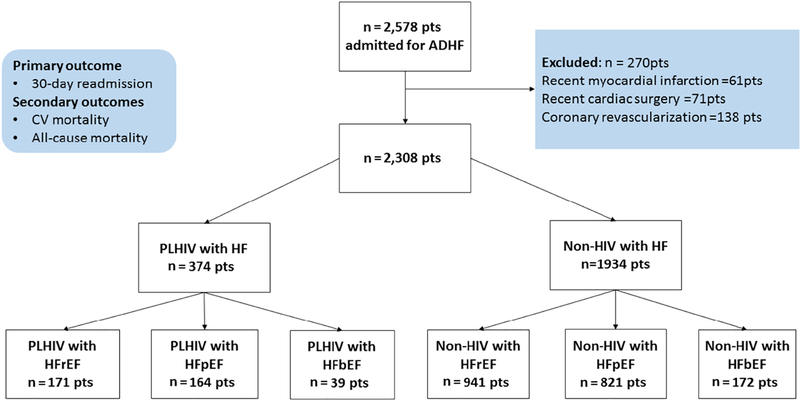

After obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, we created a registry of all 2,578 patients admitted to a single academic center in 2011 with decompensated HF (Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Bronx, New York). The primary aim of the registry was to compare outcomes and predictors of HF outcomes among PLHIV and controls. An acute decompensated HF admission was identified by HF ICD-9 codes (428.21, 428.31, 428.23, 428.33, 428.41 and 428.43), and after individual electronic health record (EMR) review, a final confirmed diagnosis was given to patients who fell into the consensus criteria based on previously published literature 7 (Supplemental Table 9). For this study, we used the same cohort as previously described by our group 8. We excluded those individuals with a recent (≤3 months) history of myocardial infarction (n=61), cardiac surgery (n= 71), and coronary revascularization (n= 138). The remaining 2,308 patients were divided into two groups: PLHIV (n=374) and persons without HIV (non-HIV-infected, n=1,934). Myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery, and coronary revascularization were identified with both ICD codes and confirmed with extensive chart review of these patients. The patients among the control population had not undergone HIV testing and were presumed to be HIV negative. The cohort was further stratified by heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, LVEF <40%), HF with borderline LVEF (HFbEF, LVEF 40–49%), and HF with preserved EF (HFpEF, LVEF ≥50%), Figure 1. The individual electronic health records of all 2,308 patients were reviewed and HIV diagnoses were ascertained.

Figure 1 legend:

Consort diagram for the study. ADHF = Acute decompensated heart failure. Pts = Patients, CV = Cardiovascular, PLHIV = Persons living with Human immunodeficiency virus. LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction. HFrEF= Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFpEF= Heart failure with preserve ejection fraction, HFbEF= Heart failure with borderline ejection fraction.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was 30-day HF readmission rate defined according to European Society of Cardiology (ESC) consensus criteria 9. The follow-up period began on the date of discharge from the first 2011 HF hospitalization until the last follow up within two years of the date of death. As per the hospital protocol, most of the patients with a primary diagnosis of HF on admission received a post-discharge follow-up within 10 days of the discharge date in the heart failure or cardiology clinic. Both (PLHIV and non-HIV controls) groups were followed over 2-years with median follow up period of 19 months among both groups. Our secondary outcomes included rates of CV mortality and all-cause mortality. CV death was defined as death due to HF, sudden cardiac death, arrhythmias, and acute ischemic events 10. Death was determined through Social Security death index (SSDI). All outcomes were confirmed by physician-adjudicated individual EHR review. If the documentation of the cause of death was not available, the case was listed in all-cause mortality but not in CV mortality. If no follow up for the patient was available, the patient was not readmitted, or reported in death records, he or she was assumed to have survived throughout the follow-up period. Outcomes were adjudicated by physicians blinded to HIV status.

Covariates

Through EHR review, data on traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors including hypertension (HTN), dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (CAD), sleep apnea, body mass index (BMI), any prior or active cigarette smoking, and any prior or active cocaine use were collected, as previously defined 6, 11, 12. The values for LVEF (estimated via biplane method) and PASP (measured from tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity and right atrial pressure) were obtained from echocardiogram 13 performed during index HF hospitalization. For patients who had >1 echocardiogram during hospitalization, the measurements were obtained from the first available upon hospitalization. Through EHR review, data were also collected on medication use at discharge from the index HF hospitalization. Details on HIV-specific parameters (current antiretroviral therapy, ART; duration of ART, CD4, VL) were recorded from those available closest to the time of discharge from the index HF hospitalization (91% were within 1 month of hospitalization).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean and SD or median (IQR), as appropriate, based on normality, and categorical variables were presented as percentages. For the primary assessments, two groups were defined as follows: PLHIV with HF and non-HIV-infected individuals with HF. Continuous data were compared with the use of unpaired Student t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square or the Fisher exact test. Survival curves were plotted using Kaplan Meier curves. To facilitate sub-group analyses, the group of PLHIV with HF was further stratified based on either CD4 count at the time of index HF hospitalization (≥ or <200 cells/mm3), (≥ or <500 cells/mm3) or viral load at the time of index HF hospitalization (≥ or <200 copies/ml). Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to determine the association between baseline covariates (including HIV status) and 30-day HF readmission rate. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses for 30-day HF readmission rate were constructed using a p<0.01 on the univariate analysis for entry. Both viral load and CD4 count were not included in the multivariate model due to the overlap between those individuals with a low CD4 count and a high viral load. Otherwise, statistical significance was defined using a two-tailed p-value ≤0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 23.

Results

Demographics and baseline characteristics

Amongst 2,308 individuals with HF at a single US tertiary care hospital in 2011, 374 were known to have HIV (PLHIV) while 1,934 were not. Among PLHIV, 92% (343/374) were on ART at the time of discharge and the median duration of ART use was nine years (IQR 4–16 years). The mean CD4 count was 368 cells/mm3 and 53% (199/374) had a CD4 count of ≥200 cell/mm3. Out of 374 PLHIV, 63% (235/374) had a VL <200 copies/ml. As per Table 1, those with and without HIV did not differ with respect to age, sex, race/ethnicity, or the prevalence of traditional CV risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cigarette smoking. The admission heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and LVEF during admission were also similar between groups. However, among PLHIV with HF, pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) was higher (45±9.5 vs. 40±9.0 mmHg, p<0.001), as was cocaine use (36 vs. 19%, p<0.001) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (13% vs 7%, p<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics PLHIV vs non-HIV

| PLHIV (n=374) | Non-HIV (n=1934) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 176 (47%) | 882 (45%) | 0.605 |

| Age (yrs, mean±SD) | 60 ± 9.5 | 60±9.4 | 0.981 |

| Race | 0.102 | ||

| Hispanic | 142 (38%) | 812 (42%) | |

| African American | 153 (41%) | 677 (35%) | |

| Others | 79 (21%) | 445 (23%) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Diabetes | 138 (36%) | 669 (34%) | 0.392 |

| Hypertension | 240 (64%) | 1194 (62%) | 0.383 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 166 (44%) | 778 (40%) | 0.134 |

| Smoking | 181 (48%) | 939 (49%) | 0.956 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg, mean±SD) | 143±27.7 | 141±28.6 | 0.214 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg, mean±SD) | 77±18.2 | 75±18.6 | 0.340 |

| Heart rate (bpm, mean±SD) | 84±21.4 | 83±21.2 | 0.559 |

| LVEF (%, mean±SD) | 47±12.0 | 48±12.3 | 0.741 |

| PASP (mmHg, mean±SD) | 45±9.5 | 40±9.0 | <0.001* |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean±SD) | 27.±5.7 | 34±5.9 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.37±1.0 | 1.31±1.1 | 0.327 |

| CKD | 59 (16%) | 251 (13%) | 0.146 |

| Sleep apnea | 110 (29%) | 515 (27%) | 0.268 |

| CAD | 157 (42%) | 693 (36%) | 0.024* |

| Cocaine use | 136 (36%) | 376 (19%) | <0.001* |

| HCV | 49 (13%) | 135 (7%) | <0.001* |

| HBV | 31(8%) | 116 (6%) | 0.096 |

| HF subtypes | 0.469 | ||

| HFrEF | 171 (46%) | 941 (48%) | |

| HFbEF | 39 (10%) | 172 (8.8%) | |

| HFpEF | 164 (44%) | 821 (42%) | |

| Ischemic HF | 157 (42%) | 693 (36%) | 0.024* |

| ICD parameters | |||

| Single chamber ICD | 27 (7%) | 119 (6%) | |

| Dual chamber ICD | 23 6%) | 113 (5.8%) | 0.856 |

| CRT-D | 9 (2.4%) | 35 (1.8%) | |

| Primary prevention | 46 (12%) | 189 (10%) | 0.308 |

| Secondary prevention | 13 (3.5%) | 78 (4%) | |

| HIV parameters | |||

| CD4 count cells/mm3 (mean±SD) | 368±245 | ||

| VL<200 copies/mL | 235 (63%) | ||

| ART therapy | 343 (92%) | ||

| Duration of therapy (yrs), median (IQR) | 9 (4–16) | ||

| Duration of HIV (yrs), median (IQR) | 9 (4–16) | ||

| Medications | |||

| Beta blocker | 322 (86%) | 1718 (88%) | 0.131 |

| ACE/ARB | 320 (86%) | 1706 (88%) | 0.152 |

| Spironolactone | 38 (10%) | 222 (11%) | 0.460 |

| Furosemide | 289 (77%) | 1545 (80%) | 0.252 |

BMI= body mass index, LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction, PASP= pulmonary artery systolic pressure, CKD= chronic kidney disease (eGFR <60) CAD= coronary artery disease, ICD= implantable cardioverter defibrillator, HCV- hepatitis C virus infection, HBV= hepatitis B virus infection, ACE I= angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB= angiotensin receptor blocker, ART = antiretroviral therapy. VL= viral load.

Groups were also separated according to the LVEF; there were 1,112 individuals with HFrEF (171 PLHIV, 941 non-HIV), 985 with HFpEF (164 PLHIV, 821, non-HIV), and 211 individuals with HFbEF (39 PLHIV, 172 non-HIV, Figure 1).

Outcomes

The median follow-up duration was 19 months (IQR 3, 24). Among the entire cohort, 35% were re-admitted with decompensated HF within 30 days of discharge from the incident HF hospitalization.

Primary outcome-30-day readmission due to HF:

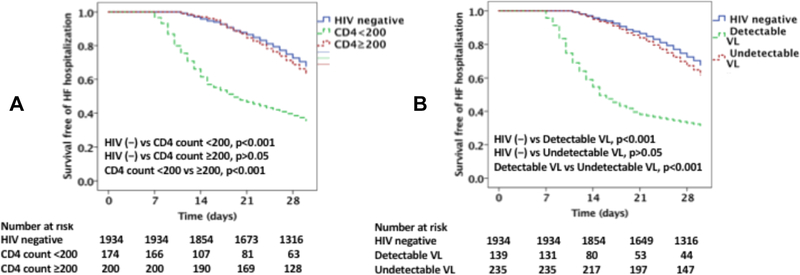

The 30-day HF hospital readmission rate was higher among PLHIV vs. non-HIV-infected individuals (49 vs 32%, p<0.001; Figure 2A & 2B). Among PLHIV, those with a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 had a higher 30-day HF readmission rate as compared to those with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 (64 vs 36%, p< 0.001; Figure 2A). Similarly, among PLHIV those with detectable viral load (≥200 copies/ml) had a higher 30-day readmission rate as compared with those with suppressed viral load (68 vs. 37%, p<0.001; Figure 2B). The 30-day readmission rate among PLHIV with HF with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (36 vs 32%, p=0.24; Figure 2A). Similarly, the 30-day readmission rate among PLHIV with HF with an undetectable VL did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (37 vs 32%, p=0.10; Figure 2B).

Figure 2 legend:

Kaplan Meier survival curves comparing 30-day readmission among (A) PLHIV with CD4 count <200 cells /mm3 and ≥200 cells /mm3 with uninfected controls, (B) PLHIV with detectable and undetectable viral load with uninfected controls.

However, when a CD4 count of ≥500 cells/mm3 was used as a threshold, there was no significant difference in 30-day HF readmission rate between PLHIV with a CD4 of ≥500 cells/mm3 and non-HIV infected individuals (34% vs 32%, p>0.05).

Among PLHIV, factors associated 30-day readmission due to HF on univariate analysis included: traditional CV risk factors (such as diabetes, history of CAD, smoking, cocaine use, elevated PASP) and HIV parameters (such as low CD4 count and high VL) (Supplemental Table 1). In a multivariable model, after adjusting for age, gender, cardiac risk factors, HF medications, and HIV parameters, the following parameters remained independently associated with 30-day readmission rate: smoking, history of CAD, cocaine use, elevated PASP, and low CD4 count (or high VL) (Table 2, Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2:

Multivariate analysis PLHIV with HF (30-day readmission outcome):

| Coveriates | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| H/o CAD | 1.714 | 1.332 | 2.473 | <0.001 |

| Cocaine | 1.433 | 1.202 | 2.313 | 0.002 |

| ICD firing | 1.523 | 1.071 | 2.221 | 0.004 |

| History of CVA | 1.248 | 0.976 | 2.764 | 0.134 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.343 | 1.021 | 2.621 | 0.021 |

| PASP | 1.141 | 1.125 | 1.457 | <0.001 |

| CD4 count | 0.992 | 0.987 | 0.999 | <0.001 |

Cox proportional hazard regression for multivariate analysis after adjusting for age, gender cardiac risk factors, HF medications and HIV parameters. Both viral load and CD4 count were not included in the multivariate model together due to the overlap between those individuals with a low CD4 count and a high (VL). VL was included in the multivariate model Supplemental Table1.

PLHIV with HFrEF:

The 30-day hospital readmission rate was higher among PLHIV with HFrEF vs. non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (52 vs 31%, p<0.001). Among PLHIV with HFrEF, those with a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 had a higher 30-day HF readmission rate as compared to those with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 (69 vs 40%, p<0.001). Similarly, among PLHIV those with detectable VL (≥200 copies/ml) had a higher 30-day readmission rate as compared with those with suppressed VL (70 vs. 37%, p<0.001). The 30-day readmission rate among PLHIV with HFrEF with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HFrEF (40 vs 31%, p=0.19). Similarly, the 30-day readmission rate among PLHIV with HFrEF with an undetectable VL did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HFrEF (37 vs 31%, p=0.21). Factors associated with re-hospitalization among PLHIV with HFrEF were similar to the entire cohort and are in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

PLHIV with HFpEF:

Parallel findings were noted among HFpEF. Specifically, the 30-day hospital readmission rate was higher among PLHIV with HFpEF vs. non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (44 vs 33%, p=0.006). Among PLHIV, those with a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 had a higher 30-day HF readmission rate as compared to those with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 (56 vs 34%, p=0.005). Similarly, among PLHIV those with detectable VL (≥200 copies/ml) had a higher 30-day readmission rate as compared with those with suppressed VL (62 vs. 35%, p<0.001). However, the 30-day readmission rate among PLHIV with HFpEF with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HFpEF (34 vs 33%, p=0.80). Similarly, the 30-day readmission rate among PLHIV with HFrEF with an undetectable VL did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HFpEF (35 vs 33%, p=0.64). Factors associated with rehospitalization among PLHIV with HFpEF were similar to the entire cohort and are in Supplemental Table 5 and 6.

PLHIV with HFbEF:

Identical findings were observed among the PLHIV with HFbEF. The 30-day hospital readmission rate was higher among PLHIV with HFbEF vs. non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (53 vs 33%, p=0.01) with a similar effect of CD4 count and VL (data not shown). Factors associated with re-hospitalization among PLHIV with HFbEF were similar to the entire cohort (Supplemental Tables 7 and 8).

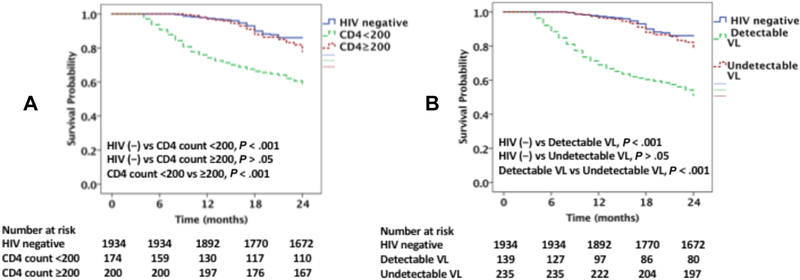

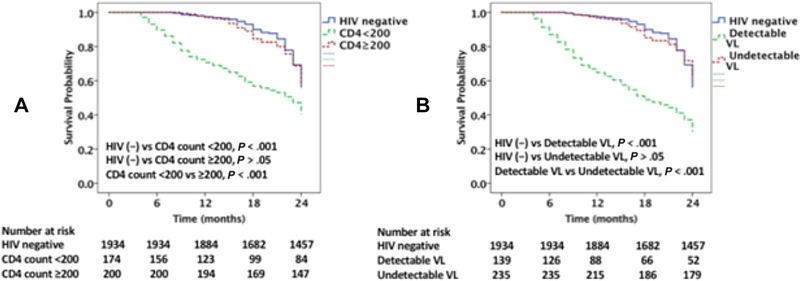

Secondary outcomes-CV and all-cause mortality:

Among the PLHIV admitted for decompensated HF (374 patients), there were 97 (26%) CV deaths and 143 (38%) all-cause deaths over two-years of follow up. There were 11 (3%) deaths with an unknown cause. The CV and all-cause mortality rates were significantly higher among PLHIV with HF vs. non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 26 vs 13.5% and allcause mortality; 38 vs 22%, p<0.001 for both) (Figures 3A, 3B & 4A & 4B). Among PLHIV, those with a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 had a higher CV and all-cause mortality rates as compared to those with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 (CV mortality; 37 vs 16.5% and all-cause mortality; 52 vs 27%, p< 0.001 for both) (Figures 3A & 4A). Similarly, among PLHIV those with detectable VL had higher CV and all-cause mortality rates as compared with those with suppressed VL (CV mortality; 48 vs. 17% and all-cause mortality; 64 vs 26%, p<0.001 for both; Figures 3B & 4B). However, the CV mortality and all-cause mortality rates among PLHIV with HF with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 did not differ significantly from the rates among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 16.5 vs 13.5%, p=0.249 and all-cause mortality; 27 vs 22%, p=0.14) (Figures 3A & 4A). Similarly, the CV mortality and all-cause mortality rates among PLHIV with HF with an undetectable VL did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 17 vs. 13%, p=0.15, and all-cause mortality; 26 vs 22%, p=0.66; Figures 3B & 4B).

Figure 3 legend:

Kaplan Meier survival curves comparing CV mortality among (A) PLHIV with CD4 count <200 cells /mm3 and ≥200 cells /mm3 with uninfected controls, (B) PLHIV with detectable and undetectable viral load with uninfected controls.

Figure 4 legend:

Kaplan Meier survival curves comparing all-cause mortality among (A) PLHIV with CD4 count <200 cells /mm3 and ≥200 cells /mm3 with uninfected controls, (B) PLHIV with detectable and undetectable viral load with uninfected controls.

However, there was no significant difference in CV mortality as well as all-cause mortality between PLHIV with HFrEF with a CD4 count ≥500 cells/mm3 vs non-HIV infected individuals with HF (CV mortality, 14.5 % vs 13.5%; all-cause mortality, 24% vs 22%, p>0.05 for both).

PLHIV with HFrEF:

Among the patients admitted for HFrEF (n=1,112), the CV and all-cause mortality rates were significantly higher among PLHIV with HFrEF vs. non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 28 vs 15% and all-cause mortality; 41 vs 26%, p<0.001 for both). Among PLHIV, those with a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 had a higher CV and all-cause mortality rates as compared to those with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 (CV mortality; 38 vs 19%, p=0.006 and all-cause mortality; 54 vs 26%, p<0.001). Similarly, among PLHIV those with detectable VL had higher CV and all-cause mortality rates as compared with those with suppressed VL (CV mortality; 47 vs. 16%, p=0.02 and all-cause mortality; 65 vs 29%, p<0.001). However, the CV mortality and all-cause mortality rates among PLHIV with HFrEF with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 did not differ significantly from the rates among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 19 vs 15%, p=0.33 and all-cause mortality; 29 vs 26%, p=0.56). Similarly, the CV mortality and all-cause mortality rates among PLHIV with HF with an undetectable VL did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 16 vs 15%, p=0.86 and all-cause mortality; 29 vs 26%, p=0.52).

PLHIV with HFpEF:

Among the patients admitted for HFpEF (n=985), the CV and all-cause mortality rates were significantly higher among PLHIV with HF vs. non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 24 vs 12% and all-cause mortality; 36 vs 18%, p<0.001 for both). Among PLHIV, those with a CD4 count of <200 cells/mm3 had a higher CV and all-cause mortality rates as compared to those with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 (CV mortality; 33 vs 17%, p=0.01 and all-cause mortality; 48 vs 26%, p= 0.004). Similarly, among PLHIV those with detectable VL had higher CV and all-cause mortality rates as compared with those with suppressed VL (CV mortality; 42 vs. 14%, p<0.001 and all-cause mortality; 58 vs 24%, p<0.001). However, the CV mortality and all-cause mortality rates among PLHIV with HF with a CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 did not differ significantly from the rates among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 17 vs 12%, p=0.56 and all-cause mortality; 26 vs 18%, p=0·08). Similarly, the CV mortality and all-cause mortality rates among PLHIV with HF with an undetectable VL did not differ significantly from the rate among non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 18 vs 12%, p=0.17 and all-cause mortality; 24 vs 18%, p=0.14).

PLHIV with HFbEF:

Among the patients admitted for HFbEF (n=221), the CV and all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher among PLHIV with HF vs. non-HIV-infected individuals with HF (CV mortality; 24 vs 12% and all-cause mortality; 36 vs 18%, p<0.001 for both) with a similar effect of CD4 count and VL (data not shown).

Discussion

The present analysis reveals that PLHIV with HF at a US urban tertiary care medical center have a markedly increased 30-day HF readmission rate and increased rates of CV and all-cause mortality as compared with individuals without HIV with HF. Among PLHIV, those with a detectable VL (preserved CD4) had a higher HF readmission and higher CV mortality; PLHIV with an undetectable VL had a similar 30-day HF readmission rate and CV mortality to uninfected controls with HF and as with uninfected HF patients. Additionally, among PLHIV, smoking, cocaine use, and HIV-specific parameters were predictors of HF readmission. Similar outcomes were observed regardless of the type of HF.

The present study reveals that the 30-day readmission as well as CV and all-cause mortality risks are increased among PLHIV compared to the ones without HIV. These findings with respect to increased CV and all-cause mortality rates among PLHIV with HF (including preserved as well as reduced ejection fraction) expand upon previous findings by Freiberg et al. based out of the US Veterans Aging Cohort Study-Virtual Cohort (VACS-VC) cohort (~97% male) suggesting that individuals with HIV and HF face increased mortality as compared with non-HIV-infected individuals with HF 4 especially those with a detectable VL/lower CD4 count. HIV is associated with increased CV mortality because of traditional CV risk factors, residual virally mediated inflammation despite of HIV treatment, side effects of ART 8, 14–17. In the same cohort, we have previously shown that PLHIV who are prescribed protease inhibitors are associated with significantly increased CV mortality compared to the PLHIV who were prescribed a non-protease inhibitor ART regimen 8. In another study, our group has also demonstrated that PLHIV with an ICD have a higher rate of ICD firing and subsequently an increased risk of CV mortality compared to the non-HIV individuals 14. Therefore, from the previous results, it may be plausible that the poor HF outcomes among PLHIV are multifactorial, contributed by different elements.

In our cohort of PLHIV with HF, CD4 count and VL were risk factors for adverse outcomes among patients with all types of HF. Specifically, PLHIV with HF with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 had worse outcomes (30-day HF readmission, CV mortality, and all-cause mortality) as compared with those with CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 a low CD4 count/high VL independently related to poor outcome (increased 30-day HF readmission rate) even after controlling for major traditional and non-traditional HF risk factors. We found similar results when stratifying the PLHIV as ≥ or <500 cells/mm3. Furthermore, the adverse outcomes were further decreased with CD4 count ≥ 500 cells/mm3. Several studies suggest that less well-controlled HIV is associated with an increased CV risk. Observationally, immune suppression and detectable viremia have been associated with incident myocardial infarction 18 and other vascular events among PLHIV 19. In the seminal SMART study, individuals with HIV randomized to intermittent ART had a trend towards increased rates of CV events compared to individuals with HIV randomized to continuous ART 20. In the SMART study, CV events included non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), non-fatal stroke, coronary artery disease requiring PCI or CABG, and death from CVD but did not include HF. Our study provides complementary observational support for a protective effect of immune recovery and viral suppression against HF and HF outcomes. Specifically, this study suggests that effective ART (with immunologic rebound and suppressed viremia) may partially protect PLHIV against adverse outcomes associated with HF. The mechanism involved in the increased rates of adverse HF in HIV, and the protective effect of a suppressed VL and higher CD4 count, are incompletely understood but may be explained by activation of immune system and persistent inflammation associated with HIV, which have been associated with an elevated HF risk 17. Moreover, these findings are also consistent with studies in the pre-ART phase in which HIV viremia perhaps via direct infection of cardiomyocytes or cardiac autoantibodies resulted in a cardiomyopathy 21–23.

In our study, amongst those individuals with HF, the group with HIV had a higher prevalence of cocaine use and a higher PASP as compared with the non-HIV-infected group. By contrast, the two groups did not differ significantly with respect to age, sex, race, ethnicity, and prevalence of numerous traditional HF risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cigarette smoking. Both cocaine use and higher PASP/pulmonary HTN predicted adverse outcomes. Cocaine use is known to be increased among PLHIV in the US 24. In the general population, cocaine use is a known cause of pulmonary HTN 25, which may be expected to contribute to the development and progression of HF 26–28. Among individuals with HIV, cocaine use has been associated with coronary artery disease (e.g. calcified plaque) 29 and with structural heart disease (e.g. myocardial fibrosis) 30. Previous studies have also shown an increased prevalence of pulmonary HTN among individuals with vs. without HIV 27 and have shown an association between even borderline elevations in PASP and hospitalization/mortality 26. Future studies are needed to assess whether measures to reduce cocaine use may represent yet another avenue for preventing adverse outcomes among PLHIV with HF.

The present investigation examines in a contemporary US-based population whether outcomes differ among individuals with and without known HIV with HF. There are some data from other studies to support these findings. Specifically, results from prognostic models involving more than 1000 patients enrolled in the THESUS-HF, a prospective registry of patients admitted with HF in 9 sub-Saharan African Countries, revealed an association between the presence of HIV with 180-days all-cause mortality 31. We extended these findings and extracted from the medical records detailed phenotypic data on traditional CVD risk factors, nontraditional CVD risk factors, CV parameters (LVEF, PASP), and HIV-specific parameters. Those with and without HIV were similarly distributed in terms of age, sex, race and prevalence of traditional CV risk factors. This helps us to isolate the potential contribution of HIV to risk of adverse outcomes, and indeed, our analyses suggest that uncontrolled HIV infection is particularly relevant. Our modeling for factors related to 30-day HF readmission rate also highlights potential avenues for clinical interventions (linkage to HIV care, substance abuse recovery programs) and highlights that factors important to HIV care may also impact HF outcomes.

Potential limitations of our study are as follows: First, as this is a retrospective cohort study based out of a single US urban tertiary care center and data may not be widely generalizable to PLHIV with HF in other regions. There are no data characterizing 30-day HF readmission among PLHIV; however, there are data on the 30-day HF re-admission rates among presumed HIV-uninfected patients with HF 32. In a large contemporary study involving 1,430,030 patients with HF, Krumholz et al. found that the 30-day HF re-admission rate ranged from 16—35% 33. This 30-day readmission rate in broad populations is similar to the rate of 30% in our cohort without HIV. An additional important point is that a relatively large proportion of our cohort had CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (47%) or VL >200 copies/ml (37%) despite an ART prescription rate of over 90%. Therefore, a potential explanation for the worse outcomes among PLHIV is poor adherence to treatment for either HIV or HF, as both, and in combination, are associated with a significant pill burden. In this retrospective study, adherence could not be assessed. However, we did test whether other surrogates of adherence were different between cases and controls. In patients with HF who do not take HF medications, both heart rate and blood pressure are increased. In our study cohort, there was no difference between the blood pressure and heart rate between the PLHIV and non-HIV controls suggesting that adherence with HF medications may be similar between groups. Advances in therapies for HIV, such as the use of integrase inhibitors as well as fixed-dose combination pills, may be associated with better medication adherence as well as more favorable metabolic effects and ultimately better outcomes. Additionally, prospective studies are needed in populations with HIV and HF where factors such as cocaine use are less common. In this study, the group without known HIV did not have confirmatory HIV testing. However, the potential inclusion of some individuals with HIV in the “non-HIV-infected” analytic group would have been expected to decrease the magnitude/significance of our primary findings. An additional limitation is that the readmission and CV mortality data from other institutions as well as the duration of hospitalization was not available. However, in our previously published data, we found that women living with HIV admitted for HF had a higher length of hospitalization compared to the non-HIV women with HF 6. Data were obtained from EHR; therefore, an important limitation is our dependency on documentation as well as unavailability of some data. For example, the mode of cocaine use was not available and the prevalence of cocaine use may have been significantly underestimated.

In conclusion, our work is the first to examine in a contemporary US-based population whether outcomes differ among individuals with and without known HIV with HF. Further, we carefully explored the potential effects of traditional HF risk factors, non-traditional HF risk factors, and HIV-specific parameters on adverse outcomes among PLHIV with HF, identifying an important potential contribution of HIV disease parameters as novel HF risk factors. Understanding how HIV status and HIV disease stage influences the development of HF and its outcomes is of critical public health importance to the population aging with HIV worldwide. Previous studies have shown that risk of HFpEF and HFrEF are increased in HIV. This study advances our understanding of HF progression in HIV, illustrating that critical outcomes (rates of 30-day HF readmission, CV mortality, and all-cause mortality) are worse among individuals with a low CD4 count or non-suppressed viral load.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health / National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute [5T32HL076136 to R.A.], [1R01HL137562 – 01A1to M.Z. and T.N], [1R01HL132786 – 01A1 to V.T.], [1R01HL130539–01A1, and K24HL113128–06 to T.N.], A. Curtis Greer, JD, Pamela Kohlberg and the Kohlberg Foundation, an American Heart Association Fellow to Faculty Award [12FTF12060588 to T.N.], National Institutes of Health/ Harvard Center for AIDS Research [P30- AI060354 to A.N. M.Z and T.N.], International Maternal Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Network Early Investigator Award [UM1AI068632 to A.N.], and the Nutrition Obesity Research Center at Harvard [P30-DK040561 to M.Z.].

Abbreviations:

- PLHIV

Persons living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- CV

Cardiovascular

- VL

Viral load

- HFrEF

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- HFpEF

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFbEF

Heart failure with borderline ejection fraction

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors do not have any commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lohse N, Obel N. Update of Survival for Persons With HIV Infection in Denmark. Ann Intern Med 2016;165(10):749–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, Modur SP, Althoff KN, Buchacz K, Burchell AN, Cohen M, Gebo KA, Gill MJ, Justice A, Kirk G, Klein MB, Korthuis PT, Martin J, Napravnik S, Rourke SB, Sterling TR, Silverberg MJ, Deeks S, Jacobson LP, Bosch RJ, Kitahata MM, Goedert JJ, Moore R, Gange SJ, North American ACCoR, Design of Ie DEA. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One 2013;8(12):e81355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO HIV Statsitics: http://www.who.int/hiv/data/en/. In; 2016.

- 4.Freiberg MS, Chang CH, Skanderson M, Patterson OV, DuVall SL, Brandt CA, So-Armah KA, Vasan RS, Oursler KA, Gottdiener J, Gottlieb S, Leaf D, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Tracy RP, Gibert CL, Rimland D, Bedimo RJ, Brown ST, Goetz MB, Warner A, Crothers K, Tindle HA, Alcorn C, Bachmann JM, Justice AC, Butt AA. Association Between HIV Infection and the Risk of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Antiretroviral Therapy Era: Results From the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2(5):536–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butt AA, Chang CC, Kuller L, Goetz MB, Leaf D, Rimland D, Gibert CL, Oursler KK, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Lim J, Kazis LE, Gottlieb S, Justice AC, Freiberg MS. Risk of heart failure with human immunodeficiency virus in the absence of prior diagnosis of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 2011;171(8):737–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janjua SA, Triant VA, Addison D, Szilveszter B, Regan S, Staziaki PV, Grinspoon SA, Hoffmann U, Zanni MV, Neilan TG. HIV Infection and Heart Failure Outcomes in Women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69(1):107–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, Chaitman BR, Cutlip DE, Farb A, Fonarow GC, Jacobs JP, Jaff MR, Lichtman JH, Limacher MC, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, Nissen SE, Smith EE, Targum SL. 2014 ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular Endpoint Events in Clinical Trials: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66(4):403–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvi RM, Neilan AM, Tariq N, Awadalla M, Afshar M, Banerji D, Rokicki A, Mulligan C, Triant VA, Zanni MV, Neilan TG. Protease Inhibitors and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With HIV and Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(5):518–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Authors/Task Force M, Document R. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European journal of heart failure 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, Serebruany V, Valgimigli M, Vranckx P, Taggart D, Sabik JF, Cutlip DE, Krucoff MW, Ohman EM, Steg PG, White H. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation 2011;123(23):2736–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addison D, Farhad H, Shah RV, Mayrhofer T, Abbasi SA, John RM, Michaud GF, Jerosch-Herold M, Hoffmann U, Stevenson WG, Kwong RY, Neilan TG. Effect of Late Gadolinium Enhancement on the Recovery of Left Ventricular Systolic Function After Pulmonary Vein Isolation. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neilan TG, Farhad H, Mayrhofer T, Shah RV, Dodson JA, Abbasi SA, Danik SB, Verdini DJ, Tokuda M, Tedrow UB, Jerosch-Herold M, Hoffmann U, Ghoshhajra BB, Stevenson WG, Kwong RY. Late gadolinium enhancement among survivors of sudden cardiac arrest. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8(4):414–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23(7):685–713; quiz 786–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvi RM, Neilan AM, Tariq N, Awadalla M, Rokicki A, Hassan M, Afshar M, Mulligan C, Triant VA, Zanni MV, Neilan TG. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator discharge among people living with HIV. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7(18):e009857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arzamendi D, Benito B, Tizon-Marcos H, Flores J, Tanguay JF, Ly H, Doucet S, Leduc L, Leung TK, Campuzano O, Iglesias A, Talajic M, Brugada R. Increase in sudden death from coronary artery disease in young adults. Am Heart J 2011;161(3):574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, Butt AA, Bidwell Goetz M, Leaf D, Oursler KA, Rimland D, Rodriguez Barradas M, Brown S, Gibert C, McGinnis K, Crothers K, Sico J, Crane H, Warner A, Gottlieb S, Gottdiener J, Tracy RP, Budoff M, Watson C, Armah KA, Doebler D, Bryant K, Justice AC. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(8):614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deeks SG, Tracy R, Douek DC. Systemic effects of inflammation on health during chronic HIV infection. Immunity 2013;39(4):633–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Triant VA, Regan S, Lee H, Sax PE, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of immunologic and virologic factors with myocardial infarction rates in a US healthcare system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55(5):615–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chow FC, Regan S, Feske S, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK, Triant VA. Comparison of ischemic stroke incidence in HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected patients in a US health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60(4):351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips AN, Carr A, Neuhaus J, Visnegarwala F, Prineas R, Burman WJ, Williams I, Drummond F, Duprez D, Belloso WH, Goebel FD, Grund B, Hatzakis A, Vera J, Lundgren JD. Interruption of antiretroviral therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease in persons with HIV-1 infection: exploratory analyses from the SMART trial. Antivir Ther 2008;13(2):177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Currie PF, Goldman JH, Caforio AL, Jacob AJ, Baig MK, Brettle RP, Haven AJ, Boon NA, McKenna WJ. Cardiac autoimmunity in HIV related heart muscle disease. Heart 1998;79(6):599–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiala M, Popik W, Qiao JH, Lossinsky AS, Alce T, Tran K, Yang W, Roos KP, Arthos J. HIV-1 induces cardiomyopathyby cardiomyocyte invasion and gp120, Tat, and cytokine apoptotic signaling. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2004;4(2):97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes de Campos WR, Chirwa N, London G, Rotherham LS, Morris L, Mayosi BM, Khati M. HIV-1 subtype C unproductively infects human cardiomyocytes in vitro and induces apoptosis mitigated by an anti-Gp120 aptamer. PLoS One 2014;9(10):e110930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dash S, Balasubramaniam M, Villalta F, Dash C, Pandhare J. Impact of cocaine abuse on HIV pathogenesis. Front Microbiol 2015;6:1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsue PY, Deeks SG, Farah HH, Palav S, Ahmed SY, Schnell A, Ellman AB, Huang L, Dollard SC, Martin JN. Role of HIV and human herpesvirus-8 infection in pulmonary arterial hypertension. AIDS (London, England) 2008;22(7):825–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maron BA, Hess E, Maddox TM, Opotowsky AR, Tedford RJ, Lahm T, Joynt KE, Kass DJ, Stephens T, Stanislawski MA, Swenson ER, Goldstein RH, Leopold JA, Zamanian RT, Elwing JM, Plomondon ME, Grunwald GK, Baron AE, Rumsfeld JS, Choudhary G. Association of Borderline Pulmonary Hypertension With Mortality and Hospitalization in a Large Patient Cohort: Insights From the Veterans Affairs Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking Program. Circulation 2016;133(13):1240–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Secemsky EA, Scherzer R, Nitta E, Wu AH, Lange DC, Deeks SG, Martin JN, Snider J, Ganz P, Hsue PY. Novel Biomarkers of Cardiac Stress, Cardiovascular Dysfunction, and Outcomes in HIV-Infected Individuals. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3(8):591–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guazzi M, Borlaug BA. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease. Circulation 2012;126(8):975–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai S, Fishman EK, Lai H, Moore R, Cofrancesco J Jr., Pannu H, Tong W, Du J, Barlett J. Long-term cocaine use and antiretroviral therapy are associated with silent coronary artery disease in African Americans with HIV infection who have no cardiovascular symptoms. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46(4):600–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai S, Gerstenblith G, Li J, Zhu H, Bluemke DA, Liu CY, Zimmerman SL, Chen S, Lai H, Treisman G. Chronic cocaine use and its association with myocardial steatosis evaluated by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in African Americans. J Addict Med 2015;9(1):31–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sliwa K, Davison BA, Mayosi BM, Damasceno A, Sani M, Ogah OS, Mondo C, Ojji D, Dzudie A, Kouam Kouam C, Suliman A, Schrueder N, Yonga G, Ba SA, Maru F, Alemayehu B, Edwards C, Cotter G. Readmission and death after an acute heart failure event: predictors and outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: results from the THESUS-HF registry. Eur Heart J 2013;34(40):3151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connor CM. High Heart Failure Readmission Rates: Is It the Health System's Fault? JACC Heart Fail 2017;5(5):393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan PS, Chen J, Ross JS, Drye EE, Bernheim SM, Wang Y, Bradley EH, Han LF, Normand SL. Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309(6):587–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.