Abstract

Manjulaa Narasimhan and colleagues argue that there is a pressing need for a clearer conceptualisation of self care to support health policy

Self care existed well before formal health systems and is an important contributor to health outcomes. For many people, self care within well established cultural and social norms may be the only healthcare they access. Where healthcare systems do exist, self care remains a crucial component for maintaining health. For example, brushing teeth is a daily self care practice in which individuals are in control of their dental health, but it can link to healthcare should check-ups or advanced interventions be needed. Moreover, interventions that were previously available only through facility based healthcare providers are now being accessed in the self care environment. Pregnancy tests, for instance, have transitioned to self care.

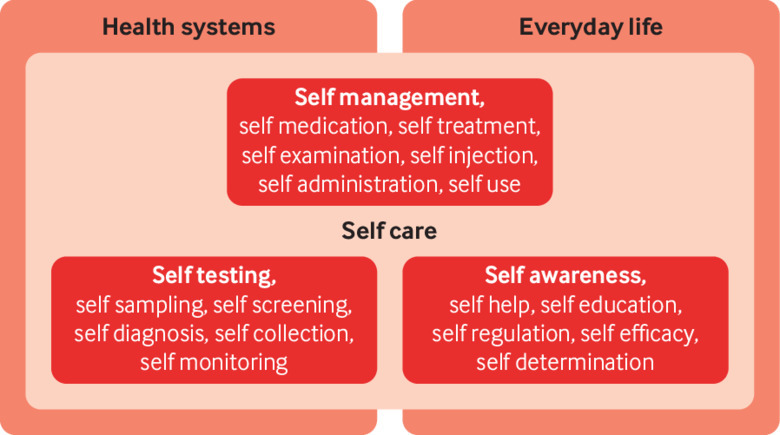

Self care interventions in the health sector have increased since the primary healthcare movement began,1 fuelled by an increased focus on empowering women,2 improving the intrinsic capacity of older people,3 and the role of self care in the management of chronic diseases, including mental health.4 The World Health Organization’s working definition of self care includes “the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health-care provider.”5 6 While this is a broad definition that includes many activities, it is important for health policy to recognise the importance of self care, especially where it intersects with health systems and health professionals (fig 1). The recent global conference on primary health care, which celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Alma Ata declaration, again underlined the importance of empowering and supporting people in acquiring the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to maintain their health or the health of those for whom they care.7

Fig 1.

Self care in the context of interventions linked to health systems

A growing globalised market of drugs, diagnostics, and devices, coupled with rapid advances in digital technologies, is making new configurations of self care possible. Many of these interventions will be regulated, but many more will not. Given the increasing number of new interventions, the importance of linkage to care, and the supportive part the health system can play, there is a pressing need for a clearer conceptualisation of self care to support health policy.

System and people centred framing of self care

Self care ranges from a set of activities to a set of capacities. It is possible to think about self care from two complementary perspectives, one focused on improving the capacity of individuals to self care and another focused on how self care relates to the health system: people centred and system centred.

The capacity and ability of an individual to make informed health decisions and make use of available health resources is an important component of effective prevention and management of a health condition. The ability to access and use societal and familial resources contributes to personal agency and autonomy and determines health outcomes. Seen thus, self care is about caring and the relational context, finding ways to enable good self care and avoid social and cultural iatrogenesis of self medicalisation.8 From this perspective, the capacity to meet physical, physiological, psychological, and self fulfilment needs is important.9

Given the potential to enhance health and wellbeing, self care is an important component of people centred care.6 A people centred framing emphasises psychological, empowerment, and self fulfilment needs,10 placing less emphasis on technical activities and instead looking at self care in terms of capacities, building on a person’s “health assets,” both as a condition for and a product of the practice of self care.11

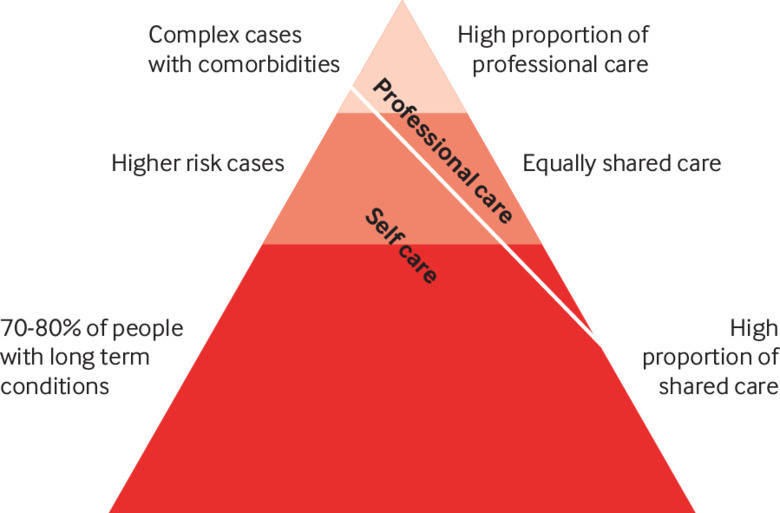

A complementary perspective on self care is a “system centred” framing, which focuses on activities that can add value in dealing with specific diseases or health issues that healthcare managers and policy makers consider important. The dominant paradigm from this perspective is summarised by a Kaiser Permanente pyramid12 that features self care as distinct from, but complementary to, professional healthcare (fig 2).12 From this perspective, the effect of self care on health outcomes and its division from professional care are key considerations. Promoting task shifting or sharing between professionals and the general public or optimising the linkage to professional care are priorities to harness self care to enhance specific health system outcomes.13 14 In this framing, the focus is on managing and mitigating health concerns or risk factors.

Fig 2.

Health systems perspective on the relation between self and professional care

Conceptual framework for self care

Individuals choose a self care health intervention for many positive reasons, including convenience, cost, empowerment, and a better fit with values or lifestyle. A proved efficacy and endorsement by the health system may be another reason to choose self care interventions.

Given that an ideal, well functioning health system is seldom a reality, particularly in resource constrained settings, individuals may also opt for self care interventions to avoid the health system owing to poor quality services or because information, interventions, or products are inappropriate, unaffordable, or inaccessible. Stigma from healthcare providers or from within families and communities may be another reason people turn to self care. Self care interventions fulfil a particularly important role in these situations, as the alternative might be no access at all to health promoting interventions.15

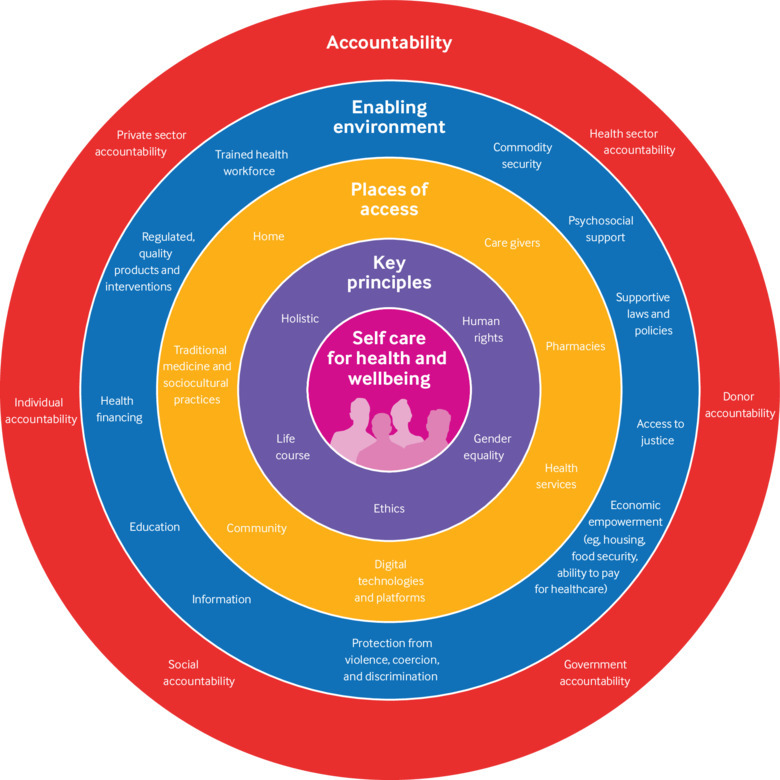

Challenges exist in mitigating the inherent risks in promoting self care, particularly in terms of ensuring safety and protecting people against unnecessary expenditure and harmful interventions. Just as high quality healthcare is important, high quality self care is too. We have developed a conceptual framework to support WHO normative guidance (fig 3). The aim of the framework is to support healthcare policy makers and implementers who are thinking through the complexity of promoting high quality self care for individuals. The framework aims to ensure that all individuals are considered, including those who may not be aware of their right to health and those who may fall through the cracks of the existing healthcare system.

Fig 3.

Framework for self care interventions

Naturally, given the importance of a people centred approach, self carers and care givers are at the centre of the framework that is focused on health and wellbeing. The key principles for promoting self resilience, autonomy, and agency in any health policy guidance for self care are recognising human rights, sex equality, and other ethical considerations. Two further key principles include taking a holistic approach to health and recognising that needs change across a person’s life course.

The conceptual framework recognises that in addition to the traditional self care practices that societies have passed on through generations, people are accessing new information, products, and interventions through stores, pharmacies, and the internet. Digital health and mobile technologies are increasing rapidly, not only as places of access but in many other aspects of self care.16

The next layer of the framework recognises that a supportive and safe enabling environment for the introduction of self care interventions is essential and that self care interventions should be implemented in the context of a supportive legal and policy environment. This means access to the following: justice; a strong, accountable, people centred healthcare system; integrated and accessible services of good quality; protection from violence, coercion, and discrimination; social inclusion and acceptance; and knowledge and information, appropriately tailored to different needs.

Individuals can be in control of some self care interventions, such as using condoms; while others, such as a positive HIV self test, will require confirmation within a healthcare setting; and others still, such as self sampling of HPV, will require the health setting to do the test. This dynamic interaction between individuals and the health system can also change over time in line with the needs and choices of individuals. The health system supporting people for self management of health conditions remains an integral part of self care.

Accountability for health outcomes is reflected at multiple levels in the conceptual framework, and accountability of the health sector remains a key factor in the equitable support to quality self care interventions. Meaningful community engagement where self care is championed and advocated by patient groups is also an essential factor in the success of linkage to care.

Self care for sexual and reproductive health and rights

While self care is important in all aspects of health, it is particularly important and challenging to manage for populations negatively affected by sex, political, cultural, and power dynamics. This is true for sexual reproductive health and rights, where many people are not able to have autonomy over their body or to make decisions around sexuality and reproduction. Safe linkage between self care and quality healthcare for vulnerable individuals is critically important to avoid harm. When self care is not a positive choice but born out of fear or because there is no alternative, it can increase vulnerabilities.

In a number of areas in sexual and reproductive health and rights, effective self care with safe links to healthcare has the potential to substantially improve health. These include self care interventions for fertility regulation (for example, pregnancy tests and17 contraception18); sexual health promotion (for example, seeking advice and information through digital health for sexually transmitted infections,19 virility enhancement,20 and alleviation of menopause symptoms21); disease prevention and control activities (for example, use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis22); and treatment (for example, self management of abortion23 and self administered HIV antiretroviral drugs in community based treatment clubs24).

Alongside these interventions, supportive approaches ensure equity and quality of self care—for example, in providing care to dependents, including differently abled, newborn, or young children; seeking medical assistance, including going to a health centre, counselling, and treatment; or for confirmatory testing (such as for a positive HPV test result).25

Reimagining healthcare delivery

WHO’s current strategic priorities are focused on the “triple billion” goals, which are for one billion more people to benefit from universal health coverage, one billion more people to be better protected from health emergencies, and one billion more people to enjoy better health and wellbeing. Achieving these goals will not be straightforward, but reorienting formal health systems to positively engage with self care could make a substantial contribution. WHO has begun developing consolidated people centred, evidence based normative guidance around self care to support these aims. This guideline will aim to advance universal health coverage without exposing individuals, families, and communities to financial hardship; reduce health inequities by tackling human rights, gender, ethical, legal, social, economic, and environmental determinants of health; and increase access to quality health information, interventions, products, and care in areas where the burden of disease and the scope for improved wellbeing is the greatest.

The development of this guidance entails broad, consultative processes across multiple sectors to consider the quality of evidence on health outcomes of self care interventions, a balance of benefits and harms, the acceptability of self care interventions to health workers and the populations that they serve, resources that enable self care, feasibility of making better links between self care and professional care, financial costs to vulnerable populations, and equity. The guidance will acknowledge that self care activities are undertaken by lay people on their own behalf, either alone or in collaboration with professionals,26 and that a solid evidence base, still largely to be constructed, requires further research.

Reimagining, reinvesting, and recommitting to healthcare that recognises the strengths of individuals, their families, communities, and social networks as active agents in their health and not merely passive recipients of health services can contribute to improving the health and wellbeing of even the most vulnerable populations. Although risk and benefit calculations may vary across settings and population groups, with appropriate guidance and an enabling environment, self care interventions offer an exciting way forward to reach a range of improved health outcomes.27

This is particularly relevant for sexual reproductive health and rights, where self care could improve awareness and decision making around sexuality and reproduction. Providing individuals with the capacity to access resources for effective, evidence based self care is a public good. It is an undervalued part of attempts to provide people with universal access to healthcare they need and responds to the autonomy and self reliance people value in their life. Developing normative guidance for policy makers, donors, and researchers will be essential to redraw the boundaries of a stronger healthcare system that includes self care.

Key messages.

Self care interventions increase choice, accessibility, and affordability, as well as opportunities for individuals to make informed decisions regarding their health and healthcare

Self care interventions may also exacerbate inequalities and therefore need to be monitored and, where appropriate, linked with health systems

Self care can be thought of using two complementary frames: people centred and system centred.

Normative guidance will be essential to redraw the boundaries of a stronger healthcare system that includes self care

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Norris, Christopher Pell, and Wim Van Lerberghe for their critical feedback. The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation and the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction provided financial support. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Health Organization.

Contributors and sources:MN is leading the WHO normative guideline development at WHO on self care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) . PA co-chaired the meeting on ethical, legal, human rights, and social accountability of self care for SRHR. AH co-chaired some of the scoping meetings, including the WHO expert meeting on self care interventions (15-16 March, 2018, Geneva, Switzerland), where some of the concepts in this article were developed. AH also co-chaired the guideline development group (GDG) meeting (14-16 January, 2019, Montreux, Switzerland). Both PA and AH are members of the guideline development group. MN wrote the first draft of the document, and all authors contributed extensively to its development and finalisation.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the UNDP/UNFPA/Unicef/WHO/World Bank Special Programme for Human Reproduction (HRP) and commissioned by The BMJ. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication of these articles. Open access fees are funded by HRP.

References

- 1.Declaration of Alma Ata. 1978. https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf

- 2.Murray M, Brady M, Drake J. Women’s self-care: products and practices. Outlook on Reproductive Health 2017 Nov. https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/RH_Outlook_Nov_2017.pdf

- 3. Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Slaets JPJ. How to understand and improve older people’s self-management of wellbeing. Eur J Ageing 2005;2:235-44. 10.1007/s10433-005-0012-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lucock M, Gillard S, Adams K, Simons L, White R, Edwards C. Self-care in mental health services: a narrative review. Health Soc Care Community 2011;19:602-16. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatch S, Kickbusch I, eds. WHO self help and health in Europe. New approaches in health care. WHO Regional Office for Europe, 1983.

- 6.World Health Organization. Self care for health: a handbook for community health workers and volunteers. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia, 2013. http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B5084.pdf

- 7.World Health Organization. Astana declaration on primary health care. 2018. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf

- 8. Dowrick C, Frances A. Medicalising unhappiness: new classification of depression risks more patients being put on drug treatment from which they will not benefit. BMJ 2013;347:f7140. 10.1136/bmj.f7140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Godfrey CM, Harrison MB, Lysaght R, Lamb M, Graham ID, Oakley P. Care of self —care by other—care of other: the meaning of self-care from research, practice, policy and industry perspectives. Int J Evidence-Based Healthcare 2011;9:3-24. 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2010.00196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization Package of essential noncommunicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings. World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brady M. Women’s self-care: a new take on an old practice. PATH, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health Services Management Centre Improving care for people with long-term conditions: A review of UK and international frameworks. NHS, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Logie C, Khoshnood K, Okumo M, et al. Self care interventions could advance sexual and reproductive health in humanitarian settings. BMJ 2018;365:l1083 10.1136/bmj.l1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification: supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization. Ethical, legal, human rights and social accountability of self-initiated interventions. Brocher Meeting report. WHO, 2018.

- 16.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for digital health interventions. WHO, 2016.

- 17. Robinson JH. Bringing the pregnancy test home from the hospital. Soc Stud Sci 2016;46:649-74. 10.1177/0306312716664599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hardon A. Women’s views and experiences of hormonal contraceptives: what we know and what we need to find out. beyond accept users’ perspect contracept. Reprod Health Matters 1997;:68-77 10.1016/S0968-8080(97)90087-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gkatzidou V, Hone K, Sutcliffe L, et al. User interface design for mobile-based sexual health interventions for young people: design recommendations from a qualitative study on an online Chlamydia clinical care pathway. BMC Med Inform Decis Making 2015;15:72. 10.1186/s12911-015-0197-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Both R. A matter of sexual confidence: young men’s non-prescription use of Viagra in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Cult Health Sex 2016;18:495-508. 10.1080/13691058.2015.1101489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thompson JJ, Ritenbaugh C, Nichter M. Why women choose compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: lessons from a qualitative study of menopausal decision-making. BMC Womens Health 2017;17:97. 10.1186/s12905-017-0449-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calabrese SK, Magnus M, Mayer KH, et al. Putting PrEP into practice: lessons learned from early-adopting US providers’ firsthand experiences providing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and associated care. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157324. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Webster N. Unsafe abortion: regulation of the social body even beyond time and space. Cult Health Sex 2013;15:358-71. 10.1080/13691058.2012.758313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Venables E, Edwards JK, Baert S, Etienne W, Khabala K, Bygrave H. “They just come, pick and go.” the acceptability of integrated medication adherence clubs for HIV and non communicable disease (NCD) patients in Kibera, Kenya. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164634. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Allen-Leigh B, Uribe-Zúñiga P, León-Maldonado L, et al. Barriers to HPV self-sampling and cytology among low-income indigenous women in rural areas of a middle-income setting: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 2017;17:734. 10.1186/s12885-017-3723-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Health education in self-care: possibilities and limitations. 1984. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70092

- 27. Narasimhan M, Kapila M. Implications of self-care for health service provision. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97:76-76A. 10.2471/BLT.18.228890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]