Abstract

Undiagnosed liver disease remains an unmet medical need in pediatric hepatology, including children with high gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) cholestasis. Here, we report whole‐exome sequencing of germline DNA from 2 unrelated children, both offspring of consanguineous union, with neonatal cholestasis and high GGT of unclear etiology. Both children had a rare homozygous damaging mutation (p.Arg219* and p.Val204Met) in kinesin family member 12 (KIF12). Furthermore, an older sibling of the child homozygous for p.Val204Met missense mutation, who was also found to have cholestasis, had the same homozygous mutation, thus identifying the cause of the underlying liver disease. Conclusion: Our findings implicate rare homozygous mutations in KIF12 in the pathogenesis of cholestatic liver disease with high GGT in 3 previously undiagnosed children.

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- GGT

gamma‐glutamyltransferase

- KIF12

kinesin family member 12

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- WES

whole‐exome sequencing

Undiagnosed liver disease remains an unmet medical need in pediatric and adult hepatology, including cholestasis of unknown etiology. We1, 2, 3 and others4, 5, 6 have shown the utility of unbiased whole‐exome sequencing (WES) in diagnosing patients with atypical presentations of known liver disorders as well as in identifying novel Mendelian forms of liver diseases. Identification of underlying genetic defects provides new insight into the role of specific genes in the maintenance of normal liver function as well as disease pathogenesis; this finding also identifies potential new therapeutic options for affected patients.

Cholestasis results from impaired bile drainage, leading to stasis and retention of substances in the blood circulation that are normally excreted into bile. For the past 2 decades, application of human genetics and genomics tools to patients with cholestatic liver diseases of unknown etiology has uncovered new genetic causes of cholestasis, resulting in the identification of new disease mechanisms.4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Here, we report 3 children from 2 unrelated consanguineous families with cholestasis and high gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) of unclear etiology, who were found to harbor homozygous damaging mutations in kinesin family member 12 (KIF12). KIF12 belongs to the large kinesin superfamily of microtubule‐associated molecular motors,12 which are known to play critical roles in intracellular transport of organelles and function of the mitotic spindle in cell division.13, 14, 15

Patients and Methods

Human Subjects

This study was performed in accordance with the Dr. Sami Ulus Children’s Hospital and Yale University institutional review board standards. All patients and/or their parents provided written informed consent.

DNA Isolation, Exome Capture, and Sequencing

Genomic DNA of the probands, their unaffected parents, and siblings (when available) was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using standard procedures. WES of genomic DNA from the probands was performed using the xGen capture kit (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Skokie IL) followed by 100 base paired‐end sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq platform (San Diego, CA).

Exome Analysis

WES data were aligned to the reference human genome (build 19), and variants were called using GATK.16, 17 Allele frequencies of identified variants were determined in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), which spans more than 123,000 exomes and approximately 15,500 genomes from unrelated subjects of various ethnicities with or without a diverse array of specific human diseases, including National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Variant Server, 1000 Genomes, and the Exome Aggregation Consortium.18 Variants with minor allele frequency 0.01 or less were annotated using Annovar,19 and the impact of missense variants was predicted using MetaSVM.20

Sanger Sequencing of Genomic DNA

Sanger sequencing of the identified KIF12 mutation (p.Val204Met) was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of genomic DNA of the proband and her parents using forward primer 5′‐CTGCCCTAAACCTGGCATGA‐3′ and reverse primer 5′‐AGCAGAGCCACATCCCTTTC‐3′. Sanger sequencing of the identified KIF12 mutation (p.Arg219*) was performed by PCR amplification of genomic DNA of the proband and his parents and siblings using forward primer 5′‐CCCAACTTTGACCCAGTCCA‐3′ and reverse primer 5′‐GGGAAGGTTGGGTCTTGAGG‐3′. Nomenclature of the KIF12 variants are based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information reference sequence NM_138424.

Orthologs of KIF12

Full‐length orthologs of KIF12 protein sequences from several species were obtained from GenBank, and protein sequences were aligned using the Clustal Omega algorithm.

Results

Clinical, Laboratory, and Liver Histology Features of the 3 Children with Unexplained Cholestasis

Patient 1 is a 22‐month‐old girl offspring of a first‐cousin union who presented with neonatal cholestasis of unclear etiology at approximately 1 month of age (Fig. 1A). She was born full term without immediate complications and had no family history of liver disease in her parents. Physical examination was remarkable for jaundice and hepatomegaly. Laboratory tests were remarkable for elevated GGT, high direct hyperbilirubinemia, elevated transaminases, elevated alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP) level, and hypercholesterolemia (Table 1 and Supporting Fig. S1). Initial abdominal ultrasound showed unremarkable liver parenchyma and grade 1 left hydronephrosis. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a mild increase in left renal pelvic anterior–posterior diameter to 6 mm and no other significant abnormalities. Liver biopsy at 2.5 months of age showed bridging fibrosis with early nodule formation, mixed portal inflammatory infiltrate, multinucleated giant hepatocytes, extensive hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis, ductular reaction, and bile duct loss (Fig. 1B). At 8 months of age, laboratory tests showed slightly elevated serum bile acids and down‐trending GGT, total bilirubin, transaminases, AFP, triglycerides, and total cholesterol (Table 1 and Supporting Fig. S1). AFP level was normalized by 13 months of age. Most recent laboratory tests at 22 months of age showed persistent elevated GGT and elevated transaminases (Supporting Fig. S1).

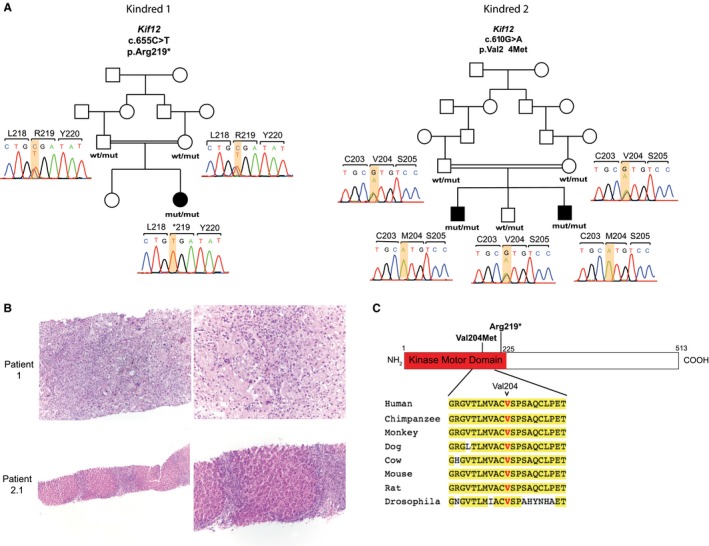

Figure 1.

Cholestasis due to recessive mutations in KIF12 identified in 3 children. (A) Homozygous mutations in KIF12 identified in 3 children with cholestasis of unclear etiology. Pedigrees of 2 consanguineous families (shown with a double line) with cholestasis of unclear etiology are depicted. Affected and unaffected subjects are shown as black‐filled and white‐filled symbols, respectively. Corresponding Sanger sequencing chromatograms of the 3 cases, their parents, and 1 sibling are depicted and denoted as wild type and mutant. Mutations (p.Arg219* in kindred 1 and p.Val204Met in kindred 2) are homozygous in affected subjects and heterozygous in unaffected parents and sibling. (B) In patient 1, lower magnification of liver parenchyma (upper‐left image, 100x) shows early nodule formation, mixed portal inflammation, and mild ductular reaction. Higher magnification (upper‐right image, 200x) shows lobular disarray with thickened cords, numerous multinucleated giant hepatocytes, and extensive hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis. In the center, there is a portal area showing bile duct loss and mixed inflammatory infiltrate. In patient 2.1, lower magnification of liver parenchyma (lower‐left image, 40x) shows biliary pattern of cirrhosis with nodule formation, mixed portal inflammation, and mild ductular reaction. Higher magnification (lower‐right image, 100x) also shows nodules with thickened cords, pseudo‐acini formation, ductular reaction, and bile duct loss. (C) Schematic representation of human KIF12 protein with kinase motor domain depicted in red, where both mutations (shown in bold) are located. Conservation of Val204 position across KIF12 orthologs is shown. Amino acids that are identical to the human protein are highlighted in yellow. Abbreviations: mut, mutant; wt, wild type.

Table 1.

Summary of Demographics and Genetic, Clinical, and Laboratory Findings of the Children With High GGT Cholestasis and Recessive Mutations in KIF12

| Patient Number | Ethnicity (Consanguinity) | Age of Onset | Presenting Clinical Features | Homozygous Mutation | GGT (U/L) | ALP (U/L) | Fasting Serum Bile Acids (NR < 10 μmol/L) | Total/ Direct Bilirubin (NR < 2/< 0.5 mg/dL) | AST/ALT (NR < 47/< 39 U/L) | Current Status/Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Syrian (yes) | 1 month | Cholestasis (high GGT) | p.Arg219* | 998 (NR < 204) | 732 (NR = 60‐321) | 12 | 4.1/3.5 | 147/109 | Alive with native liver/22 months |

| 2.1 | Turkish (yes) | 2 months | Cholestasis (high GGT) | p.Val204Met | 521 (NR < 204) | 703 (NR = 110‐302) | 38.3 | 4.5/3.8 | 105/87 | Alive with native liver/21 months |

| 2.2 | Turkish (yes) | 9 years | Genotype led to recognition of cholestasis | p.Val204Met | 62 (NR < 23) | 422 (NR = 110‐341) | 33.5 | 0.7/0.2 | 84/88 | Alive with native liver/10 years |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; and NR, normal range.

Patient 2.1 is a 21‐month‐old male offspring of a second‐cousin union who also presented with neonatal cholestasis of unclear etiology at 2 months of age (Fig. 1A and Table 1). He has two siblings, and his mother had a spontaneous abortion. He was born full term without immediate complications and had no family history of liver disease in his first‐degree family members. Like patient 1, physical examination was remarkable for jaundice and hepatomegaly, and laboratory tests revealed elevated GGT, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, transaminases, AFP, triglycerides, and total cholesterol (Table 1 and Supporting Fig. S1). At approximately 3 months of age, the patient underwent MRI cholangiogram that showed mild increase in the right renal pelvic anterior–posterior diameter but no biliary dilatation, strictures, or other liver‐related abnormalities. Liver biopsy performed at 3.5 months of age showed biliary pattern of cirrhosis with mixed portal inflammatory infiltrate, mild ductular reaction, pseudo‐acini formation, duct loss, and nodule formation (Fig. 1B). At 4 months of age, serum bile acids were measured and found to be elevated (Table 1). Follow‐up laboratory tests showed resolution of hyperbilirubinemia and normalization of AFP and serum lipid panel by 6 months of age, whereas GGT, alkaline phosphatase, and liver enzymes remained persistently elevated (Supporting Fig. S1). Upper endoscopy at 21 months of age revealed no esophageal varices.

Patient 2.2 is a 9‐year‐old boy and an older sibling of patient 2.1 who was followed for prolonged jaundice of unclear etiology until 2 months of age. Physical examination was unremarkable. Liver function tests were remarkable for elevated GGT, alkaline phosphatase, transaminases, and serum bile acids (Table 1). Recent abdominal ultrasound showed heterogeneous liver and splenomegaly. Follow‐up abdominal MRI showed liver heterogeneity consistent with chronic liver disease with no biliary dilations or strictures and caliectasis of the upper pole of the left kidney. Upper endoscopy showed no esophageal varices or portal hypertensive gastropathy. No liver biopsy was obtained.

Thus far, all 3 patients have shown international normalized ratio and albumin levels within normal limits and no signs of liver decompensation.

Homozygous Damaging Mutations in KIF12 in Probands

We performed WES of germline DNA isolated from peripheral leucocytes of one proband of each family. Targeted bases were sequenced by a mean of 25 independent reads, with 91% of targeted bases having more than eight independent reads (Supporting Table S1).

Because the probands are both the offspring of consanguineous union, we sought rare homozygous variants (minor allele frequency ≤ 0.01 in public databases) that are predicted to result in loss of function of the encoded protein (i.e., nonsense, frameshift, and splice‐site variants) or are predicted to be damaging missense variants by MetaSVM. Consistent with consanguinity, this analysis identified eight and six rare autosomal homozygous genotypes in the probands, respectively. Notably, both probands had a rare homozygous mutation in the kinase motor domain of KIF12 (Fig. 1A,C and Table 2), and there was no other gene with rare variants in both kindreds. Patient 1 is homozygous for a variant encoding a p.Arg219* (chr9:116857353, G>A) premature termination. This variant was extremely rare in public databases, with no homozygotes and a minor allele frequency of 3.233 × 10–5 in the gnomAD database (Table 2).18 Patient 2 is homozygous for a missense variant encoding p.Val204Met (chr9:116857398, C>T), which is a highly conserved position across orthologues and is predicted to be a damaging mutation by MetaSVM (Fig. 1C and Table 2). This variant was also extremely rare, with no homozygotes and an allele frequency of 2.1 × 10–5 in the gnomAD database (Table 2). Sanger sequencing in each case confirmed the homozygous mutation in probands and the heterozygous carrier state of their consanguineous parents (Fig. 1A). In addition, a sibling of patient 2, a 9‐year‐old male, also had cholestasis with elevated GGT (Table 1). He too was homozygous for the p.Val204Met mutation (Fig. 1A). From the pedigree structures, we infer that the probability of finding all affected members of these 2 kindreds to have rare homozygous variants at the same locus by chance to be 1 in 5,012 (logarithm of the odds score 3.7), indicating significant evidence of linkage. Together, these findings provide strong evidence that these mutations are the cause of cholestasis and chronic liver disease in these families.

Table 2.

Rare Homozygous Variants in KIF12 Identified in the Patients

| Patient Number | Chr:Position (hg19) | Nucleotide Change | AA Change | MetaSVM Score (Prediction)* | NHLBI | 1000G | ExAC | gnomAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9:116857353 | G > A | p.Arg219* | Truncating | 0 | 0 | 1.73 × 10−5 | 3.233 × 10−5 |

| 2.1 | 9:116857398 | C > T | p.Val204Met | 0.478 (D) | 0 | 1.9968 × 10−4 | 2.58 × 10−5 | 2.092 × 10−5 |

| 2.2 |

MetaSVM scores missense variants on a scale from ‐2 to 3, with scores greater than 0 predicted to be damaging.

Abbreviations: 1000G, 1000 Genome database; AA, amino acid; Chr, chromosome; D, damaging; ExAC, Exome Aggregation Consortium database; and NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project database.

Discussion

Our findings implicate rare homozygous mutations in KIF12 in the pathogenesis of cholestatic liver disease with high GGT in 3 previously undiagnosed children. First, the genetic evidence is strong, with significant evidence of genetic linkage of rare damaging mutations in KIF12 that segregate with the disease in 2 consanguineous kindreds. Second, the clinical features and liver histologies obtained at early age from patients 1 and 2.1 share very similar liver parenchyma features, such as advanced fibrosis, mixed inflammatory infiltrate, ductular reaction, and bile duct loss. Third, Kif12 modulates biliary phenotype severity, including cholangitis, and cystic kidney disease,21 in a well‐characterized murine model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. In this model, the presence and absence of a biliary phenotype varies based on the genetic background; the presence of a strain‐specific 15 base‐pair insertion within the kinase motor domain of Kif12 21 produces the biliary phenotype. Fourth, the hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 beta, a transcription factor that is important in biliary epithelium formation,22 regulates Kif12 expression in cell‐based and mouse models,23 providing support for a potential role of Kif12 in bile duct epithelial cell function.

Interestingly, all 3 children were found to have mild renal pelvic abnormalities on imaging studies with unremarkable kidney function. Within this small cohort of patients, it is also remarkable that, although 2 of the affected individuals presented with jaundice and marked cholestasis within the first few months of life, patient 2.2 has been overall asymptomatic during his first 10 years of life despite a history of prolonged neonatal jaundice, and it was the knowledge of his genotype that led to recognition of his “silent” underlying cholestatic liver disease.

Of note, recessive mutations in doublecortin domain containing protein 2 encoded by DCDC2, a microtubule‐associated protein, are known to cause neonatal sclerosing cholangitis (which presents with high GGT).5, 6 Other well‐characterized genetic disorders presenting with high GGT cholestasis in children comprise MDR3 deficiency and Alagille syndrome. Although the latter exhibit typical extrahepatic manifestations that are absent in our patients, MDR3 deficiency is a cholangiopathy with variable rate of progression and liver histological features reminiscent of the findings seen in the KIF12 mutant patients described here.

Lastly, during the final stages of preparation of this manuscript, an independent study was published online describing 4 children from 3 unrelated families with high‐GGT cholestasis of unclear etiology, and no extrahepatic abnormalities who were found to harbor recessive mutations in KIF12. 24 Two of the 4 affected children underwent liver transplantation at 6 years and 10 months of age, respectively.24 The latter harbors the aforementioned p.Val204Met missense mutation identified in our patients 2.1 and 2.2. Hence, the full clinical spectrum of this new cholestatic liver disease due to recessive mutations in KIF12 will be determined by the study of additional patients and the longitudinal follow‐up of all described patients. Future functional studies will be key to elucidate the role of KIF12 in biliary function in humans, with the goal of potentially identifying novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of cholestasis.

Collectively, this study highlights the critical importance of using unbiased genomic analysis in the diagnosis of children with liver disease of indeterminate etiology, such as idiopathic cholestasis, which cannot be determined through conventional approaches such as biochemical, imaging, and histological tests.

Supporting information

Acknowledgment

We thank all of the patients and their families for their contribution to advancing our understanding of liver disease, the staff of the Yale Center for Genomic Analysis for the whole‐exome sequencing, and Lynn Boyden for the helpful discussion.

Supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Centers for Mendelian Genomics (U54 HG006504 to R.P.L.); the NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K08DK113109 to S.V.); and the Yale Liver Center (P30DK034989 to S.V.).

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

- 1. Vilarinho S, Choi M, Jain D, Malhotra A, Kulkarni S, Pashankar D, et al. Individual exome analysis in diagnosis and management of paediatric liver failure of indeterminate aetiology. J Hepatol 2014;61:1056‐1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vilarinho S, Sari S, Yilmaz G, Stiegler AL, Boggon TJ, Jain D, et al. Recurrent recessive mutation in deoxyguanosine kinase causes idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Hepatology 2016;63:1977‐1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vilarinho S, Sari S, Mazzacuva F, Bilguvar K, Esendagli‐Yilmaz G, Jain D, et al. ACOX2 deficiency: a disorder of bile acid synthesis with transaminase elevation, liver fibrosis, ataxia, and cognitive impairment. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:11289‐11293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sambrotta M, Strautnieks S, Papouli E, Rushton P, Clark BE, Parry DA, et al. Mutations in TJP2 cause progressive cholestatic liver disease. Nat Genet 2014;46:326‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grammatikopoulos T, Sambrotta M, Strautnieks S, Foskett P, Knisely AS, Wagner B, et al. Mutations in DCDC2 (doublecortin domain containing protein 2) in neonatal sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 2016;65:1179‐1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Girard M, Bizet AA, Lachaux A, Gonzales E, Filhol E, Collardeau‐Frachon S, et al. DCDC2 mutations cause neonatal sclerosing cholangitis. Hum Mutat 2016;37:1025‐1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bull LN, Thompson RJ. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Clin Liver Dis 2018;22:657‐669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strautnieks SS, Bull LN, Knisely AS, Kocoshis SA, Dahl N, Arnell H, et al. A gene encoding a liver‐specific ABC transporter is mutated in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Nat Genet 1998;20:233‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen F, Ananthanarayanan M, Emre S, Neimark E, Bull LN, Knisely AS, et al. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, type 1, is associated with decreased farnesoid X receptor activity. Gastroenterology 2004;126:756‐764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bull LN, van Eijk MJ, Pawlikowska L, DeYoung JA, Juijn JA, Liao M, et al. A gene encoding a P‐type ATPase mutated in two forms of hereditary cholestasis. Nat Genet 1998;18:219‐224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Vree JM, Jacquemin E, Sturm E, Cresteil D, Bosma PJ, Aten J, et al. Mutations in the MDR3 gene cause progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:282‐287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miki H, Setou M, Kaneshiro K, Hirokawa N. All kinesin superfamily protein, KIF, genes in mouse and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:7004‐7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hirokawa N. Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins and the mechanism of organelle transport. Science 1998;279:519‐526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vale RD, Fletterick RJ. The design plan of kinesin motors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1997;13:745‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharp DJ, Rogers GC, Scholey JM. Microtubule motors in mitosis. Nature 2000;407:41‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next‐generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20:1297‐1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy‐Moonshine A, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2013;43:11.10.11‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein‐coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285‐291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high‐throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dong C, Wei P, Jian X, Gibbs R, Boerwinkle E, Wang K, et al. Comparison and integration of deleteriousness prediction methods for nonsynonymous SNVs in whole exome sequencing studies. Hum Mol Genet 2015;24:2125‐2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mrug M, Li R, Cui X, Schoeb TR, Churchill GA, Guay‐Woodford LM. Kinesin family member 12 is a candidate polycystic kidney disease modifier in the cpk mouse. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:905‐916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coffinier C, Gresh L, Fiette L, Tronche F, Schutz G, Babinet C, et al. Bile system morphogenesis defects and liver dysfunction upon targeted deletion of HNF1beta. Development 2002;129:1829‐1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gong Y, Ma Z, Patel V, Fischer E, Hiesberger T, Pontoglio M, et al. HNF‐1beta regulates transcription of the PKD modifier gene Kif12. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:41‐47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maddirevula S, Alhebbi H, Alqahtani A, Algoufi T, Alsaif HS, Ibrahim N, et al. Identification of novel loci for pediatric cholestatic liver disease defined by KIF12, PPM1F, USP53, LSR, and WDR83OS pathogenic variants. Genet Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials