Even as the US health care system progresses towards increasing adoption of alternative payment models such as Accountable Care Organizations, traditional fee-for-service (FFS) continues to be the most commonly used method of payment for physicians. Moreover, although ACOs and other alternative payment models (APMs) often include budgets that put organizations at risk for spending, FFS payments continue to be the principal method of payment under these models, and are used to track spending against the budgets. Thus, challenges with FFS payment will not be solved simply by more rapid adoption of APMs.

One of the major criticisms of the FFS system is that it penalizes those such as primary care physicians who principally rely on evaluation and management (E&M) services. This issue has been a perennial criticism of the Medicare fee schedule, even after the implementation of the resource based relative value scale (RBRVS) payment system, which was in part designed to address this problem.1 Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed a substantial revision to E&M payments. Under this proposal, CMS would replace the graded payments for the increasingly complex level 2–5 visits with a single flat payment rate.2 Though this proposed rule would ease documentation requirements for those providing E&M services, total payment levels for these services would be relatively unchanged. Although the CMS proposal would be a substantial revision to E&M payments, it still maintains features of the current system for updating RVU values of existing services and adding relative values for new services that have exacerbated distortions in payment over time. Below I argue that any change to make E&M payments better reflective of the work involved in delivering such services should address these features of the system as well.

The first of these features relates to the process used for valuing new services and updating existing services. Though it maintains final approval, the CMS largely delegates this activity to the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (the RUC), a 31 member committee appointed by the American Medical Association. To set or update these values, the RUC relies on specialty society surveys, typically of at least 30 physicians, that present a case vignette and ask respondents to rate the work involved in the procedure as compared to existing procedures. These surveys are un-validated self-reports, however, and the Government Accountability Office has found that respondents typically have a vested interest in over-reporting time and effort.3 Moreover, at the time a procedure is first introduced, it often is time consuming and difficult, and thus deserving of a relatively high RVU value. Over time, however, as physicians gain more experience with a new procedure and new technologies are introduced to make the procedure easier and safer to perform, downward adjustments to the RVU values (when they are made) often fail to accurately reflect the decreased time and effort required to perform the procedure.4 For instance, a 2013 study showed that hourly revenue for performing a colonoscopy was four times that of a similarly time intensive complex E&M visit, even after WRVUs for colonoscopy had been reduced several times.5

The updating feature of RBRVS is particularly important because Congress stipulated that these updates must be budget neutral, which is the second problematic feature.6 To the extent that highly paid new codes are introduced or split off from existing codes, the payments for all other codes are adjusted downward to compensate by lowering the conversion factor (the factor multiplied times the relative value units to determine the actual payment amount). The impact of this budget neutrality adjustment has important implications for payments for E&M services, which absorb the largest part of this downward adjustment because they are by far the most frequently used codes. Moreover, in contrast to procedures where efficiency gains as noted above are possible, the work content of E&M requires physician time and is not subject to the same efficiency gains. If anything, E&M work content has been increased, rather than decreased, by technological innovations such as the electronic health record, and many would argue that the issues that need to be addressed by primary care physicians and other cognitive specialists have only increased in complexity over time.

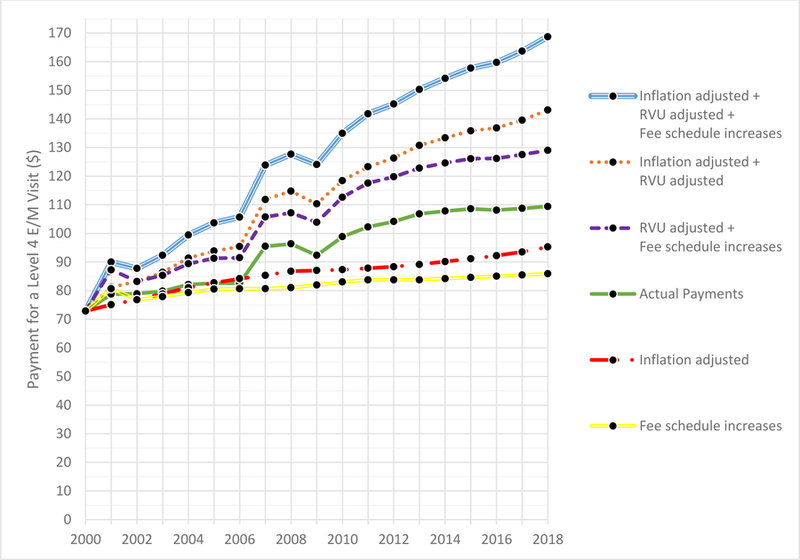

The impact of these features is illustrated in the Figure, which shows payments for an office-based physician providing a complex (level 4) E&M visit from 2000 and 2018 under various assumptions. The first important point is that the value of the conversion factor actually went down slightly from 2000 to 2018 ($36.6 to $36.0), despite the fact that the Congress authorized total payment increases to the physician fee schedule that cumulatively amounted to almost 18% over that time period (shown in the yellow line). As a result, increases to E&M payments over that time period were solely due to the periodic adjustments to the values of the RVUs as reflected in actual payments (green line). Although this might seem like a reasonable size increase, it amounts to a compound annual growth rate of just under 3.0% per year, starting from a time when E&M payments were already considered to be low. Over the same time period, cumulative general inflation was approximately 50%, and CMS’s more conservative Medicare Economic Index (seen in the red line), a measure of practice cost inflation, increased by over 30%. If fee increases had kept up with both medical inflation and the changes in the value of E&M RVUs, they would be over 30% higher than they are currently (orange line) and if they had kept up with inflation, legislated fee schedule increases, and changes in RVUs, they would be over 50% higher (blue line).

Figure 1. Evaluation and Management Payments for Level 4 Evaluation/Management Visits over Time under Various Scenarios.

Fee schedule increases includes overall increases in the fee schedule that were passed by Congress.

Inflation adjusted is based on the Medicare Economic Index, a measure of practice cost inflation developed by CMS.

Actual payments are the payments for a 99214 visit at a particular time.

RVU Adjusted refers to adjustments to the relative value units that determine E&M payments that were periodically made over the study period.

The conversion factor, annual RVU values, and actual payment data were obtained from Medicare Fee Schedule Search Tool (https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx).

The Medical Expenditure Index was obtained from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/MarketBasketData.html.

Clearly this suggests that fixing payment levels for primary care and others providing E&M services will require both strategies to adjust current levels of payments as well as strategies to mitigate the deleterious consequences of the updating process described above. CMS has taken several concrete steps related to the first strategy such as expanding the number and types of billable services for primary care, such as introducing payments for annual wellness visits, transitional care management, and chronic care management services. But the uptake of these auxiliary codes has been low, likely related to the complex requirements that need to be met to bill for these codes, and whether these improve care is debated.7 Moreover, billing for these codes introduces additional complexity related to documentation and service delivery that goes against the spirit of the proposed payment rule.

A complementary approach that would more directly address issues related to the current updating system would be to remove payments for E&M services performed by primary care physicians and other cognitive specialists from the set of services that must be adjusted downward to accommodate increased spending on new or revised procedure codes. This proposal could be implemented simply by establishing a separate conversion factor for these services. Such a policy would serve two functions. First, it would keep actual payments for primary care and other cognitive-based specialties flat or allow them to increase at the rate of increase in the overall fee schedule that is written into legislation. Second, it would directly address (at least in part) the downward stickiness of procedural RVUs by causing existing procedure payments to absorb the increases for new or updated procedures that are introduced over time. This approach also would directly address the concerns of PCPs and other cognitive specialists that the RUC is more reflective of the interests of procedural specialists.

Although the RBRVS was designed to improve the fairness of the reimbursement system, the combination of the updating process and budget neutrality requirements have resulted in substantially lower payments for E&M services over time. As adjustments to payments for primary care are debated, addressing these other features of the system should also be considered. One other simple policy alternative would be to create a separate conversion factor for some set of E&M services. This would accomplish two aims. First, it would help to prevent further erosion of E&M payment rates. Second, it would create additional downward pressure on existing procedure payments with the introduction of new costly procedures that better reflect increases in efficiency seen for procedures over time.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Russel Phillips, MD, MPH and Robert Berenson, MD for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript, and Aakash Jain for research assistance.

References

- 1.Hsiao WC, Braun P, Dunn D, Becker ER. Resource-based relative values. An overview. Jama 1988;260:2347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services DoHaHS. Medicare Program: Revisions to Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2019; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; etc. Federal Register 2018;83:665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government Accoutability Office. Medicare Physician Payment Rates: Better Data and Greater Transparency Could Improve Accuracy. Report to Congressional Committees 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.MEDPac. Report to Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinsky CA, Dugdale DC. Medicare payment for cognitive vs procedural care: minding the gap. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1733–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services DoHaHS. Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2016. Federal Register 2015;80:70885 – 1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bindman AB, Cox DF. Changes in Health Care Costs and Mortality Associated With Transitional Care Management Services After a Discharge Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]