Abstract

Infectious laryngotracheitis virus (ILTV) is a gallid herpesvirus type 1, a member of the genus Iltovirus. It causes an infection in the upper respiratory tract mainly trachea which results in significant economic losses in the poultry industry worldwide. Vaccination against ILTV produced latent infected carriers' birds, which become a source of virus transmission to nonvaccinated flocks. Thus this study aimed to design safe multiepitopes vaccine against glycoprotein B of ILT virus using immunoinformatic tools. Forty-four sequences of complete envelope glycoprotein B were retrieved from GenBank of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and aligned for conservancy by multiple sequence alignment (MSA). Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) analysis resources were used to predict and analyze candidate epitopes that could act as a promising peptide vaccine. For B cell epitopes, thirty-one linear epitopes were predicted using Bepipred. However eight epitopes were found to be on both surface and antigenic epitopes using Emini surface accessibility and antigenicity, respectively. Three epitopes (190KKLP193, 386YSSTHVRS393, and 317KESV320) were proposed as B cell epitopes. For T cells several epitopes were interacted with MHC class I with high affinity and specificity, but the best recognized epitopes were 118YVFNVTLYY126, 335VSYKNSYHF343, and 622YLLYEDYTF630. MHC-II binding epitopes, 301FLTDEQFTI309,277FLEIANYQV285, and 743IASFLSNPF751, were proposed as promising epitopes due to their high affinity for MHC-II molecules. Moreover the docked ligand epitopes from MHC-1 molecule exhibited high binding affinity with the receptors; BF chicken alleles (BF2 2101 and 0401) expressed by the lower global energy of the molecules. In this study nine epitopes were predicted as promising vaccine candidate against ILTV. In vivo and in vitro studies are required to support the effectiveness of these predicted epitopes as a multipeptide vaccine through clinical trials.

1. Introduction

Infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) is classified as a gallid herpesvirus 1 which belongs to the fay Herpesviridae, genus Iltovirus [1–3]. The virus is included within List E of the Office International des Epizooties (OIE). It causes a major viral respiratory disease of chicken [2]. The disease causes marked economic losses of poultry industry with mortality reaching 70%, especially in high- density poultry-producing regions [3]. High mortality, demonstrated by the severe form of the disease, is a result of severe tracheal lesions in the respiratory tract, significant respiratory distress, expectoration of bloody sputum, sneezing and persistent nasal discharge decreased egg production, weight loss, and susceptibility to infections with other pathogens [4]. The mild form exhibited low mortality, mucoid tracheitis, and sinusitis [5, 6].

Vaccination against the viral diseases is very important for protection, due to the lack of appropriate antiviral drugs, high cost, and time consuming of development of new antiviral drugs. Different types of vaccines are available for ILTV such as vaccines produced in chicken-embryo-origin (CEO), tissue-culture-origin (TCO), and recombinant vaccines [5]. However, vaccination against ILTV is recommended only in endemic areas to prevent transmission of the virus by latent infected carriers' birds to nonvaccinated healthy flocks [1, 7, 8]. Moreover current vaccines are themselves mildly pathogenic and modified live ILT vaccines increase the virulence of the disease by mutation during bird-to-bird passage in the field [2, 9, 10]. DNA encoding glycoprotein B vaccine was found to give levels of protection when given intramuscularly comparable to traditional live-attenuated ILTV vaccines. Glycoprotein B and D genes of ILTV have been used to produce immunogenic proteins to elicit protective immune response. These glycoproteins which are located on the viral envelope and the surface of infected cells are required for viral attachment [1]. Developing of new drugs to treat viral diseases is very expensive and time consuming. Therefore, vaccines remain the best choice to protect animals and humans from viruses and other pathogens. In addition traditional techniques of live-attenuated or inactivated vaccines have the risk of allergic reactions. Peptide vaccines are economically reasonable, require less time for development, and hold the promise of multivalent dosages [11–13]. Recently, bioinformatics software has been used largely to design synthetic peptide vaccines, based on B and T cell responses [14]. The design of multipeptide vaccines using computational model that links various immunoinformatic prediction tools is known to produce satisfactory results [15, 16]. The safety, accuracy, feasibility, and speed of these vaccines were well discussed through various computational studies [17, 18]. Thus, it is essential to design safe effective vaccine against ILTV that prevents birds from being carriers of the disease using bioinformatics tools. The aim of the present study was to design a vaccine for ILT virus using peptides predicted from glycoproteins especially type B as an immunogen to stimulate protective immune response. The reason of selecting glycoprotein B as a target is due to its function in host attachment and in stimulating immune response in the host.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Sequence Retrieval and Phylogeny

Forty-four envelope glycoprotein B (GB) sequences of virulent isolates of ILTV were retrieved from GenBank of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein) in August 2017. The strains of the virus were isolated from chicken from different geographic regions. Complete sequences of all gene subtypes were selected for various immune-bioinformatics analysis. Retrieved strains and their accession numbers and geographical regions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Retrieved strains of ILTV with their date of collection, accession numbers, and geographical regions.

| Accession No | country | Year | Accession No | country | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YP_182356.1∗ | USA | 2005 | AEW67850.1 | USA | 2012 |

| AFV79628.1 | China | 2011 | AEW67771.1 | USA | 2011 |

| ABX59525.1 | ''USA | 2007 | AEB97319.1 | Australia | 2010 |

| ABX59524.1 | USA | 2007 | ABX59533.1 | USA | 2007 |

| ANB43607.1 | Russia | 2000 | ABX59532.1 | USA | 2007 |

| ANF04484.1 | Australia | 2015 | ABX59531.1 | USA | 2007 |

| ANN24991.1 | USA | 2017 | ABX59530.1 | USA | 2007 |

| ANN24921.1 | USA | 2016 | ABX59529.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AJR27653.1 | Italy | 2007 | ABX59528.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AJR27811.1 | Italy | 1980 | ABX59527.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AJR27732.1 | Italy | 2011 | ABX59526.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AJR27574.1 | Italy | 2015 | ABX59523.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AJR27495.1 | Italy | 2015 | ABX59522.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AER28131.1 | Australia | 2011 | ABX59521.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AER28052.1 | Australia | 2011 | ABX59520.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AGN48336.1 | China | 2012 | ABX59519.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AGN48256.1 | China | 2012 | ABX59518.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AGN48178.1 | China | 2009 | ABX59517.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AGC23137.1 | Australia | 1970 | ABX59516.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AGC23058.1 | Australia | 1999 | ABX59515.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AFN02008.1 | Australia | 2011 | ABX59514.1 | USA | 2007 |

| AFN01929.1 | Australia | 2011 | ABX59513.1 | USA | 2007 |

∗Refseq of ILTV envelope glycoprotein B.

2.2. Phylogenetic Evolution

Phylogenetic tree of the retrieved sequences of glycoprotein B of ILTV was created using phylogeny.fr online software (http://phylogeny.lirmm.fr/phylo_cgi/index.cgi) [19].

2.3. Multiple Sequence Alignment

The retrieved sequences of ILTV glycoprotein B (GB) were subjected to multiple sequence alignments (MSA) to obtain the conserve regions. This was performed using BioEdit software version 7.2.5 with the aid of ClustalW as applied in the BioEdit program to construct the alignment [20].

2.4. Sequence-Based Method

The reference sequence (YP_182356.1) of ILT virus glycoprotein B (GB) was submitted to different prediction tools at the Immune Epitope Database analysis resource (http://www.iedb.org/). Epitope analysis resources were used to predict B and T cell epitopes [21]. Predicted epitopes were then investigated in aligned retrieved GB sequences after MSA for conservancy. Conserved epitopes would be considered as candidate epitopes for B and T cells.

2.4.1. B Cell Epitope Prediction

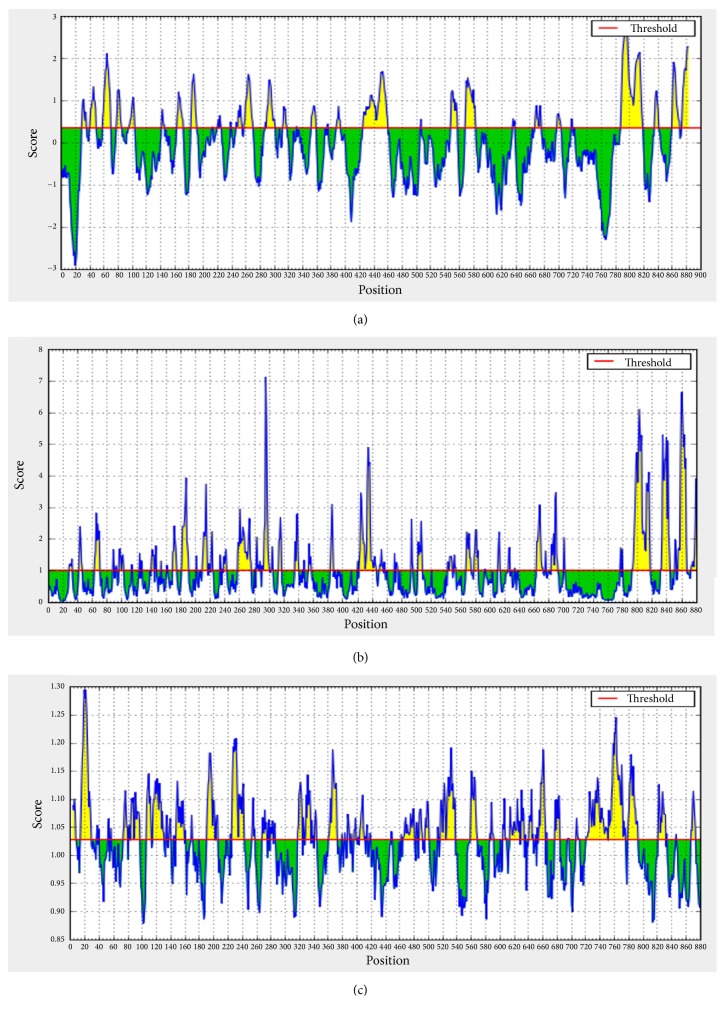

Identification of the surface accessibility, hydrophobicity, flexibility, and antigenicity was performed by analyzing candidate epitopes using several B cell prediction methods from Immune Epitope Database (http://tools.iedb.org/bcell/). BepiPred linear epitope prediction from Immune Epitope Database (http://tools.iedb.org/bcell/result/) was used to predict linear B cell epitopes with default threshold -.012 [22]. Emini surface accessibility prediction tool of IEDB was performed to detect the surface accessible epitopes with default threshold 1.000 [23], while the prediction of epitopes antigenicity sites of candidate epitopes was achieved to identify the antigenic sites using Kolaskar and Tongaonker antigenicity method (http://tools.immuneepitope.org/bcell/) with default threshold 1.027 [24]. The thresholds of these methods are demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prediction of B cell epitopes using (a) Bepipred linear epitope, (b) Emini surface accessibility, and (c) Kolaskar and Tongaonkar Antigenicity methods. Yellow areas above the threshold (red line) are suggested to be a part of B cell epitope, while green areas are not.

2.4.2. T Cell Epitope Prediction

(1) Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Epitopes Prediction and Interaction with MHC- I. The major histocompatibility complex-1 (MHC class I) binding prediction tool (http://tools.iedb.org/mhci/) was used to predict Cytotoxic T cell epitopes [25]. Analysis was achieved using human HLA alleles, due to the lack of chicken alleles in IEDB data set. Artificial neural network (ANN) was used to predict the binding affinity [26, 27]. Peptide length for all selected epitopes was set to 9 amino acids (mers). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values required for the peptide's binding to the specific MHC-I molecules were set less than or equal to 300 nM.

(2) Prediction of T Cell Epitopes and Interaction with MHC Class II. The MHC class II binding prediction tool (http://tools.iedb.org/mhcii/) was used to predict T cell epitopes. IC50 for strong binding peptides was set less than 1000 to determine the interaction potentials of T cell epitopes and MHC class II allele (HLA DR, DP and DQ). Human MHC class I and II alleles were used in this study due to the difficulty to determine MHC B complex alleles in poultry. NN-align method was also used with IC50 less than or equal to 1000 nM [28]. Peptides with low IC50 value were proposed to be promising MHC-II epitopes.

2.5. Homology Modeling

2.5.1. Structural Prediction of the Reference Sequence of ILTV Glycoprotein B

Homology modeling was used for constructing the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the reference sequence of ILTV glycoprotein B. Raptor X structure prediction server (http://raptorx.uchicago.edu/StructurePrediction/predict/) was used for this purpose. The 3D structure was then treated with Chimera software 1.8 to display the position of proposed epitopes [29–32].

2.5.2. Structure of BF Chicken Alleles

Protein sequence and PDB ID of chicken alleles (BF2∗2101 & BF2∗0401) were retrieved from the NCBI database/ (PDB: 4D0C, CAK54661.1 and PDB: 4D0C CAK54660.1) and submitted to Raptor X server (http://raptorx.uchicago.edu/) for homology modeling. Chimera software was used to display 3D structure of BF alleles [29–32].

2.5.3. Structure of Predicted Epitopes

The homology modeling of the MHCI predicted peptides was performed with PEP FOLD3 (http://bioserv.rpbs.univ-paris-diderot.fr/services/PEP-FOLD3/) to predict the linear structures from amino acid sequences [33–35].

2.6. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was performed according to peptide-binding groove affinity, between chicken BF alleles (BF2∗2101 & BF2∗0401) and the proposed peptides from MHCI. Chicken BF alleles were set as receptors and the proposed peptides were set as ligands. Molecular docking technique of 3D structure of BF alleles and 3D modeled epitopes was performed using PatchDock online autodock tools; an automatic server for molecular docking (https://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PatchDock/) by submitting PDB of ligands and receptors after homology modeling by Raptor X server and PEP FOLD3 [36, 37]. Firedock was used to select the best models [38]. Visualization of the result was performed off-line using UCSF-Chimera visualization tool 1.8. [29].

3. Results and Discussion

In the vaccine industry, presenting a specific antigen or a host of antigens to the immune system is necessary to increase immunity against viral diseases. The functional component of the vaccine should be able to stimulate the immune system, by using vaccines containing intact inactive components (attenuated viruses; purified immunogenic parts of the pathogen) to trigger immune response [27, 39]. It is known that the use of whole viral proteins to induce an immune response is not necessarily but small portions of protein called antigenic determinants or adhesive epitopes can be used to stimulate the desired immunity [40].

The use of bioinformatics analyses is an applicable method for predicting and designing new multiepitope vaccines against animals' infectious diseases as well as chickens [17, 41, 42]. This is the first in silico study to design peptide vaccine against avian ILTV through humoral and cell mediated immune responses. The expected epitopes in this study could help in prevention of latent infection caused by the use of attenuated vaccines and developing more effective and trustable prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines than conventional methods.

3.1. Sequences Alignment

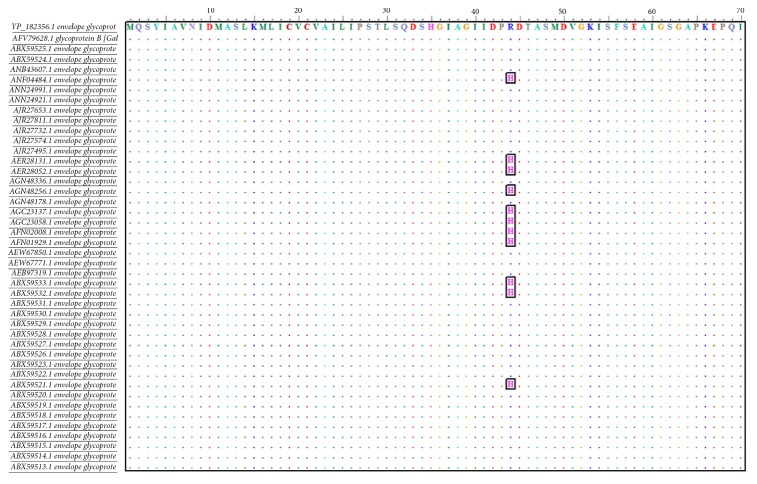

Alignment of all retrieved sequences using ClustalW through BioEdit software showed high conservancy between the aligned sequences. As shown in Figure 2, the conserved regions were recognized by identity and similarity of amino acid sequences.

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of the retrieved strains using BioEdit software and ClustalW. Dots indicated the conservancy and letters in cubes showed the alteration in amino acid.

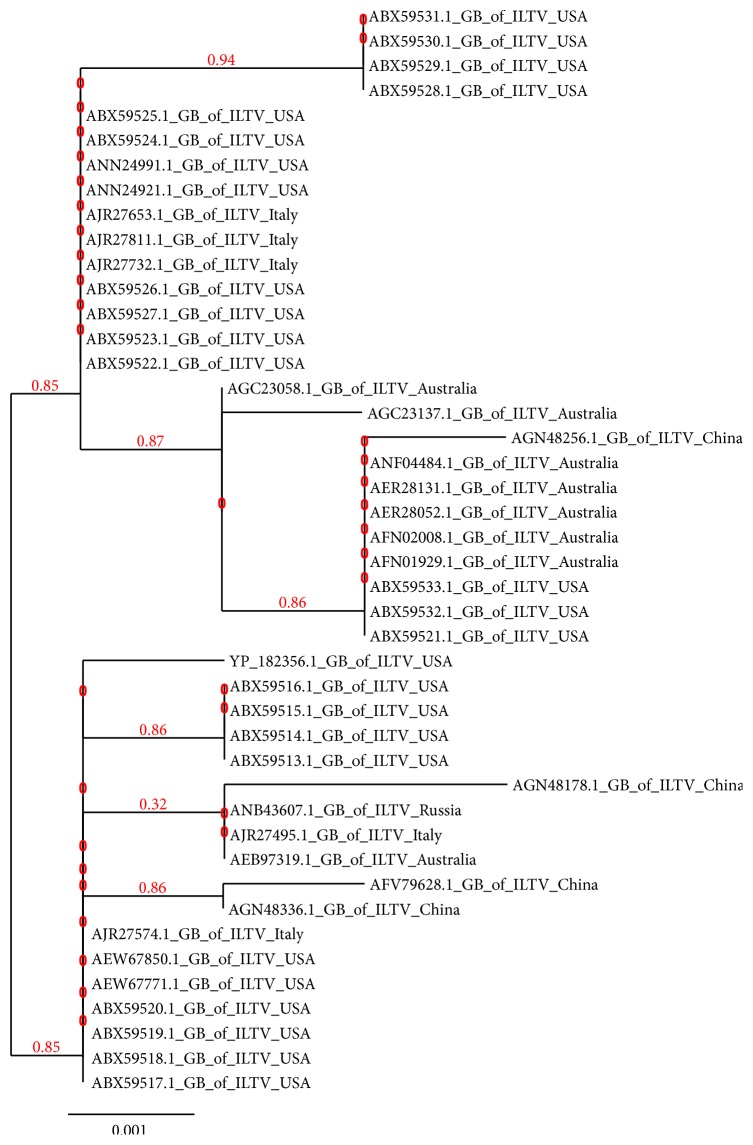

3.2. Phylogenetic Evolution

Phylogenetic tree was created using (http://www.phylogeny.fr). The evolutionary divergence analysis of the enveloped glycoprotein B of the different strains of ILTV is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Evolutionary divergence analysis of enveloped glycoprotein B (GB) of different strains of ILTV.

3.3. Prediction of B Cell Epitopes

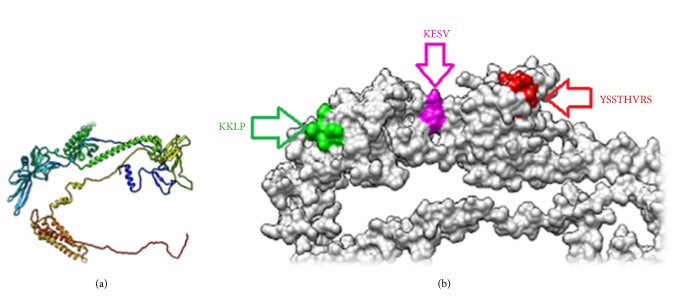

Surface accessibility, hydrophilicity, flexibility, and antigenicity are important B cell antigenic indexes to design peptide vaccine. Investigation of ILTV glycoprotein B using different prediction methods of B cell at the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) revealed varying threshold for different scales (see Figure 1). Thirty-one unique linear epitopes with 4 peptides or more in length were predicted using Bepipred Linear Epitope Prediction method depending on binding affinity to B lymphocytes. Analysis of these epitopes for surface accessibility and antigenicity proposed seventeen and thirteen peptides works as surface and antigenic epitopes, respectively (see Table 2). The predicted epitopes were found of high conservancy when tested in aligned sequences. Of these, only eight epitopes successfully covered all the antigenic indexes of B cell prediction tests. The best B cell predicted epitopes that overlap all B cell prediction methods were 190KKLP193, 386YSSTHVRS393, and 317KESV320. The 3D structure of these predicted epitopes is shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

List of B cell epitopes predicted by different B cell scales.

| No. | Peptide | Start | End | Length | Emini 1000 | Antigenicity 1.027 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QFTI | 306 | 309 | 4 | 0.514 | 1.042 |

| 2 | GQPVS | 518 | 522 | 5 | 0.678 | 1.07 |

| 3 | KLNPNS | 506 | 511 | 6 | 1.715 | 0.968 |

| 4 | NASEIE | 635 | 640 | 6 | 0.888 | 0.951 |

| 5 | LGEVGKA | 718 | 724 | 7 | 0.303 | 1.032 |

| 6 | DAMEEKESV | 312 | 320 | 9 | 1.355 | 0.959 |

| 7 | KESV∗ | 317 | 320 | 4 | 1.168 | 1.044 |

| 8 | EVPEAVRVS | 328 | 336 | 9 | 0.395 | 0.959 |

| 9 | VIRGDRGDA | 697 | 705 | 9 | 0.433 | 0.981 |

| 10 | PQITNEYVTR | 141 | 150 | 10 | 1.433 | 1.009 |

| 11 | EYVTR∗ | 146 | 150 | 5 | 1.465 | 1.035 |

| 12 | TFSSGKQPFN | 351 | 360 | 10 | 0.957 | 0.977 |

| 13 | RSGECSSKATY | 163 | 173 | 11 | 0.837 | 1.01 |

| 14 | YDNDEAEKKLP | 183 | 193 | 11 | 4.592 | 0.964 |

| 15 | KKLP∗ | 190 | 193 | 4 | 1.729 | 1.044 |

| 16 | KDEQKARRQKA | 834 | 844 | 11 | 11.486 | 0.946 |

| 17 | EAIGSGAPKEPQI | 58 | 70 | 13 | 0.374 | 0.997 |

| 18 | HCHRHADSTNMTE | 93 | 105 | 13 | 0.786 | 0.986 |

| 19 | CSSPTGASVARLAQ | 77 | 90 | 14 | 0.103 | 1.072 |

| 20 | YSSTHVRSGDIEYYL | 386 | 400 | 15 | 0.537 | 1.052 |

| 21 | YSSTHVRS∗ | 386 | 393 | 8 | 1.152 | 1.058 |

| 22 | NFTKRHQTLGYRTSTS | 211 | 226 | 16 | 2.246 | 0.976 |

| 23 | RHQTLGY∗ | 215 | 221 | 7 | 1.232 | 1.027 |

| 24 | SSSPESQFSANSTENH | 569 | 584 | 16 | 1.851 | 0.973 |

| 25 | VYTREELRDTGTLNYD | 663 | 678 | 16 | 1.703 | 0.985 |

| 26 | VYTREEL∗ | 663 | 669 | 7 | 1.176 | 1.04 |

| 27 | VRDLETGQIRPPKKRNFL | 285 | 302 | 18 | 1.191 | 1.001 |

| 28 | QIRPP∗ | 292 | 296 | 5 | 1.463 | 1.034 |

| 29 | FGMATGDTVEISPFYTKNTTGPRRHSV | 245 | 271 | 27 | 0.185 | 0.991 |

| 30 | EEAQRQNHLPRGRERRQAAGRRTASLQSGPQGDRITTHSS | 423 | 462 | 40 | 8.232 | 0.969 |

| 31 | QNHLP∗ | 428 | 432 | 5 | 1.243 | 1.042 |

∗Shortened peptide that has high score in both Emini and Kolaskar.

Figure 4.

(a) The reference glycoprotein B of ILTV. (b) The position of proposed B cell epitopes in the 3D structure of reference glycoprotein B of ILTV.

3.4. Prediction of T Cell Epitopes

CD8+ and CD4+ T cells have principal role in stimulation of immune response as well as antigen mediated clonal expression of B cell [14]. Several technical problems challenged the design peptide vaccine against ILTV based on T cytotoxic and T helper epitopes prediction, most importantly, the lack of online bioinformatics database for chicken MHC alleles. For this reason human MHC class I alleles (HLA-A and HLA-B) were used in this study as an alternate alleles to investigate the interaction of epitopes with MHCI using epitope prediction software [43]. Studies have shown that the MHC genes in chickens are classified into MHCI associated genes (B-F) and MHCII (B-L) associated B-G genes [44]. The B-F alleles in chicken were found to be similar in stimulation of immune system to mammalian class I homologs especially in presenting the antigen of T-lymphocyte [45, 46]. MHC class I molecule in the chicken especially BF2∗2101 from the B21 haplotype is highly expressed, leading to strong genetic links with infectious pathogens. In addition, BF2∗2101 from the B21 haplotype has principal role in provoking resistance to Marek's disease caused by an oncogenic herpesvirus [43], to which ILTV belongs.

3.4.1. Prediction of Epitopes Interacted with MHC Class I

MHC-1 binding prediction tool using IEDB database predicted sixteen epitopes that interacted with the cytotoxic T cell as they strongly linked with multiple alleles. As shown in Table 3, MHCI results expected several CTL epitopes. The top epitope was 118YVFNVTLYY126 which interacted and linked with 16 human alleles, followed by 335VSYKNSYHF343 and 622YLLYEDYTF630 as they linked with 9 human MHCI alleles. The 3D structure of the proposed epitopes is shown in Figure 5.

Table 3.

Position of most promising epitopes in the glycoprotein B of ILTV that bind with high affinity with the human MHC class I alleles.

| Peptide | Start | End | Allele | ic50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLICVCVAI | 16 | 24 | HLA-A∗02:01 | 19.5 |

| HLA-A∗02:06 | 27.85 | |||

| HLA-A∗32:01 | 181.4 | |||

| HLA-A∗68:02 | 50.12 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 209.67 | |||

|

| ||||

| YVFNVTLYY∗ | 118 | 126 | HLA-A∗01:01 | 52.47 |

| HLA-A∗03:01 | 31.62 | |||

| HLA-A∗11:01 | 8.01 | |||

| HLA-A∗25:01 | 245.85 | |||

| HLA-A∗26:01 | 7.03 | |||

| HLA-A∗29:02 | 2.26 | |||

| HLA-A∗30:02 | 29.28 | |||

| HLA-A∗68:01 | 10.69 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 41.17 | |||

| HLA-B∗35:01 | 8.03 | |||

| HLA-B∗46:01 | 109.43 | |||

| HLA-B∗58:01 | 103.63 | |||

|

| ||||

| LYYKHITTV | 124 | 132 | HLA-A∗23:01 | 176.88 |

| HLA-A∗24:02 | 255.62 | |||

| HLA-C∗06:02 | 228.43 | |||

| HLA-C∗07:01 | 281.81 | |||

| HLA-C∗12:03 | 40.39 | |||

| HLA-C∗14:02 | 20.88 | |||

|

| ||||

| TTVTTWALF | 130 | 138 | HLA-A∗23:01 | 186.44 |

| HLA-A∗24:02 | 291.18 | |||

| HLA-A∗26:01 | 43.17 | |||

| HLA-A∗29:02 | 140.22 | |||

| HLA-B∗57:01 | 135.77 | |||

| HLA-B∗58:01 | 126.76 | |||

|

| ||||

| MATGDTVEI | 247 | 255 | HLA-A∗02:06 | 298.31 |

| HLA-A∗68:02 | 27.18 | |||

| HLA-B∗35:01 | 70.95 | |||

| HLA-B∗53:01 | 91.98 | |||

| HLA-C∗03:03 | 22.67 | |||

| HLA-C∗12:03 | 107.28 | |||

|

| ||||

| DTVEISPFY | 251 | 259 | HLA-A∗25:01 | 219.57 |

| HLA-A∗26:01 | 2.97 | |||

| HLA-A∗29:02 | 28.64 | |||

| HLA-A∗68:01 | 41.47 | |||

| HLA-B∗35:01 | 269.44 | |||

|

| ||||

| YRFLEIANY | 275 | 283 | HLA-B∗27:05 | 183.15 |

| HLA-C∗06:02 | 157.29 | |||

| HLA-C∗07:01 | 169.97 | |||

| HLA-C∗07:02 | 281.69 | |||

| HLA-C∗12:03 | 252.46 | |||

| HLA-C∗14:02 | 290.98 | |||

|

| ||||

| VSYKNSYHF∗ | 335 | 343 | HLA-A∗23:01 | 26.91 |

| HLA-A∗24:02 | 283.17 | |||

| HLA-A∗32:01 | 256.64 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 45.93 | |||

| HLA-B∗57:01 | 69.13 | |||

| HLA-B∗58:01 | 18.43 | |||

| HLA-C∗03:03 | 254.73 | |||

| HLA-C∗12:03 | 111.22 | |||

| HLA-C∗15:02 | 261.59 | |||

|

| ||||

| YKNSYHFSL | 337 | 345 | HLA-B∗08:01 | 212.76 |

| HLA-B∗39:01 | 7.84 | |||

| HLA-C∗03:03 | 17.48 | |||

| HLA-C∗07:02 | 41.18 | |||

| HLA-C∗14:02 | 249.85 | |||

|

| ||||

| HVRSGDIEY | 390 | 398 | HLA-A∗29:02 | 250.74 |

| HLA-A∗30:01 | 43.1 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 199.81 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:02 | 295.16 | |||

| HLA-B∗35:01 | 9.19 | |||

|

| ||||

| MSHGLAEMY | 413 | 421 | HLA-A∗29:02 | 33.03 |

| HLA-A∗30:02 | 95.04 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 263.61 | |||

| HLA-B∗35:01 | 49.68 | |||

| HLA-B∗57:01 | 132.85 | |||

| HLA-B∗58:01 | 228.7 | |||

|

| ||||

| FAYDKIQAH | 470 | 478 | HLA-B∗35:01 | 56.25 |

| HLA-B∗46:01 | 189.03 | |||

| HLA-C∗03:03 | 5.42 | |||

| HLA-C∗12:03 | 9.1 | |||

| HLA-C∗14:02 | 231.14 | |||

|

| ||||

| YLLYEDYTF∗ | 622 | 630 | HLA-A∗02:01 | 215.94 |

| HLA-A∗02:06 | 77.51 | |||

| HLA-A∗23:01 | 31.7 | |||

| HLA-A∗24:02 | 237.46 | |||

| HLA-A∗29:02 | 60.11 | |||

| HLA-A∗32:01 | 132.77 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 163.87 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:02 | 48.14 | |||

| HLA-B∗35:01 | 62.28 | |||

|

| ||||

| VVMTAAAAV | 728 | 736 | HLA-A∗02:01 | 80.99 |

| HLA-A∗02:06 | 10.14 | |||

| HLA-A∗68:02 | 42.19 | |||

| HLA-C∗14:02 | 60.62 | |||

| HLA-C∗15:02 | 231.69 | |||

|

| ||||

| IASFLSNPF | 743 | 751 | HLA-A∗32:01 | 81.65 |

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 94.19 | |||

| HLA-B∗35:01 | 11.95 | |||

| HLA-B∗58:01 | 219.61 | |||

| HLA-C∗03:03 | 83.79 | |||

| HLA-C∗12:03 | 189.81 | |||

|

| ||||

| FLSNPFAAL | 746 | 754 | HLA-A∗02:01 | 16.28 |

| HLA-A∗02:06 | 8.88 | |||

| HLA-A∗68:02 | 172.75 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 128.57 | |||

| HLA-B∗15:02 | 136.86 | |||

| HLA-C∗03:03 | 3.25 | |||

| HLA-C∗12:03 | 140.95 | |||

| HLA-C∗14:02 | 85.38 | |||

|

| ||||

| KSNPVQVLF | 778 | 786 | HLA-A∗32:01 | 76.58 |

| HLA-B∗15:01 | 283.12 | |||

| HLA-B∗57:01 | 19.71 | |||

| HLA-B∗58:01 | 2.62 | |||

| HLA-C∗15:02 | 155.84 | |||

∗Proposed peptides.

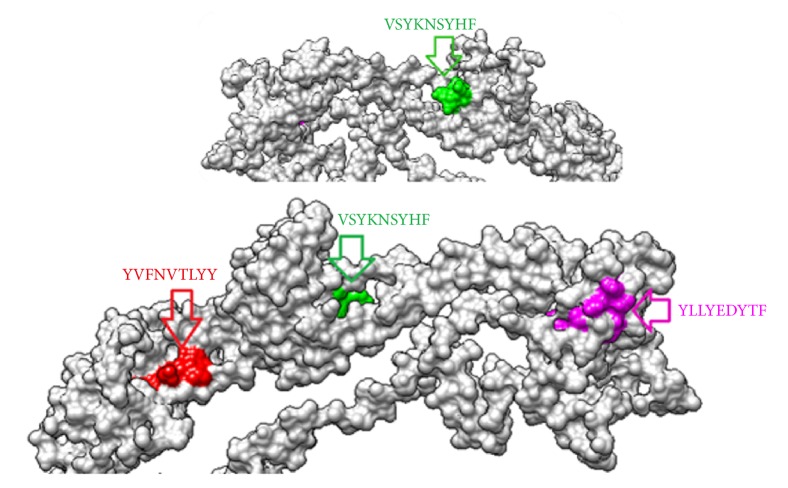

Figure 5.

The 3D structure of reference glycoprotein B of ILTV and the position of proposed cytotoxic T cell epitopes suggested to interact with MHC-I virus illustrated by UCSF-Chimera visualization tool.

3.4.2. Prediction of T Helper Cell Epitopes and Interaction with MHC Class II

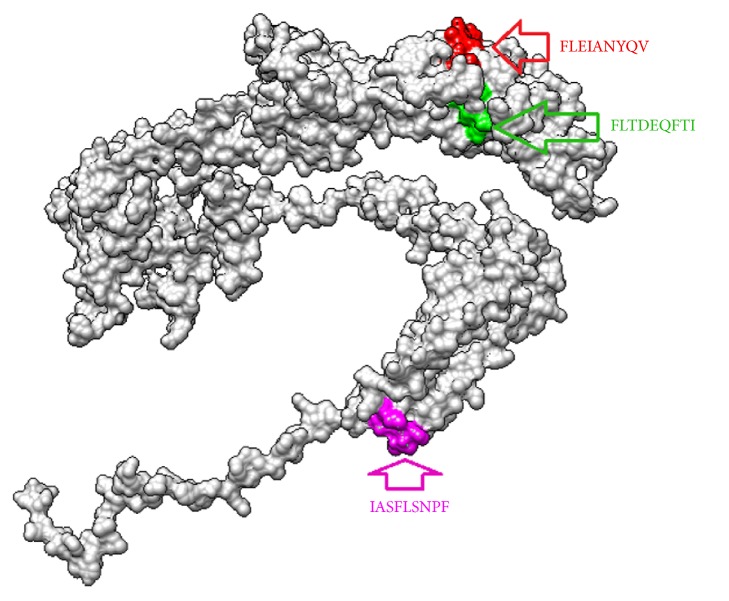

The reference strain of glycoprotein B was subjected to different analyzing methods using IEDB MHC-II binding prediction tool based on NN-align with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) ≤ 1000. The peptide (core) 301FLTDEQFTI309 exhibited high affinity to MHCII alleles due to great binding with 76 MHC-II alleles followed by 277FLEIANYQV285 and 743IASFLSNPF751 as they linked with 67 human alleles (Table 4 and Figure 6).

Table 4.

List of best six epitopes that bind with high affinity with the human MHC class II alleles.

| Core Sequence | Peptide Sequence | Start | End | Allele | IC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLRSTVSKA | LPLVPSLLRSTVSKA | 192 | 206 | HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 824.7 |

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 99.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 421.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 300.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 768.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 155.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 143.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 783.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 888.9 | ||||

| PLVPSLLRSTVSKAF | 193 | 207 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 436 | |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 538.2 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 413.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 42.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 123.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 185.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 166.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 478 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 103 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 394.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 774.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 978 | ||||

| LVPSLLRSTVSKAFH | 194 | 208 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 464.3 | |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 457.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 378.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 26.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 57.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 147.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 360 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 71.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 336.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗11:01 | 148.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 652.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 824.6 | ||||

| VPSLLRSTVSKAFHT | 195 | 209 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 682.2 | |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 397.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 18 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 32.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 108.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 303.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 52 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 219.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 568.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 745 | ||||

| PSLLRSTVSKAFHTT | 196 | 210 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 871.8 | |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 506.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 26.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 49.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 126.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 178.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 369.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 61.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 809.3 | ||||

| SLLRSTVSKAFHTTN | 197 | 211 | HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 609.2 | |

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 36.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 89.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 130.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 467.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 75.6 | ||||

| LLRSTVSKAFHTTNF | 198 | 212 | HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 836.1 | |

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 218.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 184.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 384.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 643.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 106 | ||||

|

| |||||

| FLEIANYQV | VYRDYRFLEIANYQV |

271 |

285 |

HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 9.1 |

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 752 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 288.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 67.4 | ||||

| YRDYRFLEIANYQVR |

272 |

286 |

HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 10.9 | |

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 565 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 237.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 29.8 | ||||

| RDYRFLEIANYQVRD | 273 | 287 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 284.1 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 90.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 8.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 41.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 15.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 585.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗11:01 | 54.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 216.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 875 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 27.2 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 218.5 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:01/DQB1∗05:01 | 637.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 331.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 81.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 32.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 273.4 | ||||

| DYRFLEIANYQVRDL | 274 | 288 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 475 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 72.5 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 42.9 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 294.4 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 462.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 8.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 58.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 39.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 15.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 704.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗11:01 | 43.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 190.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 979.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 18.3 | ||||

| RFLEIANYQVRDLET | 276 | 290 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 594 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 113.7 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 66 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 726.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 15.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 261.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 174.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 174.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 31 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 931.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗11:01 | 140.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 486.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 39 | ||||

| FLEIANYQVRDLETG | 277 | 291 | HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 336.8 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 146.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 28.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 273.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 325.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 57.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗11:01 | 340.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | 852.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 101.7 | ||||

|

| |||||

| FLTDEQFTI | PPKKRNFLTDEQFTI | 295 | 309 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 246.4 |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 35.5 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 93.6 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 541 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 506.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 76.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 198.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 274.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 98.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 4.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 948.8 | ||||

| PKKRNFLTDEQFTIG | 296 | 310 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 172.7 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 24.5 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 82.3 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 475.5 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 341.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 850.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 59.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 136.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 869.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 325 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 162 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 4.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 769 | ||||

| KKRNFLTDEQFTIGW | 297 | 311 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 123 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 20.1 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 66.4 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 394.6 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 199 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 342.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 37.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 103.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 805.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 330.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 203.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 4.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 527 | ||||

| KRNFLTDEQFTIGWD | 298 | 312 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 110.8 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 21.6 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 65 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 405.2 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 148.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 354.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 31.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 98.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 398.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 325.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 4.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 505.9 | ||||

| RNFLTDEQFTIGWDA | 299 | 313 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 115.3 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 26.7 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 88.5 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗05:01 | 532.9 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 182.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 687.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 64.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 178.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 700.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 5.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 948.3 | ||||

| NFLTDEQFTIGWDAM | 300 | 314 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 244 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 44.6 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 173.3 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 250.2 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗02:01 | 475.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 164.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 278.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 9 | ||||

| FLTDEQFTIGWDAME | 301 | 315 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 640 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 154.8 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 395.6 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 437.8 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗02:01 | 459.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 433.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 271.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 15.5 | ||||

|

| |||||

| LLGDIVAVS | QPVSARLLGDIVAVS | 519 | 533 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 922.5 |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 822.3 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 726 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 42.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 494.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 914.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 211.5 | ||||

| PVSARLLGDIVAVSK | 520 | 534 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 752.7 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 853.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 715.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 34 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 380.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 298 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 458.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 571.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 196.5 | ||||

| VSARLLGDIVAVSKC | 521 | 535 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 723.1 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 733.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 502.8 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 29.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 214.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 237 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 429.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 541.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 172.3 | ||||

| SARLLGDIVAVSKCI | 522 | 536 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 677.6 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 650.5 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 555.2 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 26.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 175.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 124.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 187.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 396.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 396.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 143.4 | ||||

| ARLLGDIVAVSKCIE | 523 | 537 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 791.2 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 787.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 590.2 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 31.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 270.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 199.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 255.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 643.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 360.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 379.2 | ||||

| RLLGDIVAVSKCIEI | 524 | 538 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 807.2 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 911.1 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 621.6 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 35.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 347.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 375.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 977.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 414.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 974.2 | ||||

| LLGDIVAVSKCIEIP | 525 | 539 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 941 | |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 748.6 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 37.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 688 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 848.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 521 | ||||

|

| |||||

| IASFLSNPF | ISTVSGIASFLSNPF | 737 | 751 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 264.9 |

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗02:01 | 384.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 53.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:04 | 92.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 16.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 25 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 104.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 24.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 103.5 | ||||

| STVSGIASFLSNPFA | 738 | 752 | HLA-DPA1∗01/DPB1∗04:01 | 559.3 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 320.6 | ||||

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 240.5 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:01/DQB1∗05:01 | 976.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗02:01 | 474.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 101.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 41.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 15.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 31.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 589.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 74.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 18.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 77.6 | ||||

| TVSGIASFLSNPFAA | 739 | 753 | HLA-DPA1∗01:03/DPB1∗02:01 | 179.9 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 219.5 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:01/DQB1∗05:01 | 915.8 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗02:01 | 611.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 40.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 27.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 15.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 44 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 538.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 72.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 15.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 57.1 | ||||

| VSGIASFLSNPFAAL | 740 | 754 | HLA-DQA1∗01:01/DQB1∗05:01 | 710 | |

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗02:01 | 755.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 14.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 427.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 22 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 14.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 43.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 486.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 52.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗11:01 | 377.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 12.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 29.4 | ||||

| SGIASFLSNPFAALG | 741 | 755 | HLA-DQA1∗01:01/DQB1∗05:01 | 936.1 | |

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 629.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 27.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 18 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗07:01 | 67.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 582.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 56.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 14.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 50.2 | ||||

| GIASFLSNPFAALGI | 742 | 756 | HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 27.1 | |

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 38.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 27.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 594.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗09:01 | 58.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 17.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 73.5 | ||||

| IASFLSNPFAALGIG | 743 | 757 | HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 67 | |

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 41.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | 28.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB4∗01:01 | 735.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB5∗01:01 | 119.8 | ||||

|

| |||||

| LLGDIVAVS | QPVSARLLGDIVAVS | 519 | 533 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 922.5 |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 822.3 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 726 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 42.2 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 494.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 914.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 211.5 | ||||

| PVSARLLGDIVAVSK | 520 | 534 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 752.7 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 853.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 715.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 34 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 380.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 298 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 458.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 571.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 196.5 | ||||

| VSARLLGDIVAVSKC | 521 | 535 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 723.1 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 733.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 502.8 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 29.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 214.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 237 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 429.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 541.8 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 172.3 | ||||

| SARLLGDIVAVSKCI | 522 | 536 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 677.6 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 650.5 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 555.2 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 26.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 175.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 124.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 187.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 396.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 396.7 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 143.4 | ||||

| ARLLGDIVAVSKCIE | 523 | 537 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 791.2 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 787.4 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 590.2 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 31.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01:01 | 270.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 199.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 255.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 643.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 360.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 379.2 | ||||

| RLLGDIVAVSKCIEI | 524 | 538 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 807.2 | |

| HLA-DPA1∗03:01/DPB1∗04:02 | 911.1 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 621.6 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 35.4 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 347.3 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 375.6 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:05 | 977.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 414.9 | ||||

| HLA-DRB3∗01:01 | 974.2 | ||||

| LLGDIVAVSKCIEIP | 525 | 539 | HLA-DPA1∗02:01/DPB1∗01:01 | 941 | |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02/DQB1∗06:02 | 748.6 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1∗05:01/DQB1∗03:01 | 37.1 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | 688 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗04:01 | 848.5 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1∗08:02 | 521 | ||||

∗Inhibitory concentration needed for binding MHC II to the IEDB NN-align method; the lower value is better.

Figure 6.

3D structure of reference glycoprotein B of ILTV and the position of proposed helper T cell epitopes suggested to interact with MHC-II virus illustrated by UCSF-Chimera visualization tool.

3.5. Overlapping of T Cell Epitopes Residues in MHC Classes I and II

Twelve epitopes from top five proposed MHC class I were associated with at least to 15 alleles from MHC class II epitopes (see Table 5). It was observed that top proposed epitope from MHCII (FLTDEQFTI), which achieved the highest linkages with 76 alleles from MHC class II, was linked with 3 alleles only from MHCI. While the second proposed epitopes (FLEIANYQV and IASFLSNPF) that bound to 67 MHCII alleles were associated with 2 and 6 alleles from MHC1, respectively. However, of these top epitopes, only four of top MHC1 epitopes and two of best epitopes from MHCII were not linked to any alleles from MHCII and MHCI, respectively.

Table 5.

Comparison between the numbers of alleles linked with top proposed epitopes in MHCI and MHCII.

| Peptide | MHCI | MHCII |

|---|---|---|

| MLICVCVAI | 5 | 0 |

| YVFNVTLYY | 12∗ | 49 |

| LYYKHITTV | 6 | 21 |

| TTVTTWALF | 6 | 16 |

| MATGDTVEI | 6 | 0 |

| DTVEISPFY | 5 | 5 |

| YRFLEIANY | 6 | 49 |

| VSYKNSYHF | 9∗ | 15 |

| YKNSYHFSL | 5 | 45 |

| HVRSGDIEY | 5 | 0 |

| MSHGLAEMY | 6 | 22 |

| VVMTAAAAV | 5 | 42 |

| FAYDKIQAH | 5 | 49 |

| YLLYEDYTF | 9∗ | 48 |

| IASFLSNPF | 6 | 67# |

| FLSNPFAAL | 8 | 58 |

| KSNPVQVLF | 5 | 0 |

| LLGDIVAVS | 0 | 60 |

| FLTDEQFTI | 3 | 76# |

| FLEIANYQV | 2 | 67# |

| LLRSTVSKA | 0 | 64 |

∗Proposed MHCI docked epitopes; #top proposed MHCII epitopes.

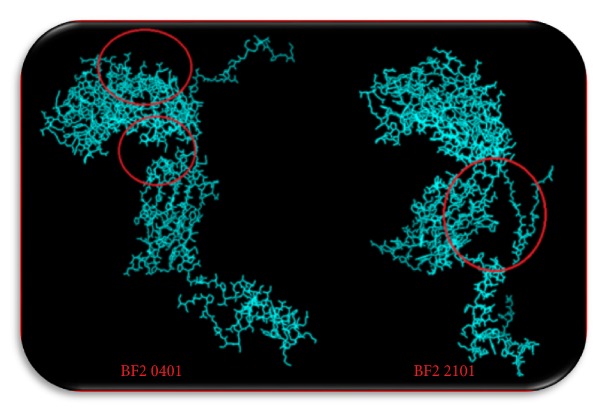

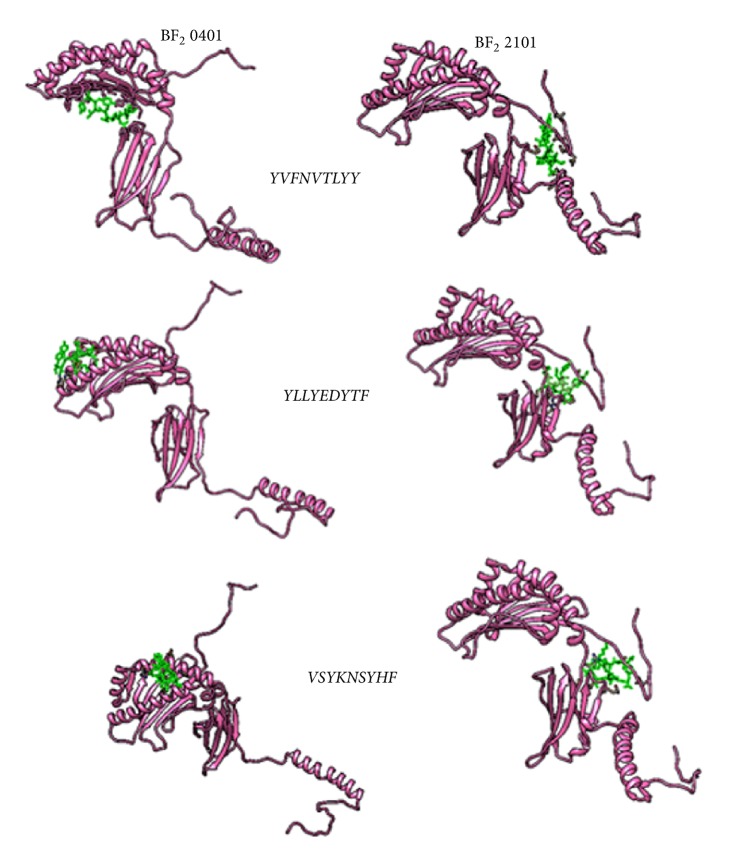

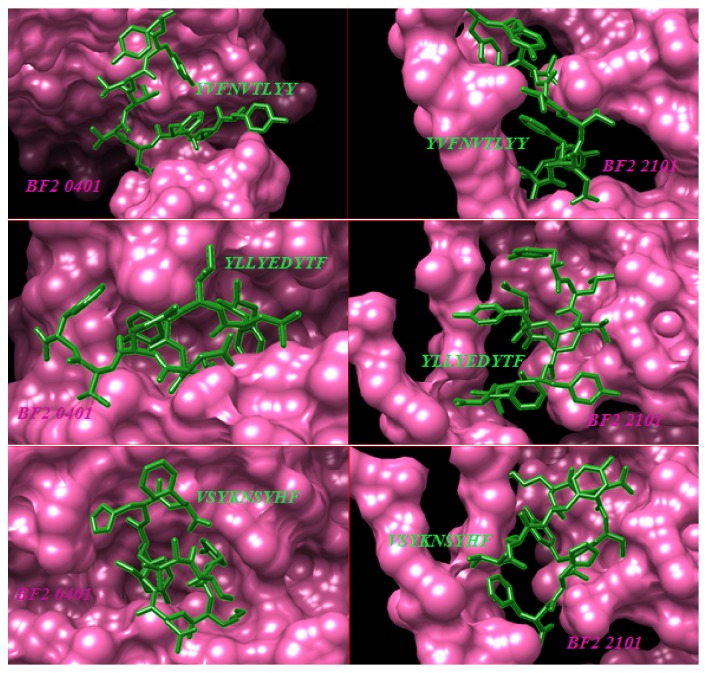

3.6. Molecular Docking of B-F Alleles and Predicted CTL Epitopes

The top ranked CTL proposed epitopes were selected for molecular docking to predict and symbolize the image of real CTL epitopes interaction with chicken alleles. For this purpose, two types of chicken BF alleles (BF2∗2101; BF2∗0401) were selected. The docked epitopes (301FLTDEQFTI309, 277FLEIANYQV285, and 743IASFLSNPF751) using peptide-binding groove affinity were used to evaluate the ability of predicted epitopes to bind with chicken BF alleles/receptors to chicken alleles BF2 (BF2∗2101 and BF2∗0401). Results indicated that the docked epitopes achieved strong binding affinity to Chicken BF2 alleles based on global energy and attractive VDW in kcal/mol unit. The lowest binding energy (kcal/mol) was selected to predict probable CTL epitopes. Docked ligand epitopes (118YVFNVTLYY126, 622YLLYEDYTF630, and 335VSYKNSYHF343) with BF2 2101 alleles (receptor) showed higher binding affinity which expressed by the lower global energy (-91.78, -89.53, and -66.41, respectively). However, BF 2 0401 allele as a receptor produced less binding affinity with docked ligands (-45.65, -51.56, and -61.68, respectively). These results indicated that the binding affinity of ligands is higher with the receptor BF2∗2101 allele compared with the other allele (BF2 0401) which produced less binding affinity. In addition, the docked molecules showed different groove binding site for both BF alleles. Figure 7 presents the 3D structure of chicken BF2 alleles and the proposed binding sites of docked epitopes. The binding energy scores in both BF2 alleles for the suggested epitopes using Patch Dock server for molecular docking are shown in Table 6. The visualization of the binding interactions between chicken BF2 receptor and MHCI epitopes in the structural level was performed using UCSF-Chimera visualization tool 1.8 (see Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 7.

The 3D structure of BF2 alleles of chicken using Chimera visualization tool. Red circle indicated the binding site of epitopes.

Table 6.

The binding energy and attractive VDW scores for the suggested epitopes with chicken BF2 alleles using PatchDock server.

| Ligand | Receptor | Global energy kcal/mol | Attractive VDW kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

| YVFNVTLYY | BF2 2101 | -91.78 | -32.23 |

| BF2 0401 | - 45.65 | -27.43 | |

|

| |||

| YLLYEDYTF | BF2 2101 | -89.53 | -34.81 |

| BF2 0401 | -61.68 | -27.77 | |

|

| |||

| VSYKNSYHF | BF2 2101 | -66.41 | -28.95 |

| BF2 0401 | -51.56 | -30.71 | |

Figure 8.

Visualization of PatchDock Molecular docking of MHC-I proposed epitopes and chicken BF2 alleles receptors using UCSF-Chimera visualization tool. Receptors (BF alleles) are represented by pink colour while CTL epitopes are represented by green one.

Figure 9.

Visualization of PatchDock Molecular docking of MHCI proposed epitopes and chicken BF2 alleles receptors using UCSF-Chimera visualization tool. Receptors (BF alleles) are represented by rounded ribbon structure hot pink colour while CTL epitopes are represented by green one.

4. Conclusion

Smart computational techniques which provide tremendous predictive and analytical information facilitate the prediction of novel epitopes that may act as a powerful vaccine through immunoinformatic technology.

This is the first in silico study to design peptide vaccine against avian ILTV through humoral and cell mediated immune responses. The expected epitopes in this study could help in prevention of latent infection caused by the use of attenuated vaccines and developing more effective and trustable prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines than conventional methods.

In this study new epitopes were proposed as promising multiepitopes vaccine for ILTV. CTL epitopes were selected as vaccine candidates due to their high binding affinity with different alleles. The result should be supported by designing the peptide vaccine in the lab and through clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff members of College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Bahri, Sudan, for their cooperation and support.

Data Availability

The sequences of envelope glycoprotein B (GB) of ILTV were retrieved from GenBank of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein) in August 2017. Retrieved strains and their accession numbers and geographical regions were listed in Table 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Menendez K. R., García M., Spatz S., Tablante N. L. Molecular epidemiology of infectious laryngotracheitis: a review. Avian Pathology. 2014;43(2):108–117. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2014.886004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hidalgo H. Infectious laryngotracheitis: a review. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola. 2003;5(3):157–168. doi: 10.1590/S1516-635X2003000300001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagust T. J., Jones R. C., Guy J. S. Avian infectious laryngotracheitis. Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'OIE. 2000;19(2):483–492. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.2.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldoni I., Rodríguez-Avila A., Riblet S., García M. Characterization of infectious laryngotracheitis virus (ILTV) isolates from commercial poultry by polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) Avian Diseases. 2008;52(1):59–63. doi: 10.1637/8054-070607-Reg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parra S., Nuñez L., Ferreira A. Epidemiology of avian infectious laryngotracheitis with special focus to south america: an update. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola. 2016;18(4):551–562. doi: 10.1590/1806-9061-2016-0224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreno A., Piccirillo A., Mondin A., Morandini E., Gavazzi L., Cordioli P. Epidemic of infectious laryngotracheitis in Italy: Characterization of virus isolates by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism and sequence analysis. Avian Diseases. 2010;54(4):1172–1177. doi: 10.1637/9398-051910-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han M. G., Kim S. J. Analysis of Korean strains of infectious laryngotracheitis virus by nucleotide sequences and restriction fragment length polymorphism. Veterinary Microbiology. 2001;83(4):321–331. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(01)00423-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller L. H., Benson C. E., Davison S., Eckroade R. J. Differences among restriction endonuclease DNA fingerprints of Pennsylvania field isolates, vaccine strains, and challenge strains of infectious laryngotracheitis virus. Avian Diseases. 1992;36(3):575–581. doi: 10.2307/1591751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan F. T. A review of the literature on infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) Avian Diseases. 1966;10(1):1–26. doi: 10.2307/1588203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufour-Zavala L. Epizootiology of infectious laryngotracheitis and presentation of an industry control program. Avian Diseases. 2008;52(1):1–7. doi: 10.1637/8018-051007-Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu haraz A. H., Abd elrahman K. A., Ibrahim M. S., et al. Multi epitope peptide vaccine prediction against sudan ebola virus using immuno-informatics approaches. Advanced Techniques in Biology & Medicine. 2017;5(203):2379–1764. doi: 10.4172/2379-1764.1000203.1000203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abd Albagi S. O., Hashim Ahmed O., Gumaa M. A., Abd elrahman K. A., Abu Haraz A. H., Hassan M. A. Immunoinformatics-peptide driven vaccine and in silico modeling for duvenhage rabies virus glycoprotein G. Journal of Clinical & Cellular Immunology. 2017;8(517):p. 2. doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awad Elkareem M. A., Ahmed Osman S., Mohamed H. A., et al. Prediction and conservancy analysis of multiepitope based peptide vaccine against merkel cell polyomavirus: an immunoinformatics approach. Immunome Research. 2017;13(134):p. 2. doi: 10.4172/1745-7580.1000134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shawan M. M., Mahmud H. A., Hasan M. M., Parvin A., Rahman M. N., Rahman S. M. In silico modeling and immunoinformatics probing disclose the epitope based peptidevaccine against zika virus envelope glycoprotein. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biological Research. 2014;2(4) doi: 10.30750/ijpbr.2.4.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reche P. A., Fernandez-Caldas E., Flower D. R., Fridkis-Hareli M., Hoshino Y. Peptide-based immunotherapeutics and vaccines. Journal of Immunology Research. 2014;2014:2. doi: 10.1155/2014/256784.256784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flower D. R. Designing immunogenic peptides. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;9(12):749–753. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bande F., Arshad S. S., Hair Bejo M., Kadkhodaei S., Omar A. R. Prediction and in silico identification of novel B-cells and T-cells epitopes in the S1-spike glycoprotein of M41 and CR88 (793/B) infectious bronchitis virus serotypes for application in peptide vaccines. Advances in Bioinformatics. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5484972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng J., Lin X., Wang X., et al. In silico analysis of epitope-based vaccine candidates against hepatitis B virus polymerase protein. Viruses. 2017;9(5):p. 112. doi: 10.3390/v9050112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., et al. Phylogeny. fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36(supplement 2):W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall T. BioEdit: an important software for molecular biology. Gerf Bulletin of Bioscience. 2011;2(1):60–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vita R., Overton J. A., Greenbaum J. A., et al. The immune epitope database (IEDB) 3.0. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:D405–D412. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen J. E., Lund O., Nielsen M. Improved method for predicting linear B-cell epitopes. Immunome Research. 2006;2(1):p. 2. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emini E. A., Hughes J. V., Perlow D. S., Boger J. Induction of hepatitis A virus-neutralizing antibody by a virus-specific synthetic peptide. Journal of Virology. 1985;55(3):836–839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.836-839.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolaskar A. S., Tongaonkar P. C. A semi-empirical method for prediction of antigenic determinants on protein antigens. FEBS Letters. 1990;276(1-2):172–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80535-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundegaard C., Lund O., Nielsen M. Accurate approximation method for prediction of class I MHC affinities for peptides of length 8, 10 and 11 using prediction tools trained on 9mers. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(11):1397–1398. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdelbagi M., Hassan T., Shihabeldin M., et al. Immunoinformatics prediction of peptide-based vaccine against african horse sickness virus. Immunome Research. 2017;13(135):p. 2. doi: 10.4172/1745-7580.1000135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patronov A., Doytchinova I. T-cell epitope vaccine design by immunoinformatics. Open Biology. 2013;3:p. 1. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120139.120139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen M., Lund O. NN-align. An artificial neural network-based alignment algorithm for MHC class II peptide binding prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10, article 296 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan W. M. User’s manual for Chimera grid tools, version 1.8. NASA Ames Research Center, 2003, http://people.nas.nasa.gov/~rogers/cgt/doc/man.html.

- 30.Källberg M., Wang H. P., Wang S. Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nature Protocols. 2012;7(8):1511–1522. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng J., Xu J. Raptorx: Exploiting structure information for protein alignment by statistical inference. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2011;79(S10):161–171. doi: 10.1002/prot.23175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng J., Xu J. A multiple-template approach to protein threading. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2011;79(6):1930–1939. doi: 10.1002/prot.23016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maupetit J., Derreumaux P., Tufféry P. A fast method for large-scale de novo peptide and miniprotein structure prediction. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2010;31(4):726–738. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beaufays J., Lins L., Thomas A., Brasseur R. In silico predictions of 3D structures of linear and cyclic peptides with natural and non-proteinogenic residues. Journal of Peptide Science. 2012;18(1):17–24. doi: 10.1002/psc.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen Y., Maupetit J., Derreumaux P., Tufféry P. Improved PEP-FOLD approach for peptide and miniprotein structure prediction. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2014;10(10):4745–4758. doi: 10.1021/ct500592m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duhovny D., Nussinov R., Wolfson H. J. Efficient unbound docking of rigid molecules. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics; 2002; Springer; [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneidman-Duhovny D., Inbar Y., Nussinov R., Wolfson H. J. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(supplement 2):W363–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrusier N., Nussinov R., Wolfson H. J. FireDock: Fast interaction refinement in molecular docking. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 2007;69(1):139–159. doi: 10.1002/prot.21495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osman M. M., Elamin E. E., Al-Nour M., et al. In silico design of epitope based peptide vaccine against virulent strains of hn-newcastle disease virus (NDV) in poultry species. IJMCR: International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Current Research. 2016;4 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ingale A. In silico homology modeling and epitope prediction of nucleocapsid protein region from japanese encephalitis virus. Journal of Computer Science & Systems Biology. 2010;3(2):53–58. doi: 10.4172/jcsb.1000056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ingale A. G., Goto S. Prediction of CTL epitope, in silico modeling and functional analysis of cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) protein of Campylobacter jejuni. BMC Research Notes. 2014;7(1, article 92) doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abro S. H., Ullman K., Belák S., Baule C. Bioinformatics and evolutionary insight on the spike glycoprotein gene of QX-like and Massachusetts strains of infectious bronchitis virus. Virology Journal. 2012;9, article 211 doi: 10.1186/1743-422x-9-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koch M., Camp S., Collen T., et al. Structures of an MHC class I molecule from B21 chickens illustrate promiscuous peptide binding. Immunity. 2007;27(6):885–899. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pourseif M. M., Moghaddam G., Naghili B., et al. A novel in silico minigene vaccine based on CD4 + T-helper and B-cell epitopes of EG95 isolates for vaccination against cystic echinococcosis. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 2018;72:150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vainio O., Koch C., Toivanen A. B-L antigens (class II) of the chicken major histocompatibility complex control T-B cell interaction. Immunogenetics. 1984;19(2):131–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00387856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hála K., Boyd R., Wick G. Chicken major histocompatibility complex and disease. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 1981;14(6):607–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1981.tb00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences of envelope glycoprotein B (GB) of ILTV were retrieved from GenBank of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein) in August 2017. Retrieved strains and their accession numbers and geographical regions were listed in Table 1.