Abstract

Transport processes in cancer are the focus of transport oncophysics (TOP). In the TOP approach, the sequential negotiation of transport barriers is critical to both drug delivery and metastasis development. New and creative therapeutic opportunities are currently emerging, stimulated by the study of cancer hallmarks with the TOP approach.

In the past decade, a new perspective in cancer therapy has emerged that focuses on understanding the mechanisms and interplay of transport phenomena in the development and treatment of cancer: transport oncophysics (TOP; see Glossary) [1]. In this framework, the origin, characteristics, and development of cancer complexity are described and addressed in terms of biological transport barriers [2]. Exploiting these barriers guides the rational design of therapeutics with an unprecedented potential in cancer treatment [3,4].

For many years, genomics has been regarded as the panacea of cancer. However, far from its original promise of providing a definitive solution, the current unprecedented gene sequencing power has confirmed the need of a multidisciplinary approach to unravel the complexity and heterogeneity of cancer. Such variations across patients and within the same patient are the fundamental reason why genetic approaches to precision medicine fail [5]. Therefore, a complementary view has started to take root, in which physics is regarded as essential to understanding and unraveling the intricacy of cancer [6]. This very approach gave birth to TOP, which helps to rationalize and optimize drug delivery strategies to cancer lesions [1]. While TOP and other oncophysical new initiatives experienced slow reception, they started to be recognized a few decades ago, and the Physical Sciences-Oncology Network (PS-ON)i was established as part of the National Cancer Institute standard operations, encouraging deeper involvement of physical sciences in oncological research.

The Transport Oncophysics Perspective on Cancer Hallmarks

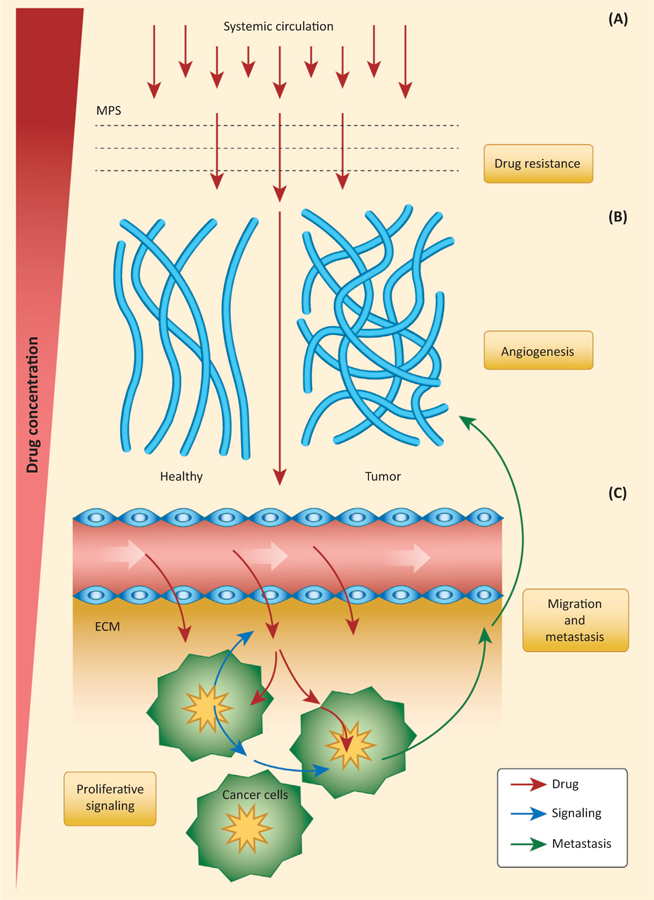

The TOP approach to view cancer can be correlated with the classical biological view pictured by Hanahan and Weinberg [7] (Figure 1). In their perspective, cancer is described in terms of biological hallmarks: sustained proliferative signaling, evasion of growth suppressors, avoidance of immune destruction, enabled replicative immortality, tumor-promoting inflammation, metastasis activation and invasion, angiogenesis induction, genome instability and mutation, resistance to cell death, and deregulation of cellular energetics. In the TOP view, therapeutic targeting of these hallmarks is approached in terms of transport barriers that hinder or control permeation of therapeutics and signaling substances across different tumor compartments [2]. These barriers impact transport from the systemic level to the local tumor microenvironment and cells. For example, at the systemic level, opsonization and subsequent uptake of drug vectors by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) causes nonspecific particle distribution, and ultimately, toxicity. Locally, the vascular endothelium, the combined effect of interstitial and osmotic pressure, disrupted tumor flow, tumor and stroma heterogeneity, extracellular matrix (ECM), cell membrane internalization, endosomal escape, and drug efflux pumps severely reduce drug delivery and toxicity to the tumor. Inversely, these barriers are the same barriers that dictate cancer migration and metastases (Box 1). A rational and systematic approach to understanding these barriers is the key to address cancer complexity, evolution, and spread, through the design of therapeutic strategies capable of selectively and specifically delivering drugs to cancer, even at metastatic sites. Since its conception, the principles outlined within the TOP framework have been applied to develop new and creative therapeutic strategies. For example, an injectable nanoparticle generator has proven successful in treating liver and lung metastases of triple negative breast cancer [4]. This study led to the funding of good manufacturing practice/preclinical studies in preparation for one of the first clinical trials developed around an approach centered on physical principles. Using a similar method, a 70-year-old malaria drug has been recently shown to inhibit the effect of the MPS barrier on drug delivery, yielding a 200% increase in nanoparticle accumulation in tumors, and enhancing organotropic potential of certain delivery vectors [8]. These and other studies have confirmed the critical implications of TOP for nanomedicine, drug vector design, the biodistribution of therapeutics, and therapeutic efficacy. Next, we will outline a few of the open lines of research within the field of TOP, concluding with the proposal for a new tumor classification system based on TOP: transport phenotyping.

Figure 1. Transport Oncophysics Barriers to Drug Delivery and Metastasis.

This figure presents the effect of sequential transport barriers on drug concentration in tumors, and their relationship with cancer hallmarks such as drug resistance, angiogenesis, migration and metastasis, and proliferative signaling (yellow boxes). Transport barriers include the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), tumor vasculature, tumor endothelium, tumor extracellular matrix (ECM), and barriers within cancer cells. (A) When drugs enter the systemic circulation, they first encounter the MPS barrier, constituted by phagocytic cells such as macrophages. Because of sequestration by the MPS, drug concentration in circulation is significantly reduced. (B) Once drugs enter the characteristically disorganized tumor vasculature, created through accelerated tumor angiogenesis, diffusion and convection processes constitute an important local tumor transport barrier. (C) When drugs cross the tumor endothelium barrier, they then need to overcome the ECM barrier to reach cancer cells within the tumor microenvironment. There biophysical markers such as collagen Type IV and drug partitioning may severely affect drug micropharmacokinetics and distribution. In the tumor microenvironment, transport barriers not only affect drug distribution and delivery, but also transport of signaling molecules, whose propagation is affected by obstacles and different material properties. Overall, transport barriers severely hinder the capability of drugs to reach tumors in therapeutically significant concentrations, which contributes to drug resistance. From the tumor microenvironment toward systemic circulation, the same transport barriers modulate cancer cell migration and invasion (Box 1). The description of cancer hallmarks through transport barriers may lead to a new functional and mechanistic understanding of cancer development and treatment.

Box 1. The TOP Framework Applied to Cancer Invasion and Metastasis.

The TOP framework also proposes a new approach to study cancer invasion and metastasis see (Figure 1 in main text). Similar to how transport barriers affect drug delivery to cancer tissue, they also modulate metastatic spread. From the origin site, cancer cell growth is directed through transport barriers such as the MPS, the ECM, and interstitial pressure. To be able to invade, cancer cells need to negotiate the endothelium barrier successfully to enter systemic circulation and spread to distant organs. Some of the unanswered questions in the study of cancer may be tackled with the TOP perspective. For example, it has been hypothesized that under certain clinical conditions, surgical resection of the primary cancer may promote metastatic spread initiation. In the TOP framework, surgical resection may be viewed as an action that results in mitigated local transport barriers, increasing physical access of cancer cells to the systemic blood circulation. Another example can be found in studying the mechanism underlying liver metastasis, one of the most common forms of cancer invasion. The liver constitutes one of the major biological barriers to drug delivery due to both the unique capillary structure and the high concentration of resident macrophages. Cancer cell metastasis to the liver may be approached in the TOP framework by looking at transport mechanisms similar to those that result in particle sequestration by the liver. Finally, the TOP approach supports the argument that drug resistance may be strongly affected by transport properties such as drug partitioning (preferential drug affinity to certain tissue compartments over others) rather than originating purely from biological aspects of resistance.

Diffusion and Convection at the Tumor Endothelium Hinder Drug Penetration

Capitalizing on the interplay between diffusive and convective transport has the potential to improve drug delivery to tumors. For example, a study of the human pulmonary vasculature revealed that convective transport is at least five times more efficient than diffusion in the smallest pulmonary capillaries (diameter = 10 μm, length = 130 μm) [9]. The analysis suggested that free flowing lipo-some-like drug vectors or those targeted to the capillary walls are unlikely to be efficient in the delivery of therapeutic payload [9]. Conversely, drug-loaded extravasating vectors were shown to be more efficient in delivering drugs [9]. This comparison of drug vector localization suggests that diffusive and convective transport mechanisms may be barriers in their own right and thus are critical to control the efficiency of drug delivery at the interface between the systemic circulation and capillary bed of tumor tissues.

Collagen Type IV as a Biophysical Marker for Tumor Micropharmacokinetics

Passive diffusion is often the prevailing mechanism of drug permeation through capillary walls into the tumor microenvironment. Recently, capillary wall Type IV collagen was shown to be a biophysical marker of drug delivery efficiency [10]. In vivo and computational studies indicated that some tumor types possess large collagen accumulation in the basement membrane of the tumor-associated capillaries, which results in reduced diffusion of drug vectors and its payload [10]. Interestingly, the two studied tumor models have shown indistinguishable systemic pharmacokinetics, revealing the important role of pharmacokinetics in the tumor microenvironment – tumor-associated micropharmacokinetics – in determining drug accumulation and response.

Drug Partitioning as Transport Barrier to ECM Penetration and Cellular Uptake

A study of drug partitioning and its role as a cellular or intracellular barrier has confirmed how transport properties can impact drug delivery and, eventually, efficacy. All small molecules can be characterized by their hydrophobicity, frequently expressed as log(P), where P is the partitioning coefficient of the specific molecule. Likewise, therapeutics, once administered, are subject to analogous phenomena when one tissue compartment offers higher affinity to drugs than other compartments. This partitioning phenomenon may lead to drug accumulation in preferred tissue compartments even against drug concentration gradients, which can become critical for drug extravasation and distribution in the tumor microenvironment. For example, the strong preferential accumulation of doxorubicin into the nuclei limits its penetration into tissues to 40–60 mm at most from the vessel walls [11,12], thereby severely hindering drug diffusion deeper into extra-vascular spaces [11].

Concluding Remarks: Transport Phenotyping to Guide Cancer Therapy

Studies as those outlined above confirm the importance of tissue transport properties in controlling the delivery of therapeutics to cancer. Notably, such transport barriers are molecule dependent: defined not only by systemic and tumor microenvironment properties, but also by the therapeutic molecule itself. In the TOP framework, these transport properties can be used to complement current approaches in tumor phenotyping. We have termed this classification of a tumor as its ‘transport phenotype’, which inherits the predictive features of the fundamental laws of physics that govern transport. Determining the transport phenotype of tumors unlocks the possibility of a new understanding of cancer development and treatment. Notably, a TOP-based approach to cancer research grants a new role to informatics; with its unmatched capability to analyze large data sets, computational approaches and artificial intelligence may reveal hidden connections between physical and biological domains of cancer, leading to the development of more efficient drug delivery strategies. Ultimately, we believe that the systematic integration of multidisciplinary approaches at scales from the microenvironment to systemic levels into the TOP-based phenotyping can deepen our mechanistic understanding of cancer biology and lead to the development of efficient and creative therapeutic strategies to revolutionize cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute Physical Sciences-Oncology Network of the National Institutes of Health, under award number U54CA210181. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Breast Cancer Research Program, under award number W81XWH-17–1-0389. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. The authors wish to acknowledge Matthew G. Landry for support with graphics.

Glossary

- Drug partitioning

property of molecules or particles to preferentially accumulate in one tissue compartment over another. Drug partitioning is expressed as the ratio of concentrations between different compartments (i.e., capillary wall vs. plasma, cancer cell nucleus vs. cytoplasm).

- Transport barriers

tissues, organs, and their transport properties hindering or modulating mass transport efficiency as it pertains to drug delivery and cancer cell migration. Examples of transport barriers are the MPS, the vascular wall permeability, the ECM, and interstitial pressure.

- Transport oncophysics

discipline that studies cancer through the physical phenomena of mass transport.

- Transport oncophysics framework

underlying theoretical and conceptual approach to treat cancer development, spread, drug delivery, and treatment in terms of mass transport.

- Transport phenotype

tumor or subject phenotyping based on specific transport properties, instead of purely biological or genetic markers.

- Tumor micropharmacokinetics

pharmacokinetics that specifically addresses kinetics and biodistribution of drugs and particles in the capillary bed of tumor microenvironment.

Footnotes

Resources

References

- 1.Ferrari M (2010) Frontiers in cancer nanomedicine: directing mass transport through biological barriers. Trends Biotechnol 28, 181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco E et al. (2015) Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 941–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari M (2005) Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu R et al. (2016) An injectable nanoparticle generator enhances delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol 34, 414–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Letai A (2017) Functional precision cancer medicine-moving beyond pure genomics. Nat. Med 23, 1028–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michor F et al. (2011) What does physics have to do with cancer? Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 657–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D and Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfram J et al. (2017) A chloroquine-induced macrophage-preconditioning strategy for improved nanodelivery. Sci. Rep 7, 13738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziemys A et al. (2016) Computational analysis of drug transport in tumor microenvironment as a critical compartment for nanotherapeutic pharmacokinetics. Drug Deliv 23, 2524–2531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoi K et al. (2014) Capillary-wall collagen as a biophysical marker of nanotherapeutic permeability into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res 74, 4239–4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoi K et al. (2015) Liposomal doxorubicin extravasation controlled by phenotype-specific transport properties of tumor microenvironment and vascular barrier. J. Control Release 217, 293–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tannock I et al. (2002) Limited penetration of anticancer drugs through tumor tissue. Clin. Cancer Res 8, 878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]