Abstract

Scrapie is a mammalian transmissible spongiform encephalopathy or prion disease that predominantly affects sheep and goats. Scrapie has been shown to overcome the species barrier via experimental infection of other rodents. To confirm the re-transmissibility of the mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain to ovine prion protein (PrP) transgenic mice, mice of an ovinized transgenic mouse line carrying the Suffolk sheep PrP gene that contained the A136 R154 Q171/ARQ allele were intracerebrally inoculated with brain homogenates obtained from terminally ill ME7-infected C57BL/6J mice. Herein, we report that the mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain was successfully re-transmitted to the transgenic mice expressing ovine PrP. In addition, we observed changes in the incubation period, glycoform profile, and pattern of scrapie PrP (PrPSc) deposition in the affected brains. PrPSc deposition in the hippocampal region of the brain of 2nd-passaged ovine PrP transgenic mice was accompanied by plaque formation. These results reveal that the mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain has the capacity to act as a template for the conversion of ovine normal monomeric precursors into a pathogenic form in ovine PrP transgenic mice. The change in glycoform pattern and the deposition of plaques in the hippocampal region of the brain of the 2nd-passaged PrP transgenic mice are most likely cellular PrP species dependent rather than being ME7 scrapie strain encoded.

Keywords: Prion, prion diseases, scrapie, gliosis, amyloid plaque

INTRODUCTION

Scrapie, a transmissible neurodegenerative disease in sheep and goats, is the oldest known animal prion disease [1]. There are many strains of scrapie, distinguishable by their disease characteristics with each strain known to exhibit tropism targeting specific brain regions. The ME7 scrapie strain was originally isolated from a scrapie-infected sheep in the Suffolk sheep flock of the Moredun Research Institute in the UK [2]. The mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain serially passaged in C57BL/6J mice induces neurodegeneration and gliosis in the hippocampal brain region of infected animals. Proteinase K (PK) resistant scrapie prion protein (PrPSc) is readily detected in the late stage of scrapie and is widespread throughout the hippocampus [3]. Furthermore, ME7-infected animals have been shown to display marked vacuolation of the hippocampal, septal, and thalamic neuropils.

In the present study, we aimed to confirm the re-transmissibility of the mouse-adapted ME7 strain to ovine prion protein (PrP) transgenic mice and to describe the changes that might accompany the re-transmission. We report that interspecies transmission of the mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain to transgenic mice expressing ovine PrP was successful and it was accompanied by biophysical (glycoform pattern change) and neuropathological (PrPSc deposition with plaque formation) changes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and scrapie infectious agent inoculation

The ovinized transgenic mouse line carrying the Suffolk sheep PrP gene (TgSShpPrP) containing a Kozak ribosome-binding sequence was generated [4] and kindly provided by Dr. Richard I. Carp (New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, USA). The C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (USA). The prion strain ME7 was a gift from Alan Dickson (Neuropathogenesis Unit, UK) and was maintained by serial intracerebral passage of brain homogenates from terminally affected mice. ME7-infected brain tissues at the terminal stage of the disease were homogenized in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) under aseptic conditions using a sterile disposable instrument (Precision tissue grinder system, USA). Six-week-old female TgSShpPrP mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and inoculated with 30 µL of 1% (w/v) brain homogenates through an intracerebral route. Control inoculum was prepared from the brain of uninfected TgSShpPrP mice. Post-inoculation, the mice were observed daily until neurologic symptoms developed. Animals were sacrificed when ataxia, altered gait, hind limb weakness, and leg-clasping reflex were noticed. Brains of both control and infected mice were harvested for protein assay and histological pathology of prion disease. All animal experiments were approved by the Hallym Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (HMC-2018-0-0521-7), Korea. The procedures were conducted in a manner that minimized animal suffering and the number of animals used.

Western blot analysis

ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mouse brains were homogenized with 10% volumes of radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche, Germany). The brain homogenates were centrifuged at 13,500 r/min for 15 min at 4°C. Aliquots of supernatant frozen at −70°C were used for western blotting. Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To detect PrPSc, 7µg/mL of PK was treated for 1 h at 37°C. Equal amounts of protein (20 µg) were heated to 95°C for 5 min before being loaded into each lane in 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel with a loading buffer containing 0.125M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, 5% SDS, 10% mercaptoethanol, and 0.002% bromophenol blue. The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, USA) using an electrophoretic transfer system (BioRad, USA) at 90 V for 2 h. The membranes were washed with a Tris-buffered saline solution (pH 7.6) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) and then blocked in TBST containing 5% skim milk (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) for 60 min at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated at 4°C overnight with one of the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-PrP antibody (7A12, 1:5000), rabbit polyclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (1:10000, Dako, Denmark), mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN antibody (1:1000, Millipore, USA). After washing in TBST, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies against mouse and rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 1 h at room temperature and washed in TBST again. The target signals were visualized using digital images captured with an Image Quant TM LAS 4000 imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, USA) and an enhanced chemiluminescence western blot detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Western blot analysis (n = 3 for each group) was performed at least three times.

For peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) treatment, brain preparations were treated with 0.5 µg/mL of PK for 1 h prior to PNGase F treatment. PNGase treatment was performed using a PNGase F enzyme kit (P0704S; New England BioLabs, USA) as recommended by the supplier. Reaction mixtures were precipitated with 1:1 methanol/acetone overnight at −20 °C and centrifuged at 14,000 r/min for 1 h. The obtained pellets were then subjected to immunoblotting.

Immunohistochemistry

To detect PrPSc, immunohistochemical analyses were performed using an ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, USA) according to a modified avidin-biotin-peroxidase method [5]. Briefly, 5-μm thick paraffin-blocked brain sections were deparaffinized with xylene, hydrated in a graded ethanol series, and then treated with 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0, 0.5% Tween 20) for an antigen retrieval reaction in a microwave oven (LG Electronics, Korea) for 15 min. To stain the PrP, 10 µg/mL of PK were treated for 7 min at room temperature. After three washes in PBS, the tissue slides were treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxidase in methyl alcohol for 30 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity at room temperature. Non-specific sites were blocked with blocking buffer (10% normal goat serum, 0.1% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Tissue slides were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-PrP antibody 3F10 (1:100) [5]. After rinsing with PBS, tissue slides were treated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500) at room temperature for 1 h and avidin-biotin-peroxidase complexes (Vector Laboratories) and developed with a diaminobenzidine (DAB)-hydrogen peroxide solution (0.0005% DAB and 0.03% hydrogen peroxide in 50 mM Tris buffer). Next, the tissue sections were counterstained with Harris Hematoxylin solution, Gill No. 3 (Sigma, USA) and examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX51; Olympus, Japan). For immunofluorescence staining, brain sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN antibody (1:200, Millipore) and rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP antibody (1:200, Dako). Sections were subsequently visualized with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated and 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, USA). Fluorescence images were obtained under a confocal laser staining microscope using Zen software (LSM-700; Carl Zeiss, Germany). In addition, double-labeling was performed to examine the distributions of neurons and astrocytes.

Semi-quantitative grading for lesion profile

Semi-quantitative vacuolar degeneration grading was performed in nine standard sites of each mouse brain by applying previously established methods [6]. Briefly, areas of vacuolar degeneration in mouse brain tissue sections were counted under a light microscope (BX51, 100 × magnifications; Olympus). Three tissue sections from each of the three tissue blocks for each mouse were used for lesion counting. The scoring system assessed the number and size of vacuolar changes and was expressed by the following scale: 0, no vacuolation; 1, a few vacuoles widely and unevenly scattered; 2, a few vacuoles evenly scattered; 3, a moderate number of vacuoles evenly scattered; and 4, marked vacuolation [7].

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean values. Differences between two groups were compared by using two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests. Statistical significance was defined as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

RESULTS

Serial transmission of mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strains to TgSShpPrP mice

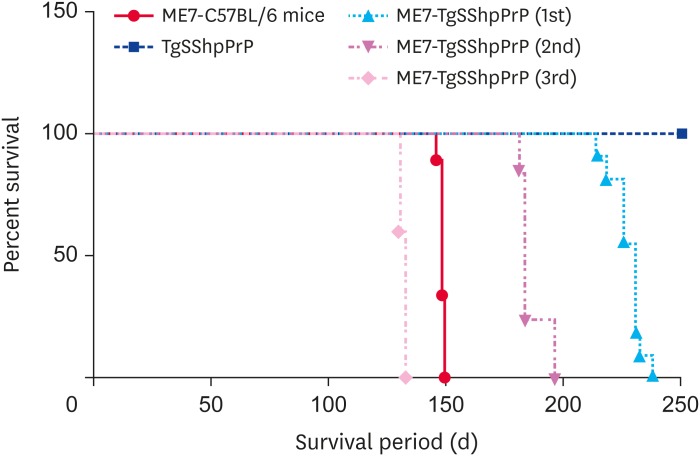

Intracerebral inoculation of the mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain to transgenic mice expressing ovine PrP resulted in prion diseases with distinct clinical manifestations. In this study, the incubation period for ME7-infected C57BL/6J mice was 148.0 ± 1.19 days while that of ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice at first passage was 227.0 ± 6.35 days, with reductions to 185.3 ± 5.41 days and 132 ± 1.55 days at 2nd and 3rd passages, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Survival curve of TgSShpPrP mice. Comparative survival days of TgSShpPrP mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain at 1st, 2nd, and 3rd passages. The abscissa shows the survival days and the y-axis shows the percentages of survival. The average survival days and number of animals used are as follows: ME7-C57BL/6J, 148 ± 1.19 (n = 9); ME7-TgSShpPrP (1st), 227 ± 6.35 (n = 13); ME7-TgSShpPrP (2nd), 185 ± 5.41(n = 11); ME7-TgSShpPrP (3rd), 132 ± 1.55 (n = 5).

PrP, prion protein; TgSShpPrP, transgenic mouse line carrying the Suffolk sheep PrP gene.

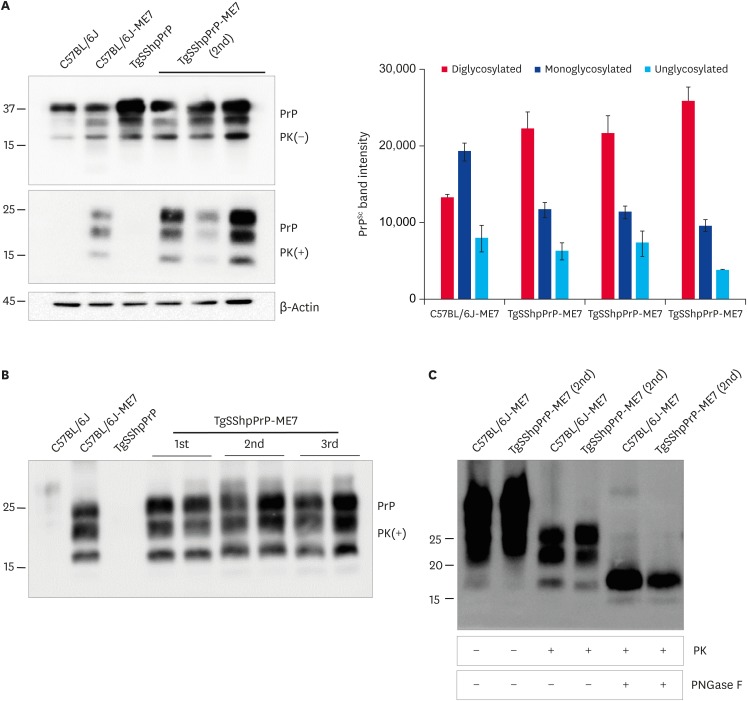

Differential glycoform patterns of the abnormal PrP in the brains of C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice infected with ME7 scrapie strain

We analyzed brain tissues from ME7-infected C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice to determine if distinct abnormal PrP profiles capable of differentiating the disease phenotypes in the two species of mice could be identified. Immunoblotting was done using PK enzyme-treated brain homogenates obtained from control, C57BL/6J-ME7, and TgSShpPrP-ME7 mice. We expected that the PrPSc glycoform pattern in C57BL/6J-ME7 mice would be the same as that for TgSShpPrP-ME7 mice, especially when the ratios of the three PrPSc protein bands were compared. For ME7-infected C57BL/6J mice, the strongest PrPSc signal was observed in the mono-glycosylated band. However, for ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice, the strongest PrPSc signal was observed in the di-glycosylated band (Fig. 2A). Similar glycoform patterns were observed from the first to the third passage (Fig. 2B). There was no difference between the electrophoretic mobilities of C57BL/6J-ME7 and TgSShpPrP-ME7 mice, although the C57BL/6J-ME7 pattern appeared to contain a greater amount of resistant PrPSc species after PNGase F treatment than that from TgSShpPrP-ME7 mice (Fig. 2C). The difference in glycoform patterns in the two mouse strains suggests that interspecies transmission of the infectious agent can result in a different glycoform characteristic in the new host.

Fig. 2. Abnormal PrP detection in ME7-infected C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice. (A) Western blot analysis for PrPc and PrPSc in ME7-infected mice at 2nd passage. 20 μg of total protein were loaded into each well. For PrPSc detection, the brain homogenates were digested with 7 µg/mL of PK. PrPc and PrPSc were detected using mAb 7A12. Relative densities of un-, mono-, and di-glycosylated forms of PrPSc obtained from ME7-infected mice obtained using image J analyzer. (B) Western blot analysis for PrPc and PrPSc in ME7-infected mice at 1st, 2nd, and 3rd passages. Total protein (20 μg) was loaded into each well. In order to detect PrPSc, the brain homogenates were digested with 7 µg/mL of PK. The PrPc and PrPSc were detected using mAb 7A12. (C) To confirm the electrophoretic mobility of PrPSc from ME7-infected C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice, brain homogenates were treated with PK and PNGase F prior to western blotting with mAb 7A12.

PrP, prion protein; TgSShpPrP, transgenic mouse line carrying the Suffolk sheep PrP gene; PrPc, cellular PrP; PrPSc, scrapie PrP; PK, proteinase K; PNGase F, peptide N-glycosidase F.

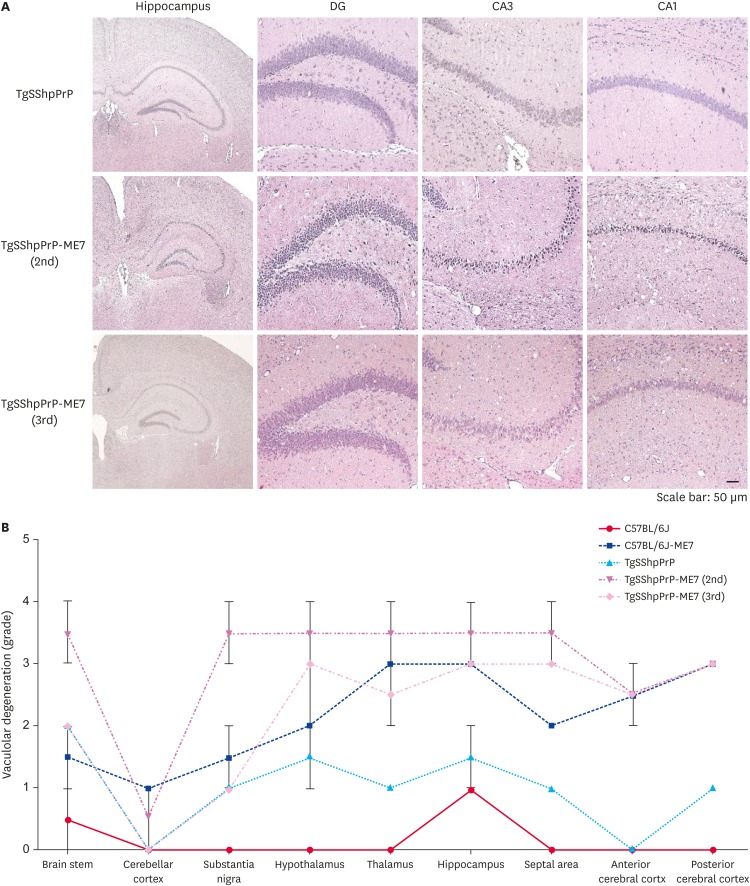

Spongiform degeneration in the hippocampal region of ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice

Spongiform degeneration is known to be one of the hallmarks of neurodegeneration in prion disease [8]. To examine the extent of spongiform degeneration in ME7-infected TgSShpPrP brain tissue, using immunohistochemistry staining, hippocampal regions of control and infected mice brains were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. We observed an increase in spongiform degeneration in the dentate gyrus, cornu ammonis 3 (CA3) and CA1 hippocampal regions of infected mouse brains compared to that in the control mice brains (Fig. 3A). In prion diseases, the brain region profile is influenced by the prion's ‘strain properties,’ which indicate the invasion route to the brain [8]. We analyzed the histopathological alteration induced by the ME7 scrapie strain in the whole brain regions of TgSShpPrP mice. Nine regions of non-inoculated and ME7-inoculated TgSShpPrP mice brains were scored. The lesion scores of the ME7-inoculated TgSShpPrP mice were higher at both 2nd and 3rd passages than those of non-inoculated mice in most brain areas, with the exception of the cerebellar cortex (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. H&E staining and severity of neurodegeneration associated vacuolation in TgSShpPrP-ME7 infected brains. (A) H&E staining of age-matched control TgSShpPrP and terminally ill ME7-infected mice showing the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 regions of the hippocampus. The hippocampus was viewed at a low magnification (4×); all other regions were viewed at a higher magnification (40×). (B) Mean vacuolation scores and standard errors of the means from brains of ME7-infected C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice and age-matched control mice.

PrP, prion protein; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; TgSShpPrP, transgenic mouse line carrying the Suffolk sheep PrP gene; DG, dentate gyrus; CA, cornu ammonis.

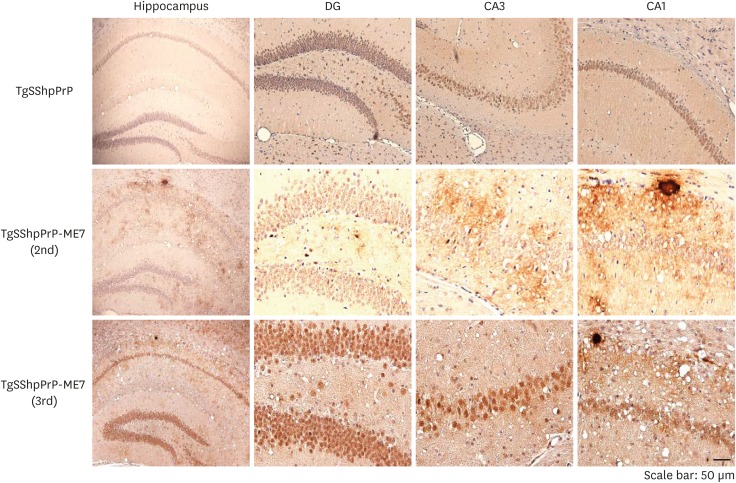

PrPSc detection in the hippocampal region of ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice

To determine the localization and distribution of PrPSc in ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice, aggregation and tissue deposition of PrPSc were observed in the area of the hippocampus. The most conspicuous feature of the PrPSc staining in ME7-infected TgSShpPrP brain was the heavy deposits of PrP plaques, which were mainly located in the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 hippocampal regions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. PrPSc Immunostaining in the hippocampus of ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice. PrPSc deposition in the DG, CA3, and CA1 hippocampal regions of age-matched control mice and ME7-infected mice (2nd and 3rd passages) were evaluated by using 3F10 anti-prion antibody. Plaques of an amyloid nature and plaque-like deposits (aggregated PrPSc) were observed in the ME7-infected brain regions. The hippocampus was viewed at a low magnification (4×); all other regions were viewed at higher magnification (40×).

PrP, prion protein; PrPSc, scrapie PrP; TgSShpPrP, transgenic mouse line carrying the Suffolk sheep PrP gene; DG, dentate gyrus; CA, cornu ammonis.

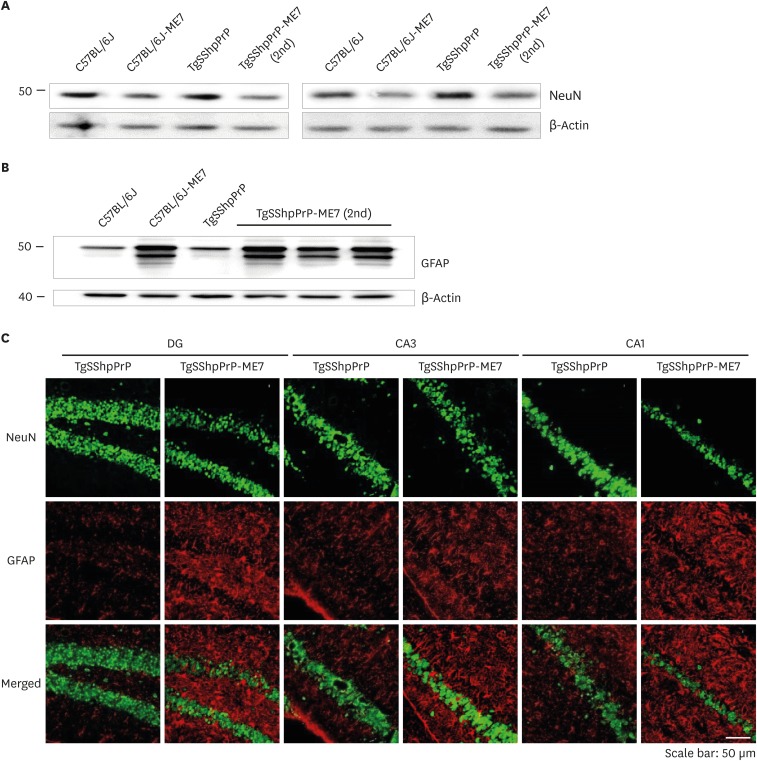

Extent of neuronal loss and activation of reactive astrocytes in ME7-infected C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice

Notable features of prion diseases include activated astrogliosis and microglial and neuronal loss, and these neuropathological features are associated with the accumulation of a conformationally altered PrPSc isoform. We observed decreases in the expression level of NeuN in ME7-infected C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice when compared to that of age-matched non-infected mice (Fig. 5A and C). However, ME7-infected mice brain showed increased expression of GFAP relative to that in non-infected mice (Fig. 5B and C). Immunohistochemical staining results indicated that GFAP immunoreactivity was higher in ME7-infected brains.

Fig. 5. Loss of neurons and activation of reactive astrocytes in ME7-infected C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP mice at 2nd passage. Presence of GFAP indicating astrogliosis and loss of neurons were examined by immunoblotting (A, B) and immunostaining (C) using anti-GFAP and anti-NeuN in C57BL/6J and TgSShpPrP age-matched control mice and mice inoculated with ME7 strain (2nd passage). Both western blot and immunohistochemical results revealed increased expression of GFAP protein and decreased expression level of NeuN in ME7-infected mice relative to the expressions in the control mice.

PrP, prion protein; TgSShpPrP, transgenic mouse line carrying the Suffolk sheep PrP gene; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; DG, dentate gyrus; CA, cornu ammonis.

DISCUSSION

Scrapie can be experimentally induced in one species by transmission from another species. Interspecies transmission, when successful, results in prolonged incubation periods in the new host. This phenomenon, also known as a transmissibility barrier, has been shown to be abrogated with adaptation of the strain to the new host after 2–3 passages [9,10,11,12]. In this study, the transmissibility of a long-time mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain to TgSShpPrP mice was examined. We observed reductions in incubation time from 227.0 ± 6.35 days at first passage to 185.3 ± 5.41 days at second passage and 132 ± 1.55 days at 3rd passage. Consistent with our result is the report that cross-species transmission leads to an inefficient disease process resulting in long incubation time at first passage but becomes shortened after the prion becomes adapted to the new host. This is probably because there is increased efficiency of propagation of the donor PrPSc and the experimentally induced scrapie at second passage as it becomes more adapted to the environment of the recipient host [13,14,15].

The glycosylation profile is one of the biochemical features used to discriminate scrapie strains. Results from our study indicate a change in glycoform patterns; the PrPSc from ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice brains were predominantly di-glycosylated in contrast to the mono-glycosylated band pattern observed in ME7-infected C57BL/6J mice brains. Similar to our results are those reported by Shi et al. [1]. Similar glycosylation patterns observed at the third passage suggests that the glycosylation profile formed during interspecies transmission can be maintained over serial passaging in the same host [16]. This may also support the suggestion that the brain microenvironment of a new host can have a profound effect on PrPSc properties following interspecies transmission.

To determine the neuropathological changes induced by the interspecies transmission in this study, H&E staining was performed on formalin-fixed tissues of ME-7-infected TgSShpPrP and control mice. The dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 hippocampal regions were examined for spongiform degeneration. Our results showed that sponge-like lesions were more pronounced in the CA1 regions of the terminally ill ME7-infected TgSShpPrP mice examined. Numerous oval shaped vacuoles were observed in the fields of view, most particularly in the CA1 hippocampal region of the infected brains. Another criterion employed for determining strain peculiarity is the vacuolar lesion profile. Severe vacuolation was observed in the hippocampal, brain stem, and substantia nigra regions of infected mouse brains. Other grey matter areas such as hypothalamus, thalamus, and septal area also showed marked vacuolation but there was less conspicuous vacuolation in the cerebellar cortex, which is in agreement with results from a similar study report by Cunningham et al. [17]. Reports from other experimental studies have revealed that the pattern of PrPSc deposition across brains of infected mice is agent strain dependent [18,19,20]. In this study, we detected PrPSc accumulation and the formation of plaques, and PrPSc aggregation accompanied by plaques was more prominent in the CA1 hippocampal region. Sisó et al. [21] reported that amyloid plaques are abundant and characteristics of murine 87V infection, but they inconsistently occur in ME7 and 22A infections, whereas vacuolar plaques are sometimes observed in ME7 infections of VRQ/VRQ Cheviot and ARQ/ARQ Suffolk sheep. In addition, Cunningham et al. [17] reported that ME7-infected brains showed a greater amount of the PrPSc punctuate labeling pattern with some small plaque depositions in both the hippocampal and thalamic brain regions. A strong counterstain is a well-known marker of sick cells about to die via an apoptotic pathway [22,23]. Our results showed a decreased population of neuronal cells and a significant high accumulation of hematoxylin-counterstaining. Also, there was a decrease in the expression level of a neuronal marker used to measure the extent of neuronal loss between infected and control mice. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuronal loss has been reported to be significant in ME7- and 79A-infected mice [17,24,25,26]. Most likely, the severe aggregation of PrPSc in CA1 in this study resulted from the death of CA1 neurons. The increase in the population of reactive astrocytes was well pronounced in brain tissues of the ME7-infected mice. Furthermore, GFAP upregulation was marked in the dentate gyrus of the brain, which is consistent with similar findings reported by Hilton et al. [25]. They demonstrated that the hippocampus and dentate gyrus are sites of GFAP upregulation in ME7- and 79A-infected animals.

Differences in pathological features such as the patterns of histological lesions and PrPSc accumulations in scrapie-infected mice have been reported to represent the total interaction between the host (genotype, age, sex, and breed) and the agent strain (passage history, dose, route of inoculation, donor genotype, and organ used for preparing inoculum) [6,27,28]. In addition, it has been suggested that some disease phenotype features might be strain-specific and propagated in the recipient host [21].

In conclusion, interspecies transmission of a long-term mouse-adapted ME7 scrapie strain was successful in transgenic mice expressing ovine PrP and the infection was accompanied by biophysical and neuropathological changes in the recipient host. The differences in survival time, biophysical (glycoform change), and neuropathological features (plaque formation) reported in this study are most likely species dependent rather than strain encoded.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by Korea Health Technology R & D through The Korean Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant Number: HII6C0965).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Kim YS.

- Data curation: Babalola JA, Kim JM.

- Formal analysis: Babalola JA, Kim JM, Lee YJ, Park JH, Choi HS, Choi YG

- Supervision: Kim YS, Choi EK, Kim JM.

- Writing - original draft: Babalola JA.

- Writing - review & editing: Babalola JA, Kim JM, Lee YJ, Park JH, Choi HS, Choi YG, Choi EK, Kim YS.

References

- 1.Shi Q, Zhang BY, Gao C, Zhang J, Jiang HY, Chen C, Han J, Dong XP. Mouse-adapted scrapie strains 139A and ME7 overcome species barrier to induce experimental scrapie in hamsters and changed their pathogenic features. Virol J. 2012;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zlotnik I, Rennie JC. Further observations on the experimental transmission of scrapie from sheep and goats to laboratory mice. J Comp Pathol. 1963;73:150–162. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(63)80018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asuni AA, Gray B, Bailey J, Skipp P, Perry VH, O'Connor V. Analysis of the hippocampal proteome in ME7 prion disease reveals a predominant astrocytic signature and highlights the brain-restricted production of clusterin in chronic neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:4532–4545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.502690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubenstein R, Bulgin MS, Chang B, Sorensen-Melson S, Petersen RB, LaFauci G. PrP(Sc) detection and infectivity in semen from scrapie-infected sheep. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:1375–1383. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.038802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi JK, Park SJ, Jun YC, Oh JM, Jeong BH, Lee HP, Park SN, Carp RI, Kim YS. Generation of monoclonal antibody recognized by the GXXXG motif (glycine zipper) of prion protein. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2006;25:271–277. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2006.25.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser H. The pathology of natural and experimental scrapie. In: Kimberlin RH, editor. Slow Virus Diseases of Animals and Man. North-Holland, Amsterdam: 1976. pp. 267–303. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YS, Carp RI, Callahan S, Wisniewski HM. Incubation periods and histopathological changes in mice injected stereotaxically in different brain areas with the 87V scrapie strain. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;80:388–392. doi: 10.1007/BF00307692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragagnin A, Ezpeleta J, Guillemain A, Boudet-Devaud F, Haeberlé AM, Demais V, Vidal C, Demuth S, Béringue V, Kellermann O, Schneider B, Grant NJ, Bailly Y. Cerebellar compartmentation of prion pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 2018;28:240–263. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Béringue V, Vilotte JL, Laude H. Prion agent diversity and species barrier. Vet Res. 2008;39:47. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2008024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce ME, McBride PA, Jeffrey M, Scott JR. PrP in pathology and pathogenesis in scrapie-infected mice. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF02780660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson AG. Scrapie in sheep and goats. In: Kimberlin RH, editor. Slow Virus Diseases of Animals and Man. North-Holland, Amsterdam: 1976. pp. 209–239. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimberlin RH. Early events in the pathogenesis of scrapie in mice: biological and biochemical studies. In: Prusiner SB, Hadlow WJ, editors. Slow Transmissible Diseases of the Nervous System. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsh RF, Bessen RA, Lehmann S, Hartsough GR. Epidemiological and experimental studies on a new incident of transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:589–594. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Q, Xiao K, Zhang BY, Zhang XM, Chen LN, Chen C, Gao C, Dong XP. Successive passaging of the scrapie strains, ME7-ha and 139A-ha, generated by the interspecies transmission of mouse-adapted strains into hamsters markedly shortens the incubation times, but maintains their molecular and pathological properties. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:1138–1146. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor DM, Dickinson AG, Fraser H, Marsh RF. Evidence that transmissible mink encephalopathy agent is biologically inactive in mice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1986;12:207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1986.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck KE, Thorne L, Lockey R, Vickery CM, Terry LA, Bujdoso R, Spiropoulos J. Strain typing of classical scrapie by transgenic mouse bioassay using protein misfolding cyclic amplification to replace primary passage. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham C, Deacon RM, Chan K, Boche D, Rawlins JN, Perry VH. Neuropathologically distinct prion strains give rise to similar temporal profiles of behavioral deficits. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck KE, Sallis RE, Lockey R, Vickery CM, Béringue V, Laude H, Holder TM, Thorne L, Terry LA, Tout AC, Jayasena D, Griffiths PC, Cawthraw S, Ellis R, Balkema-Buschmann A, Groschup MH, Simmons MM, Spiropoulos J. Use of murine bioassay to resolve ovine transmissible spongiform encephalopathy cases showing a bovine spongiform encephalopathy molecular profile. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:265–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown DA, Bruce ME, Fraser JR. Comparison of the neuropathological characteristics of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) in mice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:262–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce ME, McConnell I, Fraser H, Dickinson AG. The disease characteristics of different strains of scrapie in Sinc congenic mouse lines: implications for the nature of the agent and host control of pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:595–603. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisó S, Chianini F, Eaton SL, Witz J, Hamilton S, Martin S, Finlayson J, Pang Y, Stewart P, Steele P, Dagleish MP, Goldmann W, Reid HW, Jeffrey M, González L. Disease phenotype in sheep after infection with cloned murine scrapie strains. Prion. 2012;6:174–183. doi: 10.4161/pri.18990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Sun J, Li Y. The neuroprotective effects of resveratrol preconditioning in transient global cerebral ischemia-reperfusion in mice. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26:550–555. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.14195-15.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma DR, Wani WY, Sunkaria A, Kandimalla RJ, Sharma RK, Verma D, Bal A, Gill KD. Quercetin attenuates neuronal death against aluminum-induced neurodegeneration in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2016;324:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham C, Deacon R, Wells H, Boche D, Waters S, Diniz CP, Scott H, Rawlins JN, Perry VH. Synaptic changes characterize early behavioural signs in the ME7 model of murine prion disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2147–2155. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilton KJ, Cunningham C, Reynolds RA, Perry VH. Early hippocampal synaptic loss precedes neuronal loss and associates with early behavioural deficits in three distinct strains of prion disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffrey M, Halliday WG, Bell J, Johnston AR, MacLeod NK, Ingham C, Sayers AR, Brown DA, Fraser JR. Synapse loss associated with abnormal PrP precedes neuronal degeneration in the scrapie-infected murine hippocampus. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26:41–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Béringue V, Herzog L, Jaumain E, Reine F, Sibille P, Le Dur A, Vilotte JL, Laude H. Facilitated cross-species transmission of prions in extraneural tissue. Science. 2012;335:472–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1215659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeffrey M, Begara-McGorum I, Clark S, Martin S, Clark J, Chaplin M, González L. Occurrence and distribution of infection-specific PrP in tissues of clinical scrapie cases and cull sheep from scrapie-affected farms in Shetland. J Comp Pathol. 2002;127:264–273. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2002.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]