Abstract

Epstein–Barr virus–associated gastric cancer (EBVaGC) accounts for about 10% of all gastric cancer cases and has unique pathological and molecular characteristics. EBV encodes a large number of microRNAs, which actively participate in the development of EBV-related tumors. Here, we report that EBV-miR-BART3-3p (BART3-3p) promotes gastric cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, BART3-3p inhibits the senescence of gastric cancer cells induced by an oncogene (RASG12V) or chemotherapy (irinotecan). LMP1 and EBNA3C encoded by EBV have also been reported to have antisenescence effects; however, in EBVaGC specimens, LMP1 expression is very low, and EBNA3C is not expressed. BART3-3p inhibits senescence of gastric cancer cells in a nude mouse model and inhibits the infiltration of natural killer cells and macrophages in tumor by altering the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Mechanistically, BART3-3p directly targeted the tumor suppressor gene TP53 and caused down-regulation of p53's downstream target, p21. Analysis from clinical EBVaGC samples also showed a negative correlation between BART3-3p and TP53 expression. It is well known that mutant oncogene RASG12V or chemotherapeutic drugs can induce senescence, and here we show that both RASG12V and a chemotherapy drug also can induce BART3-3p expression in EBV-positive gastric cancer cells, forming a feedback loop that keeps the EBVaGC senescence at a low level. Our results suggest that, although TP53 is seldom mutated in EBVaGC, its expression is finely regulated such that EBV-encoded BART3-3p may play an important role by inhibiting the senescence of gastric cancer cells.

Keywords: DNA viruses, microRNA (miRNA), cellular senescence, gastric cancer, p53, Epstein-Barr virus, miR-BART3–3p

Introduction

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)3 is a dsDNA virus belonging to the Herpesviridae family, which is etiologically linked to lymphoid and epithelial malignancies, such as Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and gastric carcinoma (GC). EBV infection occurs in 2–20% of GC, with a worldwide average of 10% (1–3). EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBERs) were present in almost all of these tumor cells but not in normal epithelial and stromal cells (4). Elevation of anti-IgG and anti-IgA against viral capsid antigen was found several months before the diagnosis of EBVaGC (5). These findings strongly suggest that EBV plays an important etiological role in the formation and/or development of EBVaGC. Evidence provided by comprehensive molecular analyses proved that EBVaGC is a distinct subset of GC in terms of both its molecular and clinicopathological features (6). Genetic changes that are characteristic of EBVaGC include frequent mutations in PIK3CA and ARID1A and global CpG island hypermethylation of the promoter region of many cancer-related genes. As the most frequently mutated gene in solid tumors, TP53 mutations occur in about 50% of GC but are very rare in EBVaGC (6). Another noteworthy feature of EBVaGC is hyperactivation of the PI3K–AKT signaling (6). EBVaGC belongs to latency infection type I or II in which only EBER, EBNA1, and LMP2A are expressed, but a large number of EBV BART microRNAs are highly expressed (7, 8).

p53 is the most important tumor suppressor activated by DNA damage and other stresses (9, 10). Activation of the p53 pathway leads to temporary or permanent cell cycle arrest, i.e. cell senescence (11). Cell senescence is initiated as a response to cell damage, but its role in tumorigenesis and development is context-dependent (12–14). Notably, senescent cells express a vast number of secreted proteins. This phenotype is termed as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (15). Some malignant transformed cells undergo senescence due to oncogene activation or loss of tumor suppressor (oncogene-induced senescence (OIS)). This phenotype can be vital in the response to some anticancer treatments and is termed therapy-induced senescence (TIS). Activation of the p53/p21CIP1 and/or p16INK4A tumor suppressor pathway is essential for both OIS and TIS. Partial loss of PTEN leads to moderate activation of the PI3K–AKT pathways, which interrupt OIS (16).

The tumorigenesis role of EBV latent infection in host cells is accomplished by manipulating a series of host genes, such as genes related to cellular stress responses, senescence, proliferation, etc. The fine regulation of host genes is considered of great importance for EBV pathogenesis. LMP1, as the most well-known latent protein of EBV, suppresses the expression of p16INK4a, commonly believed to be a key regulator of replicative senescence. LMP1 also prevents RAS-induced premature senescence (17, 18). In vitro, EBV infection of B cells induces a continuous proliferation of B cells, resulting in immortal lymphoblastoid cell lines. It has been reported that EBNA3C acts as a host DNA damage response inhibitor to prevent B cell proliferation from stagnation and promote its immortalization (19). LMP1 is present in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, but only a few EBVaGC specimens expressed LMP1. This raises the question of whether EBV affects the senescence process through other molecules in EBVaGC.

EBV was the first virus to be found to encode microRNAs. It encodes ∼25 microRNA precursors and 44 mature microRNAs, which are divided into two major clusters, BART and BHRF-1 (20). The BHRF-1 cluster is expressed only in lytically infected cells or cells with latency type III infections (21). EBVaGC specimens express a large number of miR-BARTs, whereas almost all EBV oncoproteins are seldom expressed (8). The genes targeted by EBV miR-BARTs are associated with oncogenesis, apoptosis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and signal transductions, but many of them are also involved in tumor progression or have an impact on tumor immune response (22–25). We speculate that TP53, although not mutated, is also closely regulated in EBVaGC, and EBV-encoded miR-BARTs may contribute to p53 modulation and further affect the senescence of GC cells.

In the present study, we show that EBV-miR-BART3-3p (BART3-3p), as a relatively highly expressed microRNA in EBVaGC, can promote the proliferation and inhibit the senescence of GC cells by directly targeting the CDS region of TP53 and inhibiting PTEN. By fine-tuning the two key molecules in the senescence pathway, BART3-3p promotes the development of EBVaGC.

Results

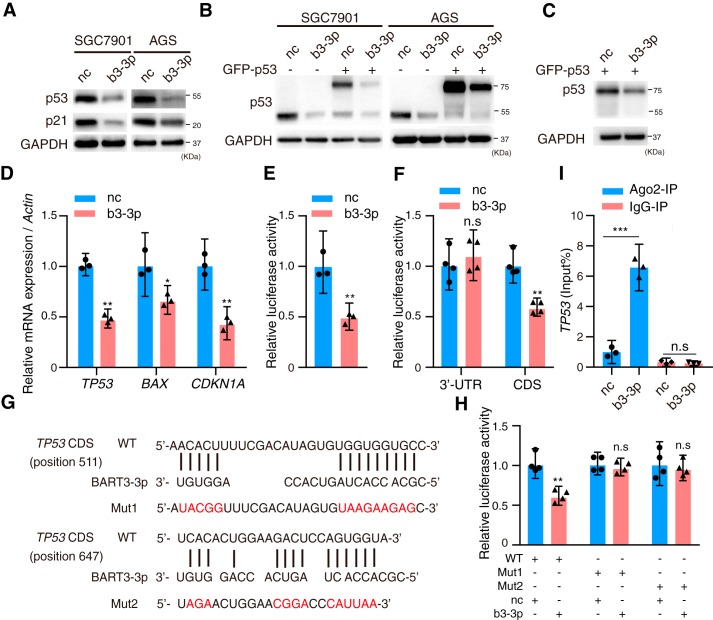

EBV-miR-BART3-3p targets tumor suppressor TP53 in GC

To find the EBV BART microRNAs that may regulate p53, we searched all the BART microRNA seed sequences and found that EBV BART3-3p has several binding sites that can interact with TP53. To investigate whether BART3-3p was one of the possible mechanisms for p53 inactivation or down-regulation in EBVaGC, BART3-3p mimics were transfected into two EBV-negative gastric cancer cell lines, SGC7901 and AGS. p53 and its downstream target, p21, were significantly suppressed at the protein level by BART3-3p mimics (Fig. 1A). Considering that the binding sites of BART3-3p and TP53 mRNA predicted by bioinformatics were located in the TP53 CDS region, we cotransfected BART3-3p mimics and TP53 expression vector GFP-p53, which lacked the TP53 3′-UTR and 5′-UTR, into SGC7901 and AGS cells and found that GFP-p53 was also inhibited (Fig. 1B). We also cotransfected GFP-p53 and BART3-3p mimics into the TP53-deficient cell line KATOIII, and the results further confirmed that exogenous GFP-p53 was suppressed by BART3-3p (Fig. 1C). BART3-3p mimics also significantly decreased the mRNA levels of TP53 and its target genes, CDKN1A and BAX (Fig. 1D). Further study showed that BART3-3p reduced the p53 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1E). To clarify whether TP53 is a direct cellular target gene for BART3-3p, luciferase reporter assays were performed by cotransfection of BART3-3p mimics with the full length of TP53 3′-UTR or CDS-containing luciferase reporter vector into HEK293 cells, respectively. The CDS but not the 3′-UTR luciferase activity was significantly reduced by BART3-3p mimics (Fig. 1F), suggesting that the CDS region of TP53 mRNA may contain the target sites directly targeted by BART3-3p. An online tool for microRNA target prediction, RNAhybrid, showed that two possible binding sites exist in the CDS of TP53 mRNA (from nucleotide positions 511 and 647, respectively) by the seed sequence of BART3-3p (Fig. 1G). The luciferase activity of the WT TP53 CDS but not the mutant CDS was significantly reduced by BART3-3p but not by negative control mimics (Fig. 1H). These results strongly suggest that BART3-3p directly binds to the TP53 CDS region and inhibits its transcription. microRNAs bind to their target genes and carry them to an RNA-induced silencing complex in which Argonaute 2 (Ago2) functions as a platform. SGC7901 cells were transfected with BART3-3p mimics, and then RNA immunoprecipitation was performed by anti-Ago2 antibody. BART3-3p mimics significantly increased the level of TP53 mRNA that binds to Ago2 compared with negative control (nc) mimics (Fig. 1I). Taken together, BART3-3p targets TP53 through binding its CDS region.

Figure 1.

EBV BART3-3p inhibits p53 expression by targeting its CDS region. A, Western blot analysis of p53 and p21 protein expression in SGC7901 and AGS cells transfected with nc mimics or EBV BART3-3p mimics (b3-3p) for 48 h. B, SGC7901 and AGS cells were cotransfected with GFP-p53 and mimics (b3-3p or nc) for 48 h, and exogenous and endogenous p53 was analyzed by Western blotting. C, KATOIII cells were cotransfected with GFP-p53 and mimics (b3-3p or nc) for 48 h. The Western blot shows p53. D, gene expression levels of TP53, BAX, and CDKN1A in SGC7901 cells transfected with mimics (b3-3p or nc) for 48 h were examined by RT-qPCR (n = 3). Expression levels were normalized to nc. E, BART3-3p regulates p53 transcriptional activity. SGC7901 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of p53-responsive reporter pp53-TA-Luc plasmid, 50 ng of Renilla plasmid, and 20 pmol of mimics (b3-3p or nc) (n = 3). Luciferase activity was measured 48 h later, and the data are shown as the relative firefly luciferase activity normalized to the value of Renilla luciferase. F, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with luciferase reporters carrying TP53 3′-UTR (or CDS) and mimics (b3-3p or nc) (n = 4). 48 h later, luciferase activity was measured. The data are shown as the relative firefly luciferase activity normalized to the value of Renilla luciferase. G, BART3-3p and its putative binding sequences in the CDS region of TP53. Mutants of the CDS of TP53 gene were generated in the complementary sites that bind to the seed regions of BART3-3p. H, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with luciferase reporters carrying either the predicted miRNA target site in TP53 CDS (WT) or its corresponding mutants (Mut1 and Mut2) and mimics (b3-3p or nc). Luciferase activity was measured 48 h later. The data are shown as the relative firefly luciferase activity normalized to the value of Renilla luciferase. I, SGC7901 cells were transfected with mimics (b3-3p or nc) for 48 h, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) using either anti-Ago2 antibody or a negative control IgG. The mRNA levels of TP53 binding to Ago2 were detected by RT-qPCR (n = 4). n represents biologically independent samples, and data are shown as the mean ± 95% CI limit. Statistical significance relative to control was assessed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, compared with the control group (nc). n.s., not significant. Error bars represent 95% CI. GAPDH was used for protein loading control. Actin was used for normalizing the expression of mRNAs.

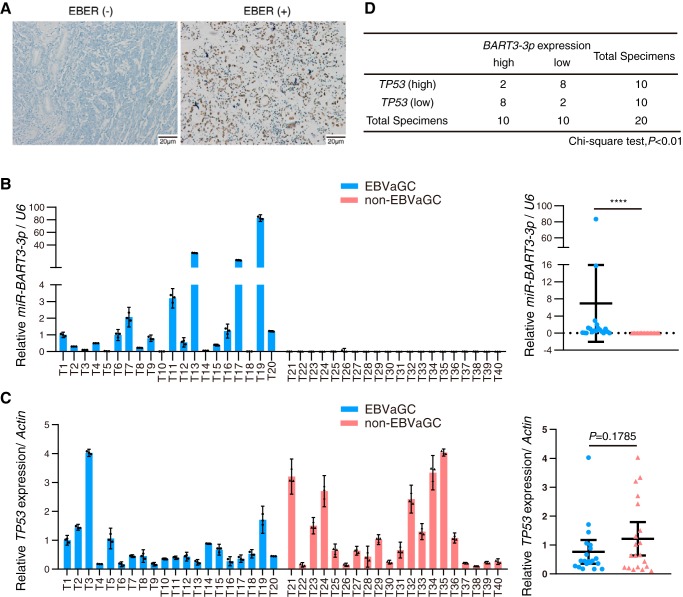

The expression of EBV-miR-BART3-3p and TP53 was correlated in EBVaGC specimens

We collected 20 cases of EBVaGC and 20 cases of non-EBVaGC tissue samples for analyzing the expression levels of TP53 and BART3-3p. The clinic pathological parameters of GC specimens are listed in Table S3. The diagnostic standard of EBVaGC was in situ hybridization positive EBER staining (Fig. 2A). BART3-3p can only be detected in the EBVaGC specimens (although its expression levels varied in the specimens) but not in the non-EBVaGC specimens (Fig. 2B). The average TP53 expression levels are lower in EBVaGC specimens compared with that of non-EBVaGC specimens, but the difference did not reach the significance threshold (p = 0.1785; Fig. 2C). We used the χ2 test to analyze the correlation between the expression levels of BART3-3p and TP53 in EBVaGC specimens. We divided the 20 cases of EBVaGC into two groups, BART3-3p high and BART3-3p low, as well as into TP53 high and TP53 low groups (see “Experimental procedures” for details). The χ2 test showed that BART3-3p in EBVaGC was negatively correlated with TP53 (p < 0.01; Fig. 2D). The above clinical specimen data suggest a possibility that BART3-3p is involved in the regulation of TP53 expression in EBVaGC.

Figure 2.

Expression of BART3-3p is negatively correlated with TP53 in EBVaGC specimens. A, representative images of EBER expression in GC specimens using ISH. Left, negative EBER staining; right, positive staining. B and C, expression levels of BART3-3p (B) and TP53 (C) in 20 cases of EBVaGC (T1–T20) and 20 cases of non-EBVaGC (T21–T40) specimens were detected by stem-loop RT-qPCR (for noncoding RNAs) or RT-qPCR (for genes). The expression values of case T1 are set as 1 (left panel). The right panel shows the individual values of each sample of BART3-3p or TP53 in two groups. Data are shown as the mean ± 95% CI limit. Statistical significance between two groups was assessed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. ****, p < 0.0001. D, correlation analysis of the expression levels of BART3-3p and TP53 in EBVaGC specimens. The median expression values of BART3-3p and TP53 in 20 EBVaGC samples were calculated as a criterion for differentiating “high” and “low” groups. The differences of TP53 expression between BART3-3p (high) and BART3-3p (low) groups were analyzed by χ2 test. Error bars represent 95% CI.

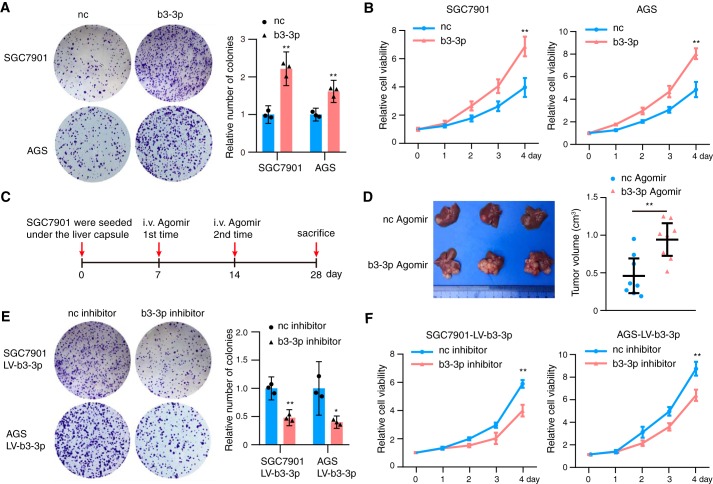

EBV-miR-BART3-3p promotes GC growth in vitro and in vivo

We next investigated the function of BART3-3p in the context of tumor biology in GC cells. BART3-3p mimics were transfected into SGC7901 and AGS cell lines. Colony formation (Fig. 3A) and CCK8 assays (Fig. 3B) demonstrated that expression of BART3-3p can increase the proliferation ability of GC cells compared with the negative control. To study whether BART3-3p promotes gastric cancer growth in vivo, we established a xenograft mouse model. SGC7901 cells were transfected with b3-3p agomir or nc agomir for 12 h and then transplanted into the liver capsule of nude mice. b3-3p agomir or nc agomir was injected into corresponding groups of nude mice through their tail veins on days 7 and 14. All mice were sacrificed on day 28 (Fig. 3C). Both groups had one to several transplanted tumors in the livers, and the average tumor volumes of the b3-3p agomir group was larger than that of the nc group (Fig. 3D). To verify the results, we expressed BART3-3p in SGC7901 and AGS cells by lentivirus-mediated transduction and named the cells as SGC7901 LV-b3-3p and AGS LV-b3-3p (Fig. S1A). Compared with their respective controls, p53 of these two cell lines was decreased (Fig. S1B). BART3-3p inhibitor increased the expression of p53 and its downstream target, p21 protein, in both of the cell lines (Fig. S1C). Consistent with the above results, BART3-3p inhibitor can reverse the cell proliferation induced by BART3-3p in SGC7901 LV-b3-3p and AGS LV-b3-3p cell lines (Fig. 3E). The CCK8 assay also showed the same function of BART3-3p inhibitor in cell proliferation in SGC7901 LV-b3-3p and AGS LV-b3-3p cells (Fig. 3F). These results suggest that BART3-3p promotes the proliferation of GC cells both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 3.

BART3-3p promotes tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. A, a total of 1000 gastric cancer cells transfected with b3-3p mimics (or nc mimics) were seeded in 6-well plates. Colony formation assays were performed, and representative images are shown on the left, and quantification is shown on the right (n = 3). B, proliferation of gastric cancer cells transfected with b3-3p mimics (or nc mimics) was analyzed with the CCK8 assay (n = 3). C, schematic representation of the nude mouse SGC7901 xenograft tumor experimental protocol. D, representative tumor photos of SGC7901 xenografts treated with b3-3p agomir or nc agomir in nude mice. Tumor volume was measured after sacrifice (n = 8, each group). E, SGC7901 LV-b3-3p cells and AGS LV-b3-3p cells were transfected with either nc or BART3-3p inhibitors for 6 h, and then 1000 cells were reseeded. Colony formation assays were performed, and representative images are shown on the left, and quantification is shown on the right (n = 3). F, proliferation of SGC7901 LV-b3-3p cells and AGS LV-b3-3p cells transfected with nc or b3-3p inhibitor was analyzed with the CCK8 assay. n represents biologically independent samples, and data are shown as the mean ± 95% CI limit. Statistical significance relative to control was assessed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. Error bars represent 95% CI.

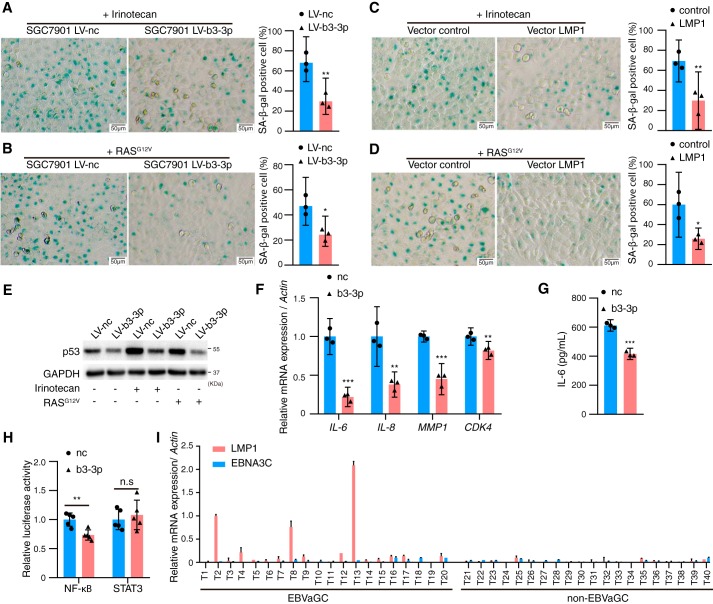

EBV-miR-BART3-3p inhibits cell senescence in vitro

p53 and PTEN are the two master regulators in the senescence pathway. In addition to directly targeting TP53, we also observed that PTEN was inhibited by BART3-3p both at the protein and mRNA levels but not through a direct targeting relationship (Fig. S2). We proposed that BART3-3p may take part in the regulation of cell senescence. To evaluate this hypothesis, we used irinotecan (a chemotherapeutic drug) and RASG12V plasmid to induce either TIS (26) or OIS (27) in SGC7901 LV-b3-3p/SGC7901 LV-nc cells. Both irinotecan and RASG12V significantly induced senescence in SGC7901 LV-nc cells, but their effects were compromised in the SGC7901 LV-b3-3p cells as assessed by senescence-associated β-gal (SA-β-gal) activity (Fig. 4, A and B). EBV-encoded oncoprotein LMP1 has been reported to inhibit senescence (18), so we transfected LMP1 into SGC7901 cell line and found that LMP1's effect on senescence is similar to that of BART3-3p (Fig. 4, C and D). Irinotecan or RASG12V up-regulated p53 protein levels, whereas BART3-3p reversed this effect (Fig. 4E). We next examined the SASP cytokines by qRT-PCR. Cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8) as well as MMP1 and CDK4 were repressed by BART3-3p (Fig. 4F). The IL-6 protein secreted by GC cells is also inhibited by BART3-3p (Fig. 4G). Luciferase reporter assay determined that BART3-3p can inhibit the transcription activity of NF-κB but not that of STAT3, and NF-κB is the master transcriptional factor that promotes the secretory activity of senescent cells (Fig. 4H). BART3-3p can inhibit the RASG12V-induced senescence in the human embryonic lung fibroblast cell line MRC-5 (Fig. S3). In addition to LMP1, EBV-encoded EBNA3C also can inhibit B-cell senescence (19). However, EBNA3C is not expressed in EBVaGC, and LMP1 expression has been negative in most EBVaGC specimens (7, 28). The Cancer Genome Atlas data from 295 GC specimens further confirm this result (6). Here, we also determined the expression levels of LMP1 and EBNA3C in 20 cases of EBVaGC and 20 cases of non-EBVaGC tissue samples and found that only three cases of EBVaGC had LMP1 expression, whereas in the remaining samples we were unable to detect LMP1 and EBNA3C expression (Fig. 4I). These results imply the importance of BART3-3p in senescence in EBVaGC because there is very limited expression of LMP1 and EBNA3C in these cancers.

Figure 4.

BART3-3p inhibits cellular senescence in vitro. A and B, SGC7901 LV-b3-3p or SGC7901 LV-nc cells were treated with irinotecan (A) for 48 h or transfected with 2 μg of RASG12V plasmid (B) for 48 h and stained for SA-β-gal (n = 3). C, SGC7901 cells were transfected with 2 μg of LMP1 plasmid for 24 h, then treated with irinotecan for another 48 h, and stained for SA-β-gal (n = 3). D, SGC7901 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of LMP1 (or negative control) plasmid and 1 μg of RASG12V plasmid for 48 h and stained for SA-β-gal. Representative images are shown on the left, and quantification is shown on the right (n = 3). E, Western blot analysis of p53 protein expression in SGC7901 LV-b3-3p or SGC7901 LV-nc cells treated with irinotecan or transfected with RASG12V plasmid for 48 h. F, mRNA levels of the indicated genes in SGC7901 cells transfected with nc or BART3-3p mimics (n = 3). Actin was used for normalizing the expression of mRNA. G, protein levels of IL-6 in the cell culture supernatants of SGC7901 cells transfected with mimics (nc or BART3-3p) were analyzed by ELISA (n = 3). H, luciferase reporter plasmid PGL3-NF-κB or plasmid STAT3-LUC was cotransfected with mimics (nc or b3-3p) (n = 5) in SGC7901 cells for 24 h. The data are shown as the relative firefly luciferase activity normalized to the value of Renilla luciferase. I, expression levels of LMP1 and EBNA3C in GC specimens were detected by RT-qPCR. The expression values of case T2 LMP1 are set as 1. n represents biologically independent samples, and data are shown as the mean ± 95% CI limit. Statistical significance relative to control was assessed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent 95% CI.

EBV-miR-BART3-3p inhibits cell senescence in vivo

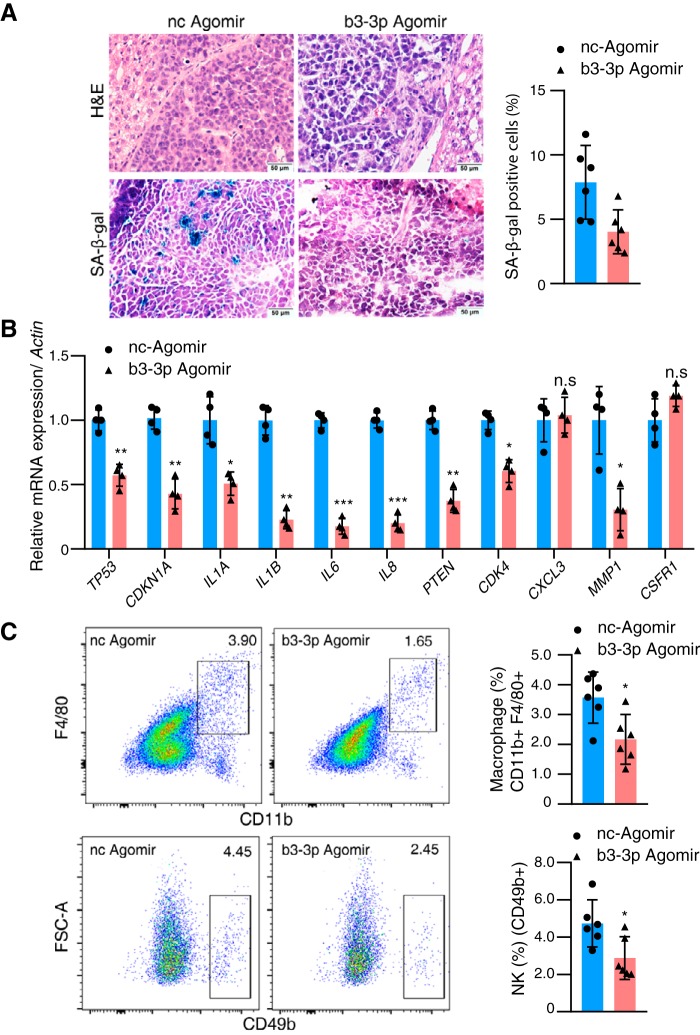

The in vitro study showed a consistent effect of BART3-3p on cell senescence. We then examined the in vivo effect of this discovery by xenografting SGC7901 cells into nude mice (under their liver capsule). Mice were randomly divided into two groups; one was treated with b3-3p agomir, and the other was treated with nc agomir. All mice were sacrificed at 4 weeks, and the tumors were stripped from the liver. SA-β-gal staining showed that the number of senescent cells in the b3-3p agomir group was less than that in the nc agomir group (Fig. 5A). The expression levels of TP53, CDKN1A, CDK4, and SASP cytokines (IL-1A, IL-1B, IL-6, and IL-8) were decreased in the b3-3p agomir group compared with the nc group (Fig. 5B). The number of NK cells and macrophages that infiltrated the tumor tissues of the b3-3p agomir group was reduced compared with the nc group as assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 5C), but the number of macrophages that infiltrated the livers was not different between the two groups (Fig. S4). These results suggest that BART3-3p can inhibit senescence in vivo and possibly reduce the recruitment of immune cells by down-regulating important SASP molecules, thus inhibiting the antitumor immune response.

Figure 5.

BART3-3p inhibits cellular senescence in vivo. A, SA-β-gal staining of the tumor tissues from the xenograft tumor mouse models (see Fig. 3C for nude mouse experimental procedure). Representative images are shown on the left, and quantification is shown on the right (n = 6). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. B, mRNA levels of the indicated genes in the xenograft tumor tissues (n = 4), assayed by RT-qPCR. C, frequencies of macrophages and NK cells in xenograft tumor tissues were determined by flow cytometry (n = 6). Cells were gated on CD11b+F4/80+ and CD49b+ populations, respectively. Representative flow cytometric figures are shown. n represents biologically independent samples. The data are shown as the mean ± 95% CI limit. Statistical significance relative to control was assessed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, compared with the control group. n.s., not significant. Error bars represent 95% CI.

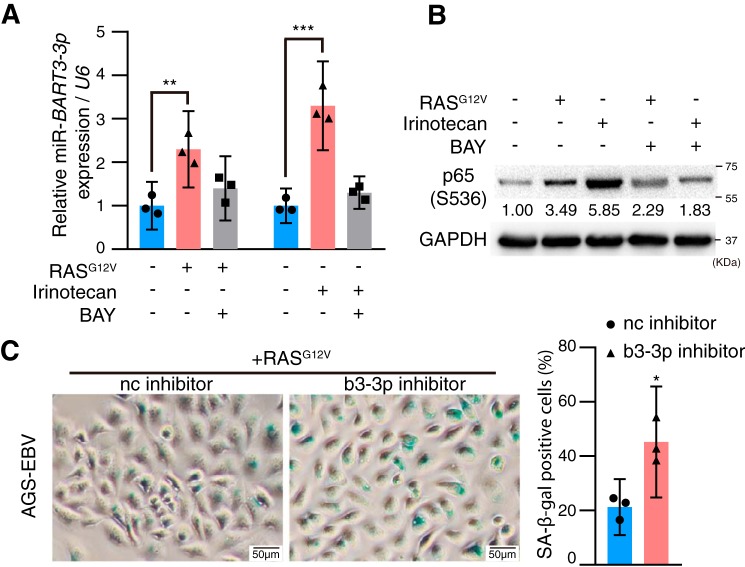

RASG12V and chemotherapy induce BART3-3p expression in EBV-positive GC cells, which constitutes a feedback loop to keep cell senescence at a low level

It has been reported that activation of NF-κB can increase the expression of a variety of EBV microRNAs (29). Because RASG12V and chemotherapy can activate the NF-κB pathway (26), we questioned whether RASG12V and chemotherapy can induce BART3-3p expression in EBV-positive GC cells and found that either irinotecan or RASG12V can significantly increase BART3-3p expression, but addition of the NF-κB inhibitor BAY 11-7028 reversed the increase of BART3-3p (Fig. 6A). We noticed that both RASG12V and irinotecan can activate NF-κB signaling, and the activation was compromised by the addition of BAY 11-7028 (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that RASG12V and chemotherapy can increase the expression of BART3-3p, most likely by activating NF-κB signaling. In the AGS-EBV cells, when b3-3p inhibitors were introduced, the RASG12V-induced senescence was significantly enhanced (Fig. 6C). This result suggests that although RASG12V can induce cancer cell senescence it also can induce BART3-3p expression, and BART3-3p can inhibit senescence; therefore, the cell senescence is kept at a low level in the EBVaGC cells, which normally have WT TP53.

Figure 6.

RASG12V and chemotherapy can induce BART3-3p expression in EBV-positive GC cells, which constitutes a feedback loop to keep cell senescence at a low level. AGS-EBV cells were treated with irinotecan (2.5 μg/ml) alone or together with BAY 11-7028 (2.5 μm) for 12 h or transfected with RASG12V alone for 24 h or with addition of BAY 11-7028 (2.5 μm) after 12 h of transfection for another 12 h. Then BART3-3p expression was detected by qRT-PCR. U6 was used for normalizing the expression of BART3-3p. A, BART3-3p expression levels were calculated from three independent experiments, and data are shown as the mean ± 95% CI limit. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. B, expression levels of phospho-p65 (Ser-536) were detected by Western blotting. C, AGS-EBV cells were transfected with 2 μg of RASG12V plasmid and b3-3p inhibitor (or nc inhibitor) for 48 h and stained for SA-β-gal (n = 3; n represents biologically independent samples). Representative images are shown on the left, and quantification is shown on the right. *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent 95% CI.

Discussion

EBVaGC has recently attracted a lot of attention. This type of gastric cancer has unique biological characteristics, such as hypermethylation and rarely exhibiting TP53 mutation. The role of EBV and its encoded RNAs in the tumorigenesis and progression of EBVaGC still needs intensive study. EBV is a very low-profile virus with very few molecules expressed during latent infection, but BART microRNAs are the exceptions, with high abundance during latent infection. The high expression of low-immunogenicity microRNAs and limited expression of high-immunogenicity viral proteins resulting from long-term evolution will benefit virus survival from the host cells' antivirus immune response. More attention should be paid to the function and clinical significance of the EBV microRNAs. In this study, we report that BART3-3p is a potent inhibitor of senescence. This is the first time that EBV has been reported to inhibit GC cell senescence through miR-BARTs.

EBV BART3-3p promoted GC cell proliferation and inhibited senescence through targeting TP53 and therefore played a key role in promoting tumor progression in EBVaGC. Senescence is a state of permanent cell cycle arrest when cells confront different damaging stimuli. Due to the activation of an irreversible proliferation arrest, cellular senescence is seen as a strong safeguard against tumorigenesis (30). Loss of p53 activity or loss of p16INK4A, a frequent strategy used by tumor cells, leads to elimination of the senescence response (31). Partial loss of PTEN leads to moderate activation of the PI3K–AKT pathway, which disrupts OIS (16). Multiple microRNAs have been reported to play a regulatory role in cell senescence. For example, miR-30 inhibits both p16INK4A and p53, two key senescence effectors, leading to efficient senescence disruption (32). miR-137 targets KDM4A mRNA during RAS-induced senescence and activates both the p53 and Rb pathways (33). miRNA-34a induces esophageal squamous cancer cell senescence-like changes via down-regulation of SIRT1 and up-regulation of p53/p21 (34). In this study, p53 and its downstream target, p21, were negatively regulated by BART3-3p, but p16 did not appear to be affected (results not shown).

Senescent cells are not dormant cells but are metabolically active (35). They express a large number of secreted proteins, which is known as SASP (15). SASPs are observed in tumor cell senescence, which involves a large number of inflammatory cytokines (most notably IL-1a, IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-8) and chemokines and provides a strong link between senescence and antitumor immunity. Here, we found that several SASP molecules were significantly reduced by BART3-3p both in vivo and in vitro (Figs. 4F and 5B). It is noteworthy that SASP differs in different tissues and in different stimuli, but inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-8, are highly conserved parts of SASP and play a major role in maintaining SASP responses in the senescent cell itself and in the affected tissues. Given that NF-κB and STAT3 are the major driver of the SASP, we tested whether BART3-3p affects them. We found that BART3-3p inhibited the luciferase reporter activity of NF-κB but not STAT3, suggesting that the effect of BART3-3p on SASP was achieved by restraining NF-κB activity (Fig. 4F). SASP modulates the infiltration of immune cells in tumor tissues, and we found that the number of NK and macrophages in the tumor microenvironment is decreased in the BART3-3p agomir group compared with the nc group, whereas the number of macrophages in liver tissues was not different between the two groups (Fig. 5C and Fig. S4). This result suggests that the reduction of immune infiltrating cells may be one of the reasons for the greater tumor size in the BART3-3p agomir group. Recent studies seem to have different perspectives on the relationship between SASP and tumorigenesis. Milanovic et al. (36) reported that postsenescent cells with “hijacked” SASP exerted their detrimental potential at relapse by driving a much more aggressive growth phenotype using p53-regulatable models of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia. Menendez and Alarcón (37) suggested that, in a neoplastic background, cell senescence seems to be a beneficial response to tumor progression by controlling tumor growth.

Some studies have addressed the relationship between EBV and cell senescence. EBV infection in vitro drives primary human B cells into indefinitely proliferating lymphoblastoid cells. This process of growth transformation depends on a subset of viral latent oncoproteins and noncoding RNAs. The viral latent oncoprotein EBNA3C was required to attenuate the EBV-induced DNA damage response to prevent proliferation arrest (19). EBV oncoprotein LMP1 can inhibit RAS-mediated induction of p16INK4a and p21WAF to promote senescence bypass; LMP1 also prevents RAS-induced senescence in IMR90 and REF52 fibroblasts (18). However, EBNA3C is not expressed and LMP1 is seldom expressed in EBVaGC specimens. There is very limited expression of LMP1 and almost no expression of EBNA3C in the 20 EBVaGC specimens (Fig. 4I), which suggests that these EBV-encoded oncoproteins are unlikely to play an antisenescence role in EBVaGC. Here, we report that EBV-encoded BART3-3p regulates the cellular senescence pathway in gastric cancer. BART3-3p plays a negative role in the regulation of p53/p21 in EBVaGC and inhibits the expression of PTEN protein, thus preventing GC cell senescence and promoting EBVaGC progression. We speculate that strict control of cell senescence is essential for the survival of EBV, whether in newly infected cells or in EBV-associated tumors. As a relatively highly expressed noncoding RNA in EBVaGC, BART3-3p's regulation of senescence has important significance for both virus survival and the GC process.

We recently reported another BART microRNA, BART5-3p, that can directly target TP53 by combining with TP53 3′-UTR, thereby promoting the progression of EBV-positive epithelial tumors (38). Unlike BART5-3p, BART3-3p binds to the TP53 CDS region but not 3′-UTR (Fig. 1F). Much that is known about how miRNAs regulate gene expression comes from studies of miRNA-binding sites located in the 3′-UTR of mRNA. The work of Hausser et al. (39) demonstrated that target sites located in the CDS are most potent in inhibiting translation, whereas sites located in the 3′-UTR are more efficient in triggering mRNA degradation. Both BART3-3p and BART5-3p have similar effects on cell biological behavior, but BART3-3p has a more obvious senescence-inhibition phenotype of gastric cancer cells. This may be because BART3-3p not only directly targets p53/p21 but also represses the PTEN pathway. Li and co-workers (23, 24) revealed that both BART7-3p and BART1 can inhibit PTEN signaling. Thus, one conclusion that can be made is that the master tumor suppressors are under attack by EBV microRNAs.

There are a few target genes reported to be regulated by BART3-3p. Lei et al. (40) reported that BART3-3p overcame the growth-suppressive activity of DICE1 and stimulated cell proliferation. Kang et al. (41) identified CASZ1a as a target gene of BART3-3p and accordingly demonstrated that it is one of the EBV microRNAs with an antiapoptosis effect. According to the authors, BART3-3p can be combined with the 3′-UTR regions of both DICE1 and CASZ1a. Because BART3-3p targets several important tumor suppressor genes, it has oncogene characteristics in the development of EBV-associated epithelial tumors. Our study revealed a novel function of BART3-3p for inhibition of oncogene- or chemotherapy-induced senescence through suppression of p53 and PTEN, which has significance to keep the senescence at a low level in EBVaGC.

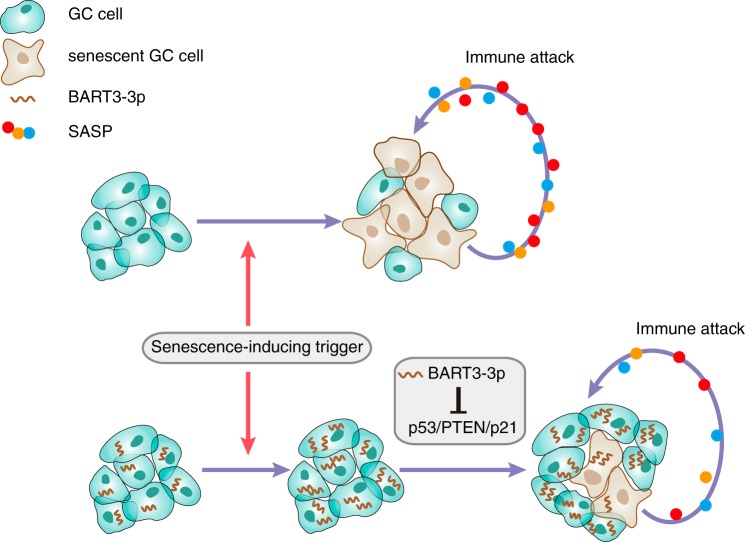

It has been reported that BARTs are up-regulated by NF-κB, and LMP1 induces BART miRNA expression through NF-κB signaling (29). Here, we report that both OIS and TIS can up-regulate the expression of BART3-3p, which constitutes a negative feedback mechanism to keep the senescence of GC cells at a low level. When EBV-positive GC cells undergo OIS or TIS, they can activate NF-κB signaling, thus up-regulating the expression of BART3-3p. Increased BART3-3p can negatively regulate the senescence by targeting p53/p21 signaling and partly inhibiting PTEN (Fig. 7). According to a series of reported BART target genes, BART molecules may represent an important strategy for EBV to regulate host cell proliferation, death, senescence, and the anti-infection immune response during latent infection (42–46). EBV-encoded microRNAs should be given attention because they do not directly produce viral proteins and thus do not form traditional viral antigens to be recognized by the host immune system.

Figure 7.

A proposed model demonstrating the role of BART3-3p in EBVaGC. Senescence-inducing triggers, such as mutant oncogenes (RASG12V) or chemotherapeutic drugs, can induce GC cell senescence. Meanwhile, the senescent GC cells secrete SASP factors that can recruit immune cells to inhibit GC progression. In EBVaGC, the same triggers also induce BART3-3p expression, and BART3-3p can inhibit senescence through inhibiting p53/p21/PTEN. Consequently, cell senescence is kept at a low level in the EBVaGC cells, which normally have WT TP53. Lower levels of SASP secretion imply lower levels of immune attack. Altogether, BART3-3p promotes tumor progression in EBVaGC through inhibiting the senescence pathway.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and reagents

SGC7901 (EBV-negative GC cell line) and KATOIII (GC cell line) cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. AGS (EBV-negative GC cell line) cells were maintained in Ham's F-12 medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. AGS-EBV (EBV-positive GC cell line) (47, 48) also received 400 μg of G418/ml. HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. microRNA mimics and inhibitors were purchased from GenePharma Inc. (Shanghai, China; the sequence information is listed in Table S1). EBV-miR-BART3-3p and negative control agomirs were purchased from Ribobio (Guangzhou, China). The cells were transfected with RNAs and/or plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen).

Clinical gastric cancer specimens

EBVaGC was defined as EBER-positive using in situ hybridization (ISH) as described later in the text. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) surgical specimens, including adequate cases of EBVaGC and non-EBVaGC, were obtained from the Xiangya Hospital (Hunan, China), selected by the senior pathologist. 20 EBVaGC and 20 non-EBVaGC specimens were collected for the analysis of BART3-3p, TP53, LMP1, and EBNA3C expression. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Collections and use of tissue samples were approved by the ethical review committees of the Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

TaqMan microRNA assay

Total RNAs from surgical specimens were extracted using the RecoverAll total nucleic acid isolation kit for FFPE according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). The miRNA (mature BART3-3p or U6)-specific RT primers and miRNA-specific TaqMan probes were purchased from Thermo (Waltham, MA), and miRNA expression was detected by TaqMan microRNA assays according to the manufacturer's protocol. The results were normalized to U6.

Lentivirus transduction

Lentivirus packaging was made by GenePharma Inc. A lentiviral vector plasmid, LV3 (H1/GFP&Puro), was used in this study to construct the stable cell lines. The randomized flanking sequence control (mock) and EBV-miR-BART3-3p were purchased from GenePharma Inc. and transduced into cells following the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

Protein extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with antibodies against p53 (DO-1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:500), p21 (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:500), phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) (93H1) (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1000), and GAPDH (Sangon Biotech; 1:5000). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was used as the secondary antibody. The antigen–antibody reaction was visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence assay.

Tumor xenograft procedures in nude mice

All nude mice (4–5 weeks old; male) were purchased from the Central Animal Facility of Central South University. To assess tumor growth and infiltration of immune cells, 16 nude mice received a 0.5-cm cut on their abdominal sections, and their livers were pushed partially out of their abdominal cavities. Then 50 μl of SGC7901 cells (1 × 106) transfected with b3-3p agomir or nc agomir (2 nmol) for 24 h with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, catalog number 354234) were injected into their liver capsules. Finally, their livers were carefully pushed back into their abdominal cavities after pressing the pinhole with alcohol cotton balls for 2 min. After 7 days, the 16 mice were randomly divided into two groups. One group was injected with 10 nmol of BART3-3p (b3-3p) agomir into the tail vein, and the other group was injected with 10 nmol of nc agomir. A repeat injection of 10 nmol of BART3-3p agomir or nc agomir was given on the 14th day in the corresponding group. All mice were sacrificed at 4 weeks. The tumors were stripped from the livers, and the tumor volumes were measured and calculated using the following formula: (A × B2)/2 where A is the largest diameter and B is the perpendicular diameter. A part of each tumor tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and transferred to a gradient of ethanol. Tumors were embedded in paraffin, sectioned with Leica RM2245, and processed for histological examinations. Frozen sections were also prepared directly from tumor tissues. All surgeries were performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Central South University.

Cell preparation and FACS analysis

Resected xenograft tumors were washed in PBS. Tumor tissues were cut into small pieces by scissors in RPMI 1640 medium, collagenase D, and DNase I; incubated for 6 min at 37 °C; and then passed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon). The resulting cells were purified using Percoll (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation. For analysis of macrophages and NK cells, the cells were stained with F4/80-APC (clone RM8), anti-CD49b-PE (clone DX5), and anti-CD11b-APC/Cy7 (clone M1/70), which were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Samples were analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Olten, Switzerland).

Plasmids and Dual-Luciferase reporter assay

The full lengths of the TP53 3′-UTR or CDS were amplified and subcloned into the pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase miRNA target expression vector. TP53 CDS mutant plasmids were synthesized and constructed by GeneCreate Biotech (Wuhan, China). The pp53-TA-luc luciferase reporter plasmid was purchased from Beyotime (Jiangsu, China) to monitor the transcriptional activity of p53. For miRNA target gene verification, HEK293 cells were seeded in 48-well plates and cotransfected with 200 ng of the luciferase reporter plasmid (TP53 3′-UTR, CDS, WT, or mutant) along with 20 pmol of BART3-3p or nc mimics. For p53 transcriptional activity detection, SGC7901 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of pp53-TA-luc luciferase reporter plasmid and 40 ng of Renilla plasmid along with 20 pmol of BART3-3p or nc mimics. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured via a Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). The data were expressed as the relative firefly luciferase activity normalized to the value of Renilla luciferase.

Analysis of mRNA levels

Total RNAs were extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). For mRNA reverse transcription, 2 μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using a RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For miRNA reverse transcription, 1 μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using a Mir-X miRNA first-strand synthesis kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The levels of gene transcripts were detected by qRT-PCR using specific primers and a SYBR Premix Ex TaqII kit (Takara). The expression levels of miRNA and mRNA were quantified by measuring cycle threshold (Ct) values and normalized to U6 and actin, respectively. The data were further normalized to the negative control, unless otherwise indicated. The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S2.

ELISA

ELISA was performed as described previously (49). An ELISA kit for IL-6 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Colony formation assay

Cells with different treatments were planted into 6-well plates (1000 cells/well) and incubated for 12 days. Plates were washed with PBS and stained with crystal violet. The number of colonies with more than 50 cells was counted.

SA-β-gal staining of histological sections and cultured cells

For xenograft tissues samples, SA-β-gal staining was performed in frozen sections using a Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining kit (Beyotime, catalog number C0602). Briefly, 12-μm tissue frozen sections were fixed at room temperature for 15 min with fixation solution, washed three times with PBS, and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C with the staining solution containing X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside). Sections were then counterstained with eosin. Cells were stained for SA-β-gal activity according to the instruction manual. Briefly, SGC7901 and MRC5 cells were fixed with fixation solution for 15 min at room temperature. Fixed cells then were washed with PBS and stained at 37 °C for 24 h.

In situ hybridization

EBER ISH was performed on the FFPE tissue sample slides using an EBER1 probe ISH kit (Zsbio, Beijing, China). Only those with a universal and unequivocal nuclear staining within almost all tumor cells were interpreted as EBV-positive.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was determined by independent t test or analysis of variance using SPSS17.0 and GraphPad Prism 5. Significance parameters were set at p values < 0.05.

Author contributions

J. W., G. L., and J. M. conceptualization; J. W. data curation; J. W. formal analysis; J. W. validation; J. W., X. Z., Z. L., Y. F., P. L., G. L., J. L., and J. M. investigation; J. W., X. Z., Z. Q., L. W., Y. L., Q. P., Xuemei Zhang, Xiaoyue Zhang, C. L., and J. M. methodology; J. W., J. L., and J. M. writing-original draft; J. W. and J. M. project administration; Z. Q., L. W., Y. L., Q. P., Y. G., Q. Y., J. L., and J. M. resources; W. X. and J. M. funding acquisition; J. M. supervision.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Ya Cao and Lun-Qun Sun for providing reagents.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81472694, 81672889, 81672993, and 31670171; China 111 Project Grant 111-2-12; Hunan Province Science and Technology Project Grant 2016JC2035; and Key Laboratory of Translational Radiation Oncology Hunan Province Open Research Fund Program Grant 2015TP1009. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S1–S3.

- EBV

- Epstein–Barr virus

- EBVaGC

- Epstein–Barr virus–associated gastric cancer

- miR

- microRNA

- NK

- natural killer

- SASP

- senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- GC

- gastric carcinoma

- EBER

- EBV-encoded small RNA

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- OIS

- oncogene-induced senescence

- TIS

- therapy-induced senescence

- CDS

- coding sequence

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog

- nc

- negative control

- Ago2

- Argonaute 2

- SA-β-gal

- senescence-associated β-gal

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- IL

- interleukin

- miRNA

- microRNA

- ISH

- in situ hybridization

- FFPE

- formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- APC

- allophycocyanin

- PE

- phycoerythrin

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- CI

- confidence interval.

References

- 1. Chen J. N., He D., Tang F., and Shao C. K. (2012) Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma: a newly defined entity. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 46, 262–271 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318249c4b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee J. H., Kim S. H., Han S. H., An J. S., Lee E. S., and Kim Y. S. (2009) Clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24, 354–365 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05775.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murphy G., Pfeiffer R., Camargo M. C., and Rabkin C. S. (2009) Meta-analysis shows that prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric cancer differs based on sex and anatomic location. Gastroenterology 137, 824–833 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Speck O., Tang W., Morgan D. R., Kuan P. F., Meyers M. O., Dominguez R. L., Martinez E., and Gulley M. L. (2015) Three molecular subtypes of gastric adenocarcinoma have distinct histochemical features reflecting Epstein-Barr virus infection status and neuroendocrine differentiation. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 23, 633–645 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levine P. H., Stemmermann G., Lennette E. T., Hildesheim A., Shibata D., and Nomura A. (1995) Elevated antibody titers to Epstein-Barr virus prior to the diagnosis of Epstein-Barr-virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 60, 642–644 10.1002/ijc.2910600513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2014) Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 513, 202–209 10.1038/nature13480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luo B., Wang Y., Wang X. F., Liang H., Yan L. P., Huang B. H., and Zhao P. (2005) Expression of Epstein-Barr virus genes in EBV-associated gastric carcinomas. World J. Gastroenterol. 11, 629–633 10.3748/wjg.v11.i5.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shinozaki-Ushiku A., Kunita A., Isogai M., Hibiya T., Ushiku T., Takada K., and Fukayama M. (2015) Profiling of virus-encoded microRNAs in Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma and their roles in gastric carcinogenesis. J. Virol. 89, 5581–5591 10.1128/JVI.03639-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sherr C. J. (2004) Principles of tumor suppression. Cell 116, 235–246 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01075-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vogelstein B., Lane D., and Levine A. J. (2000) Surfing the p53 network. Nature 408, 307–310 10.1038/35042675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oren M. (2003) Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 10, 431–442 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan J. M., Ho S. H., and Tai I. T. (2010) Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine-induced cellular senescence in colorectal cancers in response to irinotecan is mediated by P53. Carcinogenesis 31, 812–819 10.1093/carcin/bgq034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eggert T., Wolter K., Ji J., Ma C., Yevsa T., Klotz S., Medina-Echeverz J., Longerich T., Forgues M., Reisinger F., Heikenwalder M., Wang X. W., Zender L., and Greten T. F. (2016) Distinct functions of senescence-associated immune responses in liver tumor surveillance and tumor progression. Cancer Cell 30, 533–547 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saab R. (2011) Senescence and pre-malignancy: how do tumors progress? Semin. Cancer Biol. 21, 385–391 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coppé J. P., Patil C. K., Rodier F., Sun Y., Munoz D. P., Goldstein J., Nelson P. S., Desprez P. Y., and Campisi J. (2008) Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 6, 2853–2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vredeveld L. C., Possik P. A., Smit M. A., Meissl K., Michaloglou C., Horlings H. M., Ajouaou A., Kortman P. C., Dankort D., McMahon M., Mooi W. J., and Peeper D. S. (2012) Abrogation of BRAFV600E-induced senescence by PI3K pathway activation contributes to melanomagenesis. Genes Dev. 26, 1055–1069 10.1101/gad.187252.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xin B., He Z., Yang X., Chan C. P., Ng M. H., and Cao L. (2001) TRADD domain of Epstein-Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 is essential for inducing immortalization and suppressing senescence of primary rodent fibroblasts. J. Virol. 75, 3010–3015 10.1128/JVI.75.6.3010-3015.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang X., He Z., Xin B., and Cao L. (2000) LMP1 of Epstein-Barr virus suppresses cellular senescence associated with the inhibition of p16INK4a expression. Oncogene 19, 2002–2013 10.1038/sj.onc.1203515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nikitin P. A., Yan C. M., Forte E., Bocedi A., Tourigny J. P., White R. E., Allday M. J., Patel A., Dave S. S., Kim W., Hu K., Guo J., Tainter D., Rusyn E., and Luftig M. A. (2010) An ATM/Chk2-mediated DNA damage-responsive signaling pathway suppresses Epstein-Barr virus transformation of primary human B cells. Cell Host Microbe 8, 510–522 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pfeffer S., Zavolan M., Grässer F. A., Chien M., Russo J. J., Ju J., John B., Enright A. J., Marks D., Sander C., and Tuschl T. (2004) Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science 304, 734–736 10.1126/science.1096781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Imig J., Motsch N., Zhu J. Y., Barth S., Okoniewski M., Reineke T., Tinguely M., Faggioni A., Trivedi P., Meister G., Renner C., and Grässer F. A. (2011) microRNA profiling in Epstein-Barr virus-associated B-cell lymphoma. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 1880–1893 10.1093/nar/gkq1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Albanese M., Tagawa T., Bouvet M., Maliqi L., Lutter D., Hoser J., Hastreiter M., Hayes M., Sugden B., Martin L., Moosmann A., and Hammerschmidt W. (2016) Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs reduce immune surveillance by virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6467–E6475 10.1073/pnas.1605884113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cai L., Ye Y., Jiang Q., Chen Y., Lyu X., Li J., Wang S., Liu T., Cai H., Yao K., Li J. L., and Li X. (2015) Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA BART1 induces tumour metastasis by regulating PTEN-dependent pathways in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 6, 7353 10.1038/ncomms8353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cai L. M., Lyu X. M., Luo W. R., Cui X. F., Ye Y. F., Yuan C. C., Peng Q. X., Wu D. H., Liu T. F., Wang E., Marincola F. M., Yao K. T., Fang W. Y., Cai H. B., and Li X. (2015) EBV-miR-BART7-3p promotes the EMT and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by suppressing the tumor suppressor PTEN. Oncogene 34, 2156–2166 10.1038/onc.2014.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. He B., Li W., Wu Y., Wei F., Gong Z., Bo H., Wang Y., Li X., Xiang B., Guo C., Liao Q., Chen P., Zu X., Zhou M., Ma J., et al. (2016) Epstein-Barr virus-encoded miR-BART6-3p inhibits cancer cell metastasis and invasion by targeting long non-coding RNA LOC553103. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2353 10.1038/cddis.2016.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chien Y., Scuoppo C., Wang X., Fang X., Balgley B., Bolden J. E., Premsrirut P., Luo W., Chicas A., Lee C. S., Kogan S. C., and Lowe S. W. (2011) Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev. 25, 2125–2136 10.1101/gad.17276711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Serrano M., Lin A. W., McCurrach M. E., Beach D., and Lowe S. W. (1997) Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 88, 593–602 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81902-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nishikawa J., Imai S., Oda T., Kojima T., Okita K., and Takada K. (1999) Epstein-Barr virus promotes epithelial cell growth in the absence of EBNA2 and LMP1 expression. J. Virol. 73, 1286–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Verhoeven R. J., Tong S., Zhang G., Zong J., Chen Y., Jin D. Y., Chen M. R., Pan J., and Chen H. (2016) NF-κB signaling regulates expression of Epstein-Barr virus BART microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Virol. 90, 6475–6488 10.1128/JVI.00613-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sharpless N. E., and Sherr C. J. (2015) Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 397–408 10.1038/nrc3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ito Y., Hoare M., and Narita M. (2017) Spatial and temporal control of senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 820–832 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee E., Collazo-Lorduy A., Castillo-Martin M., Gong Y., Wang L., Oh W. K., Galsky M. D., Cordon-Cardo C., and Zhu J. (2018) Identification of microR-106b as a prognostic biomarker of p53-like bladder cancers by ActMiR. Oncogene 37, 5858–5872 10.1038/s41388-018-0367-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neault M., Mallette F. A., and Richard S. (2016) miR-137 modulates a tumor suppressor network-inducing senescence in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Rep. 14, 1966–1978 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ye Z., Fang J., Dai S., Wang Y., Fu Z., Feng W., Wei Q., and Huang P. (2016) MicroRNA-34a induces a senescence-like change via the down-regulation of SIRT1 and up-regulation of p53 protein in human esophageal squamous cancer cells with a wild-type p53 gene background. Cancer Lett. 370, 216–221 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoshimoto S., Loo T. M., Atarashi K., Kanda H., Sato S., Oyadomari S., Iwakura Y., Oshima K., Morita H., Hattori M., Hattori M., Honda K., Ishikawa Y., Hara E., and Ohtani N. (2013) Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 499, 97–101 10.1038/nature12347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Milanovic M., Fan D. N. Y., Belenki D., Däbritz J. H. M., Zhao Z., Yu Y., Dörr J. R., Dimitrova L., Lenze D., Monteiro Barbosa I. A., Mendoza-Parra M. A., Kanashova T., Metzner M., Pardon K., Reimann M., et al. (2018) Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature 553, 96–100 10.1038/nature25167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Menendez J. A., and Alarcón T. (2017) Senescence-inflammatory regulation of reparative cellular reprogramming in aging and cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 5, 49 10.3389/fcell.2017.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zheng X., Wang J., Wei L., Peng Q., Gao Y., Fu Y., Lu Y., Qin Z., Zhang X., Lu J., Ou C., Li Z., Zhang X., Liu P., Xiong W., et al. (2018) Epstein-Barr virus microRNA miR-BART5-3p inhibits p53 expression. J. Virol. 92, e01022–18 10.1128/JVI.01022-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hausser J., Syed A. P., Bilen B., and Zavolan M. (2013) Analysis of CDS-located miRNA target sites suggests that they can effectively inhibit translation. Genome Res. 23, 604–615 10.1101/gr.139758.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lei T., Yuen K. S., Xu R., Tsao S. W., Chen H., Li M., Kok K. H., and Jin D. Y. (2013) Targeting of DICE1 tumor suppressor by Epstein-Barr virus-encoded miR-BART3* microRNA in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 133, 79–87 10.1002/ijc.28007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kang D., Skalsky R. L., and Cullen B. R. (2015) EBV BART microRNAs target multiple pro-apoptotic cellular genes to promote epithelial cell survival. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004979 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jiang C., Chen J., Xie S., Zhang L., Xiang Y., Lung M., Kam N. W., Kwong D. L., Cao S., and Guan X. Y. (2018) Evaluation of circulating EBV microRNA BART2-5p in facilitating early detection and screening of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 143, 3209–3217 10.1002/ijc.31642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jung Y. J., Choi H., Kim H., and Lee S. K. (2014) MicroRNA miR-BART20-5p stabilizes Epstein-Barr virus latency by directly targeting BZLF1 and BRLF1. J. Virol. 88, 9027–9037 10.1128/JVI.00721-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lu Y., Qin Z., Wang J., Zheng X., Lu J., Zhang X., Wei L., Peng Q., Zheng Y., Ou C., Ye Q., Xiong W., Li G., Fu Y., Yan Q., and Ma J. (2017) Epstein-Barr virus miR-BART6-3p inhibits the RIG-I pathway. J. Innate Immun. 9, 574–586 10.1159/000479749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Qiu J., and Thorley-Lawson D. A. (2014) EBV microRNA BART 18-5p targets MAP3K2 to facilitate persistence in vivo by inhibiting viral replication in B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 11157–11162 10.1073/pnas.1406136111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fan C., Tang Y., Wang J., Xiong F., Guo C., Wang Y., Xiang B., Zhou M., Li X., Wu X., Li Y., Li X., Li G., Xiong W., and Zeng Z. (2018) The emerging role of Epstein-Barr virus encoded microRNAs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Cancer 9, 2852–2864 10.7150/jca.25460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Borza C. M., and Hutt-Fletcher L. M. (2002) Alternate replication in B cells and epithelial cells switches tropism of Epstein-Barr virus. Nat. Med. 8, 594–599 10.1038/nm0602-594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marquitz A. R., Mathur A., Shair K. H., and Raab-Traub N. (2012) Infection of Epstein-Barr virus in a gastric carcinoma cell line induces anchorage independence and global changes in gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 9593–9598 10.1073/pnas.1202910109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang X., Wei L., Wang J., Qin Z., Wang J., Lu Y., Zheng X., Peng Q., Ye Q., Ai F., Liu P., Wang S., Li G., Shen S., and Ma J. (2017) Suppression colitis and colitis-associated colon cancer by anti-S100a9 antibody in mice. Front. Immunol. 8, 1774 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.