Abstract

Platelet degranulation, a form of regulated exocytosis, is crucial for hemostasis and thrombosis. Exocytosis in platelets is mediated by SNARE proteins, and in most mammalian cells this process is controlled by Munc18 (mammalian homolog of Caenorhabditis elegans uncoordinated gene 18) proteins. Platelets express all Munc18 paralogs (Munc18-1, -2, and -3), but their roles in platelet secretion and function have not been fully characterized. Using Munc18-1, -2, and -3 conditional knockout mice, here we deleted expression of these proteins in platelets and assessed granule exocytosis. We measured products secreted by each type of platelet granule and analyzed EM platelet profiles by design-based stereology. We observed that the removal of Munc18-2 ablates the release of alpha, dense, and lysosomal granules from platelets, but we found no exocytic role for Munc18-1 or -3 in platelets. In vitro, Munc18-2–deficient platelets exhibited defective aggregation at low doses of collagen and impaired thrombus formation under shear stress. In vivo, megakaryocyte-specific Munc18-2 conditional knockout mice had a severe hemostatic defect and prolonged arterial and venous bleeding times. They were also protected against arterial thrombosis in a chemically induced model of arterial injury. Taken together, our results indicate that Munc18-2, but not Munc18-1 or Munc18-3, is essential for regulated exocytosis in platelets and platelet participation in thrombosis and hemostasis.

Keywords: exocytosis, SNARE proteins, platelet, hemostasis, thrombosis, secretion, Munc18

Introduction

Exocytosis of alpha, dense, and lysosomal granules from platelets plays important roles in hemostasis, thrombosis, and inflammatory processes. Alpha granules contain soluble proteins (e.g. von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen) and membrane-associated proteins (e.g. P-selectin and integrins αIIb and β3) that propagate platelet adhesion and aggregation (1). Dense granules store ADP, a key autocrine and paracrine agonist for platelet activation, and other small molecules (e.g. serotonin and ATP) (2). The function of lysosomal granule contents remains speculative (3).

During exocytosis, the membrane of a secretory vesicle (e.g. platelet granule) fuses with the plasma membrane, allowing the release of its soluble contents into the extracellular space and the incorporation of its membrane-associated proteins into the plasma membrane. SNARE3 (soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) proteins are required for this process. SNARE proteins on the secretory granule membrane (vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)) and plasma membrane (syntaxin (Stx) and synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP25)) form a highly stable coiled-coil structure (trans-SNARE complex) that pulls apposing membranes together during fusion (4, 5). Trans-SNARE complex formation and membrane fusion during exocytosis are regulated by Munc18 (mammalian homolog of Caenorhabditis elegans uncoordinated gene 18) proteins (6). Munc18 keeps Stx in a “closed” conformation that hinders the formation of nonproductive, ectopic, SNARE complexes (7). Interactions between Munc13 and Munc18 catalyze the transition of Stx to an “open” conformation and favor the association of the SNARE domain of Stx with those of VAMP and SNAP25 (8, 9). Finally, Munc18 interacts directly with the trans-SNARE complex to stabilize it and facilitate membrane fusion (10–12).

Platelets express Munc18-1, -2, and -3, proteins (13, 14) encoded by the Stx-binding protein (Stxbp) 1, 2, and 3 genes, respectively. One study suggests that Munc18-1 controls exocytosis in platelets (14). Munc18-3 was originally isolated from platelets and called platelet Sec1 protein (15). Earlier reports on permeabilized platelets found that Munc18-3 contributes to platelet secretion by interacting with Stx4 (13). Another study used Munc18-3 global knockout (KO) mice, but only heterozygotes could be studied because homozygosity is lethal (16, 17), and the conclusion was that haploinsufficiency for Munc18-3 has no effects on platelet exocytosis (18). Mutations in the gene encoding Munc18-2 cause familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 (FHL-5), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by an inflammatory response mediated by T-lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and macrophages (19). Platelets from a biallelic and a heterozygous FHL-5 patient had severe and intermediate exocytic defects, respectively, suggesting that Munc18-2 is a limiting factor in platelet secretion (20).

We investigated the role of all three Munc18 paralogs in platelet secretion and platelet-dependent pathophysiology. Although the absence of Munc18-1 or Munc18-3 had no effects on exocytosis, the lack of Munc18-2 suppressed the release of alpha, dense, and lysosomal platelet granules almost completely, impairing platelet aggregation and thrombus formation in vitro. Finally, using megakaryocyte-specific KO mice, we proved that Munc18-2 in platelets, and not in other tissues, is required for venous and arterial hemostasis and for arterial thrombosis.

Results

Expression and targeting of Munc18 proteins in platelets

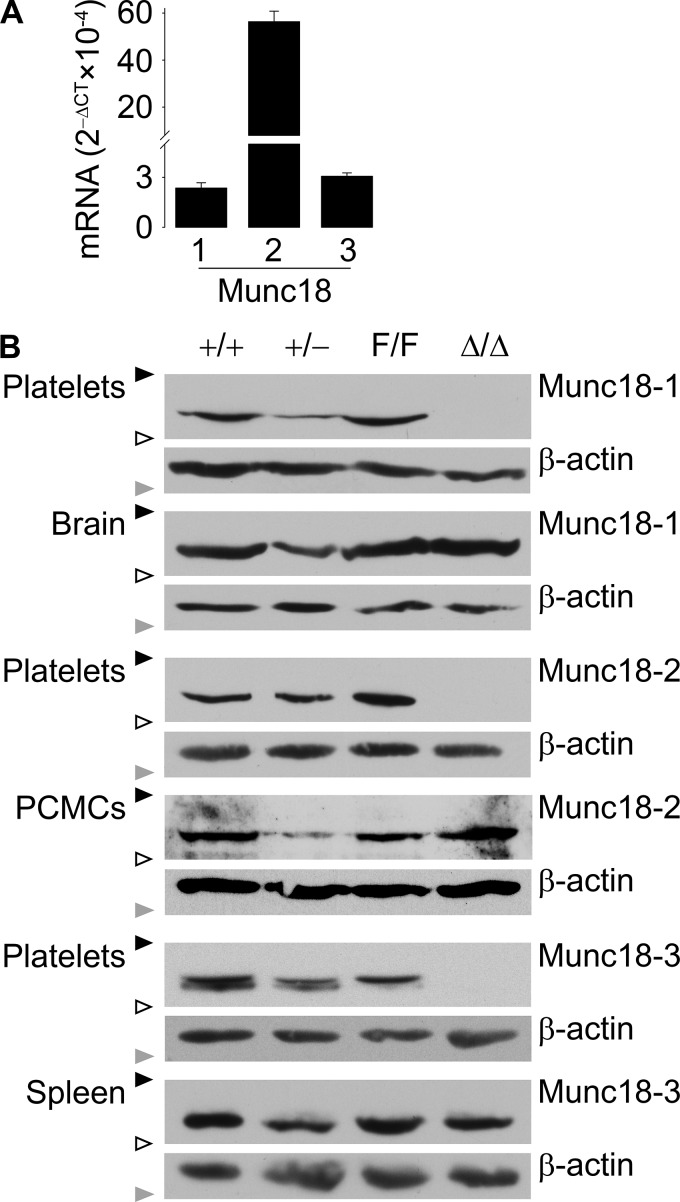

By RT-qPCR, we found that C57BL/6J platelets express transcripts for Munc18-1, -2, and -3. Munc18-2 was the most abundant (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Expression and deletion of Munc18 proteins. A, RT-qPCR of all Munc18 proteins relative to β-actin in C57BL/6J platelets. n = 3–4; bar, mean; error bar, S.E. B, representative immunoblots of platelet and control tissue lysates probed with anti-mouse Munc18-1, Munc18-2, or Munc18-3 antibody. Bands for the three Munc18 isoforms ran at ∼67 kDa. β-Actin (∼42 kDa) was used as loading control. PCMCs, peritoneal cell-derived mast cells; black triangles, 75-kDa molecular mass marker; white triangles, 50-kDa molecular mass marker; gray triangles, 37-kDa molecular mass marker.

To study the role of these proteins in platelet exocytosis and function, we selectively deleted their genes in megakaryocytes using the Cre-loxP system. We used conditional KO mice for the three genes (17, 21, 22) to generate global heterozygote (+/−) and megakaryocyte/platelet-specific (Δ/Δ) KO mice. Global homozygous KO mice for the three genes (−/−) were not viable (17, 22–24).

Immunoblots of tissues and platelets confirmed that platelets express the three Munc18 proteins (Fig. 1B). They also showed that mice carrying alleles flanked by two loxP sequences (“floxed” or F/F) and WT controls (+/+) expressed similar levels of each Munc18 protein. Finally, all three Δ/Δ mouse lines lacked expression of the targeted Munc18 protein only in platelets, whereas its expression in other tissues was comparable with that of the corresponding F/F littermates.

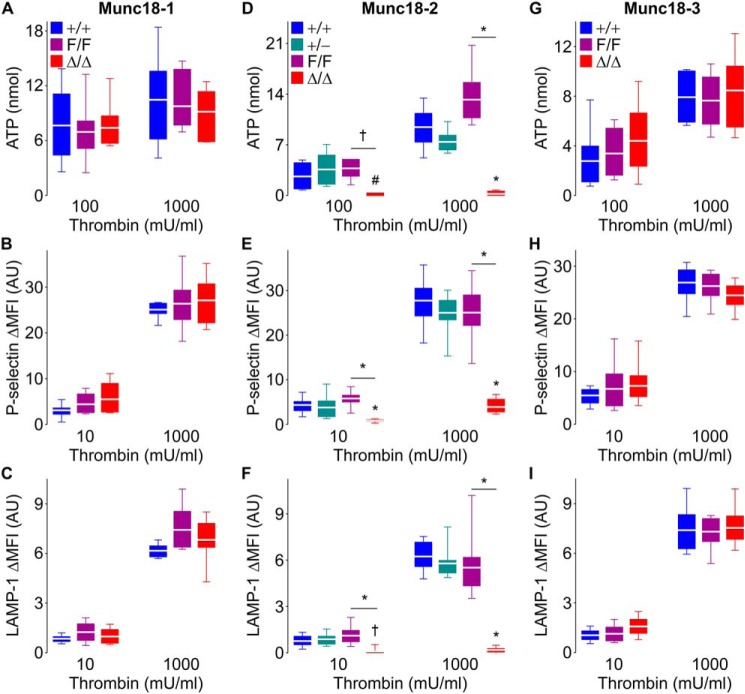

Munc18-2 regulates platelet exocytosis

To study how different Munc18 proteins contribute to platelet granule secretion, we assessed exocytosis of each type of platelet granule. We measured the release of ATP (dense granules) and the translocation of P-selectin (alpha granules) and LAMP-1 (lysosomal granules) to the plasma membrane upon platelet activation. We stimulated platelets with a low and high dose of thrombin as described previously (25). We observed that Munc18-2 deletion severely impaired exocytosis of dense, alpha, and lysosomal granules (Fig. 2, D–F, and Figs. S1 and S2). The signal for our three markers of exocytosis was barely detectable even with high-dose stimulation. Munc18-2 heterozygote platelets had a minor exocytic defect that failed to reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Deletion of Munc18-2 impairs dense, alpha, and lysosomal granule release in thrombin-stimulated platelets. Samples from Munc18-1 (A–C), Munc18-2 (D–F), and Munc18-3 (G–I) mutant mice were stimulated with thrombin. A, D, and G, ATP release (dense granules) measured by luminometry in whole blood. n = 6–9. B and C, E and F, and H and I, mean fluorescence intensity over baseline (ΔMFI) of P-selectin (alpha granules) (B, E, and H) and LAMP-1 (lysosomal granules) (C, F, and I) translocated to the surface of washed platelets measured by flow cytometry. n = 8–10. Color legends in A, D, and G apply to A–C, D–F, and G–I, respectively. White line, mean; box, 25th–75th percentile; whiskers, 5th–95th percentile. #, p < 0.05; †, p ≤ 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.001; comparisons are to WT controls (+/+) unless otherwise specified.

Platelets lacking Munc18-1 or Munc18-3 showed no exocytic defects (Fig. 2, A–C and G–I). We did not test exocytosis in platelets from heterozygote Munc18-1 and -3 mice given that full deletion did not produce a secretory phenotype. For the same reason, we opted not to study any Munc18-1 and Munc18-3 mutants in subsequent functional experiments.

We confirmed the failure in alpha granule release in platelets lacking Munc18-2 by measuring the secretion of a soluble granule content, PF4 (platelet factor 4), instead of translocation of a membrane protein (P-selectin) (Fig. 3, B and C). Given the severe exocytic defect observed in thrombin-stimulated Munc18-2–deficient platelets, we decided to assess potential agonist dependence by studying exocytosis in response to a different stimulus. We measured the secretion of ATP (dense granules) and PF4 (alpha granules) following collagen stimulation and found that the deletion of Munc18-2 impaired their release (Fig. 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Defective exocytosis in Munc18-2–deficient platelets is independent of the agonist used and cannot be rescued by exogenous ADP. Samples from Munc18-2 mutant mice were stimulated with collagen (10 μg/ml unless otherwise specified) or thrombin (1 unit/ml) in the absence or presence of ADP (10 μm). A, ATP release (dense granules) measured by luminometry in whole blood. n = 6. B and C, PF4 release (alpha granules) measured by ELISA. n = 5–6. D and E, mean fluorescence intensity over baseline (ΔMFI) of P-selectin (alpha granules) (D) and LAMP-1 (lysosomal granules) (E) translocated to the surface of washed platelets measured by flow cytometry. n = 6. The color legend in A applies to all panels. White line, mean; box, 25th–75th percentile; whiskers, 5th–95th percentile. †, p ≤ 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.001; comparisons are to WT controls (+/+) unless otherwise specified.

Alterations in ADP release from dense granules can indirectly affect the exocytosis of other platelet granules (25). To test whether the defects observed in alpha and lysosomal granule exocytosis from Munc18-2Δ/Δ platelets was indirect, we added exogenous ADP to the stimulated platelets and found that it could rescue neither the secretion of PF4 (Fig. 3, B and C) nor the translocation of P-selectin (Fig. 3D) or LAMP-1 (Fig. 3E). A summary of all secretion assays is presented in Table S1.

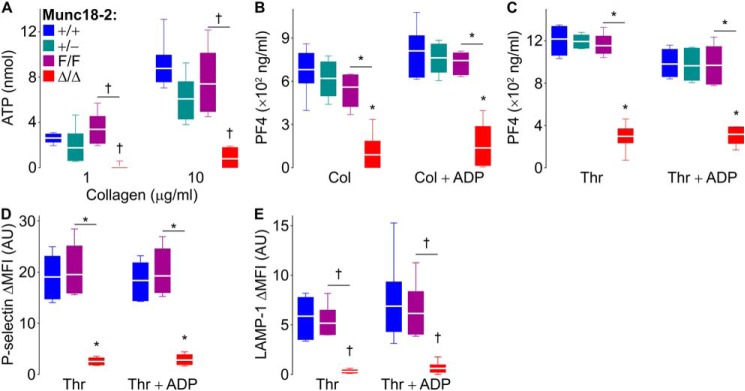

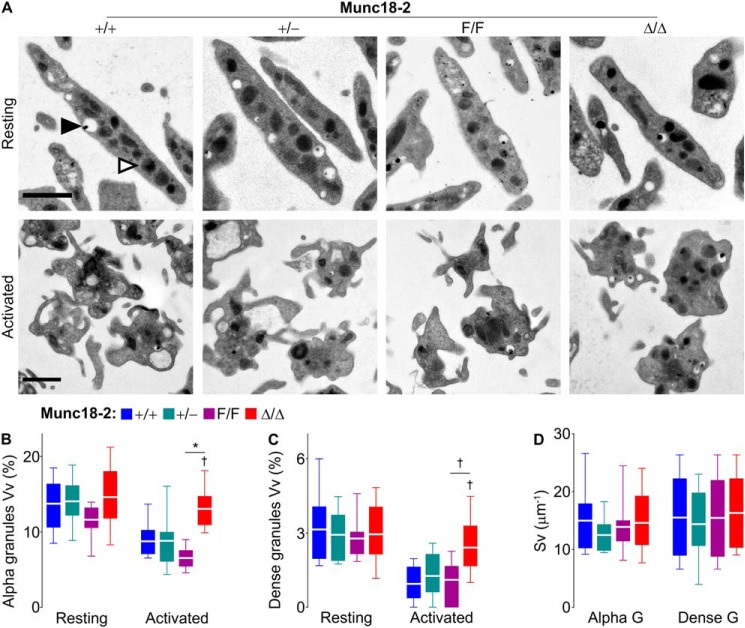

Munc18-2 is required for platelet granule release but not for granule biogenesis

To rule out the possibility that the abnormal secretion observed in platelets lacking Munc18-2 was secondary to an impairment in platelet granule formation, we analyzed the resting platelets by electron microscopy (EM) (Fig. 4A, top row). Morphologic analysis of unstimulated platelets revealed no differences in the volume densities and surface densities of alpha or dense granules among all genotypes (Fig. 4, B–D). Assuming that most granules are almost spherical, the simultaneous stability of these two stereology values indicates that there are no changes in the number or size of granules (26, 27).

Figure 4.

Deletion of Munc18-2 impairs granule release but not granule biogenesis. Washed platelets from Munc18-2 mutant mice were activated with thrombin (0.1 unit/ml). A, representative EM cell profiles before (top row) and after (bottom row) stimulation. Black triangle, example of a dense granule; white triangle, example of an alpha granule; scale bars, 1 μm. B–D, values obtained by design-based stereology from ∼200 platelet profiles from three animals of each genotype. B and C, volume density (Vv) of alpha granules (B) and dense granules (C) in resting and activated platelets. D, surface density (Sv) for both types of granules in resting platelets. Color legend in B applies to B–D. White line, mean; box, 25th–75th percentile; whiskers, 5th–95th percentile. †, p ≤ 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.001; comparisons are to WT controls (+/+) unless otherwise specified.

We then used EM and stereology on stimulated platelets to confirm morphometrically what we had found in our secretion assays. Qualitatively, we observed the characteristic shape changes associated with platelet activation after exposure to thrombin in all genotypes (Fig. 4A, bottom row). Quantitatively, the volume density of the alpha and dense granules was expected to decrease as a result of the loss of granules through exocytosis following stimulation. However, Munc18-2–deficient platelets lost almost no alpha (Fig. 4B) or dense (Fig. 4C) granules. Once again, Munc18-2 heterozygote platelets showed no defect in degranulation.

Munc18-2 is indispensable for platelet aggregation and thrombus formation

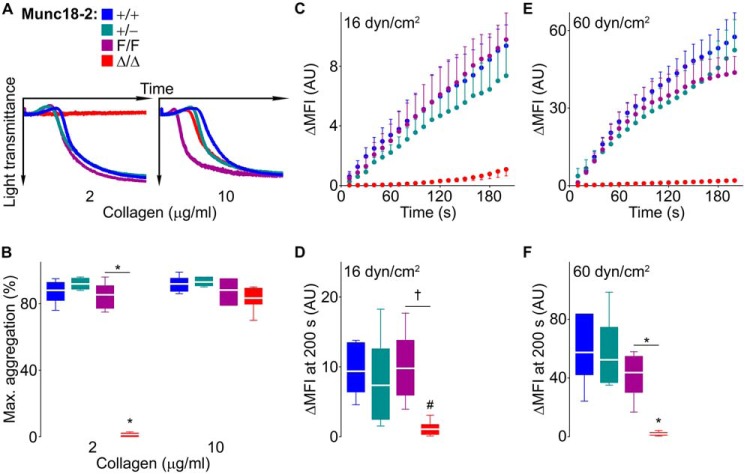

To determine how the absence of Munc18-2 would affect platelet function, we first studied platelet aggregation. Interestingly, platelets not expressing Munc18-2 could form aggregates only when a high dose of collagen was used (Fig. 5, A and B). The flat aggregometry recordings indicate that Munc18-2–deficient platelets do not even undergo shape changes when stimulated with a low dose of collagen.

Figure 5.

Deletion of Munc18-2 impedes platelet aggregation and interferes with thrombus formation in vitro. A and B, samples from Munc18-2 mutant mice were stimulated with collagen. Representative tracings of platelet aggregation (A) and maximum aggregation measured by light transmittance (B) on platelet-rich plasma. n = 6. C–F, whole blood was labeled fluorescently and perfused over collagen-coated plates at low (C and D) or high (E and F) shear stress. Thrombus buildup (C and E) was monitored by the change in fluorescence intensity over baseline (ΔMFI) and compared at 200 s (D and F). n = 5–8; AU, arbitrary units. The color legend in A applies to all panels. Circle or white line, mean; error bar, S.E.; box, 25th-75th percentile; whiskers, 5th–95th percentile. #, p < 0.05; †, p ≤ 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.001; comparisons are to WT controls (+/+) unless otherwise specified.

We then assessed platelet behavior under shear stress in a collagen-coated flow chamber using fluorescently labeled whole blood. We observed a marked difference in the rise of fluorescence in samples from Munc18-2Δ/Δ mice, indicating a severe defect in thrombus formation in Munc18-2–deficient platelets independent of the degree of shear stress employed (Fig. 5, C–F). The slight rise in the fluorescence signal from Munc18-2Δ/Δ samples, which is better seen using a different scale (Fig. S3), corresponds to the binding of platelets to the layer of collagen.

Lack of Munc18-2 in platelets disrupts hemostasis and thrombosis

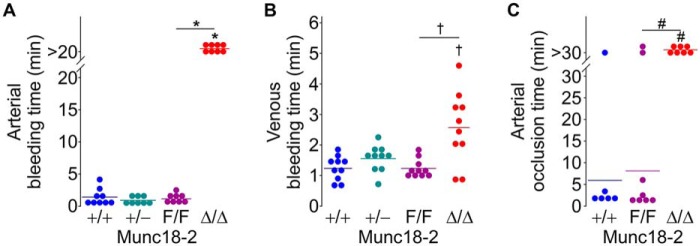

We used two tail bleeding tests to study hemostasis. Using the classic transection model, which depends largely on arterial bleeding, we found that all of the Munc18-2Δ/Δ mice could not stop bleeding and had to be euthanized after 20 min (Fig. 6A). We then used a device we had described previously that reproducibly makes a 0.8-mm–deep dorsal cut at the level where the mouse tail is 3.8 mm in diameter (25), sectioning only the dorsal venous plexus to induce venous bleeding, and observed that Munc18-2Δ/Δ mice bled significantly longer than the controls (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Deletion of Munc18-2 in platelets disrupts hemostasis and thrombosis. A and B, tail bleeding times that depends mostly on arterial (A) and venous (B) bleeding were recorded in Munc18-2 mutant mice. n = 8–10. C, time to carotid occlusion after applying FeCl3 abluminally for 3 min. n = 6–8. Circle, individual mouse; horizontal line, mean. #, p < 0.05; †, p ≤ 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.001; comparisons are to WT controls (+/+) unless otherwise specified.

Finally, we assessed thrombosis in vivo with the FeCl3 model of carotid artery thrombosis (25, 28). Although most Munc18-2+/+ and Munc18-2F/F mice showed arterial occlusion in less than 5 min, we did not observe any vessel occlusion in Munc18-2Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 6C). None of these findings was caused by abnormal numbers of circulating platelets in the mutant mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Blood cell counts in Munc18-2 mutant mice

Results are mean ± S.E. from 11 mice of each genotype. No significant differences were found among mice of all genotypes in any category.

| Munc18-2+/+ | Munc18-2+/− | Munc18-2F/F | Munc18-2Δ/Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red blood cells (×1012/liter) | 8.6 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.13 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 8.2 ± 0.2 |

| White blood cells (×109/liter) | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 5.8 ± 0.4 |

| Lymphocytes | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.4 |

| Monocytes | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Granulocytes | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| Platelets (×109/liter) | 700 ± 55 | 685 ± 49 | 764 ± 22 | 746 ± 35 |

Discussion

The SM (Sec1/Munc18-like) family of proteins is crucial for membrane trafficking in eukaryotic cells. In mammals, the SM family members involved in regulated exocytosis are Munc18-1, -2, and -3, and we found that mouse platelets expressed all of them (Fig. 1).

Besides exocytosis in neurons (23) and neuroendocrine cells (29, 30), Munc18-1 regulates the baseline secretion of mucins in airway epithelial secretory cells (22). Other cells of hematopoietic origin such as mast cells also express Munc18-1, and initial experiments using siRNA suggested that Munc18-1 is required for different forms of exocytosis in these cells (31, 32), but in a recent study using gene deletion we disprove these conclusions (17). Similarly, platelets express Munc18-1, and previous studies using inhibitory peptides on permeabilized platelets suggested that Munc18-1 is required for alpha granule release (14). The fact that we could not find any defect on the release of any type of granule when we eliminated expression of Munc18-1 in platelets is a strong argument against that statement (Fig. 2).

The interaction between Munc18-3 and its cognate, Stx4, which is essential for exocytosis in pancreatic β-cells (33), adipocytes (16), skeletal muscle (34), and neutrophils (35), has been thought to mediate platelet granule secretion. Early studies on permeabilized platelets found that targeting Munc18-3 (13, 14) or Stx4 (36–38) could impair platelet exocytosis. Others tried more definitive experiments using platelets from Munc18-3 heterozygote global KO mice and found no defect in exocytosis, but the residual expression of Munc18-3 could easily explain the absence of a phenotype (18). Here we achieved for the first time complete removal of Munc18-3 in platelets and show that this had no effect on exocytosis of dense, alpha, or lysosomal granules (Fig. 2).

Based on the above findings, we conclude that neither Munc18-1 nor Munc18-3 controls platelet regulated exocytosis. One limit to this conclusion is given by the resolution of our assays, but in mast cells, which also express the three Munc18 proteins, we could not detect any defect in cells lacking either Munc18-1 or Munc18-3. In that study we used a high-resolution assay that monitors individual granule-to-plasma membrane fusion events (17).

Two studies on platelets from five patients with FHL-5, all of them with biallelic mutations in the gene for Munc18-2, indicated that this protein plays an important role in platelet secretion (20, 39), but the need for human samples limited the number and type of experiments that could be performed. Munc18-2 global KO mice were designed to model this disease, but homozygosity was embryonically lethal (22, 24). Here we use a conditional KO line in which we achieved total removal of Munc18-2 form platelets. We observed an almost complete suppression of release of alpha and dense granules (Figs. 2, S1, and S2). These findings were confirmed by our stereology analysis, which showed that Munc18-2–deficient platelets contain a normal number of granules of normal size and that they undergo the expected shape changes upon stimulation but do not release their granules (Fig. 4).

The only previous study that addressed the contribution of Munc18-2 to lysosomal granule release used platelets form two patients with FHL-5 and found only a partial exocytic defect (20), raising the possibility that another Munc18 paralog was involved in this process. In contrast, in our assays of lysosomal granule exocytosis we observed a signal that was barely above baseline in Munc18-2Δ/Δ platelets and no defect in the secretion of lysosomal contents in platelets from Munc18-1Δ/Δ and Munc18-3Δ/Δ mice (Figs. 2, 3, and S2). Thus, in the absence of Munc18-2, the failure in platelet regulated exocytosis is universal.

Based on evidence indicating that the release of each type of platelet granule is differentially regulated (40–42), we postulated that different molecular components could mediate exocytosis of each type of granule. We reported previously that Munc13–4 regulates dense granule release. The impaired secretion of ADP from dense granules in Munc13–4–deficient platelets indirectly affects the exocytosis of their alpha granules. This was proven when we were able to rescue alpha granule release with exogenous ADP in platelets lacking Munc13–4 (25). However, the severe exocytic defects observed in Munc18-2Δ/Δ platelets could not be rescued, even in the presence of high doses of collagen or thrombin, or by addition of ADP (Fig. 3). Consequently, these mutant platelets have an intrinsic defect in the exocytic machineries of all three types of granules. Therefore, although Munc13-4 could explain the differential release of granules from platelets, Munc18-2 cannot because it seems to be essential for all forms of platelet regulated exocytosis.

Previous studies on Munc18-2 in platelets lack functional assays. Platelets from Munc18-2Δ/Δ mice were unable to form aggregates at a low dose of collagen, but this defect was rescued when the dose of collagen was increased (Fig. 5). This has been reported in other platelets with defective exocytosis (25, 43, 44). One mechanism described previously is that in platelets exposed to high doses of collagen, αIIbβ3 already present on the plasma membrane is activated and mediates aggregation (45, 46).

To study platelet adhesion and aggregation, using a test that better simulates physiological conditions, we assessed the formation and stability of thrombi by subjecting whole blood to shear stress in a collagen-coated flow chamber. We chose a low and a high shear stress to simulate the parameters found under venous and arterial blood flow, respectively. We found that although Munc18-2–null platelets could bind to the layer of collagen, they failed to form thrombi in either of the conditions (Figs. 5 and S3).

Finally, using megakaryocyte-specific Munc18-2 conditional KO mice allowed us to study the consequences of lacking Munc18-2 exclusively in platelets without affecting other tissues with important roles in thrombosis and hemostasis. Although Munc18-2Δ/Δ mice had a normal number of circulating platelets (Table 1), they had severe impairments in arterial and venous hemostasis and did not form occlusive thrombi after chemically induced endothelial damage (Fig. 6).

Interestingly, we did not find any significant defect in platelet exocytosis or function in Munc18-2+/− mice. A study made on platelets from one heterozygote FHL-5 human showed a mild exocytic defect, suggesting that expression levels of Munc18-2 might have a rate-limiting factor in these processes (20). We found a dose-dependency between platelet Munc13-4 expression and release of dense granules, formation of thrombi in vitro and in vivo, and effectiveness of hemostasis (25), but we could not replicate any of these findings in the case of Munc18-2 using multiple animals (Figs. 2–6). Our results indicate that the presence of Munc18-2 is critical for all forms of platelet regulated exocytosis, but its expression is haplosufficient for these processes.

Experimental procedures

Mice

Munc18-1, -2, and -3 are encoded by the Stxbp1, -2, and -3 genes, respectively. Previously, we had created Munc18-2 (22) and Munc18-3 (17) conditional KO mice, and we obtained conditional KO mice for Munc18-1 (from Dr. M. Verhage, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) (21). In short, exon 2 of Stxbp1 and exon 1 of Stxbp2 and Stxbp3 were flanked with two loxP sites (floxed or F allele). Cre-mediated recombination of Stxbp1 exon 2 induces a frameshift that results in nonsense mutations and the absence of protein expression, whereas the recombination of exon 1 of Stxbp2 or Stxbp3 eliminates the start codon and expression in both cases.

We crossed Munc18-1F/F, Munc18-2F/F, and Munc18-3F/F with B6.C-Tg(CMV-cre)1Cgn/J mice (catalogue No. 006054, The Jackson Laboratory) to generate germline deletants (− allele). Because global deletion of any of the Munc18 proteins is lethal (17, 23, 24), we studied only global heterozygotes (+/−) for the three genes. We also generated megakaryocyte/platelet-specific KO mice (Munc18-1Δ/Δ, Munc18-2Δ/Δ, and Munc18-3Δ/Δ) by crossing Munc18-1F/F, Munc18-2F/F, and Munc18-3F/F with C57BL/6-Tg(Pf4-icre)Q3Rsko/J mice (catalogue No. 008535, The Jackson Laboratory).

All lines were on a C57BL/6J background. All experiments were carried out using mice of both sexes and protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and the Baylor College of Medicine.

Sample isolation

Under anesthesia with isoflurane, blood was collected into a citrated syringe (50 μl of 4% sodium citrate; 21-gauge needle) by inferior vena cava puncture. This sample was mixed with an equal volume of Tyrode's buffer (in mm: 5.56 glucose, 140 NaCl, 12 NaHCO3, 2.7 KCl, 0.46 NaH2PO4) and used as whole blood or centrifuged (relative centrifugal force, 60; 10 min) to isolate platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Washed platelets were obtained by centrifuging PRP (relative centrifugal force, 635; 10 min), washing the pellet with PBS, and resuspending it in Tyrode's buffer (2.5 × 108 platelets/ml). Cell counts were obtained from whole blood and washed platelets with a scil VET abc hematology analyzer (Scil, Henry Schein Animal Health) and a Z2 counter (Beckman Coulter), respectively.

Expression studies

For RT-qPCR, the washed platelets were lysed (DNA/RNA Shield, Zymo Research), and total RNA was isolated (E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I, Omega Bio-tek), concentrated and cleaned (RNA Clean & Concentrator, Zymo Research), and reverse-transcribed (qScript cDNA SuperMix, Quanta Biosciences). cDNA was amplified (PerfeCTa qPCR ToughMix, Quanta Biosciences), and the abundance of Munc18-1 (Mm00436837_m1), Munc18-2 (Mm00441589_m1), Munc18-3 (Mm00441605_m1), and β-actin (Mm00607939_s1) transcripts was relatively quantified using hydrolysis probes (TaqMan gene expression assays, Life Technologies) on a ViiA7 RT-PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For immunoblotting, the tissue and platelet lysates were run under denaturing conditions on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with anti–Munc18-1 (1:4000; M2694), anti–Munc18-2 (1:200; HPA015564), anti–Munc18-3 (1:5000; M7695; all from Sigma-Aldrich), and anti–β-actin (1:20000; ab119716; Abcam) antibodies.

Secretion assays

ATP release was assessed by stirring (1200 rpm, 37 °C, 5 min; model 700 Lumi-Aggregometer) whole blood (600 μl diluted 5-fold in Tyrode's buffer) in the presence of luciferin/luciferase and collagen or thrombin (all from Chrono-Log Corp.). For PF4 release, 5 × 107 washed platelets were stimulated for 5 min with thrombin or for 7 min with collagen, with or without ADP in the presence of 0.7 mm CaCl2, and pelleted, and PF4 in the supernatants was measured by ELISA (ELM-PF4. RayBiotech). For P-selectin and LAMP-1 translocation, 2.5 × 106 washed platelets were incubated in 40 μl of PBS with FITC–anti-P-selectin (10 μg/ml, 10 min; RB40.34, BD Pharmingen) or FITC–anti-LAMP-1 (10 μg/ml, 10 min; 1D4B, BD Pharmingen) antibodies. The platelets were then stimulated with thrombin for 10 min in the presence of 0.7 mm CaCl2. Finally, samples were placed on ice, diluted with 1 ml of PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry (LSR II, BD Biosciences). The difference between the baseline and stimulated values of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) represents the gain in MFI (ΔMFI).

EM and stereology

Resting and activated (0.1 unit/ml thrombin, 0.7 mm CaCl2, 2 min) washed platelets were fixed in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde (2 h), post-fixed in aqueous 1% OsO4 (1 h, both at room temperature), pelleted, and embedded in 3% low-melting agarose. The agarose blocks were dehydrated through an acetone series before embedding in EMbed 812 resin (25). Sections (100 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate prior to acquiring images with a FEI Tecnai 12 transmission electron microscope (8200×, 100 KeV). For stereology, 10 fields/sample (∼20 platelet profiles/field) were analyzed in STEPanizer (47) with a grid consisting of 81 horizontal line pairs (line width = 2 pixels (0.0318 μm), T-bar = 5 pixels (0.0795 μm)). We obtained the volume occupied by platelet granules in regard to total platelet volume (volume density) and the granular surface area relative to total granule volume (surface density) using a point-count and a line intercept-count systems (25, 48, 49).

Aggregometry and flow-chamber assay

For aggregometry, the PRP (500 μl) was stirred (800 rpm, 37 °C, 10 min; model 700 Lumi-Aggregometer) in the presence of 0.7 mm CaCl2 and collagen, and light transmission was recorded over time. For the flow-chamber assays, whole blood was anticoagulated with 80 μm PPACK (d-phenylalanyl-prolyl-arginine chloromethyl ketone) and labeled with 10 μm mepacrine (37 °C, 20 min) before being perfused over collagen-coated (25 μg/ml; Helena Laboratories) plates at fixed shear stress in a microfluidic BioFlux system (Fluxion Biosciences). Thrombus buildup, monitored with a fluorescence microscope every 10 s for 200 s, was analyzed using a BioFlux Montage (50). The final thrombus size was used for statistical comparisons.

Bleeding time tests

We used mice (20 ± 2 weeks old, 30 ± 3 g) anesthetized with Avertin (tribromoethanol in tert-amyl alcohol, 0.4 mg/g intraperitoneally). We tested arterial hemostasis by transecting the tail 5 mm from the tip and venous hemostasis by sectioning only the dorsal tail venous plexus. The device reproducibly makes a transversal dorsal tail incision of 0.8 mm in depth at a point where the tail has a diameter of 3.8 mm (25). In both cases, the tails were immediately immersed in 37 °C saline, and the time to cessation of bleeding was recorded. All animals were euthanized after bleeding stopped or at 20 min. All bleeding that did not cease was assigned a value of 20 min for statistical analysis.

Ferric chloride-induced thrombosis

In mice (13 ± 1 week old) anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg intraperitoneally), a common carotid artery was exposed, and a 1 × 2–mm piece of filter paper soaked with 10% FeCl3 was applied to its surface for 3 min. After removing the filter paper and rinsing with saline, the time to cessation of blood flow sustained for at least 1 min was recorded using a Doppler flow probe (Transonic Systems). All animals were euthanized after vessel occlusion or at 30 min. All vessels that failed to occlude were assigned a value of 30 min for statistical comparisons.

Statistical analysis

All our variables were continuous. We tested first for normality with D'Agostino's K2 test. For normal data we first compared the means of all groups using analysis of variance, and if a significant difference was found we applied Tukey's HSD test for multiple pair-wise comparisons and Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons against the control group. For non-normal data we first compared all groups using the Kruskal–Wallis H test and followed any significant result with Dunn's test for multiple comparisons. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Author contributions

E. I. C. and R. A. C. data curation; E. I. C. and R. A. C. formal analysis; E. I. C. validation; E. I. C., R. G., K. B., Q. D., B. A. G., M. A. R., A. R. B., and R. E. R. investigation; E. I. C. visualization; E. I. C., R. G., K. B., Q. D., B. A. G., M. A. R., A. R. B., and R. E. R. methodology; E. I. C. writing-original draft; E. I. C. and R. A. writing-review and editing; A. R. B. software; A. R. B., R. E. R., and R. A. supervision; R. E. R. and R. A. resources; R. A. conceptualization; R. A. funding acquisition; R. A. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret M. Gondo (University of Houston) for assistance with the electron microscope and Kimberly Langlois and Ngoc-Anh Bui-Thanh (Baylor College of Medicine) for assistance with the in vivo thrombosis assay.

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI093533A, AI137319, and CA016672 (to R. A.), HL116524 (to R. E. R.), and EY007551 (to A. R. B.). This project was also supported by Merit Review Award I01 BX002551 (to R. E. R.) from the U. S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States government.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3 and Table S1.

- SNARE

- soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor

- FHL-5

- familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5

- KO

- knockout

- LAMP

- lysosomal-associated membrane protein

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity

- Munc

- mammalian homolog of C. elegans uncoordinated gene

- PF4

- platelet factor 4

- PRP

- platelet-rich plasma

- Stx

- syntaxin

- Stxbp

- Stx-binding protein

- VAMP

- vesicle-associated membrane protein

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR.

References

- 1. Blair P., and Flaumenhaft R. (2009) Platelet α-granules: Basic biology and clinical correlates. Blood Rev. 23, 177–189 10.1016/j.blre.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Daniel J. L., Dangelmaier C., Jin J., Ashby B., Smith J. B., and Kunapuli S. P. (1998) Molecular basis for ADP-induced platelet activation. I. Evidence for three distinct ADP receptors on human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2024–2029 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ciferri S., Emiliani C., Guglielmini G., Orlacchio A., Nenci G. G., and Gresele P. (2000) Platelets release their lysosomal content in vivo in humans upon activation. Thromb. Haemost. 83, 157–164 10.1055/s-0037-1613772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen Y. A., and Scheller R. H. (2001) SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 98–106 10.1038/35052017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin R. C., and Scheller R. H. (1997) Structural organization of the synaptic exocytosis core complex. Neuron 19, 1087–1094 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80399-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Südhof T. C., and Rothman J. E. (2009) Membrane fusion: Grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science 323, 474–477 10.1126/science.1161748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dulubova I., Sugita S., Hill S., Hosaka M., Fernandez I., Südhof T. C., and Rizo J. (1999) A conformational switch in syntaxin during exocytosis: Role of munc18. EMBO J. 18, 4372–4382 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ma C., Li W., Xu Y., and Rizo J. (2011) Munc13 mediates the transition from the closed syntaxin-Munc18 complex to the SNARE complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 542–549 10.1038/nsmb.2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lai Y., Choi U. B., Leitz J., Rhee H. J., Lee C., Altas B., Zhao M., Pfuetzner R. A., Wang A. L., Brose N., Rhee J., and Brunger A. T. (2017) Molecular mechanisms of synaptic vesicle priming by Munc13 and Munc18. Neuron 95, 591–607 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rathore S. S., Bend E. G., Yu H., Hammarlund M., Jorgensen E. M., and Shen J. (2010) Syntaxin N-terminal peptide motif is an initiation factor for the assembly of the SNARE-Sec1/Munc18 membrane fusion complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22399–22406 10.1073/pnas.1012997108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shen J., Tareste D. C., Paumet F., Rothman J. E., and Melia T. J. (2007) Selective activation of cognate SNAREpins by Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Cell 128, 183–195 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shen C., Rathore S. S., Yu H., Gulbranson D. R., Hua R., Zhang C., Schoppa N. E., and Shen J. (2015) The trans-SNARE-regulating function of Munc18-1 is essential to synaptic exocytosis. Nat. Commun. 6, 8852 10.1038/ncomms9852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Houng A., Polgar J., and Reed G. L. (2003) Munc18-syntaxin complexes and exocytosis in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19627–19633 10.1074/jbc.M212465200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schraw T. D., Lemons P. P., Dean W. L., and Whiteheart S. W. (2003) A role for Sec1/Munc18 proteins in platelet exocytosis. Biochem. J. 374, 207–217 10.1042/bj20030610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reed G. L., Houng A. K., and Fitzgerald M. L. (1999) Human platelets contain SNARE proteins and a Sec1p homologue that interacts with syntaxin 4 and is phosphorylated after thrombin activation: Implications for platelet secretion. Blood 93, 2617–2626 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanda H., Tamori Y., Shinoda H., Yoshikawa M., Sakaue M., Udagawa J., Otani H., Tashiro F., Miyazaki J., and Kasuga M. (2005) Adipocytes from Munc18c-null mice show increased sensitivity to insulin-stimulated GLUT4 externalization. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 291–301 10.1172/JCI22681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gutierrez B. A., Chavez M. A., Rodarte A. I., Ramos M. A., Dominguez A., Petrova Y., Davalos A. J., Costa R. M., Elizondo R., Tuvim M. J., Dickey B. F., Burns A. R., Heidelberger R., and Adachi R. (2018) Munc18-2, but not Munc18-1 or Munc18-3, controls compound and single-vesicle-regulated exocytosis in mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 7148–7159 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schraw T. D., Crawford G. L., Ren Q., Choi W., Thurmond D. C., Pessin J., and Whiteheart S. W. (2004) Platelets from Munc18c heterozygous mice exhibit normal stimulus-induced release. Thromb. Haemost. 92, 829–837 10.1160/TH04-04-0263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pagel J., Beutel K., Lehmberg K., Koch F., Maul-Pavicic A., Rohlfs A. K., Al-Jefri A., Beier R., Bomme Ousager L., Ehlert K., Gross-Wieltsch U., Jorch N., Kremens B., Pekrun A., Sparber-Sauer M., et al. (2012) Distinct mutations in STXBP2 are associated with variable clinical presentations in patients with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 (FHL5). Blood 119, 6016–6024 10.1182/blood-2011-12-398958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Al Hawas R., Ren Q., Ye S., Karim Z. A., Filipovich A. H., and Whiteheart S. W. (2012) Munc18b/STXBP2 is required for platelet secretion. Blood 120, 2493–2500 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heeroma J. H., Roelandse M., Wierda K., van Aerde K. I., Toonen R. F., Hensbroek R. A., Brussaard A., Matus A., and Verhage M. (2004) Trophic support delays but does not prevent cell-intrinsic degeneration of neurons deficient for munc18–1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 623–634 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jaramillo A. M., Piccotti L., Velasco W. V., Huerta Delgado A. S., Azzegagh Z., Chung F., Nazeer U., Farooq J., Brenner J., Parker-Thornburg J., Scott B. L., Evans C. M., Adachi R., Burns A. R., Kreda S. M., et al. (2019) Different Munc18 proteins mediate baseline and stimulated airway mucin secretion. JCI Insight 10.1172/jci.insight.124815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verhage M., Maia A. S., Plomp J. J., Brussaard A. B., Heeroma J. H., Vermeer H., Toonen R. F., Hammer R. E., van den Berg T. K., Missler M., Geuze H. J., and Südhof T. C. (2000) Synaptic assembly of the brain in the absence of neurotransmitter secretion. Science 287, 864–869 10.1126/science.287.5454.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim K., Petrova Y. M., Scott B. L., Nigam R., Agrawal A., Evans C. M., Azzegagh Z., Gomez A., Rodarte E. M., Olkkonen V. M., Bagirzadeh R., Piccotti L., Ren B., Yoon J. H., McNew J. A., et al. (2012) Munc18b is an essential gene in mice whose expression is limiting for secretion by airway epithelial and mast cells. Biochem. J. 446, 383–394 10.1042/BJ20120057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cardenas E. I., Breaux K., Da Q., Flores J. R., Ramos M. A., Tuvim M. J., Burns A. R., Rumbaut R. E., and Adachi R. (2018) Platelet Munc13–4 regulates hemostasis, thrombosis and airway inflammation. Haematologica 103, 1235–1244 10.3324/haematol.2017.185637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schneider J. P., and Ochs M. (2013) Stereology of the lung. Methods Cell Biol. 113, 257–294 10.1016/B978-0-12-407239-8.00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rodarte E. M., Ramos M. A., Davalos A. J., Moreira D. C., Moreno D. S., Cardenas E. I., Rodarte A. I., Petrova Y., Molina S., Rendon L. E., Sanchez E., Breaux K., Tortoriello A., Manllo J., Gonzalez E. A., et al. (2018) Munc13 proteins control regulated exocytosis in mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 345–358 10.1074/jbc.M117.816884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kurz K. D., Main B. W., and Sandusky G. E. (1990) Rat model of arterial thrombosis induced by ferric chloride. Thromb. Res. 60, 269–280 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90106-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Voets T., Toonen R. F., Brian E. C., de Wit H., Moser T., Rettig J., Südhof T. C., Neher E., and Verhage M. (2001) Munc18-1 promotes large dense-core vesicle docking. Neuron 31, 581–591 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00391-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oh E., Kalwat M. A., Kim M. J., Verhage M., and Thurmond D. C. (2012) Munc18-1 regulates first-phase insulin release by promoting granule docking to multiple syntaxin isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25821–25833 10.1074/jbc.M112.361501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bin N. R., Jung C. H., Piggott C., and Sugita S. (2013) Crucial role of the hydrophobic pocket region of Munc18 protein in mast cell degranulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 4610–4615 10.1073/pnas.1214887110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adhikari P., and Xu H. (2018) PKC-dependent phosphorylation of Munc18a at Ser313 in activated RBL-2H3 cells. Inflamm. Res. 67, 1–3; Correction (2018) Inflamm. Res. 67, 553 10.1007/s00011-018-1169-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhu D., Xie L., Karimian N., Liang T., Kang Y., Huang Y. C., and Gaisano H. Y. (2015) Munc18c mediates exocytosis of pre-docked and newcomer insulin granules underlying biphasic glucose stimulated insulin secretion in human pancreatic β-cells. Mol. Metab. 4, 418–426 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khan A. H., Thurmond D. C., Yang C., Ceresa B. P., Sigmund C. D., and Pessin J. E. (2001) Munc18c regulates insulin-stimulated glut4 translocation to the transverse tubules in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4063–4069 10.1074/jbc.M007419200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brochetta C., Vita F., Tiwari N., Scandiuzzi L., Soranzo M. R., Guérin-Marchand C., Zabucchi G., and Blank U. (2008) Involvement of Munc18 isoforms in the regulation of granule exocytosis in neutrophils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 1781–1791 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen D., Lemons P. P., Schraw T., and Whiteheart S. W. (2000) Molecular mechanisms of platelet exocytosis: Role of SNAP-23 and syntaxin 2 and 4 in lysosome release. Blood 96, 1782–1788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lemons P. P., Chen D., and Whiteheart S. W. (2000) Molecular mechanisms of platelet exocytosis: Requirements for α-granule release. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 267, 875–880 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Flaumenhaft R., Croce K., Chen E., Furie B., and Furie B. C. (1999) Proteins of the exocytotic core complex mediate platelet α-granule secretion: Roles of vesicle-associated membrane protein, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 4. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2492–2501 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sandrock K., Nakamura L., Vraetz T., Beutel K., Ehl S., and Zieger B. (2010) Platelet secretion defect in patients with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 (FHL-5). Blood 116, 6148–6150 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jonnalagadda D., Izu L. T., and Whiteheart S. W. (2012) Platelet secretion is kinetically heterogeneous in an agonist-responsive manner. Blood 120, 5209–5216 10.1182/blood-2012-07-445080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Flaumenhaft R., Dilks J. R., Rozenvayn N., Monahan-Earley R. A., Feng D., and Dvorak A. M. (2005) The actin cytoskeleton differentially regulates platelet α-granule and dense-granule secretion. Blood 105, 3879–3887 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Italiano J. E. Jr, Richardson J. L., Patel-Hett S., Battinelli E., Zaslavsky A., Short S., Ryeom S., Folkman J., and Klement G. L. (2008) Angiogenesis is regulated by a novel mechanism: Pro- and antiangiogenic proteins are organized into separate platelet α granules and differentially released. Blood 111, 1227–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Graham G. J., Ren Q., Dilks J. R., Blair P., Whiteheart S. W., and Flaumenhaft R. (2009) Endobrevin/VAMP-8-dependent dense granule release mediates thrombus formation in vivo. Blood 114, 1083–1090 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ren Q., Wimmer C., Chicka M. C., Ye S., Ren Y., Hughson F. M., and Whiteheart S. W. (2010) Munc13–4 is a limiting factor in the pathway required for platelet granule release and hemostasis. Blood 116, 869–877 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jarvis G. E., Best D., and Watson S. P. (2004) Differential roles of integrins α2β1 and αIIbβ3 in collagen and CRP-induced platelet activation. Platelets 15, 303–313 10.1080/09537100410001710254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cho M. J., Liu J., Pestina T. I., Steward S. A., Thomas D. W., Coffman T. M., Wang D., Jackson C. W., and Gartner T. K. (2003) The roles of αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signal transduction, thromboxane A2, and adenosine diphosphate in collagen-induced platelet aggregation. Blood 101, 2646–2651 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tschanz S. A., Burri P. H., and Weibel E. R. (2011) A simple tool for stereological assessment of digital images: The STEPanizer. J. Microsc. 243, 47–59 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2010.03481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Melicoff E., Sansores-Garcia L., Gomez A., Moreira D. C., Datta P., Thakur P., Petrova Y., Siddiqi T., Murthy J. N., Dickey B. F., Heidelberger R., and Adachi R. (2009) Synaptotagmin-2 controls regulated exocytosis but not other secretory responses of mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19445–19451 10.1074/jbc.M109.002550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thakurdas S. M., Melicoff E., Sansores-Garcia L., Moreira D. C., Petrova Y., Stevens R. L., and Adachi R. (2007) The mast cell-restricted tryptase mMCP-6 has a critical immunoprotective role in bacterial infections. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20809–20815 10.1074/jbc.M611842200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Da Q., Teruya M., Guchhait P., Teruya J., Olson J. S., and Cruz M. A. (2015) Free hemoglobin increases von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet adhesion in vitro: Implications for circulatory devices. Blood 126, 2338–2341 10.1182/blood-2015-05-648030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.