Abstract

Sphingolipids compose a lipid family critical for membrane structure as well as intra- and intercellular signaling. De novo sphingolipid biosynthesis is initiated by the enzyme serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), which resides in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. In both yeast and mammalian species, SPT activity is homeostatically regulated through small ER membrane proteins, the Orms in yeast and the ORMDLs in mammalian cells. These proteins form stable complexes with SPT. In yeast, the homeostatic regulation of SPT relies, at least in part, on phosphorylation of the Orms. However, this does not appear to be the case for the mammalian ORMDLs. Here, we accomplished a cell-free reconstitution of the sphingolipid regulation of the ORMDL–SPT complex to probe the underlying regulatory mechanism. Sphingolipid and ORMDL-dependent regulation of SPT was demonstrated in isolated membranes, essentially free of cytosol. This suggests that this regulation does not require soluble cytosolic proteins or small molecules such as ATP. We found that this system is particularly responsive to the pro-apoptotic sphingolipid ceramide and that this response is strictly stereospecific, indicating that ceramide regulates the ORMDL–SPT complex via a specific binding interaction. Yeast membranes harboring the Orm–SPT system also directly responded to sphingolipid, suggesting that yeast cells have, in addition to Orm phosphorylation, an additional Orm-dependent SPT regulatory mechanism. Our results indicate that ORMDL/Orm-mediated regulation of SPT involves a direct interaction of sphingolipid with the membrane-bound components of the SPT-regulatory apparatus.

Keywords: sphingolipid, homeostasis, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lipid metabolism, lipid signaling, cell signaling, phytoceramide, sphingomyelin, sphingosine

Introduction

Sphingolipids have wide-ranging biological functions both as structural elements of biological membranes and as potent and specific signaling molecules (reviewed in Refs. 1–5). This is a diverse family of lipids that includes sphingosines, ceramides, sphingomyelin, and glycosphingolipids. All sphingolipids are derived by modification of the long-chain base (LCB)2 sphingoid backbone. The initiating and rate-limiting step for production of this backbone is accomplished by serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) through the condensation of an amino acid, usually serine, and a fatty acyl-CoA, usually palmitoyl-CoA. As expected for an initiating and rate-limiting metabolic enzyme, SPT is homeostatically controlled in both yeast and higher eukaryotes (6–8); elevated cellular sphingolipid results in reduced SPT activity. SPT is a multisubunit membrane protein consisting of two major subunits (LCBl and LCB2 in yeast, SPTLC1 and SPTLC2 or SPTLC3 in mammals) complexed to a variety of smaller subunits that alter both the activity and specificity of the enzyme (reviewed in Refs. 9 and 10). SPT resides in the endoplasmic reticulum. Insight into the mechanism underlying homeostatic control of SPT has been advanced by the discovery of small membrane-bound proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum, the Orms in yeast and ORMDLs in mammals, which are required for this regulation (6, 8, 11, 12). In the absence of the Orms/ORMDLs SPT is not inhibited by elevated cellular sphingolipid levels. There are three isoforms of ORMDLs in mammalian cells and two Orm isoforms in yeast (6, 11–13). The Orms and ORMDLs form stable complexes with SPT (6, 12, 14). This association depends on the first transmembrane segment of LCB1/SPTLC1 (15). Although there has been progress in understanding how the Orms are regulated in yeast, there is little known about how the mammalian ORMDL system detects sphingolipid levels and regulates SPT. In yeast Orms are phosphorylated at N-terminal serine residues by the Ypk1 kinase, downstream of TORC2, in response to reduced cellular sphingolipid levels (6, 12, 16). This releases SPT from Orm inhibition, thus allowing replenishment of sphingolipids. However, the mammalian ORMDLs, although otherwise homologous to the yeast proteins, lack the N-terminal peptide region that is phosphorylated in yeast (reviewed in Ref. 17). This suggests that the mammalian ORMDL–SPT complex utilizes a distinct mechanism to both sense cellular sphingolipid and to relay that information to the ORMDL–SPT system. Here we utilize a cell-free reconstitution of sphingolipid regulation of the ORMDL–SPT complex to characterize the underlying mechanism.

Results

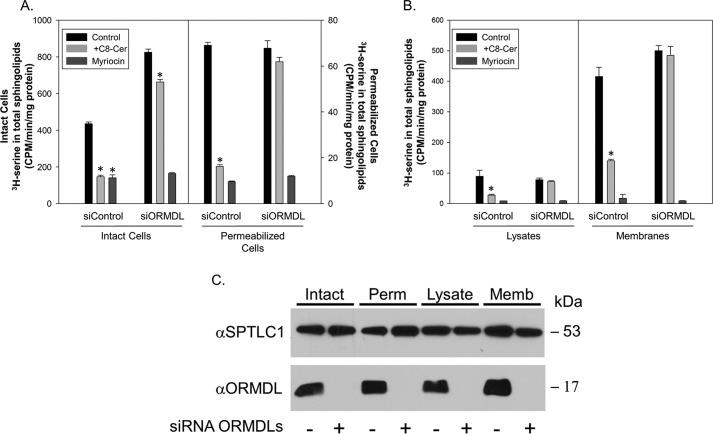

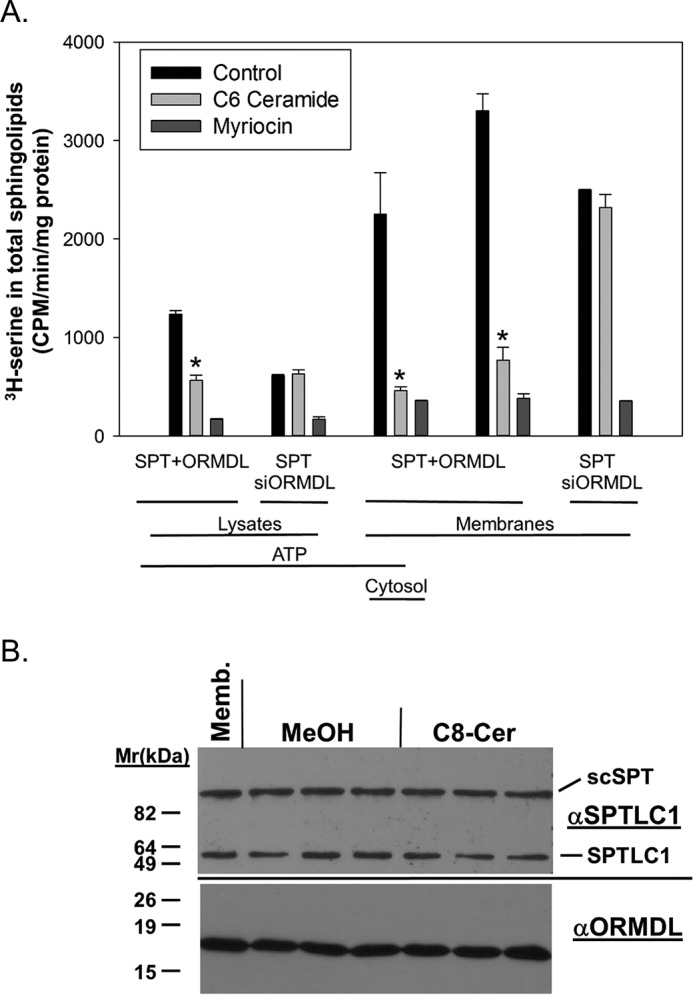

To produce a tool to characterize ORMDL-dependent regulation of SPT by sphingolipid we tested whether this regulation could be reconstituted in a cell-free system. To accomplish this we examined intact and permeabilized cells, cell lysates, and ultimately, membranes, for their ability to respond to sphingolipids in an ORMDL-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Previously we used incorporation of [3H]serine into ceramide as a measure of de novo ceramide biosynthesis to demonstrate that in intact cells ORMDLs are required for the inhibition of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis by soluble short-chain ceramide (8, 14). We have used incubation with ceramides containing short fatty acids (C6 and C8) as native-chain length ceramides (generally from C14–C26) are insoluble. Here we replicated that result, measuring incorporation of [3H]serine into total sphingolipid as a reflection of SPT activity (Fig. 1A, left, Intact Cells). Cells were incubated with vehicle or C8 ceramide for 1 h and then incubated with [3H]serine for an additional hour after which total sphingolipids were extracted and incorporation of [3H]serine into sphingolipids was measured by scintillation counting. Incubation with C8 ceramide strongly inhibited de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis. This inhibition was eliminated if the cells were depleted of all three ORMDL isoforms by siRNA transfection, similar to our previous findings (8), confirming that the ORMDLs are required for homeostatic regulation of SPT. Also similar to our previous study, we found that depletion of the ORMDLs increases basal SPT activity, indicating that the ORMDLs constitutively inhibit SPT. These conditions were repeated with cells in which the plasma membrane was permeabilized by treatment with digitonin (Fig. 1A, right), similar to our previous study (8). As before we found that in permeabilized cells C8 ceramide inhibits SPT activity, but that the response is eliminated in cells depleted of the ORMDLs. It is notable that the absolute incorporation of radioactivity into sphingolipid is reduced in the permeabilized cells. This may be a reflection of serine pool size in the intact cells or may be the result of inactivation of SPT by the permeabilization conditions.

Figure 1.

ORMDL-dependent inhibition of SPT by ceramide can be reconstituted with isolated membranes. A, SPT activity was measured in intact and permeabilized cells as described under “Experimental procedures.” B, lysates and total membranes were prepared and assay of SPT in response to 10 μm C8 ceramide was performed as described under “Experimental procedures” with incubations at 37 °C for 60 min. MeOH/BSA solutions were used as the control. Also shown is inhibition of SPT by 1 μm myriocin. Shown are the mean of nine technical replicates for intact and permeabilized cells and quadruplicate technical replicates for lysates and membranes, mean ± S.D. Shown is one representative of two duplicate experiments. C, samples assayed in A and B were assessed for ORMDL and subunit 1 of SPT (SPTLC1) by immunoblotting in the presence and absence of ORMDL knockdown by siRNA. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.01) between control and C8 ceramide-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test.

To establish whether a more defined biochemical reconstitution of the sphingolipid control of SPT could be accomplished, we generated both total cell lysates and isolated total membranes from control-transfected cells and cells depleted of the ORMDLs by siRNA transfection (Fig. 1B). This transfection was efficient at reducing ORMDL protein levels (Fig. 1C). SPT activity was measured by the incorporation of [3H]serine into total sphingolipids by a well-established technique (18). Lysates or membranes were incubated on ice with vehicle, C8 ceramide, or myriocin (a potent inhibitor of SPT) for 40 min prior to measurement of SPT activity. When measured in total cell lysates, which includes both membranes and cytosol, there is a strong inhibition of SPT activity by preincubation of the lysates with C8 ceramide (Fig. 1B, left). This inhibition is lost with ORMDL depletion. Similarly, isolated total cellular membranes exhibited a robust SPT activity that was markedly inhibited by preincubation with C8 ceramide (Fig. 1B, right). This inhibition was eliminated when the membranes were prepared from cells depleted of all three ORMDL isoforms by siRNA transfection. Considering that the membranes are largely depleted of cytosolic components this result suggests that the ORMDL-dependent inhibition of SPT in response to sphingolipid is independent of soluble cytosolic proteins and small molecules, including ATP. This is a strong indication that this response is not due to post-translational modifications of elements of this regulatory system.

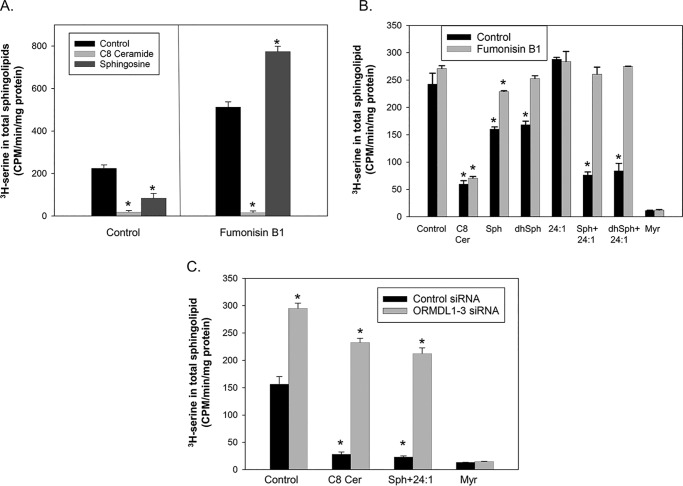

The results depicted in Fig. 1 illustrate that the ORMDL/SPT regulatory system is functional in isolated membranes in response to soluble, short-chain ceramides. The longer, native chain length ceramides cannot be directly added to membranes as they are insoluble. Consequently, to test the ability of native, longer chain ceramides to trigger this response we established a system in which ceramides are generated in these membranes in a cell-free system (Fig. 2). First we repeated earlier results (7, 8) in intact cells demonstrating that incubation of cells with sphingosine results in an ORMDL-dependent inhibition of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis (Fig. 2A, left). However, as also illustrated here, sphingosine must be converted to ceramide to inhibit SPT. The ceramide synthase inhibitor Fumonisin B1 blocks sphingosine-mediated inhibition of SPT (Fig. 2A, right). This establishes that the lipid being monitored by this homeostatic system is ceramide or a downstream metabolite. To test whether the inhibition by native ceramides is reproduced in isolated membranes we generated ceramides by preincubating the membranes with substrates for ceramide synthase, sphingosine, and fatty acyl-CoA, both alone and together, prior to measuring SPT activity (Fig. 2B). Preincubation of membranes with sphingosine alone resulted in a partial inhibition of SPT activity under these conditions. This inhibition is blocked by inclusion of the ceramide synthase inhibitor Fumonisin B1 (Fig. 2, gray bars), indicating that the added sphingosine is utilized to generate ceramides, presumably using endogenous fatty acyl-CoAs in the membranes as the acyl substrate. It is notable that Fumonisin B1 does not block the ability of C8 ceramide to inhibit SPT, establishing that the effect of Fumonisin B1 is specific. As an exogenous fatty acyl-CoA donor we utilized 24:1 CoA as 24:1 ceramide is an abundant ceramide species in HeLa membranes (data not shown) and therefore Cers2, the ceramide synthase that utilizes this substrate (19), appears to be active in HeLa cells. As depicted in Fig. 2B, the inclusion of the fatty acyl donor 24:1 CoA by itself did not yield any SPT inhibition. However, the combination of 24:1 CoA with sphingosine enhanced the inhibition resulting from sphingosine alone and equaled the inhibition resulting from C8 ceramide treatment. That inhibition was completely blocked by inhibiting ceramide synthesis with Fumonisin B1. In the de novo biosynthetic pathway ceramide is generated by introduction of a 4,5-bond in the sphingosine backbone of the saturated species, dihydroceramide, by dihydroceramide desaturase (20, 21). To test whether the saturated species, dihydroceramide, is active in the ORMDL–SPT system we tested the ability of dihydrosphingosine, in the absence and presence of 24:1 CoA, to inhibit SPT activity. As with sphingosine, preincubation of membranes with dihydrosphingosine alone inhibits SPT to a moderate extent and inclusion of 24:1 CoA yields strong inhibition (Fig. 2B, dhSph + 24:1). In both cases inhibition was eliminated by inclusion of Fumonisin B1 to inhibit dihydroceramide synthesis. Considering that the reductants for dihydroceramide desaturase, NADH and NADPH, were absent from these incubations, it is unlikely that there is substantial generation of ceramide in these reactions (21). This indicates that dihydroceramide is also sensed by the ORMDL–SPT homeostatic regulatory system. Myriocin, a specific inhibitor of SPT, was included as a measure of complete SPT inhibition. To confirm that the inhibition of SPT we detect by the cell-free generation of ceramide is ORMDL-dependent we tested the sensitivity of inhibition induced by preincubation with sphingosine and 24:1 CoA to the presence of ORMDL by comparing membranes from control-transfected cells with membranes derived from cells depleted of the ORMDLs by siRNA transfection (Fig. 2C). Depletion of the ORMDLs largely reversed SPT inhibition resulting from preincubation with sphingosine and 24:1 CoA, similar to that seen with C8 ceramide. These experiments establish that the ceramide-sensitive ORMDL–SPT regulatory system is contained entirely within the membranes that house those proteins.

Figure 2.

Ceramides generated either in intact cells or in isolated membranes trigger ORMDL-dependent inhibition of SPT. A, cells preincubated either in the presence or absence of the ceramide synthase inhibitor Fumonisin B1 (FB1) overnight were incubated with or without 10 μm sphingosine or 10 μm C8 ceramide for 2 h then assayed for de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis. Shown are the mean ± S.D. of myriocin-inhibitable counts of six technical replicates. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.001) between control and C8 ceramide or sphingosine-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test. Shown is one of two virtually identical experiments. B, total cell membranes were preincubated with vehicle, 20 μm C8 ceramide, 20 μm sphingosine, 20 μm dihydrosphingosine, 50 μm 24:1 CoA, or sphingosines and 24:1 CoA for 40 min at 37 °C as described under “Experimental procedures.” The membranes were then assayed for SPT activity as described under “Experimental procedures.” Membranes were tested either in the absence or presence of the ceramide synthase inhibitor FB1 (20 μm). Also included was an incubation with 1 μm myriocin, a specific inhibitor of SPT, as a control. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.05) between control and C8 ceramide or (dh)sphingosine and/or 24:1 CoA-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test. C, membranes from cells transfected either with control siRNA or siRNA directed against all three ORMDL isoforms were preincubated with vehicle, 20 μm C8 ceramide, or 20 μm sphingosine and 50 μm 24:1 CoA, for 40 min as described under “Experimental procedures” and then assayed for SPT activity as described under “Experimental procedures.” Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.01) between control and ORMDL-depleted membranes with or without the indicated lipid treatments by Student's two-tailed t test. Shown is one of at least two (for intact cells) or three (for isolated membranes) independent experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. for 4 technical replicates.

We sought to obtain an indication of whether the ORMDL–SPT complex itself was sufficient to detect ceramide levels or whether there might be additional components. Producing a functional purified system containing only these proteins is currently not technically feasible. To gain some insight, however, we produced membranes from cells overexpressing ORMDL3 and SPT. Because SPT is a multisubunit enzyme we used a construct, previously utilized by this and other laboratories (14, 22) that consists of a fusion polypeptide incorporating the two major SPT subunits, SPTLC1 and -2, and a minor subunit, ssSPTa (23). This construct is termed scSPT (for single-chain SPT). Similar to the studies using untransfected cells depicted in Fig. 1B, we tested both lysates and membranes from these cells as well as adding back cytosol to the isolated membranes and testing the effect of added ATP. Both lysates and isolated membranes from cells overexpressing ORMDL3 and scSPT responded to short-chain ceramide by inhibition of SPT activity (Fig. 3A). Transfection with scSPT is labeled “SPT.” This response was independent of added cytosol or ATP, confirming that neither proteins, cytosolic co-factors, nor ATP are required for ORMDL-dependent inhibition of SPT by ceramide. This response was ablated in lysates and membranes derived from cells overexpressing scSPT but depleted of ORMDLs by siRNA transfection. The protein levels of the ORMDLs and SPT were unaffected by short-chain ceramide treatment (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The response of membranes containing overexpressed ORMDL3 and a single-chain fusion of SPT subunits does not require either ATP or cytosol. ORMDL-dependent inhibition of SPT by ceramide in membranes overexpressing a single-chain fusion of SPT subunits and ORMDL3 is independent of ATP and cytosol. A, HeLa cells were transfected with either a control siRNA in combination with a construct expressing scSPT (22) and a plasmid directing overexpression of mouse ORMDL3 (labeled SPT + ORMDL) or siRNAs directed against all three ORMDL isoforms in combination with a plasmid only for scSPT (labeled SPT/siORMDL). After 24 h cells were broken by Dounce homogenization as described under “Experimental procedures.” Either total lysates (11 μg, unfractionated, containing both cytosol and membranes) or cytosol-free membranes (12 μg, isolated by ultracentrifugation) were assayed for SPT activity. Where indicated ATP (1 mm) or cytosol (8 μg) was added. Assays included BSA (control), BSA/C6 ceramide (10 μm), or myriocin (1 μm), a direct inhibitor of SPT. MeOH/BSA solutions were used as the Control. SPT activity was measured as described under “Experimental procedures” by the incorporation of [3H]serine into a total sphingolipid fraction. Incubations were performed for 90 min at 37 °C. Shown are the averages of triplicate samples, mean ± S.D. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.02) between control and C6 ceramide-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test. Shown is one representative of 3 similar experiments. B, acute ceramide-dependent inhibition of SPT does not involve changes in ORMDL levels. Membranes derived from HeLa cells overexpressing human ORMDL3 and scSPT were incubated with either BSA/MeOH or BSA/C8 ceramide (10 μm final concentration) under conditions identical to those required to trigger SPT inhibition (e.g. Fig. 1B). Membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF, and immunoblotting. Blots were cut just below the 47-kDa marker. The upper blot was probed with an antibody to the SPT subunit SPTLC1, which stains both endogenous SPTLC1 and the SPT fusion protein (scSPT). The lower blot was probed with an antibody to ORMDL. Shown are an equivalent amount of the membranes used in the incubation (Memb.) and triplicate incubations with either the BSA/MeOH control (MeOH) or BSA/C8 ceramide (C8-Cer).

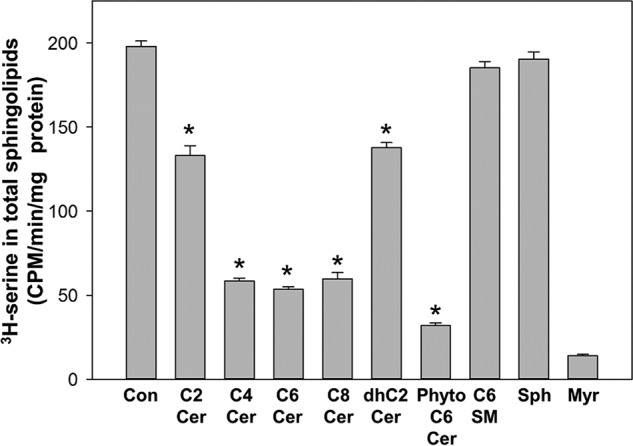

To test the range of lipids to which the ORMDL–SPT complex is responsive we examined the inhibitory properties of dihydroceramide, phytoceramide (the predominant yeast ceramide), sphingomyelin, sphingosine, and ceramides with fatty acyl chains of increasing length (Fig. 4). The potency of the ceramides increases with increasing fatty acyl chain length. This is unsurprising given the considerably longer chain lengths of endogenous ceramides. Dihydroceramide was inhibitory, as expected from the results generating this lipid in membranes as depicted in Fig. 2B. It was somewhat surprising that phytoceramide was a potent inhibitor given that this lipid is a minor sphingolipid in mammalian cells. Sphingomyelin was not inhibitory, suggesting that this system monitors ceramide and not later sphingolipid metabolites. Sphingosine was not inhibitory in this set of experiments, in contrast to sphingosine inhibition found in the experiments depicted in Fig. 2B. In the experiments depicted in Fig. 4, lipids were preincubated on ice prior to assay for SPT activity, so the lipids were essentially unmodified prior to measurement of SPT activity. In contrast, in the experiments depicted in Fig. 2 the membranes were preincubated at 37 °C prior to assaying SPT activity to generate ceramides.

Figure 4.

The ORMDL–SPT complex responds to ceramide and phytoceramide. The response to ceramide is more robust as the length of the N-acyl chain increases. 20 μm of the indicated sphingolipids, added as complexes with BSA, were tested for the ability to trigger inhibition of SPT activity as described under “Experimental procedures.” MeOH/BSA solutions were used as the control. The SPT inhibitor, myriocin (1 μm), was also tested to establish SPT-specific incorporation of [3H]serine into the sphingolipid fraction. Incubations were performed for 60 min at 37 °C. Shown are the averages of triplicate samples, mean ± S.D. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.01) between control and lipid-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test. Shown is one representative of 3 similar experiments. Con, BSA control; C2-C8 Cer, the fatty acid N-acylated to the sphingosine backbone; Phyto C6 Cer, C6 phytoceramide; C6 SM, C6 sphingomyelin; Sph, sphingosine; Myr, myriocin.

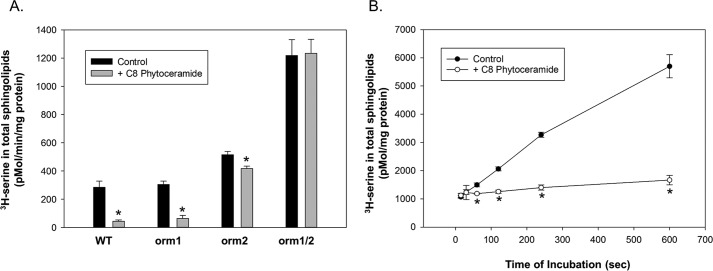

Yeast Orm–SPT complex directly and rapidly responds to phytoceramide in isolated membranes

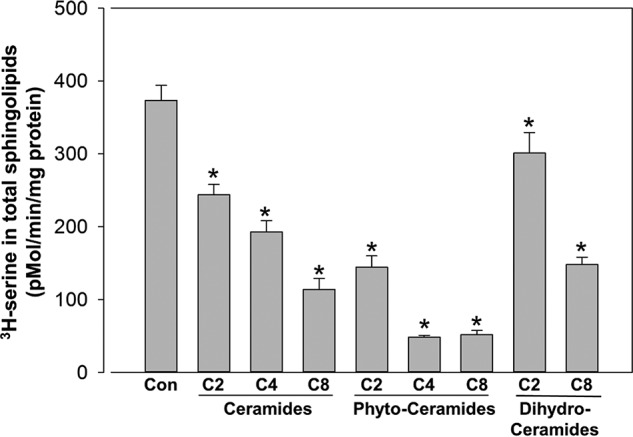

Orm phosphorylation in yeast has been shown to be a primary sphingolipid-responsive SPT regulatory mechanism (6, 16, 24). However, to test whether this was layered over a more direct response of the Orm–SPT complex to sphingolipid we tested whether SPT was regulated by sphingolipid in isolated membranes in the absence of ATP, and therefore not phosphorylation-dependent (Fig. 5A). Membranes were isolated from WT yeast and yeast deficient in Orm1, Orm2, or both and assayed for sphingolipid-dependent inhibition of SPT using C8 phytoceramide. Phytoceramide is the predominant ceramide in yeast and short-chain phytoceramide was a potent inhibitor of SPT activity in membranes from WT cells. This inhibition was significantly reduced in membranes from Orm2-deficient cells. Surprisingly, there was little or no effect of deletion of Orm1 by itself. However, deletion of Orm1 and Orm2 together strongly stimulated basal SPT activity and completely eliminated regulation by added phytoceramide. This establishes that this acute regulation of SPT by phytoceramide is Orm-dependent. The response of SPT to phytoceramide was very rapid, observable within minutes of incubation (Fig. 5B). The lipid specificity of SPT regulation in yeast membranes was tested by measuring SPT activity in response to increasing N-acyl chain lengths of phytoceramide, ceramide, and dihydroceramide (Fig. 6). As expected, phytoceramide was the most potent of these lipids. However, both ceramide and, to a lesser extent, dihydroceramide, could also trigger inhibition of SPT. This suggests that, similar to what we have observed in mammalian cells, the response of the yeast Orm–SPT system to sphingolipids demonstrates specificity with respect to sphingolipid structure.

Figure 5.

SPT in isolated yeast membranes rapidly responds to phytoceramide in an Orm-dependent manner. A, Orm dependence of phytoceramide inhibition of SPT activity in isolated yeast microsomes. Microsomes isolated from WT yeast (WT) and yeast strains with deletions of Orm1 (orm1) Orm2 (orm2) or deleted of both Orm isoforms (orm1/2) were assayed for SPT activity in the absence (Control) or presence of 20 μm C8 phytoceramide (+ C8 phytoceramide) as described under “Experimental procedures.” Nonspecific background, as determined by assays in the absence of palmitoyl-CoA (less than 10% of signal), was subtracted. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.001) between control and C8 phytoceramide-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test. B, phytoceramide inhibition of SPT is rapid. Assays of SPT activity in isolated yeast microsomes was determined at various times as indicated in the absence (Control) or presence of 20 μm C8 phytoceramide (+ C8 phytoceramide) as described under “Experimental procedures.” The sample collected after 15 s, the shortest practical incubation time, is considered the background in this assay. Shown in A are the mean ± S.D. of 3 separate experiments with triplicate technical replicates in each. Shown for B is the mean ± S.D. of single points from 4 independent experiments. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.005) between control and C8 phytoceramide-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test.

Figure 6.

SPT in yeast microsomes is more responsive to phytoceramide than ceramide or dihydroceramide. The indicated lipids were added at 20 μm to yeast microsomes and assayed for SPT activity as described under “Experimental procedures.” Nonspecific background, as determined by assays in the absence of palmitoyl-CoA (less than 10% of signal), was subtracted. Shown are the mean ± S.D. of 3 separate experiments with triplicate technical replicates in each. Asterisks denote significance (p < 0.005) between control and sphingolipid-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test.

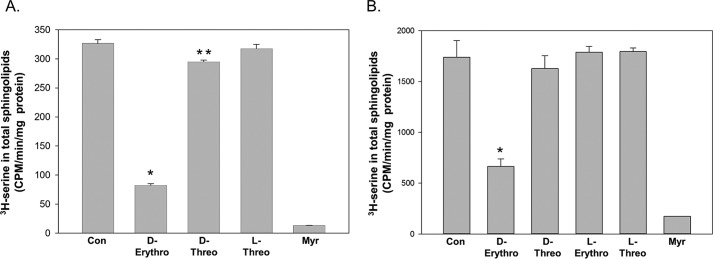

The ORMDL–SPT complex only responds to the native stereoisomer of ceramide

The mechanism by which ceramide is monitored by the ORMDL–SPT system could, in principle, be accomplished by the influence of ceramide on the physical properties of the ER membrane in which these proteins are embedded. Ceramide has well-established effects on the membrane environment (reviewed in Ref. 25). Alternatively, ceramide could bind directly to a component of the regulatory apparatus in a ligand-like manner. To distinguish between these possibilities we tested one of the hallmarks of specific binding: stereospecificity. Ceramide has two chiral centers (at C3 and the C2-nitrogen) and thus there are four potential stereoisomers. Three of these are commercially available in the C8 form and all four are available in the C2 form. We tested the ability of the C8 forms of d-threo and l-threo as well as the native d-erythro form in membranes from untransfected cells (Fig. 7A). Strikingly only d-erythro ceramide induced inhibition of SPT. The C2-based stereoisomers were tested in membranes from cells overexpressing scSPT and ORMDL3 and again only the native stereoisomer, d-erythro, induced SPT inhibition (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The ORMDL–SPT complex in isolated membranes is only responsive to the native stereoisomer of ceramide. The indicated stereoisomers of either (A) C8 ceramide (40 μm, tested in membranes from untransfected cells) or (B) C2 ceramide (20 μm, tested in membranes from cells overexpressing scSPT and hORMDL3), were added as complexes with BSA and tested for the ability to trigger inhibition of SPT as described under “Experimental procedures.” MeOH/BSA solutions were used as the Control. Note that d-erythro ceramide is the natural stereoisomer. The SPT inhibitor myriocin (1 μm) was also tested to establish SPT-specific incorporation of [3H]serine into the sphingolipid fraction. Incubations were performed for 60 min at 37 °C. Shown are the averages of quadruplicate samples, mean ± S.D. For A, single asterisks denote significance (p < 0.001) between control and ceramide-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test, double asterisks denote significance (p < 0.02) between control and ceramide-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test. For B, asterisks denote significance (p < 0.01) between control and ceramide-treated samples by Student's two-tailed t test. Shown is one representative of 3 similar experiments.

Discussion

The Orms/ORMDLs are essential proteins in the homeostatic regulation of sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis through modulating the activity of the rate-limiting enzyme SPT (reviewed in Refs. 10 and 17). The central questions in this system are: what is the molecular mechanism that measures sphingolipid levels in this system? How does the sensed sphingolipid act through ORMDL/Orm to inhibit SPT? What are the sphingolipid(s) that are monitored? In yeast, phosphorylation of the Orms by the TORC2/Ypk1 pathway is a key mechanism (6, 16). However, the mammalian ORMDLs lack homologous phosphorylation sites and are not phosphorylated at other sites (data not shown) and therefore respond by a different mechanism. Here we have accomplished a cell-free reconstitution of this regulatory system to begin to address the underlying sphingolipid sensing mechanism to which the ORMDL–SPT complex responds.

We have demonstrated that in membranes, in the absence of added cytosol or ATP, the ORMDL–SPT complex responds to the addition of soluble ceramides or to the generation of native chain-length ceramides. Although it remains possible that trace amounts of either cytosolic proteins or ATP remaining in the membrane preparation are utilized in this system, a more straightforward explanation is that soluble cellular components are not required for regulation. This limits the potential mechanisms by which regulation of the ORMDL–SPT complex is accomplished. The absence of soluble cytosolic proteins and soluble co-factors indicates that post-translational modifications of either the ORMDLs or SPT are unlikely to be a component of this regulatory system. Consistent with this notion we cannot detect that changes in sphingolipid levels alter SPT or ORMDL protein levels, induce changes in the association of SPT with ORMDL, or affect the molecular weight of either protein (Fig. 3B and Refs. 8 and 14). These observations indicate that sphingolipids induce a conformational change within the ORMDL–SPT complex by either a direct interaction with the ORMDL–SPT complex or with an as yet unidentified component of the regulatory system, and these conformational changes result in reduced SPT activity. The structural nature of the change in SPT that alters activity remains to be determined. SPT activity depends on an interaction between the SPTLC1 and -2 subunits (26) (reviewed in Ref. 10) and the association of the small SPT subunits with the SPTLC1/2 heterodimer has profound effects on SPT activity (27). It therefore seems plausible that ORMDL responds to increased sphingolipid levels by inducing a subtle shift in the relative positions of the SPT subunits within the SPT complex to reduce catalytic activity. It is also possible that changes in conformation of one or both of the core SPT subunits shifts positions of critical residues within the active site (reviewed in Ref. 10).

These studies indicate that the sphingolipid being sensed by this system is ceramide, although it remains possible that other lipids are also active to some degree. In this (Figs. 2 and 4) and a previous study (8) we demonstrated that unmodified sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine are inactive to trigger SPT inhibition. Only when sphingosines are metabolized to ceramide are they inhibitory. Therefore either ceramide or complex sphingolipids, such as sphingomyelin or glycosphingolipids, are sensed in this system. Sphingomyelin was inactive in the cell-free assay of ORMDL–SPT regulation (Fig. 4) suggesting it is not a triggering lipid. Because the soluble sugar nucleotides required for glycosphingolipid synthesis are absent from the reconstitution of this system in isolated membranes, it is unlikely that appreciable levels of glycosphingolipid are produced in these incubations from ceramide either added directly to membranes or generated in the membranes. These data indicate that the primary lipid sensed by this system is ceramide. However, further work will be required to confirm that ceramide itself is the only sphingolipid that is sensed by the ORMDL/Orm–SPT complex.

Critically, we observe a strict stereospecificity in the ability of ceramide to induce ORMDL-dependent inhibition of SPT. Stereospecificity is a hallmark of direct ligand binding. This observation indicates that ceramide directly binds a component of the ORMDL regulatory system rather than exerting its affect by altering the lipid environment of the complex. This regulation is retained when SPT and ORMDL are overexpressed. This indicates that either one of these proteins, or the complex, contains the regulatory binding site for ceramide or that an additional component is present in sufficient amounts in membranes to accommodate the overexpressed proteins. Direct binding studies will be required to resolve these possibilities.

We find that the yeast Orm–SPT system also responds directly to sphingolipid (Figs. 5 and 6), which is somewhat surprising considering the well-established role of Orm phosphorylation in its regulation of SPT (reviewed in Ref. 17). The regulation of the Orms in yeast by the nutrient-sensing TORC pathways (6, 12, 16, 28, 29) is understandable given the requirements of a free-living organism to respond to environmental conditions. The direct regulation we describe here is apparently layered on top of the TORC pathways to accommodate short-term changes in sphingolipid metabolism. The mammalian ORMDL system is also likely regulated at multiple levels to accommodate a range of metabolic and environmental responses. Here we describe an acute and direct modulation of SPT activity mediated by ORMDL, which does not rely on changes in ORMDL protein levels. However, several reports indicate that ORMDL protein levels are regulated for longer term changes in sphingolipid metabolism. Turnover of ORMDL at the protein level has been implicated as a regulator of steady-state ORMDL levels in response to the activity of SPT (30), to inflammatory mediators (31), and to cholesterol loading (32). Regulation of ORMDL gene expression has been described in response to viral infection (33, 34) and by inflammatory and allergic stimuli (35–37). These multiple levels of control of sphingolipid biosynthesis mediated by the ORMDLs is hardly surprising given the biological importance of this class of lipids.

The short-term response of the ORMDL–SPT system to ceramide may be a nimble mechanism that maintains ceramide levels at sufficient concentrations for the production of complex sphingolipids but which prevents the accumulation of ceramide to levels that trigger apoptosis. This control would be especially important during periods of robust synthesis of complex sphingolipids such as in membrane synthesis of growing cells and in specialized tissues that produce high levels of sphingolipid such as skin (reviewed in Ref. 38) and myelinating glia (39). In these cases there is a high level of flux through ceramide to sphingomyelin and glycosphingolipids. SPT activity needs to be elevated to serve that need. However, even small reductions in activity of the downstream metabolic enzymes, or reduced transport of ceramide out of the ER to the site of synthesis of these metabolites in the Golgi, would lead to a catastrophic accumulation of ceramide levels if ceramide synthesis is left unchecked. In this model the ORMDLs serve as essential regulators to enable sphingolipid synthesis to proceed apace, whereas maintaining a nonlethal level of ceramide. Future studies will need to focus on testing this model, establishing the identity of the direct binding component of the ceramide sensor, and gaining structural insight into how SPT activity is regulated.

Experimental procedures

Materials

HeLa cells were purchased from the American Type Tissue Collection. Dulbecco's minimal essential medium, scintillation fluid, Lipofectamine 2000, and Lipofectamine RNAiMax transfection reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). Fetal bovine serum was purchased from Gemini Bioproducts (West Sacramento, CA). The plasmid expressing the fusion protein of SPTLC2/ssSPTa/SPTLC1 was generated as previously described (22). mORMDL3 lacking epitope tags was prepared as described (14). hORMDL3 containing carboxyl-terminal FLAG and Myc epitopes was purchased from Origene Inc. (Rockville, MD). Silencer® Select siRNA oligonucleotides for human ORMDL1–3 (catalog numbers s41258, s26474, and s41260, respectively) and a control siRNA (negative control #2, catalog number 4390846) were from Ambion® (part of Thermo Fisher). Ceramides, sphingosine, 24:1 CoA, Fumonisin B1, myriocin, and sphingomyelin were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, Al) and Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Nonnative stereoisomers of C2 ceramide were from Matreya LLC (State College, PA). C4 phytoceramide was a gift from the Harvey Pollard Lab (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD). ATP, essentially fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), and myriocin were from Sigma. Protease inhibitor mixture (Complete, EDTA-free) was from Roche Applied Science. [3H]Serine was from American Radiochemical Corporation (St. Louis, MO) or PerkinElmer Life Sciences. PVDF was from Bio-Rad. Anti-ORMDL antibody was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA) and was validated by comparison of samples from control cells and cells treated with siRNA directed against all three ORMDL isoforms. Anti-SPTLC1 was from BD Biosciences and was validated by reactivity against samples derived from cells overexpressing the single chain serine palmitoyltransferase construct. Unless otherwise indicated all other reagents were from commercial sources.

Cell culture

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium with 10% fetal calf serum.

Yeast culture

Yeast were grown in 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone (Difco) containing 2% glucose.

Plasmid transfections

For dual transfection of plasmids expressing scSPT and ORMDL3 for the preparation of membranes, HeLa cells were plated in collagen-coated 100-mm tissue culture dishes at 4.7 × 106 cells per plate. The next day cells were transfected with 12 μg/plate of plasmid expressing scSPT and 18 μg/plate of plasmid expressing ORMDL3 utilizing 60 μl/plate of Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions and cultured in penicillin/streptomycin-free medium. Some transfections utilized mORMDL3 lacking epitope tags and some utilized hORMDL3 containing the C-terminal FLAG epitope as indicated in the figure legends. Previous studies have established that these two constructs are functionally equivalent (14). Cells were harvested, as outlined below after 24 h of transfection.

siRNA transfection prior to plasmid transfection

For transfections with either control siRNA or ORMDL1–3 siRNA and subsequent transfection with scSPT and ORMDL: HeLa cells were plated at 106 cells/plate in 100-mm collagen-coated plates. The next day cells were transfected with either 15 nmol/plate of a control siRNA oligonucleotide or 5 nmol each of siRNAs directed against ORMDL1–3 using 24 μl of RNAiMax transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were cultured in penicillin/streptomycin-free medium. The next day cultures were transfected either with scSPT and ORMDL3 (for plates transfected with control siRNA) as described above or with scSPT alone, substituting empty pCMV6-XL5 for ORMDL3 plasmid for cultures transfected with ORMDL siRNA. Cultures were harvested 24 h later as described below.

Preparation of HeLa total lysate

Cells were harvested by trypsinization and washed with ice-cold PBS by centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in 25 mm Tris, 250 mm sucrose, pH 7.5, containing an EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) (400 μl/100-mm plate) and broken by passage 10 times through a 26-gauge needle. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 600 rpm for 10 min in a swinging bucket microcentrifuge (Beckman Allegro25R) at 4 °C. Supernatants were used as “total lysate.”

Preparation of HeLa total membranes

Cells were harvested by trypsinization and washed with ice-cold PBS by centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in swelling buffer (10 mm Tris, 15 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, pH 7.5), 4 ml/10 plates, and incubated for 15 min on ice. 1.3 ml of 1 m sucrose, 17.5 μl of 200 mm EDTA, and 200 μl of a ×25 solution of protease inhibitor mixture were added and cells were broken with 20 strokes of a 7-ml Dounce homogenizer (Kontes, Kimble/Chase, Rockwood, TN). Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 600 rpm for 10 min in a swinging bucket centrifuge ((Beckman Allegro25R). Supernatants were then centrifuged for 20 min at 100,000 rpm in a TLA120.2 ultracentrifuge rotor (Beckman). Pellets were resuspended with 2 ml of 25 mm Tris, 250 mm sucrose, pH 7.5, containing an EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) by Dounce homogenization and finally by 5 passes through a 26-gauge needle and frozen in 100-μl aliquots in liquid nitrogen and storage at −80 °C.

Assay of lipid inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase activity in HeLa cell membranes and lysates

Assays were a modification of an established assay for SPT activity (18). Assays were performed in 2-ml screw-cap microcentrifuge vials (Corning Axygen). For direct addition of short-chain sphingolipids, lysates or membranes (amounts as indicated in figure legends) were preincubated with lipids at the indicated concentrations from 1 mm stock solutions of BSA–lipid complexes in a total volume of 100 μl in 50 mm Hepes, 1 mm DTT, 2 mm EDTA, 40 μm pyridoxyl 5′-phosphate for 40 min at 4 °C. For generation of ceramide in membranes, 50 μg of membranes were incubated for 60 min at 37 °C with 20 μm sphingosine or dihydrosphingosine (as indicated, from a 1 mm stock in 2% fatty acid-free BSA in PBS) and/or 50 μm 24:1 CoA (as indicated, from a 5 mm stock in DMSO) in a final volume of 100 μl in a buffer of 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 25 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA. Assays were initiated by the addition of 100 μl of a solution, pre-warmed to 37 °C of 2 mm serine, 100 μm palmitoyl-CoA, and 20 μCi/ml of [3H]serine. Incubations were continued for 60–90 min (as indicated in figure legends) at 37 °C and terminated by the addition of 400 μl of alkaline MeOH (MeOH + 0.7 g/100 ml of KOH) and vortexing. 100 μl of CHCl3 was then added, followed by vortexing and brief centrifugation. 500 μl of CHCl3 was then added followed by 300 μl of alkaline H2O (100 μl of 2 n NH3OH) and 100 μl of 2 n NH3OH to break the phases. Tubes were vigorously vortexed, then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 min in a microcentrifuge (Beckman) to separate the phases. The upper, aqueous phase was aspirated. The lower, organic phase was washed twice with 1 ml of alkaline H2O by vortexing, centrifugation, and aspiration of the upper phase. 350 μl of the organic phase was dried in scintillation minivials (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), under N2, 7 ml of scintillation fluid was added (Ecoscint, National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA, or BetaMax ES, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH)) and vials were counted for 5 min (PerkinElmer Tricarb 2910 or Beckman-Coulter LS6500). BSA–lipid complexes were prepared by the addition of lipids from 20 mm methanol solutions (sonicated) into 20 mg/ml of essentially fatty acid-free BSA in PBS with vortexing.

Assay of lipid inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase activity in intact HeLa cells

HeLa cells were plated on collagen-coated 24-well plates at 7 × 104 cells/well in antibiotic-free DMEM. The next day, cells were transfected with either 15 nmol/well of a control siRNA oligonucleotide or 5 nmol each of siRNAs directed against ORMDL1–3 using 0.6 μl/well of RNAiMax transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours following siRNA-mediated knockdown of ORMDL1–3, cells were treated with C8 ceramide as indicated, 10 μm final concentration (from a 1 mm solution complexed with 2% fatty acid-free BSA), in 300 μl/well antibiotic-free culture medium for 2 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For some experiments, untransfected HeLa cells were treated overnight with either vehicle (DMSO) or Fumonisin B1 (50 μm final concentration) in complete medium. The next day the cells were treated with C8 ceramide or d-erythro-sphingosine as indicated, 10 μm final concentration (from a 1 mm solution complexed with 2% fatty acid-free BSA), in 300 μl/well of antibiotic-free culture medium for 2 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Following all lipid treatments, medium was removed and cells were washed with PBS. Serine-free media containing 10 μCi/ml of [3H]serine was used for radiolabeling cells at 200 μl/well volume. Cells were labeled for 60 or 90 min after which labeling media was removed and cells were washed once with PBS. After washing, 200 μl/well of 1× PBS was placed on cells. For lipids, cells were harvested directly on the plates by adding 400 μl/well of alkaline methanol (MeOH + 0.7 g/100 ml of KOH). The cell/PBS/methanol mix was transferred to 2-ml screw-cap tubes and the final lipid extraction steps were conducted as described above. For total protein estimation per well and Western blot analysis, cells were lifted with trypsinization, pelleted, then resuspended in lysis buffer as detailed above under “preparation of total lysates.”

Assay of lipid inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase activity in permeabilized HeLa cells

HeLa cells were plated on collagen-coated 24-well plates and subjected to siRNA-mediated knockdown of ORMDLs1–3 exactly as described above for intact cells. Forty-eight hours following siRNA transfection, media was removed and cells were washed with PBS. The plasma membrane was then permeabilized by adding 200 μl/well of Opti-MEM (Gibco) containing 200 μg/ml of digitonin (Sigma); cells were incubated for 3 min at 37 °C. The permeabilization medium was removed and cells were washed with PBS. 200 μl/well of preincubation medium (50 mm HEPES pH 8.0, 1 mm EDTA, 20 μm pyridoxyl 5′-phosphate) was added with or without 10 μm C8 ceramide (added from a 1 mm stock complexed to 2% fatty acid-free BSA in PBS) and/or 1 μm myriocin. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, then an additional 200 μl/well of incubation medium was added without removing the preincubation medium. Incubation medium was identical to the preincubation medium with the addition of (final concentration) 2 μCi of [3H]serine/well, 1 mm cold serine, and 50 μm palmitoyl-CoA. Cells were then incubated for an additional 60 min. Cells were then extracted without removing the incubation medium by a modification of the method of Rutti and colleagues (18) by adding 400 μl/well of alkaline methanol (0.7 KOH, 100 ml MeOH) and transferring cells into a 2-ml screw-cap microcentrifuge tube. The remainder of lipid extraction steps were exactly as detailed above.

Yeast microsomal membrane

Yeast strains

The following yeast strains were used: TDYG4a: MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ (Dunn Lab); TDYK1005: MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 orm1Δ::Kan (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL); TDYK1006: MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 orm2Δ::Kan (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL); and ACX164-1C: MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 orm1Δ::Nat orm2Δ::HIS3 (A. Chang Lab, University of Michigan (12)).

Preparation

Cells were harvested at exponential phase, pelleted at 5,000 × g, washed with water, repelleted, and then washed with TEGM buffer. The cell pellets were resuspended in TEGM (0.05 m Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml of leupeptin, 1 μg/ml of pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml of aprotinin) buffer at 1 ml/50 OD cells, and glass beads (0.5 mm diameter) were added to within ∼1/4 inch from the meniscus. The cells were disrupted by vortexing 4 × 1 min with 1 min on ice between. The lysate was transferred to a new tube with extensive washing of the beads and pelleted at 8,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The pellet was resuspended by Dounce homogenization in 10 volumes of TEGM buffer and repelleted at 100,000 × g. The final membrane pellet was resuspended in TEGM buffer containing 33% glycerol and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad dye reagent with IgG as standard.

Assay of lipid inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase activity in yeast cell membranes

Ceramides were dissolved in ethanol at 10 mm and complexed at 0.2 mm with 0.2 mm BSA in water. The reaction was initiated by adding 100 μg of microsomal membrane to a reaction mixture (final volume 300 μl) containing 50 mm Hepes, pH 8.1, 50 μm pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, 2.5 mm serine, 20 μCi of [3H]serine, 25 μm palmitoyl-CoA, and 30 μl of a solution of 0.2 mm BSA, 0.2 mm ceramide. After 12 min NH4OH was added to a final concentration of 0.25 m, followed by 1.5 ml of CHCl3/methanol (1:2), and the mixture was vortexed. Long chain bases were extracted by adding 1 ml of CHCl3 and 2 ml of 0.5 m NH4OH, vortexing and centrifuging briefly. The upper aqueous layer was aspirated off and the lower layer was washed with 2 ml of 30 mm KCl and centrifuged. The washing was repeated twice and 1 ml of the sample was dried and counted.

SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis and immunoblotting

Laemmli sample buffer was added to samples and samples were incubated at 100 °C for 5 min and then applied to 1.5-mm thick 12% polyacrylamide gels and electrophoresed at 50 mA for ∼45 min. Proteins were transferred to PVDF for 1 h at 250 mA. Blots were blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dry milk (w/v) in TBS, 0.1% Tween 20, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies in 5% nonfat dry milk (w/v) in TBS, 0.1% Tween 20 at 1:1,000 dilutions. Membranes were then washed 3 × for 15 min at room temperature with TBS, 0.1% Tween 20 with rocking. Secondary, horseradish peroxidase-coupled antibodies at 1:10,000 dilution in 1% nonfat dry milk (w/v) in TBS, 0.1% Tween 20 were added for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were then washed for 3 × 15 min at room temperature with TBS, 0.1% Tween 20 and visualized with ECL-Plus (GE Healthcare Lifesciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions using HyblotCL Film (Denville Scientific, Meuchen, NJ).

Author contributions

D. L. D., K. G., J. S., T. M. D., and B. W. W. data curation; D. L. D., T. M. D., and B. W. W. supervision; D. L. D., K. G., J. S., T. M. D., and B. W. W. investigation; D. L. D., K. G., J. S., T. M. D., and B. W. W. methodology; D. L. D., K. G., J. S., T. M. D., and B. W. W. writing-review and editing; K. G., T. M. D., and B. W. W. formal analysis; T. M. D. and B. W. W. conceptualization; T. M. D. and B. W. W. project administration; B. W. W. funding acquisition; B. W. W. writing-original draft.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Wattenberg laboratory for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Bridge Grant from the University of Louisville School of Medicine (to B. W.), the James Graham Brown Cancer Center (to B. W.), National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL131340 (to B. W.), and National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense Grant HL14-007.001/BIO-71-8822 (to T. M. D.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- LCB

- long chain bases

- SPT

- serine palmitoyltransferase

- scSPT

- single chain SPT construct (SPTLC2–ssSPTa–SPTLC1 as a fusion protein in a single polypeptide)

- C(X)

- (phyto)ceramide-ceramide or phytoceramide, where X = acyl chain length

- TBS

- Tris-buffered saline

- PVDF

- polyvinylidene difluoride.

References

- 1. Barenholz Y. (2004) Sphingomyelin and cholesterol: from membrane biophysics and rafts to potential medical applications. Subcell. Biochem. 37, 167–215 10.1007/978-1-4757-5806-1_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goñi F. M., and Alonso A. (2006) Biophysics of sphingolipids I. Membrane properties of sphingosine, ceramides and other simple sphingolipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1902–1921 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hannun Y. A., and Obeid L. M. (2002) The ceramide-centric universe of lipid-mediated cell regulation: stress encounters of the lipid kind. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25847–25850 10.1074/jbc.R200008200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maceyka M., Harikumar K. B., Milstien S., and Spiegel S. (2012) Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and its role in disease. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 50–60 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Slotte J. P. (2013) Biological functions of sphingomyelins. Prog. Lipid Res. 52, 424–437 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breslow D. K., Collins S. R., Bodenmiller B., Aebersold R., Simons K., Shevchenko A., Ejsing C. S., and Weissman J. S. (2010) Orm family proteins mediate sphingolipid homeostasis. Nature 463, 1048–1053 10.1038/nature08787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mandon E. C., van Echten G., Birk R., Schmidt R. R., and Sandhoff K. (1991) Sphingolipid biosynthesis in cultured neurons: down-regulation of serine palmitoyltransferase by sphingoid bases. Eur. J. Biochem. 198, 667–674 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Siow D. L., and Wattenberg B. W. (2012) Mammalian ORMDL proteins mediate the feedback response in ceramide biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40198–40204 10.1074/jbc.C112.404012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanada K. (2003) Serine palmitoyltransferase, a key enzyme of sphingolipid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1632, 16–30 10.1016/S1388-1981(03)00059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harrison P. J., Dunn T. M., and Campopiano D. J. (2018) Sphingolipid biosynthesis in man and microbes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 35, 921–954 10.1039/C8NP00019K [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han S., Lone M. A., Schneiter R., and Chang A. (2010) Orm1 and Orm2 are conserved endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins regulating lipid homeostasis and protein quality control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5851–5856 10.1073/pnas.0911617107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu M., Huang C., Polu S. R., Schneiter R., and Chang A. (2012) Regulation of sphingolipid synthesis through Orm1 and Orm2 in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 125, 2428–2435 10.1242/jcs.100578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hjelmqvist L., Tuson M., Marfany G., Herrero E., Balcells S., and Gonzàlez-Duarte R. (2002) ORMDL proteins are a conserved new family of endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins. Genome Biol. 3, research0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Siow D., Sunkara M., Dunn T. M., Morris A. J., and Wattenberg B. (2015) ORMDL/serine palmitoyltransferase stoichiometry determines effects of ORMDL3 expression on sphingolipid biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 56, 898–908 10.1194/jlr.M057539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Han G., Gupta S. D., Gable K., Bacikova D., Sengupta N., Somashekarappa N., Proia R. L., Harmon J. M., and Dunn T. M. (2019) The ORMs interact with transmembrane domain 1 of Lcb1 and regulate serine palmitoyltransferase oligomerization, activity and localization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1864, 245–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roelants F. M., Breslow D. K., Muir A., Weissman J. S., and Thorner J. (2011) Protein kinase Ypk1 phosphorylates regulatory proteins Orm1 and Orm2 to control sphingolipid homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 19222–19227 10.1073/pnas.1116948108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis D., Kannan M., and Wattenberg B. (2018) Orm/ORMDL proteins: gate guardians and master regulators. Adv. Biol. Regul. 70, 3–18 10.1016/j.jbior.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rütti M. F., Richard S., Penno A., von Eckardstein A., and Hornemann T. (2009) An improved method to determine serine palmitoyltransferase activity. J. Lipid Res. 50, 1237–1244 10.1194/jlr.D900001-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laviad E. L., Albee L., Pankova-Kholmyansky I., Epstein S., Park H., Merrill A. H. Jr., and Futerman A. H. (2008) Characterization of ceramide synthase 2: tissue distribution, substrate specificity, and inhibition by sphingosine 1-phosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5677–5684 10.1074/jbc.M707386200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geeraert L., Mannaerts G. P., and van Veldhoven P. P. (1997) Conversion of dihydroceramide into ceramide: involvement of a desaturase. Biochem. J. 327, 125–132 10.1042/bj3270125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Michel C., van Echten-Deckert G., Rother J., Sandhoff K., Wang E., and Merrill A. H. Jr. (1997) Characterization of ceramide synthesis: a dihydroceramide desaturase introduces the 4,5-trans-double bond of sphingosine at the level of dihydroceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 22432–22437 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gable K., Gupta S. D., Han G., Niranjanakumari S., Harmon J. M., and Dunn T. M. (2010) A disease-causing mutation in the active site of serine palmitoyltransferase causes catalytic promiscuity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22846–22852 10.1074/jbc.M110.122259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harmon J. M., Bacikova D., Gable K., Gupta S. D., Han G., Sengupta N., Somashekarappa N., and Dunn T. M. (2013) Topological and functional characterization of the ssSPTs, small activating subunits of serine palmitoyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10144–10153 10.1074/jbc.M113.451526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun Y., Miao Y., Yamane Y., Zhang C., Shokat K. M., Takematsu H., Kozutsumi Y., and Drubin D. G. (2012) Orm protein phosphoregulation mediates transient sphingolipid biosynthesis response to heat stress via the Pkh-Ypk and Cdc55-PP2A pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 2388–2398 10.1091/mbc.e12-03-0209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Castro B. M., Prieto M., and Silva L. C. (2014) Ceramide: a simple sphingolipid with unique biophysical properties. Prog. Lipid Res. 54, 53–67 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hanada K., Hara T., Nishijima M., Kuge O., Dickson R. C., and Nagiec M. M. (1997) A mammalian homolog of the yeast LCB1 encodes a component of serine palmitoyltransferase, the enzyme catalyzing the first step in sphingolipid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32108–32114 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Han G., Gupta S. D., Gable K., Niranjanakumari S., Moitra P., Eichler F., Brown R. H. Jr., Harmon J. M., and Dunn T. M. (2009) Identification of small subunits of mammalian serine palmitoyltransferase that confer distinct acyl-CoA substrate specificities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8186–8191 10.1073/pnas.0811269106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gururaj C., Federman R., and Chang A. (2013) Orm proteins integrate multiple signals to maintain sphingolipid homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 20453–20463 10.1074/jbc.M113.472860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimobayashi M., Oppliger W., Moes S., Jenö P., and Hall M. N. (2013) TORC1-regulated protein kinase Npr1 phosphorylates Orm to stimulate complex sphingolipid synthesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 870–881 10.1091/mbc.e12-10-0753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gupta S. D., Gable K., Alexaki A., Chandris P., Proia R. L., Dunn T. M., and Harmon J. M. (2015) Expression of the ORMDLS, modulators of serine palmitoyltransferase, is regulated by sphingolipids in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 90–98 10.1074/jbc.M114.588236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cai L., Oyeniran C., Biswas D. D., Allegood J., Milstien S., Kordula T., Maceyka M., and Spiegel S. (2016) ORMDL proteins regulate ceramide levels during sterile inflammation. J. Lipid Res. 57, 1412–1422 10.1194/jlr.M065920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang S., Robinet P., Smith J. D., and Gulshan K. (2015) ORMDL orosomucoid-like proteins are degraded by free-cholesterol-loading-induced autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 3728–3733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu L. K., Choudhary V., Toulmay A., and Prinz W. A. (2017) An inducible ER-Golgi tether facilitates ceramide transport to alleviate lipotoxicity. J. Cell Biol. 216, 131–147 10.1083/jcb.201606059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang X. H., Shu J., Jiang C. M., Zhuang L. L., Yang W. X., Zhang H. W., Wang L. L., Li L., Chen X. Q., Jin R., and Zhou G. P. (2017) Mechanisms and roles by which IRF-3 mediates the regulation of ORMDL3 transcription in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87, 8–17 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ha S. G., Ge X. N., Bahaie N. S., Kang B. N., Rao A., Rao S. P., and Sriramarao P. (2013) ORMDL3 promotes eosinophil trafficking and activation via regulation of integrins and CD48. Nat. Commun. 4, 2479 10.1038/ncomms3479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller M., Tam A. B., Cho J. Y., Doherty T. A., Pham A., Khorram N., Rosenthal P., Mueller J. L., Hoffman H. M., Suzukawa M., Niwa M., and Broide D. H. (2012) ORMDL3 is an inducible lung epithelial gene regulating metalloproteases, chemokines, OAS, and ATF6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16648–16653 10.1073/pnas.1204151109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oyeniran C., Sturgill J. L., Hait N. C., Huang W. C., Avni D., Maceyka M., Newton J., Allegood J. C., Montpetit A., Conrad D. H., Milstien S., and Spiegel S. (2015) Aberrant ORM (yeast)-like protein isoform 3 (ORMDL3) expression dysregulates ceramide homeostasis in cells and ceramide exacerbates allergic asthma in mice. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 1035–1046.e1036 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kihara A. (2016) Synthesis and degradation pathways, functions, and pathology of ceramides and epidermal acylceramides. Prog. Lipid Res. 63, 50–69 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmitt S., Castelvetri L. C., and Simons M. (2015) Metabolism and functions of lipids in myelin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851, 999–1005 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]