Abstract

Direct measurement of the n-octanol partition coefficients (KOW) for highly hydrophobic organic chemicals is extremely difficult because of the extremely low concentrations present in the water phase. n-Butanol/water partition coefficients (KBW) are generally much lower than KOW due to the increased solubility of solute in the alcohol saturated aqueous phase, and therefore become easier to measure. We measured the KBW for 25 neutral organic chemicals having measured log KOWs ranging from 2 to 9 and 4 additional highly hydrophobic chemicals, with unmeasured KOWs, having estimated log KOWs ranging from 6 to 18. The measured log KBW and log KOW values were linearly related, r2= 0.978, and using the regression developed from the data, KOWs were predicted for the 4 highly hydrophobic chemicals with unmeasured KOWs. The resulting predictions were orders of magnitude lower than those predicted by a variety of computational models and suggests the estimates of KOW in the literature for highly hydrophobic chemicals (i.e., log KOW greater than 10) are likely incorrect by several orders of magnitude.

Keywords: n-octanol/water partition coefficients (KOW), Collander equation, n-butanol/water partition coefficients

Introduction

Regulatory authorities and other stakeholders across the globe are tasked with assessing the risks of new and existing chemicals to human health and the environment. In many circumstances, these assessments must be made without the benefit of measured values for important environmental fate and effect processes, such as soil/sediment partitioning, or bioaccumulation by fish. For neutral organic chemicals, the n-octanol/water partition coefficient (KOW) has been shown to be quantitatively related to many processes important to risk assessment. Early bioaccumulation models for fish were based entirely on KOW (e.g., log BCF = 0.85 log KOW −0.70; (Veith et al., 1979)), and KOW has remained a fundamental parameter for estimating bioaccumulation in more recent and more sophisticated models (Connolly, 1991; Thomann et al., 1992; Arnot and Gobas, 2004; Barber et al., 2017). KOW is also used within PBTK (Physiologically Based ToxicoKinetic) models to predict blood-water partitioning (Poulin and Krishnan, 1995) and partitioning among tissues (Bertelsen et al., 1998). KOW has also been shown to be the largest source of uncertainty in applying food-web models to predict residues in fish tissues for chemicals with KOW larger than 104 (Burkhard, 1998; Ciavatta et al., 2009).

Measurement of KOWs for highly hydrophobic organic chemicals, i.e., log KOW greater than 10, is difficult, in part, due to the exceeding low concentrations of the chemicals in the aqueous phase. For example, decachlorobiphenyl (PCB-209) with a log KOW of 8.22 (Tolls et al., 2003) can be measured successfully using a slow stir procedure (OECD, 2006) with an aqueous phase sample of 0.5 L, based on a water concentration mean of 32 ppb and a detection limit of approximately 0.2 ppb. Assuming the same analytical sensitivity, a chemical with a log KOW of 12.22 would require the equilibration, extraction, and analysis of an aqueous phase sample of 5,000 L-- clearly, a very difficult if not impossible experimental measurement to perform.

Measurement of KOWs for highly hydrophobic organic chemicals using the generator column technique (Devoe et al., 1981; Tewari et al., 1982; Woodburn et al., 1984; US-EPA, 1996) has similar difficulties. In general, these methods use HPLC pumps and column hardware, and are configured for flowrates of 5 mL/min and less. With a 5 mL/min flowrate, collection of a 5,000 L sample would take 694 d. Scaling columns up in size to 0.1 and 1.0 L/min flowrates would result in collection times of 34.7 and 3.47 d for a 5,000 L sample, respectively. In addition, as noted by Kuramochi et al (Kuramochi et al., 2007), micro-emulsions can be a problem with the generator column technique for chemicals with higher KOWs. These issues make the experimental measurements with generator column problematic for highly hydrophobic chemicals.

Another issue with both the slow stir and generator column techniques is the low solubility of highly hydrophobic chemicals in n-octanol saturated with water. With lower solubility in the alcohol phase, concentrations in the aqueous phase are further lowered. For example, assuming similar KOWs between two chemicals, one with ppm solubility and another with ppb solubility in n-octanol, the concentrations in the aqueous phase are three orders of magnitude lower for the latter chemical from solubility considerations alone.

Because of these measurement difficulties, most highly hydrophobic organic chemicals lack measured KOW values, forcing assessments of environmental behavior and bioaccumulation potential to be based on computationally derived estimates. Unfortunately, estimated KOWs for highly hydrophobic chemicals vary substantially across commonly used KOW estimation algorithms. For example, decabromodiphenyl ethane (BDEthane-209) has predicted KOW values spanning 6 orders of magnitude: log KOW of 7.72 (OPERA (https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/)), 7.87 (Tetko et al., 2005), 8.70 (Wania and Dugani, 2003), 9.16 (Yue and Li, 2013), 9.68 (NICEATM via https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/), 10.56 (Admire et al., 2015)), 11.1 (ACD via http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.82781.html (accessed 15:39, Apr 6, 2017)), 12.4 (Chemaxon via CSID:82781, http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.82781.html (accessed 15:39, Apr 6, 2017)), 12.3 (Carreira et al., 1994; Hilal et al., 1995), and 13.6 (US-EPA, 2012). From these estimates, BDEthane-209 is most likely highly hydrophobic with a log KOW of greater than 9. Nevertheless, the resulting uncertainty in selecting a KOW is folded into the uncertainties associated with environmental behavior and bioaccumulation models used in risk assessments of such chemicals.

The intractability of using slow-stir methodologies to directly measure KOW for highly hydrophobic chemicals and the issues associated with scaling the generator column methodology to high flowrates, e.g., 0.10 to 10 L/min, has led to the exploration of other approaches that use empirical chemical measurements to estimate KOW. One such approach is to use a correlation between HPLC retention times/capacity factors and measured KOWs (OECD, 2004). Currently, due to the lack of chemicals with measured log KOWs greater than 10, this method requires extrapolations well beyond the chemicals with known KOWs, i.e., the retention times/capacity factors are much longer/larger than those for chemicals with known KOWs, and leads to large uncertainties in the forecasted KOWs.

Recently, Jonker (Jonker, 2016) developed a method using polydimethylsiloxane-coated solid-phase microextraction fibers for measuring KOW. In the method, the KOW is determined from slow-stirring dual-flask/solid phase extraction system where concentrations of the chemical in the fiber and octanol phases after equilibration are measured. With chemical concentration in the fiber and fiber-water partition coefficient, the concentration in the aqueous phase is estimated and subsequently, used to calculate the KOW of the chemical. The method requires the fiber-water partition coefficient and for highly hydrophobic chemicals, their determination will be challenging. Additionally, the method required equilibration times of 18–20 weeks. Overall, the fiber method extends the range where experimental measurements are possible but does have limitations (Jonker, 2016).

Another approach is to use extrathermodynamic relationships (linear free-energy relationships) (Wold, 1974; Leffler and Grunwald, 2013) between partition coefficients in different solvents. Collander (Collander, 1951) demonstrated that relationships of the form:

| (1) |

exists for numerous solvent pairs where Ksolvent-1/water and Ksolvent-2/water are solvent-1/water and solvent-2/water equilibrium partition coefficients for organic chemicals. Leo et al. (Leo et al., 1971; Leo and Hansch, 1971) provided further follow-up comparisons and developed 20 solvent pair relationships with n-octanol/water partition coefficients (KOW) being the independent variable in all cases (solvent-2/water in equation 1). Like the HPLC method, the lack of chemicals with measured log KOWs greater than 10 limits this approach for estimating the KOWs of highly hydrophobic chemicals. Therefore, further development of the Collander relationship will simply provide an extended approach for estimating highly hydrophobic chemical’s log KOWs via measured log KBWs.

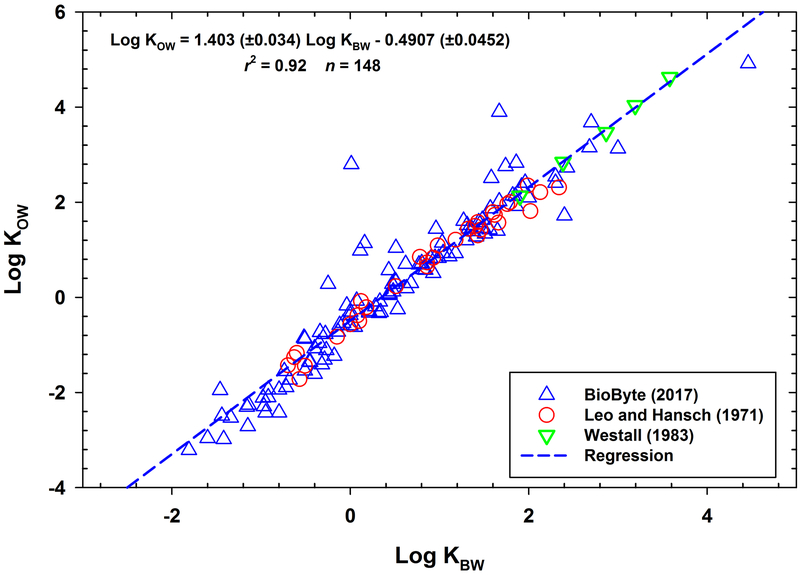

In the relationships developed by Leo et al. (Leo et al., 1971; Leo and Hansch, 1971), the slopes of the n-butanol/water (KBW) and n-pentanol/water (solvent-2/water) against KOW (solvent-1/water) were 1.43 and 1.24, respectively. With slopes greater than 1.0, the n-butanol/water and n-pentanol/water partition coefficients are less than KOWs. As discussed by Chiou (Chiou, 2003), n-butanol is much more polar than n-octanol and therefore has a greater solubility in water which causes nonpolar solutes to have a lower affinity for water-saturated n-butanol compared to water-saturated n-octanol resulting in KBW < KOW. In Figure 1, log KOW data from BioByte (BioByte, 2017), Leo and Hansch (Leo and Hansch, 1971), and Westall (Westall, 1983) are plotted against their log KBWs, and range of log KOWs extends from −3.21 to 4.92. The data in Figure 1 spans a wide variety of chemical classes and includes sugars, alcohols, phenols, aromatic and aliphatic acids, amines, drugs, and chlorinated benzenes.

Fig. 1.

Log KOW vs. Log KBW for existing literature data. Regression coefficients (± standard error).

The KBW-KOW correlation shown in Figure 1 demonstrates a strong linear relationship over a series of chemicals with log KOWs < 5. However, the range of the available data does not provide much support for confidently applying this regression to chemicals with log KOWs > 5. Based on this, the objective of this study was 4-fold. The first objective was to measure additional KBWs for chemicals with measured log KOWs ranging from 2 to 9 and for chemicals with estimated log KOWs exceeding 10. The second objective was to expand the KBW-KOW correlation shown in Figure 1 using the newly measured KBWs and subsequently evaluate the relationship. The third objective was to measure KOWs for a few highly hydrophobic chemicals to further evaluate the KBW-KOW relationship. The fourth objective was to make predictions for highly hydrophobic chemicals, i.e., estimated log KOW > 10, with KBW-KOW relationship and compare these predictions to estimates from log KOW calculators.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Glassware Cleaning

See Supplementary Data: Tables S1-S4 for details on all chemicals and solvents used. Prior to use, n-octanol and n-butanol were further purified by distillation, with distillate collection between the alcohol boiling point and 5 °C beyond.

To eliminate cross contamination and minimize background, after washing with soap and water, all glassware was combusted at 450 °C for 4 h prior to use. The Teflon stir-bars used were cleaned with a Dionex 300 Accelerated Solvent Extractor using dichloromethane:acetone (1:1, v/v).

Slow Stir Measurement Methodology

n-Butanol and n-octanol/water partition coefficients were measured following the OECD slow stir technique (OECD, 2006). Glass jacketed reservoirs (2 L and 5 L Radnoti reservoirs, Covina, CA, USA) were set up on magnetic stir plates with water jacket spouts connected to a recirculating bath with a controlled temperature of 25.00±0.05 °C. Deionized (DI) water (saturated with n-butanol or n-octanol) was added to the reservoirs and allowed to reach temperature. Chemical dissolved in n-butanol or n-octanol (saturated with DI water) was then slowly added to the reservoirs carefully avoiding emulsion formation. After chemical was added to the reservoirs, slow-stirring was started with a vortex at the water/n-alcohol interface of less than 2.0 cm in depth and the reservoirs were covered with aluminum foil to avoid any possible photodegradation. Start times for sample collections were based solely on an estimated chemical equilibration time. Prior to sampling the reservoirs, stirring was stopped and the reservoirs were allowed to rest until quiescent conditions were obtained.

Sampling of the n-alcohol phase was done using a Pasteur pipette through the neck of the reservoir. After sampling, a subsample of n-alcohol phase was diluted using toluene or ACN, and the dilution was spiked with surrogate chemical.

For the aqueous phase, sampling was performed by draining 10–20 mL of the aqueous phase through sampling line and value to waste, and then, collecting 0.1–2 L of sample into a flask. The collected aqueous sample was analyzed using one of two methods. The first method involved the direct dilution of a subsample of the aqueous solution with ACN for analysis with HPLC instrumentation. This method was used for the polyaromatic hydrocarbons, see Supplementary Data: Table S5 for specific chemicals analyzed using this method.

The second method involved the collection of the aqueous sample into a tared volumetric flask containing the surrogate standard after evaporation of its solvent. The pre- and post-sample collection mass of the volumetric flask was used to determine the sample volume. Aqueous phase samples were liquid-liquid extracted 3x with hexane in the volumetric flasks. Prior to extraction, DI water saturated with Na2SO4 was added (1% sample volume) to the flask to prevent emulsion formation during extraction. Extraction flasks were mixed vigorously using a Teflon stir-bar for at least 30 minutes and then allowed to settle. The hexane layer was pipetted off into a 60 mL test tube and evaporated using a N-Evap 111 nitrogen evaporator (Organomation, Berlin, MA) with a heated water bath maintained at a temperature range of 50–90 °C or a Rocket solvent evaporator (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Once hexane reached a volume < 1 mL, it was transferred to a micro-GC-vial via Pasteur pipette. The 60 mL test tube was rinsed 3x with hexane and pooled into the micro-vial. Samples were concentrated under N2 to a final volume of 20–200 µL, spiked with appropriate internal standard, and vortex mixed.

Quantification

Depending upon the chemical, analytes were quantified using one of the following systems: Agilent 6890N/5975C Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS), Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive Orbitrap coupled with a Trace 1310 Gas Chromatograph (QE-GC/MS), Thermo Scientific DFS High Resolution GC/MS, or an Agilent 1100 series High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled to fluorescence (FLD) or Diode Array (DAD) detector. Selected-ion monitoring (SIM) for target and confirming masses was used for mass spectrometer detection. Quantification was performed using the isotopic dilution method for chemicals that required liquid extraction. For the samples resulting from the direct dilution of the aqueous phase, they were analyzed using HPLC. See Supplemental Data: Table S5 for additional analytical details.

The n-butanol/water partition coefficients (log KBW) and n-octanol/water partition coefficients (log KOW) were computed using the equation:

| (2) |

In equation 2, log KAW is the alcohol/water partition coefficient that represents either n-butanol or n-octanol, CA is the concentration in the alcohol phase, and CW is the concentration in the water phase. n-Butanol and n-octanol/water partition coefficients are plotted against collection days, and for a successful log KAW measurement experiment, the slope of the regression of log KAW against time must be not significantly different from zero (α= 0.05) with a minimum of 4 collections over time (criteria in OECD 123 methodology (OECD, 2006)). Additional samples were collected where necessary to satisfy the equilibrium criterion.

An aqueous phase saturated with n-butanol or n-octanol was used as the method blank. Blanks were processed with each slow stir collection to monitor possible hexane extraction and sample preparation contamination. Aqueous phase sample concentrations were method blank corrected using the blank for the corresponding collection days.

Generator Column Measurement Methodology

An additional approach for measuring n-octanol/water partition coefficients was using the generator column technique (Woodburn et al., 1984; US-EPA, 1996). Stainless steel HPLC columns (25 cm in length with 2.0 µm frits) were packed with diatomaceous earth (Celite 545, Celite 560 or sieved >100 mesh Celite 560) with ½ cm of 100–120 mesh glass beads on the downstream end of the column. After measuring the concentration of the chemical in the water saturated n-octanol solution, the columns were coated with the solution using a gentle vacuum to draw the solution through the column. For each measurement, columns were placed in series in a water jacket connected to a recirculating bath with a temperature of 25.0±0.05 °C. Using Gilson HLPC 303 and 306 pumps, water saturated with n-octanol was passed through the columns and the exiting water passed through activated octadecyl solid phase extraction (SPE) columns (Bakerbond 7020–06). After sample collection, SPE columns were dried with nitrogen gas, spiked with the analytical surrogate solution, and then, eluted using hexane followed by toluene. The eluted extracts were concentrated using Rocket Evaporator to approximately 1 mL and then, to 200 µL using N-Evap nitrogen evaporator. The extracts were transferred to micro-GC-vials via Pasteur pipette with 3x rinses of hexane. Extracts were concentrated to a final volume of 20–200 µL, spiked with appropriate internal standard, and vortex mixed. Analytes were quantified using selected-ion monitoring with GC/MS systems described above.

Partition coefficients were computed using equation 2. For an individual chemical, partition coefficients were measured using different columns and different flowrates through the columns to demonstrate equilibrium conditions with the measurements (See Supplemental Data: Table S8 for experimental conditions).

Results and Discussion

In addressing the first objective of this study, we measured the KOW for three chemicals (benz[a]anthracene, benzo[a]pyrene, and PCB-209) for the purpose of insuring comparability between our measurement methods and the literature since we intended to combine our measure KBW values with KOW values. The measurements of PCB-209 by the two methods were essentially identical (average of 8.17 by slow stir and 8.18 by generator column; Table S6) and both values agree well with the literature value of 8.22 (Table 1). For further method validation, our measured slow stir value for benz[a]anthracene was 5.77 versus a literature average of 5.85. For benzo[a]pyrene, our measurement; is higher than the literature average (6.77 vs. 6.09; Table 1), though, our slow stir value is in good agreement with the recently reported slow stir value of 6.69±0.02 by Jonker (Jonker, 2016). Taken together we believe these results affirm the comparability of measurement methods, and support the use of literature KOW values in building a KBW-KOW relationship.

Table 1.

n-Butanol/water (KBW) and n-octanol/water partition coefficients (KOW).

| Chemical | Measured Log KBW | Measured Log KOW | Estimated Log KOWs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This Study a | Literature | This Study a | Literature b, d | Eq. Regression c | EPISuite | SPARC | ACD | |

| Benzene | 1.92 (0.02; 2) | 1.85 [1], 1.90 [2] | 2.13 | 1.90 | 1.99 | 2.06 | 2.22 | |

| Chlorobenzene | 2.43 (0.02; 2) | 2.38 [2] | 2.84 | 2.81 | 2.64 | 2.53 | 2.81 | |

| Bromobenzene | 2.53 (0.02; 2) | 2.99 | 2.98 | 2.88 | 2.67 | 2.99 | ||

| Naphthalene | 2.76 (0.02; 3) | 3.40 (0.17; 33) | 3.39 | 3.17 | 3.41 | 3.45 | ||

| Acenaphthene | 3.21 (0.04; 2) | 3.97 (0.21; 6) | 4.18 | 4.15 | 4.06 | 4.19 | ||

| Fluorene | 3.28 (0.02; 2) | 4.14 (0.12; 11) | 4.31 | 4.02 | 4.20 | 4.16 | ||

| Phenanthrene | 3.46 (0.01; 3) | 4.49 (0.14; 22) | 4.63 | 4.35 | 4.74 | 4.68 | ||

| Anthracene | 3.56 (0.06; 3) | 4.63 (0.25; 21) | 4.82 | 4.35 | 4.69 | 4.68 | ||

| PCB-1 | 3.64 (0.06; 3) | 4.54 (0.15; 4) | 4.95 | 4.40 | 4.65 | 4.45 | ||

| Fluoranthene | 3.73 (0.13; 3) | 5.00 (0.28; 17) | 5.11 | 4.93 | 5.29 | 5.17 | ||

| Pyrene | 3.74 (0.05; 3) | 5.10 (0.21; 14) | 5.12 | 4.93 | 5.25 | 5.17 | ||

| Chrysene | 4.07 (0.02; 4) | 5.69 (0.27; 13) | 5.72 | 5.52 | 5.90 | 5.91 | ||

| Benz[a]anthracene | 4.11 (0.02; 4) | 5.76 (0.14; 2) | 5.85 (0.08; 7) e | 5.79 | 5.52 | 5.85 | 5.91 | |

| Hexachlorobenzene | 4.19 (----; 1) | 5.53 (0.25; 17) | 5.93 | 5.86 | 6.04 | 4.89 | ||

| Benzo(g,h,i)perylene | 4.21 (0.20; 3) | 6.62 (0.51; 7) | 5.97 | 6.70 | 7.04 | 6.89 | ||

| Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene | 4.23 (0.16; 3) | 6.65 (0.43; 4) | 6.00 | 6.70 | 7.09 | 6.89 | ||

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 4.28 (0.03; 4) | 6.77 (0.21; 2) | 6.09 (0.31; 7) e | 6.08 | 6.11 | 6.54 | 6.40 | |

| PCB-77 | 4.68 (0.04; 3) | 6.58 (0.34; 3) | 6.80 | 6.34 | 6.28 | 6.00 | ||

| PCB-155 | 4.72 (0.10; 3) | 7.23 (0.28; 4) | 6.87 | 7.62 | 7.66 | 6.83 | ||

| Di-n-hexyl phthalate | 4.91 (0.04; 2) | 6.82 (0.10; 6) | 7.20 | 6.57 | 6.29 | 6.95 | ||

| PCB-209 | 5.20 (0.04; 5) | 8.18 (0.12, 4) | 8.22 (0.17; 10) e | 7.72 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 8.10 | |

| BDE-209 | 5.47 (0.04; 4) | 8.37 (0.21, 2) | 8.21 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 11.2 | ||

| Di-n-octyl phthalate | 5.52 (0.04; 2) | 8.15 (0.04; 3) | 8.28 | 8.54 | 8.03 | 9.08 | ||

| Di-n-decyl phthalate | 5.95 (0.05; 2) | 9.05 (0.31, 2) | 9.06 | 10.5 | 9.71 | 11.2 | ||

| TBPH | 6.21 (0.19; 2) | 9.21 (0.19; 2) | 9.52 | 12.0 | 10.9 | 10.8 | ||

average (propagated error, n).

average (standard deviation, n).

Predicted using Equation 3 and measured KBWs.

See Supplementary Data: Table S7 for sources of the literature log KOW values.

Measured log KOW from this study not included in literature average. 1 - (Westall, 1983). 2 - (Hansch et al., 1995).

We also measured log KOW for decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209; 8.37 by generator column) and bis-(2-ethylhexyl)-3,4,5,6-tetrabromophthalate (TBPH; 9.21 by slow stir), to provide additional data to help extend the KBW-KOW relationship at high log KOW. From a methodological perspective, measuring the KOWs of these highly hydrophobic chemicals was very demanding. The challenges for slow stir method included the extraction of large volumes of aqueous phase, long equilibration times, low solubilities of the chemicals in the alcohol phase, insuring that the chemical was dissolved in alcohol phase, and having analytical instrumentation optimized for the lowest detection limits possible. The OECD guidance (OECD, 2006) discusses these issues, and we cannot over-emphasize their importance to making these measurements. The challenges for the generator column method included pumping large volumes of water through the columns, getting the columns to come to equilibrium, dissolving the chemicals to coat the diatomaceous earth, and demonstrating that KOW was independent of flowrate conditions.

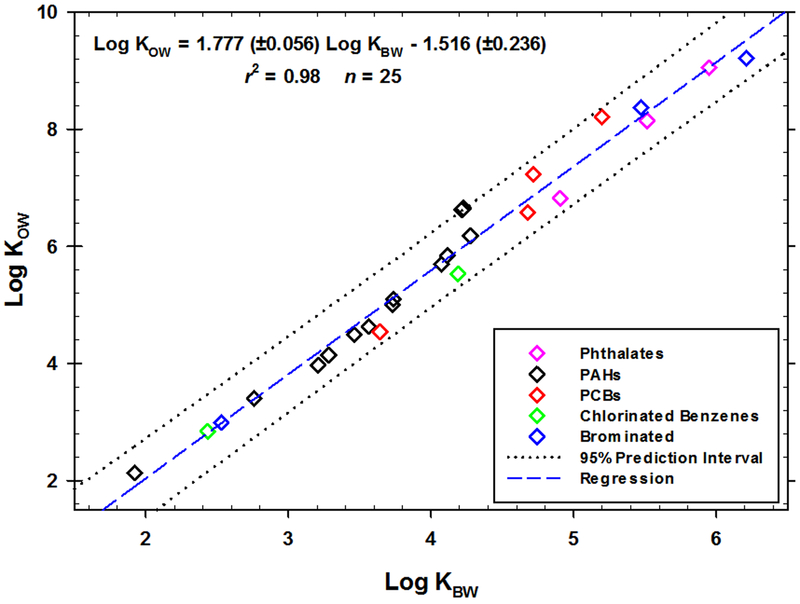

The log KBWs for 29 chemicals were measured using the OECD slow stir technique (Table 1 and Table 2). Among these chemicals, literature KBW values were available for benzene and chlorobenzene (Westall, 1983; Hansch et al., 1995; Table 1) and these agreed closely with our measurements (Table 1). The collected log KBWs from this study only and their available log KOWs data are shown in Figure 2. The data are plotted with the following regression equation:

| (3) |

Chemical classes were categorized to qualitatively show that there is no significant bias relating to compound structure (Figure 2). Additional data within each class would be needed to resolve any bias concerns.

Table 2.

Measured n-butanol/water (KBW) and estimated n-octanol/water partition coefficients (KOW).

| Chemical | Measured Log KBW | Estimated Log KOWs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This Studya | Eq. 3 Regressionb | OPERAc | Tetko et al.e | NICEATMc | Upperf | ACDg | Chemaxonh | SPARCi | EPISuitec | |

| BDEthane-209 | 5.60 (0.14, 2) | 8.43 (7.78 – 9.09) | 7.72d | 7.87 | 9.68 | 10.6 | 11.1 | 12.4 | 12.3 | 13.6 |

| m-TCP | 5.78 (0.06; 4) | 8.76 (8.09 – 9.45) | 8.47d | 9.79 | 9.73 | 13.2 | 11.7 | 12.7 | 15.1 | 14.5 |

| p-TCP | 5.82 (0.08; 4) | 8.82 (8.16 – 9.49) | 8.48d | 9.80 | 10.3 | 13.2 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 15.0 | 14.5 |

| p-QTCP | 6.47 (0.13; 3) | 9.98 (9.29 – 10.67) | 6.06d | 10.4 | 11.9 | 16.7 | 14.3 | 16.4 | 19.6 | 18.9 |

average (propagated error, n).

This study, predicted using Equation 3 and (95% prediction interval).

US-EPA via https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard (accessed August 15, 2018).

Prediction unreliable: Outside of global applicability domain and low local applicability domain.

ALOGPS 2.1 (Tetko et al., 2005).

Upper (Admire et al., 2015).

ACD via http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.82781.html (accessed August 15, 2018).

Chemaxon via http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.82781.html (accessed August 15, 2018).

Fig. 2.

Log KOWs vs. log KBWs measured in this study. Regression coefficients (± standard error).

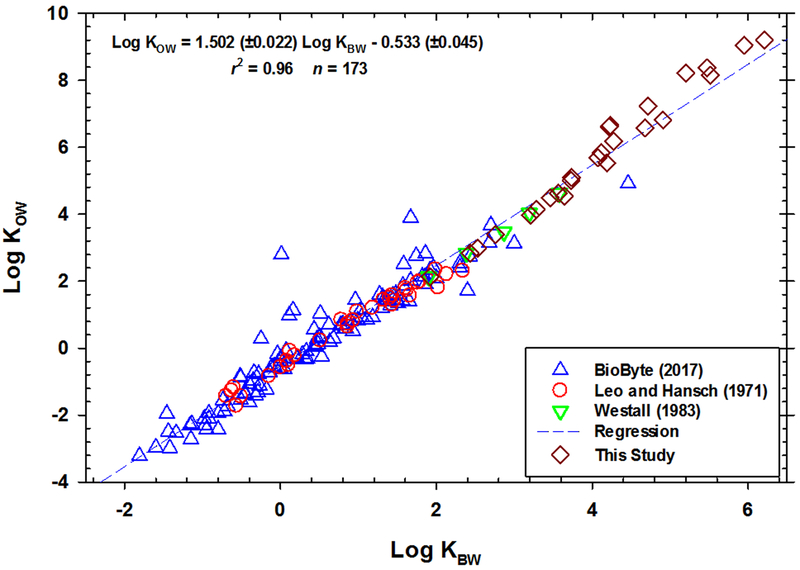

In Figure 3, our KBW (Table 1; Supplementary Data: Table S7) are plotted with literature values (shown in Figure 1) and supports/continues the linear trend previously depicted in Figure 1. The regression equation is:

| (4) |

Fig. 3.

All Log KOWs vs. log KBWs values. Regression coefficients (± standard error).

The residuals for the regressions are plotted in Supplementary Data: Figure S1-A-B. For the all data regression, there is a slight negative bias in residuals for chemicals with log KBWs ranging from 2 to 4 and a slight positive bias in residuals for chemicals with log KBWs above 4 (Supplementary Data: Figure S1-A). There is no thermodynamic basis, we believe, for the relationship to be nonlinear between KOW and KBW. The fit of the regression for the data collected within this study (Figure 2) is better in terms of the residuals, i.e., more evenly distributed across the range of KBWs in the measurements (Supplementary Data: Figure S1-B), and regression is based solely upon neutral hydrophobic organic chemicals. Therefore, the developed regression from this study i.e., Equation 3, will be used for estimating the KOWs for the 4 selected chemicals within this study, and will be beneficial for estimating additional KOWs for highly hydrophobic chemicals via their measured log KBWs.

In Table 1, the quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) estimated log KOWs are relatively consistent to our Eq. 3 regression KOW estimations for less hydrophobic chemicals. However, as chemicals become more hydrophobic, difference between Eq. 3 and other QSAR predictions increase greatly. This is noticeable around PCB-155 and beyond for QSAR log KOW estimations. Our Eq. 3 regression predictions are relatively comparable to the measured literature log KOWs for more hydrophobic chemicals, thus producing a reliable regression for estimating log KOWs where measuring KBW is feasible.

To address the fourth objective, we used the KBW-KOW regression formed within this study (Figure 2) to predict log KOWs for highly hydrophobic chemicals in which there are no literature data available. The log KBWs for tetradecachloro-m-terphenyl (m-TCP), tetradecachloro-p-terphenyl (p-TCP), and octadecachloro-p-quaterphenyl (p-QTCP) were successfully measured (Table 2). To meet the OECD equilibrium criteria of slopes not significantly different from zero with a minimum of four sampling points over time in the slow stir measurements, equilibration times ranging from 2 to 4 weeks were required for these chemicals. Shown in Table 2, log KOWs estimates using several different QSAR algorithms are provided ranging between 6–19.

The predicted log KOWs using equation 3 from our collected KBW data for the 4 highly hydrophobic chemicals are substainally lower than most of the KOWs forecasted by the selected QSAR models (Table 2). As an example, EPISuite, SPARC, and ACD prediction models are estimated up to 10 orders of magnitude higher compared to this study’s log KOW predictions for BDEthane-209, m-TCP, p-TCP, and p-QTCP. There is no clear reason for this, though, EPISuite, SPARC, and ACD algorithms use molecular fragmentation methods that are calibrated based on empirical datasets (Hilal and Karickhoff, 2004; Cabalo and Knox, 2014; Stenzel et al., 2014) and substantial extrapolation are needed due to the lack of measured data for highly hydrophobic chemicals. How the experimental data is assigned to a set of sub-structural fragments differ in the extent of correction factors, use of secondary regressions, and applied intermolecular interactions parameters. The majority of QSAR KOW estimations are primarily dependent on limited empirical parameters and the quality of empirical data available. Therefore, it becomes difficult to pinpoint what chemical parameters may cause log KOW over-predictions aside from the shortage of empirical data for highly hydrophobic chemicals. Other factors within QSAR models may include but are not limited to overbearing correction factors stimulated by compound symmetry (Cabalo and Knox, 2014), absence of quantum mechanic contributions such as molecular distortion/orbital hybridization, steric effects, etc., or molecular thermodynamic assumptions between similar chemical classes and sub-stuctures (Maggiora, 2006; Scior et al., 2009). OPERA log KOW predictions are relatively low for the 4 selected hydrophobic chemicals (Table 2), and the OPERA model estimates for log KOWs are based on a reviewed dataset of over 14,000 chemicals (Mansouri et al., 2018). Similarly, EPISuite predictions also implement a similar number of reviewed chemicals (e.g. 13,700) (US-EPA, 2012). Consequently, the estimations for highly hydrophobic chemicals lack experimental validation and therefore true accuracy is indefinite.

Conclusions

We have successfully expanded the KBW-KOW correlation shown in Figure 1 over a wider range of organic chemicals including several having log KOWs greater than 9. It was proven that KBWs are measurable for highly hydrophobic chemicals using the OECD slow stir technique for chemicals with estimated log KOWs greater than 10. With the developed linear correlation between KBW and KOW, measured KBWs can be used to estimate a chemical’s KOW and provide a more accurate estimate of KOW for chemicals. To illustrate the importance of having an unbiased estimate for a highly hydrophobic chemical, consider the KOW estimates ranging from 8.48 to 15.0 for p-TCP (Table 2). Using BCFBAF algorithm of EPISuite (US-EPA, 2012), log BAFs (bioaccumulation factor) for upper trophic level fish predicted for these KOW estimates range from 6.82 to 0.72 (L/kg (ww)), respectively. Assuming an environmentally low concentration of p-TCP in water of 1 pg/L (part per quadrillion), predicted residues in fish would range from 6,607,000 to 5.24 pg/kg (ww). This example demonstrates the importance of using accurate KOW measurements with predictive models for assessing a chemical’s environmental behavior and bioaccumulation.

To estimate log KOWs for highly hydrophobic chemicals, we recommend that one simply use the developed regression given in Eq. 3 with a KBW measured using the OECD slow stir methodology; i.e., the methodology used within this study. It is highly advised to measure KBWs for one or more less hydrophobic chemicals with known log KOWs for method validation. Additionally, predictions of log KOWs above 10 are extrapolations, and their accuracy are a bit tenuous without further experimental measurements. At this time, we have no basis for determining biases with Eq. 3, if any, related to differences in chemical classes. Additional KBW measurements and KOW measurements for additional highly hydrophobic chemicals are needed to address this question, to span Eq. 3 to higher KOWs, and to further validate the KOW–KBW relationship.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

n-Butanol/water partition coefficients are measurable for hydrophobic chemicals

Plot of log KOW vs log KBW is linear, r2=0.98, for KOWs extending into 109 range

KOWs were estimated using KOW-KBW relationship and measured KBWs

KOWs estimated for highly hydrophobic chemicals are lower than their QSAR estimates

Acknowledgements

We thank David Tobias for his comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. The information in this document has been funded wholly by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. It has been subjected to review by the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents reflect the views of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Footnotes

Appendix A: Supplementary Data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.141.

References

- Admire B, Lian B, Yalkowsky SH, 2015. Estimating the physicochemical properties of polyhalogenated aromatic and aliphatic compounds using UPPER: Part 2. Aqueous solubility, octanol solubility and octanol–water partition coefficient. Chemosphere 119, 1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnot JA, Gobas FA, 2004. A food web bioaccumulation model for organic chemicals in aquatic ecosystems. Environ Toxicol Chem 23, 2343–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber MC, Isaacs KK, Tebes-Stevens C, 2017. Developing and applying metamodels of high resolution process-based simulations for high throughput exposure assessment of organic chemicals in riverine ecosystems. Sci Total Environ 605, 471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen SL, Hoffman AD, Gallinat CA, Elonen CM, Nichols JW, 1998. Evaluation of log Kow and tissue lipid content as predictors of chemical partitioning to fish tissues. Environ Toxicol Chem 17, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar]

- BioByte, 2017. CLOGP. http://www.biobyte.com/index.html. BioByte Corporation, Claremont, CA USA. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard LP, 1998. Comparison of two models for predicting bioaccumulation of hydrophobic organic chemicals in a Great Lakes food web. Environ Toxicol Chem: An International Journal 17, 383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Cabalo JB, Knox CK, 2014. A Comparison of QSAR Based Thermo and Water Solvation Property Prediction Tools and Experimental Data for Selected Traditional Chemical Warfare Agents and Simulants. in: Center ECB (Ed.), 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira LA, Hilal S, Karickhoff SW, 1994. Estimation of Chemical Reactivity Parameters and Physical Properties of Organic Molecules Using SPARC in: Politzer P, Murray JS (Eds.). Theoretical and Computational Chemistry, Quantitative Treatment of Solute/Solvent Interactions, . Elsevier Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou CT, 2003. Partition and Adsorption of Organic Contaminants in Environmental Systems. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ciavatta S, Lovato T, Ratto M, Pastres R, 2009. Global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis of a food‐web bioaccumulation model. Environ Toxicol Chem 28, 718–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collander R, 1951. The partition of organic compounds between higher alcohols and water. Acta chem. scand 5, 774–780. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JP, 1991. Application of a food chain model to polychlorinated biphenyl contamination of the lobster and winter flounder food chains in New Bedford Harbor. Environ Sci Technol 25, 760–770. [Google Scholar]

- Devoe H, Miller MM, Wasik SP, 1981. Generator columns and high pressure liquid chromatography for determining aqueous solubilities and octanol-water partition coefficients of hydrophobic substances. J Res Natl Inst Stan 86, 361–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C, Leo A, Hoekman D, Livingstone D, 1995. Exploring QSAR: Hydrophobic, Electronic, and Steric Constants. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal S, Carreira L, Karickhoff S, 1995. Estimation of chemical reactivity parameters and physical properties of organic molecules using SPARC. J ChemInformatics 26. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal SH, Karickhoff SW, 2004. Prediction of the solubility, activity coefficient and liquid/liquid partition coefficient of organic compounds. QSAR Comb Sci 23, 709–720. [Google Scholar]

- Jonker MT, 2016. Determining octanol–water partition coefficients for extremely hydrophobic chemicals by combining “slow stirring” and solid‐phase microextraction. Environ Toxicol Chem 35, 1371–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi H, Maeda K, Kawamoto K, 2007. Physicochemical properties of selected polybrominated diphenyl ethers and extension of the UNIFAC model to brominated aromatic compounds. Chemosphere 67, 1858–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler JE, Grunwald E, 2013. Rates and Equilibria of Organic Reactions: As Treated by Statistical, Thermodynamic and Extrathermodynamic Methods. Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Leo A, Hansch C, Elkins D, 1971. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem Rev 71, 525–616. [Google Scholar]

- Leo AJ, Hansch C, 1971. Linear free energy relations between partitioning solvent systems. J Org Chem 36, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiora GM, 2006. On outliers and activity cliffs- why QSAR often disappoints. J. Chem. Inf. Model 46, 1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri K, Grulke CM, Judson RS, Williams AJ, 2018. OPERA models for predicting physicochemical properties and environmental fate endpoints. J ChemInformatics 10, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD, 2004. Test No. 117: Partition Coefficient (n-octanol/water), HPLC Method. OECD Publishing, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- OECD, 2006. Test No. 123: Partition Coefficient (1-Octanol/Water): Slow-Stirring Method. OECD Publishing, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin P, Krishnan K, 1995. An algorithm for predicting tissue: blood partition coefficients of organic chemicals from n‐octanol: water partition coefficient data. J Toxicol Env Health 46, 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scior T, Medina-Franco JL, Do Q-T, Martinez-Mayorga K, Yunes Rojas JA, Bernard P, 2009. How to recognize and workaround pitfalls in QSAR studies: a critical review. Curr Med Chem 16, 4297–4313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel A, Goss K-U, Endo S, 2014. Prediction of partition coefficients for complex environmental contaminants: validation of COSMOTHERM, ABSOLV, and SPARC. Environ Toxicol Chem 33, 1537–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetko IV, Gasteiger J, Todeschini R, Mauri A, Livingstone D, Ertl P, Palyulin VA, Radchenko EV, Zefirov NS, Makarenko AS, 2005. Virtual computational chemistry laboratory–design and description. ACS Sym Ser 19, 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari YB, Miller MM, Wasik SP, Martire DE, 1982. Aqueous solubility and octanol/water partition coefficient of organic compounds at 25.0 degree C. J Chem Eng Data 27, 451–454. [Google Scholar]

- Thomann RV, Connolly JP, Parkerton TF, 1992. An equilibrium model of organic chemical accumulation in aquatic food webs with sediment interaction. Environ Toxicol Chem 11, 615–629. [Google Scholar]

- Tolls J, Bodo K, De Felip E, Dujardin R, Kim YH, Moeller‐Jensen L, Mullee D, Nakajima A, Paschke A, Pawliczek JB, 2003. Slow‐stirring method for determining the n‐octanol/water partition coefficient (pow) for highly hydrophobic chemicals: Performance evaluation in a ring test. Environ Toxicol Chem 22, 1051–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US-EPA, 1996. Product Properties Test Guidelines: OPPTS 830.7560 Partition Coefficient (n-Octanol/Water), Generator Column Method EPA 712–C–96–039 August 1996. Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- US-EPA, 2012. Estimation Programs Interface Suite™ for Microsoft® Windows, v 4.11. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Veith GD, DeFoe DL, Bergstedt BV, 1979. Measuring and estimating the bioconcentration factor of chemicals in fish. J Fish Res Board Can 36, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Wania F, Dugani CB, 2003. Assessing the long‐range transport potential of polybrominated diphenyl ethers: a comparison of four multimedia models. Environ Toxicol Chem 22, 1252–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westall J, 1983. Properties of Organic Compounds in Relation to Chemical Binding. Proc Biofilm Processes in Ground Water Research, Stockholm, 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wold S, 1974. Theoretical foundation of extrathermodynamic relationships (linear free-energy relationships). Chem Scripta 5, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Woodburn KB, Doucette WJ, Andren AW, 1984. Generator column determination of octanol/water partition coefficients for selected polychlorinated biphenyl congeners. Environ Sci Technol 18, 457–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Li LY, 2013. Filling the gap: estimating physicochemical properties of the full array of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). Environ Pollut 180, 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.