Abstract

Objectives

Candida albicans remains the most common aetiology of invasive candidiasis, leading to high morbidity and mortality. Nevertheless, the incidence of candidiasis due to non-C. albicans species, such as Candida parapsilosis, is increasing. Postantifungal effect (PAFE) is relevant for establishing dosage schedules in antifungal therapy, as the frequency of antifungal administration could change depending on PAFE. The aim of this study was to evaluate the PAFE of anidulafungin against C. albicans, Candida dubliniensis, Candida africana, C. parapsilosis, Candida metapsilosis and Candida orthopsilosis.

Material and methods

Twenty-one Candida strains were evaluated. Cells were exposed to anidulafungin for 1 h at concentrations ranging from 0.12 to 8 mg/L for PAFE studies. Time-kill experiments (TK) were conducted at the same concentrations. The experiments were performed using an inoculum of 1-5 x 105 cells/mL and 48 h incubation. Readings of PAFE and TK were done at 0, 2, 4, 6, 24 and 48 h.

Results

Anidulafungin was fungicidal against 2 out of 14 (14%) strains of C. albicans related species in PAFE experiments. Moreover, 2 mg/L of anidulafungin exerted a prolonged PAFE (≥ 33.6 h) against 13 out of 14 (93%) strains. Similarly, fungicidal endpoint was achieved against 1 out of 7 (14%) strains of C. parapsilosis complex, being PAFE prolonged (≥ 42 h) against 6 out of 7 (86%) strains.

Conclusions

Anidulafungin induced a significant and prolonged PAFE against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis and their related species.

Keywords: Postantifungal effect, anidulafungin, Candida

Abstract

Objetivos

Candida albicans continúa siendo la causa más frecuente de candidiasis invasiva; sin embargo, la incidencia de candidiasis causadas por especies diferentes a C. albicans, como Candida parapsilosis, está aumentando. El efecto postantifúngico (PAFE) es relevante para establecer pautas de dosificación en la terapia antifúngica, ya que la frecuencia de administración de los fármacos antifúngicos podría cambiar dependiendo del PAFE. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el PAFE de anidulafungina contra C. albicans, Candida dubliniensis, Candida africana, C. parapsilosis, Candida metapsilosis y Candida orthopsilosis.

Material y métodos

Se evaluaron 21 cepas de Candida. Para llevar a cabo los estudios PAFE, las células se expusieron durante 1 h a concentraciones entre 0,12 y 8 mg/L de anidulafungina. Las curvas de letalidad (TK) se obtuvieron empleando las mismas concentraciones. Los experimentos se realizaron utilizando un inóculo de 1-5 x 105 células/mL, durante 48 h de incubación. Las lecturas de PAFE y TK se realizaron a las 0, 2, 4, 6, 24 y 48 h.

Resultados

Anidulafungina, en los experimentos PAFE, fue fungicida contra 2 de 14 (14%) cepas de las especies relacionadas con C. albicans y ejerció un PAFE prolongado (≥ 33,6 h) contra 13 de 14 (93%) cepas (2 mg/L). El límite fungicida de anidulafungina se alcanzó contra 1 de 7 (14%) cepas del complejo C. parapsilosis, con un PAFE prolongado (≥ 42 h) contra 6 de 7 (86%) cepas.

Conclusiones

Anidulafungina produce un PAFE significativo y prolongado contra C. albicans y C. parapsilosis y las especies relacionadas con estas.

Palabras clave: Efecto postantifúngico, anidulafungina, Candida

INTRODUCTION

Invasive candidiasis is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among patients suffering from severe immunodeficiency. Although Candida albicans remains the most common aetiology, the incidence of candidiasis due to non-C. albicans species is increasing. Most Candida bloodstream infections are caused by C. albicans, Candida parapsilosis, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, and Candida krusei [1,2]. Moreover, C. albicans and C. parapsilosis have close-related species, such as Candida dubliniensis and Candida africana (C. albicans related species) or Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis (C. parapsilosis complex). Differences and variability in the prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of these species have been reported [3,4].

Postantifungal effect (PAFE) describes how long an antifungal drug continues acting after it has been removed. This effect depends on both the fungal species and antifungal drug, and it may be relevant for antifungal therapy, having clinical relevance for establishing dosage schedules. Echinocandins and amphotericin B (fungicidal drugs) exert prolonged PAFE against C. albicans while triazoles (fungistatic drugs) possess shorter PAFE. Theoretically, antifungal drugs with long PAFE will require less frequent administration than those with shorter PAFEs [5,6]. The aim of this study has been to evaluate the PAFE of clinically relevant concentrations of anidulafungin against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis related species.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Microorganisms. Twenty-one Candida clinical isolates and culture collection strains were studied (table 1). The clinical isolates were identified as previously described [7,8].

Table 1.

Anidulafungin MICs against strains from species related with C. albicans and C. parapsilosis

| Isolate | Origin | MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans NCPF 3153 | Reference | 0.03 |

| Candida albicans NCPF 3156 | Reference | 0.03 |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-101 | Blood | 0.06 |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-102 | Blood | 0.03 |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-103 | Blood | 0.03 |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-104 | Blood | 0.06 |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-105 | Blood | 0.06 |

| Candida dubliniensis NCPF 3949 | Reference | 0.06 |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-131 | Blood | 0.06 |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-132 | Blood | 0.06 |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-133 | Blood | 0.03 |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-135 | Blood | 0.03 |

| Candida africana UPV/EHU 97-135 | Vaginal | 0.03 |

| Candida africana ATCC 2669 | Reference | 0.06 |

| Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | Reference | 1 |

| Candida parapsilosis ATCC 90018 | Reference | 2 |

| Candida parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09-378 | Blood | 2 |

| Candida metapsilosis ATCC 96143 | Reference | 1 |

| Candida metapsilosis UPV/EHU 07-045 | Blood | 1 |

| Candida orthopsilosis ATCC 96139 | Reference | 1 |

| Candida orthopsilosis UPV/EHU 07-035 | Blood | 1 |

In vitro susceptibility testing. Anidulafungin (Pfizer SLU, Spain) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Further dilutions were done in standard RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Spain). Minimum concentrations that produce ≥ 50% growth reductions (MICs) after 24 h of incubation were determined according to the M27-A3, M27-S4 and M60 documents [9,10].

Time-kill procedures. Time-kill studies (TK) were performed out in microtiter plates in a computer-controlled microbiological incubator (BioScreen C MBR, LabSystems, Finland) in RPMI (200 µl) using an inoculum of 1-5 x 105 cells/ml, as previously described [11]. The concentrations assayed were 0.125, 0.5 and 2 mg/L for C. albicans related species, and 0.25, 2 and 8 mg/L for C. parapsilosis complex. Aliquots were removed from each well at 0, 2, 4, 6, 24 and 48 h, after dilution in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the samples were inoculated onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates. Colonies were counted after incubation of the plates (36 ± 1 ˚C) for 48 h. All experiments were performed in duplicate. The limit of quantification was 20 colony forming units (CFU).

Postantifungal effect. PAFE was evaluated as previously described [12-14]. After an incubation period of 1 h, anidulafungin was removed by serial washing in PBS and centrifuged at 2000 rpm x 10 min. Tested concentrations, incubations, sample collection times and inoculations onto SDA plates were the same as described for TK assay. PAFE was calculated according to the equation PAFE= T - C (T: time required to increase by 1 log the counts in treated culture; C: time required to increase by 1 log the counts following the last washing) [15].

Fungicidal activity was defined as a growth reduction ≥ 3 log (99.9%), and fungistatic activity, as a reduction < 3 log (< 99.9%) in CFU from the starting inoculum. The ratios of the log killing during PAFE assays to the log killing during TK assays were also calculated [16].

Statistical analysis. The differences in PAFEs among the anidulafungin different concentrations and species were evaluated by ANOVA (GraphPad Software, USA). A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Anidulafungin MICs are summarized in table 1. Anidulafungin (2 mg/L) exhibited a prolonged and significant PAFE (≥ 33.6 h) against most strains of C. albicans related species (13 out of 14, 93%) (table 2). Besides, prolonged PAFE (> 37.7 h) with ≤ 0.5 mg/L of anidulafungin was observed against 5 out 14 (36%) of these strains. In TK experiments, anidulafungin (2 mg/L) was fungicidal against 5 out of 14 (36%) strains of C. albicans related species. Fungicidal endpoint was achieved against 2 out of 14 (14%) strains of C. albicans related species in PAFE experiments (strains C. albicans UPV/EHU 99-101 and C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-135). This fungicidal effect was even achieved when 0.5 mg/L of anidulafungin was tested against strain C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-135. The mean value of PAFE/TK ratio was 52.61 (2 mg/L) for C. albicans related species. Although there were no significant differences between the PAFE against C. albicans, C. dubliniensis and C. africana, it could be observed that anidulafungin presented slightly higher PAFE than against C. dubliniensis or C. africana (table 2).

Table 2.

Reductions in starting inocula of Candida during TK and PAFE experiments and PAFE in hours against fourteen strains of species related with C. albicans

| Isolate | AND (mg/L) | Killing (log) | PAFE/TK killinga | PAFE (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK | PAFE | ||||

| Candida albicans NCPF 3153 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.2 | 85.11 | 2 |

| 0.5 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 41.69 | 20 | |

| 2 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 100 | > 44 | |

| Candida albicans NCPF 3156 | 0.12 | 1.35 | 0.15 | 6.31 | 0 |

| 0.5 | ≥ 4 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0 | |

| 2 | ≥ 4 | 2.05 | 1.12 | > 42 | |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-101 | 0.12 | 2.7 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0 |

| 0.5 | ≥ 4 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0 | |

| 2 | ≥ 4 | ≥ 4 | 100 | > 43 | |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-102 | 0.12 | 0.92 | 0.30 | 24 | 3.2 |

| 0.5 | 2.02 | 1.6 | 38.02 | > 39.1 | |

| 2 | ≥ 4 | 1.3 | 0.19 | > 39.1 | |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-103 | 0.12 | NAb | 0.1 | > 43 | |

| 0.5 | NA | 0.05 | 19 | ||

| 2 | 2.03 | 1.24 | 16.22 | > 43 | |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-104 | 0.12 | NA | 0.35 | > 42 | |

| 0.5 | NA | 0.44 | > 42 | ||

| 2 | 1.1 | 0.41 | 20.42 | > 42 | |

| Candida albicans UPV/EHU 99-105 | 0.12 | ≥ 4 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0 |

| 0.5 | ≥ 4 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0 | |

| 2 | ≥ 4 | 1.82 | 0.66 | > 42 | |

| Candida dubliniensis NCPF 3949 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 100 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0.57 | 0.92 | 100 | > 42 | |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-131 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | NA | NA | 2 | ||

| 2 | 0.54 | 1.16 | 100 | > 44 | |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-132 | 0.12 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | NA | 0.08 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 31.62 | > 42 | |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-133 | 0.12 | NA | 0.13 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 100 | 18 | |

| 2 | 0.72 | 1.03 | 100 | 18 | |

| Candida dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-135 | 0.12 | ≥ 4 | NA | 0 | |

| 0.5 | ≥ 4 | ≥ 4 | 100 | > 42 | |

| 2 | ≥ 4 | 1.32 | 0.21 | > 42 | |

| Candida africana ATCC 2669 | 0.12 | NA | 0.23 | 2.8 | |

| 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 100 | > 37.7 | |

| 2 | 0.15 | 0.4 | 100 | > 37.7 | |

| Candida africana UPV/EHU 97-135 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 100 | 0.7 |

| 0.5 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 95.5 | 2 | |

| 2 | 0.6 | 0.42 | 66.07 | > 33.6 | |

AND, anidulafungin; TK, time-kill; PAFE, postantifungal effect.

Ratio of the log killing during PAFE experiments to the log killing during TK experiments.

NA, not applicable (without any reduction in colony counts compared with the starting inoculum)

A significant and prolonged PAFE (≥ 42 h) against 6 out of 7 (86%) strains of C. parapsilosis complex was observed with 8 mg/L of anidulafungin (P < 0.05) (table 3), but fungicidal endpoint was achieved only against C. metapsilosis UPV/EHU 07-045. This concentration was fungicidal against 6 out 7 (86%) strains from the C. parapsilosis complex and fungistatic against 1 C. orthopsilosis, in TK experiments. The mean value of PAFE/TK ratio was 15.48 (8 mg/L) for C. parapsilosis complex. There were no significant differences between the PAFE of anidulafungin against C. parapsilosis, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis (table 3).

Table 3.

Reductions in starting inocula of Candida isolates during TK and PAFE experiments and PAFE in hours against seven strains of species related with C. parapsilosis

| Isolate | AND (mg/L) | Killing (log) | PAFE/TK killinga | PAFE (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK | PAFE | ||||

| Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | 0.25 | NAb | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | 0.88 | 0.11 | 16.98 | 0 | |

| 8 | ≥ 4 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 42 | |

| Candida parapsilosis ATCC 90018 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | NA | NA | 3.6 | ||

| 8 | ≥ 4 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 42 | |

| Candida parapsilosis UPV/EHU 09-378 | 0.25 | 0.15 | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 100 | 5.7 | |

| 8 | ≥ 4 | NA | 5.2 | ||

| Candida metapsilosis ATCC 96143 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | ≥ 4 | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | ≥ 4 | 2.36 | 2.29 | > 44 | |

| Candida metapsilosis UPV/EHU 07-045 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | 1.12 | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | ≥ 4 | ≥ 4 | 100 | > 44 | |

| Candida orthopsilosis ATCC 96139 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | 3.05 | NA | 2 | ||

| 8 | ≥ 4 | 2.67 | 4.68 | > 44 | |

| Candida orthopsilosis UPV/EHU 07-035 | 0.25 | NA | NA | 0 | |

| 2 | 1.73 | NA | 0 | ||

| 8 | 2.06 | 0.19 | 1.35 | 42 | |

AND, anidulafungin; TK, time-kill; PAFE, postantifungal effect.

Ratio of the log killing during PAFE experiments to the log killing during TK experiments.

NA, not applicable (without any reduction in colony counts compared with the starting inoculum)

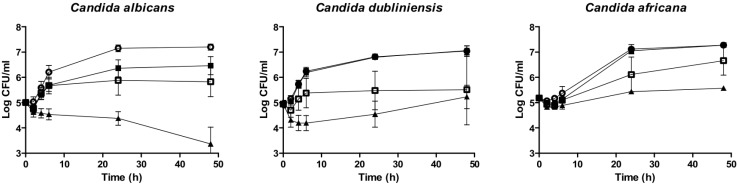

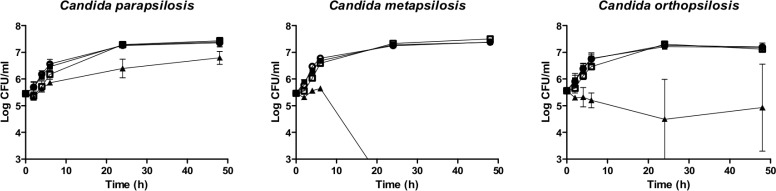

Mean anidulafungin PAFE against C. albicans related species (39.6 ± 26.81 h) (2 mg/L) did not differ from that one against C. parapsilosis complex (37.6 ± 14.32 h) (8 mg/L) (figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Mean time-kill curves from the PAFE assays against seven C. albicans, five C. dubliniensis and two C. africana strains. Each point represents the mean count ± standard deviation (error bars). Open circles (○): control; filled squares (■): 0.12 mg/L anidulafungin; open squares (□): 0.5 mg/L anidulafungin; and filled triangles (▲): 2 mg/L anidulafungin

Figure 2.

Mean time-kill curves from the PAFE assays against three C. parapsilosis, two C. metapsilosis and two C. orthopsilosis strains. Each point represents the mean count ± standard deviation (error bars). Open circles (○): control; filled squares (■): 0.25 mg/L anidulafungin; open squares (□): 2 mg/L anidulafungin; and filled triangles (▲): 8 mg/L anidulafungin

DISCUSSION

C. albicans and C. parapsilosis are the most frequent aetiological agents of invasive candidiasis in Spain and in many Mediterranean and Latin-American countries [1]. C. orthopsilosis and C. dubliniensis represent relatively frequent aetiological agents of invasive candidiasis, being in some institutions more prevalent than C. krusei [17]. To our knowledge, this is the first study that shows and compares the PAFE of anidulafungin against the emerging species C. dubliniensis, C. africana, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis. PAFE and TK experiments of anidulafungin against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis have not been widely evaluated and most studies included low numbers of isolates [5,12,15]. Moreover, this study provides a comparison among the in vitro activities of anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin [13,14].

Anidulafungin MICs were consistent with those reported in previous studies [8,18]. In the current study, anidulafungin exerted good fungicidal activity against most strains of C. parapsilosis complex but this activity was lower against C. albicans related species (with 8 mg/L and 2 mg/L, respectively). This discrepancy in the activity of the echinocandins against different species of Candida has been reported previously [11,12,16,19]; anidulafungin is considered fungicide against Candida but does not achieve this effect against all isolates. This effect depends on isolate, species, antifungal concentration and test conditions [5,11,19]. Similarly, Clancy et al. reported prolonged PAFE of caspofungin against C. albicans, C. parapsilosis and C. glabrata, but fungicidal activity was not observed in TK or PAFE experiments [16]. For this reason, it would be advisable to perform in vitro susceptibly testing, such as TK and PAFE studies, since killing curves are tools that provide much information about the antifungal activity.

Smith et al. [15] described fungicidal activity of anidulafungin in TK and in PAFE against C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis at similar concentrations. Moreover, Nguyen et al. [12] evaluated the anidulafungin PAFE against several Candida species, reporting fungicidal PAFE against the former species. However, we only observed fungicidal activity against C. parapsilosis in TK experiments, except for one strain of C. metapsilosis with fungicidal PAFE.

In the current study, there were not significant differences in anidulafungin activity among the species related to C. albicans and C. parapsilosis. However, we have observed previously statistically significant differences between species related to against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis in the duration of micafungin and caspofungin PAFEs, which were longer against C. albicans related species than against C. parapsilosis complex [13,14]. Anidulafungin is the echinocandin with greater PAFE against C. parapsilosis. Conversely, micafungin was the echinocandin that displayed the lowest PAFE against the C. parapsilosis complex. However, all echinocandins showed a similar PAFE against the C. albicans related species, with a slightly but non-significant higher PAFE with micafungin [13,14]. In PAFE experiments anidulafungin (≤ 2 mg/L) and micafungin (2 mg/L) achieved the fungicidal endpoint against 2 out 14 (14%) strains of C. albicans related species (C. albicans UPV/EHU 99-101, C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-135 and C. albicans UPV/EHU 99-102, and C. dubliniensis UPV/EHU 00-135, respectively). Caspofungin (2 mg/L) only achieved this endpoint against 1 out of 14 (7%) strains (C. albicans UPV/EHU 99-101). Only anidulafungin (8 mg/L) displayed a fungicidal PAFE against the C. parapsilosis complex (1 out 7, 14% strains, C. metapsilosis UPV/EHU 07-045) [13,14]. Fungal growth characteristics or binding affinities of each drug could be possible explanations for PAFE differences [12]. PAFE may have clinical relevance to the design of dosing regimens for antifungal agents, as those antifungal drugs with longer PAFEs may be administered less frequently than those ones with shorter PAFEs [5,20].

In conclusion, anidulafungin showed a significant and prolonged PAFE against the species closely related to C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, being the echinocandin with greater PAFE against C. parapsilosis complex. Although the clinical implications of in vitro killing and PAFE need further research, the current findings represent an initial step towards improving dosage regimen in clinical setting.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Consejería de Educación, Universidades e Investigación of Gobierno Vasco-Eusko Jaurlaritza [GIC15/78 IT990-16] and Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU) [UFI 11/25 and ESPDOC17/109 to S. G.-A.].

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the current manuscript, but declare the following: G.Q. has received research grants from Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Scynexis. G.Q. has served on advisory/consultant boards for Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Scynexis, and he has received speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Astellas Pharma, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Scynexis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Quindós G. Epidemiology of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis. A changing face. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014;31(1):42-8. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadeghi G, Ebrahimi-Rad M, Mousavi SF, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Razzaghi-Abyaneh M. Emergence of non-Candida albicans species: Epidemiology, phylogeny and fluconazole susceptibility profile. J Mycol Med. 2018;2851-8. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockhart SR, Messer SA, Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Geographic distribution and antifungal susceptibility of the newly described species Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis in comparison to the closely related species Candida parapsilosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(8):2659-64. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00803-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Messer SA, Moet GJ, Jones RN. Variation in Candida spp. distribution and antifungal resistance rates among bloodstream infection isolates by patient age: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008-2009). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68(3):278-83. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernst EJ, Klepser ME, Pfaller MA. Postantifungal effects of echinocandin, azole, and polyene antifungal agents against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(4):1108-11. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepak AJ, Andes DR. Antifungal pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;5(5):a019653. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda-Zapico I, Eraso E, Hernández-Almaraz JL, López-Soria LM, Carrillo-Muñoz AJ, Hernández-Molina JM, et al. Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility patterns of new cryptic species inside the species complexes Candida parapsilosis and Candida glabrata among blood isolates from a Spanish tertiary hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(10):2315-22. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pemán J, Cantón E, Quindós G, Eraso E, Alcoba J, Guinea J, et al. Epidemiology, species distribution and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of fungaemia in a Spanish multicentre prospective survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(5):1181-7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M60. Performance standards for antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast, 1st edition Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M27-A3 and M27-S4. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast and Fourth Informational Supplement. 2008-2012 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantón E, Espinel-Ingroff A, Pemán J, del Castillo L.. In vitro fungicidal activities of echinocandins against Candida metapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. parapsilosis evaluated by time-kill studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(5):2194-7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01538-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen KT, Ta P, Hoang BT, Cheng S, Hao B, Nguyen MH, et al. Anidulafungin is fungicidal and exerts a variety of postantifungal effects against Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. krusei isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(8):3347-52. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01480-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil-Alonso S, Jauregizar N, Eraso E, Quindós G. Postantifungal effect of micafungin against the species complexes of Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(7). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil-Alonso S, Jauregizar N, Eraso E, Quindos G. Postantifungal effect of caspofungin against the Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis clades. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;86(2):172-7. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith RP, Baltch A, Bopp LH, Ritz WJ, Michelsen PP. Post-antifungal effects and time-kill studies of anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin against Candida glabrata and Candida parapsilosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71(2):131-8. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clancy CJ, Huang H, Cheng S, Derendorf H, Nguyen MH. Characterizing the effects of caspofungin on Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida glabrata isolates by simultaneous time-kill and postantifungal-effect experiments. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(7):2569-72. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astvad KMT, Johansen HK, Roder BL, Rosenvinge FS, Knudsen JD, Lemming L, et al. Update from a 12-year nationwide fungemia surveillance: increasing intrinsic and acquired resistance causes concern. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56(4):10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01564-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaller MA, Espinel-Ingroff A, Bustamante B, Cantón E, Diekema DJ, Fothergill A, et al. Multicenter study of anidulafungin and micafungin MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for eight Candida species and the CLSI M27-A3 broth microdilution method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(2):916-22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02020-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gil-Alonso S, Jauregizar N, Cantón E, Eraso E, Quindós G. Comparison of the in vitro activity of echinocandins against Candida albicans, Candida dubliniensis, and Candida africana by time-kill curves. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;82(1):57-61. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oz Y, Kiremitci A, Dag I, Metintas S, Kiraz N. Postantifungal effect of the combination of caspofungin with voriconazole and amphotericin B against clinical Candida krusei isolates. Med Mycol. 2013;51(1):60-5. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.697198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]