Significance Statement

Although glomerular endothelial dysfunction and neoangiogenesis have long been implicated as factors contributing to diabetic kidney disease (DKD) pathophysiology, the molecular basis of these processes is not well understood. The authors previously found that a proangiogenic gene encoding leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1) was upregulated in isolated glomerular endothelial cells from diabetic mice. In this work, they demonstrate in a diabetic mouse model that LRG1 is a novel angiogenic factor that drives DKD pathogenesis through potentiation of endothelial TGF-β/activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) signaling. They also show that plasma LRG1 is associated with renal outcome in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes. These findings indicate that LRG1 has a pivotal role in DKD pathogenesis through TGF-β/ALK1 signaling and is a risk factor for disease progression.

Keywords: glomerular endothelial cells, TGF-beta, diabetic nephropathy, proteinuria

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Glomerular endothelial dysfunction and neoangiogenesis have long been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). However, the specific molecular pathways contributing to these processes in the early stages of DKD are not well understood. Our recent transcriptomic profiling of glomerular endothelial cells identified a number of proangiogenic genes that were upregulated in diabetic mice, including leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1). LRG1 was previously shown to promote neovascularization in mouse models of ocular disease by potentiating endothelial TGF-β/activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) signaling. However, LRG1’s role in the kidney, particularly in the setting of DKD, has been unclear.

Methods

We analyzed expression of LRG1 mRNA in glomeruli of diabetic kidneys and assessed its localization by RNA in situ hybridization. We examined the effects of genetic ablation of Lrg1 on DKD progression in unilaterally nephrectomized, streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice at 12 and 20 weeks after diabetes induction. We also assessed whether plasma LRG1 was associated with renal outcome in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Results

LRG1 localized predominantly to glomerular endothelial cells, and its expression was elevated in the diabetic kidneys. LRG1 ablation markedly attenuated diabetes-induced glomerular angiogenesis, podocyte loss, and the development of diabetic glomerulopathy. These improvements were associated with reduced ALK1-Smad1/5/8 activation in glomeruli of diabetic mice. Moreover, increased plasma LRG1 was associated with worse renal outcome in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Conclusions

These findings identify LRG1 as a potential novel pathogenic mediator of diabetic glomerular neoangiogenesis and a risk factor in DKD progression.

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a frequent complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) and the most common cause of ESRD in the United States.1 Intensive glycemic control, BP control, and blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system are the gold standard for current treatment of patients with DKD.2–4 However, these established regimens provide only partial therapeutic effects,5 indicating that pathogenic mechanisms driving DKD progression may not be targeted by current treatments. In addition, several recent clinical trials in DKD treatments were unsuccessful,5–8 highlighting an unmet need for better understanding of mechanisms mediating the early stages of DKD for the design of novel preventive therapeutic strategies.

Glomerular neoangiogenesis has long been implicated as contributing to the morphology and pathophysiology of DKD,9–11 and dysregulated expression of various endothelial growth factors are implicated in DKD pathogenesis.12 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A is thought to contribute to the initial hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria,13 such that blockade of VEGF signaling by pan-VEGF receptor inhibitor ameliorates diabetic albuminuria in mice.14 Imbalance of angiopoietin 1 (Ang-1) and angiopoietin 2 (Ang-2), another family of vascular growth factors necessary for the normal functioning of the glomerular filtration barrier, is also implicated in altered permeability in DKD.15–17 In addition to vascular growth factors, several other mechanisms of early glomerular endothelial cell (GEC) injury are implicated in DKD pathogenesis, such as decreased nitric oxide availability18–20 and disturbances in endothelial barrier.21,22 These studies suggest that endothelial dysfunction is among the earliest functional changes in diabetic kidneys. Indeed, a study by Weil et al.23 indicated that GEC injury precedes podocyte foot process effacement and microalbuminuria in Pima Indians with type 2 diabetes.

To assess the molecular changes associated with GEC injury in early DKD, we recently performed transcriptomic profiling of isolated GECs from streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice with endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) deficiency.24 Analysis of differentially expressed genes indeed indicated that angiogenesis and endothelial proliferation pathways were significantly upregulated in GECs of diabetic mice,24 and that leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1) was among the top upregulated genes. LRG1 is a secreted glycoprotein belonging to the leucine-rich repeat protein family,25 whose expression is increased in plasma and urine of patients with a variety of cancer malignancies and is thought to contribute to tumor-growth by promoting angiogenesis.26–29 Notably, a recent finding by Wang et al.30 demonstrated that LRG1 mediates the proangiogenic effects through enhancement of TGF-β1/ALK1-mediated signaling in murine models of ocular disease.

TGF-β regulates many aspects of endothelial functions including cell proliferation in early diabetic kidneys resulting in glomerular hypertrophy, but also the induction of apoptosis in microvascular endothelial cells.31 These contrasting actions of TGF-β on endothelial cells (ECs) are regulated by differential activation of two type 1 receptors: the ubiquitously expressed ALK5 and predominantly EC-restricted ALK1 receptors. ALK5 activation induces the Smad2/3 activation to block EC proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis; in contrast, ALK1 activation induces the Smad1/5/8 activation to promote EC proliferation, migration, and tube formation, resulting in neoangiogenesis.32–36 However, the role of ALK1 in glomerular angiogenesis has not been fully explored. The importance of the TGF-β–induced ALK1 pathway in driving the DKD pathogenesis was shown in our recent report on BMP and Activin Membrane-Bound Inhibitor (BAMBI), a TGF-β pseudoreceptor that represses TGF-β signaling.37 Genetic loss of Bambi significantly worsened diabetic glomerulopathy in relatively DKD-resistant C57BL/6 mice, which was associated with increased ALK1-mediated TGF-β signaling. In an opposite manner to BAMBI, LRG1 was shown to potentiate the proangiogenic ALK1 pathway by recruitment of TGF-β accessory receptor endoglin (ENG).30 This led us to speculate that the function of LRG1 would promote diabetes-induced glomerular angiogenesis via ALK1-induced signal transduction in GECs. Therefore, in this study, we examined the role of LRG1 in diabetic glomerular injury.

Methods

Study Approval

All mouse studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (ISMMS) and were performed in accordance with its guidelines.

Mouse Models

Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility with free access to chow and water and a 12-hour day/night cycle. Lrg1−/− mouse strain in C57BL/6J background was obtained from the Knock-Out Mouse Project Repository (#VG10067; www.komp.org). Flk1-H2B-EYFP (EYFP) mice in the C57BL/6J background38 were a generous gift from Dr. Margaret Baron (ISMMS). Diabetes was induced with intraperitoneal injections of STZ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for five consecutive days (50 μg/g body wt per day). To accelerate diabetic nephropathy, unilateral right nephrectomy was performed, as described,39 3 weeks before STZ injection. Body weight and fasting blood glucose levels were monitored biweekly. Diabetes was confirmed by fasting blood glucose level >300 mg/dl. The age- and sex-matched littermates injected with citrate vehicle served as nondiabetic controls. BP was measured using the noninvasive tail-cuff BP system (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). All mice were euthanized at either 12 or 20 weeks post-STZ or -vehicle injection.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as mean±SD. For comparisons of means between two groups, two-tailed, unpaired t tests were performed. For comparison of means between three or more groups, ANOVA with Tukey post-test was applied. Statistical significance was considered as P<0.05. Prism software v.6 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analyses.

Clinical Cohort and Analyses

The BioMe Biobank Program of The Charles Bronfman Institute for Personalized Medicine started in 2007 at the ISMMS.40,41 We randomly selected 997 BioMe participants with type 2 diabetes, a baseline eGFR between 45 and 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at the time of BioMe enrollment, and at least 3 years of follow-up data in the electronic health record. We defined the baseline period as 1 year before the BioMe enrollment date. We determined baseline and all follow-up eGFR values using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine equation,42 calculated median values per 3-month period of follow-up and utilized these for covariate and outcome ascertainment. We calculated follow-up time from BioMe enrollment date to the latest visit in the electronic health record.

LRG1 Measurements

Plasma samples were taken at the time of BioMe enrollment and stored at −80°C were used to derive the baseline biomarker measures. Plasma concentrations of LRG1 were measured via ELISA (#27769; IBL America, Minneapolis, MN). The lower limit of detection was 0.17 ng/ml, and the intra-assay coefficient of variation for the quality control samples was 6.03%, and the interassay coefficient of variation on 5% of samples run in duplicate was 6.3%. The laboratory personnel performing the biomarker assays were blinded to clinical information about the participants.

Outcomes

We defined the primary outcome as a composite of ESRD via linkage to the US Renal Data System or a sustained 40% decline in eGFR (confirmed decline on two or more separate 3-month intervals) over the follow-up period.

Statistical Analyses

The association of LRG1 with the composite renal end point was evaluated both continuously (log base 2–transformed) and by tertile. We utilized Cox regression with a time-to-event analysis where the composite renal outcome occurring any time during the follow-up period was counted as an event, and otherwise counted as a nonevent. We computed the time to event as the time to first dialysis/transplant for ESRD or the time to the first episode of 40% sustained eGFR decline. For participants without an event, the follow-up time was computed until the end of follow-up. A sequential adjustment was used to assess the independent association of the biomarkers with the composite endpoint. The area under the receiver operative curves was constructed to assess the discrimination for clinical variables versus clinical variables plus LRG1 at a timepoint of 4.5 years (chosen to coincide with the median follow-up of 4.5 years). The base clinical model consisted of age, sex, baseline eGFR, mean arterial pressure, hemoglobin A1C, hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, body mass index, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Additional methods used for the study are included in the Supplemental Methods.

Results

Expression of LRG1 Is Increased in Mouse and Human Diabetic Kidneys

Our recent transcriptomic profiling of isolated GECs24 indicated that Lrg1 was one of the highly expressed genes in STZ-induced diabetic eNOS-deficient (eNOS−/−) mice when compared with control eNOS−/− mice (Figure 1A). Our previous transcriptomic analysis of isolated glomeruli and podocytes from the same diabetic mouse model43 indicated that although Lrg1 is increased in the glomeruli, no difference was detected in isolated podocytes (Supplemental Figure 1A). Notably, consistent with the EC-restricted expression of ALK1 receptor, the transcriptomic data further confirmed high expression of Alk1 mRNA in specifically in GECs, whereas much lower Alk5 expression was found in podocytes and GECs (Supplemental Figure 1B). Increased Lrg1 mRNA expression was similarly observed in isolated glomeruli of three other diabetic mouse models, namely STZ-induced diabetic DBA/2J, and db/db and eNOS−/−;db/db mice in C57BLKS background44 in the Nephroseq database (nephroseq.org) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

LRG1 expression is increased in glomeruli of mouse and human diabetic kidneys. (A) RNA-sequencing data of Lrg1 expression in isolated GECs of vehicle- or STZ-injected eNOS−/− mice (reproduced from Fu et al.24). Each sample represents isolated GECs pooled from three to four mice. RPKM, reads per kilobase million. (B) Levels of Lrg1 mRNA in isolated glomeruli of STZ-induced diabetic DBA/2J, and db/db and in eNOS−/− db/db mice in C57BLKS background compared with their respective nondiabetic controls from Nephroseq database (nephroseq.org). (C) In situ hybridization detecting Lrg1 mRNA (blue) and Pecam (CD31) mRNA (pink) in kidneys of diabetic OVE26 mice and wild-type control mice (FVB WT). Magnified view of the outlined glomeruli in the upper panel is shown in the lower panels. Arrows highlight examples of Lrg1 expression in renal tubules and arrowhead highlight examples of Lrg1 expression that colocalize with CD31 outside the tubules. Scale bars, 20 μm. (D) Semiquantitative scoring of Lrg1 mRNA colocalized with Pecam mRNA (n=3 mice per group, 20 gloms scored per mouse). (E) In situ hybridization of LRG1 mRNA (red) combined with CD31 immunofluorescence (green) on human kidney sections with nuclear counterstain. Glomeruli are outlined with dotted lines on upper panels, and magnified view of the box is shown in lower panels. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Semiquantitative scoring of LRG1 mRNA colocalized with CD31 (n=3 kidneys per group, 15 gloms scored per kidney).

We next determined the expression pattern of LRG1 mRNA in mouse and human control and diabetic kidneys by in situ RNA hybridization.45 For Lrg1 expression in diabetic mouse kidneys, we used kidney sections from another experimental model of type 1 DM, namely the OVE26 mouse model,46 to further corroborate the above transcriptomic findings. Mouse Lrg1 mRNA probe (blue) colocalized predominantly with CD31 mRNA probe (pink) in the glomeruli of control mouse kidneys, and its expression markedly increased in the glomeruli of OVE26 (Figure 1, C and D). Lrg1 signal was also detected in the tubulointerstitium in normal kidneys, which further increased in the diabetic kidneys (Figure 1C, arrows and arrowheads). However, overall Lrg1 expression was more prominent in the glomeruli than in the tubulointerstitium. In situ hybridization for LRG1 in human kidneys combined with immunostaining for CD31 showed colocalization of LRG1 mRNA (red) with CD31 immunostained cells (green) in the glomeruli (Figure 1, F and G), consistent with its high expression in GECs and its upregulation in DKD.

Genetic Deletion of LRG1 Attenuates Diabetes-Induced Albuminuria and Glomerulopathy

To determine the role of LRG1 in DKD, we examined the effects of LRG1 loss using the global Lrg1-null (Lrg1−/−) mice. Lrg1−/− mice were grossly normal, as reported previously.30 Ablation of LRG1 had no effect on kidney function when examined up to 9 months of age (data not shown). Because Lrg1−/− mice were in the relatively DKD-resistant C57BL/6J background, unilateral nephrectomy (UNx) was performed before diabetes induction to aggravate the ensuing diabetic kidney injury.47 As shown in Figure 2A, diabetes was induced by low-dose STZ injections in Lrg1−/− mice and in Lrg1+/+ littermate controls (+STZ) three weeks post-UNx. Citrate buffer vehicle-injected UNx mice served as nondiabetic controls (−STZ), and all mice were euthanized at 12 weeks post-DM induction. The extent of hyperglycemia, body weight loss, and BP were similar between diabetic Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice compared with nondiabetic mice (Figure 2B, Supplemental Figure 2A, and Supplemental Table 1). However, DM-induced kidney hypertrophy was observed only in diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice, as measured by kidney-to-body weight ratio (Figure 2C). Histologic analysis showed that the development of glomerular hypertrophy and mesangial expansion was significantly blunted in diabetic Lrg1−/− mice compared with diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice (Figure 2, D and E). The extent of albuminuria, as assessed by the albumin-to-creatinine ratio of spot-collected urine samples over 12 weeks duration and by 24-hour urine albumin excretion at 12 weeks post-DM, was markedly attenuated in diabetic Lrg1−/− mice compared with diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice (Figure 2, F and G). DM-induced podocyte foot process effacement and loss (as ascertained by podocyte marker p5748,49) were also reduced in diabetic Lrg1−/− mice (Figure 3, A–D). Together, these data indicate that the genetic deletion of LRG1 results in marked attenuation of diabetic glomerulopathy.

Figure 2.

LRG1 ablation protects against diabetic glomerulopathy. (A) Schematics of the experimental design. UNx was performed in 8-week-old Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice 3 weeks before injection of STZ or citrate buffer vehicle. Mice were euthanized at 12 weeks postinjection for analysis (n=6–8 mice per group). (B) Biweekly blood glucose measurements of control and diabetic mice. (C) Kidney-to-body weight (BW) ratio at 12 weeks post-DM induction. (D) Representative images of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained kidneys. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) Quantification of glomerular volume and mesangial matrix fraction per mouse (20–30 gloms counted per mouse, n=6 mice). (F) Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) over time (n=6 per group). (G) Twenty four-hour urinary albumin excretion (UAE) at 12 weeks postinjection (n=6 mice per group). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001 versus respective nondiabetic controls; #P<0.05; ##P<0.01; and ###P<0.001 versus diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice.

Figure 3.

LRG1 ablation reduces podocyte foot process effacement. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy images of mouse glomeruli. Red arrowheads highlight effaced podocyte foot processes. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Quantification of average podocyte foot process width per mouse (n=5–6 mice per group, 10–20 fields analyzed per mouse). (C) Representative images of p57 immunofluorescence. Glomeruli are outlined with dotted white lines. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Quantification of number of p57-positive podocytes per mouse (n=5 mice per group, 20–30 gloms scored per mouse). ***P<0.001 versus nondiabetic control; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 versus diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice.

LRG1 Deletion Attenuates Diabetes-Induced Angiogenesis

As LRG1 was previously shown to be proangiogenic in the retinal vasculature,30 we next examined whether LRG1 ablation would alter the DM-induced angiogenesis in vivo. Directed in vivo angiogenesis assay50,51 was performed by implanting the angioreactors filled with basement membrane extracts subcutaneously in mice at 7 weeks post-DM. The vascularization within the angioreactors was analyzed after 14 days (Figure 4A). As anticipated, there was a marked increase in vascularization into the angioreactors in diabetic mice compared with nondiabetic controls (Figure 4B). However, this response was attenuated in diabetic Lrg1−/− mice when compared with diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice. Consistent with this finding, there was an increased CD31-positive immunofluorescence area in glomeruli of diabetic mice, which was also attenuated in diabetic Lrg1−/− kidneys at 12 weeks post-DM (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

LRG1 ablation attenuates angiogenesis in vivo. (A) Schematics of the experimental design. UNx was performed in 8-week-old Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice 3 weeks before injection of either low doses of STZ or citrate buffer vehicle. Directed in vivo angiogenesis assay (DIVAA) was performed at 7 weeks postinjection, and implanted angioreactors were taken out after 2 weeks (n=6 mice per group). (B) Images of angioreactors 14 days postimplantation. Positive control (Pos.) angioreactor was supplemented with FGF and VEGF, negative control (Neg.) was supplemented with no factors, and all others were supplemented with FGF alone. Quantification of FITC-lectin bound dissociated cells from angioreactors is shown on the right. (C) Representative CD31 immunofluorescence images and quantification of CD31-positive glomerular area per mouse (n=5 mice per group, 20–30 glomeruli per mouse). (D) Two-photon microscopy imaging and quantification of glomerular EYFP-positive cells in Lrg1+/+;EYFP and Lrg1−/−;EYFP mice (n=3 mouse, ten sections per mouse). (E) Representative 8-oxo-dG/CD31 immunofluorescence images and quantification of 8-oxo-dG glomerular area per mouse (n=5 mice per group, 20–30 glomeruli per mouse). Scale bar, 20 μm. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 versus nondiabetic controls; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 versus diabetic Lrg1+/+.

To quantitate the change in the number of GECs in the context of LRG1 ablation in early diabetic kidneys, Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice were crossed with Flk1-H2B-EYFP transgenic mice,24,38 which expresses a nuclear-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) driven by Flk1 promoter. Diabetes was similarly induced with low-dose STZ injections 3 weeks after UNx in Lrg1+/+;Flk1-H2B-EYFP (Lrg1+/+;EYFP) and in Lrg1−/−;Flk1-H2B-EYFP (Lrg1−/−;EYFP) mice. Because the above directed in vivo angiogenesis assay results showed differential angiogenic potential when examined between 7–9 weeks post-STZ injection, Lrg1+/+;EYFP and Lrg1−/−;EYFP mice were sacrificed at 8 weeks post-DM, and the total number of EYFP+ cells per glomeruli were quantified in 500 μm optically cleared kidney sections49 by two-photon microscopy. Indeed, the number of EYFP+ cells in the diabetic Lrg1+/+;EYFP mouse glomeruli was found to be increased at 8 weeks post-DM, but this increase was mitigated in the diabetic Lrg1+/+;EYFP mouse glomeruli (Figure 4D, Supplemental Files 1–4). An increased number of Ki-67–positive cells was also observed in the glomeruli of diabetic Lrg1+/+mice at 12 weeks post-DM compared with those of diabetic Lrg1-/- mice (Supplemental Figure 2B).

As oxidative stress is a key component in DKD development,52 we next examined the extent of oxidative damage in by the detection of 8-oxo-2′deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG). The presence of 8-oxo-dG was markedly elevated in the glomeruli of diabetic mice compared with those of nondiabetic mice, which largely overlapped with CD31+ cells. However much less 8-oxo-dG were detected in the glomeruli of diabetic Lrg1−/− mice compared with diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice. Together, our data strongly indicate that LRG1 is a critical mediator of angiogenesis and endothelial injury in diabetic kidneys.

LRG1 Potentiates ALK1-Mediated Smad1/5/8 Activation in GECs

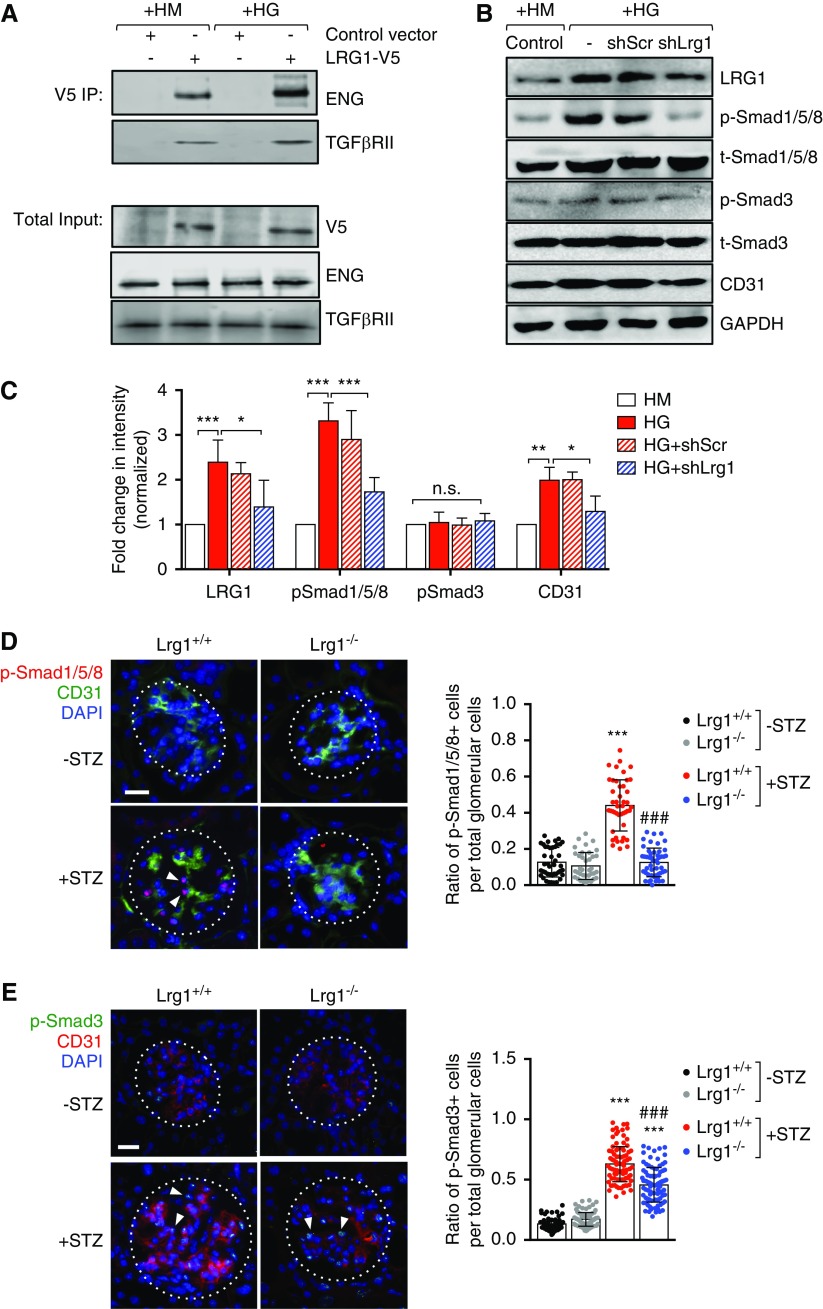

LRG1 was previously shown to promote TGF-β–induced ALK1-Smad1/5/8 signal transduction by recruitment of accessory TGF-β receptor ENG and TGF-β receptor type 2 (TβR-II) in brain endothelial cells and in HUVECs.30 To examine whether LRG1 similarly interacted with ENG and TβR-II in GECs, we transduced the immortalized murine GECs (mGECs)24 with the recombinant lentivirus expressing the control V5-tag or V5-tagged LRG1 (Supplemental Figure 3A). mGECs were then exposed to high-glucose (HG, 30 mM) or high-mannitol (HM, 25 mM mannitol and 5 mM glucose) culture conditions for 48 hours. Indeed, both ENG and TβR-II coimmunoprecipitated with V5-tagged LRG1 and these interactions appeared to increase in HG conditions (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

LRG1 potentiates the ALK1-Smad1/5/8 pathway in GECs in diabetic conditions. (A) Immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 antibody using lysates of conditionally immortalized mGECs transduced with pHR lentiviral vector (Control vector) or pHR expressing recombinant V5-tagged LRG1 (LRG1-V5) cultured under high mannitol (HM) or high glucose (HG) conditions for 48 hours. Recombinant LRG1 coimmunoprecipitates with endogenous ENG and TGF-β receptor type 2 (TβRII) in mGECs in both conditions. (B and C) Effects of Lrg1 knockdown was examined in mGECs transduced with pLKO lentiviral vector (−), pLKO vector expressing scrambled shRNA (shScr), or shRNA against LRG1 (shLrg1). Lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using primary antibodies as indicated. Representative western blot image (of triplicate experiments) is shown in (B) and densitometric analysis is shown in (C). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001 when compared between indicated groups by ANOVA with Tukey corrections. (D and E) Immunostaining of (D) phospho-Smad1/5/8 (p-Smad1/5/8) and CD31 or (E) phospho-Smad3 (p-Smad3) and CD31 on frozen kidney sections of Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice. The ratio of p-Smad1/5/8–positive or p-Smad3–positive cells per total glomerular cells per kidney section is shown on the right (n=3 mice, 15–20 sections scored per mouse). Scale bar, 20 μm. White arrowheads show examples of nuclear-localized p-Smad1/5/8 or p-Smad3. ***P<0.001 versus nondiabetic control; ###P<0.001 versus diabetic Lrg1+/+.

We recently showed that HG conditions induced the expression of LRG1 in mGECs and that the shRNA-mediated knockdown of Lrg1 attenuated the HG-induced increase in endothelial tube formation in vitro.24 Therefore, we next examined whether the suppression of LRG1 could impede the ALK1 signaling in GECs. mGECs stably transduced with recombinant lentivirus expressing shRNA against Lrg1 or scrambled control sequence (Supplemental Figure 3B) were exposed to HG or HM for 48 hours. HG-induced elevation of LRG1 expression in mGECs was associated with increased phospho-Smad1/5/8, but not phospho-Smad3 (Figure 5, B and C). Correspondingly, knockdown of Lrg1 markedly reduced phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 under HG conditions, without affecting the phosphorylation of Smad3. Consistent with the in vitro findings, Smad1/5/8 activation was markedly enhanced in the glomeruli of diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice, which largely colocalized with CD31 immunostaining (Figure 5D). However, very little phospho-Smad1/5/8 was detected in the glomeruli of diabetic Lrg1−/− mice (Figure 5D), indicating that the loss of LRG1 nearly abrogated the ALK1 signal transduction in GECs in the glomeruli of diabetic kidneys. In contrast, the activation of Smad3 detected in the glomeruli of diabetic mice was only modestly affected by the loss of LRG1 (Figure 5E). Taken together, our results indicate that LRG1 potentiates ALK1-mediated angiogenesis in the glomeruli in the diabetic kidneys, thereby promoting DKD progression.

Renoprotection Conferred by LRG1 Deletion Is Maintained at a Later Stage of DKD

As diabetes-induced glomerular neoangiogenesis is thought to occur in the early stages of DKD, we next examined the efficacy of long-term loss of LRG1 in a later stage of DKD and whether its ablation may have potentially detrimental consequences in the disease progression. Diabetes was induced similarly as above in UNx Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice (as well as in Lrg1+/+;EYFP and Lrg1−/−;EYFP mice) and the effects of LRG1 loss were examined after 20 weeks post-DM (Figure 6A). The extent of hyperglycemia, body weight loss, and kidney-to-body weight ratio compared with nondiabetic mice was similar between the diabetic Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice at 20 weeks post-DM (Supplemental Figure 4). Although a modest reduction in glomerular hypertrophy and mesangial expansion still persisted in diabetic Lrg1−/− mice as compared with diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice (Figure 6C), proteinuria and overall renal function, assessed by BUN measurement, showed a significant improvement in diabetic Lrg1−/− mice (Figure 6D). As expected, podocyte loss and effacement had worsened in the diabetic mice of both genotypes at 20 weeks post-DM compared with 12 weeks post-DM, but the ablation of LRG1 significantly reduced podocyte loss and injury (Figures 3 and 7, A and B). Similarly, DM-induced glomerular basement membrane thickening was reduced in diabetic Lrg1−/− mice (Figure 7A). Moreover, LRG1 ablation conferred protection against DM-induced oxidative damage, as assessed by detection of 8-oxo-dG (Figure 7C). Interestingly, when the total number of EYFP-positive GECs per glomeruli was calculated at 20 weeks post-DM, we found that the initial increase in GECs observed at 8 weeks post-DM (Figure 4D) was no longer observed at 20 weeks in diabetic Lrg1+/+;EYFP mice (Figures 4D and 7D, Supplemental Files 5 and 6), whereas this number appeared to be unaffected in diabetic Lrg1−/−;EYFP mice. Taken together, these data indicate that the ablation of LRG1 does not contribute to any unfavorable outcome, but confers long-term renoprotection against DKD.

Figure 6.

Renoprotection by LRG1 loss persists in the later stage of DKD. (A) Schematics of the experimental design. UNx was performed in 8-week-old Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice 3 weeks before injection of low doses of either STZ or citrate buffer vehicle. Mice were euthanized at 20 weeks postinjection for analysis (n=5–8 mice per group). (B) Representative image of kidneys stained with periodic acid–Schiff at low magnification (top panels; scale bar, 50 μm) and at high magnification (bottom panels; scale bar, 20 μm). (C) Quantification of glomerular volume and mesangial fraction at 20 weeks post-DM induction per mouse (n=6 mice per group, 20–30 gloms scored per mouse). (D) Renal function assessment at 20 weeks post-DM of 24-hour urinary albumin excretion (UAE) levels and BUN levels (n=5–8 mouse per group). ***P<0.001 versus respective nondiabetic controls; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 versus diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice.

Figure 7.

LRG1 loss confers protection against podocyte and endothelial cell injury at the later stage of DKD. (A) Transmission electron microscopy images of Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mouse kidneys at ×10,000 magnification (scale bar, 5 μm). Red arrowheads highlight the severe effacement of podocyte foot processes in the diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice. Quantification of average podocyte foot process widths (PFWs) and glomerular basement membrane (GBM) widths are shown on the right (n=3 mice per group, ten fields per mouse). (B) Representative images of p57 immunofluorescence and quantification per mouse (n=5 mice per group, 20–30 gloms scored per mouse). (C) Representative 8-oxo-dG and CD31 immunofluorescence images and quantification of 8-oxo-dG glomerular area per mouse. (D) Two-photon microscopy imaging and quantification of glomerular EYFP-positive cells in Lrg1+/+;EYFP and Lrg1−/−;EYFP mice (n=3 mouse, ten sections per mouse; Supplemental Files 5 and 6 show examples of the z-stacks). Scale bar, 20 μm. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 versus respective nondiabetic controls; ###P<0.001 versus diabetic Lrg1+/+ mice.

Plasma LRG1 as a Marker of DKD Progression in Humans

As LRG1 is a secreted glycoprotein elevated in human and mouse diabetic kidneys, we next examined whether plasma LRG1 levels in patients with DKD are associated with renal outcome. We measured LRG1 on plasma samples from a subcohort of 871 participants with type 2 diabetes in the BioMe Biobank Cohort at the ISMMS (Supplemental Figure 5). Supplemental Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of patients. Median age was 60 years, 507 (58.2%) were women, and median eGFR was 68.4 (interquartile range, 55.3–80.0) ml/min per 1.73 m2. Participants with higher LRG1 were older, more likely to be women, and more likely to have a history of congestive heart failure. Plasma LRG1 was not significantly correlated with eGFR (r=−0.02; P=NS) or albuminuria (r=0.06; P=NS) at baseline at the time of enrollment into the BioMe Biobank Program. Of the 871 patients analyzed, 121 (13.8%) experienced the composite end point, as defined by 40% sustained eGFR decline or ESRD during a median follow-up of 4.5 (interquartile range, 3.3–6.1) years. Notably, participants with the renal end point had higher levels of LRG1 (80.74 versus 53.79 ng/ml). The event rates for the composite renal end points of 40% sustained decline in eGFR or ESRD were 7.5% for the lowest tertile, 12.7% for the middle tertile, and 21.3% for the top tertile of LRG1 (Figure 8), which yielded an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.6 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.9 to 2.7) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.4) for the middle and top tertiles, respectively, versus the bottom tertile (Table 1). For each doubling in LRG1, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1 to 1.4). The area under the receiver operative curves for the composite kidney end point was 0.740 (95% CI, 0.69 to 0.79) for the clinical model and increased to 0.765 (95% CI, 0.72 to 0.82) with the addition of LRG1. Together, these results indicate that angiogenic molecule LRG1 is a risk factor for DKD progression.

Figure 8.

Plasma LRG1 is associated with renal outcome in patients with type 2 DM. Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by tertiles of plasma LRG1 for the composite renal outcome of sustained 40% decline in eGFR or ESRD.

Table 1.

Association of plasma LRG1 with the renal outcome

| LRG1, ng/ml | N | N (%) with outcome | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Continuous (per doubling) | 871 | 121 (13.9) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.5) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) |

| Tertiles | |||||

| ≤40.0 ng/ml | 290 | 22 (7.5) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| 40.1–78.0 ng/ml | 291 | 37 (12.7) | 1.8 (1.1 to 3.1) | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.9) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.7) |

| ≥78.1 ng/ml | 290 | 62 (21.3) | 3.0 (1.8 to 4.8) | 2.9 (1.7 to 4.7) | 2.7 (1.6 to 4.4) |

Model 1: unadjusted analysis; model 2: adjusted for age, sex, and baseline eGFR; model 3: model 2 plus hemoglobin A1C, hypertension, coronary disease, heart failure, baseline mean arterial pressure, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use, and urine albumin to creatinine ratio (available as a covariate in 608 of the 871 participants). HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

Our study highlights the role of LRG1 as a potential pathogenic mediator of glomerular neoangiogenesis through the activation of ALK1 signaling pathway. LRG1 expression is enriched in endothelial cells, particularly in GECs, and upregulated in diabetic kidneys. Although Lrg1 mRNA does not appear to be significantly expressed in podocytes, whether it is expressed in other glomerular cells to potentiate TGF-β signaling remains to be determined. In situ hybridization analysis showed that LRG1 expression was not limited to GECs in diabetic kidneys, but expressed in tubulointerstitial compartments. Thus, LRG1 is likely expressed in tubular epithelial and peritubular capillary endothelial cells in normal kidneys, as well as infiltrating immune cells in the diseased kidneys. Future studies utilizing tissue-specific Lrg1 knockout or overexpression mouse models are required to delineate the role of LRG1 in diabetic kidneys in a cell-specific manner.

Our previous24 and current work demonstrate that the expression of LRG1 is elevated in GECs in response to HG conditions in vitro, suggesting that hyperglycemia is one of the factors leading to its upregulation in diabetic kidneys. A recent study also showed that TNF-α induces LRG1 expression to promote angiogenesis and mesenchymal stem cell migration in the subchondral bone of osteoarthritis joints.53 In silico analysis of LRG1 promoter indeed indicated multiple potential binding sites for p65 NF-κB and STAT3 transcription factors. Thus, it is plausible that the inflammatory cytokines known to be involved in the progression of DKD, such as TNF-α and IL-6,54 may also participate in LRG1 upregulation in diabetic kidneys. In addition, miR-335 has been shown to target multiple genes in the noncanonical TGF-β pathway, including LRG1,55,56 and to inhibit HG-mediated apoptosis in osteoblasts.57 The suppression of miR-355 in diabetic conditions may be another factor contributing to elevated LRG1 expression in GECs. Future studies are required to elucidate the detailed mechanism of LRG1 upregulation in GECs of diabetic kidneys.

In this study, we have demonstrated that the genetic deletion of LRG1 significantly attenuated diabetic kidney injury and TGF-β/ALK1-induced angiogenesis in the experimental model of early DKD. The importance of ALK1-mediated TGF-β signaling in endothelial cells in diabetic kidneys is also supported by our previous study demonstrating that the genetic loss of BAMBI, a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling, resulted in significant augmentation of glomerular injury and proteinuria, which was associated with enhanced activation of ALK1 pathway in the glomeruli of diabetic mice.37 Together, our prior and current work demonstrate the key pathogenic role of glomerular TGF-β/ALK1 signaling in diabetic kidneys and suggest that the targeting of LRG1 could be a unique approach for inhibition of the specific TGF-β/ALK1 pathway to attenuate DKD progression. Indeed, total blockade of TGF-β signaling may not be effective and could be potentially hazardous, as it affects multiple pathways and systems through different receptors.58,59 Indeed, a recent clinical study of anti–TGF-β1 antibody blockade in patients with DKD failed to show beneficial effects when added to RAS blockade.60 Although this lack of treatment efficacy could be multifactorial, it further underscores the need for better understanding of TGF-β functions and their downstream signaling pathways in specific kidney cell types for the design of more targeted treatment strategies. Moreover, in contrast to ALK1 or ENG, whose haploinsufficiency is associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia,61 LRG1 deficiency in mice does not appear to result in major physiologic deficits.30 We did not observe any loss of renal function in nondiabetic mice when examined up to 9 months of age, and LRG1 deficiency persisted in conferring renoprotection in later-stage DKD at 20 weeks post-DM, making LRG1 an attractive target for anti-angiogenic therapy in DKD. However, the limitation of our study is that the mouse model utilized in this study is a global LRG1 knockout model, and as discussed above, LRG1 expression is not restricted to the endothelial cells. Thus, future studies using the endothelial-specific Lrg1 knockout or overexpression model would be required to confirm the endothelial phenotypes observed in this study.

As secreted glycoprotein, LRG1 levels have been shown to increase in the plasma and urine of patients with a variety of cancer malignancies26–29 and inflammatory diseases.62–65 Our findings in the BioMe cohort, consisting of mixed races of Western patients with diabetes, indicate that plasma LRG1 is associated with renal outcome. Of note, during the preparation of this report, similar findings regarding plasma LRG1 were reported in a T2DM patient cohort in Singapore by Liu et al.66 Thus, the prognostic role of LRG1 in DKD progression has been confirmed in two separate patient cohorts, further strengthening our observations and confirming the human relevance of LRG1 in the pathogenesis of DKD. Future studies are required to confirm the clinical implications of LRG1 and other angiogenesis factors in DKD, and to assess the efficacy of urinary LRG1 detection as a prognostic marker of DKD progression. In conclusion, our study demonstrates a pivotal role of proangiogenic molecule LRG1 in the pathogenesis of DKD, and suggests that LRG1 is not only a promising therapeutic target against DKD, but also a risk factor for disease progression.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Q.H., J.C.H., and K.L. designed the study. Q.H., L.Z., J.F., D.A.V., and Z.L. conducted the experiments. K.C., W.J., G.N.N., M.K., V.D.D., and S.G.C. acquired the data. Q.H., L.Z., D.A.V., G.-Y.C., X.-M.C., V.D.D., S.G.C., J.C.H., and K.L. analyzed the data. Q.H., L.Z., S.G.C., J.C.H., and K.L. drafted the manuscript. Q.H., L.Z., V.D.D., D.S., J.C.H., and K.L. revised the manuscript, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Q.H. is supported by the China Scholarship Council (grant no. 201503170082) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81870491), S.G.C. is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01DK096549, U01DK106962, U01DK082185, and R01HL085757; G.N.N. is supported by NIH grant K23DK107908; J.C.H. is supported by NIH grants R01DK078897, R01DK088541, R01DK109683, and P01DK56492, and VA merit award IBX000345C; and K.L. is supported by NIH grant R01DK117913-01.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2018060599/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. RNA-sequencing expression of mouse Lrg1 mRNA in isolated glomeruli, podocytes, or GECs.

Supplemental Figure 2. Additional characterization of diabetic and control Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice at 12 weeks post-DM.

Supplemental Figure 3. Overexpression and knockdown of LRG1 in mGECs.

Supplemental Figure 4. Additional characterization of diabetic and control Lrg1+/+ and Lrg1−/− mice at 20 weeks post-DM.

Supplemental Figure 5. Flow diagram of patient selection into study cohort.

Supplemental Table 1. BP measurements of diabetic and control mice.

Supplemental Table 2. Baseline characteristics of patients with DKD.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System : Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage-Renal-Disease in the United States, 2011. Available at : https://www.usrds.org/atlas11.aspx. Accessed February 24, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD; The Collaborative Study Group : The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 329: 1456–1462, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al.: Collaborative Study Group : Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 345: 851–860, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al.: RENAAL Study Investigators : Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Zeeuw D, Heerspink HJL: Unmet need in diabetic nephropathy: Failed drugs or trials? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 4: 638–640, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, Duckworth W, et al.: VA NEPHRON-D Investigators : Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 369: 1892–1903, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, de Zeeuw D, Haffner SM, Solomon SD, et al.: ALTITUDE Investigators : Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 367: 2204–2213, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Zeeuw D, Akizawa T, Audhya P, Bakris GL, Chin M, Christ-Schmidt H, et al.: BEACON Trial Investigators : Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2492–2503, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterby R, Nyberg G: New vessel formation in the renal corpuscles in advanced diabetic glomerulopathy. J Diabet Complications 1: 122–127, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyengaard JR, Rasch R: The impact of experimental diabetes mellitus in rats on glomerular capillary number and sizes. Diabetologia 36: 189–194, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo M, Ricardo SD, Deane JA, Shi M, Cullen-McEwen L, Bertram JF: A stereological study of the renal glomerular vasculature in the db/db mouse model of diabetic nephropathy. J Anat 207: 813–821, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karalliedde J, Gnudi L: Endothelial factors and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care 34[Suppl 2]: S291–S296, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dei Cas A, Gnudi L: VEGF and angiopoietins in diabetic glomerulopathy: How far for a new treatment? Metabolism 61: 1666–1673, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung SH, Ziyadeh FN, Wang A, Pyagay PE, Kanwar YS, Chen S: Blockade of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling ameliorates diabetic albuminuria in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3093–3104, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis B, Dei Cas A, Long DA, White KE, Hayward A, Ku CH, et al.: Podocyte-specific expression of angiopoietin-2 causes proteinuria and apoptosis of glomerular endothelia. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2320–2329, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeansson M, Gawlik A, Anderson G, Li C, Kerjaschki D, Henkelman M, et al.: Angiopoietin-1 is essential in mouse vasculature during development and in response to injury. J Clin Invest 121: 2278–2289, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dessapt-Baradez C, Woolf AS, White KE, Pan J, Huang JL, Hayward AA, et al.: Targeted glomerular angiopoietin-1 therapy for early diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 33–42, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuen DA, Stead BE, Zhang Y, White KE, Kabir MG, Thai K, et al.: eNOS deficiency predisposes podocytes to injury in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1810–1823, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao HJ, Wang S, Cheng H, Zhang MZ, Takahashi T, Fogo AB, et al.: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency produces accelerated nephropathy in diabetic mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2664–2669, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa T, Sato W, Glushakova O, Heinig M, Clarke T, Campbell-Thompson M, et al.: Diabetic endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice develop advanced diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 539–550, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satchell SC, Tooke JE: What is the mechanism of microalbuminuria in diabetes: A role for the glomerular endothelium? Diabetologia 51: 714–725, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haraldsson B, Nyström J: The glomerular endothelium: New insights on function and structure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 21: 258–263, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weil EJ, Lemley KV, Mason CC, Yee B, Jones LI, Blouch K, et al.: Podocyte detachment and reduced glomerular capillary endothelial fenestration promote kidney disease in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 82: 1010–1017, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu J, Wei C, Zhang W, Schlondorff D, Wu J, Cai M, et al.: Gene expression profiles of glomerular endothelial cells support their role in the glomerulopathy of diabetic mice. Kidney Int 94: 326–345, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi N, Takahashi Y, Putnam FW: Periodicity of leucine and tandem repetition of a 24-amino acid segment in the primary structure of leucine-rich alpha 2-glycoprotein of human serum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82: 1906–1910, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Zhang Y, Qiu F, Qiu Z: Proteomic identification of exosomal LRG1: A potential urinary biomarker for detecting NSCLC. Electrophoresis 32: 1976–1983, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen JD, Boylan KL, Jemmerson R, Geller MA, Misemer B, Harrington KM, et al.: Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein-1 is upregulated in sera and tumors of ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res 3: 21, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindén M, Lind SB, Mayrhofer C, Segersten U, Wester K, Lyutvinskiy Y, et al.: Proteomic analysis of urinary biomarker candidates for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Proteomics 12: 135–144, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furukawa K, Kawamoto K, Eguchi H, Tanemura M, Tanida T, Tomimaru Y, et al.: Clinicopathological significance of leucine-rich α2-Glycoprotein-1 in sera of patients with pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 44: 93–98, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Abraham S, McKenzie JAG, Jeffs N, Swire M, Tripathi VB, et al.: LRG1 promotes angiogenesis by modulating endothelial TGF-β signalling. Nature 499: 306–311, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Böttinger EP, Bitzer M: TGF-beta signaling in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2600–2610, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goumans MJ, Mummery C: Functional analysis of the TGFbeta receptor/Smad pathway through gene ablation in mice. Int J Dev Biol 44: 253–265, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pardali E, ten Dijke P: Transforming growth factor-beta signaling and tumor angiogenesis. Front Biosci 14: 4848–4861, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seki T, Yun J, Oh SP: Arterial endothelium-specific activin receptor-like kinase 1 expression suggests its role in arterialization and vascular remodeling. Circ Res 93: 682–689, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh SP, Seki T, Goss KA, Imamura T, Yi Y, Donahoe PK, et al.: Activin receptor-like kinase 1 modulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in the regulation of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 2626–2631, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren B, Deng Y, Mukhopadhyay A, Lanahan AA, Zhuang ZW, Moodie KL, et al.: ERK1/2-Akt1 crosstalk regulates arteriogenesis in mice and zebrafish. J Clin Invest 120: 1217–1228, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan Y, Li X, Xiao W, Fu J, Harris RC, Lindenmeyer M, et al.: BAMBI elimination enhances alternative TGF-β signaling and glomerular dysfunction in diabetic mice. Diabetes 64: 2220–2233, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fraser ST, Hadjantonakis AK, Sahr KE, Willey S, Kelly OG, Jones EA, et al.: Using a histone yellow fluorescent protein fusion for tagging and tracking endothelial cells in ES cells and mice. Genesis 42: 162–171, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong F, Mallipattu SK, Estrada C, Menon M, Salem F, Jain MK, et al.: Reduced krüppel-like factor 2 aggravates glomerular endothelial cell injury and kidney disease in mice with unilateral nephrectomy. Am J Pathol 186: 2021–2031, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tayo BO, Teil M, Tong L, Qin H, Khitrov G, Zhang W, et al.: Genetic background of patients from a university medical center in Manhattan: Implications for personalized medicine. PLoS One 6: e19166, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nadkarni GN, Galarneau G, Ellis SB, Nadukuru R, Zhang J, Scott SA, et al.: Apolipoprotein L1 Variants and blood pressure traits in African Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol 69: 1564–1574, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al.: CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu J, Wei C, Lee K, Zhang W, He W, Chuang P, et al.: Comparison of glomerular and podocyte mRNA profiles in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1006–1014, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodgin JB, Nair V, Zhang H, Randolph A, Harris RC, Nelson RG, et al.: Identification of cross-species shared transcriptional networks of diabetic nephropathy in human and mouse glomeruli. Diabetes 62: 299–308, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang F, Flanagan J, Su N, Wang LC, Bui S, Nielson A, et al.: RNAscope: A novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J Mol Diagn 14: 22–29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng S, Noonan WT, Metreveli NS, Coventry S, Kralik PM, Carlson EC, et al.: Development of late-stage diabetic nephropathy in OVE26 diabetic mice. Diabetes 53: 3248–3257, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steffes MW, Brown DM, Mauer SM: Diabetic glomerulopathy following unilateral nephrectomy in the rat. Diabetes 27: 35–41, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andeen NK, Nguyen TQ, Steegh F, Hudkins KL, Najafian B, Alpers CE: The phenotypes of podocytes and parietal epithelial cells may overlap in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 88: 1099–1107, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puelles VG, van der Wolde JW, Schulze KE, Short KM, Wong MN, Bensley JG, et al.: Validation of a three-dimensional method for counting and sizing podocytes in whole glomeruli. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 3093–3104, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guedez L, Rivera AM, Salloum R, Miller ML, Diegmueller JJ, Bungay PM, et al.: Quantitative assessment of angiogenic responses by the directed in vivo angiogenesis assay. Am J Pathol 162: 1431–1439, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guillot N, Kollins D, Badimon JJ, Schlondorff D, Hutter R: Accelerated reendothelialization, increased neovascularization and erythrocyte extravasation after arterial injury in BAMBI-/- mice. PLoS One 8: e58550, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jha JC, Banal C, Chow BS, Cooper ME, Jandeleit-Dahm K: Diabetes and kidney disease: Role of oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 25: 657–684, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Xu J, Zhang X, Wang C, Huang Y, Dai K, et al.: TNF-α-induced LRG1 promotes angiogenesis and mesenchymal stem cell migration in the subchondral bone during osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis 8: e2715, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navarro-González JF, Mora-Fernández C: The role of inflammatory cytokines in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 433–442, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lynch J, Fay J, Meehan M, Bryan K, Watters KM, Murphy DM, et al.: MiRNA-335 suppresses neuroblastoma cell invasiveness by direct targeting of multiple genes from the non-canonical TGF-β signalling pathway. Carcinogenesis 33: 976–985, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yan Z, Xiong Y, Xu W, Gao J, Cheng Y, Wang Z, et al.: Identification of hsa-miR-335 as a prognostic signature in gastric cancer. PLoS One 7: e40037, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J, Feng Z, Chen L, Wang X, Deng H: MicroRNA-335-5p inhibits osteoblast apoptosis induced by high glucose. Mol Med Rep 13: 4108–4112, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varga J, Pasche B: Antitransforming growth factor-beta therapy in fibrosis: Recent progress and implications for systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 20: 720–728, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sureshbabu A, Muhsin SA, Choi ME: TGF-β signaling in the kidney: Profibrotic and protective effects. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F596–F606, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voelker J, Berg PH, Sheetz M, Duffin K, Shen T, Moser B, et al.: Anti-TGF-β1 antibody therapy in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 953–962, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lebrin F, Deckers M, Bertolino P, Ten Dijke P: TGF-beta receptor function in the endothelium. Cardiovasc Res 65: 599–608, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Serada S, Fujimoto M, Ogata A, Terabe F, Hirano T, Iijima H, et al.: iTRAQ-based proteomic identification of leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a novel inflammatory biomarker in autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 69: 770–774, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ha YJ, Kang EJ, Lee SW, Lee SK, Park YB, Song JS, et al.: Usefulness of serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a disease activity biomarker in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Korean Med Sci 29: 1199–1204, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kentsis A, Ahmed S, Kurek K, Brennan E, Bradwin G, Steen H, Bachur R: Detection and diagnostic value of urine leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein in children with suspected acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med 60: 78–83 e71, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shinzaki S, Matsuoka K, Iijima H, Mizuno S, Serada S, Fujimoto M, et al.: Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a serum biomarker of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis 11: 84–91, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu JJ, Pek SLT, Ang K, Tavintharan S, Lim SC; SMART2D study : Plasma leucine-rich α-2-Glycoprotein 1 predicts rapid eGFR decline and albuminuria progression in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102: 3683–3691, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.