ABSTRACT

Objective: Doctor-shopping has significant consequences for patients and payers and can indicate misuse of drugs, polypharmacy, less continuity of care, and increased medical expenses. This study reviewed the literature describing doctor-shoppers in the adult population.

Methods: A systematic literature review was performed in PubMed and supplemented by a Google search of grey literature. Overall, 2885 records were identified; 43 papers served as a source of definition of a doctor-shopper, disease, treatment, patient characteristics, patient special needs, country.

Results: Definitions of doctor-shopping were heterogeneous. Overall, 40% of studies examined the use of opioids, antidepressants, or psychoactive drugs, while the others focused on chronic or frequent diseases. Most studies were conducted in countries with easy access to healthcare resources (USA, France, Taiwan, Hong Kong). The prevalence of doctor-shopping ranged from 0.5% among opioid users in the USA to 25% of patients registered at general practices in Japan. Comorbidities, active substance abuse, greater distance from healthcare facility, younger age, longer disease and poor patient satisfaction increased doctor-shopping.

Conclusions: Knowing the characteristics of doctor-shoppers may help identify such patients and reduce the associated waste of medical resources, but concerns about the misuse of drugs or healthcare resources should not prevent proper disease management.

KEYWORDS: Doctor-shopping, doctor-shopper, drug abuse, drug misuse, healthcare utilization, physician switching, second opinion patients

Introduction

Doctor-shopping involves visiting multiple doctors with the same health problem and is often observed in outpatient clinics. It has significant consequences for patients and payers, because multiple consultations and overlapping prescriptions are associated with drug misuse, polypharmacy, and increased medical expenses. Changing doctors for the same illness episode without a referral and a link to a history of previous treatment reduces healthcare providers’ ability to ensure effective and efficient treatment [1–3]. Also, rising expectations of receiving high-quality healthcare have been reported to have an impact on the patient–doctor relationship and to contribute to a switch of doctor [4,5].

On one hand, patients are entitled to seek high-quality healthcare, but on the other hand, excessive searching for a second opinion contributes to increased costs of treatment and reduces continuity of care. There are many reasons why patients engage in doctor-shopping. Reports from the literature highlight the importance of factors affecting accessibility to healthcare facilities, such as location, opening hours, and waiting times [6–8]. Patients visit more doctors when they have a chronic disease or a drug addiction and their health problem remains unresolved despite receiving treatment [9–11]. Among factors that reduce doctor-shopping are a proper diagnosis, high patient satisfaction and a good patient–doctor relationship [12,13].

Extensive studies of doctor-shopping in a broad population of patients have not been published in the literature. There is still an ongoing debate among researchers on definitions used to measure this phenomenon and on how to evaluate its impact on patient well-being and healthcare resource use. We conducted this study in order to improve our knowledge of doctor-shopping and to focus the attention of healthcare providers on its reasons and consequences.

Objective

The aim of this study was to review the literature describing doctor-shoppers in the adult population and to identify factors associated with doctor-shopping behaviour.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed in PubMed and supplemented by a Google search of grey literature. The search in PubMed was run on the 28 May 2018. No restrictions regarding timeframe and geographical scope were applied. Eligibility criteria were defined according to the PICOS approach and are presented in Table 1. A first reviewer screened records and abstracts as well as selected studies for qualitative analysis and extracted data from selected publications. Doubtful cases were discussed with a second reviewer, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The electronic search strategy is presented in Table 2. The following data were extracted: definition of doctor-shopper, disease, treatment, patient characteristics, doctor-shopping rate, special patient needs, and country.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| PICO | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults; patients with any disease in outpatient or inpatient settings. | – |

| Intervention | Any intervention or diagnostic procedure. | – |

| Comparator | None required. | – |

| Outcome | Doctor switch. | – |

| Study design | Cohort study; RCT; case report; abstract; database analysis. | Review; letter to the editor; editorial; opinion. |

Table 2.

Electronic search strategy in PubMed.

| ID | Search terms | Number of PubMed hits |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Doctor shopping[Text Word] | 153 |

| #2 | Doctor shopper[Text Word] | 8 |

| #3 | Physician shopping[Text Word] | 2 |

| #4 | Physician shopper[Text Word] | 28 |

| #5 | Double doctoring[Text Word] | 4 |

| #6 | Drug seeking patient[Text Word] | 10 |

| #7 | (physician) AND switch* | 2514 |

| #8 | (doctor) AND switch* | 1959 |

| #9 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 | 2837 |

Results

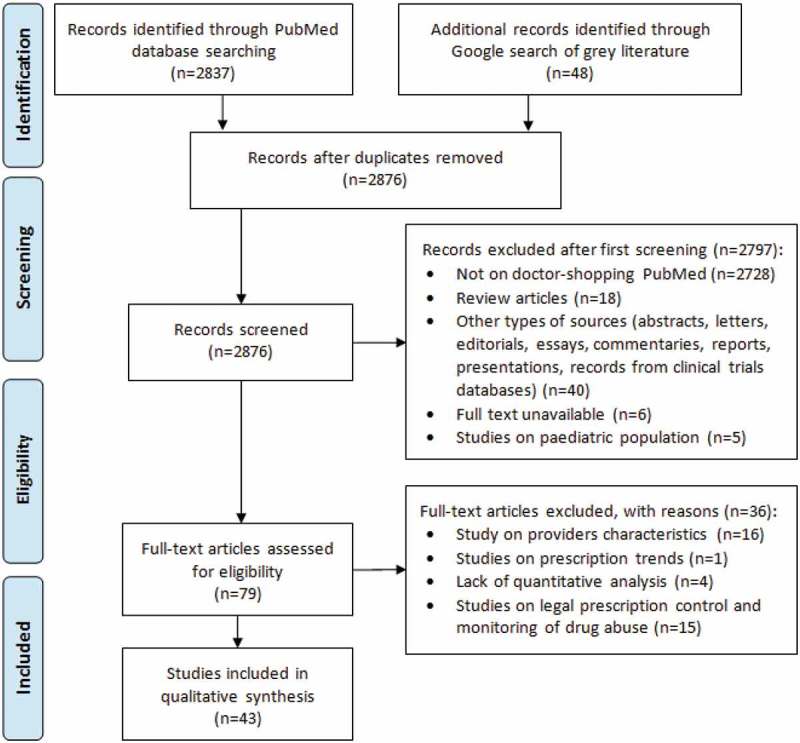

Overall, 2885 records were identified in PubMed and 48 in the grey literature, out of which 43 were included in the qualitative synthesis. A PRISMA flow diagram of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Definition of doctor-shopping

Definitions of doctor-shopping were heterogeneous. The type of the definition depended mostly on the drug and disease studied and the type of source data used in each specific study. The most consistent definitions were used in studies on drug misuse, especially opioids, in which researchers retrospectively evaluated prescriptions using IMS prescription databases or insurance databases. These studies were based on calculations of daily dose that enabled detection of drug overdosing and monitoring the numbers of prescriptions written by different doctors [11,14–19]. Some studies also included information on the number of pharmacies involved [20–25]. Clinical trials and surveys used definitions based on the number of visits during the same illness episode or for the same, often chronic, condition without or within a specified timeframe and without a professional referral. In studies enrolling patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes [7], eye floaters [26], or nephrolithiasis[9], the definition of doctor-shopping specified a higher number of visits, whereas in cases of urgent conditions or infections, definitions specified a timeframe and were, for example, limited to one day [27] or to the same illness episode [6,10,12,28–34]. Studies focusing on the evaluation of doctor-shopping in general medicine or primary doctor facilities had longer timeframes of 1 year [35,36], 2 years [37], or even 3 years [38]. Definitions of doctor-shopping in the studies identified are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Definitions of doctor-shopping.

| Reference | Definition | Type of study | Disease/drug |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cepeda 2013 [24] | >1 prescription by ≥2 different prescribers with ≥1 day of overlap and filled at ≥3 pharmacies. | Retail prescription database | Opioids (tapentadol IR, oxycodone |

| Cepeda 2013 [25] | Retail prescription database | IR) | |

| Cepeda 2015 [23] | Retail prescription database | Opioids | |

| Chenaf 2016 [20,21] | EGB database | ADHD | |

| Delorme 2016 [22] | EGB database | Codeine, tramadol, chronic pain | |

| Buprenorphine, naloxone, methadone | |||

| Lu 2015 [14] | ≥2 prescriptions by different doctors within ≥ 1 day overlapping in the duration of therapy. | Insurance database | Insomnia, zolpidem |

| McDonald 2014 [15] | Retail prescription database | Opioids | |

| Nordmann 2013 [16] | GHI reimbursement database | Opioids | |

| Ponte 2018 [11] | Insurance database | Opioids | |

| Pradel 2010 [17] | Insurance database | Benzodiazepines | |

| Rouby 2012 [18] | Insurance database | Tianeptine | |

| Simeone 2017 [19] | IMS database | Opioids | |

| Martyres 2004 [39] | >1 prescription without specified dose overlap or number of prescribers. | Database study | Heroin-related overdose |

| Morris 2014 [40] | Prospective study + database study | Narcotics, orthopaedic trauma | |

| Okumura 2016 [48] | Insurance database | Benzodiazepines | |

| Pradel 2004 [45] | Prescription database | Buprenorphine | |

| Agrawal 2016 [7] | Visiting ≥1–5 doctors during the same illness episode. | Questionnaire | Diabetes |

| Chang 2012 [28] | Insurance database | Colorectal cancer | |

| Feng 2013 [35] | Questionnaire | Overweight | |

| Gudzune 2014 [13] | Internet-based survey | Overweight | |

| Gudzune 2013 [37] | Claims data, health risk assessments | Overweight | |

| Kappa 2016 [9] | Retrospective study, medical records | Nephrolithiasis, opioids | |

| Leug 2006 [29] | Case-control study | General practitioner facility | |

| Leug 2003 [6] | Cross-sectional survey | General practitioner facility | |

| Lin 2015 [46] | Database study | Traditional Chinese medicine users | |

| Lo 1994 [10] | |||

| Database study | Government outpatient departments | ||

| Norton 2011 [30] | Questionnaire | Primary care facility | |

| Ohira 2012 [12] | Questionnaire | General medicine | |

| Safran 2001 [38] | |||

| Observational study, questionnaire | Primary care facility | ||

| Sato 1999 [31] | |||

| Questionnaire | Primary care facility | ||

| Sato 1995 [32] | |||

| Questionnaire | Primary care, alternative medicine | ||

| Siu 2014 [33] | |||

| Interview | Overactive bladder | ||

| Sorbero 2003 [36] | |||

| Tseng 2015 [26] | Database study | General medicine | |

| Wang 2010 [34] | Questionnaire | Eye floaters | |

| Yeung 2004 [8] | Cohort database study | Respiratory infection | |

| Wu 2014 [27] | Telephone interview | Specialist outpatient clinics | |

| Database study | General practitioner facility | ||

| Lee 2011 [41] | Visiting healthcare providers with a special aim. | Telephone survey | Demand for advertised drugs |

| Stogner 2014 [42] | Survey | Drug abuse or resell | |

| Zhang 2017 [43] | Database study | Price-shopping | |

| Worley 2014 [44] | Study focused on experience. | Interview | Drug abuse during pregnancy |

| Hsieh 2013 [47] | Hospital change | Retrospective longitudinal study | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; EGB, Echantillon Generaliste des Beneficiaires; GHI, general health insurance; IR, immediate release.

Geographical scope of studies on doctor shopping

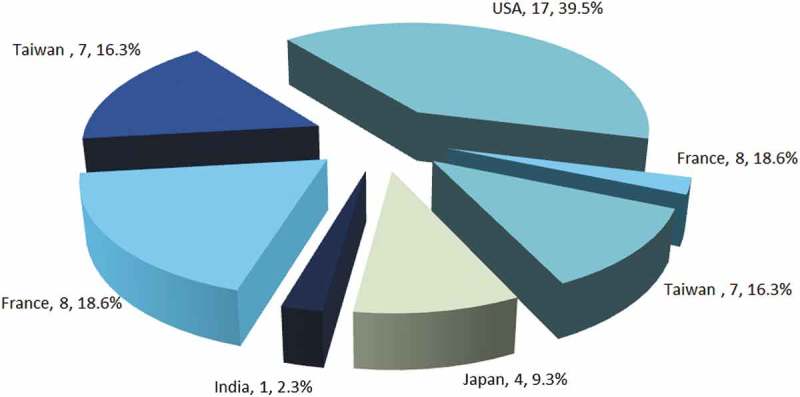

Overall, 17 (39.5%) studies were conducted in the USA, out of which 9 were based solely on retrospective data from large databases [9,11,13,15,19,23–25,36–44]. Another 8 (18.6%) studies were conducted in France [16–18,20–22,30,45], 7 (16.3%) in Taiwan [14,26–28,34,46,47], 5 (11.6%) in Hong Kong [6,8,10,29,33], and 4 (9.3%) in Japan [12,31,32,48]. There was a one study from Australia and one from India [7,35]. The studies were performed in countries where patients can visit medical institutions freely under the national health system and/or have access to all institutions and specialists without a referral. The distribution of countries studied is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of the studies analysed.

Rate of doctor-shopping

Overall, 16 (40%) of studies examined the use of strong, addictive drugs such as opioids, antidepressants, or psychoactive drugs, while the others included patients with chronic (e.g., diabetes, cancer, overactive bladder) or frequent disease (e.g., upper respiratory tract infections). The prevalence of doctor-shopping ranged from 0.5% among opioid users in the USA to 38% of patients registered at general practices in Hong Kong. Examples of rates of doctor-shopping across studies that used different methodologies are shown in Table 4. The rate of doctor-shopping varied considerably depending on the disease, the drug studied, and the type of medical service used. The most reliable precise data were provided for database studies on opioid use. These studies also had the lowest risk bias, because they enabled prescriptions and sales of the drugs prescribed to be tracked in retail prescription databases. Studies including patients registered at outpatient and specialist clinics were mostly based on questionnaires that used different timeframes, small samples, and lacked information about people who refused to participate.

Table 4.

Rates of doctor-shopping across identified studies.

| Disease/drug | Reference/region | Sample size | Rate of doctor-shopping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulants, ADHD | Cepeda 2015 [23] | 4,402,464 | 0.45% any type of shopping behaviour |

| USA | 0.05% heavy shopping behaviour | ||

| Opioids | Cepeda 2013 [25] | 10,910,451 | 0.7% any type of shopping behaviour |

| USA | 0.1% heavy shopping behaviour | ||

| Opioids, non-cancer pain |

Chenaf 2016 [20] | 1958 | 4.03% for codeine |

| France | 0.17% for diuretics | ||

| 8.45% for buprenorphine maintenance treatment | |||

| Opioids | Delorme 2016 [22] | 2043 | 8.4% for high dosage buprenorphine |

| France | 0% for methadone | ||

| 0.2% for diuretics | |||

| Opioids, nephrolithiasis | Kappa 2016 [9] USA |

200 | 24% received narcotics from ≥1 provider after surgery |

| Zolpidem, insomnia | Lu 2015 [14] Taiwan |

6947 | 23.78% for zolpidem |

| General population | Lee 2011 [41] USA |

2998 | 14% of participants whose doctor refused to prescribe a drug switched doctor |

| Patients of specialist outpatient clinics | Leung 2003 [6] Hong Kong |

6495 | 26.4% of population requiring specialist care |

| Government outpatient departments | Lo 1994 [10] Hong Kong |

1387 | 36%-38% during single illness episode |

| General medicine | Sato 1995 [32] Japan |

758 | 24.4% visited >1 medical facility with the same complaint |

| Eye floaters | Tseng 2015 [26] Japan |

134 | 35% visited >1 ophthalmologist |

Factors affecting the rate of doctor-shopping

Risk factors for and protective factors against doctor-shopping have been evaluated in multiple studies. Factors associated with doctor-shopping included predominantly the nature of the disease and comorbidities. Both types of doctor-shoppers (opioid users and patients registered at general and primary doctor practices) shared the same risk factors, such as the presence of mental health disorders, alcohol dependence, and a history of alcohol and active substance misuse disorders [9,22,23,30,31,36,40]. Doctor-shoppers were younger and had a lower socioeconomic status than non-doctor-shoppers, particularly among people who misused opioids [9,20,21,23]. Patients with chronic diseases, multiple comorbidities, and persistent symptoms were more likely to visit a larger number of healthcare providers [10,14,37,41,46,47,48]. A good relationship with a doctor and positive experiences were factors that helped to prevent doctor-shopping [33,38]. Individuals who consumed opioids and drugs for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and engaged in doctor-shopping were more likely to pay cash and to travel great distances to doctor facilities or pharmacies [19,24]. Factors contributing to the development of doctor-shopping are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Factors affecting the rate of doctor-shopping.

| Disease/drug | Reference | Risk factors |

|---|---|---|

| Opioid users | Cepeda 2015 [23] Delorme 2016 [22] |

Presence of mental health disorders; alcohol dependence; low-income status. |

| Pain | Chenaf 2016 [20] | Presence of mental health disorders; history of opioid and substance misuse disorders; doctor-shoppers were of younger age and lower income status. |

| Post-surgery due to nephrolithiasis; opioids. | Kappa 2016 [9] | History of mental illness; prior stone procedures; history of preoperative narcotic misuse; younger age; lower income status; less educated. |

| Orthopaedic trauma | Morris 2014 [40] | History of preoperative narcotic misuse; concomitant alcohol misuse; less educated. |

| Benzodiazepines | Okumura 2016 [48] | Multiple chronic conditions. |

| Insomnia | Lu 2015 [14] | Greater number of comorbidities; chronic diseases; younger age; high socioeconomic status. |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Hsieh 2013 [47] | Hepatitis B carriers; recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma; younger age; female. |

| Overactive bladder | Siu 2014 [33] | Negative treatment experiences. |

| Overweight | Gudzune 2013 [37] | Greater number of comorbidities; mental health diagnosis; diabetes mellitus diagnosis. |

| TCM users | Lin 2015 [46] | Presence of catastrophic illness; history of hospital admission; acupuncture; trauma; dislocation; low income. |

| Outpatient clinic | Lo 1994 [10] | Presence of chronic or acute conditions; persistent symptoms. |

| Primary care | Norton 2011 [30] | Presence of psychiatric and mental disorders. |

| Primary care | Safran 2001 [38] | Poor doctor–patient relationship. |

| General medicine | Lee 2011 [41] | Presence of cancer and other chronic conditions. |

| General medicine | Sato 1999 [31] | Duration of illness; presence of psychiatric disorders; perceived poor and deteriorating health condition; less educated. |

| General medicine | Sorbero 2003 [36] | Multiple comorbid conditions; history of drug/alcohol misuse; younger age; female. |

TCM, traditional Chinese medicine users.

Discussion

This systematic review of the literature showed that doctor-shopping is a common phenomenon. The rate of this phenomenon varies among patient populations with different health problems. For opioids, it can be as low as 0.45% among the broad population that uses opioids, or as high as 24% among patients with a specific reason for opioid use, such as recent surgery for nephrolithiasis. The highest rates were reported for multiple visits to doctors during the same illness episode and were found to involve as many as 38% of patients registered at outpatient clinics. Multiple factors were identified as potential risk factors for doctor-shopping. The most common were multiple comorbid conditions including mental disorders, unresolved health problems, history of drug and other substance misuse, younger age, and poor socioeconomic status. Factors such as a good patient–doctor relationship and a positive patient experience may reduce the rate of doctor-shopping.

Doctor-shopping can signal problems of healthcare system and drug overuse resulting in worsening of health condition of doctor-shoppers. A negative impact of polypharmacy on health has been well documented in the literature [49]. Also, changing doctors reduces continuity of care which can translate into worse disease management and increased waiting times as well as increased cost of treatment for both the patients and payers [50]. Another reason for analysing the phenomenon of doctor shopping is drug abuse. According to police and regulatory agency perceptions, about 40% of prescription drug diversions were sourced from doctor-shopping; however, many other mechanisms such as thefts, forgeries, smuggling, insurance frauds, internet purchase, in-transit losses, and physician ‘pill-mills’ were also identified [51].

The extent and interest in analysis doctor-shopping depend on the healthcare system structure. The country where the study was conducted is an important factor that may influence the rate of doctor-shopping. In some countries, e.g., in Taiwan, patients have access without restrictions to all institutions and specialists [52]. Similarly, in Japan patients can visit medical institutions freely under the national health system [12]. In such cases, the absence of a mandatory attempt to treat the condition by a primary care physician (gate keeper) before a referee to a specialist may increase doctor-shopping behaviour [47]. In France, visiting another general practitioner requires a small additional payment; however, drugs are prescribed for a shorter period (a maximum of 30 days) compared to other countries [16,18]. In the UK, patients have more difficulties with changing doctors, because many general practitioners do not accept patients from outside their own catchment area. Additionally, it is more difficult to access specialist care in the UK. Unfortunately, no studies from the UK were identified, so an evaluation of the impact of accessibility to healthcare on the rate of doctor-shopping was not possible.

Heterogeneity in the definitions of the doctor-shopping was linked to heterogeneity in the data sources. Studies using prescription databases or insurance claims assessed the number of overlapping prescriptions, whereas studies using surveys as a source of information evaluated the number of visits to doctors. This organisation of research does not give a full picture of the problems associated with doctor-shopping. The analysis of overlapping prescriptions provides information only about the misuse of selected drugs, but leaves problems such as polypharmacy, comorbidities, and effectiveness of treatment of the primary disease undiscussed. Individuals who misuse certain agents from different classes, e.g., opioids, stimulants, and benzodiazepines, might not be identified as doctor-shoppers in these analyses.

The main limitation of surveys is that participants who complete questionnaires may conceal information about addictions, drug misuse or a true reason for a doctor-shopping. The limitation of claims-based study, although giving accurate information, includes possible discrepancies between claims and patient behaviours; claims for prescriptions do not always indicate that the medication was taken as prescribed.

Prescription drug monitoring programmes that aim to reduce drug abuse report that the number of overall drug prescriptions per person is lower when a patient is on a single schedule in comparison to the number of prescriptions filled for individuals prescribed drugs in multiple schedules [53,54]. This finding is intuitive, but highlights the possible risks associated with polypharmacy, which is often rooted in a greater number of comorbidities. The presence of multiple comorbidities, both mental and somatic, was identified as a risk factor for doctor-shopping [9,23,31,36,48].

Little is known on the effective long-term initiatives to reduce doctor-shopping especially in terms of eliminating drug interactions, errors in dosing and polypharmacy. Programs based on the promotion of medication reviews and education of physicians and patients were found to be effective. However, they face problems with the identification of patients at risk for polypharmacy or drug abuse [55]. Computerized physician order entry, clinical decision support, and electronic prescriptions systems showed the ability to diminish medication errors in specific therapeutic areas in monitored patients [56,57]. Introduction of electronic insurance cards with health information and medication history would offer benefits when introduced nationally; however, such solutions require investments in infrastructure [58]. Moreover, Taiwanese experience shows that only 73% of physicians review their prescriptions in response to displayed alerts [59]. The obstacles mentioned above highlight challenges in the development of useful, easy to use and cheap solution for optimising pharmacological treatment in patients at risk for polypharmacy or drug abuse.

Conclusions

Knowing the characteristics of doctor-shoppers may help identify such patients and reduce the associated waste of medical resources, but concerns about the misuse of drug or healthcare resources should not prevent proper disease management. Further research is needed to cover a wider range of diseases and countries, and to examine the effect of healthcare regulations on doctor-shopping prevalence and costs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Presentations

The abstract and poster of this study were presented at ISPOR Europe 2018, 10–14 November 2018, Barcelona, Spain.

References

- [1].Suzuki Y, Sakakibara M, Shiraishi N, et al. Prescription of potentially inappropriate medications to older adults. A nationwide survey at dispensing pharmacies in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;77:8–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kadam UT.Potential health impacts of multiple drug prescribing for older people: a case-control study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(583):128–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sutherland JJ, Daly TM, Liu X, et al. Co-prescription trends in a large cohort of subjects predict substantial drug-drug interactions. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0118991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lynch DJ, McGrady AV, Nagel RW, et al. The patient-physician relationship and medical utilization. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(4):266–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schwenk TL, Marquez JT, Lefever RD, et al. Physician and patient determinants of difficult physician-patient relationships. J Fam Pract. 1989;28(1):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Leung GM, Castan-Cameo S, McGhee SM, et al. Waiting time, doctor shopping, and nonattendance at specialist outpatient clinics: case-control study of 6495 individuals in Hong Kong. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1293–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Agrawal S, Lakshminarayanan S, Kar S. Doctor-shopping behavior among diabetic patients in urban Puducherry. Int J Adv Med Health Res. 2016;3(1):20–24. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yeung RY, Leung GM, McGhee SM, et al. Waiting time and doctor shopping in a mixed medical economy. Health Econ. 2004;13(11):1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kappa SF, Green EA, Miller NL, et al. Narcotic use and postoperative doctor shopping by patients with nephrolithiasis requiring operative intervention: implications for patient safety. J Urol. 2016;196(3):763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lo AY, Hedley AJ, Pei GK, et al. Doctor-shopping in Hong Kong: implications for quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994;6(4):371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ponte C, Lepelley M, Boucherie Q, et al. Doctor shopping of opioid analgesics relative to benzodiazepines: A pharmacoepidemiological study among 11.7 million inhabitants in the French countries. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ohira Y, Ikusaka M, Noda K, et al. Consultation behaviour of doctor-shopping patients and factors that reduce shopping. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(2):433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gudzune KA, Bennett WL, Cooper LA, et al. Prior doctor shopping resulting from differential treatment correlates with differences in current patient-provider relationships. Obesity. 2014;22(9):1952–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lu TH, Lee YY, Lee HC, et al. Doctor shopping behavior for zolpidem among insomnia patients in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Sleep. 2015;38(7):1039–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McDonald DC, Carlson KE. The ecology of prescription opioid abuse in the USA: geographic variation in patients’ use of multiple prescribers (“doctor shopping”). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(12):1258–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nordmann S, Pradel V, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. Doctor shopping reveals geographical variations in opioid abuse. Pain Physician. 2013;16(1):89–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pradel V, Delga C, Rouby F, et al. Assessment of abuse potential of benzodiazepines from a prescription database using ‘doctor shopping’ as an indicator. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(7):611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rouby F, Pradel V, Frauger E, et al. Assessment of abuse of tianeptine from a reimbursement database using ‘doctor-shopping’ as an indicator. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2012;26(2):286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Simeone R. Doctor shopping behavior and the diversion of prescription opioids. Subst Abuse Res Treat. 2017;11:1178221817696077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chenaf C, Kabore JL, Delorme J, et al. Codeine shopping behavior in a retrospective cohort of chronic noncancer pain patients: incidence and risk factors. J Pain. 2016;17(12):1291–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chenaf C, Kabore JL, Delorme J, et al. Incidence of tramadol shopping behavior in a retrospective cohort of chronic non-cancer pain patients in France. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(9):1088–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Delorme J, Chenaf C, Kabore JL, et al. Incidence of high dosage buprenorphine and methadone shopping behavior in a retrospective cohort of opioid-maintained patients in France. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cepeda MS, Fife D, Berwaerts J, et al. Doctor shopping for medications used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: shoppers often pay in cash and cross state lines. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(3):226–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cepeda MS, Fife D, Vo L, et al. Comparison of opioid doctor shopping for tapentadol and oxycodone: a cohort study. J Pain. 2013;14(2):158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cepeda MS, Fife D, Yuan Y, et al. Distance traveled and frequency of interstate opioid dispensing in opioid shoppers and nonshoppers. J Pain. 2013;14(10):1158–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tseng GL, Chen CY. Doctor-shopping behavior among patients with eye floaters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(7):7949–7958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu MH, Wu MJ, Chou LF, et al. Patterns of nonemergent visits to different healthcare facilities on the same day: a nationwide analysis in Taiwan. Sci World J. 2014;2014:627580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chang HR, Yang MC, Chung KP. Can cancer patients seeking a second opinion get better care? Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(5):380–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Leung GM, Yeung RY, Wong IO, et al. Time costs of waiting, doctor-shopping and private-public sector imbalance: microdata evidence from Hong Kong. Health Policy. 2006;76(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Norton J, de Roquefeuil G, David M, et al. The mental health of doctor-shoppers: experience from a patient-led fee-for-service primary care setting. J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1–3):428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sato T, Takeichi M, Hara T, et al. Second opinion behaviour among Japanese primary care patients. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(444):546–550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sato T, Takeichi M, Shirahama M, et al. Doctor-shopping patients and users of alternative medicine among Japanese primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17(2):115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Siu JY. “Seeing a doctor is just like having a date”: a qualitative study on doctor shopping among overactive bladder patients in Hong Kong. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang MJ, Lin SP. Study on doctor shopping behavior: insight from patients with upper respiratory tract infection in Taiwan. Health Policy. 2010;94(1):61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Feng X. On the relationship between weight status and doctor shopping behavior-evidence from Australia. Obesity. 2013;21(11):2225–2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sorbero ME, Dick AW, Zwanziger J, et al. The effect of capitation on switching primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(1 Pt 1):191–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gudzune KA, Bleich SN, Richards TM, et al. Doctor shopping by overweight and obese patients is associated with increased healthcare utilization. Obesity. 2013;21(7):1328–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Safran DG, Montgomery JE, Chang H, et al. Switching doctors: predictors of voluntary disenrollment from a primary physician’s practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Martyres RF, Clode D, Burns JM. Seeking drugs or seeking help? Escalating “doctor shopping” by young heroin users before fatal overdose. Med J Aust. 2004;180(5):211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Morris BJ, Zumsteg JW, Archer KR, et al. Narcotic use and postoperative doctor shopping in the orthopaedic trauma population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(15):1257–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lee D, Begley CE. Physician switching after drug request refusal. Health Mark Q. 2011;28(4):304–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stogner JM, Sanders A, Miller BL. Deception for drugs: self-reported “doctor shopping” among young adults. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(5):583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhang X, Haviland A, Mehrotra A, et al. Does enrollment in high-deductible health plans encourage price shopping? Health Serv Res. 2018;53(Suppl 1):2718–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Worley J. Identification and management of prescription drug abuse in pregnancy. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2014;28(3):196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pradel V, Thirion X, Ronfle E, et al. Assessment of doctor-shopping for high dosage buprenorphine maintenance treatment in a French region: development of a new method for prescription database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(7):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lin MH, Chang HT, Tu CY, et al. Doctor-shopping behaviors among traditional Chinese medicine users in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9237–9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hsieh CI, Chung KP, Yang MC, et al. Association of treatment and outcomes of doctor-shopping behavior in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Okumura Y, Shimizu S, Matsumoto T. Prevalence, prescribed quantities, and trajectory of multiple prescriber episodes for benzodiazepines: A 2-year cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Chang YP, Huang SK, Tao P, et al. A population-based study on the association between acute renal failure (ARF) and the duration of polypharmacy. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mendes FR, Gemito ML, Caldeira ED, et al. Continuity of care from the perspective of users. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22(3):841–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, et al. Mechanisms of prescription drug diversion among drug-involved club- and street-based populations. Pain Med. 2007;8(2):171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wu T-Y, Majeed A, Kuo KN. An overview of the healthcare system in Taiwan. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2010;3(2):115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Scott R, Philip C, Poston R. Prescription drug monitoring program. 2016. cited 2018 September01 Available from: http://www.floridahealth.gov/statistics-and-data/e-forcse/_documents/2016PDMPAnnualReport.pdf

- [54].McPheeters ML, Nechuta S, Miller S, et al. Prescription drug overdose program 2018 report: understanding and responding to the opioid epidemic in Tennessee using mortality, morbidity, and prescription data. 2018. cited 2018 September01 Available from: https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/documents/pdo/PDO_2018_Report_02.06.18.pdf

- [55].Fillit HM, Futterman R, Orland BI, et al. Polypharmacy management in Medicare managed care: changes in prescribing by primary care physicians resulting from a program promoting medication reviews. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(5):587–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kaushal R, Shojania KG, Bates DW. Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review. Arch Internal Med. 2003;163(12):1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sinnemaki J, Airaksinen M, Valaste M, et al. Impact of the automated dose dispensing with medication review on geriatric primary care patients drug use in Finland: a nationwide cohort study with matched controls. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;35(4):379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lux A. Cost-benefit analysis of a new health insurance card and electronic prescription in Germany. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8(Suppl 2):54–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hsu MH, Yeh YT, Chen CY, et al. Online detection of potential duplicate medications and changes of physician behavior for outpatients visiting multiple hospitals using national health insurance smart cards in Taiwan. Int J Med Inform. 2011;80(3):181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]