Abstract

Background:

Association between high adiposity and the clinical progression of dementia remains puzzling.

Objective:

To separately examine the association between body mass index (BMI) and cognitive, functional, and behavioral declines before, at, and after diagnosis of dementia, and further stratified by age groups, and sex.

Methods:

A total of 1,141 individuals with incident dementia were identified from the Uniform Data Set of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. Cognitive function was evaluated by Mini-Mental State Exam, functional abilities were assessed using Functional Activities Questionnaire, and behavioral symptoms were captured by Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire at each follow-up visit. We used separate linear-mixed effects models to examine the association.

Results:

Compared to moderate baseline BMI, high baseline BMI was associated with 0.30-point slower annual progression rates in functional decline. For individuals aged 76 and over, high baseline BMI was associated with 0.42-point faster progression rates in cognitive decline annually. A U-shaped association between baseline BMI and cognitive decline was observed among men.

Conclusion:

BMI levels before dementia diagnosis may facilitate the identification of different risk profiles for progression rates of cognitive and functional declines in individuals who developed dementia.

Keywords: Dementia, Body Mass Index, Cognition, Behavior, Disease Progression, Neuropsychological Tests, Public Health

Introduction

Dementia affects more than 5 million Americans age 65 and older and this number is expected to triple by 2050 [1]. Growing evidence suggests that cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. overweight or obesity, high cholesterol, hypertension, and diabetes) are important risk factors for dementia [2, 3]. However, the mechanism behind the association of high adiposity with the risk of dementia remains unclear. While some studies showed that higher weight or body mass index (BMI) at age 50 years is associated with increased risk of dementia [4–8], others observed an inverse association in individuals at age 65 years and older [9–12], which constitutes the so-called “obesity paradox” in the literature [13, 14]. Moreover, some studies have reported a U-shaped relation (underweight and overweight or obese individuals are more likely to develop dementia than individuals with normal weight) between BMI and dementia at older ages [15, 16].

The clinical progression of dementia includes progressive decline in cognitive and functional abilities, and a variety of behavioral symptoms that occur throughout the disease spectrum. Since cognitive impairment is the defining characterization of dementia, studies investigating the association between BMI and the progression of dementia commonly focused on the cognition domain of the disease, which has prompted the development of different scales, such as global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), in longitudinal studies or clinical trials of potential treatments [17]. Nevertheless, functional limitations and behavioral problems are also critical parts of the disease characteristics. Using CDR Sum of Boxes Scale (CDR-SB), Besser et al. [18] investigated the association between BMI or one-year weight change, and cognitive and functional impairments simultaneously; however, their study did not examine the association between BMI and changes in cognitive, functional, and behavioral declines over time separately. Moreover, whether BMI at different disease stages (before, at, and after dementia diagnosis) are prospectively associated with the clinical progression of dementia, defined by the aforementioned three domains, has not been extensively investigated. Studies have shown that BMI declined over time up to clinical onset of dementia but no significant decrease was found afterward [4].

Accordingly, our study seeks to examine: 1) whether BMI at study baseline or at diagnosis of dementia are prospectively associated with the clinical progression of dementia, defined by cognition, function, and behavior and 2) whether the associations were modified by age groups or other demographic characteristics, such as sex. This study fills an important gap in the literature by longitudinally evaluating the role of BMI on dementia progression.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Subjects

We obtained panel data, collected between September 2005 and December 2016, from the Uniform Data Set (UDS) of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC). The UDS includes subjects with a range of cognitive characteristics, i.e. normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and demented, and their demographic and clinical data from 39 (29 in our analysis sample) past and present Alzheimer Disease Centers (ADCs), which enroll and follow subjects with their own protocols. The UDS was collected annually via a standardized evaluation of subjects either during the office visit, home visit, or over the phone by a trained clinician or clinic personnel during the annual assessment. The information was either provided from the subjects themselves or their informants, or assessed by clinicians. Diagnosis was made by either a consensus team or a single physician (the one who conducted the examination); this process varies according to each ADC’s protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and informants. Research using the NACC database was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington. Because the recruitment objectives and referral methods vary greatly by each ADC, the UDS is not a representative sample and thus would not be appropriate to be applied to estimates for the general US population [19].

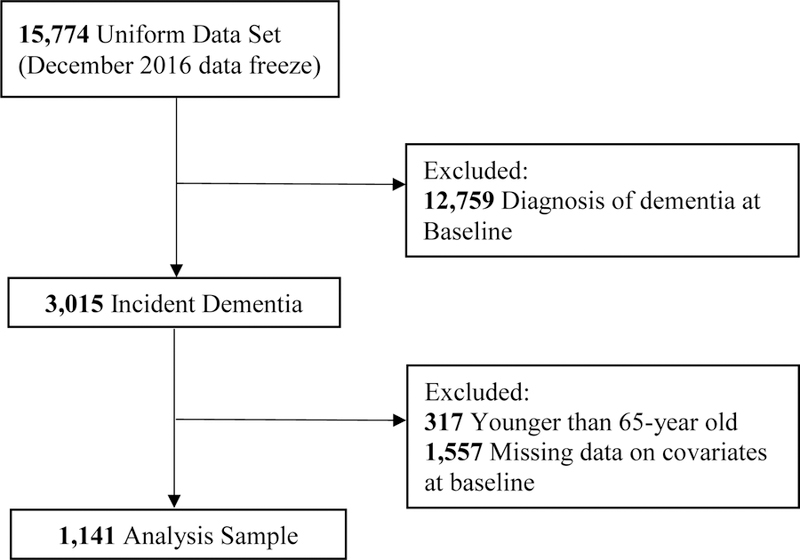

Our analysis sample was confined to subjects with newly diagnosed dementia (incident dementia), due to an extensive variation of conversion rates from MCI to dementia [20–22], at any follow-up visit and aged 65 and older. We only included individuals with complete observations on variables of interest at their baseline visit, which yielded a study sample of 1,141 subjects (Figure 1) where 86% had an etiologic diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The average length of follow-up was 5.1 years (range of 0.5–11.0 years). Furthermore, to evaluate the potential selection bias from excluding subjects without complete observation on variables of interest from the analysis sample, we compared the baseline characteristics between included subjects and excluded subjects. Results showed that excluded subjects (n= 1,557) had lower baseline MMSE scores, and higher baseline scores of Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) and Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q), compared to included subjects. No significant difference was found between these two groups in terms of age and BMI at baseline (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study sample selection flowchart.

Measures of Clinical Progression

Clinical progression of dementia was evaluated by a global measure of each domain (cognition, function, and behavior), at each follow-up. Based on most commonly used measurements, cognitive function was evaluated by MMSE with scores ranged 0–30 [23]; functional abilities were assessed using FAQ with scores ranged 0–30 [24]; and behavioral symptoms were captured by NPI-Q with scores ranged 0–36 [25]. Except for MMSE, the greater scores represent a greater impairment for all the measurements.

Predictor

BMI (kg/m2) was the main variable of interest and was calculated 1) at the baseline visit (baseline BMI), and 2) at the visit where the diagnosis of dementia was made (index BMI). Both baseline and index BMI were then categorized as low (<20.0), moderate (≥20.0 and <27.5), or high (≥27.5) based on the suggestion that higher cutoff points may be more appropriate for the older adults due to its significant association with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality for individuals in the elder group [18, 26].

Covariates

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, education level, marital status, race, living arrangement, and place of residence. The education level was measured as the number of years of schooling. Marital status was categorized into three groups (married, widowed, and others) as well as race (white, African American, and others), and living arrangement (living alone, living with spouse, and living with others). Place of residence was grouped into community or nursing facility. In addition, variables of apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 genotype (yes/no) and the first-degree family member with dementia (yes/no) were also included. Clinical risk factors included subjects’ self-reported history of congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. All covariates were coded as time-invariant and were collected at each follow-up visit. We defined the age at diagnosis of dementia as the age when the first dementia incidence occurred.

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical covariates were compared among BMI categories using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 test or the Fisher exact test (given the potential small number in certain cells) for categorical variables. We further performed post-hoc test if the results were significant. Dunnett’s test was used to adjust p-values for the multiple comparisons in terms of covariates for low vs. moderate BMI, and high vs. moderate BMI (moderate BMI was the reference group). We next used separate linear mixed-effects models to examine: 1) whether there were significant differences in the clinical progression evaluated by cognitive function, functional abilities, and behavioral symptoms, by baseline BMI and index BMI groups; and 2) whether the associations were modified by age or sex. Random patient and ADC effects were included to account for correlations among repeated measures of the same patients and recruitment centers. To account for the progression of clinical outcomes, time was included as random effects terms for both intercepts and slopes. MMSE, FAQ, and NPI-Q scores were coded as time-variant (by each visits) allowing for the estimate of average changes over time. We assumed the exchangeable correlation structure for the random effects.

Baseline BMI model

The core models included a term for time, baseline BMI, and the interaction term for time and baseline BMI. Time was defined as “number of years since the baseline visit” because: 1) the clinical progression may occur before dementia diagnosis [27, 28]; and 2) it is challenging to timely capture the dementia conversion (the follow-up visit repeated on an annual basis); and was adjusted for the different follow-up duration between BMI groups. The coefficients for the interaction terms (baseline BMI × time) were interpreted as a faster rate of FAQ or NPI-Q progression when the values were positive, and as a slower progression when the values were negative. For MMSE measurement, positive values indicated slower progression rates, and negative values represented faster progression rates. The coefficients of BMI alone were interpreted as the difference of mean baseline scores in terms of MMSE, FAQ and NPI-Q between baseline BMI categories.

In the multivariable models, we included sociodemographic and clinical factors measured at baseline in addition to BMI for adjusted estimates. In the models respectively evaluating functional and behavioral declines, the cognition measurement (MMSE) was also included as a time-varying main effect because it is commonly used for the diagnosis of dementia and the indicator of disease severity. We further tested the three-way interaction between BMI categories, time, and age at baseline (65–75 year-old, or >75 year-old) or sex.

Index BMI model

We used similar models (the core and multivariable models) to examine the associations between index BMI and the clinical progressions of dementia. Here, however, time was defined as “number of years since the diagnosis of dementia” as opposed to “number of years since the baseline visit” in the baseline BMI model. Sociodemographic and clinical factors measured at time of dementia diagnosis were included for adjusted estimates. To examine the association between index BMI and clinical progression rates of dementia, we further limited our analyses to observations occurred at and after the diagnosis of dementia (n=984). The average follow-up time from dementia diagnosis was 1.9 (standard deviation [SD], 2.0) years.

Sensitivity analysis

To compare with the existing literature using standard BMI cut-off values [29], we conducted additional analyses of baseline BMI and index BMI models by defining BMI levels as: low (<24.9), moderate (25.0–29.9), and high (>29.9). In an effort to assess the robustness of our findings based on alternative specifications of BMI, we replicated the analyses by 1) treating baseline and index BMI as continuous variables, and 2) using changes in BMI, defined as the difference in BMI between baseline and dementia diagnosis, in all the models and assessed whether and the extent to which our findings would still hold.

Moreover, to know whether the study results could be replicated in the face of alternative measurements, we conducted analyses using global CDR, and geriatric depression scale (GDS), and other neuropsychological tests (i.e., the logical memory test, digit span forward and backward tests, category fluency test, Trail Making TEST [TMT] - Part A & B, WAIS-R digit symbol test, and Boston Naming test) as outcome variables and assessed the robustness of our results.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 describes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample at baseline (characteristics at diagnosis of dementia were presented in the Supplementary Table 2). Of the 1,141 subjects who met the study inclusion criteria, the mean age at baseline was 77.7 (SD, 7.0) years with an average baseline BMI of 26.1 (SD, 4.3), and 47% carried the APOE ϵ4 genotype. In terms of other demographic compositions, 43% was male, 62% was married and living with spouse, 10% was African American, and 1 % was living at a facility. At the time of dementia diagnosis, the mean scores of MMSE, FAQ, and NPI-Q were 24.1 (SD, 3.7), 12.1 (SD, 7.6), and 3.7 (SD, 3.9), respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample at baseline, by baseline BMI category.

| baseline BMIf (n=1,141) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variablea | Low (n=53) | Moderate (n=697) | High (n=391) | P-value | All |

| Age, mean (SD) | 80.1 (7.8) | 78.1 (6.9) | 76.6*** (6.7) | <0.001 | 77.7 (7.0) |

| Male, N (%) | 7*** (13) | 306 (44) | 181 (46) | <0.001 | 494 (43) |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 15.4 (3.3) | 15.5 (3.0) | 15.1 (3.1) | 0.157 | 15.4 (3.1) |

| Marital status | 0.003 | ||||

| Married, N (%) | 23 (43) | 455 (65) | 230 (59) | 708 (62) | |

| Windowed/Divorced/Separated, N (%) | 23 (43) | 209 (30) | 140 (36) | 372 (33) | |

| Other,b N (%) | 7 (13) | 33 (5) | 21 (5) | 61 (5) | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||

| White, N (%) | 50 (94) | 631 (91) | 320 (82) | 1,001 (88) | |

| African American, N (%) | 1 (2) | 49 (7) | 58 (15) | 108 (10) | |

| Other,c N (%) | 2 (4) | 17 (2) | 13 (3) | 32 (3) | |

| Living arrangement, % | 0.003 | ||||

| Living alone, N (%) | 23 (43) | 191 (27) | 117 (30) | 331 (29) | |

| Living with spouse, N (%) | 23 (43) | 455 (65) | 228 (58) | 706 (62) | |

| Living with others,d N (%) | 7 (13) | 51 (7) | 46 (12) | 104 (9) | |

| Residence | 0.134 | ||||

| Community, N (%) | 51 (96) | 691 (99) | 387 (99) | 1,129 (99) | |

| Facility,e N (%) | 2 (4) | 6 (1) | 4 (1) | 12 (1) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Congestive heart failure, N (%) | 0 | 14 (2) | 13 (3) | 0.199 | 27 (2) |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 2 (4) | 63 (9) | 73*** (19) | <0.001 | 138 (12) |

| Stroke, N (%) | 3 (6) | 34 (5) | 29 (7) | 0.227 | 66 (6) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 23 (43) | 341 (49) | 274*** (70) | <0.001 | 638 (56) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, N (%) | 16** (30) | 352 (51) | 237** (61) | <0.001 | 605 (53) |

| APOE genotype, N % | 0.673 | ||||

| No ϵ4 allele | 27 (51) | 365 (52) | 215 (55) | 607 (53) | |

| had ϵ4 allele | 26 (49) | 332 (48) | 176 (45) | 534 (47) | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 18.9*** (1.0) | 24.1 (2.0) | 30.8*** (3.3) | <0.001 | 26.1 (4.3) |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 26.9 (3.3) | 27.2 (2.4) | 27.2 (2.3) | 0.926 | 27.2 (2.4) |

| FAQ, mean (SD) | 3.5 (5.5) | 3.6 (5.0) | 3.9 (5.2) | 0.159 | 3.7 (5.1) |

| NPI-Q, mean (SD) | 1.7 (2.6) | 2.0 (3.0) | 2.6 (3.4) | 0.057 | 2.2 (3.1) |

| Global CDR, mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 0.136 | 1.7 (0.5) |

| CDR-SB, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.3) | 0.229 | 1.2 (1.3) |

| GDS, mean (SD) | 2.1 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.1) | 2.1 (2.4) | 0.421 | 2.3 (2.3) |

| 1st degree family with dementia, N (%) | 32 (60) | 455 (65) | 255 (65) | 0.767 | 742 (65) |

| Year of follow-up since baseline, mean (SD) | 5.2 (2.6) | 5.2 (2.6) | 5.1 (2.6) | 0.971 | 5.2 (2.6) |

Note. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; FAQ, Functional Activities; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; CDR, clinical dementia rating; CDR-SB, clinical dementia rating sum of boxes; GDS, geriatric depression scale; SD, standard deviation.

Characteristics were compared using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous covariates and χ2 test or the Fisher exact test (given the potential small number in certain cells) for categorical covariates. Pairwise comparisons (relative to moderate BMI; α level=0.05/2=0.025) would be conducted with adjusted p-value, if Kruskal-Wallis test or χ2 test (or the Fisher exact test) showed significant results.

Other included never married, living as married/ domestic partner, and unknown.

Other included American Indians, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians, Asians, and individuals who identified themselves as multiracial.

Living with Others included living with relatives, or caregivers, and living with a group.

Facility included assisted living and nursing home.

Low BMI is <20 kg/m2, moderate BMI is 20 to <27.5 kg/m2, and high BMI is ≥27.5 kg/m2.

p < 0.005 and

p < 0.0005 indicated the results of pairwise comparisons.

Effect of Baseline BMI on Cognition, Function, and Behavior

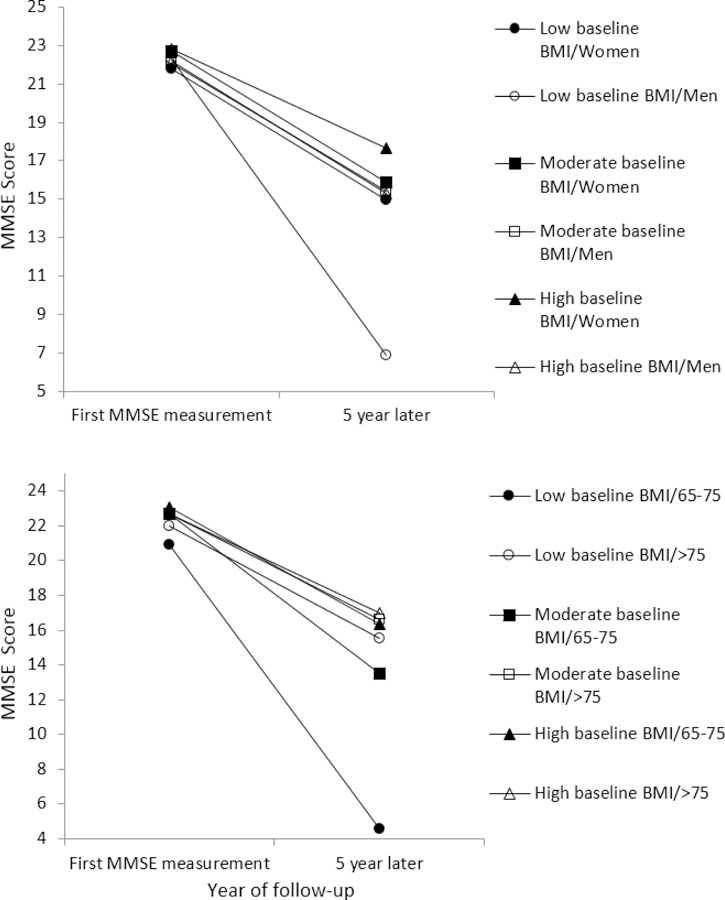

Adjusted baseline BMI model, Cognition

Relative to moderate baseline BMI, low baseline BMI was associated with an average 0.81-point lower (95% confidence interval [CI]: −1.40, −0.22) baseline MMSE scores but no significant difference was found for the clinical progression rate; no association was found between high baseline BMI and baseline MMSE scores or annual clinical progression rate (Table 2). Stratified by sex, however, Figure 2A showed that among men with incident dementia a faster progression rate was found for low baseline BMI (p =0.003) and high baseline BMI (p = 0.046) compared to moderate baseline BMI. Results based on stratified analysis by age groups suggested that compared to subjects aged between 65–75, low baseline BMI was associated with a slower progression rate (p =0.020), whereas high baseline BMI was associated with a faster progression rate (p =0.045), among those who aged 76 and older (Figure 2B).

Table 2.

Multivariable model results of differences in clinical progression by baseline BMI levels.

| Cognition (MMSE) | Function (FAQ) | Behavior (NPI-Q) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Mean scores at baseline (ref = moderate baseline BMI) | ||||||||

| Low baseline BMI | −0.63* (−1.22, −0.04) | −0.81** (−1.40, −0.22) | −0.02 (−1.25, 1.20) | −0.52 (−1.62, 0.58) | −0.30 (−0.88, 0.28) | −0.13 (−0.71, 0.45) | ||

| High baseline BMI | −0.14 (−0.40, 0.12) | 0.02 (−0.25, 0.28) | 0.65*(0.10, 1.20) | 0.41 (−0.10, 0.91) | 0.49*** (0.23, 0.75) | 0.33** (0.07, 0.60) | ||

| Annual progression rate (ref = moderate baseline BMI) | ||||||||

| Low baseline BMI | −0.25 (−0.67, 0.17) | −0.23 (−0.64, 018) | 0.64 (−0.20, 1.47) | 0.33 (−0.31, 0.97) | 0.08 (−0.17, 0.33) | 0.03 (−0.25, 0.30) | ||

| High baseline BMI | 0.15 (−0.03, 0.34) | 0.16 (−0.02, 0.34) | −0.56** (−0.93, −0.18) | −0.30* (−0.58, −0.01) | −0.02 (−0.14, 0.09) | 0.01 (−0.11, 0.14) | ||

Note. BMI, body mass index; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; FAQ, Functional Activities Questionnaire; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.

Parenthesis indicates 95% confidence interval.

Positive values indicated a slower progression rate, and negative values represented a faster progression rate. Covariates included age at baseline, sex, education level, marital status at baseline, race, living arrangement at baseline, residence at baseline, clinical history at baseline (congestive heart failure, diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia), family history of dementia, and APOE ϵ4 status.

Positive values were interpreted as a faster progression rate, and negative values indicated a slower progression rate. Covariates included MMSE, age at baseline, sex, education level, marital status at baseline, race, living arrangement at baseline, residence at baseline, clinical history at baseline (congestive heart failure, diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia), family history of dementia, and APOE ϵ4 status.

Low BMI is <20 kg/m2, moderate BMI is 20 to <27.5 kg/m2, and high BMI is ≥27.5 kg/m2.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Clinical progression in cognition (MMSE, range: 0–30) by baseline BMI and sex or age groups at baseline. Higher MMSE scores indicate greater cognitive function. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; BMI, body mass index.

Adjusted baseline BMI model, Function

High baseline BMI was associated with 0.30-point (95% CI: −0.58, −0.01) slower annual progression rates compared to moderate baseline BMI, whereas low baseline BMI was not significantly associated with annual progression rates, compared to moderate baseline BMI (Table 2). We did not find significant difference in baseline FAQ scores between baseline BMI categories. No significant difference in FAQ progression rates by baseline BMI categories was found when stratified by age groups or sex (data not shown).

Adjusted baseline BMI model, Behavior

Relative to moderate baseline BMI, high baseline BMI was associated with an average 0.33-point higher (95% CI: 0.07, 0.60) baseline NPI-Q scores. No significant differences in annual clinical progression rates were observed across baseline BMI categories for behavioral symptoms (Table 2). In addition, we did not find any difference on NPI-Q decline rate by baseline age groups or sex.

Effect of Index BMI on Cognition, Function, and Behavior

Adjusted index BMI model, Cognition

Low index BMI was associated with an average 2.16-point lower (95% CI: −3.59, −0.74) MMSE scores at dementia diagnosis, whereas high index BMI was associated with 0.25-point (95% CI: 0.01, 0.49) slower progression rates in cognitive decline, compared to moderate index BMI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable model results of differences in clinical progression by index BMI levels.

| Cognition (MMSE) | Function (FAQ) | Behavior (NPI-Q) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Mean scores at diagnosis (ref = moderate index BMI) | ||||||||

| Low index BMI | −1.72* (−3.33, −0.10) | −2.16** (−3.59, −0.74) | 1.36 (−1.09, 3.81) | 0.05 (−2.41, 2.50) | −0.46 (−1.70, 0.78) | −0.18 (−1.51, 1.15) | ||

| High index BMI | −0.45 (−1.31, 0.42) | −0.28 (−1.03, 0.47) | 0.36 (−0.96, 1.68) | −0.15 (−1.53, 1.23) | 0.89** (0.24, 1.55) | 0.64 (−0.08, 1.35) | ||

| Annual progression rate (ref = moderate index BMI) | ||||||||

| Low index BMI | 0.24 (−0.23, 0.70) | 0.28 (−0.15, 0.71) | −0.02 (−0.71, 0.66) | 0.12 (−0.52, 0.77) | 0.01 (−0.29, 0.32) | −0.02 (−0.37, 0.32) | ||

| High index BMI | 0.25 (−0.01, 0.52) | 0.25* (0.01, 0.49) | −0.23 (−0.62, 0.17) | 0.03 (−0.35, 0.41) | −0.12 (−0.29, 0.05) | −0.11 (−0.30, 0.08) | ||

Note. BMI, body mass index; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; FAQ, Functional Activities Questionnaire; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.

Index BMI indicates the BMI measured at the visit in which dementia diagnosis was made.

Parenthesis indicates 95% confidence interval.

Positive values indicated a slower progression rate, and negative values represented a faster progression rate. Covariates included age at diagnosis, sex, education level, marital status at diagnosis, race, living arrangement at diagnosis, residence at diagnosis, clinical history at diagnosis (congestive heart failure, diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia), family history of dementia, and APOE ϵ4 status.

Positive values were interpreted as a faster progression rate, and negative values indicated a slower progression rate. Covariates included MMSE, age at diagnosis, sex, education level, marital status at diagnosis, race, living arrangement at diagnosis, residence at diagnosis, clinical history at diagnosis (congestive heart failure, diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia), family history of dementia, and APOE ϵ4 status.

Low BMI is <20 kg/m2, moderate BMI is 20 to <27.5 kg/m2, and high BMI is ≥27.5 kg/m2.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Adjusted index BMI model, Function

The results revealed no significant difference in FAQ scores at the time of diagnosis or annual progression rates by index BMI categories (Table 3).

Adjusted index BMI model, Behavior

There was no significant association between index BMI categories and mean NPI-Q scores at diagnosis of dementia or annual progression rates of NPI-Q (Table 3).

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of our findings based on alternative specifications of BMI, multivariable results using standard BMI cut-off values reported similar results as analyses used cut-off values defined in the present study (Supplementary Table 3 and Table 4). One major difference was that high baseline BMI no longer had any significant association with functional decline compared to moderate baseline BMI when standard BMI cut-off values were used.

In the post-hoc analysis, results of multivariable models with BMI coded as a continuous and time-variant variable indicated that higher BMI was associated with slower progression of dementia than lower BMI, which was similar to the results from the original models treating BMI as a categorical variables (data not shown). We did not find any association when using changes in BMI between baseline and dementia diagnosis as an outcome variable (data not shown).

High baseline BMI (−0.04; 95% CI: −0.06, −0.02) and high index BMI (−0.03; 95% CI: −0.06, - 0.001) were both associated with slower CDR decline rates, compared to moderate baseline or index BMI (Supplementary Table 5). We found no significant association between baseline or index BMI categories and annual progression rates of GDS (Supplementary Table 6). Using other neuropsychological tests as an outcome variable in the multivariable models, results showed that high baseline BMI was associated with 1.80-point slower progression rates in executive function with the TMT- Part A (95% CI: −3.07, −0.54) (Supplementary Table 7); whereas high index BMI was associated with 0.93-point slower progression rates in processing speed and executive function with the WAIS-R digit symbol test (95% CI: 0.20, 1.65) (Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

Our results showed some associations between BMI levels and dementia progression based on different measurements. High baseline BMI and high index BMI were both associated with slower progression of functional or cognitive declines, respectively, which were comparable to the results of Besser et al. [18] using a similar dataset but different measurements (CDR-SB, the combination of cognition and function assessment). To assess the replicability, we further used not only CDR-SB but also other neuropsychological tests as an outcome variable and conducted the analyses with our analysis sample and models. Our results indicated that high BMI was significantly associated with slower progression rates of CDR-SB (Supplementary Table 9), TMT- Part A and WAIS-R digit symbol; whereas this association was not found significant in their study but with a similar direction. This may have been resulted from different inclusion criteria of the analysis sample (incident dementia in our case vs. AD) and covariates included in the multivariable models between the two studies.

Different from Besser et al.’s study looking at the BMI level at diagnosis of AD and percent changes in weight between weights at the time of AD diagnosis and one-year later, we examined the level of BMI both before and at diagnosis of dementia, and found that dementia progression in the domains of cognition and function was consistently slower among individuals with high BMI compared to those with moderate BMI after controlling for cardiovascular risk factors (CHF, diabetes, stroke, and hypertension). Our results reinforce corresponding findings from previous studies documenting that high BMI at older age may have protective effects against the progression of dementia [18, 30, 31]. This might be due to the “survival bias effect” [32], in which subjects with high BMI who survived to older age might be healthier among their peers due to a proper management of their cardiovascular disease risk factors [33].

Extant evidence on the association between BMI, and dementia risk or cognitive decline, is not consistent [5, 15, 16, 34, 35]. Two recent studies using the NACC Neuropathology Data Set both found that lower later-life BMI projected greater odds of AD neuropathology among subjects with normal cognition [36] and MCI [33]. In our case, low baseline BMI was associated with significantly lower cognition test scores (MMSE) at baseline and index time points. However, low baseline BMI was not associated with a faster progression in cognitive, functional, or behavioral declines. Further analyses stratified by age groups suggested that low baseline BMI was related to worse cognitive function in the younger elders (65–75 year-old), but not the older population (> 75 year-old). Low baseline BMI might be indicative of poor health and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes) at older ages [6, 15], and/or a loss of appetite or taste due to the pathophysiological alterations [4, 11, 37]. As a result, BMI in later life may constitute different risk profiles in individuals who convert to dementia [18, 33, 36, 38].

Although we did not find a U-shaped relationship between baseline BMI and cognitive decline by age groups in the whole sample, this relationship might be modified by sex. In our case, low and high baseline BMI were associated with a faster progression rate in cognitive decline compared to moderate baseline BMI among men, as suggested in the literature [39, 40]. It was postulated that sex differences in dementia risks are likely to be mediated via actions of sex steroid hormones, as well as by differences in neurophysiological substrates, physiological development, and environmental and modifiable lifestyle factors between men and women [31, 41]. For example, studies have shown that, in women, reductions in lifetime exposure to estrogens are associated with increased AD risks [42], whereas a large randomized clinical trial found that hormone therapy was associated with an increased risk of AD in postmenopausal women aged 65 years and older [43, 44]. Factors underlying the association in terms of sex have been extensively but incompletely described in the literature [41]. Future studies should further address the role of sex in these associations rather than a simple controlling for sex.

The biologic underpinnings of the obesity paradox as it relates rate of cognitive and functional declines in individuals who develop dementia remain underexplored. It is possible that persons with low BMI may have nutritional deficiencies that enhance neurodegeneration, such as low vitamin B levels with secondary elevation of homocysteine levels [45], or have low levels of important brain trophic factors (e.g. brain-derived neurotrophic factor -BDNF) that enhance neurodegeneration [46]. Similarly, the exact reason for which dementia patients with high BMI have a slower rate of cognitive and functional declines is not known. A focus on the impact of differences in levels of brain trophic factors and hormonal differences based upon BMI that might be neuroprotective may lead to answers.

Several limitations need to be noted. Although previous studies have shown that the weight loss might be a risk factor for dementia [15], we did not examine the weight change one-year before the onset of dementia as what has been done in the previous study [18] because: 1) weight loss may precede at least a decade before dementia diagnosis [34, 47]; and 2) there are some misdiagnosis issues embedded in dementia studies [48]. Thus it may not correctly identify the temporal relationship between weight changes and clinical progression of dementia [49]. Together, these limitations may inflate the effect of using one-year weight change as one of the measurements. However, in the post-hoc sensitivity analysis, we did not find an association when using changes in BMI (weight) between baseline and dementia diagnosis as an outcome variable. Second, BMI may not be an appropriate metric of adiposity for older adults due to age-related loss of lean body mass such as sarcopenia [33]. Analyses using other measurements (e.g. waist circumference, or waist-to-hip ratio) would shed some light on studies examining the relationship between adiposity and the risk of dementia. Lastly, we recognized the limitation of the very small sample size in the low BMI subgroup, resulting from the BMI cutoff values used in the present study. However, our study findings remain hold with similar results using standard cutoff values in the sensitivity analyses.

In conclusion, our study confirmed the recent evidence regarding the inverse association between BMI and the clinical progression of dementia by using more comprehensive measures in newly diagnosed dementia patients compared to those used in the previous studies. Furthermore, a U-shaped association between baseline BMI and cognitive decline was observed among men. Our results may facilitate the identification of unique risk profiles for rates of progressive decline in cognition and function for dementia patients, based upon BMI, age, and sex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the NACC. The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD) , P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Funding sources: None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Reference

- [1].Alzheimer’s Association (2016) 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 12, 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K (2005) Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology 64, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kloppenborg RP, van den Berg E, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ (2008) Diabetes and other vascular risk factors for dementia: which factor matters most? A systematic review. Eur J Pharmacol 585, 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gu Y, Scarmeas N, Cosentino S, Brandt J, Albert M, Blacker D, Dubois B, Stern Y (2014) Change in body mass index before and after Alzheimer’s disease onset. Curr Alzheimer Res 11, 349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Xu W, Atti A, Gatz M, Pedersen N, Johansson B, Fratiglioni L (2011) Midlife overweight and obesity increase late-life dementia risk A population-based twin study. Neurology 76, 1568–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Diehr P, O’Meara ES, Longstreth W, Luchsinger JA (2009) Midlife and late-life obesity and the risk of dementia: cardiovascular health study. Arch Neurol 66, 336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gustafson DR, Bäckman K, Joas E, Waern M, Östling S, Guo X, Skoog I (2012) 37 years of body mass index and dementia: observations from the prospective population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. J Alzheimers Dis 28, 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Kåreholt I, Winblad B, Helkala E-L, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Nissinen A (2005) Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 62, 1556–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Power BD, Alfonso H, Flicker L, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Almeida OP (2013) Changes in body mass in later life and incident dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 25, 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hughes T, Borenstein A, Schofield E, Wu Y, Larson EB (2009) Association between late-life body mass index and dementia The Kame Project. Neurology 72, 1741–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Atti AR, Palmer K, Volpato S, Winblad B, De Ronchi D, Fratiglioni L (2008) Late‐life body mass index and dementia incidence: nine‐year follow‐up data from the Kungsholmen Project. J Am Geriatr Soc 56, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tolppanen A-M, Ngandu T, Kåreholt I, Laatikainen T, Rusanen M, Soininen H, Kivipelto M (2014) Midlife and late-life body mass index and late-life dementia: results from a prospective population-based cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 38, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Freedman D, Ron E, Ballard-Barbash R, Doody M, Linet M (2006) Body mass index and all-cause mortality in a nationwide US cohort. Int J Obes 30, 822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Curtis JP, Selter JG, Wang Y, Rathore SS, Jovin IS, Jadbabaie F, Kosiborod M, Portnay EL, Sokol SI, Bader F (2005) The obesity paradox: body mass index and outcomes in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 165, 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Luchsinger JA, Patel B, Tang M-X, Schupf N, Mayeux R (2007) Measures of adiposity and dementia risk in elderly persons. Arch Neurol 64, 392–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Beydoun MA, Beydoun H, Wang Y (2008) Obesity and central obesity as risk factors for incident dementia and its subtypes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obes Rev 9, 204–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mohs RC, Schmeidler J, Aryan M (2000) Longitudinal studies of cognitive, functional and behavioural change in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Stat Med 19, 1401–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Besser LM, Gill DP, Monsell SE, Brenowitz W, Meranus D, Kukull W, Gustafson DR (2014) Body mass index, weight change, and clinical progression in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 28, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, The UDS study population, https://www.alz.washington.edu/WEB/study_pop.html, Accessed Feburary 8.

- [20].Mitchell AJ, Shiri‐Feshki M (2009) Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia–meta‐analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 119, 252–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ward A, Tardiff S, Dye C, Arrighi HM (2013) Rate of conversion from prodromal Alzheimer’s disease to Alzheimer’s dementia: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra 3, 320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Michaud TL, Su D, Siahpush M, Murman DL (2017) The risk of incident mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia considering mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra 7, 15–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pfeffer R, Kurosaki T, Harrah C, Chance J, Filos S (1982) Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. Journal of Gerontology 37, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J (1994) The Neuropsychiatric Inventory comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 44, 2308–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Heiat A (2003) Impact of age on definition of standards for ideal weight. Preventive Cardiology 6, 104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Prince M, Bryce R, Ferri C (2011) World Alzheimer Report 2011: The benefits of early diagnosis and intervention, Alzheimer’s Disease International. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dubois B, Padovani A, Scheltens P, Rossi A, Dell’Agnello G (2015) Timely Diagnosis for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Literature Review on Benefits and Challenges. J Alzheimers Dis 49, 617–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, About Adult BMI, https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html, Accessed November 29.

- [30].Dahl AK, Löppönen M, Isoaho R, Berg S, Kivelä SL (2008) Overweight and obesity in old age are not associated with greater dementia risk. J Am Geriatr Soc 56, 2261–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Moser VA, Pike CJ (2016) Obesity and sex interact in the regulation of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 67, 102–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tobias DK, Hu FB (2013) Does being overweight really reduce mortality? Obesity 21, 1746–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alosco ML, Duskin J, Besser LM, Martin B, Chaisson CE, Gunstad J, Kowall NW, McKee AC, Stern RA, Tripodis Y (2017) Modeling the relationships among late-life body mass index, cerebrovascular disease, and Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology in an autopsy sample of 1,421 subjects from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Data Set. J Alzheimers Dis 57, 953–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Stewart R, Masaki K, Xue Q-L, Peila R, Petrovitch H, White LR, Launer LJ (2005) A 32-year prospective study of change in body weight and incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Arch Neurol 62, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Qizilbash N, Gregson J, Johnson ME, Pearce N, Douglas I, Wing K, Evans SJ, Pocock SJ (2015) BMI and risk of dementia in two million people over two decades: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 3, 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Besser LM, Alosco ML, Ramirez Gomez L, Zhou X-H, McKee AC, Stern RA, Gunstad J, Schneider JA, Chui H, Kukull WA (2016) Late-life vascular risk factors and Alzheimer disease neuropathology in individuals with normal cognition. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 75, 955–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Knopman DS, Edland S, Cha R, Petersen RC, Rocca WA (2007) Incident dementia in women is preceded by weight loss by at least a decade. Neurology 69, 739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Bennett DA, Barnes LL (2018) Body Mass Index and Decline in Cognitive Function in Older Black and White Persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 73, 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Elias M, Elias P, Sullivan L, Wolf P, D’agostino R (2003) Lower cognitive function in the presence of obesity and hypertension: the Framingham heart study. International Int J Obes 27, 260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kanaya AM, Lindquist K, Harris TB, Launer L, Rosano C, Satterfield S, Yaffe K (2009) Total and regional adiposity and cognitive change in older adults: The Health, Aging and Body Composition (ABC) study. Arch Neurol 66, 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Pike CJ (2017) Sex and the development of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res 95, 671–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Paganini-Hill A, Henderson VW (1994) Estrogen deficiency and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in women. Am J Epidemiol 140, 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, Hendrix SL, Jones BN 3rd, Assaf AR, Jackson RD, Kotchen JM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wactawski-Wende J (2003) Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289, 2651–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Thal L, Lane DS, Fillit H, Stefanick ML, Hendrix SL, Lewis CE, Masaki K, Coker LH (2004) Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 291, 2947–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Coin A, Veronese N, De Rui M, Mosele M, Bolzetta F, Girardi A, Manzato E, Sergi G (2012) Nutritional predictors of cognitive impairment severity in demented elderly patients: the key role of BMI. J Nutr Health Aging 16, 553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zuccato C, Cattaneo E (2009) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurol 5, 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Johnson DK, Wilkins CH, Morris JC (2006) Accelerated weight loss may precede diagnosis in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 63, 1312–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, Kukull W (2012) Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 71, 266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Moga DC, Abner EL, Brouwer ES (2015) Dementia and “obesity paradox”: Is this for real or are we missing something? An epidemiologist’s perspective. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16, 78–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.