Abstract

Ethnographic studies examining how women manage their sexual and reproductive health can inform strategies to address unmet needs, say Anita Hardon and colleagues

People often choose to manage their sexual and reproductive health outside health facilities, sometimes using modern medicines obtained from pharmacies, drug stores, and markets. Ethnographic studies of self care practices reveal opportunities to reduce unmet needs and advance human rights based approaches to sexual and reproductive health. We highlight findings from ethnographic studies that show how healthcare professionals could better meet the priorities of women and girls for improved sexual and reproductive health.

Anthropologists’ studies of self care

With rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases and chronic health problems associated with ageing populations, definitions of health are expanding to include capabilities to adapt and self manage.1 Public health initiatives increasingly promote healthy eating and exercise, and healthcare providers support patients to monitor and manage their health problems.

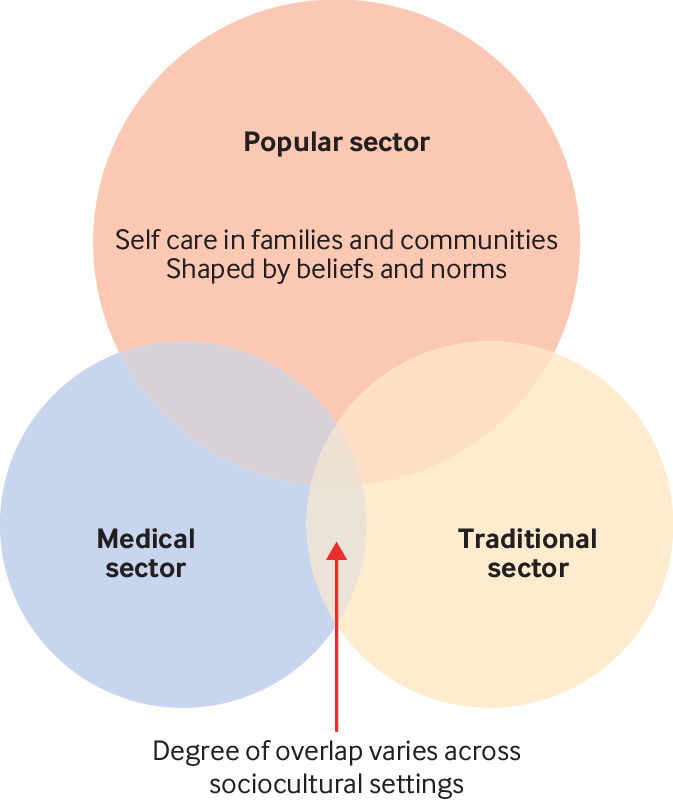

Medical anthropologists have long sought to understand factors influencing how people take care of themselves. In the 1980s, Kleinman’s influential book Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture 2 emphasised the importance of self care and its relation to the medical and traditional healthcare sectors (fig 1).

Fig 1.

Three sectors of healthcare adapted from Kleinman’s model

Following Kleinman, medical anthropologists have shown how self care involves treating everyday health problems at home and in communities with modern or neotraditional drugs (traditional medicines packaged as modern pharmaceuticals) obtained from pharmacies, stores, and markets.3 People are often influenced by health messages and apply medical or traditional treatments themselves, especially when they are constrained by costs or access to healthcare facilities.4 5 6 For example, in rural northeast Thailand, anthropologists found that 80% of self reported uterine complaints, such as vaginal discharge and pelvic pain, were self treated, often with small doses of antibiotics purchased from markets (eg, one to three pills) after advertising campaigns promoting branded tetracycline for these complaints.7 The Lao speaking Isaan villagers cited hard work, menstruation, and tiredness as the most important triggers of reproductive ill health and feared that recurrent uterine symptoms would progress to cervical cancer.7

A disproportionate burden of sexual and reproductive ill health falls on women and girls.8 Globally, almost all 4.3 billion people of reproductive age have inadequate sexual and reproductive health services; an estimated 200 million women report an unmet need for modern contraception; 45 million lack adequate antenatal care; and an estimated 266 000 women die each year from cervical cancer that could have been prevented through screening or vaccination.9

Health systems increasingly rely upon individuals, families, and communities to administer and manage many sexual and reproductive health interventions. Ethnographic studies, however, suggest that how and why people already engage in self care are often overlooked in the development of policies and programmes. This can lead to a mismatch between the care promoted by healthcare professionals and the self management that already takes place at home and in communities. They may therefore seek assistance elsewhere, risking suboptimal outcomes and high costs.

Female hygiene

A sizeable traditional and modern sanitation industry caters to women’s hygiene needs. In many countries, this includes a wide range of herbal and synthetic vaginal washes. Studies investigating use of herbal concoctions—jamu—in Indonesia have found that women feel a lifelong obligation to remain attractive to their partners. For example, brides are traditionally given a herbal wash to tighten their vaginas on their wedding day.10 The concoctions are made at home by women from locally available plants, such as turmeric, ginger, and betel leaves.

In Makassar, eastern Indonesia, vaginal washes that contain extract of betel leaves are among the most readily available female hygiene products. The slogan of the most popular brand, Resik-V, proclaims: “Fragrant and tight, especially for female areas.” When interviewed, women described Resik-V as cheap, convenient, and safe because it is for external use; they reported no negative effects and claimed the product cleans, tightens, and perfumes their vaginas.11 Using a vaginal wash was part of their daily routine.

Female sex workers also used it to avoid feeling “dirty” and because, in the era of HIV, having a clean, fragrant vagina was deemed necessary to attract customers.12 Influenced by unsubstantiated marketing claims about antiseptic properties, some young women believed vaginal washes protected against sexually transmitted infections.13

The popularity of vaginal washes and inserts for sexual health and pleasure extends beyond Asia to other regions, including sub-Saharan Africa. When microbicidal vaginal gels were developed to reduce HIV transmission, they were initially considered as products that women would use covertly, without their husbands and partners finding out.12 However, the acceptability research that accompanied clinical trials of microbicides found that topical gels were valued for their perceived effect on sexual pleasure and vaginal hygiene. Women did not keep the use of the gels secret, but rather talked about it with their sexual partners, who likewise appreciated the product.13

Secrecy and taboos are major concerns for girls menstruating for the first time. Girls are often unaware of the causes and have difficulty managing menstruation. For instance, schools in resource constrained settings lack running water and separate toilets for girls, and there are practical difficulties in disposing of or washing sanitary products.14 15 In India, girls in rural areas often have no access to commercial pads and so rely on reusable cloths, the use of which is associated with absence from school.16 Several sexual and reproductive health programmes are testing sanitary packages that encourage open communication in families and provide guidance on how to manage menstruation.14 Rural initiatives are also seeking to produce sanitary products locally.17

Fertility management

Since the 1970s, health policy makers worldwide have promoted the use of contraceptives such as hormonal pills, implants, injections, and intrauterine devices, to prevent unwanted pregnancy and to plan families. Barriers to contraceptive use include perceived side effects, religious opposition, and moralities limiting access for young women.18

When unwanted pregnancies occur, women turn to a various measures, often assisted by traditional midwives and using modern medicines. In the 1980s and 90s, anthropological studies found women were attempting to induce abortion by using drugs contraindicated during pregnancy, such as antimalarials19 and misoprostol, a prostaglandin on the market to treat ulcers.20

Although the use of misoprostol in medical abortions is well established, it is not licensed for this purpose. Studies have described its use without medical supervision by vulnerable women with unmet needs for contraceptive and abortion care, including those on low income, immigrants, refugees, and women who live in conflict settings.20 21 Faced with unintended pregnancy, women obtain information from their social networks or pharmacists on how to get the drug, often illegally.18 With incomplete information, women may ingest the incorrect dose,18 20 21 22 and the absence of quality post-abortion care results in many seeking help in the emergency department, where stigmatisation and discrimination from healthcare providers affect future care seeking behaviours.20

Designed to be used in exceptional cases, such as contraceptive failure or sexual assault,23 emergency hormonal contraceptives are also used by women to manage their fertility. In sub-Saharan Africa, women using emergency contraception describe it as the method most aligned with their contraceptive needs and report repeated, regular, or frequent (even weekly) use.23 Some sex workers use emergency contraception in combination with condoms as their regular form of protection in case condoms burst. Other women report using it in combination with the rhythm method during the fertile window.24

Infrequent and unplanned sex, combined with fears about side effects of other hormonal contraceptives, are reasons some women and girls opt for emergency contraceptives.25 In Ethiopia, emergency contraception is popular among young people because it can be purchased only when needed (fewer pills), allows for discreet use (users can take the pill and then throw away the box), and is believed to lack side effects and minimally affect future fertility.25 However, users and healthcare providers are often uncomfortable when buying or prescribing these drugs because of the taboos around premarital sex. Young people therefore rely on friends and partners, leaflets, and the internet for information and access to this product.26

In a Canadian study, women described misconceptions about how emergency contraception works and where to access it, and they reported judgmental attitudes by community members and healthcare providers.27 In response, researchers advocated a more women friendly approach to its provision—for example, supplying it to any woman presenting at any access point when she meets the medical criteria and providing pills in advance of need in case an emergency arises.27

Building on self care

Ethnographic studies on Kleinman’s three domains of sexual and reproductive health highlight how women use traditional and medical technologies to care for their sexual and reproductive health and how these may not align with what healthcare professionals, researchers, and policy makers expect. This research provides insights into women’s needs, concerns, desires, and lived realities, which can inform strategies to reduce unmet needs for contraception and to improve sexual and reproductive health.

The use of vaginal washes and inserts in Indonesia and elsewhere shows the importance of sexual pleasure and perceptions of cleanliness and suggests that in some settings secrecy is not necessarily women’s primary concern. Yet, when developing microbicides, researchers assumed that women would want to use the products without their sexual partners knowing. Although this may sometimes be the case, other factors, including augmenting sexual pleasure, can also have a role, and this was not initially reflected in the studies that evaluated the products’ prevention of HIV transmission.12

To promote the appropriate use of sexual and reproductive health technologies, women and girls also need discreetly delivered information that is easy to understand. For example, research on fertility regulation among young women in Ethiopia shows that emergency contraceptives constitute a “plan A”—not a “plan B”—mode of contraception.26 28 Alongside common information channels, such as posters placed in pharmacies and places where young people meet, Both25 suggests printing key messages (eg, instructions for use) on the blister package because most users discard the box and the leaflet shortly after purchase to ensure discretion and using mobiles phones, the internet, and social media to deliver information. Given that most women and girls purchase emergency contraception after weekends or holidays, campaigns could be targeted around these times. The information should emphasise that the pills do not protect against sexually transmitted infection, including HIV, and highlight other pertinent issues, such as efficacy, side effects, and consequences of repeated use.

With improved digital and health literacy, online and mobile information platforms can also support safe self care. In India and South Africa, abortion is legal and pills are provided in women’s programmes and health facilities. In these countries, text message services guide women and girls through self administering the sequence of pills: informing them about the effects they are likely to experience after taking the drugs and what they can do. For example: “Hi more info on the pills: if u get cramps, use heat or take painkillers. It can be pretty sore – don’t be scared. U may feel sick, vomit or get a runny tummy. It’s not a problem.”28 The evidence based text messages also ask users to check for bleeding and encourage them to use family planning in future.

Virtual communities can also provide opportunities for exchanging experiences, peer support, and counselling. In these communities, the division between lay and expert knowledge is increasingly blurred.26 29 Some online sites have found a balance between exchanging user experiences and the user sensitive provision of medical information (see for example www.healthtalk.org, which has a section for young people and sexual health). Such platforms can also provide information on the limitations and risks of self care technologies. Data protection and assurance of privacy in these platforms are key, especially in countries where sexual and reproductive health and rights are not protected and access to justice limited.

Building partnerships between user communities and health systems around self care technologies is a promising approach to ensure the safe and accelerated implementation of interventions. Aligned with such an approach, the WHO guideline on safe abortion care acknowledges women who self manage abortion as simultaneous healthcare providers and recipients.30 Another example includes marketing messages from sanitary product manufacturers aimed at legitimising family discussion of menstruation and engaging and educating girls while building their self esteem.31 There are opportunities for users and healthcare providers to work together to enhance self care technologies for sexual and reproductive health. Attention must, however, be paid to power differentials and divergent priorities. Ethnographic research has much to offer implementation design to meet the needs of women and girls and improve their sexual and reproductive health.

Key messages.

Self care for sexual and reproductive health entails both traditional and modern medicine

Understanding women’s and girls’ needs, concerns, and desires can help design self care technologies to reduce unmet needs

Novel strategies are needed to provide information, promote dialogue, and increase access to self care products and services

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Contributors and sources:AH drafted the first version of the manuscript. MN reviewed the draft and provided critical feedback. All other authors contributed to content and writing, read and approved the final manuscript. AH is the guarantor. This article draws on a literature review and expert meetings to inform WHO guideline on self care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the UNDP/UNFPA/Unicef/WHO/World Bank Special Programme for Human Reproduction (HRP) and commissioned by The BMJ. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication of these articles. Open access fees are funded by HRP.

References

- 1. Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343:d4163. 10.1136/bmj.d4163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture: An exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. Vol 3 Univ of California Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hardon A, Desclaux A, Egrot M, Simon E, Micollier E, Kyakuwa M. Alternative medicines for AIDS in resource-poor settings: insights from exploratory anthropological studies in Asia and Africa. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2008;4:16. 10.1186/1746-4269-4-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whyte SR, der Geest S, Hardon A. Social lives of medicines. Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haak H, Hardon AP. Indigenised pharmaceuticals in developing countries: widely used, widely neglected. Lancet 1988;2:620-1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90652-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bledsoe CH, Goubaud MF. The reinterpretation of Western pharmaceuticals among the Mende of Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med 1985;21:275-82. 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90101-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boonmongkon P, Nichter M, Pylypa J. Mot luuk problems in Northeast Thailand: why women’s own health concerns matter as much as disease rates. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:1095-112. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00404-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Narasimhan M, Pillay Y, García PJ, et al. Wilton Park Consultation Investing in sexual and reproductive health and rights of women and girls to reach HIV and UHC goals. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1058-9. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30316-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress-sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission. Lancet 2018;391:2642-92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Handayani L, Suparto H, Suprapto A. Traditional system of medicine in Indonesia. Tradit Med Asia. World Health Organization Geneva, 2001: 47. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hardon A Ilmi Idrus N. Magic power: changing gender dynamics and sex-enhancement practices among youths in Makassar, Indonesia. Anthropol Med 2015;22:49-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hardon A. The turn to female-controlled safe sex technologies. In: Manderson L, ed. Technologies of sexuality, identity and sexual health. Routledge, 2012: 71-88. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781136328787/chapters/10.4324%2F9780203121689-10. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Montgomery CM, Gafos M, Lees S, et al. MDP Team Re-framing microbicide acceptability: findings from the MDP301 trial. Cult Health Sex 2010;12:649-62. 10.1080/13691051003736261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chandra-Mouli V, Patel SV. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod Health 2017;14:30. 10.1186/s12978-017-0293-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumar A, Srivastava K. Cultural and social practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls. Soc Work Public Health 2011;26:594-604. 10.1080/19371918.2010.525144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Eijk AM, Sivakami M, Thakkar MB, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010290. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price A. Low cost feminine hygiene in rural India. 15 Mar 2014. http://www.ithinkwell.org/low-cost-feminine-hygiene-in-rural-india/

- 18. Taqueban EMM. A way out in Eden: maternal health crisis in Manila. Philipp Soc Sci Rev 2013;65(2). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van der Sijpt E. Ambiguous ambitions: on pathways, projects, and pregnancy interruptions in Cameroon. Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zordo SD. The biomedicalisation of illegal abortion: the double life of misoprostol in Brazil. Hist Cienc Saude Manguinhos 2016;23:19-36. 10.1590/S0104-59702016000100003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Daoud F, Foster AM. Navigating barriers to abortion access. In: Wynn L, ed. Abortion pills, test tube babies, and sex toys : emerging sexual and reproductive technologies in the Middle East and North Africa. 2017: 58-68. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hancart Petitet P. Abortion politics in Cambodia social history, local forms and transnational issues. Glob Public Health 2018;13:692-701. 10.1080/17441692.2017.1354228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Both R. Young people’s use and perceptions of emergency contraceptives in sub-saharan Africa: Existing insights and knowledge gaps. Sociol Compass 2013;7:751-61 10.1111/soc4.12066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Both R, Samuel F. Keeping silent about emergency contraceptives in Addis Ababa: a qualitative study among young people, service providers, and key stakeholders. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:134. 10.1186/s12905-014-0134-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Both R. Emergency contraceptive use in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: challenging common assumptions about young people’s contraceptive practices. Reprod Health Matters 2015;23:58-67. . 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hardon A, Idrus NI. On Coba and Cocok: youth-led drug-experimentation in Eastern Indonesia. Anthropol Med 2014;21:217-29. 10.1080/13648470.2014.927417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shoveller J, Chabot C, Soon JA, Levine M. Identifying barriers to emergency contraception use among young women from various sociocultural groups in British Columbia, Canada. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2007;39:13-20. 10.1363/3901307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Tolly KM, Constant D. Integrating mobile phones into medical abortion provision: intervention development, use, and lessons learned from a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014;2:e5. 10.2196/mhealth.3165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hardon A, Sanabria E. Fluid drugs: Revisiting the anthropology of pharmaceuticals. Annu Rev Anthropol 2017;46:117-32 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization Health worker role in providing safe abortion care and post abortion contraception. World Health Organization, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Always. Tips & advice: “the talk.” https://always.com/en-us/tips-and-advice/the-talk