Abstract

RNA polymerase II (Pol II) has an intrinsic fidelity control mechanism to maintain faithful genetic information transfer during transcription. 8-Oxo-guanine (8OG), a commonly occurring damaged guanine base, promotes misincorporation of adenine into the RNA strand. Recent structural work has shown that adenine can pair with the syn conformation of 8OG directly upstream of the Pol II active site. However, it remains unknown how 8OG is accommodated in the active site as a template base for the incoming ATP. Here, we used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate two consecutive steps that may contribute to the adenine misincorporation by Pol II. First, the mismatch is located in the active site, contributing to initial incorporation of adenine. Second, the mismatch is in the adjacent upstream position, contributing to extension from the mismatched bp. These results are supported by an in vitro transcription assay, confirming that 8OG can induce adenine misincorporation. Our simulations further suggest that 8OG forms a stable bp with the mismatched adenine in both the active site and the adjacent upstream position. This stability predominantly originates from hydrogen bonding between the mismatched adenine and 8OG in a noncanonical syn conformation. Interestingly, we also found that an unstable bp present directly upstream of the active site, such as adenine paired with 8OG in the canonical anti conformation, largely disrupts the stability of the active site. Our findings have uncovered two main factors contributing to how 8OG induces transcriptional errors and escapes Pol II transcriptional fidelity control checkpoints.

Keywords: RNA polymerase II, DNA damage, transcription, mutagenesis mechanism, molecular dynamics, 8-oxo-guanine (8OG), transcriptional bypass, nucleotide misincorporation, transcriptional fidelity

Introduction

DNA damage inevitably occurs during any organisms' life, and it can disrupt or alter the information encoded in its sequence. One of the most common types of DNA damage encountered in humans is the change of a guanine base to 8-oxo-guanine (8OG)4 under oxidative stress (1). This type of damage is known to be mutagenic and can be bypassed by DNA polymerases during replication (2). To ensure the stability of the genetic information over the lifetime of an organism, cells possess elaborate repair systems, base excision repair being a primary pathway for removing 8OG from DNA (3).

RNA polymerase II (Pol II) employs several mechanisms for maintaining the high fidelity of transcription, intrinsic proofreading being a notable example (4–6). Previous experiments (7–10) show that Pol II can incorporate a mismatched adenine nucleotide opposite an 8OG lesion, potentially changing the encoded protein sequence. As demonstrated in vitro by Kuraoka et al. (8), Pol II supports the bypass of 8OG lesion with both adenine misincorporation and correct cytosine insertions into the RNA strand. Furthermore, in vivo experiments performed by Brégeon et al. (10) provide evidence that such transcriptional mutagenesis can cause production of mutant proteins and subsequent phenotypic changes in mammalian cells. A recent work by Damsma and Cramer (7) approached the 8OG bypass by Pol II with both biochemical and structural methods. Their in vitro transcription assays revealed that the overall misincorporation percentage of adenine compared with cytosine opposite 8OG is on the same order of magnitude. In the same study, Damsma and Cramer (7) obtained two crystal structures of a Pol II elongation complex with 8OG damaged DNA nucleotide in the upstream of the active site (−1 site). The first structure revealed that 8OG adopts an unusual syn conformation when located opposite a mismatched adenine forming a Hoogsteen bp. The second structure displayed 8OG matched with a cytosine, where 8OG retains the canonical anti conformation forming a Watson-Crick bp. In both of these structures, the DNA base in the active site is an adenine, and the RNA 3′ end matched uridine is frayed.

Although the previous structural study (7) provides great insights into how the addition of the next RNA nucleotide is allowed after ATP misincorporation with 8OG template, how 8OG is accommodated in the Pol II active site (+1 site) is still unclear. Moreover, how 8OG serves as a template base to support both erroneous (ATP) and error-free (CTP) incorporation remains largely elusive. Using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we study the dynamics of the complex and intermediate conformations not captured in the previous structural studies (7), analyzing key forces contributing to the misincorporation. MD simulations have been shown to be a valuable tool to model dynamics of Pol II transcriptional complex (11–17).

Here, we first use an in vitro transcription assay to show that Pol II can incorporate a mismatched adenine opposite the 8OG in the coding DNA strand. We then perform all-atom MD simulations to investigate how 8OG promotes misincorporation of adenine in Pol II transcription. We examine two key steps: when 8OG is in the active site (+1 site), and when it is in the upstream (−1 site). We find that the stability of the canonic bp C:G(anti) does not differ significantly from C:8OG(anti), suggesting that both G and 8OG can support CTP incorporation. As for ATP misincorporation, we found that only 8OG in the noncanonical syn conformation 8OG(syn), but not 8OG(anti) or G(syn or anti), is able to stabilize ATP bound in the active site, leading to comparable stability with the Watson-Crick bp: CTP:8OG(anti). Finally, we found that the A:8OG(syn) bp is also stable at the upstream −1 site, which, together with a stable active site, allows the extension of the RNA strand. In contrast, other mismatched bp at upstream −1 site (A:8OG(anti), A: dG(syn), and A:dG(anti)) are all unstable, subsequently compromising the integrity of the active site.

Results and discussion

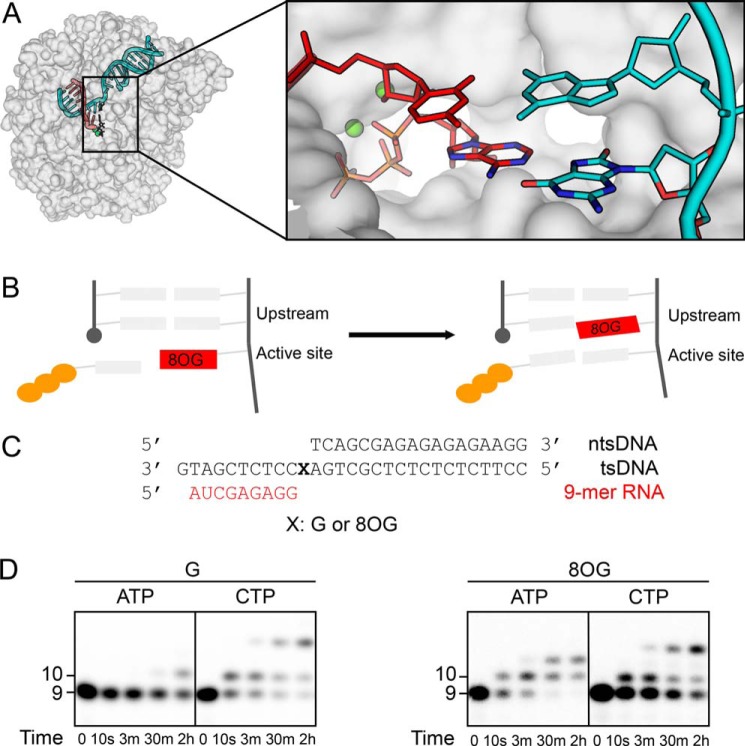

First, we performed the in vitro transcription experiment to confirm that both ATP and CTP can be incorporated opposite 8OG in the template DNA, whereas an undamaged dG does not allow for efficient ATP incorporation (Fig. 1, C and D). Indeed, we found that for 8OG, both ATP and CTP can be incorporated. In contrast, for undamaged dG template, only CTP can be efficiently incorporated, whereas a very small amount of ATP can only be incorporated after prolonged incubation (2 h) (Fig. 1D). This is consistent with previously described nontemplate adenine insertion that coincides with prolonged Pol II pausing, known as the A-rule (31).

Figure 1.

Two possible fidelity controls that 8OG could escape to induce transcription errors. A, overview of the modeled RNA Pol II with bound DNA, RNA, and an NTP molecule. DNA is shown in cyan color; RNA is shown in red. Structure of the active site is on the right, showing an ATP:8OG(syn) bp and an upstream bp. B, schematic view of the systems studied: 8OG before mismatch incorporation and after. C, the scaffold used in the transcription assay. D, error-prone and error-free transcriptional bypass of 8OG. The 8OG template can support both effective CTP incorporation and ATP misincorporation, whereas dG template only favors CTP incorporation. Time point of each lane is 0 (without ATP or CTP addition), 10 s, 3 min, 30 min, and 2 h.

To understand how 8OG is recognized and bypassed, we further examined how the ATP:8OG mismatch is accommodated and stabilized in the active site of Pol II elongation complex (Fig. 1A). Several factors could contribute to this favorable misincorporation of ATP opposite 8OG: stable hydrogen bonding between ATP and 8OG, favorable interactions between the ATP:8OG bp and neighboring Pol II residues, and a good shape complementarity of the bp to the active site. We perform extensive MD simulations of Pol II elongation complex with an NTP bound in the active site (eight simulation systems with aggregated 2 μs MD simulations) to analyze how these factors contribute to adenine misincorporation opposite an 8OG. Furthermore, we set up another eight simulation systems to investigate how the A:8OG mismatch in the upstream (−1 site) may impact the incorporation of the next nucleotide (Fig. 1B). All 16 systems are stable in our MD simulations with C-α RMSD deviating less than 4 Å from the starting configuration, and the RMSD curves plateau at ∼10 ns (Figs. S3 and S4). Therefore, we chose the part of our MD simulation after 10 ns of simulation time to perform subsequent analysis and report the results in the remaining part of the manuscript.

Only syn conformation of 8OG allows for a stable mismatched ATP bound in the active site

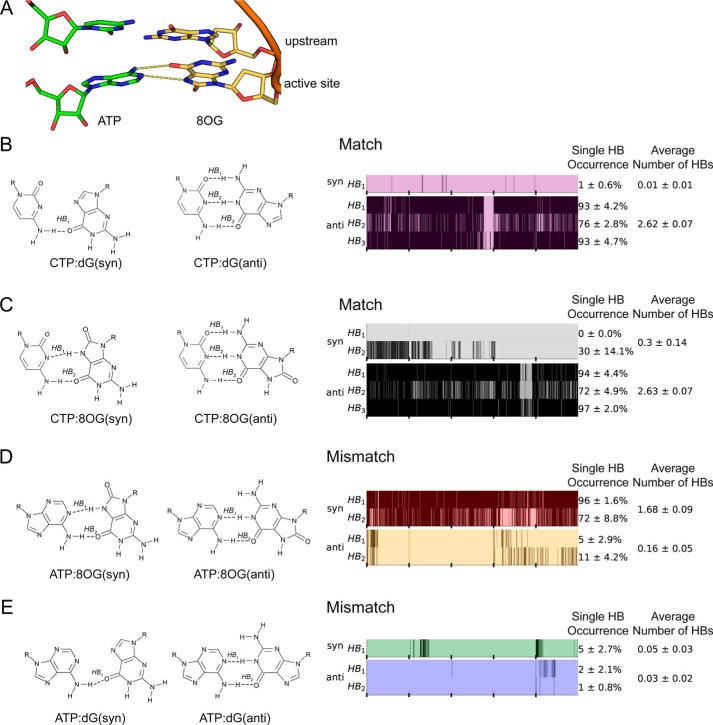

To understand how 8OG can promote ATP misincorporation when located at the active site, we first compare the stability of hydrogen bonds between bases of ATP or CTP and either the damaged 8OG template or the undamaged template (dG). For ATP misincorporation opposite the damaged template, our simulations demonstrate that an ATP:8OG(syn) bp in the active site of Pol II (Fig. 2A) forms on average close to two hydrogen bonds, whereas ATP:8OG(anti) forms zero (see the panel displaying average number of HBs in Fig. 2D). Moreover, hydrogen bonds of ATP:8OG(syn) pair have a lifetime comparable with that of the canonical Watson-Crick CTP:dG(anti) bp (see the panel displaying single HB occurrence in Fig. 2, B and C); up to 96% of the trajectory had at least one hydrogen bond present, indicating that the bp is stable throughout our simulations. These results suggest that the damaged guanine base can stabilize the mismatched ATP substrate via adopting a syn orientation, which may subsequently lead to misincorporation. Furthermore, we show that the hydrogen bonding of undamaged guanine is negligible in both anti and syn orientation with a mismatched ATP (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Hydrogen bonding of the bp in the active site of Pol II. A, structure of the RNA–DNA duplex and the NTP paired in the active site. Dashed lines depict hydrogen bonds in the studied bp. B, hydrogen bonds formed by the matched bp in the active site CTP:dG. C, hydrogen bonds formed by the matched bp in the active site CTP:8OG. D, hydrogen bonds formed by the mismatched bp in the active site ATP:8OG. E, hydrogen bonds formed by the mismatched bp in the active site ATP:dG. Each set of MD simulations contained different bp in the active site. B–E, bp structure is shown on the left panel; the right panel shows hydrogen bond maps. Hydrogen bond maps display the hydrogen bonds occurring over the course of the simulation. Vertical black bars indicate that a hydrogen bond is present in the snapshot of the simulation; ticks on the x-axis denote individual trajectories. Single HB occurrence reflects the total fraction of time the specific bond was present in the simulation. Average number of HBs is calculated for the total number of hydrogen bonds formed by the bp. Error bars were calculated as S.D. by bootstrapping five independent MD trajectories five times with replacement for each system.

For the matched CTP substrate, we found that hydrogen bonding of CTP:8OG(anti) is indistinguishable from CTP:dG(anti), both forming on average close to three hydrogen bonds, but syn conformations of the dG and 8OG do not form stable hydrogen bonds with CTP (Fig. 2, B and C). These results indicate that 8OG DNA damage still allows matched incorporation with nearly unchanged stability of base pairing in the active site.

To understand whether other factors may contribute to stability of the bp in the active site in addition to hydrogen bonds, we also examine the contribution of steric interactions. We found that steric interactions indeed play a role in controlling the higher stability of bp ATP:8OG(syn) over ATP:8OG(anti). The purine:purine pair in anti conformation requires a larger distance between the backbone atoms, compared with a canonical pyrimidine:purine pair, which renders their shape to be too large to fit into the active site. To quantitatively analyze the positioning of ATP in the active site, we also inspect the vertical and lateral positioning of the ribose moiety of ATP relative to the 3′ RNA nucleotide and the DNA nucleotide in the active site (C1′–C1′ distance distributions between the corresponding nucleotides) (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, ATP:8OG(syn) (Fig. 3D), CTP:8OG(anti) (Fig. 3C), and CTP:dG(anti) (Fig. 3B) show the great stability of the bp, whereas other bp all deviate significantly from the starting geometry and display diverse populations of several states which can promote NTP dissociation. In particular, for ATP:dG(syn and anti) and ATP:8OG(anti), higher unpaired populations (see basin 2, Fig. 3, D and E) were observed compared with ATP:8OG(syn). We expect that this distorted active site state may lead to eventual ATP dissociation from Pol II active site.

Figure 3.

NTP stability in the active site of Pol II. A, structure of the RNA–DNA duplex and the NTP paired in the active site. B, CTP paired with different conformations of dG. C, CTP paired with different conformations of 8OG. D, ATP paired with different conformations of 8OG. E, ATP paired with different conformations of dG. Each set of MD simulations contained different bp in the active site. B–E, demonstrate the NTP stability, shown as normalized distributions of distances over the five trajectories of the specific system setup. Distance d1 is the distance between C1′ atom of the NTP and the coding DNA nucleotide in the active site; d2 is the distance between C1′ atoms of ATP and the upstream nucleotide. D and E, basins 1 and 2 correspond to a correct bp and a disrupted one, respectively.

The above results show that only ATP:8OG(syn) is stable in the active site because of persistent hydrogen bonds, whereas other systems, including ATP:8OG(anti), ATP:dG(syn), and ATP:dG(anti) are unable to stabilize ATP in the active site. Moreover, we did not observe any significant differences between the matched CTP:8OG and CTP:dG. Finally, we also examined the specific geometric parameters implied by the SN2 chemical reaction mechanism for the reacting atoms and the leaving group. We find that reaction geometry criteria critical for catalysis do not reflect any significant contribution to nucleotide discrimination, and no dissociation events of the triphosphate moiety bound to magnesium ions were observed in any of our simulations (see Fig. S5). Altogether, these observations indicate that the damaged 8OG in the active site allow both matched CTP incorporation and mismatched ATP incorporation via ATP:8OG(syn).

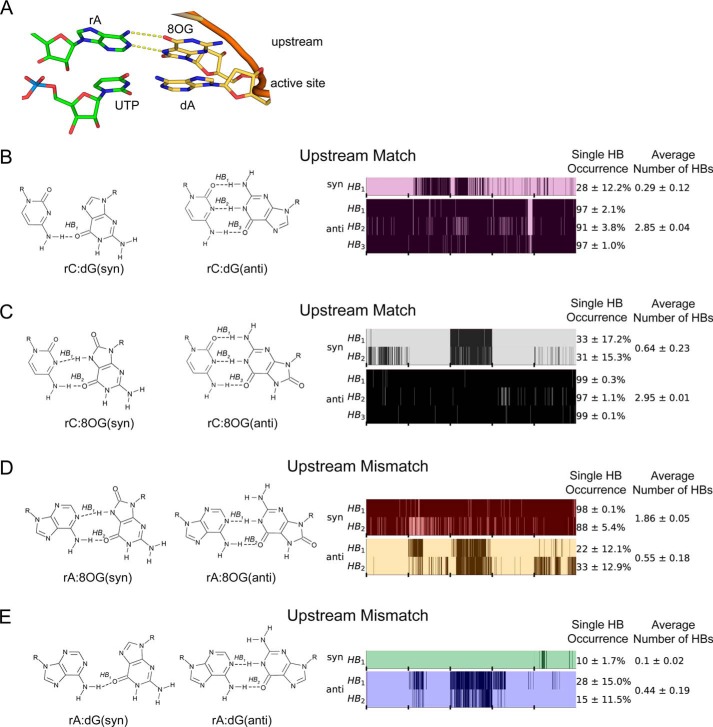

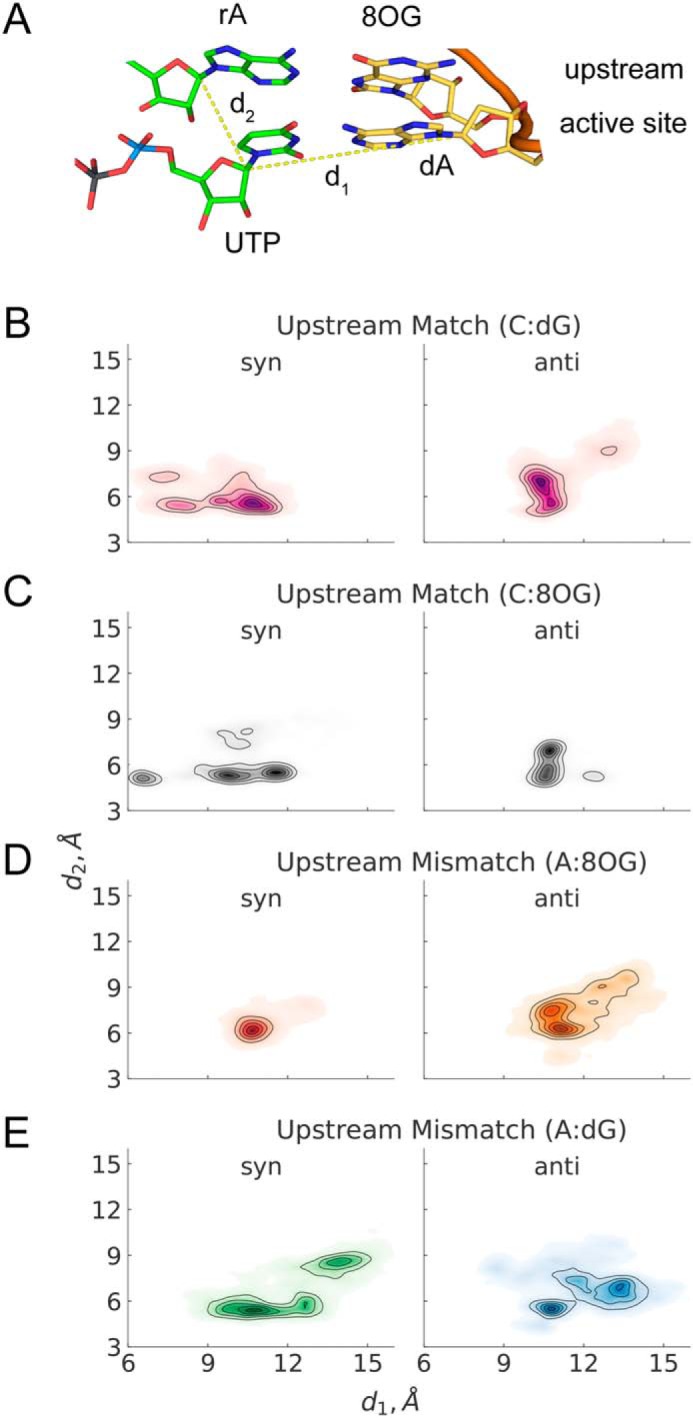

Only rA:8OG(syn) mismatch in the upstream −1 site leads to a stable active site

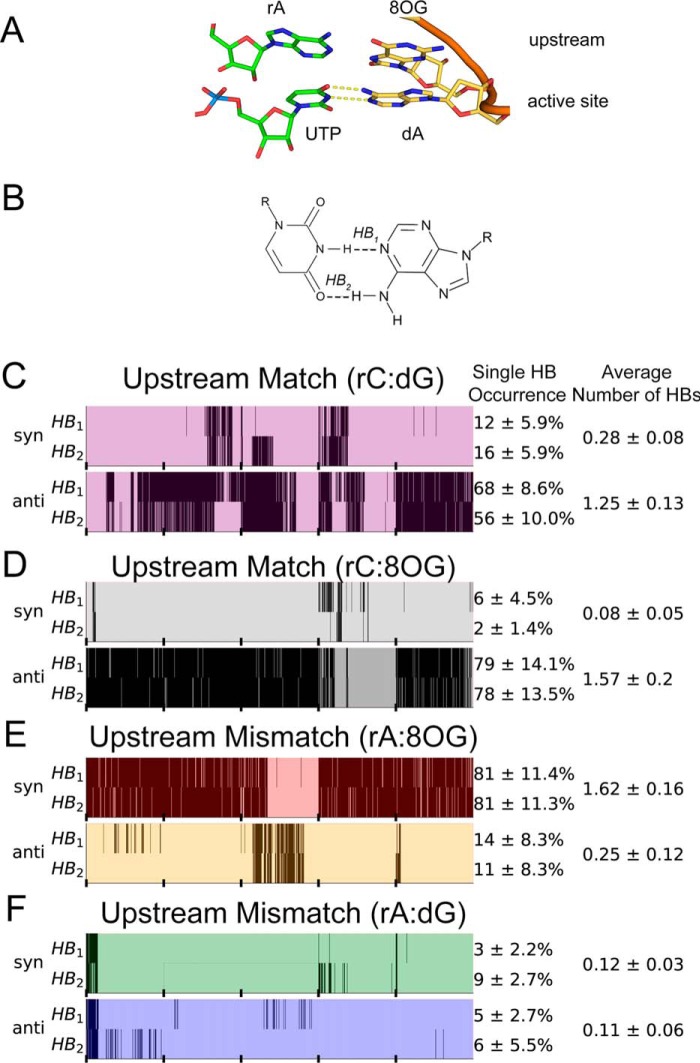

To investigate how rA:8OG mismatch at upstream position affects RNA extension, we first examine the stability of mismatched rA:8OG pair at −1 position (Fig. 4A). We found that rA:8OG(syn) is the only stable mismatched bp, forming on average 1.86 hydrogen bonds in our MD simulations (Fig. 4D). Even though the mismatched rA:8OG(syn) forms one less hydrogen bond compared with the matched rC:8OG(anti) and rC:dG(anti) systems (Fig. 4, B and C), the individual hydrogen bonds in the mismatched rA:8OG(syn) bp are stable and present in the majority of MD conformations (98 and 88% for each of the two hydrogen bonds) (see Fig. 4D). Overall, the hydrogen bonds of these bp in −1 site are substantially more stable than those formed in the active site (+1 site). In sharp contrast, for the case of rA:8OG(anti) mismatch (Fig. 4D) as well as rA:dG(anti) (Fig. 4E), one of the upstream bases becomes dislodged from the plane of the bp (Fig. 5), which may be because the RNA–DNA duplex structure is confined by the Pol II. As this out-of-plane base competes for hydrogen bonding with the base in the active site on the opposite strand, it may push the base on the same strand downstream and lead to instability of the active site. These observations suggest a profound effect of the −1 upstream mismatch on the bp of the incoming NTP with its template base at the active site.

Figure 4.

Hydrogen bonding of different bp upstream of the active site of Pol II. A, structure of the RNA–DNA duplex and the NTP paired in the active site. Dashed lines depict hydrogen bonds in the studied bp. B, hydrogen bonds formed by the matched bp rC:dG. C, hydrogen bonds formed by the matched bp rC:8OG. D, hydrogen bonds formed by the mismatched bp rA:8OG. E, hydrogen bonds formed by the mismatched bp rA:dG. Refer to Fig. 2 for the description of hydrogen bond maps shown on B–E. MD simulations analyzed here contained different bp in the −1 upstream position, including the rA:8OG mismatch, whereas the active site contained the canonic UTP:dA bp in all systems.

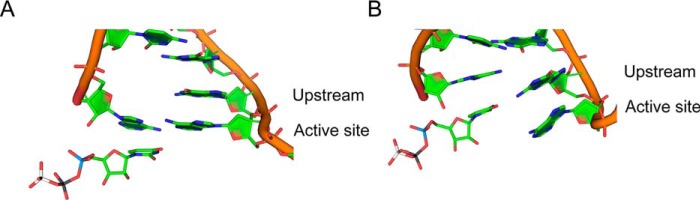

Figure 5.

Snapshots of rA:dG(anti) mismatch in the upstream of the active site, showing two types of upstream nucleotide dislocations disrupting base pairing in the active site. A, the 3′ RNA nucleotide competes for hydrogen bonding with the DNA nucleotide in the active site. B, the DNA nucleotide in the upstream competes for hydrogen bonding with the NTP bound in the active site.

Based on the above observation, we then systematically evaluated how different bp in the upstream −1 site may impact the UTP:dA matched bp in the active site as shown in Fig. 6A and B. We found that only the mismatched rA:8OG(syn) system in the upstream allows for stable hydrogen bonding between UTP and dA in the active site (Fig. 6E). When other mismatches including rA:8OG(anti), rA:dG(anti), and rA:dG(syn) are present in the upstream −1 site, we detect almost no hydrogen bonds between UTP and dA in the active site, thus likely preventing efficient extension of RNA (Fig. 6, E and F). We also examined the impact of uncommon syn orientations of the upstream (−1 site) DNA base in the matched systems on the active site stability. As expected, the syn orientation of the upstream DNA base leads to unstable base pairing in the −1 upstream site, subsequently disrupting base pairing in the active site in both undamaged (rC:dG(syn); Fig. 6C) and damaged systems (rC:8OG(syn); Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Hydrogen bonding of the canonic UTP:dA bp in the active site of Pol II. A, structure of the RNA–DNA duplex and the NTP paired in the active site. The mismatch is upstream of the active site. Dashed lines depict hydrogen bonds in the studied bp. B, hydrogen bonding of the UTP:dA bp occupying the active site. C, the −1 upstream site contains an rC:dG bp. D, the −1 upstream site contains an rC:8OG bp. E, the −1 upstream site contains an rA:8OG bp. F, the −1 upstream site contains an rA:dG bp. C–F, MD simulations considered here contained different bp in the −1 upstream position, whereas the active site contained the canonic UTP:dA bp in all systems. Refer to Fig. 2 for explanation of the hydrogen bond maps shown on C–F.

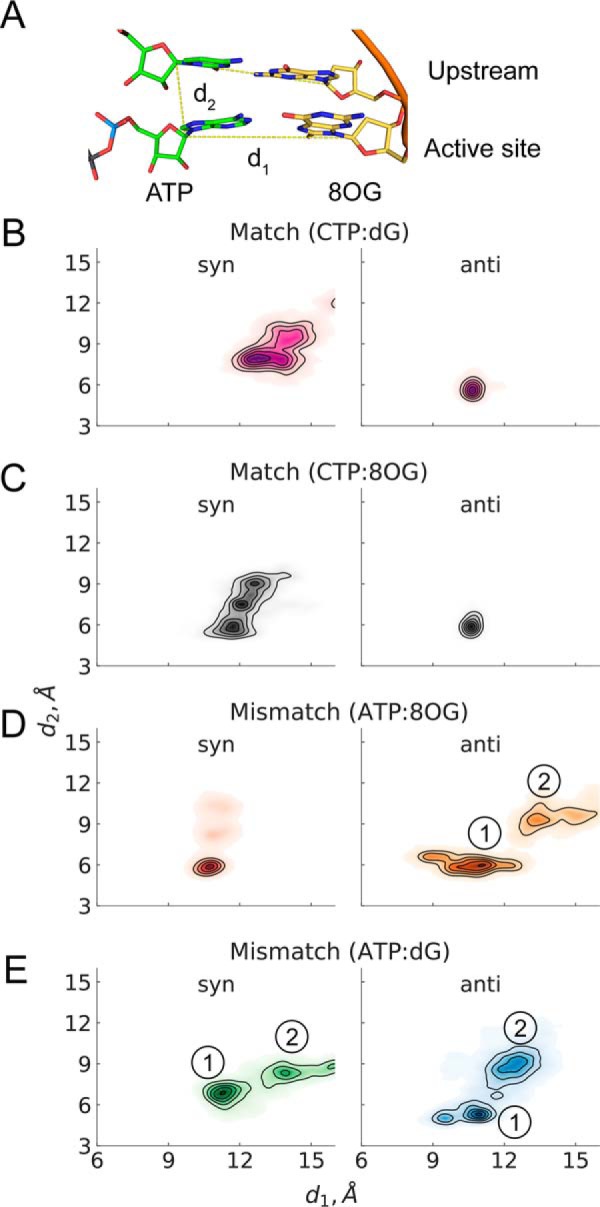

We investigated whether disruption of hydrogen bonding in the active site bp coincides with lateral and vertical positioning stability of the substrate. To achieve this, we examine the distributions of C1′–C1′ distances between the UTP and the template DNA nucleotide in the active site (d1) and between the UTP and the 3′ terminal nucleotide in the RNA strand (d2) (Fig. 7A). We found that the most stable UTP positioning in the active site corresponds to a matched bp in the upstream (rC:dG(anti) and rC:8OG(anti)) (see Fig. 7, B and C); the mismatched rA:8OG(syn) also leads to comparable stability (Fig. 7D). All other systems, including A:dG mismatch (Fig. 7E), display substantial deviations from the starting conformation. These results suggest that stacking with the upstream base alone cannot account for UTP stability in the active site and that stable base pairing at the upstream position is critical to the stability of the active site and further catalysis.

Figure 7.

UTP stability in the active site of Pol II paired with dA, with the mismatch located in the −1 upstream position. A, structure of the RNA–DNA duplex in the active site and upstream of the active site. The dashed lines show the studied distances, d1 and d2. B, the −1 upstream site is occupied by rC:dG. C, the −1 upstream site is occupied by rC:8OG. D, the −1 upstream site is occupied by rA:8OG. E, the −1 upstream site is occupied by rA:dG. Each set of MD simulations contained different bp in the −1 upstream position, whereas the active site contained the canonic UTP:dA bp in all systems. Refer to Fig. 3 for the description of the distributions on B–E.

In addition to the positioning of the substrate, several geometry features in the active site play an important role in catalytic nucleotide incorporation such as the distance between reactive atoms (i.e. distance between O3′ on the terminal RNA nucleotide and Pα on the substrate) and the angle of the nucleophilic attack. As shown in Fig. S6, these geometry features are well maintained for rA:8OG(syn), allowing for the RNA extension after the misincorporation.

Here we simulated two consecutive steps in the process of adenine misincorporation with 8OG DNA damage, when the mismatch is located in the active site of Pol II, and at −1 upstream site. When 8OG is in the active site, we found that the syn conformation can stabilize a mismatched substrate (ATP:8OG(syn)), whereas the canonical anti orientation disrupts the active site (ATP:8OG(anti)). In particular, the hydrogen bonding stability of the ATP:8OG(syn) bp is much higher than that of ATP:8OG(anti). Moreover, the ATP:8OG(syn) has a better steric fit to the active site compared with ATP:8OG(anti). When 8OG is present in the upstream (−1 site), we found a similar pattern: rA:8OG(syn) is stable, whereas rA:8OG(anti) is unstable because of the loss of base pairing hydrogen bonds and poor steric fit. In the latter case, the nucleotide displaced from the −1 site can further induce steric clashes with the active site bp, disrupting it, thus preventing RNA extension. Finally, the instability of rA:8OG(anti) in both active site and upstream position suggest that anti to syn conversion of 8OG must occur before the damaged nucleotide enters the active site. Our work agrees with and complements the previous structural studies (7) by showing how the ATP:8OG(syn) mismatch is accommodated in the active site and demonstrating why dG/8OG in the anti conformation can prohibit adenine misincorporation.

Conclusion

In this work we performed MD simulations to systematically investigate how RNA Pol II recognizes and bypasses 8OG in an error-prone and error-free manner. In particular, we explained why 8OG, but not dG, favors ATP misincorporation. We found two major factors contribute to 8OG bypass during transcription. First, the stable positioning of the NTP in the active site, is supported by hydrogen bonding with the DNA base in the active site. Second, the stability of the bp in the −1 upstream site has a major effect on the stability of the bp in the active site, with unstable bp upstream prohibiting RNA extension. We discover that rA:dG and rA:8OG mismatches with the DNA base in anti conformation cannot be accommodated in the upstream without severe disruptions of the active site, which would prevent RNA extension. Our simulation results agree well with our in vitro transcription experiments that demonstrate incorporation of both ATP and CTP opposite 8OG, whereas predominantly CTP is incorporated opposite an undamaged dG, not ATP.

Materials and methods

System setup

The initial structure of the Pol II transcription complex was taken from the X-ray structure of Pol II elongation complex (PDB ID 2E2H) (18). To model the 8OG in the upstream of the active site, we adopted the nucleic acid conformation and sequence from previous structures with PDB ID 3I4M and 3I4N (7). Furthermore, we improved the conformation of the closed trigger loop (see supporting Note S1 and Fig. S1). The 3′ RNA nucleotide was removed, a UTP molecule was placed in the catalytically active geometry in the active site and the base was positioned to produce a Watson-Crick bp with adenine in the coding DNA strand (Fig. S2). The 5′ RNA nucleotide and the 3′ template DNA nucleotide were removed to ensure that the RNA–DNA duplex length is the same in all systems. To model the 8OG DNA damage in the active site, the same Pol II complex structure was used but the whole nucleic acid sequence was shifted downstream and the last downstream DNA bp was removed to preserve the overall length of the nucleic acid. An NTP molecule was then placed in the active site and the bp was positioned to produce optimal hydrogen bonding.

Following the procedure described above, we constructed structures of the Pol II elongation complex with a closed trigger loop and the damaged base (8OG) located either in the active site (+1 site) or in the upstream position (−1 site). For 8OG located at the active site, we setup eight initial structures including four mismatched systems: ATP:8OG in syn conformation (ATP:8OG(syn)), ATP:8OG(anti), ATP:dG(syn), and ATP:dG(anti) and four matched systems: CTP:8OG(syn), CTP:8OG(anti), CTP:dG(syn), and CTP:dG(anti). For 8OG located at the upstream position, we also set up eight corresponding systems. Altogether, we constructed 16 simulation systems to elucidate how Pol II bypasses the misincorporation induced by 8OG DNA damage.

MD simulation details

Amber14SB (19) force field with OL15 (20) modification was used to conduct all-atom MD simulations using GROMACS 5.0.4 software (21). Because the force field parameters for ATP and UTP are missing in Amber14SB force field, we used the standard procedure to obtain them. In particular, partial charges were obtained by the RESP method (22) based on the Hartree-Fock calculations with a 6–31g* basis implemented in the Gaussian 09 software (23); other force field parameters were obtained from the Amber14SB force field. In our MD simulations, long-range electrostatic interactions were computed by particle mesh Ewald method (24), and nonbonded interactions were cut off at 12 Å. A velocity-rescaling thermostat with coupling constant of 0.1 ps was used to couple the system to a heat bath with a temperature of 289 K (25), and a Berendsen algorithm with 0.5 ps coupling time (26) was applied for the barostat. The protein complex was positioned 12 Å away from the dodecahedral cell borders and ∼122,000 water molecules were added, and then 71 water molecules were replaced by sodium ions to make the system neutral. The total atom count was ∼420,000 atoms. A time step of 2 femtoseconds was chosen for all MD simulations.

After an initial energy minimization with a gradient descent algorithm for 5000 steps, a 1 ns NVT MD simulation was performed with position restraints on all the heavy atoms, which was followed by another 1 ns position-restrained NPT simulation. For production runs, we performed five independent 50-ns MD simulations with different initial velocities for each of our 16 systems. Altogether, the accumulated simulation time reached 4 μs. We saved snapshots of MD simulation trajectories every 100 ps for subsequent data analysis.

Hydrogen bonding was calculated using the analysis tools of GROMACS 5.0.4 package, RMSD, and other parameters used in the analysis were calculated using MDTraj v. 1.6.7 library (27). Visualization of structures was performed in PyMOL software (28).

In vitro transcription assay

Purification of yeast RNA polymerase II and preparation of 32P-labeled miniscaffold was performed as described previously (29, 30). For the transcription assay, Pol II and miniscaffold in elongation buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 40 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm DTT) was preincubated for 10 min at room temperature to assemble the elongation complex. Reaction was started by adding the same volume of elongation complex to ATP or CTP. Final concentration of each component was 20 nm scaffold, 120 nm Pol II, 50 μm ATP or CTP in elongation buffer. Reaction mixture was added to quench-loading buffer (90% formamide, 50 mm EDTA, 0.05% xylene cyanol, and 0.05% bromphenol blue) with the volume ratio of 1:4, to stop the reaction at each time point. After denaturing by incubating the mixture for 10 min at 95 °C, results were analyzed in 12% of denaturing urea/TBE PAGE.

Author contributions

K. A. K. data curation; K. A. K. formal analysis; K. A. K., C. K. M. T., and J. O. investigation; K. A. K., C. K. M. T., and J. O. visualization; K. A. K., F. P.-A., C. K. M. T., and J. O. methodology; K. A. K., F. P.-A., C. K. M. T., and J. O. writing-original draft; K. A. K., D. W., and X. H. writing-review and editing; D. W. and X. H. supervision; X. H. conceptualization; X. H. funding acquisition; X. H. project administration.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Hong Kong Ph.D. Fellowship Scheme No. PF16-06144 (K. K.). This work was also supported by Hong Kong Research Grant Council HKUST C6009-15G, 16302214, 16307718, and AoE/P-705/16 (to X. H.); Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee Grant JCYJ20170413173837121 (to X. H.); Guangzhou Science Technology and Innovation Commission Grant 201704030116 (to X. H.); and Innovation and Technology Commission Grant ITC-CNERC14SC01 (to X. H.). This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM102362 (to D. W.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S6 and Notes S1 and S2.

- 8OG

- 8-oxo-guanine

- Pol II

- RNA polymerase II

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation

- HB

- hydrogen bond.

References

- 1. Ames B. N. (1989) Endogenous oxidative DNA damage, aging, and cancer. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 7, 121–128 10.3109/10715768909087933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brieba L. G., Eichman B. F., Kokoska R. J., Doublié S., Kunkel T. A., and Ellenberger T. (2004) Structural basis for the dual coding potential of 8-oxoguanosine by a high-fidelity DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 23, 3452–3461 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Loon B., Markkanen E., and Hübscher U. (2010) Mini-review oxygen as a friend and enemy: How to combat the mutational potential of 8-oxo-guanine. DNA Repair 9, 604–616 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thomas M. J., Platas A. A., and Hawley D. K. (1998) Transcriptional fidelity and proofreading by RNA polymerase II. Cell 93, 627–637 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81191-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu L., Wang W., Chong J., Shin J. H., Xu J., and Wang D. (2015) RNA polymerase II transcriptional fidelity control and its functional interplay with DNA modifications. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 50, 503–519 10.3109/10409238.2015.1087960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scicchitano D. A., Olesnicky E. C., and Dimitri A. (2004) Transcription and DNA adducts: What happens when the message gets cut off? DNA Repair 3, 1537–1548 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Damsma G. E., and Cramer P. (2009) Molecular basis of transcriptional mutagenesis at 8-oxoguanine. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31658–31663 10.1074/jbc.M109.022764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuraoka I., Endou M., Yamaguchi Y., Wada T., Handa H., and Tanaka K. (2003) Effects of endogenous DNA base lesions on transcription elongation by mammalian RNA polymerase II. Implications for transcription-coupled DNA repair and transcriptional mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7294–7299 10.1074/jbc.M208102200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tornaletti S., Maeda L. S., Kolodner R. D., and Hanawalt P. C. (2004) Effect of 8-oxoguanine on transcription elongation by T7 RNA polymerase and mammalian RNA polymerase II. DNA Repair 3, 483–494 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brégeon D., Peignon P.-A., and Sarasin A. (2009) Transcriptional mutagenesis induced by 8-oxoguanine in mammalian cells. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000577 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang X., Wang D., Weiss D. R., Bushnell D. A., Kornberg R. D., and Levitt M. (2010) RNA polymerase II trigger loop residues stabilize and position the incoming nucleotide triphosphate in transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 15745–15750 10.1073/pnas.1009898107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Da L. T., Pardo-Avila F., Xu L., Silva D. A., Zhang L., Gao X., Wang D., and Huang X. (2016) Bridge helix bending promotes RNA polymerase II backtracking through a critical and conserved threonine residue. Nat. Commun. 7, 11244 10.1038/ncomms11244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Da L.-T., Wang D., and Huang X. (2012) Dynamics of pyrophosphate ion release and its coupled trigger loop motion from closed to open state in RNA polymerase II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2399–2406 10.1021/ja210656k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang L., Pardo-Avila F., Unarta I. C., Cheung P. P.-H., Wang G., Wang D., and Huang X. (2016) Elucidation of the dynamics of transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II using kinetic network models. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 687–694 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Unarta I. C., Zhu L., Tse C. K. M., Cheung P. P.-H., Yu J., and Huang X. (2018) Molecular mechanisms of RNA polymerase II transcription elongation elucidated by kinetic network models. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 49, 54–62 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang B., Opron K., Burton Z. F., Cukier R. I., and Feig M. (2015) Five checkpoints maintaining the fidelity of transcription by RNA polymerases in structural and energetic details. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1133–1146 10.1093/nar/gku1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang B., Feig M., Cukier R. I., and Burton Z. F. (2013) Computational simulation strategies for analysis of multisubunit RNA polymerases. Chem. Rev. 113, 8546–8566 10.1021/cr400046x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang D., Bushnell D. A., Westover K. D., Kaplan C. D., and Kornberg R. D. (2006) Structural basis of transcription: Role of the trigger loop in substrate specificity and catalysis. Cell 127, 941–954 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maier J. A., Martinez C., Kasavajhala K., Wickstrom L., Hauser K. E., and Simmerling C. (2015) ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3696–3713 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zgarbová M., Šponer J., Otyepka M., Cheatham T. E. 3rd, Galindo-Murillo R., and Jurečka P. (2015) Refinement of the sugar–phosphate backbone torsion beta for AMBER force fields improves the description of Z- and B-DNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 5723–5736 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abraham M. J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J. C., Hess B., and Lindahl E. (2015) GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bayly C. I., Cieplak P., Cornell W. D., and Kollman P. A. (1993) A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: The RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 10269–10280 10.1021/j100142a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H., Izmaylov A. F., et al. (2009) Gaussian 09, Revision B.01. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT 6492 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Darden T., York D., and Pedersen L. (1993) Particle mesh Ewald: An N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 10.1063/1.464397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bussi G., Donadio D., and Parrinello M. (2007) Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 10.1063/1.2408420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berendsen H. J. C., Postma J. P. M., van Gunsteren W. F., DiNola A., and Haak J. R. (1984) Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 10.1063/1.448118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGibbon R. T., Beauchamp K. A., Harrigan M. P., Klein C., Swails J. M., Hernández C. X., Schwantes C. R., Wang L.-P., Lane T. J., and Pande V. S. (2015) MDTraj: A modern open library for the analysis of molecular dynamics trajectories. Biophys. J. 109, 1528–1532 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schrödinger L. L. C. (2015) PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.8. Schrödinger, New York, New York [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu J., Lahiri I., Wang W., Wier A., Cianfrocco M. A., Chong J., Hare A. A., Dervan P. B., DiMaio F., Leschziner A. E., and Wang D. (2017) Structural basis for the initiation of eukaryotic transcription-coupled DNA repair. Nature 551, 653–657 10.1038/nature24658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang W., Walmacq C., Chong J., Kashlev M., and Wang D. (2018) Structural basis of transcriptional stalling and bypass of abasic DNA lesion by RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E2538–E2545 10.1073/pnas.1722050115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Walmacq C., Cheung A. C. M., Kireeva M. L., Lubkowska L., Ye C., Gotte D., Strathern J. N., Carell T., Cramer P., and Kashlev M. (2012) Mechanism of translesion transcription by RNA polymerase II and its role in cellular resistance to DNA damage. Mol. Cell 46, 18–29 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.