ABSTRACT

Background: With the release of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) has been updated to meet the revisions of the diagnostic criteria for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). However, the diagnostic utility and reliability of a Brazilian version of the new Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) have not been investigated yet.

Objective: To investigate the internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and diagnostic utility of the complete version (21-item) and two abbreviated (8-item and 4-item) versions of the Brazilian PCL-5.

Methods: A total of 85 individuals with a history of exposure to at least one traumatic event underwent a diagnostic interview using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5-CV) and completed the Brazilian version of the PCL-5. Moreover, participants were invited to complete the checklist for a second time 10–30 days after the first assessment.

Results: Both the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5 showed good internal consistency (complete PCL-5, α = .96; 8-item, α = .93; 4-item, α = .85) and test-retest reliability (complete PCL-5, ICC .87 [95% CI, 0.65–0.95]; 8-item, ICC .84 [95% CI, 0.60–0.94]; 4-item, ICC .84 [95% CI, 0.58–0.94]). Diagnostic utility analyses using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5-CV) revealed that a cutoff point of 36 presented the higher overall efficiency for predicting a PTSD diagnosis Overall Efficiency (OE, .80) and corresponded to Youden’s index J (.65). For the 8-item version, a cutoff point of 13 corresponded to Youden’s index J (.61), while scores of 21 or more were associated with the highest OE (.78). For the 4-item PCL-5, scores > 7 presented the highest OE (.77) and corresponded to Youden’s index J (.59).

Conclusions: Overall, the findings provide relevant evidence regarding the high reliability and diagnostic utility of this Brazilian version of the PCL-5.

KEYWORDS: PTSD, DSM-5, psychometrics, Brazil, Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders

HIGHLIGHTS

• PCL-5 complete/abbreviated versions demonstrated good internal consistency and test-retest reliability. • Cutoff point > 35 presented the higher overall efficiency for predicting PTSD diagnosis. • For the 8-item version the cutoff point > 12 is suggested for screening PTSD. • For the 4-item PCL-5, a score > 7 presented the higher overall efficiency (.77). • PCL-5 and its abbreviated versions are adequate for research use among Brazilian samples.

Abstract

Antecedentes: con la publicación de la quinta edición del Manual de Diagnóstico y Estadístico para los Trastornos Mentales (DSM-5), el Cuestionario para el Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (PCL) se ha actualizado para cumplir con las revisiones de los criterios de diagnósticos del trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT). Sin embargo, la utilidad diagnóstica y la confiabilidad de una versión brasileña del nuevo cuestionario de trastorno de estrés postraumático (PCL-5) aún no se ha investigado.

Objetivo: investigar la consistencia interna, la confiabilidad test-retest y la utilidad diagnóstica de la versión completa (21 ítems) y dos versiones abreviadas (8 y 4 ítems) del PCL-5 brasileño.

Métodos: Un total de 85 individuos con antecedentes de exposición, al menos, a un evento traumático se sometieron a una entrevista diagnóstica utilizando la entrevista clínica estructurada para el DSM-5 (SCID-5-CV) y completaron la versión brasileña del PCL-5. Además, los participantes fueron invitados a completar el cuestionario por segunda vez entre 10 y 30 días después de la primera evaluación.

Resultados: Tanto la versión completa como las abreviadas de la PCL-5 brasileña mostraron una buena consistencia interna (PCL-5 completa, α = .96; 8 ítem, α = .93; 4-item, α = .85) y confiabilidad test-retest (PCL-5 completa, ICC .87 [IC 95%, .65 - .95]; 8 ítems, ICC .84 [IC 95%, 0.60 - 0.94]; 4 ítems, ICC .84 [IC 95%, 0.58] - 0,94]). Los análisis de utilidad diagnóstica que utilizaron el SCID-5-CV revelaron que un punto de corte de 36 presentó la mayor eficiencia general para predecir un diagnóstico de TEPT (OE, .80) y correspondió al índice J de Youden (.65). Para la versión de 8 ítems, un punto de corte de 13 correspondió al índice J de Youden (.61), mientras que las puntuaciones de 21 o más se asociaron con el OE más alto (.78). Para el PCL-5 de 4 ítems, los puntajes> 7 presentaron el OE más alto (.77) y correspondieron al índice J de Youden (.59).

Conclusiones: En conjunto, los hallazgos proporcionan evidencia relevante con respecto a la alta confiabilidad y utilidad diagnóstica de esta versión brasileña del PCL-5.

PALABRAS CLAVES: TEPT, DSM-5, Psicométricas, Brasil

Abstract

背景:随着第五版精神障碍诊断和统计手册(DSM-5)的发布,创伤后应激障碍检查表( PCL)已更新,以更新创伤后应激障碍(PTSD)诊断标准的修订。然而,巴西语版本的新创伤后应激障碍检查表(PCL-5)的诊断效用和可靠性尚未得到研究。

目的:研究巴西PCL-5完整版(21题目)和两个简版(分别有8个题目和4个题目)的内部一致性、重测信度和诊断效用。

方法:使用DSM-5的结构化临床访谈(SCID-5-CV)对85名有至少一次创伤事件暴露史的个体进行诊断性访谈,并完成巴西版PCL-5。另外,邀请被试在第一次测量后的10-30天内第二次填写检查表。

结果:巴西PCL-5的完整版和简版均显示出良好的内部一致性(完整版,α = .96; 8题,α = .93; 4题,α = .85)和重测信度(完整版,ICC .87 [95%CI,.65 - .95]; 8题,ICC .84 [95%CI,0.60 - 0.94]; 4题,ICC .84 [95%CI,0.58 - 0.94])。使用SCID-5-CV的诊断效用分析显示,划界分36表现出预测PTSD诊断的总体效率较高(OE,.80),与Youden指数J(.65)相对应。对于8题目版本,划界分13对应于Youden的指数J(.61),而21或更高的得分与最高的OE(.78)相关联。对于4题目PCL-5,得分> 7表示最高的OE(.77)并且对应于Youden的指数J(.59)。

结论:总体而言,该研究结果提供了有关该巴西版PCL-5的高可靠性和诊断效用的相关证据。

关键词: 创伤后应激障碍, DSM-5, 心理测量, 巴西

1. Introduction

Since its development in 1990, the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) has been widely used as a preferred self-report measure of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). With the release of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), the PCL has been updated to meet the revisions of the diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Weathers et al., 2013). Significant changes in the instrument include the insertion of PTSD in a new chapter on Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders; the proposal of four distinct diagnostic clusters instead of three (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and arousal); and the inclusion of three additional symptoms, increasing the total number of symptoms from 17 to 20 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The new Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) has 20 items designed to screen for PTSD symptoms as described by the DSM-5. For each of the 20 items, respondents should indicate how much they have been bothered by the symptom in the past month using a 5-point scale (0–4) ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’. The instrument can be administered in three ways, as follows: (a) without Criterion A; (b) with a brief assessment of Criterion A; and (c) with the revised Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) and extended Criterion A assessment. The 20 items of the PCL-5 are summed to obtain a total symptom severity score ranging from 0 to 80. DSM-5 symptom cluster severity scores can also be calculated by summing the scores for the items within a given cluster (Cluster B – items 1 to 5; Cluster C – items 6 to 7; Cluster D – items 8 to 14; Cluster E – items 15 to 20). A provisional PTSD diagnosis can be obtained by considering items rated as 2 (moderate) or higher as a symptom endorsed, then following the DSM-5 diagnostic rule (at least one B, one C, two D, and two E symptoms present; Weathers et al., 2013).

Previous investigations on the psychometric properties of the PCL-5 in other cultures have demonstrated excellent psychometric validity and reliability of the instrument (Ashbaugh, Houle-Johnson, Herbert, El-Hage, & Brunet, 2016; Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015; Bovin et al., 2016; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017; Sveen, Bondjers, & Willebrand, 2016; Verhey, Chibanda, Gibson, Brakarsh, & Seedat, 2018; Wortmann et al., 2016). Preliminary findings on cutoff scores have presented mixed results, with suggested cutoff points ranging from 31 to 38 (Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Blevins et al., 2015; Bovin et al., 2016; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017). With regard to the abbreviated versions of the PCL-5, a previous study found evidence for the usefulness of two short forms of the checklist (4-item and 8-item) for PTSD screening (Price, Szafranski, van Stolk-Cooke, & Gros, 2016). However, to our knowledge, there are no studies assessing the diagnostic utility and reliability of a Brazilian version of the PCL-5.

Our objective was to assess the psychometric properties of a Brazilian version of the PCL-5 (Osorio et al., 2017) including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and the diagnostic utility of the complete (20-item) and abbreviated (4-item and 8-item) versions of the Brazilian PCL-5.

2. Methods

2.1. Measures

The Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders module of the SCID-5-CV (First & Williams, 2016) was applied to all participants by trained psychiatrists and clinical psychologists with at least two years of experience (mean = 5.2; SD = 4.5; range = 2–18 years) to assess the presence of a PTSD diagnosis. The Brazilian version of the PCL-5 with the LEC-5 and extended Criterion A was also applied to all participants. The cross-cultural translation and adaptation procedures of the Brazilian PCL-5 have been described in detail in a previous publication (Osorio et al., 2017). Briefly, the procedure involved multiple translations, synthesis of versions, back translation reviewed by the original author, content validation by an expert committee, and face validation by the target population.

2.2. Participants and procedures

Participants were selected from the sample of a larger project aiming to assess the reliability of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the SCID-5-CV (First & Williams, 2016). Between March 2017 and August 2018, a total of 222 individuals were recruited in a psychiatric outpatient unit of a Brazilian tertiary hospital by mental health staff (n = 172) and through advertisement in different community settings (e.g. primary care units, universities, and social media) (n = 50). Inclusion criteria were age above 18 years at the time of enrolment and a history of at least one traumatic event among those described in the DSM-5 (Criterion A). A total of 52 individuals from the psychiatric outpatient unit and 33 from the general community met the inclusion criteria and were included in the present study (N = 85).

Of the 85 participants, 43 completed the PCL-5 after responding to the SCID-5-CV, and 42 completed the PCL-5 before completing the SCID-5-CV. Although other psychiatric diagnoses were assessed through the SCID-5-CV, the presence of comorbid conditions was not considered for the purposes of the study. All participants were blind in respect to their SCID-5-CV diagnosis. Similarly, the psychiatrists and clinical psychologists involved were blind in regard to the participants’ previous diagnoses and PCL-5 scores. As part of the larger project mentioned above (SCID-5-CV reliability study), 70% of the individuals were randomly selected to complete the SCID-5-CV a second time. Of these, 21 were included in the PCL-5 study and were therefore asked to also complete the PCL-5 for a second time (median test-retest time = 16 days; range = 10–30 days).All participants signed an informed consent form in accordance with the procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board (process no. HCRP – 2.019951).

2.3. Statistical analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive analysis

We used descriptive analyses (mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage) to characterize the study sample in terms of demographic characteristics, PTSD diagnosis, and traumatic event exposure. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation) and inter item correlations were calculated for all PCL-5 items.

2.3.2. Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5 was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha using version 21 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 21; IBM Corp., 2012). According to the literature, alpha values higher than .70 indicate acceptable internal consistency (Gliem & Gliem, 2003). Pearson correlation coefficients between each of the clusters of the PCL-5 were also calculated. The strength of the correlations was classified as follows: negligible (< .30), low (.30 to .50), moderate (.51 to .70), high (.71 to .90), and very high (> .90) (Mukaka, 2012).

2.3.3. Test-retest reliability

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to estimate the test-retest reliability of the Brazilian complete and abbreviated versions of the PCL-5. ICC estimates and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated using SPSS 21(IBM Corp, 2012) based on a mean of two measurements, absolute-agreement, 2-way mixed-effects model. Values lower than .5, between .5 and .75, between .75 and .90, and greater than .90 are indicative of poor, moderate, good, and excellent reliability, respectively (Koo & Li, 2016).

2.3.4. Diagnostic utility

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used to estimate how accurately the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5 could discriminate between positive and negative diagnoses of PTSD according to the SCID-5-CV (First & Williams, 2016). The following indices were used to estimate the diagnostic accuracy of different cutoff scores: area under the curve (AUC) with standard error (SE) and its binomial exact 95% confidence interval; Youden’s J index; sensitivity (Sn); specificity (Sp); positive (+LR) and negative (-LR) likelihood ratios (LR); positive (+PV) and negative (-PV) predictive values; and overall efficiency (OE). All diagnostic utility analyses were performed using the MedCalc statistical software for Windows, version 18.10 (MedCalc, 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

The sample included 55 women (64.7%) and 30 men (35.3%) aged between 18 and 75 years old (mean = 40.0; SD = 14.3). Participants were from different professional and educational fields and reported to have between 1 and 23 years of education (mean = 14.8; SD = 4.1). The most prevalent traumatic events experienced by participants were sexual violence (n = 30 [35.3%]), armed robbery (n = 16 [18.8%]), sudden violent or accidental death of a close person (n = 10 [11.8%]), car accident (n = 9 [10.6%]), kidnaping (n = 5 [5.9%]), and life-threatening illness (n = 5 [5.9%]).

The diagnostic evaluation with the SCID-5-CV revealed that 34 (40%) participants had a diagnosis of PTSD according to DSM-5 criteria. The mean total score of the Brazilian PCL-5 was 34.9 (SD = 2.5) for the complete PCL-5, 13.9 (SD = 1.1) for the 8-item abbreviated checklist, and 7.9 (SD = 0.6) for the 4-item abbreviated version of the PCL-5. The complete Brazilian version of the PCL-5 had very high correlations with its abbreviated versions containing eight (r = .97; p < .001) and four (r = .95; p < .001) items.

3.2. Descriptive statistics and inter item correlations

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation statistics for the items of the Brazilian version of the PCL-5.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for the Brazilian PCL-5 items.

| Item | Mean | SD | Range | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Item 12 | Item 13 | Item 14 | Item 15 | Item 16 | Item 17 | Item 18 | Item 19 | Item 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.86 | 1.47 | 0–4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 1.09 | 1.32 | 0–4 | .49** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 1.62 | 1.47 | 0–4 | .78** | .51** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 2.25 | 1.46 | 0–4 | .75** | .45** | .70** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 1.98 | 1.59 | 0–4 | .67** | .43** | .84** | .64** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | 2.06 | 1.56 | 0–4 | .67** | .41** | .70** | .67** | .71** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | 2.00 | 1.63 | 0–4 | .65** | .50** | .66** | .64** | .68** | .81** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 8 | 1.06 | 1.48 | 0–4 | .26* | .11 | .28* | .36** | .32** | .47** | .32** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | 2.11 | 1.60 | 0–4 | .54** | .55** | .59** | .68** | .56** | .51** | .56** | .27* | 1 | |||||||||||

| 10 | 1.75 | 1.61 | 0–4 | .51** | .54** | .59** | .64** | .57** | .53** | .51** | .21 | .70** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 11 | 2.18 | 1.60 | 0–4 | .69** | .58** | .71** | .78** | .71** | .64** | .67** | .26* | .75** | .758** | 1 | |||||||||

| 12 | 1.95 | 1.65 | 0–4 | .62** | .52** | .60** | .61** | .56** | .57** | .56** | .18 | .58** | .568** | .70** | 1 | ||||||||

| 13 | 1.52 | 1.53 | 0–4 | .64** | .54** | .60** | .64** | .65** | .58** | .53** | .33** | .63** | .641** | .73** | .67** | 1 | |||||||

| 14 | 1.39 | 1.47 | 0–4 | .59** | .41** | .49** | .62** | .50** | .53** | .50** | .34** | .58** | .596** | .58** | .55** | .75** | 1 | ||||||

| 15 | 1.51 | 1.56 | 0–4 | .52** | .54** | .63** | .53** | .68** | .50** | .60** | .18 | .62** | .559** | .69** | .60** | .61** | .50** | 1 | |||||

| 16 | 0.85 | 1.19 | 0–4 | .34** | .35** | .44** | .49** | .43** | .37** | .35** | .22* | .47** | .502** | .52** | .36** | .51** | .49** | .52** | 1 | ||||

| 17 | 2.15 | 1.62 | 0–4 | .56** | .54** | .58** | .65** | .56** | .51** | .57** | .16 | .68** | .639** | .68** | .65** | .54** | .49** | .54** | .30** | 1 | |||

| 18 | 1.98 | 1.59 | 0–4 | .60** | .58** | .65** | .70** | .67** | .50** | .52** | .18 | .67** | .598** | .74** | .68** | .61** | .45** | .56** | .31** | .84** | |||

| 19 | 1.92 | 1.58 | 0–4 | .65** | .50** | .75** | .67** | .68** | .65** | .64** | .40** | .64** | .607** | .77** | .68** | .66** | .59** | .52** | .54** | .56** | .61** | 1 | |

| 20 | 1.64 | 1.63 | 0–4 | .51** | .48** | .52** | .47** | .55** | .36** | .44** | .46** | .52** | .400** | .56** | .56** | .55** | .39** | .65** | .49** | .35** | .47** | .62** | 1 |

* Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed)

** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed)

3.3. Internal consistency

Both the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian of the PCL-5 showed satisfactory internal consistency for the total checklist score and for each of the four symptom clusters (Table 2).

Table 2.

Internal consistency analyses for the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5.

| Subscale | Complete PCL-5 | Abbreviated 8-item PCL-5 | Abbreviated 4-item PCL-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total PCL-5 | α = .96 (20 items) | α = .93 (8 items) | α = .85 (4 items) |

| Cluster B | α = .90 (5 items) | r = .75 (p < .001) | Not applicable |

| α = .86 (2 items) | |||

| Cluster C | α = .90 (2 items) | r = .81 (p < .001) | Not applicable |

| α = .90 (2 items) | |||

| Cluster D | α = .89 (7 items) | r = .58 (p < .001) | Not applicable |

| α = .73 (2 items) | |||

| Cluster E | α = .87 (6 items) | r = .61 (p < .001) | Not applicable |

| α = .76 (2 items) |

α = Cronbach’s alpha

r = Pearson correlation coefficient

Table 3 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between the different clusters of the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian version of the PCL-5. Significant moderate to very high positive correlations were found between all clusters for all versions of the Brazilian version of the PCL-5 (complete and 8-item and 4-item versions).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients between the different clusters of the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5.

| Correlation between clusters | Complete PCL-5 | Abbreviated 8-item PCL-5 | Abbreviated 4-item PCL-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| B and C | r = .79 (p < .001) | r = .74 (p < .001) | r = .65 (p < .001) |

| B and D | r = .84 (p < .001) | r = .73 (p < .001) | r = .57 (p < .001) |

| B and E | r = .86 (p < .001) | r = .78 (p < .001) | r = .60 (p < .001) |

| C and D | r = .72 (p < .001) | r = .65 (p < .001) | r = .56 (p < .001) |

| C and E | r = .68 (p < .001) | r = .68 (p < .001) | r = .52 (p < .001) |

| D and E | r = .88 (p < .001) | r = .84 (p < .001) | r = .67 (p < .001) |

3.4. Test-retest reliability

Of the 85 participants, 21 completed the test-retest phase of the study (17 women [81.0%] and four men [19.0%] aged between 23 and 70 [mean = 46, SD = 13.2]). The ICC based on a mean of two measurements, absolute-agreement, 2-way mixed-effects model indicated good test-retest reliability for both the complete Brazilian version of the PCL-5 (ICC = .87; 95% CI = 0.65–0.95) and its abbreviated versions of eight (ICC = .84; 95% CI = 0.60–0.94) and four (ICC = .84; 95% CI = 0.58–0.94) items.

3.5. Diagnostic utility

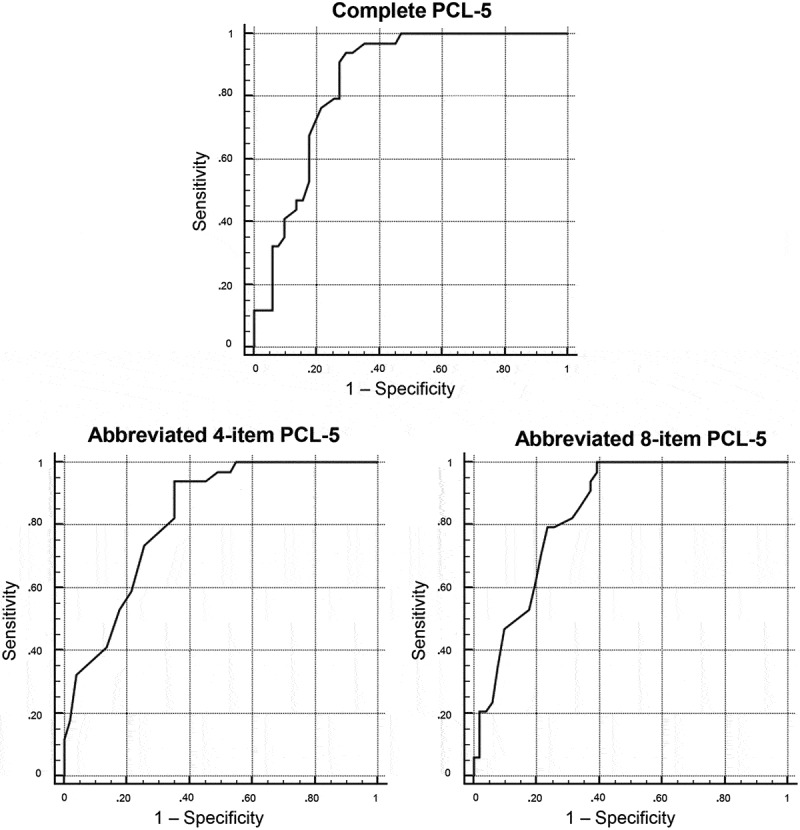

The area under the curve found in the ROC curve analysis was .85 (p < .0001), with a standard error of .42 and a 95% confidence interval between .75 and .92 for the complete version of the Brazilian PCL-5. For the 8-item version, the value was .84 (p < .0001), with a standard error of .42 and a 95% confidence interval between .74 and .91. Regarding the 4-item version, the area under the curve was .83 (p < .0001), with a standard error of .43, and a 95% confidence interval between .73 and .90. ROC curves for the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5 are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ROC curves of the completed and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5.

Sn, Sp, likelihoods, predictive values, and efficiency rates were also calculated for different cutoff points for both the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5. These data are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, likelihood, predictive, and overall efficiency values of the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5.

| PCL-5 Version/CP | Sn | Sp | +LR | -LR | +PV | -PV | OE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete PCL-5 | |||||||

| ≥ 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | .40 | - | .40 |

| 21 | 1 | .53 | 2.12 | 0 | .59 | 1 | .72 |

| 28 | .97 | .55 | 2.15 | .05 | .59 | .97 | .72 |

| 34 | .97 | .65 | 2.75 | .05 | .65 | .97 | .78 |

| 35 | .94 | .69 | 3.00 | .09 | .67 | .95 | .79 |

| 36a b | .94 | .71 | 3.20 | .08 | .68 | .95 | .80 |

| 37 | .91 | .73 | 3.32 | .12 | .69 | .93 | .80 |

| 41 | .79 | .73 | 2.89 | .28 | .66 | .84 | .75 |

| 42 | .79 | .75 | 3.12 | .28 | .68 | .84 | .77 |

| 43 | .76 | .78 | 3.55 | .30 | .70 | .83 | .78 |

| 45 | .68 | .82 | 3.83 | .39 | .72 | .79 | .77 |

| 49 | .53 | .82 | 3.00 | .57 | .67 | .72 | .71 |

| 50 | .47 | .84 | 3.00 | .63 | .67 | .71 | .69 |

| 51 | .47 | .86 | 3.43 | .61 | .70 | .71 | .71 |

| 52 | .44 | .86 | 3.21 | .65 | .68 | .70 | .69 |

| 54 | .41 | .90 | 4.20 | .65 | .74 | .70 | .71 |

| 55 | .35 | .90 | 3.60 | .72 | .71 | .68 | .68 |

| 57 | .32 | .92 | 4.12 | .73 | .73 | .67 | .68 |

| 59 | .32 | .94 | 5.50 | .72 | .79 | .68 | .69 |

| 66 | .12 | .94 | 2.00 | .94 | .57 | .62 | .61 |

| 72 | .12 | 1 | - | .88 | 1 | .63 | .65 |

| 80 | 0 | 1 | - | 1 | - | .60 | .60 |

| Abbreviated 8-item PCL-5 | |||||||

| ≥ 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | .40 | - | .40 |

| 13 a | 1 | .61 | 2.55 | 0 | .63 | 1 | .77 |

| 14 | .97 | .61 | 2.47 | .05 | .62 | .97 | .75 |

| 15 | .94 | .63 | 2.53 | .09 | .63 | .94 | .75 |

| 16 | .91 | .63 | 2.45 | .14 | .62 | .91 | .74 |

| 18 | .85 | .67 | 2.56 | .22 | .63 | .87 | .74 |

| 19 | .82 | .69 | 2.62 | .26 | .64 | .85 | .74 |

| 20 | .79 | .75 | 3.12 | .28 | .68 | .84 | .77 |

| 21 b | .79 | .76 | 3.37 | .27 | .69 | .85 | .78 |

| 22 | .71 | .78 | 3.27 | .38 | .69 | .80 | .75 |

| 23 | .62 | .80 | 3.15 | .48 | .68 | .76 | .73 |

| 24 | .53 | .82 | 3.00 | .57 | .67 | .72 | .71 |

| 25 | .47 | .90 | 4.80 | .59 | .76 | .72 | .73 |

| 26 | .35 | .92 | 4.50 | .70 | .75 | .68 | .69 |

| 27 | .24 | .94 | 4.00 | .81 | .73 | .65 | .66 |

| 28 | .21 | .96 | 5.25 | .83 | .78 | .65 | .66 |

| 29 | .21 | .98 | 1.50 | .81 | .88 | .65 | .67 |

| 31 | .06 | .98 | 3.00 | .96 | .67 | .61 | .61 |

| 32 | .06 | 1 | - | .94 | 1 | .61 | .62 |

| 33 | 0 | 1 | - | 1 | - | .60 | .60 |

| Abbreviated 4-item PCL-5 | |||||||

| ≥ 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | .40 | - | .40 |

| 4 | 1 | .45 | 1.82 | 0 | .55 | 1 | .67 |

| 5 | .97 | .47 | 1.83 | .06 | .55 | .96 | .67 |

| 6 | .97 | .51 | 1.98 | .06 | .57 | .96 | .69 |

| 7 | .94 | .55 | 2.09 | .11 | .58 | .93 | .71 |

| 8a b | .94 | .65 | 2.67 | .09 | .64 | .94 | .77 |

| 9 | .82 | .65 | 2.33 | .27 | .61 | .85 | .72 |

| 10 | .74 | .75 | 2.88 | .36 | .66 | .81 | .74 |

| 11 | .59 | .78 | 2.73 | .53 | .65 | .74 | .71 |

| 12 | .53 | .82 | 3.00 | .57 | .67 | .72 | .71 |

| 13 | .41 | .86 | 3.00 | .68 | .67 | .69 | .68 |

| 14 | .32 | .96 | 8.25 | .70 | .85 | .68 | .71 |

| 15 | .18 | .98 | 9.00 | .84 | .86 | .64 | .66 |

| 16 | .12 | 1 | - | .88 | 1 | .63 | .65 |

| 17 | 0 | 1 | - | 1 | - | .60 | .60 |

CP = cutoff point; Sn = sensitivity; Sp = specificity; +LR = positive likelihood ratio; -LR = negative likelihood ratio; +PV = positive predictive value; -PV = negative predictive value; OE = overall efficiency; a cutoff point correspondent to the Youden index J, b cutoff point with the highest overall efficiency

For the complete Brazilian version of the PCL-5, a cutoff point of 36 was the one that best equilibrated Sn, Sp, and predictive values (Youden index J = .65). This cutoff point was also the one with the highest OE value and is, therefore, the cutoff point suggested for use in Brazilian samples.

Regarding the 8-item Brazilian PCL-5, a cutoff point of 13 corresponded to Youden’s index J (.61), but was not the one associated with the highest OE for predicting a PTSD diagnosis. In contrast, a cutoff point of 21 presented the highest OE. Therefore, the cutoff point of 13 is suggested for the purpose of screening, while a cutoff point of 21 can be used as an optimal criterion when higher specificity is required.

For the 4-item Brazilian PCL-5, a cutoff point of 8 was the criterion value corresponding to Youden’s index J (.59) and also the one to present the highest OE value, being the cutoff point suggested for use in Brazilian samples.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate the psychometric reliability and diagnostic utility of a Brazilian version of the PCL-5. Our results showed the psychometric adequacy of both the complete and abbreviated versions of the checklist, suggesting that the instrument is adequate for use in Brazilian samples.

Regarding internal consistency, in line with previous studies in other cultures, the Brazilian PCL-5 has shown excellent Cronbach’s alpha values (Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Blevins et al., 2015; Bovin et al., 2016; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017; Price et al., 2016; Sveen et al., 2016; Verhey et al., 2018; Wortmann et al., 2016). The internal consistency of the independent clusters was also adequate, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .87 to .90. Additionally, moderate to very high positive significant correlations were verified between the four clusters of the PCL-5, which is compatible with the understanding that the different clusters of symptoms contribute to a single diagnosis (PTSD) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Similarly, in accordance with previous evidence, the present study identified good levels of test-retest reliability for this Brazilian version of the PCL-5 (Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Blevins et al., 2015; Bovin et al., 2016; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017; Sveen et al., 2016).

The cutoff point of 36 was the one to show the best equilibrium between Sn, Sp, and predictive values, and was also the one that presented the highest diagnostic efficiency for predicting a SCID-5-CV diagnosis of PTSD. Previous studies on discriminant validity have showed mixed results, with suggested cutoff points ranging from 31 to 38 (Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Blevins et al., 2015; Bovin et al., 2016; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017; Wortmann et al., 2016). These mixed results may be related to the presence of heterogeneity across the studies regarding their sample characteristics and choice of reference diagnostic measure. With regard to sample characteristics, most previous research was carried out with specific populations such as university students (Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Blevins et al., 2015), veterans (Bovin et al., 2016; Wortmann et al., 2016), and exclusively clinical samples (Bovin et al., 2016; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017; Wortmann et al., 2016). In contrast, our study included a sample from different clinical and community settings, as well as participants with different occupations and levels of education. In addition, different from previous studies that used signal-detection analysis (Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Blevins et al., 2015; Wortmann et al., 2016) or the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) (Bovin et al., 2016; Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017) as a reference diagnostic standard for PTSD, our study used the SCID-5-CV (First & Williams, 2016) to evaluate the presence of a PTSD diagnosis among the participants.

Considering the challenges associated with the use of lengthy instruments in large, multifaceted surveys, the present study also assessed the psychometric properties of two abbreviated (4-item and 8-item) versions of the PCL-5 suggested by a previous publication (Price et al., 2016). Similar to the results identified for the complete version of the Brazilian PCL-5, both the 4-item and 8-item versions have shown satisfactory levels of internal consistency and test-retest reliability. While the use of the full checklist is preferable in face of the large body of evidence showing the psychometric soundness of the PCL-5 in different cultures, these short versions of the checklist can be very useful for screening purposes in contexts where survey time constraints are imperative. Our results suggest that these items could be used to identify individuals who are likely to meet the criteria for PTSD in further evaluations.

With regard to diagnostic utility, the cutoff point of 8 was the one that best equilibrated Sn, Sp, and predictive values for the 4-item Brazilian PCL-5. This cutoff point presented a diagnostic accuracy even better than the ones identified by the previous study that suggested the use of this abbreviated measure (Price et al., 2016). For the 8-item Brazilian PCL-5, the cutoff point of 13 was the one corresponding to Youden’s index J, while the cutoff of 21 was the one that presented the highest overall efficiency. Therefore, we suggest the cutoff of 13 for contexts with strictly screening purposes, and the cutoff of 21 for contexts where higher specificity may be required. Similarly to the results for the 4-item PCL-5, both the cutoff points of 13 and 21 presented even better diagnostic accuracy for predicting a PTSD diagnosis than the values identified by the previous study proposing the use of this 8-item abbreviated checklist (Price et al., 2016).

Noteworthy, when comparing the cutoff points suggested for the abbreviated checklists with the full PCL-5, the 4-item version presented the same Sn as the full checklist (.94) and a small reduction in Sp (.71 vs .65). On the other hand, the 8-item PCL-5 presented a large reduction in Sn (.94 vs .76) with a small improvement in Sp (.71 vs .76). Therefore, the 4-item PCL-5 is likely to be a better choice than the 8-item version when the use of abbreviated instruments is necessary.

The current study has numerous strengths, including the utilization of a structured clinical interview (SCID-5-CV) as a reference diagnostic standard for PTSD; the assessment of internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and diagnostic utility with suggestions of optimal cutoff points for the Brazilian PCL-5; and the assessment of these properties in both the complete and abbreviated versions of the checklist. Importantly, our results should be interpreted with the limitations of the study in mind. First, while there is no conclusive evidence about sample size effects on Cronbach’s alpha values (Bonett, 2002; Peterson, 1994), it is possible that the small sample size in the present study introduced overestimation biases to our internal consistency and diagnostic accuracy results (Leeflang, Moons, Reitsma & Zwinderman1, 2008). Also, due to sample size limitations we were not able to carry out a confirmatory factor analysis for the Brazilian PCL-5 and to compare cutoff scores for clinical and non-clinical samples. Second, rather than applying different versions of the PCL-5, we only applied the full PCL-5 to the participants and then picked out the items for each abbreviated checklist based on the results from a previous study (Price et al., 2016). Although the application of this methodology is common in the assessment of abbreviated scales (Thimm, Jordan, & Bach, 2016), it is possible that participants’ replies to the 4-item and 8-item versions of the PCL-5 have been influenced by the completion of the full checklist. Third, the assessment of a convenience sample from a single medium-sized (682,302 people) inner state city hinders the generalizability of our results. Future studies should include larger samples, the investigation of the factor structure of the Brazilian PCL-5, assessments of the concurrent and divergent validity of the instrument, and separate assessments of the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5.

In summary, the present study provides relevant evidence regarding the reliability and diagnostic utility of the complete and abbreviated versions of the Brazilian PCL-5. Given the relevance of trauma exposure to healthcare systems, this instrument may be a useful and reliable measure for screening patients for further evaluation of a possible PTSD diagnosis. Additionally, our results also support the use of the PCL-5 and its abbreviated versions for research use with Brazilian samples.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author [FLO]. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions imposed by the Institutional Review Board and Informed Consent terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Ashbaugh A. R., Houle-Johnson S., Herbert C., El-Hage W., & Brunet A. (2016). Psychometric validation of the English and French versions of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PloS one, 11(10), e0161645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins C. A., Weathers F. W., Davis M. T., Witte T. K., & Domino J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonett D. G. (2002). Sample size requirements for testing and estimating coefficient alpha. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 27(4), 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Bovin M. J., Marx B. P., Weathers F. W., Gallagher M. W., Rodriguez P., Schnurr P. P., & Keane T. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–Fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First, M.B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S. & Spitzer, R. L. (2016). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gliem J. A., & Gliem R. R. (2003). Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for Likert-type scales. Midwest Research to Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, Columbus, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp (2012). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 21.0). Armonk, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Koo T. K., & Li M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger-Gottschalk A., Knaevelsrud C., Rau H., Dyer A., Schäfer I., Schellong J., & Ehring T. (2017). The German version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeflang M. M. G., Moons K. G. M., Reitsma J. B., & Zwinderman A. H. 1 (2008). Bias in sensitivity and specificity caused by data-driven selection of optimal cutoff values: Mechanisms, magnitude, and solutions. Clinical Chemistry, 54(4), 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MedCalc (2018). MedCalc software. Ostend, Belgium: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Mukaka M. M. (2012). A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Medical Journal, 24(3), 69–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio F. L., Silva T. D. A. D., Santos R. G. D. O. S., Chagas M. H. N., Chagas N. M. S., Sanches R. F., & Crippa J. A. D. E. S. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Transcultural adaptation of the Brazilian version. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 44(1), 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. A. (1994). A meta-analysis of cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(2), 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Price M., Szafranski D. D., van Stolk-Cooke K., & Gros D. F. (2016). Investigation of abbreviated 4 and 8 item versions of the PTSD checklist 5. Psychiatry Research, 239, 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveen J., Bondjers K., & Willebrand M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5: A pilot study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 30165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm J. C., Jordan S., & Bach B. (2016). The personality inventory for DSM-5 short form (PID-5-SF): Psychometric properties and association with big five traits and pathological beliefs in a Norwegian population. BMC Psychology, 4(61). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhey R., Chibanda D., Gibson L., Brakarsh J., & Seedat S. (2018). Validation of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist–5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F. W., Litz B. T., Herman D. S., Huska J. A., & Keane T. M. (1993). The PTSD checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F. W., Litz B. T., Keane T. M., Palmieri P. A., Marx B. P., & Schnurr P. P. (2013). The ptsd checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Wortmann J. H., Jordan A. H., Weathers F. W., Resick P. A., Dondanville K. A., Hall-Clark B., … Hembree E. A. (2016). Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author [FLO]. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions imposed by the Institutional Review Board and Informed Consent terms.